114: HD

HD Moore (https://twitter.com/hdmoore) invented a hacking tool called Metasploit. He crammed it with tons of exploits and payloads that can be used to hack into computers. What could possibly go wrong? Learn more about what HD does today by visiting rumble.run/.

Sponsors

Support for this show comes from Quorum Cyber. They exist to defend organisations against cyber security breaches and attacks. That’s it. No noise. No hard sell. If you’re looking for a partner to help you reduce risk and defend against the threats that are targeting your business — and specially if you are interested in Microsoft Security - reach out to www.quorumcyber.com.

Support for this show comes from Snyk. Snyk is a developer security platform that helps you secure your applications from the start. It automatically scans your code, dependencies, containers, and cloud infrastructure configs — finding and fixing vulnerabilities in real time. And Snyk does it all right from the existing tools and workflows you already use. IDEs, CLI, repos, pipelines, Docker Hub, and more — so your work isn’t interrupted. Create your free account at snyk.co/darknet.

Press play and read along

Transcript

Speaker 1 Did you know that in 1982, a robot was arrested by the police?

Speaker 1

Yeah, get this. It was standing on North Beverly Drive in Los Angeles, and it was there handing out business cards to people.

It could talk too, and it was telling people random robot things.

Speaker 1

Well, it was causing a commotion. People were just standing around it staring.

Traffic jams, honking. It was making a scene.

The police wanted to put a stop to it.

Speaker 1 They looked around and in the robot to try to find who was controlling it, but they couldn't figure it out. So they started dragging it off, and the robot started screaming, Help!

Speaker 1

They are trying to take me apart. The officer disconnected the power source and took the robot into custody.

They put it in the cop car and drove it down to the Beverly Hills police station.

Speaker 1 It turned out it was two teenage boys that were remotely controlling it. They borrowed their father's robot to pass out his robot factory business cards.

Speaker 1

It's funny how time changes our interest in things. If a robot stood on the same corner today, handing out business cards, it would hardly be noticed.

But in 1982, that was quite the scene.

Speaker 1 Sometimes it just takes us a while to get accustomed to the future.

Speaker 1 These are true stories from the dark side of the internet.

Speaker 1 I'm Jack Reesider.

Speaker 1 This is Darknet Diaries.

Speaker 1 This episode is sponsored by my friends at Black Hills Information Security. Black Hills has earned the trust of the cybersecurity industry since John Strand founded it in 2008.

Speaker 1 Through their anti-siphon training program, they teach you how to think like an attacker.

Speaker 1 From SOC analyst skills to how to defend your network with traps and deception, it's hands-on, practical training built for defenders who want to level up.

Speaker 1 Black Hills loves to share their knowledge through webcasts, blogs, zines, comics, and training courses all designed by hackers, for hackers.

Speaker 1 But do you need someone to do a penetration test to see where your defenses stand? Or are you looking for 24-7 monitoring from their active SOC team?

Speaker 1

Or maybe you're ready for continuous pen testing where testing never stops and your systems stay battle ready all the time. Well, they can help you with all of that.

They've even made a card game.

Speaker 1

It's called Backdoors and Breaches. The idea is simple.

It teaches people cybersecurity while they play. Companies use it to stress test their defenses.

Speaker 1 Teachers use it in the classroom to train the next generation. And if you're curious, there's a free version online that you can try right now.

Speaker 1 And this fall, they're launching a brand new competitive edition of Backdoors and Breaches, where you and your friends can go head to head hacking and defending just like the real thing.

Speaker 1 Check it all out at blackhillsinfosec.com/slash darknet. That's blackhillsinfosec.com/slash darknet.

Speaker 1 This show is sponsored by Delete Me.

Speaker 1 DeleteMe makes it easy, quick, and safe to remove your personal data online at a time when surveillance and data breaches are common enough to make everyone vulnerable.

Speaker 1 Delete Me knows your privacy is worth protecting. Sign up and provide DeleteMe with exactly what information you want deleted, and their experts will take it from there.

Speaker 1 DeleteMe is always working for you, constantly monitoring and removing the personal information you don't want on the internet.

Speaker 1

They're even on the lookout for new data leaks that might re-release info about you. Privacy is a super important topic for me.

So a year ago, I signed up.

Speaker 1 Delete Me immediately got busy scouring the internet looking for my name and gave me reports of what they found. Then they got busy deleting things.

Speaker 1 It was great to have someone on my team when it comes to protecting my privacy. Take control of your data and keep your private life private by signing up for Delete Me.

Speaker 1 Now at a special discount for my listeners, get 20% off your Delete Me plan when you go to joindeleatme.com slash darknet diaries and use promo code dd20 at checkout the only way to get 20 off is to go to joindelete me.com slash darknet diaries and enter code dd20 at checkout that's join delete me.com slash darknet diaries code dd20.

Speaker 1 You ready to get into it? Do you have your sixth cup of coffee today?

Speaker 2 I did, yeah. I finished the whole pot.

Speaker 1 You feel, you sound like a guy guy who's just really turned on to like, you know, 11.

Speaker 2 Like

Speaker 1 you talk fast, you, you build things quickly. I mean, it's, it's just moving all the time for you.

Speaker 1 Okay.

Speaker 1 So

Speaker 1 what's your name?

Speaker 2 Uh, H.D. Moore.

Speaker 1 And how did you, um, what was some of the early stuff that you were doing security or hacking-wise when you were a teenager?

Speaker 2 I was an internet hoodlum. Um, got my start on the old, BBS days,

Speaker 2 go to hang out with a friend of mine.

Speaker 2 He'd fall asleep early, leave his Mac there with his various BBS accounts and start dialing around, figure out what he can get to, download the zines, figure out how to dial into all the fun Unix machines in town.

Speaker 1 How to dial into all the fun Unix machines in town? See, back in the 90s, there weren't a lot of websites that you could just spend your time endlessly scrolling through.

Speaker 1 But there were a bunch of computers configured to accept connections from outsiders.

Speaker 1 And the way to connect to these computers wasn't over the internet, but simply to dial up that phone number directly and see if a computer picked up.

Speaker 1 And if a computer picks up, now it's time to figure out what even is this machine and why is it listening to people dialing into it?

Speaker 1 And you could find some weird stuff listening for inbound connections. Stuff you probably shouldn't be getting into, but the system just was not configured to stop anyone.

Speaker 1 HD lived in Austin, Texas, and was curious to find if any computers were listening for connections in his town. So he started dialing random numbers to see if any would be picked up by a computer.

Speaker 2 At one point, my mother was working as a medical transcriptionist.

Speaker 2 And the great thing, you know, kind of, you know, early days of internet is that to do that, we had to have a whole lot of phone lines going to the house. We had two or three regular pots lined.

Speaker 2

We had an ISDM line and two computers. And, you know, she went to bed pretty early.

So as soon as she was down, I was up.

Speaker 2 And I was running tone log across the entire 512 area code pretty much every night for years.

Speaker 2 And then whenever you find something interesting, try to figure out what it is and what you can do with it.

Speaker 2 Some of the fun highlights from back then are like turning the HVAC on and off at the various department stores, dialing into some of the radio transmission towers and playing with that stuff.

Speaker 2 You know, this is

Speaker 2 obviously well before I was like 18 and was too concerned about the consequences. But just that whole process really got me into security, security research, and eventually, you know, the internet.

Speaker 1

This was really fun for HD. Poking around in the dark, trying to find something interesting, and then getting lost in that system for a while.

He was fascinated by it all.

Speaker 1 Eventually, the internet started forming a little more, and IRC picked up in popularity. This was just a chat room, and HD was spending a lot of time in the Frack chat channel.

Speaker 1 Now, Frack is the longest-running hacker magazine. The first issue was published in 1985, and by the 90s, they had quite a trove of information.

Speaker 1 If you wanted to learn how to hack or break computers, start by reading every issue of Frack, and by the time you're done, you'll be pretty knowledgeable of hacking.

Speaker 1 So the FRAC chat channel felt like home to HD, and he loved hanging out there, learning about hacking.

Speaker 2 We're all using our silly aliases and playing with exploits and generally causing havoc between each other. And out of the blue, I get a message from somebody saying, hey, you're looking for a job.

Speaker 2

I'm like, yeah, actually, I am. And he's like, well, you're not too far.

How far are you from San Antonio? I'm like, well, I could drive there.

Speaker 2 So he sent me the interview with the Computer Sciences Corporation, which is now just called CSC.

Speaker 2

And they were doing work for, I think at the time it was called AFWIC or it eventually became AIA, but the Air Intelligence Agency. So U.S.

Air Force's

Speaker 2

intelligence wing. And they were basically building tools for various red teams inside the Air Force.

And I was like, that sounds like a lot of fun writing exploits to the military.

Speaker 2

I'm all about that. So I was a really terrible programmer and I'm not much of a better one these days.

But it was a fun first job to go down there and

Speaker 2 get these somewhat vague briefs about we need a tool that listens on the network for packets and does these things with them, or scans network looking for open registry keys and does this other stuff.

Speaker 2 So that was my first kind of professional experience of building offensive tooling.

Speaker 1 I think it's kind of weird that a recruiter for a DOD contractor was looking in the frack chat room to find people to come build hacker tools in order to test the defenses of the Air Force.

Speaker 1 But that's what happened. HD was now using his hacking skills for good.

Speaker 1 And while he was in high school, even at some point while working for this contractor, they asked him to see if he can hack into a local business.

Speaker 1 That business had actually paid for a security assessment and wanted to see if they were vulnerable.

Speaker 2

And it was a lot of fun. We basically just walked in and owned everything.

It was great. Outside, inside, you know, their HP 3000 servers, everything between.

had a blast doing it.

Speaker 2

And we went back to CSE and say, hey, we'd like to start doing more commercial pen tests. And they came back and said, nope, we're federal.

That's it. So we took the whole team and started a startup.

Speaker 2 That was digital defense.

Speaker 1 HD loved doing security assessments for customers and this is a penetration test.

Speaker 1 Customers would hire them to see if their computers were vulnerable and they did other things too, like monitoring for security events and help secure the network better.

Speaker 1

But there was a problem, a big one, if you ask me. Back in the late 90s, exploits were hard to come by.

See, let me walk you through how a typical pen test works.

Speaker 1 First, you typically want to start out with a vulnerability scanner.

Speaker 1 This will tell you what computers are on the network, what services are running, what apps are running, and maybe even give you an idea of what versions that software is running too.

Speaker 1 Because sometimes when you connect to that computer, it'll tell you what version of software it's running.

Speaker 1 Now, as a pen tester, once you know the version of an application that a computer is running, you can go look up to see if there's any known vulnerabilities.

Speaker 1 Maybe that's an old version that they're running. And here's where the problem lies.

Speaker 1 Suppose that, yes, you did find a system that was not updated and was running an old version of software that has a known vulnerability.

Speaker 1 It's simply not enough to tell the client that their server is not patched and needs to be updated. The client might push back and say, well, what's really the risk for not updating?

Speaker 1 And so that's why a pen tester has to actually exploit the system to prove what could go wrong if they don't update. They need to act like an adversary would.

Speaker 1 But to get that exploit, so that you can demonstrate to the client that this machine is vulnerable, that's the hard part. At least it was in the 90s.

Speaker 1 Some hacker websites would have exploits that you could download, but those were often pretty old and out of date.

Speaker 1

So then you might start feeling around in chat rooms, trying to see who's got the goods. And if you're lucky, you get pointed to an FTP server to download some exploits.

But it has no documentation.

Speaker 1 And who knows what this exploit does? It could be an actual virus.

Speaker 1

And as a professional penetration tester, you really can't just download some random exploit from the internet and launch it on your customer's network. No way.

Who knows what that thing does?

Speaker 1 It could infect the whole network with some nasty virus or create some back door that other hackers can get into. So back then, there just wasn't a place to get good exploits from.

Speaker 1 And especially there wasn't a place to get the latest and greatest ones.

Speaker 2 As you start rolling into the 2000s, what happened is all the folks who previously were sharing their exploits with the researchers, with kind of the community, they all basically started either just getting real jobs and stopped sharing their tools, or they thought there was ethical issues with that.

Speaker 2 But basically it all dried up. It turned into some commercial firms like Core Impact was started around the same time to commercialize exploit tooling.

Speaker 2 Other folks just decided they weren't doing it anymore or they got in trouble.

Speaker 2 And so if you're a security firm trying to do pen tests for your customers, it was really difficult to get exploits back then, really difficult to know whether they're safe or not without rewriting every bite of shellcode from scratch.

Speaker 2 And so the challenge of just getting the right tools and exploits, you had to build a lot of it in-house.

Speaker 1 Well, this company that he was working for didn't really have the ability or expertise or resources to develop their own exploit toolkit.

Speaker 1 But HD, being someone who's fiercely driven and part of this hacker culture, was acquiring quite a bit of exploits and learning how they worked and was able to code some of his own.

Speaker 1

But these exploits were unorganized. They were scattered all over his computer.

The documentation wasn't there. It was hard to share it with some of his teammates.

Speaker 1 And that's why HD Moore decided to make Metasploit.

Speaker 1 Metasploit is an exploit toolkit, which basically means it's a single application that has loads of exploits built into it.

Speaker 1 So once you load it up, you can pick which exploit to use, input some parameters, and launch it on the target. It was not so great.

Speaker 1 But it was a basic collection of vulnerabilities that HD knew and could trust that weren't filled with viruses. This little tool he built was helping him do security assessments.

Speaker 1 And now that he's made a framework, he can continually add new vulnerabilities to make it better. But there are new vulnerabilities being discovered all the time.

Speaker 1 So it was an endless job to keep adding stuff to Metasploit.

Speaker 2 Yeah, I mean, this is a combination of like finding vulnerabilities myself, sharing with friends, reporting some of them, not reporting others the time, and then just being my friends sharing exploits all day long.

Speaker 2 And I wrote some that weren't very good, but I'd write stuff all the time.

Speaker 2 And then you get access to one of the really interesting ones or really high-profile ones and play with a little bit and see what you can do with it.

Speaker 2 What ended up being the first version of Metasploit was very menu-based, very terminal-based, where you kind of picked the exploit, pick the NOP encoder, the exploit encoder, and the payload and put them all together and then send it.

Speaker 2 By the time we got to Metasploit 2, we threw all that out the window and came up with ideas that you can assemble an exploit like Legos.

Speaker 2 So it wasn't, you know, prior to this, most exploits had maybe one payload, maybe two payloads.

Speaker 1

Yeah, a payload. A payload is what you want your computer to do after a vulnerability gets exploited.

Imagine a needle and syringe. The needle is the exploit.

Speaker 1

It gets you past the defenses and into the system. But an empty syringe does nothing.

The payload is whatever's in the syringe, the thing that gets injected into the computer after it's penetrated.

Speaker 1 So what is a typical payload?

Speaker 1 Well, it could be to open the door and give you command line access, or it could be to upload a file and execute it on that computer you just got into, or it could be to reboot the computer.

Speaker 1 The exploit is the way in, and the payload is the action taken once you get in. And yeah, the exploits that you would get your hands on back then, they had like built-in payloads.

Speaker 1 Changing the payload wasn't always even an option, unless you had access to the source code of the exploit and could build your own payload.

Speaker 1 And even even if you did that, what happens the next time when you want to use that exploit with a different payload?

Speaker 1 You'd have to recompile the whole thing with something new and then fiddle with it to get it to actually work.

Speaker 1 And of course, you don't want to run some payload that someone else made on one of your customers' computers unless you can examine the source code and see what it does.

Speaker 1 HD saw this was a problem and modularized how you build an attack. He made this easy with Metasploit, giving you the option to pick the exploit, pick the payload, and then choose your target.

Speaker 1 It made hacking a thousand times easier.

Speaker 2 So instead of being stuck with one payload to one exploit, you could take any payload, any exploit, any encoder, any NOP generator, and stick them all together into a chain.

Speaker 2

And it was great for a bunch of reasons. A lot more flexibility during pen test.

You could experiment with really interesting types of payloads that were non-standard.

Speaker 2 And because everything is randomized all the time, a lot of the network-based detection tools couldn't keep up.

Speaker 1 Because everything was randomized? This is actually a really clever thing he added to the tool.

Speaker 1 So if you put yourself in a defender's shoes, they obviously don't want exploits being run in the network. And they want to identify them and not let those programs run, right?

Speaker 1 And a defender might even make a rule in the antivirus program that says, hey, if there's a program that is this size and has this many bytes and is this long and it's called this, then it's a known virus.

Speaker 1 Do not let this program run. Well, what Metasploit did was randomize all these parts.

Speaker 1 They'd give it a random name and a random size and all kinds of random characters simply so that antivirus tools would have a hard time detecting it.

Speaker 1 And it makes sense for Metasploit to try to evade antivirus because securing your network should be multi-layered.

Speaker 1 The first layer would be to make sure the computers in your network are up to date and on the latest patch. And then the next layer should be to have them configured correctly.

Speaker 1 If both of those fail, then antivirus can inspect what's happening and try to stop an attack in progress. But if antivirus is blocking it, it hasn't even tested whether that system is secure or not.

Speaker 1 So it needs to go around antivirus tools to actually test the server. And a good pen tester will test multiple layers to make sure each layer of defense is actually working.

Speaker 2 So by definition, Metasploit was evasive by default.

Speaker 1 Now, at the time, HD was using this tool to conduct penetration tests on people who wanted to see if their network was hackable.

Speaker 1 HD was one of the initial people to join this company, but he wasn't in any sort of leadership role or a manager or anything.

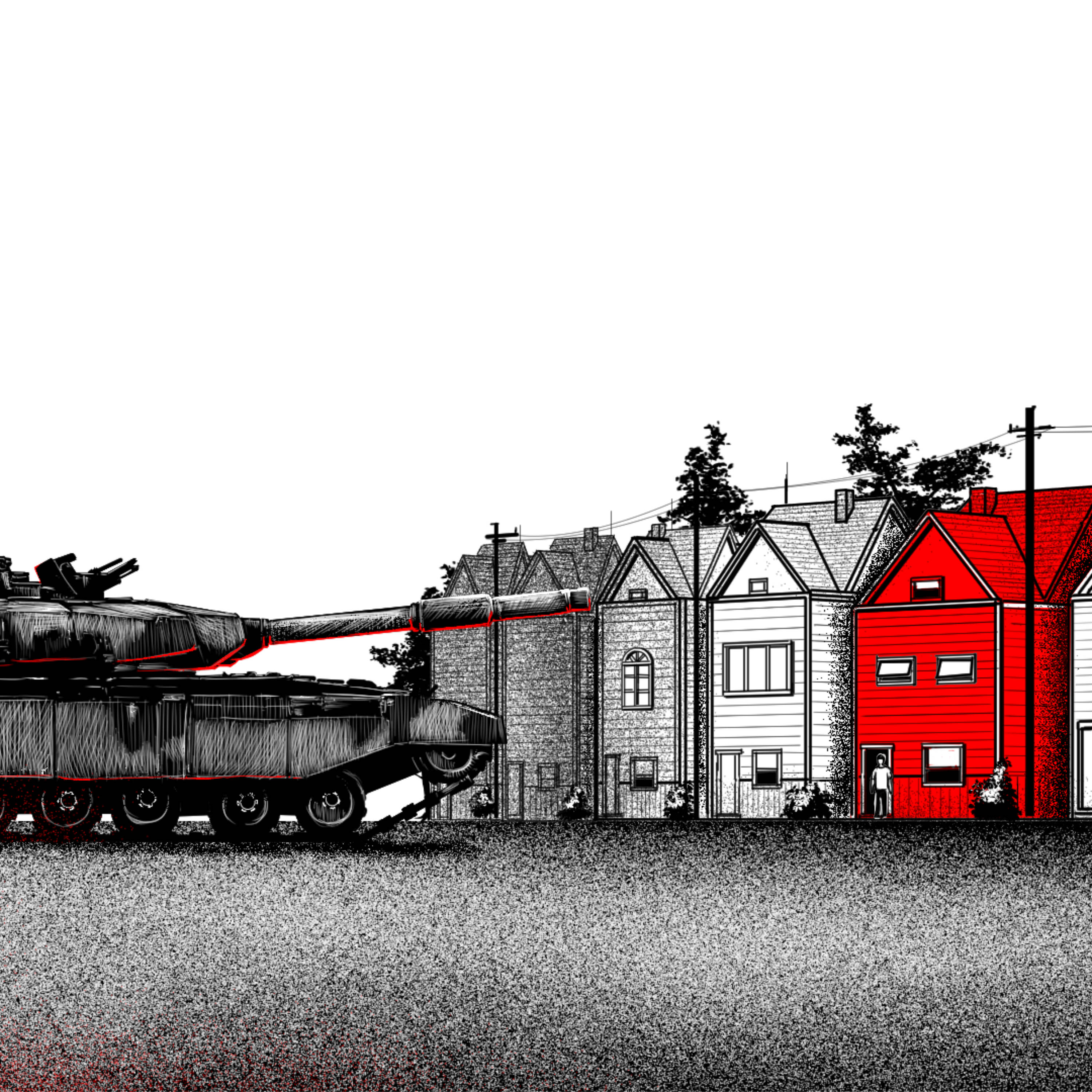

Speaker 1 So imagine for a moment you're HD's boss, and HD shows you this homebrew exploit toolkit, which is programmed to seek out and exploit known vulnerabilities in computers and payloads built into it.

Speaker 1 Now, clearly, in the right hands, this is a weapon. It's an attacker's dream come true.

Speaker 1 Some of the vulnerabilities in it are high quality and make them very dangerous, giving you access to pretty much anything at the time.

Speaker 1 Him bringing in Metasploit to work was like bringing in a bucket of hypodermic syringes with their safety caps off. And some of these were picked up off shady underground places.

Speaker 1 Some of them were DIY homemade. And with syringes, you typically see them in the hands of highly skilled professionals like doctors or people who need beneficial medicine or drug addicts.

Speaker 1

So a bucket of syringes can be extremely dangerous or extremely beneficial. There's no real middle ground.

And it was the same with Metasploit.

Speaker 1 It was a bucket of some pretty scary exploits that if he let loose in the office would be a pretty big problem.

Speaker 1 So bringing in a toolkit like this to work, well, HD's employer was not supportive of this tool.

Speaker 2 I guess more accurately, they were terrified of it. They did not want to be associated with anything I was working on.

Speaker 2 And at the same time, they were kind of stuck with me because I was running most of the pen test operations.

Speaker 1 Why were they terrified of it?

Speaker 2 There's a lot of fear of exploits and liability.

Speaker 2 The worry was that if we released an an exploit and something, you know, someone bad used it to hack in somebody else, somehow my company had become liable.

Speaker 2 So they wanted to stay as far away from it as they possibly could. It didn't help that our primary client base were credit unions, which were kind of naturally conservative and probably still are.

Speaker 2 They didn't want to know that the people that they hired for security assessments were also releasing and open sourcing exploit tools on the internet.

Speaker 1 This is an interesting dichotomy, isn't it? On one hand, if you're going to be testing if a company is hackable, you need these attack tools, these weapons.

Speaker 1 But nobody ever asks a pen tester, where are you going to get your weapons from? They just assume since you're a hacker, you know how to do it.

Speaker 1 But it's not like you can just type a few commands to get around some security measures. That's like reinventing the wheel every time you want to do an assessment.

Speaker 1 You need tools for the job, a set of attacks that you know work well and you can trust that won't put malware on your customer's network or cause harm. But that's a lot of work to make sure of.

Speaker 1 And if you make a hacking tool like this for yourself and maybe put it out there for someone else to use, well, that does sound like it could come back and bite you.

Speaker 1 If someone uses it to actually commit a crime with, how much are you liable for that? So he had to make a decision on what to do with this Metasploit tool.

Speaker 1 If his work wasn't going to help him with it, what should he do with it?

Speaker 2

Well, it's one of those things where, on one hand, they wouldn't support it. On the other hand, we desperately needed this tool to do our job.

And it became a nights and weekends thing.

Speaker 2 So I'd clock out of work and I'd go spend the rest of the night not sleeping um working on exploits working on shellcode and not particularly good exploits but i got better eventually and finally got to the point that we had something that was like worth using all on its own that wasn't just a crappy script equal or like a rewrite of a bunch of known exploits it was actually something that had some legs to it and you know the that led to i think my first trip was to hack the box malaysia to talk about it um

Speaker 2 and it was a great experience to really get feedback about how different it was from what other people were doing at the time that really kind of helped kind of give me motivation to keep working on it.

Speaker 2

It also helped me find people to work on it with. So I met Spoon M shortly after.

I met Matt Miller, Escape right after that.

Speaker 2 They joined the team and we just kind of kept it going as this kind of side project for the next few years.

Speaker 1 So in 2002 is when he first shared Metasploit with others, which immediately got a few people so interested in it, they wanted to help make it.

Speaker 1 And with a few people helping him, in 2003, he decided to release Metasploit publicly for others to download and use.

Speaker 1 After all, it was providing him a lot of value to do his job better, so it would probably make it easier for other penetration testers to do their job too. He also decided to give it away free.

Speaker 1 And importantly, he made it open source so anyone could inspect the code to verify there's nothing too bad going on in there.

Speaker 2 So Metasploit.com was created.

Speaker 2 And that was where we first started posting some interesting variants of Windows shell code that we came up with that were much smaller than what was available otherwise.

Speaker 2 That eventually that became where we shared the Metasploit framework code. The downside, of course, is it gave everyone else a target to go after.

Speaker 2 So as soon as we started posting versions of Metasploit framework to Metasploit.com, we started getting DDoS attacks, exploit attempts. It got so bad that one guy actually couldn't hack our server.

Speaker 2 So he hacked our ISP, ARP spoofed the gateway by hacking the ISP's infrastructure, and then used that to redirect our web page to his own web server.

Speaker 2 So he couldn't hack our web server to face it, but could just redirect the entire ISP's traffic just to build a defaced Metasploit.com.

Speaker 1 Wait, the Metasploit website was getting attacked? By who?

Speaker 2 Well, in the early days, everyone hated Metasploit.

Speaker 2 My employer hated Metasploit, or our customers hated Metasploit. They thought it was dangerous.

Speaker 2 All the Black Hats, all the folks who were trading exploits underground, they absolutely hated it because we're taking what they thought was theirs and making it available to everybody else.

Speaker 2 So it's one of those things where the professionals in the space hated it because they thought it was a script kitty tool.

Speaker 2 The black hats hated it because they thought we were taking away from what they had. And, you know, all the professional folks and

Speaker 2

employers and customers thought it was sketchy to start with. So it took a long time to get past that.

But in the meantime, we're getting DDoS DDoS attacks.

Speaker 2

We're having people try to deface the website. We're having folks spoof my identity and, you know, spoof all kinds of terrible things internet under my name.

You name it.

Speaker 1 Someone decided to attack HD for publishing exploits. They couldn't figure out a good attack on him, so they spent time figuring out where he worked and decided to attack his employer.

Speaker 1

They scanned the websites that his employer had and found a demo site. It wasn't the employer's main site.

It was a tool to demonstrate how to crack passwords.

Speaker 1 Well, this demo site was running the Samba service, but it was fully patched. So there shouldn't be a way to hack into this through the Samba service.

Speaker 1 HD even tried attacking it with Metasploit, but couldn't figure out a way in. But there was someone who did know of a Samba vulnerability.

Speaker 1 They developed their own exploit and attacked HD's employer's website and tried to get inside the system. But their payload didn't work that well and it crashed the server.

Speaker 2 So I got this alert saying the machine was basically shut down and crashed. We're capturing all the traffic going in and out of the machine, just for fun to start with.

Speaker 2 But by doing that, we're able to carve out the initial exploit.

Speaker 1 Wow, this is fascinating. Because HD was capturing all traffic going into and out of that machine, he was able to find the exact code that was used to exploit the Samba service, which is incredible.

Speaker 1 I mean, it's like finding a needle in a haystack.

Speaker 1 But then as he examined this code that was used to exploit the system, he realized this was a completely unknown vulnerability to everyone, which is called a zero-day exploit.

Speaker 1 HD was able to analyze this and learn how to use it himself.

Speaker 2 Did some analysis on it, contacted the Samba team saying, hey, there's a really awful remote O-day in Samba. And so we wrote our own version of that exploit, put it on Metasploit.com.

Speaker 2 And that was kind of the beginning of a long, long war with, I don't even know which group it was, but they spent the next two weeks DDoSing your website for leaking their exploit and not only leaking it, but writing a better version.

Speaker 1

That's brilliant. Because someone didn't like that HD created Metasploit.

They attacked his employer, which made him discover their exploit.

Speaker 1 And he reported that exploit to the Samba team so they could fix it.

Speaker 2 And then he added it into his tool, Metasploit.

Speaker 1 This made his attacker so much more mad at him. And he continued to get attacked like this all the time.

Speaker 2 Folks like emailing my boss telling them to fire me, things like that.

Speaker 2 We've had...

Speaker 1 Yeah, why are people wanting you to be fired?

Speaker 2 They felt that publishing exploits was irresponsible and I was a liability to the company and they didn't want me to have a job because of what I was doing in my spare time. Huh.

Speaker 1 Did they have a point? Did you feel it with them?

Speaker 2 It was good motivations. Try harder.

Speaker 1 Okay. So

Speaker 1 the idea that somebody's going to be upset with a side project you're working on on the weekends to the point where they're going to say,

Speaker 1

I need to get this guy HD. I'm going to ruin him.

I'm going to email his boss and tell his boss to fire him. That That sounds like council culture to me before they even had the term council culture.

Speaker 2 I guess it's not that different. I feel like

Speaker 2 maybe it was the equivalent of a moral ethical dilemma for them at the time. They thought somehow I was doing something like that was morally wrong and therefore needed to be punished.

Speaker 2 But yeah, there's definitely a lot of that.

Speaker 2 There was pressure not just from black hat researchers and from customers who didn't like what I was doing, but also from like other security vendors saying, well, if you want business with us, then you have to bury this vulnerability.

Speaker 2 You can't talk about this one.

Speaker 1 Whoa.

Speaker 1 So when he would find a vulnerability in one of the companies that were a business partner of his employer, that company was absolutely not happy when HD published the exploit and added it into Metasploit.

Speaker 1 Because remember, Metasploit makes hacking so much easier, which means if it's in the tool, it's now easy to exploit that company's products.

Speaker 1 So they'd get mad at him and ask him to take down the blog posts that talk about this vulnerability and remove it from the tool.

Speaker 1 And they would even threaten to take away the partner status that they had with his employer if he didn't comply.

Speaker 1 Things were getting pretty ugly, and his employer was growing increasingly unhappy with HD.

Speaker 1

He was frequently finding himself in the crosshairs of many attacks. But this is his territory.

Hacking, attacks, defending.

Speaker 1 That's what he does during the day as his day job, but it's also what he does at night for fun. And he even dreams about this kind of stuff.

Speaker 1 So if someone attacks AHD more, you know, he's going to have fun with that.

Speaker 2 Uh, what happened is, um, some vulnerability we published was being actively exploited by uh some black guys who were building a botnet, and they were so mad about it, they decided they're going to use that botnet to DDoS Metasploit.com.

Speaker 2 What they didn't realize, though, was like Metasploit wasn't a company, Metasploit was just like a side project I was running in my spare time.

Speaker 2 And I thought the whole thing was hilarious that they were spending all this time DDoSing it. But I did like the fact they're DDoSing an ISP that I liked working with.

Speaker 1 So, this botnet was flooding both of his DNS names, metasploit.com and www.metasploit.com. It was sending so much traffic that this site was unusable by anyone and was essentially down.

Speaker 1 HD investigated this botnet a bit and discovered where the botnet was being controlled from. He found their command and control server or C2 server.

Speaker 2 And they just happen to also have two command and control servers. So, you know, light bulb goes off.

Speaker 2 It's like, well, let's point www.metasploit.com to one of their C2s and the bear domain name to the other one and just sit back and wait a couple of weeks, see what happens, right?

Speaker 2 So what happened is because those are the control servers with the botnet and the botnet was DDoSing its control servers, they got locked out of their botnet until we changed the DNS settings.

Speaker 2 So we essentially hijacked their own botnet to basically flood their own C2 indefinitely until they finally emailed us a week later saying, please can we have it back?

Speaker 1 Wait, what? They emailed you?

Speaker 2 Yeah, because they didn't know how else to get a hold of us. So they basically lost their botnet.

Speaker 2

And we said, okay, well, we'll don't DDoS this again. They went, okay, we won't.

And that was the end of that. And we never got DDoSed again.

Speaker 1 We're going to take a quick ad break here, but stay with us because HD is just getting started with the stories that he has.

Speaker 1

This episode is sponsored by Vanta. In today's fast-changing digital world, proving your company is trustworthy isn't just important for growth, it's essential.

That's why Vanta is here.

Speaker 1 Vanta helps companies of all sizes get compliant fast and stay that way with industry-leading AI, automation, and continuous monitoring.

Speaker 1 So whether you're a startup tackling your first to SOC2 or ISO 27001 or an enterprise managing vendor risk, Vanta's trust management platform makes it quicker, easier, and more scalable.

Speaker 1 Vanta also helps you complete security questionnaires up to five times faster so you can win bigger deals sooner. The results?

Speaker 1

According to a recent IDC study, Vanta customers slashed over $500,000 a year in costs and are three times more productive. Establishing trust isn't optional.

Vanta makes it automatic.

Speaker 1 Visit vanta.com slash darknet to sign up for a free demo today. That's v a n t a vanta.com slash darknet.

Speaker 1 Who do you associate yourself with? Because I'm feeling like you've got like three legs in three different buckets here. And one leg, you're standing in the

Speaker 1 frack, you know, IRC channel, which is black hat hackers typically at the time, right? And these are the people who may be either just, I don't know, hacktivists or cyber criminals proper.

Speaker 1 And then you've got, you know, your relationship with the DOD. And then you've got your professional relationship where you're trying to show yourself, like, look, I've got some real chops here.

Speaker 1

I can do this kind of penetration work for a fee. I'm a professional, you know, this kind of thing.

And I've got actually a tool that I'm developing that can be used for professionals.

Speaker 1 So how do, where, where in this scenario do you like feel like you're most at home?

Speaker 2 Good question. I definitely felt like an outsider in all those groups.

Speaker 2 The Frock channel went through a big change right around 2000 or so, where it used to be some pretty well-respected hacker researcher types and got taken over by a group of trolls that called themselves FRAC High Council.

Speaker 2 And those folks and I did not get along. And that led to this multi-year, just constant trolling and chaos and things like that.

Speaker 2 Even professionally, though, I didn't really have anyone I could really hang out with besides my coworkers and have some good friends there. But there wasn't.

Speaker 2 I almost kind of felt like an outsider in all three of those camps, I guess.

Speaker 1 Yeah, because I know know about this sort of infighting in the kind of the hacker communities when a hacker thinks they they're hot stuff, they post something, they make a website, whatever.

Speaker 1

Other hackers will try to dox them and attack their website. And it's just constantly doing that.

Did you feel like that's kind of what this was? Was just hacker versus hacker?

Speaker 1

Like, look, I'm a smarter hacker than you are. Or did it feel like, no, you're not one of us.

Get the hell out of here kind of attack?

Speaker 2

It definitely wasn't friendly. You know, some friends and and I would always like go after each other's stuff, and it wasn't a big deal.

You say, hey, look, check your home directory.

Speaker 2 There's a file there or whatever it is, right?

Speaker 2 But these are folks who they would steal your mail spool, they'd publish on the internet, they would forge stuff on your name, they try to get you fired, they try to get you arrested, they do everything.

Speaker 2 This is prior to swatting, of course, but this was pretty much everything they could do to ruin your life. This was no holds barred, we're ruining you, and you know, good luck fighting back.

Speaker 2 Um, so this is definitely not the fun kind.

Speaker 1 Now, by this point, HD and the team working on Metasploit Metasploit have found lots of new unknown vulnerabilities themselves, stuff that the software maker has no idea is even a problem.

Speaker 1 And they do this by scanning the internet, attacking their own test servers, and trying to break their own computers. But what do you do when you find an unknown vulnerability in some software?

Speaker 1 Well, the best avenue is to find a good way to report it to the vendor, right? But HD has had a bit of a history with reporting bugs to vendors.

Speaker 2 When I was in teenage years and still kind of at high school, uh i was working on a bunch of the nt4 exploits for fun like the old hdr buffer for flow and things like that and you know while i was plotting around one day i found a way to bypass their uh country validation for downloading i think it was like nt service pack for from microsoft so instead of it looking at your ip address doing geolocation it'd look at a parameter you put in the url instead and you can basically download you know the high encryption version of nt sv6 from russia or wherever else which you know was not a good thing at the time because of all the export controls so i contacted the microsoft security team which is pretty nascent back then and said hey you can like bypass all your export controls.

Speaker 2 This is probably not good. And they're like, Well, what do you want? I'm like, I didn't really want anything, but what do you got?

Speaker 2 And they said, Well, what are you looking for? I'm like, Can I have an MSDN license? That'd be awesome, you know.

Speaker 2 And that was kind of the beginning of a long series of just really weird interactions with the security team there. Fast forward.

Speaker 1 I'm trying to remember what an MSDN license was.

Speaker 2 MSDN was the license that gave you access to all the operating system CDs and media for everything Microsoft made.

Speaker 2 So if you had an MSDN license, you basically have a, you can install any version of Windows you want, any version of Exchange server, all that stuff.

Speaker 2 So as a hacker or someone doing security research, it was a gold mine because you have all the bulk installers and data all in one place.

Speaker 1 Got it. Okay.

Speaker 2 So, you know, fast forward to my first startup and finding vulnerabilities in Microsoft products and doing a lot of work on like ASP.NET misconfigurations and other stuff we've run into during pen testing.

Speaker 2

And Microsoft did not like having vulnerabilities reported. They do anything they can to shut you up.

They did not like having someone releasing exploits for vulnerabilities in their platform.

Speaker 2 The first startup I worked at was on Microsoft Partner. So we had a discount for MSDN and things like that for internal licenses.

Speaker 2 And a gentleman at Microsoft kept calling our CEO saying, hey, you need to stop letting this guy publish stuff. You need to fire this person or we're going to take away your partnership license.

Speaker 2 And so they kept putting pressure on my coworkers, on my boss, and the CEO to get rid of me, basically, because of the work I was doing to publish vulnerabilities. And that just made me angry, right?

Speaker 2 Like I had got to chip my shoulder pretty early on about that.

Speaker 2 And by the time I got to the Hack of in the Box contest in Malaysia to announce Metasploit, they had a Windows 2000, was it Windows 2003 server? I think it was being announced at that time.

Speaker 2 And they had a CTF for it. I was like, great, I'll do the CTF.

Speaker 1 So CTF stands for capture the flag. It's a challenge that a lot of these hacker conferences have, where they put a computer in the middle of the room and see who can hack into it.

Speaker 1 In this case, it was a fully patched Windows computer, and HD was curious if he could find a vulnerability to get into it.

Speaker 1 So he created some tools to send it random commands and inputs, anything that he could send to it to just try to cause it to malfunction.

Speaker 1 And sure enough, he did get a fully patched Windows computer to malfunction.

Speaker 1 So he examined the data that he sent to this computer to cause it to malfunction, and he was able to use that to create an exploit, which got him remote access to the system.

Speaker 1 Now, since this was an unknown bug to Microsoft and Microsoft was there at this hacker conference sponsoring the the thing. He went up to them and told them about it.

Speaker 2

They're like, great, report it to us. I'm like, no, it's mine.

Like, am I going to get a reward for it? What are you going to do with it? Like, I found this vulnerability. It's mine.

Speaker 2

Do what I want to with it. And so I reported it to the Hackinbox.

Like, hey, Microsoft's trying to pressure me to not disclose this thing that I found. Like, that's not the point, right?

Speaker 2

The point is, yeah, I found a bug in your server and I'm going to talk about it. Like, and I'm going to share it with you.

But the idea is to go publish it afterwards.

Speaker 2 And they shut the whole thing down. So I heard secondhand that Microsoft threatened to pull sponsorship of the Hack and Mucks conference if they let that vulnerability get published.

Speaker 2 So the whole thing got swept under the rug.

Speaker 1 See, at the time, Microsoft didn't take their security as seriously as they should. They weren't publishing all the bugs that they were finding or rewarding people for the bugs they found.

Speaker 1 And as HD tells it, they were asking people to not publish bugs publicly. They thought it was just better to hide some of these attacks so that nobody knows about it.

Speaker 1 But around this time in 2002, Bill Gates sent a famous memo to everyone at Microsoft, which said, security is now now a priority of the business and they started a new initiative called the Trustworthy Computing Group.

Speaker 1 Well HD saw that this bug he found was causing problems with the conference and he liked the conference and didn't want them to lose their biggest sponsor.

Speaker 1 So he agreed to just sit on this bug and do nothing with it. Six months later, someone else found the same bug and reported it to Microsoft and they were able to fix it.

Speaker 1 And it was only then that HD published his version of it.

Speaker 2 So the short version is I'm more than happy to tell the vendors about it, but I'd also want to make it public at some point.

Speaker 2 Like these are vendors that at the time were sitting on vulnerabilities for more than a year or two years, maybe never disclosing it.

Speaker 2 They had no motivation to ever disclose a vulnerability you reported to them and they would do anything they could to pressure you not to.

Speaker 2 Microsoft was probably one of the biggest offenders at the time of pressuring researchers to not disclose any vulnerabilities they found.

Speaker 1 Do you know if there was a even like a vulnerability list that they had published at the point at that time?

Speaker 2 I think Microsoft, I mean there were CBEs at the time time and Microsoft had their security advisories, but the security advisories were just the tip of the iceberg.

Speaker 2 There was so much stuff being reported to them that they would just shut down.

Speaker 2 The challenge with keeping these secret, whether it's because you're the vendor and don't want people to know about it and it's bad marketing, or whether you're a black hat and trying to use it to break into systems, is that nobody else out there can protect themselves.

Speaker 2 They can't test themselves. They don't know whether they're actually vulnerable, whether the security product they bought to

Speaker 2 prevent exploitation is actually working, right?

Speaker 2 So one of the great things about having a publicly available exploit for a recently disclosed vulnerability is you can make sure that all your mitigations, all your controls, all your detection are actually working the way they're supposed to.

Speaker 2 And everybody else did not want that.

Speaker 1 At the time, Microsoft's browser was Internet Explorer.

Speaker 1 And with the chip on his shoulder from dealing with Microsoft in the past, HD decided to see how many vulnerabilities he could find in Internet Explorer.

Speaker 2 Basically, we're myself, a couple of friends, we put together some browser fuzzers. We used the browser's own JavaScript engine to just find hundreds and hundreds of vulnerabilities.

Speaker 2 We tested every single ActiveX control across Windows and just found bugs in all of them at once.

Speaker 2 So we basically created this mass vulnerability generator and we're sitting on probably like six, 700 vulnerabilities at the time and the vendors were just not moving on it.

Speaker 1 He kept reporting bug after bug to Microsoft. But from his perspective, nothing was getting done.

Speaker 2 And so now, what do you do when you've told the vendor about a bunch of bugs and they didn't act on it and you have hundreds more and it got to the point that like we just gave up we said you know what we're gonna do entire month we're gonna drop node eight every single day for a month straight and we'll still have hundreds left over afterwards and it was that particular sequence and in that particular event that i think finally killed activex and internet explorer

Speaker 2 why why do you think that well after the 30 or 40th active x vulnerability reported them we're like hey guys we have two or 300 more we can keep we can go keep going all year at this point

Speaker 2 and it was a good indication that they realized there was no safe safe way to implement ActiveX control load and Internet Explorer.

Speaker 1 Microsoft was realizing the security in their products wasn't cutting it. They needed to do better, and they were working on that.

Speaker 1 In fact, what they started doing was offering jobs to people who were reporting bugs to them.

Speaker 2 So if you were someone who is previously reporting a bunch of vulnerabilities to Microsoft, all of a sudden you got a job offer instead. I mean, there's a...

Speaker 2 also the amazing security research group called Last Ages of Delirium out of Poland. And three of the four folks that were part of this group joined microsoft um during this time

Speaker 1 well did they contact you

Speaker 2 um we're we're friends i met them in um malaysia and i'd see them at conferences and stuff like that i definitely got a few offers from microsoft early on but you know i kind of pushed back with ridiculous terms saying you know no way in hell essentially um mostly because i felt like they didn't really have the best interest of the community at heart they definitely they would shut down anything i was working on and for the most part it was true folks who took a job at microsoft um after doing fully vulnerability research before, you never heard a peep out of them again.

Speaker 1 Can you imagine if that happened, if HD got hired by Microsoft? They might have tried to close down Metasploit altogether. And what a loss that would have been.

Speaker 1 Because Metasploit was starting to pick up some traction. And while it was hated by many, it was being used by many more.

Speaker 1 Pen testers all over were beginning to use it as one of their primary tools to test the security of a network.

Speaker 1 It was shaping up to be a vital and amazing tool as a pen tester because it made their job so much easier than before. As the need for pen testers rose, the need for better pen tester tools rose too.

Speaker 1 And of course, the whole time, Metasploit was free and open source, so the community could just look at the source code and verify there wasn't anything malicious getting installed on someone's computer once you hack into it.

Speaker 1 The security community was slowly adopting it and liking it more and more every day.

Speaker 1 Well, as time went on, Microsoft really did step up their game on handling bugs found by researchers.

Speaker 1 They were patching things much quicker and were learning that they cannot control the bugs that outside researchers discover. And that's kind of a hard thing, even for companies, to understand today.

Speaker 1 If someone finds a bug in your product, you can't control what that person does with that bug. You can try to offer a bug bounty reward to them, but that doesn't mean researchers will take it.

Speaker 1 They might sell it to someone else or publish it publicly for everyone to see. Software vendors cannot control what people do with the bugs they find.

Speaker 1 And people like HD, who was just publishing vulnerabilities all the time, were making that point crystal clear. Microsoft has an internal conference that's just for Microsoft employees.

Speaker 1 It's called Blue Hat. And at some point, they started inviting security researchers from outside Microsoft to come talk at it.

Speaker 1 HD knew one of the researchers who was giving a talk and was invited to come co-present at Blue Hat. So HD got to go to this exclusive Microsoft conference and present to their developers.

Speaker 1 I just imagine like

Speaker 1 your talk is just like,

Speaker 1 here are the 400 things wrong with Microsoft.

Speaker 2

Yeah, there's a lot of that. It was like, you know, one good example.

So back in, was it 2005 or so,

Speaker 2 I was on the flight over to Blue Hat and I was playing with a toolkit that I was calling like Karmenasploid at the time or Karma meets Metasploit.

Speaker 2 Karma was a way to convince wireless clients to join your fake access point and then immediately start talking to you and try to authenticate to you like you're a file share or printer.

Speaker 2 So, essentially, if you had your Wi-Fi card enabled, let's say on an airplane, and someone was running this tool on a different laptop in the same airplane, they would then join your fake access point, try to access company resources automatically, give you their password most times, and then provide a lot of exploitable scenarios where you can actually take over the machine.

Speaker 2 So, we thought it'd be fun to run this tool on the actual airplane as we're flying to Blue Hat.

Speaker 2 And lo and behold, we end up collecting a bunch of password hashes from Microsoft employees in the process.

Speaker 1 You little stinker.

Speaker 2 It was fun times.

Speaker 1 Where are are you on this whole responsible disclosure thing? Do you want to get this stuff fixed ASAP?

Speaker 1 Or are you more, like, where do you,

Speaker 1 what do you think you should do with a vulnerability if you find it?

Speaker 2 After going down that path a few hundred times, the fastest way to get a vulnerability fixed is to publish it on the internet that day.

Speaker 2 You know, whether that's responsible or not, it's effective.

Speaker 1

Well, he has a point. It's true.

If you find a bug and want it fixed as fast as possible, make it known to the world in the biggest biggest and loudest way, and it will get fixed fast.

Speaker 1 But even though that's the fastest path to getting a bug fixed, it's not the responsible way to do it because doing that exposes a lot of people who can't do anything to stop that attack.

Speaker 1 It means criminals can use it before it's fixed. And this puts a lot of people at risk, which means you're probably doing more damage than helping.

Speaker 1 It's better to privately tell the software maker and give them time to fix it. But then when they aren't fixing it and you've given them plenty of time,

Speaker 1 then they might need a little fire under them to get them moving on it. Sometimes to get a company motivated, you've got to give them a little bad PR.

Speaker 2 It definitely depends on the vulnerability.

Speaker 2 These days have been leaning towards like kind of a 98 disclosure policy where you tell the vendor about it for 45 days, then you tell somebody else about it as a dead man switch.

Speaker 2 And if the vendor sits on it and it leaks, the other person's going to publish it no matter what.

Speaker 2 I've been using that strategy by working with US CERT for the last few years, where whenever I publish a vulnerability to a vendor, they get 45 days of, you know, only them having access to it.

Speaker 2 And then 45 days later, it goes to US CERT, or sorry, CERT CC. And they're basically guaranteed to publish it after 45 days.

Speaker 2 So the great thing about that model is you're kind of splitting the responsibility.

Speaker 2 You're making sure that the vendor takes it seriously and gets the patch out of in time.

Speaker 2 But you're also not, you know.

Speaker 2 having to publish it directly in the internet.

Speaker 2 So having a third party like that really reduces the ability of the vendor to pressure any individual researcher from not disclosing because it's already in the hands of another

Speaker 2 party at that point.

Speaker 1 There are a few groups that have adopted this same model. Trend Micro has the zero-day initiative, and Google has Project Zero.

Speaker 1 Both of these groups look for vulnerabilities and report them to the vendor, and then give the vendor 90 days to fix it, and then they're going to publish it publicly.

Speaker 1 So the vendor knows if they get a bug report from any of these groups, they have to act quick and get it fixed before it becomes public because that would be a PR nightmare.

Speaker 1 And it's wild to see major tech firms like Google playing this sort of hardball game with software makers. But this has been working pretty well.

Speaker 1 It's also interesting to note that HP bought Trend Micro, and a few times the Zero Day Initiative has found vulnerabilities in HP products, which didn't get fixed in that 90-day window.

Speaker 1 And so the Zero Day Initiative published HP vulnerabilities publicly. It was wild and refreshing to see them even treat their parent company the same way as everyone else.

Speaker 2 Yeah, it's great. I mean, I think it's effective.

Speaker 2 Sometimes you have to, I mean, the folks I chatted with at HV about their like, yep, that's the only way that team's going to get the resource they need to fix the product is if we publish it at zero day.

Speaker 1 At some point, Metasploit got a new feature called Meterpreter.

Speaker 2 Meterpreter was the brainchild of Matthew Miller Escape. And, you know, a lot of other folks worked on it, but he was really the architect behind it.

Speaker 1

Meterpreter is a payload. Remember, the payload is the action you want to happen after your exploit opens the door for you.

But the Meterpreter payload is kind of like the ultimate payload.

Speaker 1 It lets you do so much on the target system that you just hacked into you can look at what processes are running you can upload a file to that system or download a file it helps you elevate your privileges or grab the hash file where the passwords are stored i mean think about that for a second let's say you use metasploit to get into a computer and with one command hash dump it knows exactly where the password file is on that computer and it just goes and grabs it and downloads it to your computer so you can just start cracking passwords locally if you want.

Speaker 1

You don't need to know where the password files are stored on that computer. Meterpreter knows that for you.

You just need to know the one command, hashtum, and you got them.

Speaker 1

But Meterpreter does so much more than this. It lets you turn the mic on and listen to anything the mic is picking up.

It lets you turn the webcam on and see what that computer can see.

Speaker 1 It lets you take screenshots of what the user is doing right now. It lets you install a key logger if you want to see what keys the user is pushing.

Speaker 1 Meterpreter is incredible, but with a payload like this, it makes a Metasploit Metasploit so much more dangerous.

Speaker 1 I mean, all these features can be easily abused by the wrong person and can cause lots of damage.

Speaker 2 On the vendor side, it was scary for them because instead of exploits being these really, you know, simple payloads that they would drop, they could easily detect. Now

Speaker 2 exploits could drop anything. They could drop

Speaker 2 TLS encrypted connect backs. They could drop basically mini malwares instead that are able to automatically dump password password hashes and communicate back over any protocol you want.

Speaker 2 So we made the payload side of the exploitation process incredibly more complicated and way more powerful.

Speaker 2 This is kind of one of those points where some of the features of Metasploit, especially around Meterpreter, start getting really close to the malware world.

Speaker 1

Right. And I think that's where I want to head.

But like, you're not just...

Speaker 1 doing a proof of concept of, okay, look, I can get into your machine and I, here's, you know, who am I or something, and what process ID I'm running as.

Speaker 1 You're building this tool. Meterpreter gives you full access to that computer, which allows you to screenshot, do keyboard, you know, sniffing, whatever.

Speaker 1 All these things that are a lot more like thumb in your eye kind of thing.

Speaker 1 And I don't know if that's taking it too far. Like, does it feel like that's what I'm,

Speaker 1 it's not just a proof of concept.

Speaker 1 It's a, we can, we can completely like destroy this machine if we wanted, which I guess you have to kind of prove that in order to show, you know, the veracity of this vulnerability, but it just, it's almost going too far for me.

Speaker 1 What do you think?

Speaker 2 Uh, well, one of my favorite things with Interpreter is we had a way to load the VNC desktop sharing service in memory as part of the payload itself. And we had it wired up in Metasploit.

Speaker 2 So you would literally run the Metasploit exploit and you'd be immediately get a desktop on your screen, be able to move the mouse cursor, be able to type on their keyboard.

Speaker 2 It was immediate remote GUI access to a machine over the exploit channel itself, which is just mind-blowing at the time for payloads because it didn't depend on RDP or anything like that.

Speaker 2

It didn't depend on the firewall being opened because they do a connect back to you and then proxies it. It was just an amazing delivery.

That specific payload.

Speaker 2 blew so many minds that it was really easy for us to show the impact of an exploit. If you're trying to show an executive after doing a pen test, hey, we got into your server.

Speaker 2 Here's a command prompt of us doing a directory listing. That's one thing.

Speaker 2 But if you're showing that you literally take over their server and you're moving the mouse on their desktop within two seconds of connected to the network, that is an entirely different level of impact that you can show.

Speaker 2 It also let us build a lot of other really complex, really interesting use cases where it really shows what the impact of the exploit is.

Speaker 2

It isn't just like, oh, you've got a bug and you didn't patch it. And now I've got a command chill.

It's like, no, no, I have all this access to your system, whatever it happens to be.

Speaker 1 Yeah, I guess that's kind of what drew me to Mass Play as well is like, oh my gosh, it's not just the exploit. It's what you do with the exploit after you get in.

Speaker 2 but as you were saying the um the meta interpreter started uh getting close to being its own malware explain what you mean by that a lot of the um malware payloads even today are written in c and they've got these kind of advanced uh communication channels and c2 contact mechanisms and all this kind of boilerplate stuff that they do like uh providing the ability to chain load payloads download more stuff talk to backends uh bounce between different backends uh we got maturpa to the point that it actually had the same capabilities as some of the more advanced malware that are out there.

Speaker 2 And that's when it started getting a little squiffy for me because it's like, we don't want to be in the malware business.

Speaker 2 Like, we're here to show the impact of exploits and let people test our systems and to generally, like, you know, demonstrate the security impact of a failed security control or missing patch.

Speaker 2 But we're not here to persistently infect machines. And Metropolita got very, very close to that line.

Speaker 2 The thing that really separated it from actual malware is the fact that it was always memory-based only. It was never on disk at all.

Speaker 1

This is a strange territory to be in. Metasploit is a tool that's sole job is to hack into computers.

Whether you have permission to do that or not, that's the purpose of it.

Speaker 1 But it seems to be the intent of the person using it that tells us whether Metasploit is malware or a useful tool.

Speaker 1 So the Metasploit team had to be very careful on how far they took this tool. Now, this is a multi-

Speaker 1 open source, you know, multi-developer project.

Speaker 1 Did you have some sort of manifesto that said, or a meeting that said, okay, guys, here's, we're going to, we're going to push this all the way goes, except no persistence.

Speaker 2 Like,

Speaker 1

was there a manifesto of like, like you just said, you know, you don't want to leave your customers weaker. This is a secure, this is a professional tool.

It's like

Speaker 1 something written out there.

Speaker 2 It was never like a written manifesto because it wasn't like a ethical boundary. It was just a practical boundary.

Speaker 2 Like you're not going to use Metasploit for a pen test if it at least garbage a load of your machine afterwards or backdoors it in a way that's difficult to fix.

Speaker 2 Some exploits require temporarily creating like a backdoor user account or otherwise creating something that would otherwise create more exposure.

Speaker 2 And we're always really careful to document what the after exploit scenario looks like. Okay, after you run this thing, you need to do this other thing.

Speaker 2 So we created these like post-cleanup modules that would remove the trace of whatever the thing was. But that was something that I always agonized over because I really hated.

Speaker 2 having to create any kind of like have to lower the security of the system as part of the exploitation process. I was like that was counterintuitive.

Speaker 2 That was kind of going against what we're trying to do in the first place.

Speaker 1

Yeah, I know. And maybe I'm not explaining it well, but it just seems like you're putting your thumb right in the customer's eye.

And then you're like, well, we don't want to hurt you. You know?

Speaker 2

Well, that's the thing. You're trying to be a professional adversary.

And so you have to have the most possible, you know, brutal, malicious.

Speaker 2 approach to the problem in a sense that you're going to use the same technique someone else would.

Speaker 2 But then you need to draw the line about where you leave the customer afterwards and what the actual impact of the attack is.

Speaker 1 Okay, so we heard HD has many adversaries, right? Cyber criminals don't like him publishing their weapons and making them ineffective.

Speaker 1 Old school hackers don't like that he's making hacking so easy that a script kitty can do some amazing stuff. And vendors don't like that he's publishing their bugs.

Speaker 1 He's getting hit on all sides by these people. But there's one more group that's also not happy about Metasploit.

Speaker 1 Law enforcement. There were crimes committed with Metasploit.

Speaker 2 Yeah, that's my first experience writing Windows shellcode. The first Windows shellcode ever published by Metasploit ended up in the blaster worm almost immediately afterwards.

Speaker 1 See what I mean? There was a massive worm that was using the information that he published to do dirty work out there.

Speaker 1 And I just read an article today that said in 2020, there were over 1,000 malware campaigns that used Metasploit.

Speaker 1 And so what happens in this situation when you're making tools that criminals are using? Well, let's go back and look at a few other cases. I did an episode on the Mariposa botnet.

Speaker 1 The people who launched this botnet all got arrested, but they weren't the ones who developed the botnet. The butterfly botnet was created by a guy named Acerdo.

Speaker 1 But this Acerdo guy, all he did was develop the tool and put it out there. He never used it to attack anyone, but he was arrested and sentenced to jail just for developing the tool.

Speaker 1

What the court proved was that he was knowingly giving it to criminals to commit crimes. Or let's look at Marcus Hutchins.

He developed malware, which became known as Kronos, but he only developed it.

Speaker 1 He never launched it on anyone. But it was because he was giving it to someone who did use it to go and attack banks is why Marcus was arrested by the FBI.

Speaker 1 In both of these cases, what it came down to was whether or not the software maker was knowingly giving these hacking tools to someone who had intent on breaking the law with it.

Speaker 1 But HD claims he has no responsibility with what people do with his tool.

Speaker 2 I don't know. If you bake a bunch of cookies and put them on a sheet in the street and say, free cookies, like, are you responsible if a criminal eats a cookie? I don't know.

Speaker 2

Like, I feel like it's different. It's open source.

It's community-based. It's an open domain.

Everyone's on the same playing field.

Speaker 2 I feel like it's one of those things where if you're only providing those exploits or those weapons to someone in the criminal community and charging for them, that's one thing.

Speaker 2 But if you're creating a project for the purpose of helping everyone else understand how things work and to test their own systems, and a bad actor happens to pick it up and use it too, that seems like something very different.

Speaker 1 But I get worried for HD because he takes Metasploit to hacker conferences and hacker meetups to demo it and teach it to other people there.

Speaker 1 And everyone knows there are criminals who attend these things. I mean, just sharing it with the hacker chat rooms that he was part of.

Speaker 1 Like, Frack, how could he have gone all this time without once seeing that the person that he just taught this to or gave it to was a known criminal?

Speaker 1 Did you have any lawyers helping you on this project?

Speaker 2 No, once in a while, I'd have to reach out for help, but it usually wasn't from a lawyer that

Speaker 2 hired myself, usually just people I knew that happened to be lawyers who give me advice on stuff.

Speaker 1 But that's why I'm asking about a lawyer is whether or not you had some sort of fine line on what the point of Metasploit was and maybe some of the language involved with the terms of use.

Speaker 1 Like maybe there was something there that said, you cannot use this for criminal behavior or something.

Speaker 1 Where was this to keep you out of trouble?

Speaker 1 What did you do to stay out of trouble in this sense?

Speaker 2 I mean, I think early on the solution was my spouse had a get out of jail fund, had a like lawyer fund sitting aside.

Speaker 2 So if I got dragged off in the middle of the night, she had cash that was not tied to my personal accounts or shared accounts to find a lawyer and give me bail money basically so that was the case for about six seven years where i was pretty concerned about getting arrested for almost anything i was working at the time because it was all pretty close to the line whether it's internet scanning whether it's the metasploid stuff um you know it really comes down to whether so you think you know a prosecutor is going to make a case whether you think they they think they can make a case like prosecutors don't want to lose a case so they're not going to bring um a charge against you unless they're very certain that they're going to win um that's why the conviction rates were so high.

Speaker 2 So it's one of those things where intent matters, but what really matters is whether the prosecutor really wants to go after you or not.

Speaker 2 And if you convince them that, you know, hey, I'm not actually a bad actor and I'm not doing this stuff and I'm not driving this economic activity that's related to criminals, then that's helpful.

Speaker 2

But that's one of the things I really don't like about U.S. law.

It's, you know, the CFAA doesn't care about intent, for example.

Speaker 2 There's nothing about our Computer Fraud and Abuse Act that cares whether you're doing it for good or not.

Speaker 2

And a lot of our laws are problematic like that. It isn't just like the standard section that's quoted.

It's also section like 1120. There's a couple other parts of the U.S.

Speaker 2 Criminal Code that are just really dangerous when they're taken out of context or

Speaker 2

used to make a case for something that really shouldn't have been prosecuted in the first place. So, unfortunately, like a lot of U.S.

prosecutions really just come down to

Speaker 2 whether someone wants to go after you or not. And all you can do is, you know, do your best to stay above the law when you can.

Speaker 2 And when the law is really vague, do your best to not be attempting target

Speaker 1 yeah but i'm i am surprised that when when i load up when i load up some software or even look at some you know how-tos and videos on how to hack there is a um

Speaker 1 a disclaimer at the beginning do not use this for illegitimate purposes don't do not break the law with this information and when i when i load metasploit it doesn't say for pen testing only, only use on systems you have permission to.

Speaker 1 And I'm wondering, why would you keep that off there?

Speaker 2 i don't think it ever occurred to us out of warning honestly like we figured if you're downloading medicable you know what you're getting into you know you're downloading a security tool to do security testing and we're not there to tell you you shouldn't you know um

Speaker 2 jaywalk or you shouldn't you know firebomb your neighbor's house like we assume people have reasonable reasons why they're using the software in the first place and we don't feel like we're enticing them to commit a crime because we're providing them a tool

Speaker 1 got it however in the real world you might be pressured because law enforcement says, look, man, we keep finding criminals that are using your tool. You need to do something more.

Speaker 1 You need to put a terms of use up. A lawyer might have, like, you might have had to get a lawyer to say, hey, what do we need to do so that we don't get in trouble?

Speaker 1

And I'm surprised none of that just hit you in the face. Like the law, like, so black hats are mad at you, vendors are mad at you, but the law wasn't mad at you.

I'm surprised.

Speaker 2 I mean, stuff came up for sure, but mostly was able to talk my way out of it one way or another.

Speaker 2 I think a lot of it is just the way to win in that space and to not go to jail was just to be as loud and as blatant and as above board as you possibly can.

Speaker 2 So, you know, doing a Metasploit talk at every conference, having you know, tens of thousands of Metasploit users early on, having 200 different developers involved with the project.

Speaker 2 The bigger, the wider, the more noisy we could make the project, the less likely someone was going to say, This is the tool for just criminals. We're going to go after it.

Speaker 1 You just have such a

Speaker 1 surprising, like

Speaker 1 an adventurous life.

Speaker 1 There's a big difference between your typical pen tester and HD Moore. The typical pen tester today learns how to use Metasploit, which is the tool that HD created.

Speaker 1 And HD is the one learning how the exploits work, writing the shellcode to make them work, and actively trying to find new exploits all the time.

Speaker 1 On top of that, he's fielding a non-stop barrage of attacks himself from creating the tool, so he's well versed at defending and attacking systems.

Speaker 1 The experience he has in this space is almost unparalleled. But it was because of how much passion he has about security that got him to this point.

Speaker 1 And I just want to say to any up-and-coming pen testers out there, getting your hands on working exploits and contributing to open source projects is a fantastic way to become fluent in this field.

Speaker 1 There are a ton of open source hacker tools out there on GitHub, and it's a great experience to download the source code and see how they work and try to improve upon them.

Speaker 1 And even if you're just a beginner, there's probably something you can do to help, whether it's writing better documentation or improving the help menu.