Xi Jinping’s paranoid approach to AGI, debt crisis, & Politburo politics — Victor Shih

On this episode, I chat with Victor Shih about all things China. We discuss China’s massive local debt crisis, the CCP’s views on AI, what happens after Xi, and more.

Victor Shih is an expert on the Chinese political system, as well as their banking and fiscal policies, and he has amassed more biographical data on the Chinese elite than anyone else in the world. He teaches at UC San Diego, where he also directs the 21st Century China Center.

Watch on YouTube; listen on Apple Podcasts or Spotify.

Sponsors

* Scale is building the infrastructure for smarter, safer AI. In addition to their Data Foundry, they just released Scale Evaluation, a tool that diagnoses model limitations. Learn how Scale can help you push the frontier at scale.com/dwarkesh.

* WorkOS is how top AI companies ship critical enterprise features without burning months of engineering time. If you need features like SSO, audit logs, or user provisioning, head to workos.com.

To sponsor a future episode, visit dwarkesh.com/advertise.

Timestamps

(00:00:00) – Is China more decentralized than the US?

(00:03:16) – How the Politburo Standing Committee makes decisions

(00:21:07) – Xi’s right hand man in charge of AGI

(00:35:37) – DeepSeek was trained to track CCP policy

(00:45:35) – Local government debt crisis

(00:50:00) – BYD, CATL, & financial repression

(00:58:12) – How corruption leads to overbuilding

(01:10:46) – Probability of Taiwan invasion

(01:18:56) – Succession after Xi

(01:25:10) – Future growth forecasts

Get full access to Dwarkesh Podcast at www.dwarkesh.com/subscribe

Press play and read along

Transcript

Speaker 1 Today I'm talking with Riktor Xi, who is a director of the 21st Century China Center at UC San Diego.

Speaker 1 China is obviously the most important economic and geopolitical issue of our time, and doubly so if you believe what I believe about AI.

Speaker 1 I was especially keen to talk to you because you have deep expertise not only in Chinese elite politics, but also its economic system, its fiscal banking policies.

Speaker 1 We'll get into all of that before we get into the AI topics. Is China actually a more decentralized system than America?

Speaker 1 If you look at government spending by provincial governments versus the national government in China, it's like 85% local versus provincial, 15% national.

Speaker 1 In the U.S., it's actually, if you look at state and local, it's 50%.

Speaker 1 National, federal government is 50%.

Speaker 1

When you think of an authoritarian system, you often think of it as like very top-down. The center controls everything.

But if you look at these numbers, it just seems like it's quite decentralized.

Speaker 1 Or is that the wrong way to look at the numbers?

Speaker 2 I think for a while, China was quite decentralized.

Speaker 2 So this is kind of in from the mid-1970s all the way until the mid-1990s, China was very decentralized, where local governments generated a lot of revenue, but they also spent a lot of money.

Speaker 2 And it incentivized them to do, you know, kind of basically good things, such as trying to attract as much FDI as possible, trying to attract as much local investment as possible, give tax breaks, and so on and so forth.

Speaker 2 So I think

Speaker 2 China had a very good period of mainly sort of private sector-driven growth because of this fiscal decentralization. And that's the understanding of, I think, most economists.

Speaker 2 But then there was a tax centralization in 1994, basically, where the central government basically said, okay, this is ridiculous.

Speaker 2

We don't want to end up like the Soviet Union, you know, and fall into different pieces. We need to control fiscal income.

So then they grabbed the most lucrative source of taxation at that time.

Speaker 2 And it continues to be the case, which is the value-added tax.

Speaker 2 And so the collection of value-added taxes, and then also

Speaker 2 in subsequent decades, pretty much all other tax categories are now collected by the central government.

Speaker 2

Then they reimburse part of the money to the provinces. And then supposedly they say, okay, now you can spend the money as you wish.

But in reality, that's not the case.

Speaker 2 So in reality, it's kind of like, well, if you do this thing, then I'll give you a little bit of money.

Speaker 2 But you have to do the thing that I want you to do to get this money, to get this grant, basically. So then the fiscal autonomy, I would say, has been falling since 1994.

Speaker 2 I mean, there are different periods. Sometimes, you know, there's a little bit more autonomy.

Speaker 2 So, you know, sort of from 2000 to

Speaker 2 until recently, until 2020, the localities gained more autonomy vis-a-vis land sales. So that's when the real estate market was going very well.

Speaker 2 Even though they couldn't control the tax revenue, they could control the land revenue.

Speaker 2 But then the central government basically killed the land market in 2022.

Speaker 2 And now I think localities in China are highly dependent on the central government.

Speaker 1

Let's start at the very top. If you look at the members, first I want to understand the personnel.

If you look at the members of the Politburo

Speaker 1 And you look at their past, a lot of them will be provincial leaders and then some local thing before that. But in many cases, they'll have stints, as you said, as they were the head of this

Speaker 1 chemical engineering SOE, or they studied. Xi Jinping himself

Speaker 1 has a PhD in chemical engineering, right?

Speaker 2 Something, some kind of, well, but I, yeah, I don't know.

Speaker 1 Yeah, that's actually what I asked about. If you just look through the list, a lot of them are like PhD economists, PhD industrial engineer, et cetera, et cetera.

Speaker 1 I mean, some of them, if you look, it's like, oh, they're a PhD in Marxist theory.

Speaker 2 Yeah, Marxist thoughts.

Speaker 1 Which that seems fake. But

Speaker 1 are they actual technocrats? If you look at their degrees, they seem quite impressive.

Speaker 1 Or is this just like fake made-up credentialism?

Speaker 1 If there's like a PhD economist in the Politic Bureau, should I be like impressed and be like, oh, they probably really understand economics? Or should I just think some of them are not?

Speaker 2 So the former

Speaker 2 premier of China, Li Ke Chang,

Speaker 2 his undergraduate degree, I think, was economics, and he studied under one of the best economists in China.

Speaker 2 So I think he understood economics.

Speaker 2 So I would say in the Politburo today, there is this wing of the Politburo who are military industrialists, who were trained as engineers, and they indeed

Speaker 2 were trained in the best programs in China. So Ma Xing Rui, the party secretary of Xinjiang, for example, in the Politburo,

Speaker 2 you know, graduated from Tsinghua University.

Speaker 2 Zhang Guo Qing, also who worked in a military industry for years,

Speaker 2 I don't know if it's Tsinghua, one of the other top science programs in China. So they know a lot about science, but does that mean that they know a lot about governing?

Speaker 2 I mean, that's, I think, a somewhat different question.

Speaker 2 But then you also have other cases like Ding Shuxiang, right? So we can talk about him because he's in charge of cybersecurity in China. He has a technical background, but in metallurgical forging,

Speaker 2 graduating at, I wouldn't say it's not the MIT of China, maybe closer to the IIT of China, you know, just kind of like the second-tier science institute founded by one of the Soviet experts who wanted to teach China how to do metallurgy.

Speaker 2 But does that kind of very specialized technical knowledge make you a better leader? I think it depends on the person.

Speaker 2 And I think what happens in the the Chinese Communist Party is that as people rise up, there's certainly, you have to have political acumen.

Speaker 2 If you don't have political acumen, you're not going to make it.

Speaker 2 And some people, on top of their technical expertise, it turns out that they have some political acumen, but it's not something that you sort of know ex-ante.

Speaker 2 except for the princelings, right? So the princelings, the reason why they're special is not just because of their

Speaker 2 genes, you know, they're children of high-level officials, is that they grew up honing this political acumen because their parents could teach them about it.

Speaker 2 So then some people turn out to have political acumen, they're pretty smart, they don't necessarily have the best degree, you know, degrees from the best universities in China, and they end up being very successful.

Speaker 2 So it's not necessarily, oh, you know, all the Peking and Tsinghua University graduates, you know, they all get to the very top.

Speaker 2 There are certainly disproportionate amount of people like that in the Pulitz Bureau, but they don't dominate because at the end of the day, it is somewhat random.

Speaker 1 Yeah. I still

Speaker 1 feel confused about how to model the competence of the party

Speaker 1 because, on the one hand, they are

Speaker 1 super educated in STEM and are selected at least partly on merit, et cetera. On the other hand, we just see them

Speaker 1

a lot of zero COVID was just genuinely stupid, scrubbing down airport runways and so forth. And it just lasted for too long.

And why was nobody steering the ship then? So

Speaker 1 what's the way to put together this picture?

Speaker 2

So there's a lot of expertise at sort of the lower level that can feed to the higher level. And there's some channels for doing that.

I would say a lot of channels for doing that.

Speaker 2 So they're not so dysfunctional on that score. But what time and again leads to suboptimal policy is the party's

Speaker 2 sort of instinct to preserve itself,

Speaker 2 but then in a way worse than that, to preserve its power.

Speaker 2 So it's not like, oh, well, we do this kind of thing,

Speaker 2 you lead to a better sort of outcome, public health outcome, and we get to survive. you know, politically.

Speaker 2 But if they see, it's like, okay, even if we do survive politically, but it leads to a diminution of our power in one respect, you know, we have less control of the banks or like the scientists become more independent or something like that, then they would say, let's not do that.

Speaker 2 You know, because it's like, what's the cost? You know, some people die, you know, whatever. We have slower growth for a couple of years, but we get to preserve this power.

Speaker 2 We will go ahead and preserve power.

Speaker 1 But if you're an economist, okay, so here's a question.

Speaker 1 The traditionally, the way I understand it, if you study economics in at least an American university, you'll learn about like

Speaker 1 demand, here's why certain regulations can be bad, here's why tariffs are bad, just the basic 101 teaches you that.

Speaker 1 So if a lot of the members at the highest levels of the Communist Party have this basic understanding, then what's the reason that they make mistakes that many economists say they shouldn't do?

Speaker 1 Like why

Speaker 1 obviously people talk about rebalancing a lot.

Speaker 1 Why don't they think that increasing consumption is a good idea?

Speaker 2 Well, so there's a traditional reason, and then there's today's reason, which is on top of the traditional reason. The traditional reason is that,

Speaker 2 you know, so education in China, you get tracked into sciences, STEM, or you get into social science or humanities. If you get tracked into STEM, you may never learn anything about supply and demand.

Speaker 2

It's just not required. You just learn a bunch of math.

You learn a lot of engineering if you want to be an engineer.

Speaker 2

And then there's some art classes for you to select. You can select the art classes or, you know, maybe one econ class.

For a while, learning economics was popular.

Speaker 2 So in the 1990s, all the engineering students would have taken an econ class. But people who were trained before that, they were not.

Speaker 2 The one class that is still required for everybody is government ideology. Right, so

Speaker 2 in fact, the requirement for government ideology has been ratcheted up in recent years.

Speaker 2 So that now, because I look at all the applications of students from China and I look at what classes they've taken, now once a year they have to take a class called Situation and Policy, which is basically just the Chinese government's perspective on all kinds of different issues.

Speaker 2

But that's not economics. It's not accounting.

It's not some basic skill. It's just telling people what the government prefers in a given topic.

So that's a traditional reason.

Speaker 2 So you can have some very high-level officials, even if they have PhD in nuclear engineering, they may not know very much about how the market works, how society works, so on and so forth.

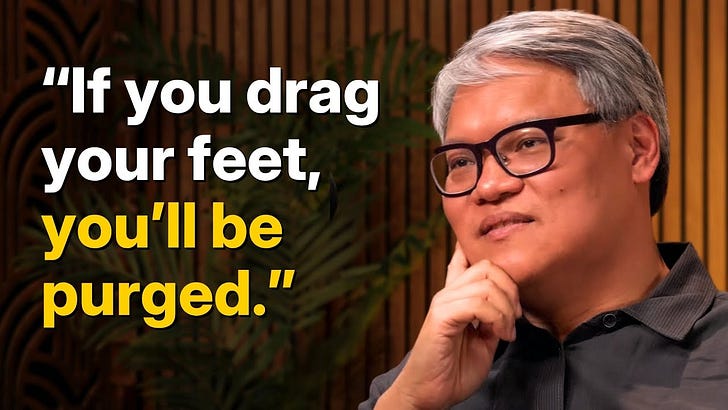

Speaker 2 The new reason is that we have one very, very powerful figure in the Chinese Communist Party, such that even if you're a Politburo member, which used to give you some autonomy in the domain that you govern over, that is no longer the case.

Speaker 2 You know, if

Speaker 2 Xi Jinping expresses a preference over a policy direction, that is a direction you have to go toward no matter what.

Speaker 2 Because if he observes that you're dragging your feet or that you're pursuing a slightly different agenda, you will be perched. And we've seen cases of that.

Speaker 1 At some point, we'll talk about leading small groups

Speaker 1 and

Speaker 1 the way they work. But the picture you get from the fact that

Speaker 1

Xi is monitoring what all these different Polybium members are doing. He's noticing whether they're dragging their feet.

He's leading all these small teams.

Speaker 1 You'll explain this in a second, how these work, but they organize different

Speaker 1 leaders who are the heads of the ministries or commissions that are relevant to a specific project working. And I guess every week they meet and they hammer out who's a bottleneck, what do we need to

Speaker 1 do to get a project moving. So Zia has ratcheted up on the amount of such meetings that, and he's, the picture you get is somebody who is micromanaging

Speaker 1 details across all these policy areas.

Speaker 1 If you read Stalin biographies, there's a big thing like Stalin actually was a person like this, obviously not to great effect, but he was interested in micromanaging every single detail across even the theater productions in the country to like steel production, everything.

Speaker 1 Is that who Xi is?

Speaker 2 Yeah, so if you look at what he does day to day, he spends a lot of time in meetings. Yeah.

Speaker 2

And it's astonishing. I mean, there's no, this is one thing.

It's like there's the Chinese leadership, they're not going to play golf, you know, three days out of a week.

Speaker 2 I mean, Xi Jinping and his colleagues are having meetings about policies almost every, you know, like 270 days out of the year.

Speaker 1 So the study sessions with the Political Bureau,

Speaker 1 these meetings, et cetera,

Speaker 1 are they like, are they substantive? Are they real?

Speaker 1 Is he like actually learning the intricacies of like, here's the, you know, here's how zero code has impacted this province and here's why we should whatever, whatever. Or are they just faux?

Speaker 1 Because if you read the announcements from the party or departments, it was just like so vapid, like typical communist speak.

Speaker 1 How real are these meetings?

Speaker 2 So I've talked to some people who've lectured to the Politburo. I think they're somewhat real because they don't know ex-ante what questions they'll be asked.

Speaker 2 Like, I'm talking about the speakers, right?

Speaker 2 So I think the, you know, Xi Jinping and other leaders, they know what the speaker would say in the main remarks, but then there's a Q ⁇ A portion of it, which actually is real, like it's not staged.

Speaker 2 So that's pretty scary, you know, if you're some professor, you know, Xi Jinping has you to come in and ask you a bunch of random questions. It's very scary.

Speaker 2

So I think they're substantive. And then, well, but the thing is also, Xi Jinping will make remarks after such a lecture, and those remarks become policy.

Yeah.

Speaker 2 So you asked about the leading small group. So this is where this ranking is very important, right? So the head of the leading small group always has to be the senior most ranked person.

Speaker 2 And of course,

Speaker 2 the good thing about having Xi Jinping as the head of a leading small group is that his authority is not going to be challenged by anyone else because everyone agrees he's the most powerful and most senior ranked person in all of China.

Speaker 2 But the problem is all the other members of the leading small group are lower ranked than him.

Speaker 2 So then,

Speaker 2 so whereas before, well, not all, but like whereas before when decisions were made in the Politburo Standing Committee, notionally the party and also even the bureaucratic ranks of all the Politburo Standing Committee members are equivalent to each other.

Speaker 2 So there was debates,

Speaker 2 there were debates, and then

Speaker 2 even sometimes overturning of the position of the party secretary general.

Speaker 2 Sort of historically, you have seen cases like that.

Speaker 2 But when most of the decision was pushed into all these different leading small groups, usually there's one other person who's similarly ranked as Xi Jinping, you know, the Premier of China or one of the other people.

Speaker 2 But everyone else would be these vice premier ministers or provincial governors who are definitely ranked lower than Xi Jinping.

Speaker 2 And, you know, in no scenario will they debate a particular policy with Xi Jinping.

Speaker 2 So at most, maybe there's one person with sort of equal standing officially with Xi Jinping who could voice some kind of disagreement.

Speaker 2 But of course, because she is so powerful informally, no one would actually dare to do that.

Speaker 2 And so basically, the whole thing, once all the decisions got pushed into leading small groups, basically became Xi Jinping.

Speaker 2 And it's very hard on him because basically

Speaker 2

Before all these meetings, there's a briefing. You know, someone gets out a briefing book and says, okay, this is what we're going to talk about.

Here are the policy options. Which one do you want?

Speaker 2 He has to make up his mind. I mean, sometimes I'm sure he consults with other people and so on and so forth.

Speaker 2 So then he has to be really engaged with a large number of policy areas on a day-to-day basis because the decisions that he make

Speaker 2 becomes the law, basically. Yeah.

Speaker 1 And it's stupendous to think about we understand you can like tell somebody how big is China, the population, et cetera, the size of the economy.

Speaker 1 I think visiting China gives you a tangible sense of just how big.

Speaker 1 You have provinces, each of which have as many people as a normal nation state, provinces which have hundreds of millions of people, 40,000 people, 40 million people, 50, you know, so forth.

Speaker 1 And then one person will say something at the end of a meeting that determines a policy for basically like everyone. Yeah, for like the population of like North and South America or something.

Speaker 1 Does he say things at the end of meetings, during his speeches, et cetera, which indicate that he actually has

Speaker 1 a good understanding of these different policy areas?

Speaker 1 Because obviously the official speeches are very vague and it's always something like, we will make sure that we are robustly pursuing Chinese growth while

Speaker 1 hewing to the tenets of Mao's thought and while not, so

Speaker 1 never anything specific or interesting or

Speaker 2 but do we have an indication that behind closed doors he's well you don't think is anything specific or interesting, but if you have read thousands of these things, sometimes it's quite revealing, actually.

Speaker 2 Sorry, So I am

Speaker 2 general.

Speaker 1 I'm interested in what it reveals about him personally.

Speaker 1 Did he display any analytical ability,

Speaker 1 any sort of like empirical understanding of different policies, et cetera?

Speaker 2 Aaron Powell, yeah, that is difficult.

Speaker 2 So I would say, because of his upbringing as a princeling, for internal party matters, how to control the party, how to control the military, from the speeches, you know, some of these, they're not secret speeches, but they're like sort of more geared toward other members of the Chinese Communist Party.

Speaker 2 So some of these speeches, like if you go to China, you can read some of these speeches,

Speaker 2 which I have.

Speaker 2 He has a really good political nose. Like he knows what it takes to control the party apparatus, control the military.

Speaker 2 On

Speaker 2 especially economic issues, yeah, it seems like, you know, some advisor gives him some talking points, he talks through it. There's some sense of that.

Speaker 2 On technology issues, I think he cares a lot about it, but only from the perspective that competition with the United States is a very important objective.

Speaker 2 The Chinese Communist Party is for him personally a very important objective. So he wants to win.

Speaker 2 But precisely the extent to which he understands all the intricacies, it's unclear to me.

Speaker 2 I don't think he necessarily,

Speaker 2 he, you know, I don't think he does.

Speaker 2 But then, you know,

Speaker 2 comparing him to American leaders, especially today, I think he's probably better prepared. Just because

Speaker 2 in China, the experts, they talk to the top leadership all the time. Yeah.

Speaker 1 The advantage of the American system, of course, is that,

Speaker 1 at least in theory, it can survive a leader who is not up to the snuff. Publicly available data is running out.

Speaker 1 So major AI labs like Meta, Google DeepMind, and OpenAI all partner with Scales to push the boundaries of what's possible.

Speaker 1 Through Scale's data foundry, major labs get access to high-quality data to fuel post-training, including advanced reasoning capabilities.

Speaker 1 Scales research team SEAL is creating the foundations for integrating advanced AI into society through practical AI safety frameworks and public leaderboards around safety and alignment.

Speaker 1 Their latest leaderboards include Humanities Last Exam, Enigma Eval, Multi-Challenge, and Vista, which test a range of capabilities from expert-level reasoning to multimodal puzzle solving to performance on multi-turn conversations.

Speaker 1 Scale also just released Scale Evaluation, which helps diagnose model limitations.

Speaker 1 Leading frontier model developers rely on scale evaluation to improve the reasoning capabilities of their best models.

Speaker 1 If you're an AI researcher or engineer and you want to learn more about how Scale's Data Foundry and Research Lab can help you go beyond beyond the current frontier of capabilities, go to scale.com/slash Thwarkash.

Speaker 1

Okay, let's go back to Ding Zhaozhang. How do you pronounce his name? Ding Zhu Shang.

Okay, sorry about it. So, Politburo has what, 25 members? 20, 25?

Speaker 2 Yes, 25 members.

Speaker 1 Okay, so the standing committee has seven members. This is the key group inside the Politburo.

Speaker 1 And

Speaker 1

this person is one of those seven. He runs the Center for Science.

Sorry, the Central Science and Technology Commission.

Speaker 1 The reason I'm especially interested in him is because any large-scale AI effort that China would launch would be under his purview. Do we understand

Speaker 1 what he wants, who he is, what his relationship with Xi is, what he would do if AGI is around the corner, et cetera? Yeah, these are all very good questions.

Speaker 2 So I think in addition to the Science and Technology Commission that you mentioned, another very important position that he holds is that he's the head of the office of the Central Commission on Cybersecurity.

Speaker 2 The head of the Central Commission on Cybersecurity is Xi Jinping himself, but the head of the administrative office, which runs the day-to-day operation of that commission, which is basically a leading group, is Ding Shu Xiao.

Speaker 2 So, and he took that position back in 2022. So, he's been steeped in cybersecurity for a couple of years.

Speaker 2 I think by now he knows all the major players

Speaker 2 and some of the key policy issues.

Speaker 2

His relationship with Xi Jinping is a very interesting one. So he only directly worked under Xi Jinping for one year.

When Xi was in Shanghai, he was basically the

Speaker 2 very senior level secretary who would support whoever the party secretary of Shanghai was. And he worked under three different party secretaries of Shanghai, supported Xi Jinping

Speaker 2 for one year. For some reason, Xi Jinping just trusted him absolutely after that.

Speaker 2 And it's a mystery. And I've looked at all the open literature, I've asked people in Shanghai, nobody knows why that's the case.

Speaker 2 I mean, almost certainly, I think one reason is that he was gathering a lot of information about the other leaders of Shanghai and sending all of that information to Xi Jinping

Speaker 2 to

Speaker 2 basically let him know because at that time, as you know, the previous leader of China, Jianzhemin, had a very big stronghold in Shanghai.

Speaker 2 So basically, Xi Jinping had to sort of break that apart before he could assert control over Shanghai.

Speaker 2 Ding Xiu Xiang likely was one of the people who sent all this necessary information to Xi Jinping in order for him to do that.

Speaker 2 But beyond that, I mean, lots of people do that for Xi Jinping, truth be told. So beyond that, what else has he done for the big boss to earn his trust, I think, is a big mystery.

Speaker 2 But the manifested outcome is that she trusts him a great deal because in 2013, he was promoted to Beijing to be the second in command in his personal office, handling all the flows of data in and out of the desk of Xi Jinping.

Speaker 2

So that's a very important position. He became the first in command a couple years later.

He took control over the entire apparatus that governed Xi Jinping's day-to-day life back in 2017.

Speaker 2 Now he's the vice premier in charge of cybersecurity. So clearly, this guy is trusted.

Speaker 2 You know, his preference for AI, AGI, so I tweeted this Dabo speech, which you also looked at.

Speaker 2 I think it's very revealing, right? So you look at it, you're like, wow, what's so what he said was,

Speaker 2 we need to invest in AI,

Speaker 2

but we need to do it. We can't go all out and investing in it without knowing what the breaks are.

We have to develop the breaks also at the same time.

Speaker 2 I think that's extremely revealing. So basically, it's very different from the American approach because in America, it's all driven by the private sector.

Speaker 2 And of course, all these, you know, except for one or two companies, everyone just invests, invest, invest, and try to reach AGI as soon as possible.

Speaker 2 For the Chinese government, they're very afraid that some actor outside, but even inside the party, is going to use it as a tool to usurp the power of the party.

Speaker 2 So they want to know that they have a way of stopping everything if it comes to it. So for them, developing the brakes is just as important as developing AI itself.

Speaker 1 What are the different organizational milestones we should be watching for to understand

Speaker 1 how they're thinking about AI, when things have escalated?

Speaker 1 So to add Mark Ale to this question, what what I expect to happen, let's say next year, in terms of raw AI capabilities, we might have computer use agents. So,

Speaker 1 a thing which is not just a chatbot, but can actually do real work for you. You put it loose on your computer, it'll go through email and compile your taxes, et cetera.

Speaker 1 And then, you know, dot, dot, dot, in five years, I expect it to be able to do all white collar work or most white collar work, which is like, you know, 40% of the economy potentially.

Speaker 1 Eventually, we'll have full AGI, even robotics and so forth. As this is happening, how should we be tracking how the

Speaker 1 party is thinking about what is happening, how seriously they take it, what they should do about it?

Speaker 1 Should we, I think last week or a couple weeks ago, there was a Politburo study session on AI, but I don't know if there was like AGI AI or what kind of AI they were discussing.

Speaker 1 Should we be looking for a leading group on AGI in particular? Should we be trying to just read more speeches? What should we be paying attention to?

Speaker 2 Thus far, it seems like it's under cybersecurity leading group. So Ding Shu Chang would be in charge of it.

Speaker 2

I don't think so. Because for the party, it's a security aspect of it that's the most important.

I mean, there's one aspect where it's like, yeah, it'd be great to automate all industrial production.

Speaker 2 China is doing a good job doing that already. I don't think they need additional infrastructure, you know, sort of governing infrastructure to allow them to do that.

Speaker 2 But on sort of applying

Speaker 2 AGI or AI to governance, to even service sector, you know, generating video content for people, doing, you know, even like travel agency stuff.

Speaker 2 The party is very, very paranoid that some hostile actor outside of China, certainly they believe that very strongly, or inside of China, is going to do something and the AGI is going to take off and it's going to undermine the party's authority.

Speaker 2 So the what they, I think basically what we're going to see in terms of institutional development is not at the top end, but on the lower end.

Speaker 2 So So they will want to designate human beings in all the government agencies, in all the commercial entities that are using AI or AGI

Speaker 2 to

Speaker 2 put their foot on the brake if it comes to it.

Speaker 1 Aaron Ross Powell, Jr.: But so far, after the deep seek became a big deal,

Speaker 1 the immediate reaction, it seems, in China,

Speaker 1 all the different big tech companies, WeChat, Tencent, everybody was encouraged to adopt it, and they did

Speaker 1 adopt it as fast as possible. Xi himself met with Lien Wenfang and

Speaker 1 did a whole meeting where all the industrial heads were there, and Xi said we have to accelerate, I don't know, whatever, technology in China, et cetera.

Speaker 1 So it seems like so far the response has been the greater the capabilities of AI, the more they're excited about it, the more they think this is the beginning of Chinese greatness.

Speaker 1 But you think that changes at some point?

Speaker 2

No, no, no. I mean, they want to develop it, of course.

They'll pour a lot of money. They'll try to give DeepSeek DeepSeek as much help as possible, sourcing GPUs,

Speaker 2 whatever, all this kind of stuff. But I am all but certain that there is one, maybe a team of people in the headquarters of DeepSeek who can pull the plug

Speaker 2 if necessary. Because there is such a team of people in every major Internet company in China.

Speaker 1 What would cause them to pull the plug?

Speaker 2 Yeah, so if AGI started generating Fal and Gong-related content and it proliferates very quickly beyond the capacity of the sensor to control it, then they'll have to stop

Speaker 2 the algorithm from generating new images and new videos and so on and so forth.

Speaker 1 Suppose it turns out you were saying, look, they can help HighFlyer source GPUs and et cetera.

Speaker 1 What is the mechanism by which

Speaker 1 suppose it turns out that

Speaker 1 for HighFlyer to continue D-Seek to continue making progress, they need all the GPUs that Huawei can produce, and they need a whole bunch of other things. They need energy, they need data centers.

Speaker 1 What would it actually look like for the government to say every single Huawei GPU has to go to DeepSeek? They're going to get access to all this spare land to build data centers.

Speaker 1 Who would coordinate that? Would that be the leading cybersecurity group? Would that be somebody else?

Speaker 2

Yeah, it could be. Yeah, so that's interesting.

So

Speaker 2 the physical investment will have to share power with some other leading group.

Speaker 2 Yeah, so I guess that would be a justification for an AGI leading group of some sort because, you know, building power center that falls under NDRC,

Speaker 2 it could be under Li Chang or He Lifeng,

Speaker 2 you know, which is especially He Lifeng, which is in charge of like investment and financing.

Speaker 2 So, but if Xi Jinping doesn't want He Lifeng to share that power, then we'll have to give it all to Ding Shi Xiang.

Speaker 2 and then give him a lot of power. I mean, he can just do it by fiat or create a a separate organization to make it happen.

Speaker 2 At this point, as you know, you know, data centers are being built in China at a very fast clip, and I think they're just using existing command structure.

Speaker 2 There is potentially a foreign aspect of this, right? So it's like you build up all this cloud computing capacity in the Gulf states. Who's going to be the customer?

Speaker 2 You know, who's willing to pay billions of dollars to

Speaker 2 use it? China, right? So

Speaker 2 So then the foreign policy apparatus will have to coordinate that and so on and so forth.

Speaker 1 Development road view, too.

Speaker 2 Yes, exactly.

Speaker 1 Does it have any end implication to the progression of AI, who actually ends up controlling

Speaker 1 these leading groups, whose purview it ends up under? Or is it just basically a detail? But in terms of

Speaker 1 what happens with AI in China, it doesn't have that big an implication.

Speaker 2

I think it does matter. Yeah.

So you have some decision makers who have shown to be not very good

Speaker 2 and even politically not very good, but nonetheless, for some reason, they're trusted. I mean, maybe precisely because they're not very good.

Speaker 2 They're very dependent on Xi Jinping that they get promoted.

Speaker 2 The chief negotiator with the United States, Huelifeng, Vice Premier in Charge of Finance, he is well known for

Speaker 2 starting and perpetuating the largest real estate bubble the world has ever seen in Tianjin. I don't know if you went to Tianjin, they're like just empty buildings everywhere.

Speaker 2 So there's the new Manhattan, you know, literally the size of Manhattan, filled with empty office buildings.

Speaker 1 He made that ironically sounds like a great tourist site. Not for

Speaker 2 Manhattan, but because it's actually cool to visit.

Speaker 2 But, you know, it's like, wow, this is great. Like, what are you going to do with the buildings?

Speaker 1 We went to

Speaker 1 this in Amisham. We went to this

Speaker 2 huge, huge Buddhist temple.

Speaker 1 By huge, I just mean like

Speaker 1 there would be this structure, the shrine, and you'd go through it and you'd realize behind it was an even bigger shrine that was hiding from view.

Speaker 1

And then you'd go through that one, there'd be an even bigger one. This happened like five times.

If you were to drive through this, it would take you like

Speaker 2 not historical, right?

Speaker 1

Oh, no, yeah, yeah, it's new. And then I asked like the head, by the way, there was nobody else there.

Yeah, yeah, it was me, three white guys, and nobody else. And I asked the head monk,

Speaker 1 how did you guys finance this? And he says, we've got a lot of supporters, a lot of donations.

Speaker 2

I don't think so. Yeah.

Yeah, so then it really depends. Like, who's in charge of AGI? Yeah, so Ding Zhuxiang really is a mystery.

I think he has great political acumen.

Speaker 2 He must, you know, in order to gain Xi Jinping's trust. He has some technical background, but it's metallurgical forging.

Speaker 2

But he's worked in Shanghai for decades. So he knows how private corporations run.

He knows a lot about international trade, FDI.

Speaker 2 So I think, you know, if you look at the sort of people in the Politburo, Politburo Standing Committee, I would say he's definitely in the top quartile of people that you would want to be in charge of AI, if not the top, you know, two or three people.

Speaker 1 Right. Interesting.

Speaker 2 I mean, one thing that I would say about

Speaker 2 AI

Speaker 2 is that

Speaker 2 content creation is a big, it's going to be a big roadblock for China because China is so paranoid about the content that flows on the internet that they put human beings all over the place to slow things down, slow the transmission down.

Speaker 2 And then now if you have AI creating tons of content, there will still be human beings, algorithms, and human beings double, triple checking the content

Speaker 2 because they're just so afraid of some subversive content getting out.

Speaker 1 But it's still been compatible with them innovating and having leading companies in even content, right? Like

Speaker 1 RedNote and TikTok and so forth,

Speaker 1 not to mention WeChat. So

Speaker 1 if AI ends up, and AI might be even more robust. to some of these

Speaker 1 sensitive content because you can just teach the AI to not say certain kinds of things but even if that were the case even if you train something that you think is pretty good they will still want a human being checking everything as somebody who is

Speaker 1 trying to observe what the party is doing have you found that using lms has been helpful and if so which model g gives you the best insight into what the ccp is thinking

Speaker 2 uh yeah no i i've been using uh ai quite a bit i mean both to sort of code data you know it used to be like text hand code stuff and now a lot of it can be automated.

Speaker 2 But in terms of finding out what the Chinese government is doing,

Speaker 2 I think some of the American models are okay, like Rock is okay, but the most helpful has been DeepSeek.

Speaker 2 So to me, it's quite clear that DeepSeek, which of course was

Speaker 2 first developed by a hedge fund to trade in the Chinese market, part of what they really trained the model for was to detect important policy documents and meetings within the Chinese government.

Speaker 2 Because when you enter, you know, the right, or even not even like especially sophisticated prompts, you know, just like, you know, what is the Chinese government doing when it comes to AI?

Speaker 2 It comes up with a bunch of very high-quality links, which is very useful for my research.

Speaker 2 So then, you know, immediately you get a sense of like, what are the latest policies, what are the latest statements by high-level officials.

Speaker 2 It seems that DeepSeek puts some higher weighting, let's say, on this kind of content.

Speaker 2 So I have, have, you know, I don't dare to install it on my phone, but I certainly have collaborators who have downloaded the open source model and install into a hard drive.

Speaker 2 And I use the web interface for some of my research.

Speaker 1 Do you think it's just because they have more Chinese language data, and so it's just better at understanding the party communications?

Speaker 2 So, I've used

Speaker 2 sort of Baidu's thing.

Speaker 2 And so, I think the typical Chinese language models are more trained on social media content, which will come back with hits that are more social media.

Speaker 2 It's like, oh, if you ask about AI, we'll talk about how AI gets used in different things instead of this kind of policy documents and meetings and so on and so forth.

Speaker 2 So it seems just from an inductive observation that DeepSeek

Speaker 2 is trained on this kind of content.

Speaker 1 So that HighFlyer can make trades.

Speaker 2 Trevor Burrus, Jr.: Yes, so the HighFlyer can. I mean, obviously, China being China, government policies have a huge impact on how different stocks do.

Speaker 2 And that's often where you would find the alpha. In the old days, people used to call up their friends who work for this and that ministry to get insider information.

Speaker 2 But I think what HighFlyer has discovered would also generate alpha is to really use algorithm to look closely at these policy documents.

Speaker 1 Look, coffee isn't the reason that you're going to stay at the Ritz, but it could be the reason that you leave.

Speaker 1 Because when you offer a truly free main product, your customers require excellence in all the parts, not just the core.

Speaker 1 So the RITS works with a specialty roaster to ensure that they can deliver great coffee.

Speaker 1 That's what WorkOS does for your product, but for enterprise features, like single sign-on, access controls, and audit logs. These features are not the reason that people will love your product.

Speaker 1 But if you don't have them at all, you simply won't get a seat at the table with your biggest, most important customers.

Speaker 1 Companies like OpenAI, Anthropic, Vercel, and Perplexity all rely on WorkOS to serve their enterprise customers. In fact, Nvidia might be the only other vendor that all of these AI companies share.

Speaker 1 And that's because not only are these features critical, they require excellence.

Speaker 1 WorkOS makes it super easy to plug in these features into your product and get back to delivering the premium experience that your customers expect.

Speaker 1 If you want to learn more, go to workOS.com and tell them that I sent you. All right, back to Victor.

Speaker 1 Okay, and then this is going to sound like a naive question, but we're talking about how the party in the abstract wants to maintain control over every aspect of Chinese life and Chinese economy.

Speaker 1 But of course, the party is made up of individuals.

Speaker 1 And many of these individuals, Xi himself, went through periods where the party had extraordinary control over people's life during the Cultural Revolution and so forth.

Speaker 1 And they personally and their families suffered as a result of this.

Speaker 2 And

Speaker 1

they're educated people. Many of them had been in industry, right? These are not naive people.

So maybe I'm just projecting too much of my Western bias here.

Speaker 1 But what is the reason that they think it's so crucial that

Speaker 1 the banks are run by the party and the AI is run by the party and nothing escapes the party state?

Speaker 2 Yeah, so the Cultural Revolution generation, I think a lot of people suffered horrendously, including Xi Jinping himself.

Speaker 2 But then basically, you have two types of lessons that people drew from it. So the first lesson is like, oh, you know, the party is too dictatorial.

Speaker 2

You know, China needs to liberalize and so on and so forth. So you have a lot of people from that generation who feel that way.

Many of them now live in the United States. You know, basically,

Speaker 2 they tried to leave China as soon as possible in the 1980s and succeeded.

Speaker 2 But for someone, apparently, for Xi Jinping himself and others like him, the lesson was just don't be on the losing side.

Speaker 2 You know, in any political struggle, make sure you're on the winning side, because if you are on the winning side, then you can do terrible things to your enemies.

Speaker 2 So that apparently is the lesson that he learned.

Speaker 2 And he basically honed his skills and built his coalitions for the time that he would take over high-level positions in the party for decades, as it turns out. So if you look at the data, you know,

Speaker 2 when he was in Fujian province, He spent an enormous amount of time hanging out with military officers in Fujian back in the 1980s, you know, late 1980s, early 1990s.

Speaker 2

And then you're like, well, why did he bother to do that? You know, most local officials, they don't do that. I mean, you know, the military is there.

You need to be nice to them and all this stuff.

Speaker 2 But like, he built a dormitory for them. He even joined a unit of anti-aircraft regiment.

Speaker 2 He tried as much as possible to do as much as possible with the military because he knew he needed the support of somebody in the military when the time comes. And guess what?

Speaker 2 Sort of 30 years later, when he was about to be elevated to be Secretary General of the Chinese Communist Party, many of the people that he knew back in Fujian are now generals.

Speaker 2 They're in charge of important military units. And once he came to power, then he really promoted some of these people.

Speaker 2 But then lately, of course, he's purging some of these people, which is really interesting.

Speaker 2 Yeah, he had a strategic vision about his own career trajectory, and he pursued that

Speaker 2 in a very determined fashion, I would say.

Speaker 1 What is the main difference between him and Stalin in the sort of political maneuvering sense? Because all of this sounds very similar to.

Speaker 2 Yeah, I would say early in their career, they're very similar. So outwardly, they're very low-key.

Speaker 2 You know, Stalin was the bureaucrat, very low-key, not flamboyant, not making loud speeches like Trotsky did.

Speaker 2 But low-key, getting things done, seen as a very reliable person.

Speaker 2 This was a reason why Stalin was chosen.

Speaker 2

As far as I know, I don't know that much about Stalin. Same thing with Xi Jinping.

So

Speaker 2 his father

Speaker 2 belonged to actually the liberal faction in the Chinese Communist Party. His father never offended that many people within the party.

Speaker 2 I mean, you know, everyone at a high level will have, you know, sort of screwed over somebody along the way, but his father was in the better category, let's say.

Speaker 2 And he himself was very low-key. While the other princelings were fighting for very good jobs in the capital city of Beijing or in Shanghai, Xi Jinping said, oh no, it's okay.

Speaker 2

I'll go down to the villages. I'll work in Hebei in a rural area.

Then Fujian, which was kind of a peripheral area.

Speaker 2 And then Zhejiang was slightly better, but still not Beijing or Shanghai. So he got out of the way of this political infighting.

Speaker 2 I think

Speaker 2 in a similar way that Stalin did. Early on, he did not confront people too much.

Speaker 2 But once he came to power, he he knew they both knew what it took to control the party which they govern over.

Speaker 2 Basically, you form a whole series of coalitions to get rid of your most threatening enemy at a given time.

Speaker 2 So for Xi Jinping, it was like, oh, well, you know, this guy, Zhou Yung Kang, who controlled the police forces and also the Ministry of State Security at the time, doing all this irregular things, being fabulously corrupt, he's a threat to the whole party.

Speaker 2 So he convinced Hu Jintao to join with him to purge Zhou Yung Kang, which was successful.

Speaker 2 You know, Stalin did the same thing, you know, to Trotsky. And then after the most threatening person is gone, you form another coalition to purge the next person and so on and so forth.

Speaker 2 So they both basically did that until they achieved absolute power within the party. Yeah, yeah.

Speaker 1 And if you read the Stalin biography, so many of the, in the early part,

Speaker 1 like half the people in the Polybier are later are going to end up in the Gulags, and then many of the people in the Polybier later have been to the Gulag.

Speaker 1 I wonder if there's a Trotsky

Speaker 1 analogous person in the story, somebody who was a flamboyant speechmaker.

Speaker 2

Yeah, Bo Shilai. Bo Shilai.

Bo Shilai. Yeah.

So he was one competitor with Xi Jinping. But because he was so high profile that he never had a chance to be the top leader of China.

Speaker 2 And then, of course, Xi Jinping made sure that he would fall.

Speaker 1 Right. And now he's in prison.

Speaker 2

And now he's in prison. Yeah, he's not alive.

His son is in Canada, actually.

Speaker 2 He's on Twitter now on X.

Speaker 1 I should reach out, honestly. He'd be interested in that.

Speaker 2 That would be really interesting, actually.

Speaker 1 Let's move on to another topic I know you've studied deeply, which is the local government debt situation. Sure.

Speaker 1 What is the newest era? What is your sense of the situation now?

Speaker 2 Yeah, it just keeps growing in absolute size because basically

Speaker 2 China is trying to tell the world that they don't have a high debt level, which at the central level, that is sort of the case. You know, it's still 60, 70% of GDP.

Speaker 2 But the reason why that is the case is because there are a lot of things the Chinese government would like to do. They push it down to the local level.

Speaker 2 But the authorization of local debt issuance is authorized by the central government.

Speaker 2 So, at the end of the day, is really the central government telling local governments, like, okay, you need to do this thing.

Speaker 2 I'm not going to give you money, but I will give you the authorization to issue even more debt. So, the debt level keeps going higher and higher.

Speaker 2 The one thing that has alleviated the cash flow pressure late last year was the central government authorized, again, the issuance of close to 10 trillion renminbi in special local debt to repay some of the higher interest-bearing debt of local governments.

Speaker 2

But that's an accounting exercise. It doesn't literally decrease local debt.

It just changes from higher yielding to lower yielding.

Speaker 2 Meanwhile, the overall size of local government debt in China, I would estimate, to be 120% of GDP to 140% of GDP. Whoa.

Speaker 1 That's a top the 60% that is owed by the central government, yeah.

Speaker 2 So total governmental debt is, yeah, it's you know, pushing 200.

Speaker 1 And the high-level way to understand what this debt was for,

Speaker 1 the debt in Western countries and other OECD countries is often because you owe money basically to pensioners. In this case,

Speaker 1 it was just that they built bridges.

Speaker 2 Yeah, they built all the high-speed rail, all the infrastructure, the beautiful infrastructure that you do see in China. And then more recently, industrial policies, right? So

Speaker 2 for example, if there's a new science park for AI, let's say, right? The land that they acquire, the infrastructure that's built is all built with borrowed money. Then there are these startups.

Speaker 2 And the startups are partially financed by some of these central level investment funds that you read about, industrial policies.

Speaker 2 But then actually the local government also have their own CEDAR funds, which uses borrowed money to finance some of these venture deals.

Speaker 1 For startups, is the fact that they can get cheap credit from banks more relevant? Is the fact that they can get loans from provincial funds more important?

Speaker 1 There's also these central government funds, the big fund, and so forth.

Speaker 1 Which is the bigger piece here?

Speaker 2 So, a lot of it depends on your social network and your connections.

Speaker 2 So, if you're a startup at Tsinghua University, you have access to private sector funds, but also some of the central government cedar funds, if it falls in the right category, you know, semiconductors, AI, et cetera, et cetera.

Speaker 2 But if you're at Liam Wenfeng, I don't know. So at Liam Feng, because it started out as a financial institution, so it was mainly sort of private sector money from financial investors.

Speaker 2 But there are other AI, especially sort of more hardware-driven initiatives in the provinces, which are seeded by local government funds.

Speaker 2 And the point about financial repression is that without financial repression, an investor in China can invest in Silicon Valley.

Speaker 2 They can go to Sequoia and invest money, but because of capital control, they cannot legally move more than $20,000 a year out of China. They have to find domestic investment.

Speaker 2 So as a result, many of them choose to invest in Chinese high-tech

Speaker 2 or they choose to put their money in the bank.

Speaker 2 So actually a lot of people just choose to put their money in the bank and then the state banking system is then financed to, they have the deposits with which to lend to local government cedar funds for industrial policies.

Speaker 1 Aaron Ross Powell, and the crucial thing here is that the banking sector is totally controlled by the state.

Speaker 1 So you're not getting a true rate of return based on what the productive value of investment is. It's literally like 1%.

Speaker 2 Yes, the deposit rate is 1%. Yeah.

Speaker 1 Which is, I mean, it's like an insanely low inflation.

Speaker 2 Inflation rate is very low in China, right?

Speaker 1 There's a couple of mixed-up questions I want to ask here.

Speaker 1 So you said, well, if there were no capital controls, these people might want to take their money and go invest in Silicon Valley.

Speaker 1 Very basic development economics would show you that if a country is less developed, they'll have higher rates of return. So people would want to invest.

Speaker 1 The Silicon Valley would want to invest in China.

Speaker 1 Why would getting rid of capital controls make capital go the other way?

Speaker 1 And this goes into other questions of why is it the case that the Chinese stock market has performed so badly, even though the economy has grown a lot? And then why is it the case that

Speaker 1 they have a current account surplus and they're basically accumulating T-bills? When the pattern you should see, obviously, is that

Speaker 1 they can earn much higher rates of return building productive things in China than accumulating 4% yield T-bills.

Speaker 2 Yeah. Well, so at the deepest level, I would say there is a deep fundamental difference between capitalism and socialism.

Speaker 2 And it sounds very

Speaker 2

philosophical, but I think this might help sort of your Gen Z listeners think about this. Because for socialism, they only care about output.

It's like, okay,

Speaker 2 whatever capacity we're thinking about, whether it's grain production or

Speaker 2 metal production or these days robotics, we just want more of it.

Speaker 2 So then the state can use the state banking system, which they control, to allocate a huge amount of capital to maximize the output of all these different things that they care about.

Speaker 2 But when you maximize the output, you don't necessarily make money doing that.

Speaker 2 Whereas capitalism wants to maximize profit, which is, you know, as you know, the difference between the cost of production and the amount that you can earn from selling the output.

Speaker 2 For socialism, they don't care about that.

Speaker 1 Aaron Powell, Jr.: But the companies aren't socialist, right? The companies are profitable.

Speaker 2 No, but because the financial system is socialist, they're forced into socialist-like behavior. You know, you can't go into a bank and say, look, I make robotics.

Speaker 2 This robot that I'm going to make is going to be highly profitable

Speaker 2

down the road, but I can only make like 10 of them. And then the bank would be like, well, this is BS.

I know a lot of startups don't make any money.

Speaker 2 But at some point, notionally, you have to start making money. Whereas the socialist banking system basically says, you know, even if you never make any money or hardly any money, that's okay.

Speaker 2 As long as the Chinese government tells us that this is a strategic sector, as long as you can prove to us you can actually produce the thing that we want you to produce.

Speaker 2 If you never ever make money doing that, that's perfectly fine.

Speaker 1 What is the sort of outer loop feedback?

Speaker 1 The thing which keeps the system disciplined here, there's private investors who care about actually earning a rate of return, and so they're only going to invest in companies which they think have a viable shot of

Speaker 1 becoming bigger, huge companies that can actually be at the frontier in technology. If these banks are not actually competing against real investors, and it's not their money.

Speaker 2 Exactly.

Speaker 1 But it seems like this is compatible with many of the world's

Speaker 1 leading companies being

Speaker 1 developed in the system. So how is it working?

Speaker 2 Well, so this is where the bureaucracy steps in, right? So it's like, well, how would a bank tell what's a good company and what's not a good company?

Speaker 2 So then there's a complicated system where the mischief, so let's say for robotics or for semiconductors,

Speaker 2 there is a sort of expert group group in mischief industry and

Speaker 2 informationalization, information technology that will assess all these different projects. So the banks will literally send them and say, okay, this company wants to borrow $10 million.

Speaker 2 Do they have real technology? Is this a good prospect?

Speaker 2 And some bureaucrat, supposedly with no financial stake in the company, they're completely neutral, supposedly, I say supposedly, because in reality, we've seen many cases of corruption,

Speaker 2 in conjunction with an expert panel who, again, with no any relationship with the company or with the bank, will sign off on these projects or reject these projects, get sent back to the bank and the bank says, okay, these bureaucrats say that your project is good.

Speaker 2 You're good to go. Here's $100 million.

Speaker 1 But it seems to work.

Speaker 2 Yeah, yeah.

Speaker 1 No, but doesn't this just belie the whole idea? It's like sanction planning isn't supposed to work, right?

Speaker 2 No, no, no.

Speaker 2 So there's a selection bias. We see and pay attention to the cases that work.

Speaker 2 And there there have been some fabulous success cases, which, by the way, does not include Xiaomi or BYD because those were mainly privately funded at the beginning.

Speaker 1 And CATL and DJI. Yeah, exactly.

Speaker 2 So the success cases actually are not that. I mean, but there are, you know, I'm sure I don't know the cases, but like there are, well, Huawei.

Speaker 2 So I would say like Huawei, it is, there was a lot of state funding along the way and so on and so forth.

Speaker 2 So you have success cases, but there are so many failed cases and billions and billions billions of dollars just thrown down a hole basically for the failed cases.

Speaker 2 In fact, for semiconductor, things got so bad that they had to arrest a whole bunch, dozens of people in the Ministry of Information or Industry and Information Technology who were in charge of approving these semiconductor deals.

Speaker 2 They all went to jail because they were in a deal where, you know, some companies submit a bogus project, they approved it, they got a part of the money, and so on and so forth.

Speaker 2

So it doesn't work very well. I mean, of course, you have fraudulent cases in the U.S.

also, all that kind of stuff, but the scale in China, the waste in China is a much larger scale phenomenon.

Speaker 1 Yeah, and it's all financed, as you say, with this financial repression, which is basically a tax on savers.

Speaker 1 And so, even though there's no meaningful income tax and just value-added tax and corporate income tax, if you factor in the currency devaluation, which is a tax on consumers, and then this financial repression, which is a tax on savers, it actually might be a meaningful

Speaker 1 decrease in the quality of life of an average person. Yeah.

Speaker 2 No, I mean, you definitely see it.

Speaker 2 Like, you know, for an economy that's been growing 5 plus percent for decades, by this time, you would expect, you know, pretty much the vast majority of the population in China having all the basic necessities, shelters, medical care, et cetera, et cetera.

Speaker 2 You don't see that. You know, a lot of migrant workers, they're barely getting by.

Speaker 2 The homelessness is increasingly a problem in China, especially with the labor market being so fickle these days.

Speaker 2 Elderly care is pretty abysmal, you know, very basic level, let's say, for a lot of people. Not for everyone.

Speaker 2 So some people get very good elderly care if they worked for the government or SOE previously.

Speaker 2 So you see a lot of problems that the Chinese government has overlooked. So this is why I'm saying they have a goal of making all Chinese people very happy and fulfilled.

Speaker 2 One part of it is being fulfilled, the technology part, but the other part of truly making people living a good life,

Speaker 2 they're not making as much progress as they should, I would say.

Speaker 1 And then just to close the loop on this, so

Speaker 1 I think sometimes

Speaker 1 we get impressed when we see, oh, they've got the Made in China 2025 and the NDRC and the MIIT and so forth have these

Speaker 1 very specific, you know, LiDAR needs to get to this point, and we need the EU V machines at this point, and so forth.

Speaker 1 But your claim is that that part of the system is actually dysfunctional, and in fact, the part that actually works is the 5% that is totally private.

Speaker 2 No, so the private sector stuff works a lot better. You have occasional successes from the state finance system.

Speaker 2 So I wouldn't say that there are no success cases, but I would say that for every success case you see,

Speaker 2 there are just maybe even over a dozen failed cases, which, you know, of course you have failed cases everywhere, you know, in VC,

Speaker 2 but the amount of money being wasted in the state financial system would be much larger. Aaron Powell,

Speaker 1 going back to the local government debt burden,

Speaker 1 there's a world where AI isn't a big deal, and there's a world where AI is a big deal.

Speaker 1 If we live in the world where AI truly causes

Speaker 1 huge uplift to economic growth and so forth, is it possible that this problem doesn't meaningfully harm China's ability to compete at the frontier? And here's why that might be the case.

Speaker 1 It seems like this problem is especially affecting poor provinces.

Speaker 1 Whereas

Speaker 1 you have the actual numbers, but are Shanghai and Guangdong in a good position with respect to their fiscal situation?

Speaker 1 And could they keep funding you know, top-end semiconductors, AI firms, data centers?

Speaker 1 And so China could still keep competing at the frontier in AI, even if the poorer provinces don't have the money to fund basic services and so forth.

Speaker 2 And in the long run,

Speaker 1 they get advanced AIs, and that's a big uplift to economic growth. And they can just grow their way out of this debt problem.

Speaker 2 Yeah, so we can talk about that. I'm a bit skeptical about that for the case of China.

Speaker 2 But yes, indeed, as you said, some places like Shanghai and Guangdong, they're still in relatively okay fiscal positions.

Speaker 2 But then there are other sort of wealthier provinces with a lot of debt, also. So, Drejiang province,

Speaker 2 which is where DeepSeek is located, actually,

Speaker 2 and also Alibaba and all these tech companies, they have a high debt load. But because they start from a pretty wealthy place, they can still service the debt without too much difficulty.

Speaker 2 But actually, a trade war is going to make it worse for Dejiang province because a lot of the manufacturing export firms are also in Dejiang.

Speaker 2 But nonetheless, the case of China is that basically the financial system is geared toward fulfilling the priorities of the party, i.e. the priorities of Xi Jinping.

Speaker 2 So even if they can't do anything else, they will do the things that Xi Jinping wants them to do.

Speaker 2 And AI apparently is one of the higher priorities for Xi Jinping because he's held multiple study sessions, he's had different Polyborn meetings and so on and so forth.

Speaker 2 And Ding Xi Xiang, who's one of his most trusted lieutenants, is in charge of it, etc.

Speaker 2 So I do expect a fair amount of resources being devoted to it, regardless of the situation in local debt. I mean, in fact, at the local level, things are so bad, but they just don't care, right?

Speaker 2 So there are civil servants, teachers who are not paid four or five months out of the year. And then you can say, well, how can you run a government like that? Wouldn't it just collapse?

Speaker 2 But then you have to look at the outside options. You know, for your teacher, for your very low-level bureaucrat, what option do you have? I mean, do you want to go back to delivering food to people?

Speaker 2 Or would you rather at least take six, seven months of civil service salary? At least you have health care. At least you can get your free lunch at your workplace cafeteria every day.

Speaker 2 People still choose to work for the Chinese government, even if that were the case.

Speaker 2 But a lot of the previously very generous fringe benefits and so on and so forth, that has all been cut down because of the local debt issue.

Speaker 2 But they're still pouring a lot of resources into national defense and AI and technology.

Speaker 1 Aaron Powell, and what would a solution at this point look like? Because if you've already spent all this money, first of all, actually, why is it the case that these investments aren't productive?

Speaker 1 Because

Speaker 1 it's not like it's entitlement spending where you're doing it for,

Speaker 1 I don't know, old people, but then at the end of the day, you're not getting any return for it. Theoretically, these are like, you're building real bridges, you're building airports.

Speaker 1 So why aren't they productive? And then what does a solution at this point look like?

Speaker 2 Well, so it was very very productive. You know, I mean, I think you noted in this Art Kroeber book review that you did in the 1980s and 1990s because China lacked a lot of infrastructure.

Speaker 2 But once you built the first high-speed rail between Beijing and Shanghai, you built the second one, you built the third one, you know, there's very rapidly diminishing return.

Speaker 2 Also, as you know, the population is basically shrinking in China,

Speaker 2 and especially in a lot of cities in northeastern China and also in southwestern

Speaker 2 So you really don't need high-speed rails connecting those cities to other places in China because nobody lives there anymore.

Speaker 1 You can ask about this. So if the reason that the provincial leaders kept doing this

Speaker 1 construction was because they want to get promoted

Speaker 1 and they want to get

Speaker 1 GDP numbers on the book and government spending now is adds to GDP, even if the ultimate thing you're building is not that productive. But then the central government

Speaker 1

has had a problem with this for a while. And then they think this is fake.

They don't want to keep this fake growth going. And they see the local debt numbers.

Speaker 2 Were they still promoted nonetheless?

Speaker 1 Like, why, why did they, why were people doing this?

Speaker 1 Who was the person who created?

Speaker 1 And also, a lot of these people got arrested in the aftermath, right? So they weren't promoted. They were actually arrested.

Speaker 1 So, what was incentivizing them to keep.

Speaker 2 So when you invest in a large infrastructure project, a lot of money changes hand.

Speaker 2 And that is so, well, so this is a big debate in my field also. You know, some people are like, well, look, you know, like the more you invest, the more likely you're to get promoted.

Speaker 2 My argument is that it's not the actual investment,

Speaker 2 it's the rent-seeking that comes along with the investment, right? So, you know, you have to get a contractor for cement, you have to get a contractor for this and that,

Speaker 2 you know, you get a big envelope under the table, you know, as a kickback. Then that allows you to pay your superiors.

Speaker 2 You know, because you, let's say you did a billion-dollar investment to build light rail or something like that in a city, you got a hundred million dollar payout from all the contractors, you can give your superior $50 million

Speaker 2 to thank that person and to up your chance of getting a promotion.

Speaker 2 And so I would say that's more the realistic mechanism for linking investment and promotion than like, oh, good job.

Speaker 2 You generated investment and GDP in this city. We're going to to reward you with a promotion.

Speaker 2 In fact, there's really good work by James Kung showing this.

Speaker 2 It's like basically, also like when you do a real estate deal, you can sell land cheaply to politically connected princelings, and then they will lobby on your behalf for your promotion.

Speaker 2 And statistically, there is an effect. So if you sell land cheaply to princelings, your chance of promotion goes up.

Speaker 1 I find it fascinating the fact that

Speaker 1 whether a corrupt political equilibrium leads to more construction or less construction, because the political equilibrium in America today is that, I don't know, California isn't the least corrupt

Speaker 1 state in the world country.

Speaker 1 But the political equilibrium is that

Speaker 1 the fact that there's so many different factions who get their hand into the pocket means that it's not that everybody's like, we need California Real to have one yesterday because I need my share of it.

Speaker 1

It's that, oh, I'm going to get a little consulting fee to slow this down by five years. And another person.

So it's quite interesting. And if you read

Speaker 1 the

Speaker 1 char biography of Robert Moses and you look at the strategies he employed, it actually is very similar to what you're mentioning here, where it's in every single faction's interest that a bridge that Robert Moses is working on gets done through some of the mechanisms you mentioned.

Speaker 1

For example, he would give the banks these discounted bonds. for this construction.

So the bank lobbyists were encouraged to keep the construction going.

Speaker 1 And he would give, obviously the unions wanted employment, so they'd want the construction to happen. Every single person at every stage was incentivized.

Speaker 1 So I find it interesting that China has maintained to

Speaker 1 keep a political equilibrium, which encourages too much building, whereas our political equilibrium is

Speaker 1 that

Speaker 1 it's discouraged.

Speaker 2 Aaron Powell, yeah, it is. So basically, all the regulations in the U.S., you know, environmental, this, and that,

Speaker 2 builds its own sort of stakeholders and lobbying group.

Speaker 2 And it is in the interest of these lobbying groups to prolong the process so that they can absorb a higher share of the rent.

Speaker 2 Whereas in China, because they have this command structure headed by the Chinese Communist Party, the secretary of the city or province can cut through all the red tape because he's the boss of all the regulators at the local, most of the regulators, let's say at the local level.

Speaker 2 So if he wants to do something, he can cut through all of it as long as he can benefit somehow himself.

Speaker 2 So I think that would be, I would say, that's a difference. Interesting.

Speaker 1

Yeah. Okay.

And then what would a solution to this problem look like?

Speaker 1 Because if it's 100% of GDP, yeah,

Speaker 2 so I would say, and of course the Chinese government will never ever in a million years do it in its current form, which is to reduce a lot of the other unnecessary spending, like national defense, like a lot of the industrial policies,

Speaker 2 and then use the savings to bolster domestic demand with welfare policies and to gradually

Speaker 2 decrease overall amount of local government debt.

Speaker 2 That I think is economically sound because it's like China already has the largest navy in the world. Why does it need a navy that's even bigger than the largest navy in the world?

Speaker 2

It doesn't need that. I mean it has more than enough for national defense.

It has some of the best jet fighters in the world already, some of the best missile systems.

Speaker 2 Like no one is going to invade China or come close to it.

Speaker 2 So they actually don't need it. I mean the tech race, I mean, I do, I'm somewhat sympathetic to China, you know, because now that there's US policies

Speaker 2 preventing Chinese companies from buying all the chips and AI, so it wants its own capacity, is spending a lot of money on it.

Speaker 2 So that part I'm somewhat sympathetic, but other aspects of industrial policies, you know, for some of the battery stuff, for

Speaker 2 solar power, et cetera, it can certainly reduce a lot of subsidies. It can increase taxes, actually,

Speaker 2 on many export-oriented firms, which is one of the reasons why there's a big trade surplus in China and trade imbalance between the U.S. and China.

Speaker 2 Get more revenue that way to finance domestic demand and to pay down local government debt over time.

Speaker 2 The Chinese government, of course, will never do that because it has a very high places a very high priority over competition with the U.S. across many different fronts

Speaker 2

and to get dominance over multiple supply chains. But in the world of global trade, why do you need that? I mean, the same thing goes for the U.S.

The U.S.

Speaker 2 doesn't need dominance over every single supply chain. Yeah.

Speaker 1 Why is it the case that economists, so when they're talking about rebalancing more towards consumption, they'll often suggest that you should do increase the amount of welfare.

Speaker 1 But it seems like the more straightforward thing to do would just be to

Speaker 1

get rid of financial repression so that by default savers would have more purchasing power, get rid of currency devaluation. Again, the same effect.

So

Speaker 1 why not get rid of the regressive taxes rather than the law?

Speaker 2 Because

Speaker 2 yeah, if you just get rid of financial repression, it will only benefit the savers, which is

Speaker 2 10% of households, net savers, 10%, 20% of households. If you look at median households, they have very little savings actually, besides the home in which they live.

Speaker 2

Yeah, so there's this misconception. It's like, oh, China has like the largest savings deposit in the world.

And that's true.

Speaker 2 But if you look at the distribution of the savings deposits, it's highly concentrated in the hands of 10%. So even if you say, oh, okay,

Speaker 2 deposit interest rate suddenly goes up to 4%, it's only going to benefit the people with a large amount of savings. Most people, they're not going to benefit from it.

Speaker 2 Most people, if they don't have better welfare services, they're going to save like crazy in anticipation of getting sick. So you do need better,

Speaker 2 certainly medical care insurance in China.

Speaker 2 I mean, that's something, you know, frankly, I worry about the U.S.