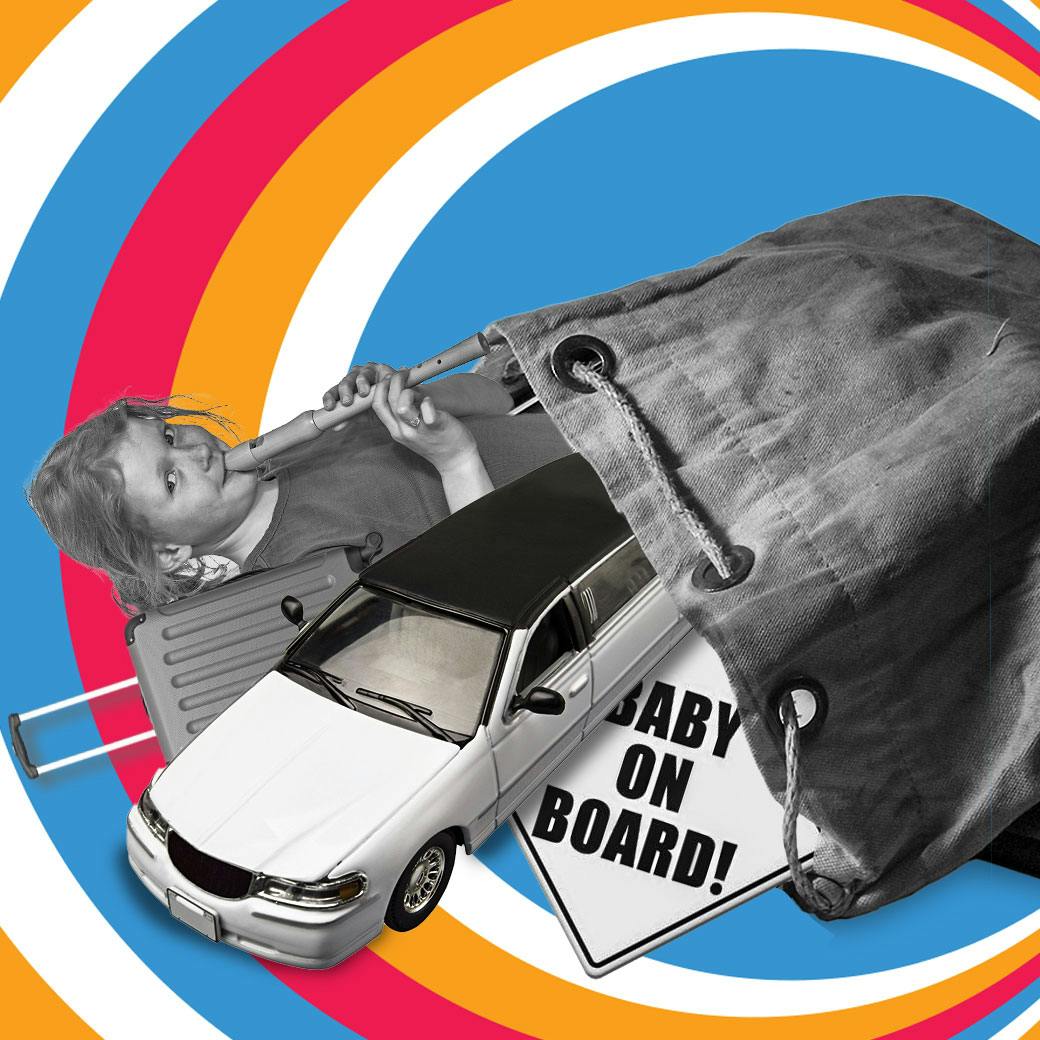

Mailbag: The Recorder, Limos, and “Baby on Board” Signs

Decoder Ring is produced by Willa Paskin and Katie Shepherd. This episode was also produced by Rosemary Belson. Derek John is executive producer. Joel Meyer is senior editor/producer. Merritt Jacob is our senior technical director.

Thank you to every listener who has submitted a suggestion for an episode. We truly appreciate your ideas. We read them all, even if we don’t always respond. Thanks for being a listener and for thinking creatively about this show.

If you haven’t yet, please subscribe and rate our feed in Apple Podcasts or wherever you get your podcasts. And even better, tell your friends.

If you’re a fan of the show, we’d love for you to sign up for Slate Plus. Members get to listen to Decoder Ring without any ads. Their support is also crucial to our work. So please go to Slate.com/decoderplus to join Slate Plus today.

Learn more about your ad choices. Visit megaphone.fm/adchoices

Press play and read along

Transcript

Speaker 1 That's the sound of the fully electric Audi Q6 e-tron and the quiet confidence of ultra-smooth handling. The elevated interior reminds you this is more than an EV.

Speaker 1 This is electric performance redefined.

Speaker 2 Liz Stevenson grew up in a suburb outside of Boston, and at her elementary school, you always did this one thing come third grade.

Speaker 4 You always learned the recorder, You know, this recorder.

Speaker 2 I learned to play the recorder in fourth grade, and learning to do so is a common elementary school experience, even if it is not always a mellifluous one.

Speaker 3 Instead of going to the regular music classroom, we would do this in what was called the multi-purpose room, this big open room where they would put in like risers.

Speaker 3 I do remember thinking we sound bad.

Speaker 2 If you played the recorder or know someone who did, you can probably imagine the sounds emanating from the multi-purpose room.

Speaker 3 All I remember learning is hot cross buns and like Camptown races.

Speaker 3 I think the only one that I mastered was hot cross buns.

Speaker 2 I think it's fair to say that Liz's childhood experience did not leave her with any lasting knowledge of the recorder as a musical instrument.

Speaker 3 I don't even remember how many holes there are.

Speaker 2 But it did leave her with questions.

Speaker 3 What's the history of the recorder? Like, when was it invented? Who invented it? Why? How was it used in the past? And then, also, did it become popular at a certain era? And then, also,

Speaker 3 are there any people who are like talented at the recorder who play the recorder and show off how good they are at the recorder?

Speaker 2

So, I'm going to tell you this one thing. Yeah.

Which is that Vivaldi and Bach and Handal

Speaker 2 all wrote recorder music.

Speaker 6 Oh, wow.

Speaker 2

This is Decodering. I'm Will of Haskin.

We get a lot of fantastic emails from our listeners suggesting ideas for the show. We feel extremely grateful for each and every one.

Speaker 2 And in this episode, we're going to dive into five of them. First, we're going to continue with the history of the recorder, which surprisingly involves Henry VIII and the Nazis.

Speaker 2 We'll also be looking at the rise and fall of the stretch limo, the incredible versatility of the word like, the meaning of the baby on board sign, and why on earth it took so long to develop luggage with wheels.

Speaker 2 So today on Decodering, we're rifling through our mailbags. Thanks to you.

Speaker 2 I get so many headaches every month.

Speaker 7 It could be chronic migraine, 15 or more headache days a month, each lasting four hours or more.

Speaker 8

Botox, autobotulinum toxin A, prevents headaches in adults with chronic migraine. It's not for those who have 14 or fewer headache days a month.

Prescription Botox Botox is injected by your doctor.

Speaker 8 Effects of Botox may spread hours to weeks after injection, causing serious symptoms.

Speaker 8 Alert your doctor right away as difficulty swallowing, speaking, breathing, eye problems, or muscle weakness can be signs of a life-threatening condition.

Speaker 8 Patients with these conditions before injection are at highest risk. Side effects may include allergic reactions, neck and injection, side pain, fatigue, and headache.

Speaker 8 Allergic reactions can include rash, welts, asthma symptoms, and dizziness. Don't receive Botox if there's a skin infection.

Speaker 8 Tell your doctor your medical history, muscle or nerve conditions, including ALS Lou Gehrig's disease, myasthenia gravis or or Lambert Eaton syndrome, and medications including botulinum toxins, as these may increase the risk of serious side effects.

Speaker 7 Why wait? Ask your doctor. Visit BotoxChronicMigraine.com or call 1-800-44-Botox to learn more.

Speaker 2 So we're going to pick up where we left off with Liz's questions about the recorder. And to answer them, I reached out to Robert Ehrlich.

Speaker 9 I am a professional recorder player.

Speaker 2 So right off the bat, that's one answer. There are professional recorder players.

Speaker 2 Robert also teaches at the Leipzig Conservatory in Germany and is the co-author of a definitive history of the recorder.

Speaker 2 He was first introduced to the instrument himself when he was in elementary school in Belfast.

Speaker 9 I think we all know what that sounds like, and that wasn't the reason that I got into playing the recorder.

Speaker 2 Instead, he re-encountered the instrument as a teen.

Speaker 9 My dad gave me an album by Frantz Brigham. Brigham was a Dutch recorder player,

Speaker 9 Just masterly playing. It was a Favalde concerto, and it's just so exciting to hear this instrument played in a way that I'd never imagined it could be.

Speaker 2

The recorder actually seemed kind of rebellious to Robert. It wasn't an instrument that people took that seriously.

It wasn't the violin or the piano or the bassoon. And he liked that about it.

Speaker 2 It was like an underdog. So he learned how to play it, like,

Speaker 2 really play it.

Speaker 2 that's Robert playing and learning how to play he also became very interested in its history it turns out that for most of its existence the recorder was not for children so the golden age of the recorder

Speaker 9 was really the 16th century so if you think of King Henry VIII of England and that was the guy with all of the wives. Quite early in his reign, he employed a professional recorder ensemble.

Speaker 2 Henry VIII liked the instrument so much, he wrote a recorder song himself.

Speaker 2 At the time, the instrument was still fairly simple.

Speaker 9

So we're talking about a very plain tube of wood. It's cylindrical.

It basically looks like an extended toilet roll with holes down the end.

Speaker 2 But it was prestigious, and its looks eventually caught up with it.

Speaker 9

We're talking about a high stasis instrument. It was certainly an extremely expensive instrument.

And then in the Baroque era, so now we're talking the 17th, 18th centuries,

Speaker 9 it develops into a much more ornamental instrument. It starts looking very fancy, starts being made of ivory and with gold mounts and carved.

Speaker 9 It's a much more complicated inner bore, and that means the range gets extended to two and a half to three octaves.

Speaker 9 And that's the instrument that composers like Bach and Handel wrote their music for and for Valdi.

Speaker 2 But something was happening at the same time that was going to undo the recorder.

Speaker 9 The musical world is getting professionalized, and we start having the phenomenon that music moves out of the home, the court, the chapel, into the concert hall, and the rooms just get bigger.

Speaker 2 And in those big rooms for 2,000 people, you could not hear a number of theretofore esteemed instruments, including the lute, the harpsichord, the violeta de gamba, and yes, the recorder.

Speaker 2 Replacing them were the violin and the piano and the trumpet and all the instruments we still associate with symphony orchestras.

Speaker 2 By 1750, recorders had gone so out of fashion that people would forget how to make them.

Speaker 2 It wasn't until the early 20th century, amid a growing interest in early music, music from the medieval Renaissance and Baroque periods, that anyone tried again.

Speaker 2 A string instrument maker in Britain figured out how to make a recorder by looking at old surviving examples.

Speaker 2 Still, the recorder might be like the lute or the violeta de gamba if a german businessman named Peter Harlan hadn't noticed the redeveloped recorder and sensed an opportunity.

Speaker 9 Harlan had a wonderful commercial idea, which was,

Speaker 9 if I could make these really cheaply, I could sell Godzillions of these things.

Speaker 2 This was during the Weimar era after World War I when Germany was extremely poor.

Speaker 9 And so you've heard of the Volkswagen, right?

Speaker 9 And so Peter Haaland had this great idea of the Volksblockflerte, which just means people's recorder.

Speaker 9 And they were dirt cheap, they weren't good to look at, and they sounded terrible. But if you had no money to buy any other kind of instrument, it was kind of like a ticket back to musical experience.

Speaker 2 And so 250 years after it had disappeared, the recorder caught on again.

Speaker 9 Unfortunately, at the time, a lot of other things were catching on. The Nazis rose to power, and the Hitler Youth Movement kind of adopted the recorder as its instrument.

Speaker 2 It had been forgotten for so long, the Nazis saw it as an instrument with no past, one they could use for their own purposes.

Speaker 9 Right the way through its history, from 1500, 1600, 1700, it was essentially a male-gendered, luxury instrument for people of high society.

Speaker 9 And in the modern revival, it became re-gendered as a female instrument to be played by groups of girls and essentially to be used for propaganda purposes.

Speaker 9 So when we get up to the opening of the Berlin Olympic Games in 1936, there was a recorder orchestra at the opening ceremony in the Olympic stadium, microphones, loudspeakers, and there they were playing unspeakable Nazi drivel.

Speaker 2 You'd think this might have been it for the recorder.

Speaker 9 So what happened after the war was that a lot of things that had essentially been Nazi inventions, like the Autobahn, the freeway, and the Volkswagen, the Beetle, became ubiquitous in the developed world.

Speaker 2 Germans who had learned the recorder before and during the rise of the Nazis, including many German Jews, began spreading it to places like America, Israel, and Britain.

Speaker 2 It really is a useful teaching instrument because it's cheap and indestructible. And though it's hard to make it sound good, it's simple to make it sound at all.

Speaker 9 So the recorder got taken over all over the place.

Speaker 9 For professional players such as myself, that's our greatest curse and our greatest privilege. Everybody knows that instrument.

Speaker 9 Many people have had personal experience of it, so it's kind of accessible. The problem is, it's become a low-status instrument.

Speaker 9 If you just think, what's the first thing you think of if you see a violin? Well, you think, oh, high-status, classical music. With the recorder, you don't have those associations

Speaker 9 until you've heard somebody playing it well,

Speaker 9 and then it starts growing.

Speaker 4 We'll be right back.

Speaker 14 Combined with balanced energy, perfectly flavored with zero artificial sweeteners. Introducing Liquid Ivy's new energy multiplier sugar-free.

Speaker 14 Unlike other energy drinks, you know, the ones that make you feel like you're glitching, it's made with natural caffeine and electrolytes. So you get the boost without the burnout.

Speaker 14 Liquid IV's new energy multiplier sugar-free hydrating energy.

Speaker 2 Tap the banner to learn more.

Speaker 17 This is a Bose moment. You're 10 boring blocks from home until the beat drops in Bose clarity.

Speaker 15 And the baseline transforms boring into maybe the best part of your day.

Speaker 17

Your life deserves music. Your music deserves Bose.

Shop Bose.com/slash Spotify.

Speaker 2 Our next question comes from Whitney Alexander, who grew up in Houston, but now lives in Brooklyn.

Speaker 19 I was curious why there seemed to be so many stretch limos in New York City in the 80s and 90s, at least according to many of the films that I watched as a child.

Speaker 1 Wow.

Speaker 1 Is this your car?

Speaker 2 Whitney's talking about movies like Wall Street, Working Girl, Arthur, and Big.

Speaker 15 Well, it's a company's car.

Speaker 1 Oh, this is the coolest thing I've ever seen!

Speaker 19 All of these movies made it appear as though the streets of New York City were flooded with limousines.

Speaker 2 Was that really the case?

Speaker 19 And

Speaker 16 what happened to them all?

Speaker 19 Because I actually tried to rent a stretch limo about two years ago for a party and there were none to be found. I'd just like to understand a little bit more about the limo boom of the 80s and 90s.

Speaker 19 Was it fact, fiction?

Speaker 6 I mean, at one point, we were up to like 20, 25 stretch limousines.

Speaker 2 Robert Alexander, no relation to Whitney, is the president of the National Limousine Association and the CEO of RMA Worldwide, a corporate transportation company he founded in the late 1980s when the limo boom was definitely a fact.

Speaker 6 And it was great because we were doing, you know, with funerals and weddings during the day, and then we would do nights on the town, or we would do executives going to and from the airport or to meetings.

Speaker 2 If you think of a limo as a chauffeured vehicle that gives its passengers privacy, you can trace it back centuries to, say, the stagecoach.

Speaker 2 But the first stretched-out automobile appeared in the late 1920s. By the 1940s, companies like Lincoln and Cadillac were making stretches.

Speaker 2 But it was in the 70s and really in the 80s that they hit their peak popularity and usage.

Speaker 2 Thanks to the famous ethos of that era.

Speaker 20 Greed,

Speaker 9 for lack of a better word, is good.

Speaker 2 That's Michael Douglas playing the business mogul Gordon Gecko in the movie Wall Street. And as Whitney noticed when she was a kid, in that movie, Gordon Gecko goes everywhere in a stretch limo.

Speaker 2 He wants everyone to see him in this big, flashy car. And that's because, even more than the limo, what was in the 1980s 1980s was ostentatiously flaunting one's wealth.

Speaker 2 But how rich people are supposed to perform their wealth is as subject to trends as anything else.

Speaker 6 It wasn't like overnight someone flipped the switch and the limousine became,

Speaker 6 is Reef Gauche the right word?

Speaker 6 It was a slow, slow thing.

Speaker 2 But gauche is what the stretch limo has become.

Speaker 2 The president may still drive around in an armor-plated version, but they are otherwise a signifier of cool to people who don't seem to know better, like the overgrown kid in Big or Kevin McAllister, the character Macaulay Culkin plays in Home Alone 2.

Speaker 2 The decline in the limo's status has been very tied up with financial crises, none more so than the financial crash of 2008 and Occupy Wall Street.

Speaker 6 If today you saw a CEO getting out of a stretched limo, you'd be like, wait a minute, what are they they doing here?

Speaker 6 What are they spending money on?

Speaker 2 The 1% don't want to be seen as Gordon geckos anymore, even if they are.

Speaker 6 So if you were going to go to downtown Manhattan today, the likelihood that you'd see a stretch limousine is very, very slim. Back in the day,

Speaker 6 like on a Friday night or something, they were everywhere.

Speaker 2 Now, stealth wealth and quiet luxury are in. And stealth wealth has a car of choice.

Speaker 6 The stretch limousine hasn't really died.

Speaker 6 It's morphed and changed. And so what it morphed into was an SUV, like an escalator, a suburban, or a navigator.

Speaker 2 Robert says this is the car all of his corporate clients use and entertainers too. And this is also the car you now see rich people using in movies and TV shows like Succession.

Speaker 2 There are SUV stretch limos, but those two have fallen out of fashion amid safety concerns. In 2018, one crashed in upstate New York, killing all 17 passengers.

Speaker 2 Meanwhile, the party function of the stretch has been taken over by another kind of vehicle, the sprinter van, otherwise known as the party bus.

Speaker 6 Which is like a limo on the inside, but they see 10, 12 people. You don't have to duck down to get into the cars.

Speaker 2 You can trick it out in all sorts of ways, but like the SUV, it still looks pretty nondescript from the outside. And these two stealthier vehicles have almost entirely replaced the limo.

Speaker 2 Robert only has two left in his fleet, which he uses for funerals and proms, and he doesn't see that they have much of a future.

Speaker 6 There's a very, very slim, like one in 100 chance I would be buying a new stretch horse in anytime soon.

Speaker 2 Our next question is about like a word I really like.

Speaker 22 Hi, I'm Owen, and I live in Los Angeles, California with a family of five.

Speaker 22 I'm just wondering, just why do we dislike so much and why do we do it in so much different ways?

Speaker 15 But it's like when I had this garden party for my father's birthday, right? I said RSVP because it was a sit-down dinner. But people came that like did not RSVP.

Speaker 17 So I was like totally bugging.

Speaker 22 It just feels weird, frankly, how much reason. Like, it's truly just like, I mean, I'm saying so much right now

Speaker 2 as a fellow devotee of like I really appreciated Owen's question and I loved talking to our next expert Alexandra Darcy who is a professor of linguistics at the University of Victoria in British Columbia Canada what's so amazing about like is that it's so complex you know if it's a noun or a verb we don't even we don't bat an eye but as soon as you get some of what people are convinced are new forms of like,

Speaker 18 which they can't ascribe in any clear way of function to, they just assume that they're meaningless and you can throw them in wherever you like. And they also assume that they're all the same.

Speaker 18 And they're not.

Speaker 18 They're not any of those things.

Speaker 2 What is the narrative people think about where like comes from?

Speaker 18 The story is that like came from the Valley Girls and that's why it has such a bad rap.

Speaker 17 I know, but we've been going together so long now. Like, I'm beginning to think I'm a piece of furniture set like an old chair.

Speaker 18 And I believed that narrative for some time myself.

Speaker 18 And then you start looking at historical records, and you realize this had nothing to do with the Valley Girls in terms of origin.

Speaker 18 There are court records from London, England, from the 18th century, that has like in it, the like that we don't like.

Speaker 18 So it has become more frequent since then, but that's what language changes do anyway, right? Like when something new is happening, moves really, really, really slow for the longest time.

Speaker 18

And then it starts to take off. And when it takes off, it takes off fast.

And that's when we start to notice it.

Speaker 18 And we never like it.

Speaker 2 Okay, so tell me about the likes we don't like.

Speaker 18

There's a like that goes between sentences. So you could say something along the lines of, I'd never known anybody who had died.

I had no experience with death.

Speaker 18 Like the first person I knew was my grandma.

Speaker 18

People don't like that one, but that is 300 years old. It's an overt marker that says these two things are connected in some way.

So I think of those ones as road signs.

Speaker 18 They're these friendly cooperative tools that sort of say like, okay, I'm going this way now.

Speaker 2 What is another example of a like we don't like?

Speaker 18 There's the like that shows up inside sentences. I was like jumping up and down or she's like really nice.

Speaker 18 So it too has a job, but what it's doing is it's saying things like, this is what I need you to pay attention to. So they were jumping up and down is one thing.

Speaker 18

They were like jumping up and down is quite another. It's relevant that they were jumping up and down.

You're supposed to feel it.

Speaker 2 Are there any other likes that we don't like?

Speaker 18 Those are the main baddies, but there's also the like that shows up in direct quotation. So when we're recreating speech or thought or action or gesture.

Speaker 18 And so, you know, I can say, oh, and I was like, this is super fun, where I'm quoting my own thought process. We don't like that one either.

Speaker 18 And yet, really, it is the best thing to have happened to English speakers in terms of storytelling.

Speaker 2 I mean, why is it so good for storytelling?

Speaker 18 Oh, it's amazing for storytelling. Because if you go back 100 years, it was mostly say.

Speaker 18 Say Say can only do speech. And once in a while, you can make it do thought if you say, I said to myself,

Speaker 4 right?

Speaker 18 So it's very, very constrained. People rarely, rarely up until those, you know, born in the 1950s, rarely told stories that encapsulated an inner thought process in the same way.

Speaker 18 So two things have happened, right? The first thing is that we started changing the way that we report stories when we're talking to our friends

Speaker 18 you see that there's this increase from hardly ever reporting inner states to inner state reporting becoming more and more frequent we actually needed something really versatile so like as a verb of quotation itself just emerges in response to this gap now when you listen to stories We're telling all kinds of stuff.

Speaker 18 We're repeating gesture. We're repeating sound effect.

Speaker 18 we're creating hypothetical situations, right? So I have recordings of stories that in the real world happened in the blink of an eye. So externally there was no story,

Speaker 18

but the speaker has this whole narrative about what happened, right? So I saw him come in and I was like, oh my God, I know that guy. And I looked at him again.

I was like, wait, is he?

Speaker 18

And then I was like, oh my God. I was like, oh my God.

I was like, that's so-and-so's ex-boyfriend. I was like, oh my God, I hope he doesn't see me.

Speaker 18 And it's a fantastic story, but it could not have been told that way

Speaker 18 until you had this form.

Speaker 18 So it's actually this incredible resource that has, in a sense, kind of exploded the possibilities for us in terms of. the types of stories that we can tell and the way in which we can tell them.

Speaker 2 I also noticed when you're talking, it's funny, like it seems as if you have thought about places you can't use like for clarity. Like you did it a couple times.

Speaker 2 I was like, oh, she's not using like because it would be confusing.

Speaker 18

I'm an Uber liker. I love like.

It's so useful. It's so helpful.

When I'm being very informal, I'm likeful. Like is everywhere.

But when I lecture.

Speaker 18 or do something like this, I try to use it less because

Speaker 18 I understand that there's an audience that doesn't like it. And it's important to me that the message comes across in a way that people are able to hear what I'm saying and not be

Speaker 18 distracted by me using the thing that they don't like and don't respect, and therefore will be predisposed to not like what I'm saying.

Speaker 18 You know, I have students all the time. So my dad bans it, my mom bans it, my nana bans it.

Speaker 18 And like, my response is always, you go back and you tell them that every time you use a like, you are saying in your heart, I love you, I trust you, I am comfortable in this space.

Speaker 2 Our next question comes from Debbie Byrne in Oakland, California.

Speaker 24 I'm wondering about the baby on board placards that are in the rear windows of many people's cars.

Speaker 24 I kind of remember when those first started appearing, and I always wondered what was the thought behind those signs.

Speaker 24 Like, of course, no one wants to crash into a car with a baby riding in it, but I also don't want to crash into a car with a six-year-old riding in it, or a 16-year-old riding in it, or even a 60-year-old riding in it.

Speaker 24 Who thought that up? Why are they so popular? And how come they're still around in 2023?

Speaker 2 To answer Debbie's question, I spoke with Caitlin Gibson, a feature writer for The Washington Post.

Speaker 2 She'd been noticing the baby on board signs for years, but she only wrote an article about them after a life change.

Speaker 16 We had our first daughter in 2018

Speaker 16 and experienced firsthand what it was like to put a completely fragile little newborn in the backseat of the car and drive her in the Washington, D.C.

Speaker 16 metropolitan area around the drivers who are here and

Speaker 16 started thinking a little bit more about what the sign actually might mean.

Speaker 2 The signs were co-created by a man who had a similar experience. In the early 1980s, Michael Lerner had to drive his 18-month-old nephew home from a family gathering in Boston.

Speaker 16 It was very stressful for him. He felt like people were driving really erratically and he was just very aware of this little kid in the back seat.

Speaker 2 About a week after the experience, a business associate got in touch with Lerner. He knew about these two sisters who had an idea they wanted to sell.

Speaker 16 And their idea was this triangular little safety sticker that said baby aboard.

Speaker 2 The pitch resonated with him because of his recent experience with his nephew. So he bought the idea, finessed the words, and launched a company called Safety First.

Speaker 16 And so by 1984, they were starting to produce these stickers. And he was saying that, you know, September of that year, they sold like 10,000 of them.

Speaker 16 And by the following June, they were getting orders for half a million a month.

Speaker 2 And as the 80s wore on, they kept selling, becoming completely ubiquitous.

Speaker 25 And let's not forget the three most puke-inducing words that man has yet thought of.

Speaker 25 Baby unborn.

Speaker 2 They drew the ire of the comedian George Carlin.

Speaker 25 You know what these morons are actually telling us, don't you? I know you figured this out.

Speaker 25 They're actually saying to us, we know you're a shitty driver most of the time, but because our child is nearby, we expect you to straighten up for a little while.

Speaker 2 And Homer Simpson and his barbershop quartet sang about them on The Simpsons.

Speaker 11 Baby unborn,

Speaker 11 how I've adored

Speaker 11 that sign on my

Speaker 2 Michael Lerner would go on to sell the company, but there has remained a consistent, if less feverish demand for his product.

Speaker 2 You can still see them on people's cars and in other countries and in other languages, and you can also see ones riffing on the original.

Speaker 16 I guess the new ones that are like just in the last couple of years are like the baby up in this bitch or like burrito on board, golden retriever on board.

Speaker 2 But even more than their longevity, the thing Caitlin found most fascinating about the baby on board signs was just how many different opinions they engendered.

Speaker 2 She started every interview she did for her piece by asking the subjects what they made of these signs when they saw them on the road. And she got so many divergent, even contradictory responses.

Speaker 16 There's just no universal interpretation of it.

Speaker 2 There were the people who thought it was basically like a status update.

Speaker 16 You know, like it was just people kind of announcing that they had reproduced.

Speaker 2 Others who thought it was a courtesy to let people know they might be driving cautiously.

Speaker 16 Almost kind of like an apology or an explanation. Like, I might, you know, not gun it if there's like a brief opening in traffic.

Speaker 2 But others still thought it meant the driver might be reckless.

Speaker 16

They felt like it was a warning. Like, I might be really distracted and do something completely nuts because there's a shrieking baby in the back seat.

So that really struck me.

Speaker 16 I'm like, wow, those are opposite messages.

Speaker 4 Like, uh-oh.

Speaker 2 There were the people who wanted it to alert first responders and others who would get annoyed when they realized there wasn't actually a baby on board.

Speaker 16 And then it was also kind of funny hearing from kids who are older who are like, well, I'm 11. Can you drive safely around me too? Or do I not count anymore that I'm 11?

Speaker 2 This is what seems so weird about the baby on board signs to our listener, Debbie, and also to George Carlin, the people with burrito on board signs, and frankly, me too.

Speaker 2 A baby is not more precious than an 11-year-old or a 16-year-old or a 60-year-old.

Speaker 2 And Caitlin agrees, but she thinks it's notable that the sci seems to especially resonate with brand spanking new parents, people driving home from the hospital who are not in the most logical frame of mind and who have just been made personally responsible, not for any other human life, but just one baby in particular.

Speaker 16 A guy that I spoke to for this story, he never really felt like he understood them until he had his first kid and he was driving this baby home from the hospital.

Speaker 16 When he had his baby, he suddenly started seeing them as just these messages of just fear.

Speaker 16 Like these are just scared parents who have suddenly realized in the way that you do when you bring new life into our incredibly turbulent and unpredictable and uncontrollable world that you have very little control over what you do, what happens to them.

Speaker 16 And that is really frightening.

Speaker 2 Basically, they're hail Marys, physicalized tokens of magical thinking, amulets, talismans.

Speaker 16 People like put like the patron saint of travel on their dashboard. This is not really that different.

Speaker 2 They're not communicating anything except, you know, a desire to control your panic.

Speaker 16 Some people really want you to know that they ran a marathon, and some people really want you to know that they love vacationing in the outer banks, and some people want you to know that they're just feeling kind of freaked out.

Speaker 16 And that's what I think when I see it now: that that is a driver who feels frightened, or vulnerable, or worried.

Speaker 2 More questions when we return.

Speaker 21 This podcast is supported by Progressive, a leader in RV Insurance. RVs are for sharing adventures with family, friends, and even your pets.

Speaker 21 So if you bring your cats and dogs along for the ride, you'll want Progressive RV Insurance.

Speaker 21 They protect your cats and dogs like family by offering up to $1,000 in optional coverage for vet bills in case of an RV accident, making it a great companion for the responsible pet owner who loves to travel.

Speaker 21 See Progressive's other benefits and more when you quote RVinsurance at progressive.com today.

Speaker 10 Progressive Casualty Insurance Company and affiliates pet injuries and additional coverage and subject to policy terms.

Speaker 12 At blinds.com, it's not just about window treatments. It's about you, your style, your space, your way.

Speaker 12 Whether you DIY or want the pros to handle it all, you'll have the confidence of knowing it's done right.

Speaker 12 From free expert design help to our 100% satisfaction guarantee, everything we do is made to fit your life and your windows. Because at blinds.com, the only thing we treat better than windows is you.

Speaker 12 Visit blinds.com now for up to 50% off with minimum purchase plus a professional measure at no cost.

Speaker 10 Rules and restrictions apply.

Speaker 2 Our final question comes from Arnaud, who lives in Northern California.

Speaker 13 So, a couple decades ago, I started noticing in airports that all luggage, suitcases, carry-ons, all luggage suddenly had four wheels. And it got me wondering what happened? Why wasn't this a thing

Speaker 4 long before?

Speaker 13 It seems like such a simple

Speaker 13 device. Did a patent expire?

Speaker 13 And, you know, how did it become the obvious standard?

Speaker 2

So as early as the 1940s, you can find advertisements for products that combine the wheel and the suitcase. Called portable porters.

They were wheeled devices that could be strapped onto luggage.

Speaker 2 But as the Australian comedian Jim Jim Jeffries explains, it would be another 25 years before somebody thought to put wheels on a suitcase permanently.

Speaker 26 1971 was the first time the Patent Office got a patent for a suitcase with wheels on it. 1971 was the first time anyone on this planet thought

Speaker 26 to put wheels on a suitcase.

Speaker 26 To put that in context,

Speaker 26 we went to the moon in the 60s.

Speaker 2 The breakthrough is widely credited to Bernard Sadout, who supposedly was going through an airport on a family vacation and spotted an airport worker wheeling around a piece of heavy machinery and thought it might work on the bags he was lugging around himself.

Speaker 2 When he got home, he slapped four wheels from another piece of furniture on his luggage, attached a strap, and the first very wobbly iteration of the rolling suitcase was born.

Speaker 2 But not everyone was moved by the idea. Part of the reason for this was that carrying a suitcase was seen as manly.

Speaker 2 Men were supposed to carry their own luggage, and it was assumed that most women were traveling with men who would carry their luggage too.

Speaker 2 It wasn't until the mid-1980s that another man who had to constantly schlep his own luggage through airport terminals revisited the idea.

Speaker 2 An airline pilot named Robert Plath turned his suitcase upright, gave it a handle, and wheels. He called his new design the rollerboard and started a company called Travel Pro to sell them.

Speaker 2 This time, the idea caught on.

Speaker 2 Rolling luggage now makes up a large part of the $152 billion American luggage market, and the bags are the preferred luggage of people like George Clooney's constantly traveling character in up in the air who just want to save some time.

Speaker 20 You know how much time you lose by checking in?

Speaker 2 I don't know, five, ten minutes.

Speaker 20

35 minutes a flight. I travel 270 days a year.

That's 157 hours. That makes seven days.

You willing to throw away an entire week on that?

Speaker 2 Rolling luggage is an obvious improvement over non-rolling luggage, but there have been other factors contributing to wield bags' ubiquity, namely the ever-mounting hassles of airline travel.

Speaker 2 Checking fees, canceled and delayed flights and connections, the near certainty that something will go wrong have all encouraged us to forego checking our bags in order to keep them close.

Speaker 2 And once you're lugging your own bag through the terminal instead of checking it, well, damn, it really needs some wheels.

Speaker 2 But I must confess that every single time I have to wedge my rollerbag into a bathroom stall, I think about how roller bags come with their own hassles.

Speaker 2 Not only do you have to wheel them everywhere, they have surely added to the thunderdome tension of onboarding when passengers seem so freaked out there might not be overhead room left for their bag and that it will have to get gate checked.

Speaker 2 In fact, some of the most pleasant or relatively pleasant airplane experiences I've had in recent years come when, already having to check car seats, I've checked my wheeled bags entirely.

Speaker 2 Because you know what's even easier than pushing a rollerbag?

Speaker 2 Not pushing any bag at all. I wanted to run the idea that rollerbags have alleviated and contributed to the nightmare that is air travel on someone who would know.

Speaker 27 My name is Nicholas, and I work for an airline in the United States.

Speaker 2 Do you find people and their luggage a stressful part of your job?

Speaker 27 Yes, yes, oh my gosh, yes.

Speaker 27 I actually made an announcement while I was watching People Board the other day, where I quite literally told people,

Speaker 27 My biggest pet peeve is that you cannot figure out how to stow your luggage.

Speaker 27 And I got some dirty looks, and I don't care.

Speaker 2 Do you see people being stressed out about their bags?

Speaker 27

Yes. Oh my gosh.

It has to be directly over their row. Pro tip for your listeners.

Don't put it over your extreme row. Put it ahead of you on the opposite side so you can see it.

Speaker 2 Like so much about modern life, the rollerbag is a convenience that solved a lot of problems. while creating a few new ones.

Speaker 2 There's a ripple effect to every innovation, even ones, come on, as obvious as putting wheels on a suitcase.

Speaker 27 It's entirely dumb that we didn't have rolling suitcases 35 years ago.

Speaker 2

This is Decodering. I'm Willa Paskin.

If you have any cultural mysteries you want us to decode, please email us at decodering at slate.com.

Speaker 2 I just want to reiterate what I said at the top, we are so appreciative and grateful for every suggestion that we get and we see them all, even if we don't always respond.

Speaker 2

Please also don't feel slighted if we haven't taken your suggestion on. Some topics are just too big to dive into in one segment.

Thank you so much for listening and for thinking about the show.

Speaker 2 I want to thank Lale Arakoglu and I also want to mention two books that were helpful with our segment about luggage. Robert J.

Speaker 2

Schiller's The New Financial Order and Catherine Marsal's Mother of Invention. Decodering is is produced by Willipaskin and Katie Shepard.

This episode was also produced by Rosemary Belson.

Speaker 2

We had editing help from Joel Meyer. Derek John is Slate's executive producer of narrative podcasts.

Merrick Jacob is senior technical director.

Speaker 2 If you haven't yet, please subscribe and rate our feed in Apple Podcasts or wherever you get your podcasts. And even better, tell your friends.

Speaker 2 And if you're a fan of the show, I'd also love for you to sign up for Slate Plus. Slate Plus members get to listen to Decodering without any ads and their support is crucial to our work.

Speaker 2 So please go to slate.com slash decoder plus to join Slate Plus today. See you next week.

Speaker 28

You're juggling a lot. Full-time job, side hustle, maybe a family.

And now you're thinking about grad school? That's not crazy. That's ambitious.

Speaker 28 At American Public University, we respect the hustle and we're built for it. Our flexible online master's programs are made for real life because big dreams deserve a real path.

Speaker 28 Learn more about APU's 40-plus career-relevant master's degrees and certificates at apu.apus.edu. APU built for the hustle.