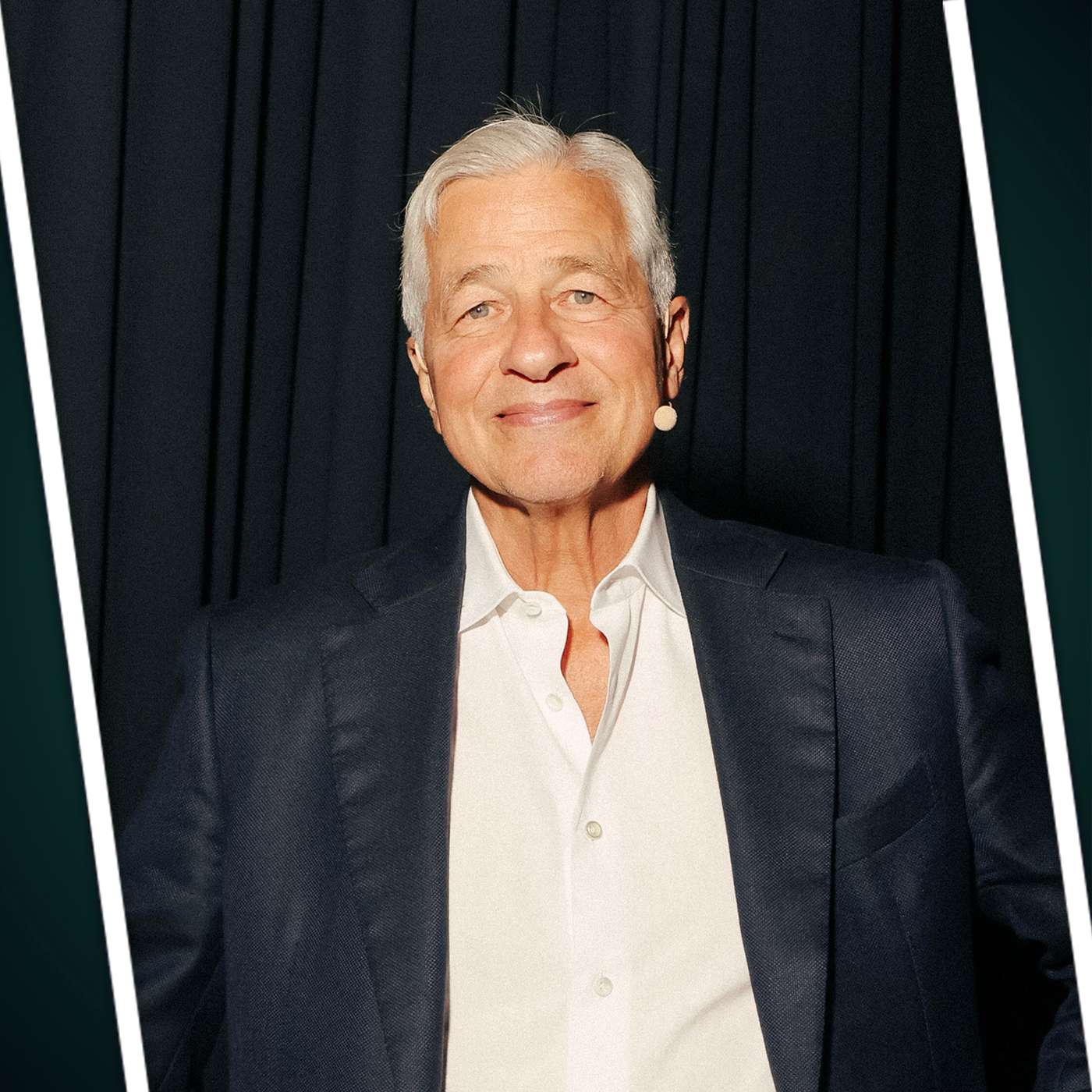

The Jamie Dimon Interview

We sit down with Jamie Dimon for a live conversation at Radio City Music Hall, covering the incredible journey from his 1998 firing at Citgroup (where he was widely expected to become CEO) to building the most powerful bank in the world. Today JPMorgan Chase is a juggernaut — the most systemically important non-governmental financial institution in the world, with over twice the market capitalization of its nearest competitor. But it certainly wasn’t always this way! Jamie takes us from his career restart at the struggling Chicago-based Bank One through how he transformed that platform into the foundation for the modern JPMorgan Chase. We dive into the “fortress balance sheet” strategy that has defined his tenure, and cover blow-by-blow Jamie’s approach to the Great Financial Crisis, Bear Stearns, WaMu, First Republic and more. Tune in for an incredible conversation, live from New York City’s most iconic venue!

Sponsors:

Many thanks to our fantastic Summer ‘25 Season partners:

Episode image photo credit: Rockefeller Center

More Acquired:

- Get email updates with hints on next episode and follow-ups from recent episodes

- Join the Slack

- Subscribe to ACQ2

- Check out the latest swag in the ACQ Merch Store!

Note: Acquired hosts and guests may hold assets discussed in this episode. This podcast is not investment advice, and is intended for informational and entertainment purposes only. You should do your own research and make your own independent decisions when considering any financial transactions.

Press play and read along

Transcript

Speaker 1

David, we completely blew it. We went into Jamie Dimon's office, had our little meet and greet.

We did not ask about the dual pistols.

Speaker 2

Yeah, from the duel, Alexander Hamilton and Aaron Burr, which JP Morgan owns and keeps in their headquarters. And we blew it.

We didn't ask to see them. We'll just have to come back.

Speaker 1 When they finish the new building, I'm sure they will be in the executive floor. We can go get a viewing of the piece of American history.

Speaker 2 All right, Speaking of American history, let's do it.

Speaker 1 Let's do it.

Speaker 1 Is it you? Is it you? Is it you? Who got the truth now now?

Speaker 1 Is it you? Is it you? Is it you? Second down, take it straight.

Speaker 1 Got the truth now.

Speaker 1 We got the truth.

Speaker 1 Welcome to the summer 2025 season of Acquired, the podcast about great companies and the stories and playbooks behind them. I'm Ben Gilbert.

Speaker 2 I'm David Rosenthal.

Speaker 1 And we are your hosts.

Speaker 1 Today's episode is the story of a rising star on Wall Street in the 1980s, who worked with his mentor to merge and acquire their way to the top of the financial world in the 90s, who then got fired unexpectedly by that same mentor who cast about deciding what to do next.

Speaker 1 And then in 2000, accepted a job turning around a poorly run Midwestern bank.

Speaker 1 Then, over the next 25 years, he would orchestrate one of the most remarkable runs in banking history and really all of corporate history.

Speaker 1 This is the story of Jamie Dimon and how he created the modern financial behemoth, J.P. Morgan Chase, out of the beleaguered component parts of Bank One, J.P.

Speaker 1 Morgan Chase, Bear Stearns, Washington Mutual, and First Republic.

Speaker 1 Jamie is now the longest-serving CEO of any major Wall Street bank and is viewed as kind of the great stabilizer of the American financial system, especially during the 2008 financial crisis.

Speaker 1 He now sits atop the largest bank in the U.S. with an over $800 billion market cap, which is more than twice their nearest competitor.

Speaker 1 They are the only bank within spitting distance of the sort of big trillion-dollar tech companies that we've covered here on acquired.

Speaker 1 And to really put a finer point on the dominance, they are the most valuable company east of the Mississippi in the United States and the only company east of the Mississippi worth more than half a trillion dollars.

Speaker 2 Incredible.

Speaker 1 So the question, of course, is how did he do it? I mean, banks fail.

Speaker 1 Financial firms often have spectacular blow-ups and large organizations, period, financial or not, can often get so bloated that they slow down to a crawl. So what did Jamie Dimon do differently?

Speaker 1 Well, today's episode, we have Jamie with us, himself, to tell the story. We recorded this live in front of 6,000 Acquired fans at Radio City Music Hall in New York City.

Speaker 1 So you'll notice it's a different format than our usual episode. We're always trying to figure out what version of Acquired works live with an audience, and this is our latest iteration.

Speaker 1 The Radio City show also had a second act, a late-night talk show, where we had conversations with the CEO of the New York Times, Meredith Kobit-Levian, and the chairman of IAC, Barry Diller, plus some cameos from around the Acquired cinematic universe.

Speaker 1 And we cannot wait to share all of that with you at a later date. Well, if you want to know every time an episode drops, check out our email list, acquired.fm slash email.

Speaker 1 Come join the Slack and talk about this with us afterwards, acquired.fm slash Slack.

Speaker 1 If you want more acquired between each monthly episode, check out ACQ2, our interview show where we talk with founders and CEOs building businesses in areas we've covered on the show.

Speaker 1 And before we dive in, we want to briefly thank our presenting partner, JP Morgan.

Speaker 2 Yes, the same JP Morgan, which is funny because when we started planning this show together, gosh, almost a year ago, it was immediately clear to Ben and me that the very best person who acquired Could Interview in New York also happened to be their CEO.

Speaker 1 And as you all know from the episodes over the last couple of years, JP Morgan has been a fantastic partner of ours and their payments team demoed all kinds of cool technology at the event.

Speaker 1 Our huge thanks to the JP Morgan team for putting on the show with us. And if you ever want to learn more, just click the link in the show notes and tell them that Ben and David sent you.

Speaker 1

So with that, this show is not investment advice. David and I may have investments in the companies we discuss.

And this show is for informational and entertainment purposes only.

Speaker 1 On to our conversation with Jamie Dimon.

Speaker 1 Well, this feels appropriate.

Speaker 2 You guys dressed up for me.

Speaker 2

You dressed up for us too. Thank you.

Last year we had you on the video board at Chase and you were looking very summery there. You look great tonight.

Speaker 2 Yes.

Speaker 1 Well, we know you're a big history buff, and we consider ourselves historians above all else.

Speaker 1 So, what we'd like to do here tonight is walk through the 20-year story with you of sort of how you turned J.P.

Speaker 1 Morgan Chase from a bank among many, a bank among many, to the most systemically important financial institution in the world. Are you game?

Speaker 2 Sound good? Sounds great. Thank you.

Speaker 2 We want to start in 1998.

Speaker 2 You and your mentor, Sandy Weil, have just spent the past 13 years building the modern financial institution conglomerate. Really, the blueprint for what JP Morgan Chase is today.

Speaker 2 Except it's not JP Morgan, it's Citigroup. And everybody on Wall Street and the entire world expects that you are going to be named CEO of Citigroup in short order.

Speaker 1 This is 1998.

Speaker 2

1998. This is not what happens.

Instead, you get fired. And you have to restart your whole career, everything, your whole life from scratch.

Speaker 1 Sorry to start here, by the way.

Speaker 2 Before we get into what you do next, what was the model that you and Sandy built at Citigroup? Okay, first of all, I am thrilled to be here.

Speaker 2 I want to congratulate these guys for building the acquired.

Speaker 2 It's a great, intelligent addition to... what we need to learn in society.

Speaker 2 And so I would say it wasn't quite the model because if you look at what we did at Commercial Credit Primeric was then travelers and merged. We were a financial conglomerate.

Speaker 2

We bought lots of companies and lots of different businesses. We fixed them up.

We turned around, we made money, and then we merged it with Citibank, which obviously was a huge bank.

Speaker 2 And my view is: we should skinny it down and kind of shed the parts that aren't that important to the rest of the company and keep the things that strategically belong together together.

Speaker 2 It was one of my small disagreements with Sandy about the future of the company.

Speaker 2 But it was big, it was making a lot of money, it was quite successful at the time, and then I got fired.

Speaker 1 So, how are you feeling in that moment?

Speaker 2 When I got fired? Yeah, that moment. Well, you know, my wife is here, and I was hosting 100 people,

Speaker 2

recruiting kids in my apartment in New York City, same apartment I have now. And they called me, we haven't imagined me to Sunday at 4 p.m.

that night.

Speaker 2 And Sandy and John Reed called me up and said, can you come a little early? We've got a bunch of stuff to talk about. I was the president, chief operating officer.

Speaker 2 I said, I can't. They said, well, well it's really important so I drove up there

Speaker 2 and I sat down in the room with Sandy and John and they said they want to make a few changes and there are three of them and they said we one one we want to make this person in charge of that I said okay well that didn't make sense to me the second one they wanted to make someone in charge of the Global Investment Bank which I was running I thought it was another stupid decision and the third is they said and we want you to resign and I said okay

Speaker 2 because you know at that moment I knew it was all arranged the boards boards had voted, the press release was written, the management team was coming up. So I waited

Speaker 2

for the management team to come up. I wished them the best.

I said, you guys have a chance to build one of the great companies. They all thanked me.

Speaker 2

Sandy said, you want to do the press with me? I said, yeah, but I'll do it from home. So I went home, went to see my kids.

They were like, one of my daughters here too.

Speaker 2

They were like 12, 14, 12, and 10. And I walk in the front door and I tell them, you know, I was fired.

And the youngest one says, Daddy,

Speaker 2 do we have to sleep on the streets? I said, no, no, we're okay. And the middle one, who's always obsessed with college for some reason, can I still go to college? He said, yeah.

Speaker 2 And the one who was here was the oldest one said, great.

Speaker 2 Since you don't need it, can I have your cell phone?

Speaker 2 And then that night, about 50 people came over. All the same people I just met, all the management team, bringing whiskey, and it was like, have been in your own wake.

Speaker 2 And there's one really tall guy who came in, a very good friend of mine. And he looks, and my daughter looks up and says, who are you? He says, I work for your daddy.

Speaker 2 And she says, not anymore, you don't.

Speaker 2

And that was it. I was okay.

You know, I was like, I tell people, it was my net worth, not my self-worth, that was involved.

Speaker 1 And for anyone who doesn't sort of already know Jamie's story, you were the rising star. I mean, you were, the city was the biggest bank.

Speaker 1

You were the heir apparent. I mean, this was like unfathomable.

And for you to take it this gracefully,

Speaker 1 you know, it says a lot.

Speaker 1 So

Speaker 1 you're sort of wandering in the woods as I, best I can kind of reconstruct it for about 18 months. Is that right? Figuring out what's next?

Speaker 2

Yeah. I, you know, it took me a while to exit and sign agreements and get out.

They were kind of mean.

Speaker 2 But and then I stepped into office and it was late. We went for a nice long vacation and stuff like that.

Speaker 2 When I got back in September, so that was six months later, I went to my, I started going to work here.

Speaker 2 I had nothing to do, but I went from, you know, to nine to five and started calling people and thinking about what I'm going to do.

Speaker 2 it was in the segments building so i can go for lunch uh downstairs every day and i did four seasons at the four seasons and i explored everything started my own merchant bank i could have retired just teaching uh just investing but i was 42.

Speaker 2 and you you took a call about running amazon right say it again you took a call about running amazon didn't you i went to i loved i went to visit jeff bezos who was looking for a president at the time he and i hit it off we've been friends ever since he's an exceptional human being but it was like a bridge too far even though that movie just came out when Sally met Harry, I was thinking, my God, I'll never wear a suit again.

Speaker 2 I'm going to live in a houseboat. This would be really great.

Speaker 2

What an alternate universe we'd be living in. It would have been an alternate universe.

But I'm still good friends with Jeff, so I got at least one good thing out of it. And then I got serious.

Speaker 2 And I was offered jobs to run

Speaker 2 other big global investment banks.

Speaker 2

Hank Greenberg, who ran AIG, called me up and said, you should come join us. I was thinking, I'm going to go from Sandy Wilde to you.

I mean, I have to have my head examined to do something like that.

Speaker 2

Imagine you know the AIG story. Then, yeah, well, that happened years later, too.

And then I got a phone call from Headhunter about Bank One.

Speaker 2 And I was also, you guys, a lot of you probably know Ken Langone and Bernie Marcus and Arthur Blank. We ran Home Depot.

Speaker 2

I loved them. But at my first dinner with them, I went to see them in Atlanta.

I said, I have to make a confession. Until you guys called, I had never been in a Home Depot.

Speaker 1 We were actually wondering, David and I were debating.

Speaker 2 We were talking about that. My friend,

Speaker 2 my friend made me go up there and get some equipment and plants and stuff like that.

Speaker 2

But I love their culture, their attitude. They wanted me to do it.

Ken Leon Gohan says, I still should have gotten you. I wasn't going to pay you enough.

Speaker 2 Of course, it had nothing to do with anything like that.

Speaker 2 And I had Bank One. But Bank One

Speaker 2

was my habitat. I was used to financial companies, services, banking.

It wasn't quite global. It was a little global at the time.

Speaker 2

And, you know, it was a troubled bank. And I decided that life is what you make it.

It was hard hard in my family.

Speaker 2

We had to move. I think for anyone who's going to move, kids that, I think they were 14, 12, 10 or something like that.

It's hard. Some context on Bank One for folks who are not familiar.

Speaker 2 It's not in New York. It's a large bank, but it's a troubled bank.

Speaker 1

It's based in Chicago. It's large, David.

It's a $30 billion market cap bank. Citigroup, where you just had been before, was a $200

Speaker 2 billion bank. It was $21 billion at the time.

Speaker 2 You have the right numbers, but it did a split.

Speaker 2 And so if you look back, it was more like 20 billion or something like that yeah and Citi was 200 but you know I didn't worry about that I was like you know in life you make things what they are I don't like complaining about over spilled milk you know you just put on your pants you get going you see what you can make out of it and uh but you it sounds like you had opportunities to stay in New York to run I did bigger more glamour this one I was going to run the company The other ones would have been some investment banks.

Speaker 2 I didn't really trust some of the people who were talking to me about that. And there's a whole bunch of other stuff that I explored.

Speaker 2 I took phone calls, some small companies, some big companies a couple of subprime mortgage companies who called me and I was like absolutely not

Speaker 2 we'll get to that we'll get to that we'll get to that and so I just thought this was a chance you know and you know if the family is willing to move and we got a nice took us a while we had lived in a rental for a while but got a nice brownstone and you know we love end up loving Chicago Chicago is a wonderful city in a lot of different ways and and you know like I said it is what you make it you know and I what I put half my money in the stock at the time yeah you

Speaker 2 I was going to be the captain of the ship. I was going to go down with the ship.

Speaker 2 I made it clear to everyone I was here permanently, and it'll be what it is. And so I got to work literally the next day.

Speaker 1 Did we do the math right that right before you joined Bank One, you bought $60 million of stock? I did.

Speaker 1 I mean,

Speaker 1 I've never heard of someone taking a CEO job and saying, I'm going to invest half my net worth in this company now. Yeah.

Speaker 2 And

Speaker 2 I thought it might be overvalued a little bit because

Speaker 2 people thought it might be sold or something like that. But I didn't care about that.

Speaker 2 You know, if you work at a company and the new CEO comes in, he's from out of town, and you're going to have a lot of shareholders. And

Speaker 2

I knew a lot of the shareholders. I was going to know a lot of the shareholders.

I wanted to know I was in 100%.

Speaker 2

Lock, stock, and barrel. There was no question.

I would never sell that stock. And I'm going to go down with the ship or go up with the ship.

Speaker 2 And they also, you, I was making decisions that I thought were right for the long-term health of the company.

Speaker 2 Not for a short-term type of thing.

Speaker 1 So, what did you find when you got there? Day one on the job, you start investigating. Is it better versed the same than you thought?

Speaker 2

You know, there had been an analyst called Mike Mayo who had done a report. I remember one of the great lines of the report.

Even Hercules couldn't fix it.

Speaker 2 It had been an amalgamation of Bank One, First Chicago, National Bank of Detroit. They had never put the companies together.

Speaker 2 So, they had multiple statement systems, processing systems, payment systems, you know, SAP systems.

Speaker 2

They had different brands. You know, services coming down.

We were losing accounts. They were closing branches.

It was a mess. But you know, it was all of it, systems, people, ops.

Speaker 2

But again, I just, you know, I just, I met the management team. It's hard.

You know, I walked in, I met six of the directors.

Speaker 2 There were 21 directors. 11 hated the other 10.

Speaker 2

Wait, wait, wait. There were 21 board members.

21 board members from the merged multiple acquisitions.

Speaker 2

They were tribal. They ended up hating each other.

I knew that when I went in because I knew people, and I spoke to a lot of people and did research in the bank.

Speaker 2 But again, in life, you get handed these things, and it's not perfect.

Speaker 2

Even today, people want to be handed something perfect. It's not perfect.

And I was, so I met six directors. I walked in when I got off of the job.

I shook all their hands.

Speaker 2

I told them I'm going to do the best I do. I'm going to tell you the truth, the whole truth, the truth, the good, the bad, the ugly.

We're not going to bullshit.

Speaker 2 We're going to try to build a great company. I'm going to need your help.

Speaker 2 And

Speaker 2 then they said

Speaker 2 they left.

Speaker 2 So now I'm on the executive floor. I don't even know where to go.

Speaker 2

And so I kind of knocked on someone's door, the head of HR. I said, I do need an office and I really need an assistant.

And they were going to give me the chairman's office in the corner.

Speaker 2 I said, no, no, I want to be like right in the middle so I can see people and I stick my head out.

Speaker 2 And then I went to meet the management team. I went to this, they put them all in this conference room, nice white plush carpets.

Speaker 2 I walked in with a cup of coffee and they said, Jamie, we don't drink coffee here for obvious obvious reasons.

Speaker 2 So I looked at them, I looked at the coffee, I looked at them, I said, You do now.

Speaker 2

And then I just started meeting with them all, and the systems are terrible. The company was losing money.

I didn't know all the businesses really well, so the credit card company had collapsed.

Speaker 2 That's probably the business I knew the least.

Speaker 2

But again, that didn't matter to me. I was going to try to fix it.

It had some good assets and things like that. So I rolled up my sleeves and went to work.

Speaker 2 One of,

Speaker 2 as when we were chatting a couple of weeks ago and preparing for this,

Speaker 2 we asked you in the context of JPMorgan, like, what are the critical things in your mind that has made JPMorgan what it is today? And the first thing you said was risk.

Speaker 2 And was risk and the culture around risk.

Speaker 1

And the fundamental risk. Understanding by management of risk.

Yeah.

Speaker 2 When you got to Bank One,

Speaker 2 I think this is where you first started putting into practice the culture around risk. What was the risk culture at Bank One and how did you change it? Yeah,

Speaker 2

I've always been very risk conscious. And risk conscious does not mean getting rid of risk.

It means properly pricing it and understanding the potential outcomes.

Speaker 2

And so when I got there, I just started meeting people and going through. I quickly realized that Bank One had more U.S.

corporate credit risk than Citibank did.

Speaker 2

And the way they accounted for it was unbelievably aggressive. And, you know, so they had less capital, less reserves, less this.

They were calling these things profitable.

Speaker 2 They were basically losing money.

Speaker 2 And loans,

Speaker 2

a lot of business, you have to be very careful about the credit business. And once I found out that, I kind of panicked a little bit.

And I went through every single loan in the books.

Speaker 2 I marked them all down, put up more reserves, told the board about it, and then wanted to earn more revenues per dollar of risk.

Speaker 2 So for example, in the middle market business, we had for every loan NII, we had like 80 cents and 20 cents.

Speaker 2

Net interest income for the net interest income from the loan and 20 cents of other revenue like payments. By the time we merged with J.P.

Morgan, we had 40 NI for the loan and 60%

Speaker 2 NIR from other type of things like payments. And one, you're being paid for the risk and one you're being paid little for the risk.

Speaker 2 And I always stress tested and I showed the board that if we have a recession and we're about to have one,

Speaker 2 how much money we'd lose in credit. So I hired a woman called Linda Bamman who said, okay,

Speaker 2

if you're going to let me do credit, you're going to let me sell loans. I said, yes.

Are you going to let me hedge loans? Yes. Can I do 10 billion? I said yes.

Speaker 2 She said, okay, I'll join. And we probably reduced the balance sheet by 50 billion because, and then we did have a recession, but we were kind of okay by then.

Speaker 2 With one big bad one, which is United, which went bankrupt. And we basically owned it for a small period of time.

Speaker 1 There seems to be kind of a fundamental

Speaker 1

Jamie Diamondism, which is don't blow up. I mean, a lot of other people have gotten decent at pricing risk.

But everyone else seems to be willing to get closer to the line than you.

Speaker 1 Where did you sort of develop this don't blow up at all costs conversation?

Speaker 2

So there's, you know, around risk, there's always this ecosystem. You've always heard it.

Everyone's doing it. Everyone's okay.

This is going to work. This time is different.

Speaker 2

And, you know, the history tells you, learned, teaches you a lot. And I always say, if you did, my dad was a stockbroker.

And so I bought my first stock when I was 14.

Speaker 2

In 1972, the stock market hit 1,000. It had hit 1,000 in 1968.

I was already helping a little bit with stuff.

Speaker 2 By 1974, 1974, it was down 45%.

Speaker 2 All the limousines in Wall Street were gone. Restaurants were being closed.

Speaker 2

Markets moved violently. And then we had kind of a recovery.

In 1980, you had a recession. In 82, you had a recession.

In 82, it was lower than it had been in 1968. And it hit 800.

Speaker 2 And then in 87, the market was down 25% in one day. In 1990, all these banks, JPMorgan, Citi, Chase, Chemical, were all taken to their knees by real estate losses.

Speaker 2 and they were all worth about a billion dollars.

Speaker 2 I think Citi was $3 billion at the time, and the other ones were about a billion dollars. And then you had the 97,

Speaker 2

also real estate-related thing. You had the 2000 internet bubble, you know, and then you had the great financial crisis.

And if you go through history, there's tons of these things.

Speaker 2

Andrew Ror Sorkin is in here, and I just read his book. He's nice enough to send it to me, in 1929.

And man, history does rhyme. Too much leverage, too much risk.

Speaker 2

Everyone thinks it's going to be great. No one thinks it can go down a lot.

You know, in that stock market went down 20% one year, 30% next year, 20% next year. At one point, it was down 90%.

Speaker 2 Shit happens.

Speaker 1 It seems like your philosophy is that

Speaker 2 the worst thing will happen.

Speaker 1

So just plan for it. Don't say, oh, we're good as long as this crazy, insane, you know, Four Sigma event doesn't happen.

You're like, no, that will happen and happens often.

Speaker 2 Yeah, so

Speaker 2 when I look at it, I always ask, like, when I do stress testing at risk for high yield, the worst, I remember getting to J.P.

Speaker 2 Morgan and going through the risk books, and their stress test was that high yield would move 40%, the credit spread.

Speaker 2 And at that time, it was at 400 or whatever it was. That means 560.

Speaker 2 Okay? And I said, no, our stress test is going to be worst ever. Worst ever was 17%.

Speaker 2

And they said, that'll never happen again. The market's more sophisticated.

Well, in 08, it hit 20%, and you couldn't have sold a bond. There was no market.

So, you know, those things do happen.

Speaker 2 And the point isn't that you're trying to guess them. The point is

Speaker 2 you can handle them so you can continue to build your business. And so I always look at what I call the fat tails and manage that we can handle all the fat tails.

Speaker 2

And not the stress test the Fed gives us, but all the fat tails. Markets down 50%, interest rates up to 8%, credit spreads back to worst ever.

Of course, your results will be worse, but you're there.

Speaker 2 And the thing about financial services, leverage kills you. Aggressive accounting can kill you, which a lot of companies do do.

Speaker 2 And the goal should be, and also confidence, if you lose money as a financial company, I always knew this too.

Speaker 2

The headlines are, people read that, and if they're relying on putting their money with you, they look at that different. So I lose trust.

They lose trust.

Speaker 2 And that's what's caused you've seen runs on banks, and you saw some recently

Speaker 2 because people

Speaker 2 take the money out.

Speaker 1 There's a thing that you just said, which is

Speaker 1 that you might do worse, but you're there. There's sort of this this trade-off that you make where you're less profitable in the short term, but at least you stick around.

Speaker 1 If you look back at the companies that you've run, Beguan, JP Borg, and Chase, is that true in the good years that you've actually been less profitable than those who are kind of risk-on?

Speaker 1 Yeah, a little bit.

Speaker 2

And he's saying that, you know, if you look at the history of banks from up until 2007, a lot of banks were only 30% equity. Most of them went bankrupt.

We never did that much.

Speaker 2 Okay, but in 08 and 2009, we were fine and they they weren't.

Speaker 2 But you want to build a real strong company with real margins, real clients, conservative accounting, where you're not relying on leverage. And it's very easy to use leverage to

Speaker 2 jack up returns in any business.

Speaker 2 But in banking, it could be particularly dangerous. So it seems like a core

Speaker 2 part, if not the entirety, of this distilled into your operating strategy is the Fortress balance sheet.

Speaker 2

When did you first hear about the Fortress balance sheet? I've been talking about it. I go way back to Primerica.

I used to talk about that. You're going to be able to survive the tough times.

1990s.

Speaker 2

Probably the 1990s. And like I said, I grew up with my father and I went through those market things.

I remember how hard it was on people in Wall Street.

Speaker 2

But the Fortress balance sheet is that you run a company serving clients well. You have good margins, good liquidity, good capital.

I'm as conservative an accountant as you can find.

Speaker 2

I don't upfront profits, but I can spread them over time. And accounting, of course, accountants hate it when I say this.

You can drive a truck through accounting rules.

Speaker 2 And accounting itself, you know, that certain things are considered expenses, but they're good. They're an investment for the future, but they're called an expense.

Speaker 2

And then revenues, you know, if I make bad loans, they are bad revenues. They will kill you.

But for a while, they look pretty good.

Speaker 2 So it's all those things, margins, clients, and the banking business, the character, the clients you have will reflect on your bank.

Speaker 2 So the first thing is who you're doing business with, how you're doing business, and

Speaker 2 also making sure your compensation plans aren't paying people for stuff which is stupid or unethical. And

Speaker 2 you always have to review these things to make sure you have them right because they change all the time.

Speaker 1 All right, listeners, now is a great time to thank one of our favorite companies, Vercell.

Speaker 2

Yes, Vercel is an awesome company. Over the past few years, they've become the infrastructure backbone that powers modern web development.

And now the AI wave.

Speaker 2 If you visited a fast, responsive, modern website lately or or used a slick AI native app with agents and hyper-personalized interfaces, there's a good chance it was built and deployed on Vercell.

Speaker 1 So for the past decade, they've been on a mission to democratize the lessons of the giants, companies like Google and Amazon and Meta.

Speaker 1 And the idea is developers shouldn't have to spend weeks and engineering resources to stitch together dozens of services just to launch a web app.

Speaker 2

Vercell made it simple. You write code, you ship it.

Fast, globally distributed, and without developing a second skill set in the nuances of deployment.

Speaker 2 That's the magic of their framework-defined infrastructure, which basically lets developers and large teams go from idea to production without any friction.

Speaker 1 So, as you may know, Vercel has been synonymous with front-end development, but now they do back-end and agentic workloads as well.

Speaker 1 Vercel calls this the AI Cloud, purpose-built for the next era of apps and already in production across companies like Under Armour, PayPal, Notion, and AI startups like Runway, Decagon, and Browserbase.

Speaker 2 Yep, the AI cloud takes removing deployment friction even one more step. In some cases, developers don't even need to push code anymore.

Speaker 2 Agents can release features continuously, infrastructure configures itself, and interfaces adapt to how you work.

Speaker 1 If you want to build the future of software, head to vercelle.com/slash acquired. That's ve-r-ce-e-l.com/slash acquired, and just tell them that Ben and David sent you.

Speaker 1 Now is also a great time to thank another of our favorite companies, Anthropic, and their AI assistant, Claude.

Speaker 2 Claude has really transformed our workflow here at Acquired. Preparing to interview Jamie Dimon requires serious research, obviously.

Speaker 2 Decades of banking history, regulatory changes, three financial crises, building the Fortress balance sheet. This is exactly the kind of complex analysis that Claude is excellent at.

Speaker 2 Ben and I have never had assistants here because we think it's important for us to do the research ourselves. But Claude now gives us the best of both worlds.

Speaker 2 It's an extra set of hands that we have full control and visibility into what it's doing and how.

Speaker 1 So where Claude is especially great for me is extended thinking mode.

Speaker 1 When I asked it to analyze JPMorgan's strategy through multiple financial crises, I could watch Claude's reasoning through each decision point step by step.

Speaker 2 And it has full context by connecting to our entire 10-year base of knowledge here it acquired through something called MCP, which you might have heard about, the Model Context Protocol.

Speaker 2 They have pre-built integrations with Gmail and Google Docs, and also services like Jira, Asana, Linear, Square, PayPal, as well as custom integrations for any internal tool that you have.

Speaker 1 And Claude is built by Anthropic with a laser focus on accuracy and trustworthiness, which is exactly what we need.

Speaker 2 Yep.

Speaker 2 If you want to start using Claude yourself or for your organization, go to claude.ai slash acquired, and they've got a special offer for acquired listeners, half-price Claude Pro for three months, which gets you access to all the features mentioned above.

Speaker 1 So whether you're preparing for your own high-stakes meetings, interviews, or conversations, or you just need an AI AI you can trust with serious work, Claude thinks with you, not for you.

Speaker 1 That's claude.ai/slash acquired.

Speaker 1 All right, David,

Speaker 1 catch us up to the merger.

Speaker 2 So you run Bank One for four years from Chicago, and then in 2004, you merge with JPMorgan Chase.

Speaker 2 In what is termed at the time a merger of equals, I think JPMorgan Chase referred to it as that Bank One shareholders get 42%

Speaker 2

of the combined company. I mean, I think people don't realize how much of JPMorgan Chase is Bank One today.

That's why it's a little irritating me when they say you've been running this.

Speaker 2 I was running JP Morgan. I was running 40% of the company for the whole time.

Speaker 2 And

Speaker 2 when I got to Bank One, and I'm not working around the clock, I already knew that a logical, strategic merger might be JPMorgan.

Speaker 2 I know all these companies, and that's the other thing about Fortress balance sheet is you also have real strategies that survive the test of time.

Speaker 2 You're not flipping and flopping.

Speaker 2 And then I'm sitting there, and of course, the tape comes: JP Morgan and Chase to merge. So we're worth like 25 billion, they're now worth like 80 billion or 90 or whatever the number was.

Speaker 2

I'm like, well, there goes that dream. But four years later, our stock was up to doubled or something like that.

There's actually come in, and it was in the target range.

Speaker 2

And I had been meeting with Bill Harrison, the current chairman of JP Morgan at the time. We were talking about it.

We both knew it made business sense. They were kind of looking for a CEO.

Speaker 2 So we had been talking probably for a year and a half before that.

Speaker 1 They're looking for a CEO.

Speaker 1 Did they give Bank One shareholders 42% because they were looking for a CEO?

Speaker 2 There were two lawsuits.

Speaker 2

So we got the premium. They got the name and the location.

And

Speaker 2 I effectively had kind of control from day one because inside the merge agreement, and this is almost unheard of, when we get the premium, is that to not have me become CEO 18 months later, 75% of the board would have to vote me out.

Speaker 2

Your default was you were going to become COE. And the board was eight Bank One people and eight JPMorgan people.

And I knew a lot of the JPMorgan board members, too, who respected me.

Speaker 2

And Bill Harris and I were very close, but that was the agreement. They got sued for paying too much to buy me.

I got sued for not taking enough.

Speaker 2

You get sued. You can't win anything.

I think every shareholder is probably.

Speaker 2

But it worked out. Yeah.

All right, 2006.

Speaker 2 Before we get to 2006,

Speaker 2 when you were going through that process, and even maybe the couple years before you and Bill were talking, you're starting to think about J.P. Morgan as a partner.

Speaker 2 I'm curious, did the brand, did the name JPMorgan factor into your thinking at all? Did you view that as an asset? I mean, JPMorgan brand is a Tiffany name. I didn't value it in the deal.

Speaker 2 And what I looked at, I had given my board,

Speaker 2

I think the first thing is run your company well. And people thought I was going to start doing deals immediately.

I was like, no, we suck.

Speaker 2 We haven't earned the right to run someone else's company yet. When we're running a good company, we can merge with somebody.

Speaker 2

But the first thing I looked at was business logic. And that every business, we had a consumer business, they had a consumer business, we had a credit card business.

They were both terrible.

Speaker 2

They had a credit card business. They had a big investment bank.

We had a big U.S. corporate bank that needed some of those investment banking services.

We both had a wealth management business.

Speaker 2

I knew we could save a lot of cost saves. So the business logic was pretty impeccable.

Then there's the ability to execute. Like, can you actually get it done?

Speaker 2

Because you've all seen a lot of deals where they fall apart. They don't have management.

They don't consolidate the systems. They have infighting.

It kind of happened at Citi.

Speaker 2

And so you don't effectuate. And then there's the price.

So I knew we had a Tiffany brand.

Speaker 2 But it didn't value because if everything else didn't work out, I don't think it would have mattered that much.

Speaker 2

Interesting. All right.

So

Speaker 1

I'm going to fast forward us a couple of years. It's 2006.

You're officially chairman and CEO of the combined JPMorgan Chase.

Speaker 2

And 2006 on Wall Street is like... Go, go, go.

Go, go, go, baby. It's like, you know, 1980s all over again.

Speaker 1 I think you had the same incentives as everyone else, but you behaved very differently. Am I missing something? Did you have the same incentives?

Speaker 2

You pulled JP Morgan back hard on the risk side in 2006. I did.

So there were cracks out there in 2006. You may remember the quants.

There started to be a quant problem.

Speaker 2 And late in 2006, we definitely saw subprime getting bad. And that's, I pulled back on subprime.

Speaker 2 I wish I had done more, because if you look at what I did, you say, okay, well, you saved half the money, but you would have saved more.

Speaker 2 You still had some losses.

Speaker 2 But we also had,

Speaker 2 I'm going to say, less, maybe a third of the leverage of the big investment banks.

Speaker 2

and a lot more liquidity. So in 2006, I started to stockpile liquidity.

And, you know, looking at the situation, I was quite worried.

Speaker 2 The leverage, if you may not remember this, but the leverage, because of accounting rules in Basel III, Basel I, investment banks, particularly the banks, the big investment banks, went from 12 times leverage to 35 times leverage.

Speaker 2 And it was go-go. So for every one of these

Speaker 2 billion, bridge loans, the whole thing.

Speaker 2 In 07, the bridge book of Wall Street was $450 billion.

Speaker 2

Today it's $40 billion. JP1 JP1 can handle the whole $40 billion today, though not the $40 billion today.

And they were much more leveraged deals. And a lot of them fell apart, collapsed.

Speaker 2 And then of course, and that was before you had the collapse in the mortgage markets, which really took down a lot of these banks.

Speaker 1 But you did have the same incentives, and you had the same access to information that a lot of these other folks did, but you didn't blow up.

Speaker 1 What explains this? Because usually behavior follows incentives.

Speaker 2 Yeah, well, first of all, if you work for me, I would tell you, I don't care what the incentive is, don't do the wrong thing.

Speaker 2 And don't do the wrong thing to the client. If you treat yourself, if you're the client, how would you want to be treated? And I had gotten rid of, I mentioned that one risk thing.

Speaker 2

There were multiple risk things like that. They were being paid to take the risk.

So

Speaker 2 you were telling us about the auto loan business. Yeah, but they'd be being paid.

Speaker 2 But the second I put in all these new risk controls, all of a sudden you weren't making money by taking that leverage because I was looking at how much capital can actually be deployed if things get bad.

Speaker 2 And so I was looking at earnings through the cycle. And then, but very importantly, all of these investment banks were doing side deals, private deals, three-year deals, five-year deals.

Speaker 2 I got rid of almost all of them. This is for company bankers.

Speaker 2 So today at JPMorgan Chase, there are no, you know, we do do things, but, and I know some of my partners in the room here, but we all know about it.

Speaker 2 There are no winks, there are no nods, there are no side deals, there's almost no one paid on a particular thing because if you're paid on a particular thing, you can do the wrong thing.

Speaker 2

And meanwhile, you're not helping the company manage its risk or something like that. So we change the incentive programs.

And I'm quite conscious about incentive programs that they don't create

Speaker 2

misbehavior. But it's also very important.

If you're in a company and you say the incentive program is doing that, you should tell the company.

Speaker 2 This incentive plan is not incenting the right behavior versus v the customer. And a lot of it was leverage.

Speaker 2 So if you look at the leverage in some of these securitization books and mortgage books, if you have 30 times leverage and you're you're getting 20% of the profits, you'll go to 40 times leverage.

Speaker 2

It's just going to, it's literally at 25% to your bonus. And so I got rid of the profit pool of 20% and the leverage.

So yeah. And I lost some people too in the meantime.

It's funny.

Speaker 2 Yeah, you know, JP Morgan, as part of the system, had the same incentives, but you changed the incentives for

Speaker 2 the team within the company. Okay.

Speaker 2 All right, we got to go to 2008.

Speaker 2

March. March 13th.

2008. Thursday, 2008.

Speaker 2

It's Thursday night. You get a call from Bear Stern's CEO.

The stock closed that day at $57 a share. It was like $150 a couple months before.

Three days later,

Speaker 2

God, I remember it like yesterday. I was working on Park Avenue in Wall Street.

I remember that night, $2 a share. You're buying Bear Sterns.

Speaker 2

Tell us the story. So I was at Avra on 47th Street with my parents in my parents' favorite restaurant.

My whole family was there. It happened to be my birthday.

Speaker 2 I don't normally get emergency. Happy birthday.

Speaker 2 And Alan Schwartz, who was the current CEO, we'd seen their stock go down. I knew they had some real problems because we saw the hedge funds and some of the things that were taking place there.

Speaker 2 And he said, Jamie, I need $30 billion tonight before Asia opens.

Speaker 2 I said, I don't know how to get $30 billion for you.

Speaker 2 And have you called Paulson? You called Tim Geithner?

Speaker 2

So we all called. I called up the management team.

I went back in. I probably had a bite and said goodbye.

I went back to the office.

Speaker 2 probably had a hundred people come in that day that night they all got dressed they went back to work it's emergency we now rang all the bells for emergency bear stearns went bankrupt spoke to the Fed about let's just get them to the weekend we had one day and we needed a Saturday and Sunday and we concocted this loan so we couldn't lend the 30 billion and the Fed technically couldn't lend the 30 billion but the Fed can lend to us technically and I can technically use the collateral of Bear Stearns so that so we got the literally a one-day loan And then the next day we had thousands of people come in due diligence.

Speaker 2 And we went through every loan, every asset, every balance sheet, all the derivatives, all the lawsuits, all the HR policies, like real due diligence, a two or three day period, and bought the company at that night $2 a share.

Speaker 2 Hank Paulson was telling me, why are you paying anything for it? I said, well, I do have to get shareholder votes.

Speaker 2

Because you need bear shareholders to approach it. It was a public deal.

And the worst part of it is I was going to get the lawsuits from the bear holders. And I knew that.

Speaker 1 But you didn't pay enough.

Speaker 2

But you couldn't let it go bankrupt. There wasn't like an industrial car you can buy in bankruptcy.

It would have been gone. And the crisis would have just unfolded.

So,

Speaker 2 okay, two questions.

Speaker 2 One,

Speaker 2 what would have happened if

Speaker 2 it went down?

Speaker 2 Two, afterwards, did you think it was over?

Speaker 2 No.

Speaker 2 So we already had, so that was March.

Speaker 2

What happened with Lehman was an uncontrolled failure. There was money locked up everywhere.

People panicked. They started pulling money out of everything.

That would have happened with Bayer.

Speaker 2 So it did stop that. And I would have thought that it gave other people other time to clean up their act.

Speaker 2 So, literally, six months later, I would have thought some of these other firms were much had more liquidity, more capital, and were a little bit more prepared for what might be happening.

Speaker 2 We already had the stress in the system.

Speaker 2

You saw it already. It was going to mount.

It wasn't going to go away. There were tremendous losses coming.

Speaker 2 So we bought it, and it probably did help. In hindsight, it didn't stop, you know, didn't stop the crisis from unfolding.

Speaker 2 We bought it and then like a couple like a week later we changed the ten dollars a share. It had been at 120.

Speaker 2 And the way to think of it is it was 300 billion of assets and at a 12 billion dollar book tangible book value. We wrote off the whole tangible book value in the per when we bought the company to pay.

Speaker 2 We had to liquidate the loans, we had a hedge stuff, we had severance costs, lawsuit costs, and we basically used all that.

Speaker 2 So we paid a billion dollars for a a company that had been worth $20 billion recently. The building we're in now was worth a billion dollars on the balance sheet for zero.

Speaker 2 And we got the fact we got some very good people and we got some good businesses, but it was an extremely painful process.

Speaker 1 I've seen estimates that in the fullness of time after

Speaker 1 really dealing with unwinding all the stuff there, it costs you $15 to $20 billion.

Speaker 2 So it costs $20 anyway.

Speaker 2

It was the $12 billion we wrote off. That didn't cost us.

We didn't really pay for it. And then the government sued us on the mortgages, which I was quite offended by.

Speaker 2

And I really was. I thought it was a fighter.

I think it was a problem. Well, this is the government.

When you,

Speaker 2 you know,

Speaker 2 whatever government you did a deal with, that's not the government down the road who decides, I don't care, we're going to come after you anyway.

Speaker 2 So while we kind of saved the system a lot, we bailed a lot of people out, they made us pay $5 billion on the bad mortgages that Bear Stuns had done.

Speaker 2 And that's what made me make the statement I wouldn't do it again. I wouldn't, put it this way, I don't know how to say this, I wouldn't really trust the government again.

Speaker 2 Would

Speaker 2 it,

Speaker 1 I gotta ask a follow-up question to that.

Speaker 1 Is that a

Speaker 1 structural thing, just the way that we're set up with a new administration every four years?

Speaker 2 Yeah, they don't feel obligated to what the prior administration did.

Speaker 2 And, you know, contract, even some contracts were violated in this thing, which I won't go through.

Speaker 2 Literally, contracts. I mean, it would have been tortuous interference had it been company to company.

Speaker 2 But they basically, you know, since you operate under their laws, you know, they can basically take you down.

Speaker 2

So you, you know, I went to see Eric Holder trying to settle all his mortgage stuff, which we settled. I brought my lead director.

He expected me to come and be pounding my chest. And

Speaker 2 I went in and said, Eric,

Speaker 2

I am here to surrender. I cannot fight and I cannot win against the federal government.

You know that a criminal indictment can sink my company. I will not do that to my company or my country.

Speaker 2 I'm here to surrender.

Speaker 2 Before I surrender, I want you to know the circumstances by which we bought Wamu and Bear Stearns, because 80% of what they were asking for related to Bear Stearns and WAMU, not JPMorgan Chase.

Speaker 2 And I went through the whole thing. You know, he said, thank you.

Speaker 2 I'll take it in consideration. But they never gave me the accounting, so I don't know what they did.

Speaker 2 And so it is what it is. It was quite painful.

Speaker 2

But it's got to move on. We'll move on from this.

We'll move on.

Speaker 2 Well,

Speaker 2 we'll move on from the specifics.

Speaker 2 I do have one more thing.

Speaker 2 Whether you would have done it again wouldn't have, you know,

Speaker 2 very clear, it was not a great deal on paper for JPMorgan.

Speaker 2 But as we look at it now,

Speaker 2 the reputational value that JP, the reputation of JPMorgan now is unlike any other in the industry.

Speaker 1 Part of why you're worth $800 billion is that reputation.

Speaker 1 A lot of what created that reputation

Speaker 2 was that weekend. Yeah, I know if you're, yes, and I know I say I wouldn't trust the government, but the government called me up, they did it again.

Speaker 2

If they called me again and said, we need your help to save our country. Well, of course I'm going to, I'm a patriot that way.

I just.

Speaker 2 I would just try to come up with some ways to avoid the punishment by the next president.

Speaker 2 I would come up with something.

Speaker 2 You know what? You need the version of the merger agreement with JP Morgan Chase, where it's like a 75% of Congress needs to vote not to sue you.

Speaker 2

The default is you're not going to get sued. All right.

All right.

Speaker 1

So bear sternance happens. Six months later, you get another phone call.

WAMU is going under. You do buy WAMU.

Speaker 1 Contrary to everything we're talking about with Bearer, WAMU is actually a great acquisition, right?

Speaker 2

Yeah. So this is a lesson about acquisitions.

It's very hard. Remember, we bought WAMU a week after Lehman went bankrupt.

Speaker 2 And

Speaker 2 most boards wouldn't have touched that at all. Because the whole system feels true.

Speaker 2 The whole system was in trouble. But WAMU put us in California,

Speaker 2

parts of Nevada, Arizona, not Arizona, Georgia, Florida, which we weren't in. So think of these really healthy states.

And they had 2,300 branches.

Speaker 2

They had huge mortgage problems. But we had looked at it over and over and over.

So we knew their mortgage books called.

Speaker 2 And we wrote off, we bought it for a million. And this was all before.

Speaker 2 We bought it for a $30 billion discount to tangible book value

Speaker 2

because they had debt and we left the debt behind. And so, and that $30 billion was approximately what the mortgage loss was going to be.

So we bought the company.

Speaker 2

Think of it, we bought a company clean, we wrote off all that stuff. The books were clean.

And then we did something unheard of, too.

Speaker 2 The next day, or two days later, I went in the market and raised another another $11 billion of equity, which I didn't really need. But again, this is my conservatism.

Speaker 2

I was like, you know what? This could get even worse. And I don't want to be short capital liquidity.

So

Speaker 2 we raised that to make sure our balance sheet was just as strong as it was after WAMU, that it was before WAMU.

Speaker 1 And you already had the reputation to pull this off, right? I'm imagining in the worst month of the financial crisis, who can go out and raise $11 billion of equity?

Speaker 1 People trust you.

Speaker 2 Well, yeah, we knew a lot of the shareholders, and you earned your trust over time with shareholders. And we explained, we gave them a quick little presentation over the, you know,

Speaker 2 yeah, and a lot of them stepped up and said, this is great.

Speaker 2 And they also know we can execute it because behind the bear sterns, people forget the work is the next day you got 50,000 people consolidating 5,000 applications, branches, compensation programs,

Speaker 2

settlement programs, payment systems. It's a lot of work.

But we obviously have the capability to do that, and we have the capability to do in WAMU.

Speaker 2 I think we finished the WAMU consolidations in nine months, all of them.

Speaker 2 So that within nine months that we're all in the same systems, which allows you to start doing a better job in customer service and things like that.

Speaker 1 So this Fortress balance sheet strategy and raising this equity capital and having additional margin of safety and conservative accounting, in retrospect, it seems like the obvious right strategy for running a large financial institution.

Speaker 1 Why wasn't everyone else copying it? Have people changed? And does everyone else run their banks like this now?

Speaker 2

I think people, the people are more conservative today. I think regulars are more conservative today.

But again, I go back to people get involved in aggressive accounting.

Speaker 2 They don't look at stressing their own bank in a real way.

Speaker 2 You saw people take too much interest rate risk, too much credit exposure, too much optionality risk,

Speaker 2

or sometimes it's new products. So if you look at the financial services, very very often it's the new products that blow up.

It takes a while. They haven't been through a cycle.

Speaker 2

And you had that with equities way back in 1929. You had it with options.

You had it with equity derivatives. You had it with mortgages.

You had it with Ginnie.

Speaker 2 Even Ginnie Maze at one point blew up, even though they're government-guaranteed.

Speaker 2 Arguably, you had it with Quant and with LTA. It happened with Quant, it happened with leveraged lending.

Speaker 2 And then people then become more rational how they run these balance sheets and how they think through the risk.

Speaker 1 So I have to ask you: is this private credit today?

Speaker 2 Say it again.

Speaker 1 Is this private credit today?

Speaker 2 I don't really think so. I don't think it's $2 trillion.

Speaker 2

It's grown rapidly. That's an issue.

But what happens, the other thing about markets, there's some very good actors in it who know what they're doing. Customers like the product.

Speaker 2 So I always say, well, the customers like it.

Speaker 2

But there are also people who don't know what they're doing. And it's grown rapidly.

So

Speaker 2 there may be something in there that would become a problem one day. I don't think it's systemic.

Speaker 2

So that $2 trillion, the mortgage market when the time it blew up was, I'm going to say $9 trillion, and a trillion dollars was lost. This is, you know, and it was, I know.

A trillion dollars was also

Speaker 2

a market. More than a trillion dollars back then.

Yeah,

Speaker 2 a lot of these private credits are not leveraged like that.

Speaker 2 That doesn't mean there won't be problems, but it's slightly different.

Speaker 2 But you look at the whole system, there are other things out there that, you know, are leveraged that can cause problems. Of course, people take secret leverage in a way you don't necessarily see it.

Speaker 1 What are some of these in your mind that are potentially problematic today?

Speaker 2 Well, look, I look at, when you look at asset price, they're rather high. Now, I'm not saying that's bad, but

Speaker 2 if today PEs were 15 as opposed to 23,

Speaker 2

I say that's a lot less risk. A lot less to fall, and you have some upside.

I would say at 23, there's not a lot of upside, and there's a long way to fall. And that's true with credit spread.

So

Speaker 2 we look at, we stress test everything. We do like 100 stress tests a week, you know, and to make sure we can handle a wide variety of things.

Speaker 2

And then the other thing, and the biggest risk to me is cyber. I mean, I think this cyber stuff is, you know, we're very good at it.

We work with all the government agencies.

Speaker 2

They would say that James said, we spend $800 million a year or something on it. We educate people on it.

We just do.

Speaker 2 But it is, you're talking about grids and communications companies and water

Speaker 2 and even part of the military establishment. The protections are not what you need if we ever get any kind of war where cyber is involved.

Speaker 2 And China is very good at it, and so is Russia, but Russia is mostly criminal, which is slightly different.

Speaker 2 All right.

Speaker 1 I'm going to pull us back to the story. We're going to fast forward to 2023.

Speaker 2 We're not really equipped to talk about Russia.

Speaker 2 It's not what we do on acquired, but

Speaker 1 Silicon Valley Bank

Speaker 1 and First Republic both fail.

Speaker 2 You're there again.

Speaker 1 Did you see it coming? What lessons did you learn from how 2008 went that you could apply in 2023? Obviously, you you bought First Republic.

Speaker 2

It's a Silicon Valley Bank. Both Silicon Valley Bank did some very good stuff.

But

Speaker 2

they both had something unique that we didn't know at the time. I'm going to call them concentrated deposits.

Not uninsured, because people have misstating that, concentrated.

Speaker 2 And so a lot of venture capital. And what happened with Silicon Valley Bank and kind of First Republic is some of these large venture capital companies

Speaker 2 calling their hundreds of them, maybe a thousand, told their constituent clients that they invested in, who all banked in Silicon Valley and First Republic, the banks aren't safe, get out.

Speaker 2 And they all removed their deposits. And Silicon Valley Bank, I think they had 200 billion deposits, 300 billion, 100 billion in one day.

Speaker 2

And that caused the problem, but they also had other problems. They didn't have proper liquidity.

They didn't have their collateral posted at the Fed.

Speaker 2

And they had taken too much interest rate exposure. And the interest rate exposure was hidden by accounting.

It was called hell to maturity, where you don't have to mark even treasuries to market.

Speaker 2 And I always hated hell to maturity because, but it gives you better regulatory returns and stuff like that. But when that held to maturity,

Speaker 2 if you said, What's the tangible book value of one of these banks? You said it was 100, well, all of a sudden it was 50 if you just mark that one thing to market.

Speaker 2 And there's now here, now you're into judgment land. At what point, if you saw a bank where just that one mark had the tangible book value drop to 40 or 30 cents in the dollar, would you panic?

Speaker 2

I would have said that's too much risk. And the regulators helped this because they said rates are going to stay low forever.

So these banks bought a lot of 3% mortgages.

Speaker 2 And 3% mortgage, when rates went up to 5%,

Speaker 2

worth 60 cents in the dollar or 50 cents. And that was it.

And so both those had, they took too much interest rate exposure, known to management, and it was known to the regulators

Speaker 2 and fixable. So

Speaker 2

we knew a little bit about Silicon Valley Bank. We were trying to compete in that area.

So we learned a lot afterwards about how to do a better job for that ecosystem of venture capital.

Speaker 2

We have a whole campus in Palo Alto now. We've hired 500 innovation bankers.

We cover venture capital companies. We're not as good as they are yet.

Speaker 2

We're going to get there because we're organized slightly differently. And we knew First Republic.

We were watching it. I called Janet Yellen.

I said,

Speaker 2

that company's in trouble and one or two others. If you want to, we'll take a look.

We could probably buy it and eliminate the problem. They waited a little bit too long.

Speaker 2 It was kind of a little melting ice cube. But you can imagine the day we bought it, you never heard about it again.

Speaker 2 We hedged all their exposures in a couple of days and we merged everything, we wrote everything down, and but we did get some good stuff from we actually got some good people.

Speaker 2 You know, the normal thing in acquisition is they're terrible, get rid of them, or they failed. But we also looked at what they did, how they dealt with clients.

Speaker 2 Some of you may be clients here, they did a great job with high-net worth clients. Single point of contact, you know, conscious services.

Speaker 2 So now, if you go down Madison Avenue, you see things called J.P. Morgan Financial Center.

Speaker 1 That's your first JP Morgan-branded consumer effort.

Speaker 2 Yes.

Speaker 2

Because it's kind of based on that. When you walk in there, we know your small business, we know your mortgage, we know your consumer banking.

We can get you travel.

Speaker 2

We can do a whole bunch of different stuff. So we're very high-level services.

I think we have 20 of them now, but I love it. And if it works, you know, in 20 years, we'll have 300.

Speaker 2 And so these things are opportunities, and I hope it works. You don't always know they're going to work for a fact, but so far, so good.

Speaker 1 All right, listeners. Now it is time to talk about one of our favorite companies, StatSig.

Speaker 2 StatSig is the tool of choice for product development teams at hundreds of great companies, including OpenAI, Notion, Rippling, Brex, Atlassian, and more.

Speaker 2 So why are all of these hyper-growth companies using StatSig?

Speaker 1 Well, in the past, every major tech company spent years rebuilding the same internal data tools like feature flags, product A-B testing, logging services, product analytics, dashboards, you name it.

Speaker 1 But the latest generation of great companies are just using StatSig. Yep.

Speaker 2 StatSig has rebuilt the entire suite of data tools that previously was only in use at the biggest tech giants as a standalone product.

Speaker 2 This includes cutting-edge product experimentation, feature flags for safe deployments, session replays, analytics, and more, all backed by a single set of product data.

Speaker 2 It's a holistic suite to build better products.

Speaker 1 Statsig is also warehouse native, so it can plug directly into your existing data in Snowflake, BigQuery, whatever you're using. That means way more privacy and security.

Speaker 1 Great for any finance listeners out there, plus no sending your data to yet another tool.

Speaker 2 So if you're ready to give your product and engineering teams access to great data tools, go to statsig.com/slash acquired to get started. That's s-t-at-t-s-ig-g.com/slash acquired.

Speaker 2 They have a generous free tier and a $50,000 startup program. Just remember to tell them that Ben and David sent you.

Speaker 1 All right, so we're effectively caught up to today. And if we're trying to, and now we've got the whole story, we've got a lot of context.

Speaker 1 Obviously, Lep didn't go into every detail, but if we're now trying to answer, yes, if we're now trying to answer the question, how did you separate from the pack?

Speaker 1 Why did you become a completely different animal than your whole competitive set?

Speaker 1 What are the things in your mind that led to this success?

Speaker 2 Well,

Speaker 2 I mean, I don't know totally. First of all, because we skipped over strategy a little bit, and this is important for you all that

Speaker 2 we have, what we do is the same thing that a community bank does other than investment bank, global investment banking.

Speaker 2 Okay, so if you walk into a small community bank, they know your business account, they know your consumer account, they usually have a trust company.

Speaker 2

They used to call it a trust. They'd manage your private affairs, they'd set up a trust for you, and they'd tour stuff like that.

And their CRM is up here.

Speaker 2 They don't need a Salesforce CRM because they know everyone in town. And they didn't do big-time global investment banking.

Speaker 2 But the strategy, those businesses fit together, they feed each other, and so does investment banking. A lot of our middle market clients use investment banking products.

Speaker 2

A lot of our consumer clients use some FX. So all of our businesses feed each other.

There's no extraneous. We got rid of everything that didn't fit a strategy.

Speaker 2 And then you start building client businesses and client services, fortress balance sheet, fortress accounting, all those various things.

Speaker 2 And I've always talked about...

Speaker 1 So it's holding a portfolio of things that actually feed each other.

Speaker 2 They actually fit. Whereas Citi had

Speaker 2

consumer finance, that didn't fit. Life insurance, that didn't fit.

Property calendar, that didn't. They eventually got rid of them all.

Sandy just wanted to do more of them.

Speaker 2 He bought American General, which did truck leasing, for God's sake.

Speaker 2 I mean, and you know, once you get involved in these things, it's hard for people to understand the risk in each one of these businesses.

Speaker 2

But all of ours fit. I don't like hobbies.

I don't like things.

Speaker 2

And we've made plenty of mistakes because you have to try and test things. And then you're always investing for the future.

That investment is always people,

Speaker 2 branches, and technology.

Speaker 2 And that's true whether investment banking people or consumer bank people are opening consumer branches or I think Doug Penno's here and Troy Rohrbach who run the Global Investment Bank but they've opened you know commercial banking branches all over Europe and I think you're telling me I mean it's it's it's going great you know and it's feeding all other parts of the company so just sticking to your knitting constantly investing you know not overreacting to the market you know markets are like accordions and then sometimes you know it's a when if you're strong when others aren't you have a chance to buy things you want to buy and then always look at the world from the point of view of the consumer what do you want how do you want it how do you want to get it can we provide it to you uh uh in a way that makes sense for us too?

Speaker 2 Not going for the last dollar and nothing like that.

Speaker 2

And building teams of people. Our people are curious and smart.

They have heart, they have soul. They give a damn about

Speaker 2 the guards in the company and the receptionists. And

Speaker 2

it's not just about the big-time bankers and people pounding their chest. We don't try not to put up with that.

And we have big-time bankers. They are exceptional.

Speaker 2 But the company serves the clients, and we have, and I think the clients know that.

Speaker 1 When you really dig in to start analyzing JPMorgan's financials, you kind of see this one thing that jumps right out at you, which is the efficiency ratio.

Speaker 1 For every dollar that you make compared to your competitors, you get to keep 15 cents more of that dollar as profit. It's not hard to see how that compounds and how that allows reinvestments.

Speaker 1 And why is your efficiency ratio so much better than competitors?

Speaker 2 It is literally continuously investing and gaining business at the margin and not stopping and not stop starting. And

Speaker 2 the thing about margins, too, is that we have that margin while investing a lot. It's much easier to have that margin and just, you know, we can cut billions of dollars of marketing out tomorrow.

Speaker 2

We can stop opening branches and save a billion dollars next year. We can do a lot of things.

Your margins will go up. Your growth will go down.

Your long-term margins will probably get worse.

Speaker 2 So we kind of look right through the cycle and we look at the actual economics that we do, not the accounting of what we do.

Speaker 2 And

Speaker 2 we've built it over time. We have great people and great products, and there's some secret sauce I'm not going to tell you about.

Speaker 2 We do Investor Day, and we tell everyone everything, and I'm sitting there watching my, I never do presentations, I'm watching them do the presentations.

Speaker 2 I'm saying, oh, God, we're just giving away too many secrets here.

Speaker 2 So there's secrets as to why the efficiency risks. Well, you know, I saw Howard Schultz here before, you know, and I'm not supposed to say that probably.

Speaker 2

It's okay. It's okay.

But

Speaker 2 no, but

Speaker 2 look what he built over the years.

Speaker 2 The consistency, the curiosity, the heart,

Speaker 2

branch by branch products. It's just always doing that, knowing you're going to make mistakes, but building the culture that just kind of plows through that.

And you all know, I do use sports.

Speaker 2 Sports is a great analogy. If you have a sport team with a bunch of real jerks on it, are they going to be a great team?

Speaker 2 Almost never. You know,

Speaker 2 if the team members aren't giving it their best every day during practice, you literally to Tom Brady, every day at practice he worked hard.

Speaker 2

You know, if people are not giving their best, you're going to have a great team. It's not that different in business.

The difference in business, you can BS about it all the time.

Speaker 2 You can make up stories. But in sports, you see it on the playing field.

Speaker 2

Do they have the team? Do they play together? They don't even have to be friends. They have to practice, know their teams.

And so I do think companies have that. It's like a sauce that works.

Speaker 2 And you've seen it lots of different companies, not just JP Morgan Chase.

Speaker 2 So, all right, we've got one last question for you.

Speaker 2 If you look back to 2008, which was a long time ago now. To 2001? To 2008, which was a long time ago now.

Speaker 2

All of the other leaders that were involved in that era have long since retired. I mean, I think many folks within J.P.

Morgan Chase have long since retired since then.

Speaker 2 It seems like you're working as hard as ever and in it as much as ever.

Speaker 2 Why are you still here? What keeps you going? Yeah.

Speaker 2 So I want to thank my wife who's here too, who suffered through all this with me all these years and probably couldn't have done it,

Speaker 2 couldn't have done it without her.

Speaker 2 Look,

Speaker 2 I don't know, but I do believe

Speaker 2 my grandparents, all Greek immigrants,

Speaker 2 my grandparents, all Greek immigrants who didn't finish high school.

Speaker 2 But there's a Greek ethic, you know, which I, and you don't even realize you're learning from your parents, you know, from the ground up And Judy's parents, my wife's parents were the same, which is, you know, have a purpose.

Speaker 2 You know, have that, it could be art, it could be science, it could be military, it could be business, it could be, it could, it could be just being a great parent, a great teacher, you know, but have a purpose and then do the best you can.

Speaker 2

You know, give it, give it your all. Don't like be one of those people who's complaining all the time.

You know, you give it your best and

Speaker 2

then treat everyone properly. Everyone.

You know, like I, if I,

Speaker 2

including like if there's a bully beating up on someone, you had to stand up for someone. You were not allowed to allow a bully to do it.

So how you treat people, what you do.

Speaker 2 And so in my hierarchy of life, the most important thing is my family.

Speaker 2 It still is. The second thing is my country, because I think this country is the indispensable nation that brought freedom of speech, freedom of religion, freedom of enterprise,

Speaker 2 which we have to teach everywhere we go about how important it is. I don't think people fully understand it sometimes.

Speaker 2 And then my purpose, because my affiliates want me home every day and this is this is my contribution through this company I can help cities states schools companies employees and I get the biggest kick out of that and so that's what I do and as long as I have the energy I'm gonna do it I can't imagine I'm not I don't play golf you know

Speaker 2

my daughter one of my daughters said dad you need some hobbies and I said I do we hanging out with you, family travel, barbecuing and wine, we now like whiskeys. And I love reading.

I love history.

Speaker 2 I think history is the greatest teacher of all time. Hiking, I can't play tennis anymore because my back, but those are my hobbies.

Speaker 2 I don't buy fancy cars and stuff like that, but this gives me purpose in life beyond family and beyond country. Plus, I think this helps the country.

Speaker 2 You know, I get to do a lot of things for our country that I just think are quite meaningful from this job. And so when I'm done with this, I don't know, I'll teach and write.

Speaker 2 I may write a book like Andrew Orsorkin did.

Speaker 2 I'll do something, but I got to do something. I'm not going to twiddle my thumbs and smell the flowers.