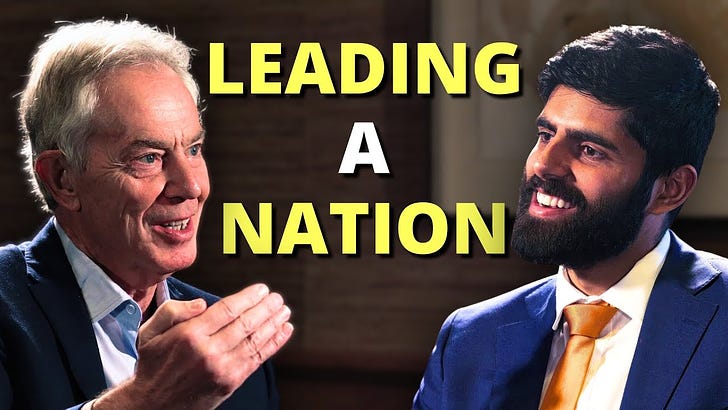

Tony Blair - Life of a PM, The Deep State, Lee Kuan Yew, & AI's 1914 Moment

I chatted with Tony Blair about:

- What he learned from Lee Kuan Yew

- Intelligence agencies track record on Iraq & Ukraine

- What he tells the dozens of world leaders who come seek advice from him

- How much of a PM’s time is actually spent governing

- What will AI’s July 1914 moment look like from inside the Cabinet?

Enjoy!

Watch the video on YouTube. Read the full transcript here.

Follow me on Twitter for updates on future episodes.

Sponsors

- Prelude Security is the world’s leading cyber threat management automation platform. Prelude Detect quickly transforms threat intelligence into validated protections so organizations can know with certainty that their defenses will protect them against the latest threats. Prelude is backed by Sequoia Capital, Insight Partners, The MITRE Corporation, CrowdStrike, and other leading investors. Learn more here.

- This episode is brought to you by Stripe, financial infrastructure for the internet. Millions of companies from Anthropic to Amazon use Stripe to accept payments, automate financial processes and grow their revenue.

If you’re interested in advertising on the podcast, check out this page.

Timestamps

(00:00:00) – A prime minister’s constraints

(00:04:12) – CEOs vs. politicians

(00:10:31) – COVID, AI, & how government deals with crisis

(00:21:24) – Learning from Lee Kuan Yew

(00:27:37) – Foreign policy & intelligence

(00:31:12) – How much leadership actually matters

(00:35:34) – Private vs. public tech

(00:39:14) – Advising global leaders

(00:46:45) – The unipolar moment in the 90s

Get full access to Dwarkesh Podcast at www.dwarkesh.com/subscribe

Press play and read along

Transcript

Speaker 1 Today I have the pleasure of speaking with Tony Blair, who was of course Prime Minister of the UK from 1997 to 2007 and now leads the Tony Blair Institute, which advises dozens of governments on improving governance, reform, adding technology.

Speaker 1 My first question, I want to go back to your time in office. And when you first got in, you had these large majorities.

Speaker 1 What are the constraints on a prime minister despite the fact that they have these large majorities? Is it the other members of your party you're fighting against you? Is it the deep state?

Speaker 1 Like what part is constraining you at that point?

Speaker 2 The biggest constraint is that politics and in particular political leaderships, probably the

Speaker 2 only walk of life in which

Speaker 2 someone is put into an immensely powerful and important position with absolutely zero qualifications or experience. I mean, I never had a ministerial appointment before.

Speaker 2 My one and only was being prime minister, which, you know, it's great if you want to start at the top, but

Speaker 2 it's that that's most difficult. So you come in,

Speaker 2 and you're often, you often come in as when you're running for office, you have to be the great persuader. The moment you get into office, you really have to be the great chief executive.

Speaker 2 And those two skill sets are completely different. And a lot of political leaders fail because they've failed to make the transition.

Speaker 2 And

Speaker 2 you know, those executive skills, which are about focus, prioritization, good policy, building the right team of people who can actually help you govern.

Speaker 2 Because the moment you become the government, you end up

Speaker 2 leaving aside the saying becomes less important than the doing. Whereas when you're in opposition, you're running for office, or it's all about saying.

Speaker 2 So all of these things mean that it's a much more

Speaker 2 difficult, much more focused. And

Speaker 2 it's suddenly you're thrust into this completely new environment when you come in. And that's what makes it, that's the hardest thing.

Speaker 2 And then, of course, you know, you do have a situation in which the system as a system,

Speaker 2 it's not that it's a

Speaker 2 believer that there's this great deep state theory. We can talk about that, but that's not the problem with government.

Speaker 2

The problem with government is that it's not a conspiracy, either left-wing or right-wing. It's a conspiracy for inertia.

The thing about government systems is that they always think we're permanent.

Speaker 2

You've come in as the elected politician. You're temporary.

And,

Speaker 2

you know, we know how to do this. And if you only just let us alone, we would carry on managing the status quo in the right way.

Yeah.

Speaker 2 And so that's the toughest thing. It's making that transition.

Speaker 1

Okay. So that's really interesting.

Now, if we take you back everything you knew, let's say in 2007, but you have the majorities and maybe the popularity you had in 1997.

Speaker 1 What fundamentally, you said you have these executive skills now. What fundamentally is it that you know what a time waste, what kinds of things are time waster?

Speaker 1

So you say, I'm not going to do these PMQs. They're total theatrics.

I'm not going to, you know, I'm not going to meet the queen or something.

Speaker 1 Is it the time? Is it that you're going to go against the bureaucracy and say, I think you're wrong about your inertia? What fundamentally changes?

Speaker 2 Well, it wouldn't be that you wouldn't do Prime Minister's question because Parliament will insist on that. And you certainly wouldn't want to offend, well, it was the Queen

Speaker 2

in my time. No, but you're right.

What you would do is have a much clearer idea of how to give direction to the bureaucracy and how to bring in outside skilled people who can help you deliver change.

Speaker 2 And so, you know, I always split my premiership into the first five years, which in some ways were

Speaker 2

the easiest. We were doing things that were important, like a minimum wage.

We did big devolution. We did the Good Friday Peace Agreement in Northern Ireland.

Speaker 2 But it was only really in the second half of my premiership that we started to reform healthcare, education, criminal justice. And those systemic reforms require, that's when

Speaker 2 your skill set as a chief executive really comes into play.

Speaker 1 There's a perception that many people have that if you could get a successful CEO or business person into office, these executive skills would actually transfer over pretty well into becoming a head of state.

Speaker 1 Is that true? And if not,

Speaker 1 what is it that they'd be lacking that you need to be an electable leader?

Speaker 2

Yeah, so this is really interesting. And I think a lot about this.

The truth is, those skills would transfer to being a political leader,

Speaker 2 but they're not the only skills you need because you still got to be a political leader.

Speaker 2 And therefore, you've got to know how to manage your party. You've got to know how you frame certain things.

Speaker 2 You've got to know, frankly, as a CEO of a company, you're the person in charge, right? You can more or less lay down the law, right? Politics is more complicated than that. So,

Speaker 2 when you get highly skilled CEOs come into politics,

Speaker 2 oftentimes they don't succeed, but that's not because their executive skill set is the problem. It's because they haven't developed a political skill set.

Speaker 1 Interesting.

Speaker 1 I was reading your memoir, and one thing I thought was interesting is there were a couple of times you said that you realized later on that you had more leverage or you were able to do things in retrospect that you didn't do at the time.

Speaker 1 And

Speaker 1 is that one of the things that would change? And like if you go back to 1997, you realize I actually can can fire this entire team if I don't think they're doing a good job.

Speaker 1 I actually can cancel my meetings with ambassadors. How much of that would be? Like, did you have more leverage than you realized at the time?

Speaker 2 Well, in terms of running the system, yes.

Speaker 2

Definitely with the benefit of experience. I would have given much clearer directions.

I would have moved people much faster. I would have probably done...

Speaker 2 You know, because in politics, again, this is where it's different from running a company.

Speaker 2 In a company, by and large, right, you can put the people in the places you want them right and they're you know except in exceptional circumstances i think this is true except in exceptional circumstances if you're running a company

Speaker 2 you know you've got no one in the senior management who you don't want to be in the senior management right

Speaker 2 politics isn't like that because you've got you've you've got elements, political elements you may have to pacify. There may be people that you don't particularly want because they're not maybe

Speaker 2 not particularly good good at being ministers, but they may be very good at managing your party or your government in order to get things through.

Speaker 2 And what I learned over time is the important thing is to put in to the core positions that really matter to you. You can't don't fall short on quality.

Speaker 2 And, you know, it's something, it's one of the really interesting things, you know, because I think being a political leader is the same as leading a company or a community center or a,

Speaker 2 you know, or a football team. It's all all comes to the same thing, but you realize it's such an obvious thing to say that it's all about the people, but it's all about the people.

Speaker 2 If you get really good, strong, determined people who are prepared to, who share your vision and are prepared to get behind and really push, then

Speaker 2 you don't need that many of them actually to change a country, but they do need to be there.

Speaker 1 That's really interesting.

Speaker 1 So when I think about, this is not particular even to the UK, but even in Western governments, people are often frustrated that they elect somebody they think is a change maker.

Speaker 1

Things don't necessarily change that much. The system feels an inertia.

If this is the case, is it because they didn't have the right team around them?

Speaker 1 Because if you think of like, I don't know, Obama or Trump or Biden, at the very top, I assume they can recruit like top people to the extent that they weren't able to exact the change they wanted.

Speaker 1 Is it because, well, you know,

Speaker 1 must not have been because they didn't get the right chief of staff, right? They can probably get the right chief of staff.

Speaker 2 You know, absolutely. And they can get really good people.

Speaker 2 And, you know, one of the things you actually learn about being at the top of a government is, you know, pretty much if you pick up the phone to someone and say, I need you to come and to help, that they will come.

Speaker 2 I think the problem's not that. The problem is that

Speaker 2 Number one, and I say this often to the leaders that I work with, because, you know, we work in roughly 40 different countries in the world today, and

Speaker 2

that's only growing. And we have teams of people that go and live and work alongside the president's team.

And I kind of talk and exchange views with the president or the prime minister.

Speaker 2

And very often the two problems are these. Number one, people confuse ambitions with policies.

Right. So often I will speak to a leader and I say, so what are your policies?

Speaker 2 And he'll give me a list of things.

Speaker 2

And they actually, I say to them, those aren't really policies. They're just ambitions.

And ambitions in politics are very easy to have because they're just general expressions of good intention.

Speaker 2 The problem comes with the second challenge, which is that though politics at one level is very crude, right?

Speaker 2 You're shaking hands, kissing babies, making speeches, devising slogans, attacking your opponents, right? That's quite a crude business.

Speaker 2 When it comes to policy, it's a really intellectual business politics. And that's why, you know, people often, if they've only got ambitions,

Speaker 2

then they haven't really undertaken the intellectual exercise to turn those into policies. And policies are hard.

You know, it's hard to work out what the right policy is.

Speaker 2 If you take this, you know, AI revolution, and I think we're living through a period of massive change, right? This is the biggest technological change since the Industrial Revolution, for sure.

Speaker 2 For political leaders today to understand that, to work out what the right policy is, to access the opportunities, mitigate the risks, regulate it. This is really difficult work.

Speaker 2 And so what happens a lot of the time is that people are elected on the basis they are change makers because they've articulated a general vision for change.

Speaker 2 But when you then come to, okay, what does that really mean in specific terms? That's where the hard work hasn't been done.

Speaker 2 And if you don't do that hard work and really dig deep, then you, you know, what you end up with, as I say, are just their ambitions and they just remain ambitions.

Speaker 1 Okay, so now that you brought up AI, I want to ask about this. I do a lot of

Speaker 1 episodes on AI. And to the people who are in the industry, it seems plausible, though potentially unlikely, that in the next few years, you could have

Speaker 1 a huge sort of July 1914 type moment. But for AI, there's a big crisis, something major has happened in terms of misuse or a warning shot.

Speaker 1 Today's governments, given how they function, either in the West or how you see them function with the other leaders you advise, how well would they deal with this?

Speaker 1 Like, so they get this news about some AI that's escaped or some bioweapon that's been made because of AI. Would it immediately kick off sort of a race dynamic from the West to China?

Speaker 1 Do they have the technical competence to deal with this? How would that shape out?

Speaker 2 Right now, definitely not.

Speaker 2 And one of the things that we do as an institute, one of the reasons I'm here actually

Speaker 2 in Silicon Valley is to try and

Speaker 2 bridge the gap between what I call the change makers and the policymakers.

Speaker 2 Because the policymakers, a lot of the time, just fear the change makers, and the change makers, a lot of the time, don't want really anything to do with the policymakers because they just think they get in the way.

Speaker 2 Okay, so you don't have a dialogue, but if

Speaker 2 what you're describing to a case were to happen, and by the way, I think it's possible at some point it does happen.

Speaker 2 If it happened right now, I think political leaders wouldn't have the

Speaker 2 they wouldn't know where to begin in solving that problem or what it might mean.

Speaker 2 So I think this is why I keep saying to the political leaders I'm talking to today, and we're likely to have a change of government

Speaker 2 in the UK

Speaker 2 this year. And I am constantly saying to my own party, Led Party, which will probably win this election,

Speaker 2 you've got to focus on this technology revolution.

Speaker 2 It's not an afterthought. It's the single biggest thing that's happening in the world today of a real world nature that is going to change everything.

Speaker 2 Leave aside all the geopolitics and the conflicts and war and America, China, all the rest of it.

Speaker 2 This revolution is going to change everything about our society, our economy, the way we live, the way we interact with each other.

Speaker 2 And if you don't get across it, then when there is a crisis like the one you're positing could happen,

Speaker 2 you're going to find you've got no idea how to deal with it.

Speaker 1

Yeah. Okay.

So I think COVID is maybe a good case study to analyze how these systems function.

Speaker 1 And Tony Blair Institute Institute made, I think, what were very sensible recommendations to governments, many of which went unheeded.

Speaker 1 And what I thought was especially alarming about COVID was not only that governments made these mistakes with vaccine rollout and testing and so forth, but that these mistakes were so correlated across major governments.

Speaker 1

No Western government basically got COVID right. Maybe no government got COVID right.

What is the fundamental source of that correlation in the way that governments are bad at dealing with crises?

Speaker 1 they seem in some correlated way bad with crises is it because the same people are running these governments is it because the regular the apparatus is the same why why is that well first of all to be fair to people who who were in government at the time of covert it's it's a it was a difficult thing to deal with

Speaker 2 you know i said the problem with covert was it it was plainly more serious than your average flu but it wasn't the bubonic play right so

Speaker 2 to begin with there was one very difficult question which is to what degree do you try and shut the place down in order to get rid of the disease, right? And you had various approaches to that.

Speaker 2 But that's one very difficult question. And most governments

Speaker 2 kind of try to strike a middle course, right? To do restrictions, but then ease them up over time.

Speaker 2

And then you have the issue of vaccination. Now, normally with drugs, it takes you years to trial a drug, right? You had to accelerate all of that.

And that was done, to be fair.

Speaker 2 But then you have to distribute it.

Speaker 2 And that is also a major challenge. So

Speaker 2 I think part of the problem was that governments weren't sure where to go to for advice.

Speaker 2 You know, they had scientific advice, they had medical advice, but then they had to balance that with the needs of their economy.

Speaker 2 And the anxiety a lot of people had that when they that you were having a large shutdown, that they were going to be hugely disadvantaged, as indeed people were.

Speaker 2 And I think one of the things things that COVID did was

Speaker 2 for the developing world,

Speaker 2 I think there's an argument for saying for the developing world that lockdowns probably did more harm than good.

Speaker 1 Right.

Speaker 1 But so it's, it sounds like you're saying that they made the trade-off, which you're describing in the wrong way, where they could have gone heavier on the testing and vaccination rollout so that the lockdowns could have been avoided and fundamentally more lives could have been saved.

Speaker 1 I still don't understand. So, I mean, in some fundamental sense, the pandemic is a simpler problem to deal with than an AI crisis in a technical sense.

Speaker 1 Like, yes, you had to fast-track the vaccines, but it's a thing we've developed before, right? There's vaccines, you roll them out.

Speaker 1 If the government can't get that right, how worried should we be about their ability to deal with AI risk? And should we then just be fundamentally averse to a government-led answer to the solution?

Speaker 1 Should we hope the private sector can solve this because the government was so bad at COVID?

Speaker 2 Well, what the private sector can do is to input into the public sector.

Speaker 2 And so, you know, in COVID, I mean, the countries that handed vaccine procurement, well, not so much vaccine procurement, vaccine production, if they handed it to the private sector and said, run with it, right?

Speaker 2 Those are the countries that did best, frankly.

Speaker 2 And

Speaker 2 I think, especially with something as technically complex as AI, you know, you are going to rely on the private sector for

Speaker 2 the facts of what is happening and to be able to establish the options about what you do. But in the end,

Speaker 2 the government or the public sector will have to decide which option to take.

Speaker 2 And the thing that makes governing difficult is I always say to people, when you decide, you divide.

Speaker 2

You know, the moment you take a decision on a public policy question, there are always two ways you can go. Right.

With COVID, you could have decided to do what Sweden did and let the disease run,

Speaker 2 pretty much. You could have decided to do what China did and lock down down completely.

Speaker 2 But then what happened with China was once you got the Omicron variant and it became obvious you weren't going to be able to keep COVID out,

Speaker 2 they didn't have the facility or the agility to go and change policy. But, you know, these policy questions are hard.

Speaker 2 And it's very easy with hindsight, you know, to say, yeah, you should have done this, should have done that. But I think if this happened in relation to AI,

Speaker 2 you would absolutely depend on the people who were developing AI to be able to know what decision you should take.

Speaker 2 Not necessarily how you decide it, but what is the decision.

Speaker 1 Yeah. I still don't fundamentally understand the answer to, okay, so you had before COVID, we had these bureaucracies and we hope they function well, health bureaucracies, we hope they function well.

Speaker 1 It turns out many of them didn't.

Speaker 1 We probably have equivalents in terms of AI, where we have government departments that deal with technology and commerce and so so forth.

Speaker 1 And if they're as potentially broken as we found out that much of our health bureaucracy is,

Speaker 1 if you were prime minister now or the next government, what would you do other than we're going to have a task force, we're going to make sure we're making good decisions. But

Speaker 1 I'm sure like people were trying to make sure the CDC was functional and like it wasn't. Would you just like fire everybody there and like make a new department?

Speaker 1 How would you go about like making sure it's really ready for the AI crisis?

Speaker 2 Yeah. So

Speaker 2 I think you've got to distinguish between two separate things. One is

Speaker 2 making the system

Speaker 2 have the

Speaker 2 skills and the sensitivity to know the different contours of the crisis that you've got and to be able to produce potential solutions

Speaker 2 for what you do.

Speaker 2 We needed to rely upon the scientific community to say, this is how we think the disease is going to run. We relied on the private sector to say, this is how we could develop vaccines.

Speaker 2 We had to rely on different agencies in order to say, well, I think you could concertina the trial period to get the drugs.

Speaker 2 But in the end, the decision whether you lock down or you don't lock down, you can't really leave it to those people because that's not their.

Speaker 2 So you see what I mean?

Speaker 2 So in the end, as with AI,

Speaker 2 okay, if you look at it at the moment, so

Speaker 2 some people want to regulate AI now and regulate it on the basis that it's going to cause enormous dangers and problems, right?

Speaker 2 And because it's general purpose technology, yeah, there are real risks and problems associated with it. So Europe is already moving in quite a, you know, frankly, an adverse regulatory way.

Speaker 2 On the other hand, there would be people saying, well, if you do that, you're going to stifle innovation and we're going to lose the opportunities that come with this new technology.

Speaker 2 But balancing those two things, I mean, that's what politics is about. Now, you need the experts, the people who know what they're talking about to tell you,

Speaker 2

this is how AI is going to be. This is what it can do.

This is what it can't do. Okay,

Speaker 2 we are explaining the technicality to you, but ultimately what your policy is, you've got to decide that. And by the way, whichever way you decide it, someone's going to attack you for it.

Speaker 1

Look, I'm incredibly grateful that I've been able to turn this podcast into an actual business. And one of the reasons why is Stripe.

Stripe is how I set myself up in LLC.

Speaker 1

It's what I use to send invoices to my sponsors and get paid by them. And I'm not the only one.

Millions of businesses use Stripe to accept payments and move money around the world.

Speaker 1 That includes small businesses and startups like mine, where we're just trying to build our product instead of worrying about the hassle of the payment rails.

Speaker 1 But it also includes big businesses like Amazon and Hertz. These guys have unlimited engineers that they could throw at this problem, but they prefer to have Stripe build payments for them.

Speaker 1 And that's because Stripe can fine-tune the details of the payment experience across billions of transactions and then serve what works best for yours.

Speaker 1 That obviously means higher conversion rates and as a result, more revenue for you.

Speaker 1

So, thanks to Stripe for sponsoring this episode and also for making it possible for me to earn a living doing what I love. And now, back to Tony Blair.

Okay, so let's go back to

Speaker 1 the topics we discussed with foreign leaders at TBI.

Speaker 1 If you were,

Speaker 1 you know, take Lee Kuan Yew and his position in the 1960s and the Singapore he inherited.

Speaker 1 If you were advising Lee Kuan Yew in the 60s with the advice you would likely give to a developing country now, would Singapore have been even more successful than it ended up?

Speaker 1 Would it have been less successful? What would the effect of your advice now have been on Singapore in the 60s?

Speaker 2 With Lee Kuan Yew in Singapore,

Speaker 2 I mean, it's the wrong way around. I mean,

Speaker 2 I learned so much from him.

Speaker 2 And I went to see him first back in the 1990s when I was leader of the Labour Party. And I went to

Speaker 2

see him in Singapore. And the Labour Party had been really critical of Singapore.

And so the first thing he said to me when I came in the room was, why are you seeing me?

Speaker 2

You know, your party's always hated me. And so I said, I want to see you because I've watched what you do in government.

I want to learn from it.

Speaker 2 So I don't think there's anything I could have told Lee Kuan Yu. But the interesting thing, because he's a fascinating leader.

Speaker 2 And

Speaker 2 this is so interesting about government and why

Speaker 2 what I say is that you can can look upon government like don't look upon it as a branch of politics look upon it as its own discipline professional discipline and you can learn lessons of what's worked and what doesn't work and so the fascinating thing about Lee Kuan Yew is he took three decisions really three important decisions right at the beginning for Singapore.

Speaker 2

Each one of them now seems obvious. Each one at the time was deeply contested.

Number one,

Speaker 2 he said, everyone's going to speak English in Singapore. Now, there were lots of people who said to him at the time, no, no, we've been thrown out of Malaysia effectively.

Speaker 2

We're now a fledgling country, a city-state country. We need to have our own local language.

You know, we need to be true to our roots and everything.

Speaker 2

He said, no, English is the language of the world, and we're all going to speak English. But that's what happens in Singapore.

Secondly, he said,

Speaker 2 we're going to get the best intellectual capital and management capital from wherever it exists in the world, and we're going to bring it to Singapore.

Speaker 2 And again, people said, no, we should stand on our own two feet.

Speaker 2 And you're also bringing in the British who we just, you know, who we've got all these disputes with.

Speaker 2 And he said, no, I'm going to bring in the best from wherever they are, and they're going to come to Singapore. Today, Singapore exports intellectual capital.

Speaker 2 And the third thing he did was he said, there's going to be no corruption.

Speaker 2 And one of the ways we're going to do that is we're going to make sure our political leaders are well paid, which the Singapore leaders are the best paid in the world by a factor of about 10 for

Speaker 2 the next person.

Speaker 2 And there's going to be zero tolerance of corruption, zero tolerance of corruption. And those are the three decisions that were instrumental in building Singapore today.

Speaker 1 To the extent that Western governments have,

Speaker 1 you know, you could go to the UK right now or the US and fundamentally, if you had to narrow down the list of the three key priorities and what would somebody who is empowered to do so, what could they do to fix that?

Speaker 1 Do Western leaders, if Starmer is elected in the UK or whoever becomes president in the U.S.,

Speaker 1 would they have the power to enact what the equivalent would be for their societies right now?

Speaker 1 Or is it just sort of like

Speaker 1 you have all this inertia? You can't start fresh. I think it worked start in the 60s.

Speaker 2

No, you definitely can. I mean, the American system is different because it's a federal system.

And there's probably

Speaker 2 in many ways it's a good thing that there are limits to what what the federal government can do in the US.

Speaker 2 But if you take the UK or most governments where there's a lot of power at the center, I mean,

Speaker 2 what we've just been talking about, which is the technology revolution, how do you use it to transform healthcare, education, the way government functions? How do you help educate

Speaker 2 the private sector as to how they can embrace AI in order to improve productivity? I mean, this is a huge agenda for a government and a really exciting one.

Speaker 2 I mean, I keep saying to people that we're in politics today, because sometimes they get a bit, you know, people get a bit depressed about being in politics because you get all this criticism.

Speaker 2 People certainly in the West feel society is not changing fast enough and well enough.

Speaker 2 And I say, no, it's a really exciting time to be in politics because you've got this massive revolution that you've got to come to terms with.

Speaker 1 Speaking of federalism, do you worry that so you advise these dozens of governments? And for any one leader, you're probably giving very sensible advice.

Speaker 1 For their country, it's positive expected value.

Speaker 1 But to the extent that that limits the variance and experimentation across countries of different ways to govern or different policies, are we losing the ability to discover a new Singapore?

Speaker 1 Because there's,

Speaker 1 you know, Western NGOs or whatever global institutions we have, we will give you good recommendations and maybe there's like some missing thing we don't understand that an experimentation would reveal.

Speaker 2 Yeah, so we really don't do that with our governments because, by the the way, one of the things governments should be able to do is experiment to a degree.

Speaker 2 And part of the problem with systems is there's always a bias towards caution. That's what I mean by saying the systems, if they're a conspiracy for anything, it's for inertia.

Speaker 2

But there are some things. So what we do, we concentrate with governments on what are true no matter what government you're in.

So I describe four P's of

Speaker 2 government when you get into power, right? Number one, you've got to prioritize because if you try to do everything, you'll do nothing.

Speaker 2 number two you've got to get the right policy what we were talking about before you know and that means going deep and getting the right answer and that means often bringing people in from the outside who can tell you what the right answer is which has nothing to do with left right it's usually to do with practicality number three you've got to have the right personnel and number four you've got to performance manage you know once you've decided something and you've got a policy you've got to focus on the implementation now whether you're running the united states of america you're running you know a small African country.

Speaker 2 Those things are always true.

Speaker 1 Okay, let's talk about foreign policy for a second.

Speaker 1 This is not just you, but every sort of administration has to deal, especially Western administration, that to deal with these irascible dictatorial regimes.

Speaker 1

And they're like right on the brink of WMDs, and they make all these demands in order to... put off their path towards WMDs.

Obviously, you had to deal with Saddam.

Speaker 1

Today we have to deal with Iran and North Korea. It seems like sanctions don't seem to work.

Regime change is really expensive.

Speaker 1 Is there any fundamental solution to this kind of dilemma that we keep being put into decade after decade? Can we just buy them a nice mansion in Costa Rica?

Speaker 1 Or what can we do about these kinds of regimes? Yeah,

Speaker 2 it's very difficult.

Speaker 2 I think you can do. I mean, if you take Iran today,

Speaker 2 I don't think there's any appetite in the West, certainly, to go and enforce regime change.

Speaker 2 But I think you could do two things that are really important, because Iran is basically the

Speaker 2 origin of most of the destabilization across the Middle East region and beyond.

Speaker 2 First of all, you can constrain it as much as possible. And secondly, you can build alliances.

Speaker 2 which mean that their ability to impact is reduced. But But

Speaker 2 it's a constant problem because, you know,

Speaker 2

they're determined to acquire nuclear weapons capability. We want to stop them doing that.

We don't want to engage in regime change.

Speaker 2

On the other hand, all the other things that you do will be limited in their effect. So it's difficult.

It's very difficult, particularly now where you have an alliance that has grown up.

Speaker 2 where China, Russia, Iran, to a degree, North Korea work closely together.

Speaker 1 As a leader, how do you distinguish cases when the intelligence communities come to you and

Speaker 1 say, well, how do you distinguish a case like Iraq, where potentially they got it wrong versus Ukraine, where it seems like they were on the ball? How do you know which intelligence to trust?

Speaker 1 And how good is Western intelligence generally? How good are the five I's?

Speaker 2 Generally, it's extremely good, and the five I's is extremely good.

Speaker 1 And then how do you distinguish the cases where they're not?

Speaker 2 Well,

Speaker 2 it's difficult.

Speaker 2 And with the experience, you know, the benefit of hindsight, particularly in relation to Iraq, you've got to go much deeper and you've got to not take the fact that there was all these problems in the past as an indication of what's happening now,

Speaker 2 or in the future. But I think on the whole, Western intelligence is reasonably good and of course will get much better now with the tools it's got at its disposal.

Speaker 1 How much situational awareness do they have about the topics you're talking about, whether it's AI or the next pandemic,

Speaker 1 these forward-looking kinds of problems rather than who's doing an invasion when, which maybe they have a lot of expertise and decades of experience with, but like predicting who's got the data center where and so those kinds of things, how could they adapt?

Speaker 2 I think they're all over this stuff now. The intelligence services here in America, in the UK,

Speaker 2 yeah, no, it's, it's a,

Speaker 2 but you also got a whole new category of of threat to deal with because the cyber threats are real and you know potentially devastating in their impact. And

Speaker 2 you can see from Ukraine, I mean, war is going to be fought in a completely different way in the future as well.

Speaker 1 When you look at the different leaders you're advising, and maybe just through your experience talking to them while you were in office and seeing how their countries progressed, how much of the variance in outcomes of countries is explained by the quality of the leadership versus other endogenous factors, human capital, geography, whatever else?

Speaker 2 Right. So I think, I mean, the whole reason I started this institute was

Speaker 2 because I think think the quality of governance, of which the leadership is a big part, I think it is the determinant.

Speaker 2 In today's world, where capital is mobile, technology is mobile,

Speaker 2 any country with good leadership,

Speaker 2 it can make a success. And, you know, if

Speaker 2 you can take two countries side by side,

Speaker 2 same resources, same opportunities, same potential, therefore, one succeeds, one fails. If you look at it, it, it's always about the quality of decision-making.

Speaker 2 So, if you take, for example, before the Ukraine war, if you take Poland and Ukraine, when both came out of the Soviet Union in the early 1990s,

Speaker 2 I think people would have given Ukraine as much chance as Poland of doing well. Poland today is doing really well.

Speaker 2

Right. Why is that? Because they joined the European Union.

They've had to make huge changes and reforms. And therefore, they're a successful country.

You look at Rwanda and Burundi.

Speaker 2 It was Rwanda that suffered the genocide. But Rwanda today, I mean, it's one of the most respected countries in Africa.

Speaker 2 So, and then you look at the Korean Peninsula, which is the biggest experiment in human governance there's ever been, North Korea and South Korea.

Speaker 2 South Korea, South Korea had the same GDP per head as Sierra Leone in the 1960s. And now it's one of the top countries.

Speaker 1 And you think that's fundamentally a question of who the leadership was, like Park and South Korea? Or there are other factors that are obviously different between these countries, right?

Speaker 1 And also, you mentioned

Speaker 1 leadership determines governance, but I guess in the,

Speaker 1 if you look at a system like the United States or the UK, we've had good and bad leaders. Fundamentally, the quality of the governance doesn't seem to shift that much between who the leader is.

Speaker 1 Is the quality of governance sort of and the quality of the institutions a sort of separate endogenous variable from the leadership?

Speaker 2 Well, the institutions matter and good leaders should be able to build good institutions. But, you know, we were talking about Lee Kuan Yu in Singapore.

Speaker 2 Would Singapore have be Singapore without those decisions that he took? No.

Speaker 2 And

Speaker 2 if you look at the

Speaker 2 take, for example, China and Deng Xiaoping.

Speaker 2 I mean, when he decided to switch after the death of Mao and switch policy completely to open China up, that China opening up, I mean, that made the difference.

Speaker 2 If you look, if you track back India's development over the past 25 years, you can see the points at which which decisions were taken that

Speaker 2 gave India the chance it has today. So

Speaker 2 I actually think the interesting thing about this

Speaker 2 is

Speaker 2 how much it really does matter who the leader is and

Speaker 2 the governance of the country. And I think the interesting thing today,

Speaker 2 which is what I say to people engaged in this groundbreaking revolution of artificial intelligence, is we need your help in changing government and changing countries.

Speaker 2 Because we could do things, what I say when I'm in talking to people in the developing world today and leaders that we're working with, I say to them, don't try and replicate the systems of the West.

Speaker 2 You don't need to do that.

Speaker 2 You can teach your children better and differently without building the same type of system we have in the West.

Speaker 2 I wouldn't design the healthcare system in the UK today as it is now if we had the benefit of generative AI.

Speaker 2 So this is the leaders that are going to succeed in these next years will be the people that can understand what is happening in places like this.

Speaker 2 And the frustrating thing from our perspective, from the perspective of leaders, is that there's very few people in the technology sector who really, even though they would be probably very well-intentioned towards the developing world, they sort of think, well, I don't know what I can do in order to help.

Speaker 2 But actually, there's massive amounts they can do in order to help.

Speaker 1 You know,

Speaker 1 you you you talk about improving public services with ai but when you look at the i.t revolution and how much it's improved let's say market services versus how much it's improved public sector services there's clearly been a big difference should it would it if you go back to it would it have just been better to privatize the things that i.t could have enabled more of like education and what lessons does that have for ai where should we just you know the public sector didn't seem that good at integrating i.t maybe we'll be bad at integrating ai let's just privatize healthcare, education as much as possible, because all the productivity gains will come from the private sector or in those things, anyways.

Speaker 2 Yeah, no, it's a great question. And it's the single most difficult thing because

Speaker 2 you can't just hand everything over to the private sector because at the end, the public will expect the public interest to be taken account of by government.

Speaker 2

And, you know, you may say, well, government's useless at protecting the public interest. That's another matter.

But people will, people.

Speaker 2 No, people on the whole, people in America, people in the UK, they're not going to say, okay, just hand it over to these tech giants and let them run everything. However,

Speaker 2 I do think what should happen, and we have a whole program in my institute now, which we call the reimagined state, right?

Speaker 2 And I think if you look at, there was a minimalist state in the 18th century and in the first part of the 19th century that grew in the last...

Speaker 2 part of the 19th century and first part of the 20th century into a maximalist state, right? Where you look for government to do a lot of things for you and the state grows large.

Speaker 2 I think we should reimagine the state today as a result of this technology revolution and make it much more strategic.

Speaker 2 It's much more about setting a framework and then allowing much more diversity, competition.

Speaker 2 And the hardest thing about the public sector in those circumstances is to create self-perpetuating innovation. You know,

Speaker 2 if you don't innovate in the private sector, you go out of business, right? If you don't innovate in the public sector, I mean, you're still there, right? It's just the service has got worse.

Speaker 2 And so I think this is

Speaker 2 the really tough intellectual task.

Speaker 2 How do you, for example, in education today, I mean, how many kids in America are actually, you'll have a significant tailor of kids that are taught really badly, right?

Speaker 2 Okay, same probably in any Western country.

Speaker 2 No one today should be taught badly, right? Everyone should be taught, by the way, also on an individual basis, on a personalized basis.

Speaker 2 And if you look at, if you look, take what, because we work with them, what Sal Khan's doing, for example, with the Khan Academy, and there are other people doing great things in education using technology.

Speaker 2 We should be able to create a situation in which young people today are able to learn at the pace that is good for them. And no young person should be without opportunity.

Speaker 2 But how you reform the system to allow that to happen,

Speaker 2 that's the big challenge. But you know, in time, and like with the healthcare system, you know, you will end up with an AI doctor, you'll end up with an AI tutor.

Speaker 2 The question will be, what's the framework within which those things operate? And

Speaker 2 how do we use them to allow a better service and probably to allow a lot of the people within the healthcare or education systems to concentrate on the most important part of their learning rather than, for example, if you're a doctor having to write up a whole lot of notes notes after a consultation or do lesson planning if you're a teacher.

Speaker 2 Yeah.

Speaker 1 Going back to TBI for a second, when you give a leader some sensible advice and then they don't follow through on it, what usually is the reason that happens?

Speaker 1 Is this because it's not politically palatable in their country? Is it because they don't get it?

Speaker 1 Why is to the extent that you have good advice that's ignored? Why does that happen?

Speaker 2 It happens usually for two reasons.

Speaker 2 Number one, it's really hard to make make change. You know, what I learned about

Speaker 2 making change is that there's a certain rhythm to it. You know, when you first propose a reform, people tell you it's a terrible idea.

Speaker 2 When you're doing it, it's absolute hell.

Speaker 2

And after you've done it, you wish you'd done more of it. And, you know, that is so sometimes people just find the system too resistant.

There might be vested interests. that get in the way of it.

Speaker 2 I mean, I sometimes come across countries that are island states with warm weather, but they get all their electricity from heavy fuel oil, you know, when they've got limitless amounts of solar and wind that they could be using, but it's vested interests.

Speaker 2 The other thing is

Speaker 2 government, I sometimes say it's that government is a conspiracy of distraction because you've got events and crises and scandals.

Speaker 2 And the most difficult thing is to keep focused when you've got so many things that are diverting you from that core task. And what often happens with leaders,

Speaker 2 sometimes what we do with our leaders is we say to them, okay, we're going to do an analysis of,

Speaker 2 here are your priorities, here's how much time you spend on them. And you end up literally with people spending 4% of their time on their priorities.

Speaker 2 And you say, well, no wonder you're not succeeding.

Speaker 1 In my recent chat with Mark Zuckerberg, he mentioned how cybercrime is a huge concern with these new AI models, where criminals can use these models to increase the volume and complexity of their attacks.

Speaker 1 Current cybersecurity defenses are not prepared for this future. As new threats emerge, organizations lack the tools to effectively and quickly assess and augment their defensive posture.

Speaker 1 My sponsor today, Prelude Security, ensures that organizations can exceed the speed of new threats by automating critical functions of their security response.

Speaker 1 Using AI, Prelude rapidly transforms complex intelligence into actionable outcomes to find attackers, update defenses, and validate that you're protected against them.

Speaker 1 Once a new threat arises, Prelude is the first place your board members, security leaders, and psychops teams will look to know with certainty that their defenses will protect them against the latest threats.

Speaker 1 So if you're responsible for your organization's cyber defense, check out prelude security.com slash speed. All right, back to Tony Blair.

Speaker 1 So when you look back at your time as prime minister, or I'm not necessarily picking on your time, just any head of state and

Speaker 1 Western government or any government,

Speaker 1 how much of the time they spend is fundamentally wasted in the sense of the three priorities you would have identified for Singapore in the 1960s or something.

Speaker 1 It's not fundamentally moving the ball forward on things like that. You know, it's like meeting people, ambassadors,

Speaker 1 press, whatever. How much of the time is just that?

Speaker 2 A lot. I mean, I don't know.

Speaker 1 Greater than 80%, 90%?

Speaker 2 No, that would be too high, I think, but

Speaker 2 a lot and a lot more today, because people are expected.

Speaker 2 So I have this

Speaker 2 thing that I often say to

Speaker 2 the leaders, and I think this is the single biggest problem with Western politics today.

Speaker 2 You know, sometimes

Speaker 2 my kids were younger, and I used to speak with them, and I would say to them, you know,

Speaker 2 work hard, play hard, right? If you work hard, play hard equals possibility of success. Play hard, work hard is certainly failure, right?

Speaker 2 Because you'll play so hard, you never end up working hard, right? The equivalent in politics is

Speaker 2 policy first, politics second. In other words, work out what the right answer is and then work out how you shape the politics around that.

Speaker 2 But actually what happens to a lot of systems today is it's politics first and policy second. So people end up with a political position.

Speaker 2

They've chosen for political reasons. And then they try and shape a policy around that politics.

And it never works.

Speaker 2 Because the most important thing, and this is why I say to you about policymakers and intellectual business, is you've got to get the right answer. And there is a right answer, by the way.

Speaker 2 It's, and often, you know, the reason why it's so difficult to govern today is there's so much political noise, it's hard to get out of that zone of noise and sit in a room with some people who really know what they're talking about and go into the detail of what is the solution to a problem.

Speaker 2 And, you know, sometimes when I talk to leaders about this and

Speaker 2 I find that they just say to me, well, I...

Speaker 2 I don't have the time to do that. And I say,

Speaker 2 if you don't have the time to do that, you are going to fail. Because in the end, you won't have the right answer.

Speaker 2 and you've got to believe over time that the best policy is the best politics over time

Speaker 1 yeah how so structurally how would you change the it's not just the time you had to spend for example talking to the press but also the kinds of topics that draws attention to which are what statement your cabinet minister made on the bbc and some latest scandal

Speaker 1 Is that fundamentally like the 30 minutes of the PMQs is not the big deal. It's the two days you spend in anxiety and preparation that you were talking about in in the book.

Speaker 1 Is that fundamentally the attention distraction is the bigger issue than the actual time you spend on these events?

Speaker 2 Yeah,

Speaker 2 I think it is to a degree. I mean, I think the other thing is

Speaker 2 you undergo a lot of attack today in politics. And,

Speaker 2

you know, at a certain level, what happens, I mean, it could happen to celebrities. But they tend to have at least some sort of fan base that are constantly supporting them.

But

Speaker 2 with politics today, you can often be in a situation where

Speaker 2 you're almost dehumanized, right? You're subject to attacks on your integrity, your character,

Speaker 2 your intentions.

Speaker 2 It's possible if you're not

Speaker 2 careful that you're just sitting there thinking, this is really unfair. And you get distracted from focusing on the business.

Speaker 2 And that's why I will say to people, one part of being a political leader or any leader, I think, is

Speaker 2 to be able to have a certain sort of what I call a kind of a bit of a Zen-like attitude to all the criticism and the

Speaker 2 disputatiousness that will go on around you because it's just going to happen. And today with social media, it happens to an even greater degree.

Speaker 2 And, you know, one of the things I often say to leaders is you cannot pay attention to this stuff. I mean, okay, get someone to summarize it for you in half a page and you read it.

Speaker 1 Even the morning for you now.

Speaker 2 But honestly, you start going in, you go down that rabbit hole, you'll never re-emerge.

Speaker 1 Going back a little bit to your time in office,

Speaker 1 there was a unique unipolar moment that happens very rarely in history where the Anglosphere had much more power in the 90s and early 2000s than the rest of the world.

Speaker 1 Is there

Speaker 1 okay, so how, in what way did that feel different from today's world?

Speaker 1 And is there something you wish in the way the institutions were set up at the time and were carried forward now that you would maybe change, or

Speaker 1 I mean, we had there was like a key opportunity in the unipolar moment. How should that have been used? How well was it used?

Speaker 2 Yeah, it's difficult. I mean, we did

Speaker 2 try

Speaker 2

a lot, you know, contrary to what's sometimes written, for example, with Russia. And I, you know, I dealt with President Putin a lot when I was prime minister.

And,

Speaker 2 you know, we also took the, I think it was myself and President Clinton who took the crucial decision to bring China into the world's trading

Speaker 2 framework.

Speaker 2 And,

Speaker 2 you know, the G7 at the time was the G8 with Russia there and, you know, China would always be invited.

Speaker 2 I think we did try.

Speaker 2 I honestly think we tried a lot to recognize that we were going to live in a new world, the power was going to

Speaker 2 not shift from the West in the sense the West will become not powerful, but the East was going to become also powerful.

Speaker 2 And I think we kind of did understand that and

Speaker 2 work towards that. The problem is that, and particularly in these last few years,

Speaker 2 certainly China and Russia have come to a position that is, in terms of fundamental values and systems, seemingly hostile to

Speaker 2 Western democracy. And that's difficult.

Speaker 2 I think what we underestimated was probably how fast India would rise, because at the time it didn't, it seemed India was still going to be quite constrained.

Speaker 2 We live in a multipolar world today. And personally, I think that's a good thing.

Speaker 2 And I think it's, in any event, it's an inevitable thing.

Speaker 2 And, you know, I think it's really important always to give this message to

Speaker 2 China, for example, that

Speaker 2 China, as of right, is one of the big powers in the world and as of right should have a huge influence.

Speaker 2 And I don't believe in trying to constrain or contain China, but we do have to accept that the Chinese system, as it presently is, is run on different lines to our own and,

Speaker 2 you know, is overtly in some degree hostile, which is why it's important for us to retain military and technological superiority, even though I

Speaker 2 believe passionately that it's important that we leave space for cooperation and engagement with China.

Speaker 2 Now, how much could we have foreseen of all of this back in those days?

Speaker 2 I'm not sure, but I think the world

Speaker 2 You know, sometimes one of the problems of the West is that we always think, we always see it through our own lens.

Speaker 2 And we always think, well, we could have done something different to change the world.

Speaker 2

But actually, the rest of the world operates on its own principles as well. So sometimes the change happens not because we didn't do something, but because the rest of the world did.

Sure.

Speaker 1

Final question. You interact with all these leaders today across probably dozens, maybe hundreds of countries.

Which among them is best playing the deck they've been dealt?

Speaker 1 Who is the most impressive leader

Speaker 2 adjusting for you know it doesn't have to be a huge country or anything given the deck they've been dealt who's who's best you see drages one of the things you must never ever do in politics is say who's your favorite leader who's done well because you will you will make one friend and many many enemies um

Speaker 2 so i i'm just going to answer it in

Speaker 2 this way

Speaker 2 that

Speaker 2 if you look at the countries that have succeeded today, if you look, for example, as any country that was third world become first world, was second world become first world,

Speaker 2 there are certain things that stand out and are clear, right?

Speaker 2 Number one, they have stable macroeconomic policy.

Speaker 2 Number two, they allow business and enterprise to flourish.

Speaker 2 Number three, they have the rule of law. And number four, they educate their people well.

Speaker 2 And

Speaker 2 wherever you look around the world and you see those things in place, you will find success. And whenever you find their absence, you will find

Speaker 2 either the fact or the possibility of failure. The one thing, however,

Speaker 2 that

Speaker 2 any country leader should focus on today is the possibility of all of these rules being rewritten. by the importance of technology.

Speaker 2 And the single most important thing today, if I was back in the front line of politics, would be, as I say, to engage with this revolution, to understand it, to bring in the people into

Speaker 2 the discussions and the councils of government who also get it, and to take the key decisions that will allow us to access the opportunities and mitigate the risks.

Speaker 1

That's a wonderful place to close. Mr.

Valair, thank you so much for coming on the podcast.

Speaker 2 Thank you for having me.

Speaker 1 I hope you enjoyed this episode with Tony Blair. If you did, I appreciate you sharing it with people who you think might enjoy it.

Speaker 1 As always, Twitter or group chats, wherever else is extremely helpful. And I'm doing ads on the podcast now.

Speaker 1

So, if you're interested in advertising, please reach the form and link in the description below. Other than that, I guess I'll see you next time.

Cheers.