Meet Taro, the Poke Bowl's Missing Secret Ingredient

Learn more about your ad choices. Visit podcastchoices.com/adchoices

Press play and read along

Transcript

Speaker 2 What I'll do is I'll just do our oli komo, and then that's just a chant that we do that welcomes people who've never been on the property.

Speaker 2 Ta ahe mai kama kani kili o o pu he o pu veo veo o kapoho la e la i la e o mauna ihike ake ke ala ili ili, o ke alakai ho nua

Speaker 2 e alaka imai, e kia i mai, e po mai ka imai e

Speaker 2 komo mai ka la io ne ya aina, he

Speaker 3 This is Scott Fisher. He works for the Hawaii Land Trust, and he was welcoming us to an ancient archaeological site on Maui where some of his ancestors once farmed taro.

Speaker 4 For those of you who, like us, are not fluent in Hawaiian, Scott helpfully provided a translation.

Speaker 2 So basically, it's talking about the wind that starts off with the wind that blows here.

Speaker 2 Pa'ahiahi Mai Kama Kanikili o'opu is the wind that carries the scent of the o'opu, which is a also refers to the fish pond because the fish pond was a freshwater fish pond and it grew tarot and particularly the freshwater fish species, the o'opu.

Speaker 3 We visited this site because once upon a time it helped support an entire empire in Hawaii, and while the fish were critical, what was really amazing was the tarot that was growing there.

Speaker 3 It might be gray and wintry in a lot of the northern hemisphere, but this episode, we at Gastropod are going on a tropical adventure.

Speaker 3 That's right, you're listening to Gastropod, the podcast that looks at food through the lens of science and history. I'm Cynthia Graeber.

Speaker 4 And I'm Nicola Twilley, and this episode is not just Sun, Sea, and Sand.

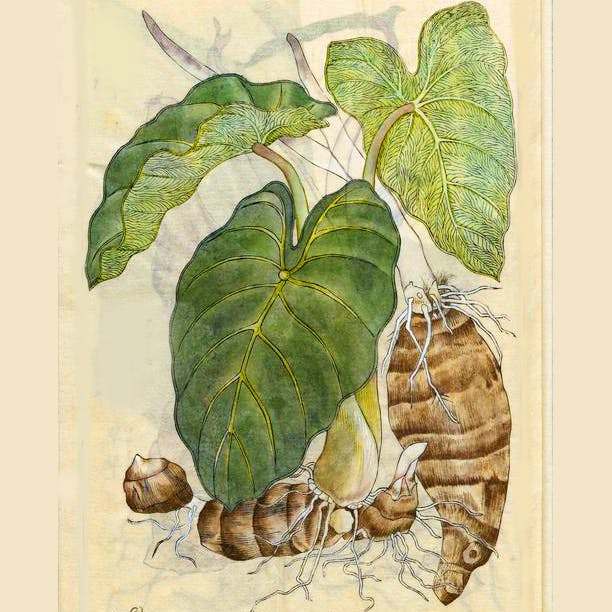

Speaker 4 We're also meeting a root veggie that a lot of North Americans have never tried, but that experts think is among the most ancient crops cultivated by humans.

Speaker 4 And it's one that some 500 million people still depend on today.

Speaker 3 Before we went to Hawaii, my only relationship with taro was in the form of taro chips purchased at Whole Foods. Sure, they're delicious, but it's kind of hard to imagine taro as a staple food.

Speaker 4

But that's exactly what taro was in Hawaii. The entire island chain built their cuisine around taro.

They considered themselves physically related to the taro plant. Taro was life.

Speaker 3 Although it's not originally from Hawaii.

Speaker 3 This episode, we have the story of an easily overlooked root that is actually kind of a lot of work and is also a little poisonous, but it once supported an entire civilization in the middle of the Pacific.

Speaker 4 But doesn't anymore. So why did tarot nearly die out on the islands where it was so essential and beloved, And what needs to happen to bring it back today?

Speaker 3 Gastropod is part of the Vox Media Podcast Network in partnership with Eater.

Speaker 4

Support for this show comes from Pure Leaf Iced Tea. When you find yourself in the afternoon slump, you need the right thing to make you bounce back.

You need Pure Leaf Iced Tea.

Speaker 4 It's real brewed tea made in a variety of bold flavors with just the right amount of naturally occurring caffeine.

Speaker 4 You're left feeling refreshed and revitalized, so you can be ready to take on what's next. The next time you need to hit the reset button, grab a Pure Leaf iced tea.

Speaker 5 Time for a tea break?

Speaker 4 Time for a Pure Leaf.

Speaker 2 You're at the Waihei Coastal Dunes and Wetlands Refuge. We're on the island of Maui.

Speaker 4 Picture lush green mountains in the distance, huge sand dunes like 15 stories tall, and the gorgeous blue Pacific in front of you.

Speaker 3 The site where we were standing was beautiful, but it also is one of the oldest known inhabited sites on Hawaii. It's one of the earliest places on Maui where Polynesian settlers first set up a home.

Speaker 2 People have been on the Waihe'i refuge for over a thousand years. The first evidence we have of people living on this property is actually about 15 or 20 feet away from where we're standing.

Speaker 4

One thing to know about Hawaii is it is one of the most isolated places on earth. Maybe the most isolated.

It's two and a half thousand miles away from the next decent-sized chunk of solid land.

Speaker 3 It is smack dab in the middle of the Pacific, and there were no people living on Hawaii until about 1500 years ago.

Speaker 3 That's when Polynesians traveled in massive canoes all the way across the ocean, again 2,500 miles in their canoes, and then out of the wide ocean expanse, they suddenly found the Hawaiian Islands.

Speaker 4 Paradise, right? But actually, weirdly, Hawaii wasn't very hospitable. The islands are volcanoes, and they've only emerged from the ocean pretty recently, at least in geological and evolutionary time.

Speaker 4

And because of that, there were were basically no edible plants there. They just hadn't evolved.

There's a great book called Foods of Paradise by Rachel Laudan. She's been on the show before.

Speaker 4 And she says that after that long canoe trip, those hungry Polynesians would have found a couple of ferns and some birds.

Speaker 3 There were plenty of fish to eat, of course, and seaweed, which is tasty and basically a vegetable, but that wouldn't have been enough to live on.

Speaker 3 There weren't any indigenous carbohydrates that grew on Hawaii, and we humans typically need carbohydrates.

Speaker 3 But luckily, the Polynesians had packed not only snacks for the long trip, but they also brought seeds and seedlings for the journey that they planned to plant and farm once they landed somewhere.

Speaker 4 One of those seeds was the coconut. We told you that story last fall.

Speaker 4 They also brought sweet potato and bananas, which were super popular back home, and breadfruit, also a traditional Polynesian staple, as well as the subject of a future episode of Gastropod.

Speaker 4 Stay tuned for that.

Speaker 3 They brought around 30 different plants with them, things like ginger and sugar cane, too, and they brought pigs and chickens, and of course, they brought taro.

Speaker 1 If you talk to anybody in the culture, if you mention kalo, kalo is revered. It's not like another crop, right? It's not like oala, sweet potato, it's not like ava, but ulu, kalo, and oala.

Speaker 1 That's the three main canoe plants, right?

Speaker 1 Kalo being the most important one.

Speaker 4 This is Babi Pahia.

Speaker 1 I'm a mahirai oki kalo, so I'm a farmer of the taro, the kalo.

Speaker 4 Kalo is Hawaiian for taro, and taro is also Hawaiian for survival. Back in Tahiti and the Marquesas and other Polynesian islands, taro was part of the rotation, but not central.

Speaker 4 But in Hawaii, the climate, everything was just right for taro, and the island's growing population absolutely depended on it. It was like the wheat or corn or rice of the Hawaiian islands.

Speaker 3 Some sources say that native Hawaiians pre-Anglo-colonization might have eaten as much as about 15 pounds of taro a day. That's kind of hard to even imagine.

Speaker 3

It'd be nearly all the food you'd be eating. And so it's really because of tarot that the Hawaiian Islands could be self-sufficient.

The reason people could keep living there.

Speaker 2 For those of us who are kanakamauli, for those who are Hawaiian, it is our story and we need to tell that.

Speaker 2 One of the most important things to get across is how we survived on these islands for a thousand years completely independent.

Speaker 2 You know, we did not rely on Costco and Target and all the things that we do right now.

Speaker 2 And the strength strength of our community is based on our ability to know how to live on these lands sustainably.

Speaker 3 These first Hawaiians couldn't have survived and grown and created a thriving society of more than a million people without tarot.

Speaker 3 And so taro became literally, at least in the Hawaiian creation story, it's literally a part of the family.

Speaker 1 If you go back in mythology about the culture, I mean,

Speaker 1 Haloa was the first stillborn son of Wakea and Papahunua.

Speaker 1 And they planted their son in the corner of on the outside of the house and lo and behold up sprang the first tarot plant.

Speaker 4 But then the couple who by the way are also known as sky father and earth mother they tried for another baby and they were rewarded with a little baby human the first Hawaiian.

Speaker 3 The point is that the first Hawaiian human was the little brother of the first tarot. So tarot is like everyone's great great great great uncle.

Speaker 1 So if you look at the genealogy of course like in the Hawaiian culture, they're very hep on the genealogy. So when you look at the genealogy, it goes all the way back to that first Hawaiian man.

Speaker 4 So back at the sand dunes on Maui, those early Hawaiians, maybe not the very first, but some of the earliest ones, they got their brother taro and they did something different than their Polynesian ancestors.

Speaker 4 They started growing it in a pond.

Speaker 2 So we're looking at the seven acre fish pond. So of all the people of Oceania, only the Hawaiians developed fish ponds.

Speaker 3 The fish fish pond we were looking at is dry now. It just kind of looked like an empty, shallow pool, but a pool that's the size of about three entire city blocks.

Speaker 3

We walked over to look at walls that used to hold in the water. They were built out of black volcanic rock.

There was no cement or anything. Everything was just carefully wedged together.

Speaker 2 You are standing on a ku'aona, or the wall of a tarot patch.

Speaker 1 Right here.

Speaker 2 So you can see the lines just like this.

Speaker 4

A tarot patch in a fish pond basically looks like a rice paddy. It's a little flooded field.

And building one required quite a bit of engineering.

Speaker 4 You had to build the walls of the pond and then you had to fill the pond.

Speaker 2 And so the way that this particular system operated was it was built near the coast, so you had to have some connection to the ocean, but it was fed from a river that was not too far away.

Speaker 3 The river might have been close by, but it wasn't here on this site. Hawaiians had to build an aqueduct to divert the water flowing down from the mountains over huge dunes and bring it into the pond.

Speaker 3 Scott pointed out where we could see traces of that too.

Speaker 2

This is the aoai here. You can see it's rockwai.

Yeah, so it would have been coming around.

Speaker 2 We had an engineer look at it and you can kind of see from this distance, you know, kind of seeing where the where the water would have been. Five to seven million gallons a day is what he estimated.

Speaker 2 So pretty amazing system.

Speaker 4 The whole system put together was super clever.

Speaker 4 There was a sluice gate to let little fish in from the ocean, but it was designed so big fish couldn't get out and then the fish would poo in the water, which was free fertilizer for the tarot.

Speaker 3 In general, tarot needs fresh water to grow, but some varieties were able to grow in a mixture of fresh and salty, basically brackish water, in the parts of the pond that were the furthest away from the ocean.

Speaker 2 What it seems like as we're piecing the puzzle together, the tarot seemed to have been cultivated in the back end, and then the front end would have been better habitat for the fish.

Speaker 4 And the whole combination together produced a lot of food. Scott estimates that this one pond could produce a ton of fish a year and even more tarot.

Speaker 2

You know, let's just say 12,000 pounds of collo being produced annually per acre. That's a lot.

For seven acres, that's

Speaker 2 92,000 pounds of collo annually.

Speaker 3 This fish pond fed people on Maui for hundreds of years, right up until the turn of the last century.

Speaker 2 From what we can tell, by about 1906, it was abandoned. It was abandoned because

Speaker 2 it was going to be turned into a dairy. But definitely by 1919, they dredged out the wetlands entirely and they stopped the flow of the awai or the aqueduct.

Speaker 2 and so that really put an end to the fish pond.

Speaker 4 Scott and his colleagues started working on restoring this fish pond in 2003. It's taking a long time partly because no one really farms this way anymore so no one knows exactly how to do it.

Speaker 4 As we walked around we came to a set of two narrow walls together like a corridor.

Speaker 2 The feature we're standing on right now seems to be a system designed to regulate flow and we're not exactly sure how it operated. This is why we're you know we're still very much novices.

Speaker 2 So what we're looking at is basically two walls parallel to one another and with a trough in between.

Speaker 2 And we're not exactly sure how it functioned until we make that connection to the ocean.

Speaker 1 We won't know. You know,

Speaker 2 we're all novices because this knowledge has really been lost.

Speaker 4 This fish pond system was Hawaii's unique contribution to growing taro, but it wasn't the only way taro was and still is grown on the island.

Speaker 1 What about the dryland taro's? Well those were grown along the cloud line on the mountains, right? Because that's where the moisture moisture was.

Speaker 3 Once upon a time, there were hundreds of varieties of taro growing in both the fish ponds and on the mountains. Scott estimates there were maybe 600 different kinds of taro.

Speaker 3 All of these different root veggies were different sizes. They matured at different rates.

Speaker 3 Some were starchier, some were sweeter, some were used for medicine, some were reserved for the nobility, some were the varieties everyone could eat.

Speaker 4 It's like apples for us.

Speaker 4 We made an episode all about apples, and there are hundreds and hundreds of varieties: ones that grow better in different places, ones that are better for eating raw or cooking, ones that store well.

Speaker 4 Tarot was the same. Emphasis on was.

Speaker 1 Today, if you can find 60, you're lucky.

Speaker 3 That's if you really know where to look, like even in university collections. But if you were to just ask most Hawaiians, they only really know one kind of tarot.

Speaker 1

People think we only have purple tarot. No, we got all kinds of.

We got yellow tarot, orange tarot, blue tarot, green tarot, white tarot.

Speaker 4

We got all kinds of tarots. Bobby knows all the tarots all over the world.

Taro isn't native to Hawaii, like we said.

Speaker 4 Researchers think it originally came from India or Southeast Asia, but these days it's grown all over. Nigeria, China, Vietnam, they're all major taro producers.

Speaker 1 When I was working at the University of Hawaii doing research work with tarot production, one of our jobs was to go around the world and collect all these different varieties of taro.

Speaker 3 It might not surprise you, listeners, to hear that Bobby's favorite is the homegrown variety.

Speaker 1 In my opinion, the Hawaiian tarots is superior

Speaker 1

to all the other tarots around the world. You know why? Because I had to eat them all.

I ate over 2,000 varieties of taro.

Speaker 1

And not because I'm Hawaii and I'm from here, it's just the quality. They took it to another level, really.

My cupunas, they really did. Especially the flavor.

Very full-bodied, nutty.

Speaker 4 Like he said, Bobby farms his superior Hawaiian taro in a dry field, not in a pond. And he brought us to his farm to see what all the fuss is about.

Speaker 3 We've been talking about how tarot is really the taste of Hawaii, but we hadn't seen it or tasted it yet. That's coming up after the break.

Speaker 4

With the Spark Cash Plus card from Capital One, you can earn a limited 2% cash back on every purchase. And you get big purchasing power.

So your business can spend more and earn more.

Speaker 4 Stephen Brandon and Bruno, the business owners of SandCloud, reinvested their 2% cash back to help build their retail presence. Now, that's serious business.

Speaker 4 What could the Spark Cash Plus card from Capital One do for your business?

Speaker 1 Capital One, what's in your wallet?

Speaker 4 Find out more at capital1.com slash spark cash plus. Terms apply.

Speaker 6 So you can see here we have one, two, three, four, five, six, seven rows.

Speaker 6 The varieties, that looks like a Manaulu here.

Speaker 6 And then we have turmeric in the middle. And then we have two more lines of taro, and that looks like Maui Lehua.

Speaker 4 This is a young taro farmer. He's called Jake Ooga, and he's part of a collective that grows tarot on some land that Bobby manages because Bobby doesn't just grow his own taro.

Speaker 1 I'm a farmer of farmers, so I help people grow.

Speaker 3 Jake is one of three people farming this particular taro patch. He and his partner Whitney Cunningham came to Maui a couple years ago and they met Winsom Williams.

Speaker 3 She'd already started farming these seven acres with Bobby's support.

Speaker 5 Here on our farm, we grow about 12 different varieties, and the colors can range from purple to white. We have one that has like a green hue in it and then a mana ulu is like a yellow.

Speaker 5 There's also like red hue taros as well. So there's a whole like beautiful spectrum that you can play around with.

Speaker 4

The taro look kind of like most root vegetables. Big green leaves on chunky stalks.

Some of the stalks are colored too like Swiss chard.

Speaker 4 The ones that were big enough to harvest, we could see the shoulders of the big knobbly corm, the taro root itself, kind of poking out of the the soil.

Speaker 5

This is a really nice variety. This is the mana lauloa variety.

You can tell from the really dark color of the stalk.

Speaker 5 And this one is interesting because, like, the longer it stays in the ground, the more starchy it gets.

Speaker 3 Bobby says the corm, the root, it gets all the attention, but the whole plant is edible.

Speaker 1

I eat the leaf, the stem, and the corm. You can use it in different ways.

Use it, cook it like a spinach.

Speaker 4 That said, you do have to be careful. Whitney told us taro is not at all palatable straight out of the ground.

Speaker 8 So there's a ton of access deer here.

Speaker 5 They won't eat that because of this.

Speaker 3 It knows it gives them scratchy throat.

Speaker 8 So that's kind of a nice deterrent that we don't have to worry about.

Speaker 7

And the same thing with the wild boars. They won't eat tarot.

They literally will come and eat cassava right next to it and will not touch the tarot at all.

Speaker 3 And that's because taro has a chemical in it called calcium oxalate that can be really painful if you eat the plant raw. It hurts deer, it hurts pigs, and it hurts our throats too.

Speaker 3 Bobby told us never ever to eat any part of the tarot plant raw. He said we would really regret it.

Speaker 1 Oh, you're going to be one sorry, Kempo.

Speaker 1 You don't want to eat that because your throat is going to, oh, you're going to get all itchy, and some people get hives.

Speaker 1 It's bad, bad news.

Speaker 1 Ever, ever do that.

Speaker 7 It's like akin to swallowing glasses, how people describe it.

Speaker 1 Yeah.

Speaker 1 I think I'm going to push.

Speaker 1 I wouldn't recommend. I wouldn't recommend.

Speaker 4 It's not just eating it. Apparently, even handling the plant can give you hives.

Speaker 5 If you clean a bunch of it, and I mean, we'll do 500 to 1,000 pounds like in a harvest sometimes, it will make your hands and your legs a little bit scratchy from working with it too much.

Speaker 3 So, if you do want to eat the greens, first you have to take the stem out and then you have to cook the greens for a long time. And if you want to eat the root, prepare to wait for hours.

Speaker 1 So, you harvest it, and then they'll either boil it or steam it. Usually, they'll cook it in an earthen oven, a emu.

Speaker 4 Whichever method you pick, just don't start out completely ravenous because this is not a 15-minute meal. Whitney told us she steams taro for four hours before the next step in the process.

Speaker 4 Today, there are shortcuts. Scott says he just throws it in the pressure cooker for 40 minutes, which is a lot more manageable.

Speaker 3 Once it's steamed and no longer going to cause you to feel like you have broken glass in your throat, then you can start to do all sorts of things with it.

Speaker 3 You can eat steamed taro as is, but probably the most traditional thing to do is to pound it with a volcanic stone.

Speaker 3 The stone is like a cone shape, and there's a handle to grip it at the narrow end, so you have a big wide surface to smush all the steam tarot with.

Speaker 5 This is the stone right here. So this is called the pohaku

Speaker 5 and it's a river stone.

Speaker 5

Very difficult to make. I've tried to make a couple and I always end up breaking them.

But yeah so this the weight of this we I'll show you the board as well. Let me grab it real quick.

Speaker 4 Winsom grabbed a tarot board for us. It was about the size of a small child and shaped kind of like a long flat dish like a skateboard with a rim.

Speaker 4

She told us you have to wet it a little before you get started. And the other thing you have to do is grab a bunch of friends.

Tarot pounding is a group activity.

Speaker 5 And then we might steam up like, say, 50 pounds of tarot.

Speaker 5 Everyone arrives, cleans the tarot together, and then you put the steamed tarot on the board, and then you have your stone, and you're literally...

Speaker 3 Winsom pretended to push the tarot down with the stone and then pull the stone towards her. Like she was almost breaking down and mashing up the tarot in long, narrow circles over the board.

Speaker 3 She said if she had real cooked taro on the board, she'd be getting out lumps and flattening and mashing it all against the board.

Speaker 5 You're literally hitting the taro with a stone, kooi, like cutting the taro with a stone, and the act of hitting it switches the molecular structure and helps with that fermentation process because taro is a fermentable starch.

Speaker 5 And so then the consistency sort of changes from this like starchy potato texture to more of like a dough. It's really malleable dough.

Speaker 4 These days there are machines that compound taro, taro, but for purists, it's not the same.

Speaker 1 The texture is different versus kui, what we call kui with the stone.

Speaker 1 It stays more heavy, the pounded one with the stone. It's a heavier texture, not as fine.

Speaker 3 Either way, you add some water to the mash and you start to make poi. That is probably the most traditional of all Hawaiian foods made of taro.

Speaker 3 It's basically thinned-out taro dough that turns into a lightly sour, saucy, kind of porridge-like dish.

Speaker 5 So, um, with the poi, you would just leave it out. Oftentimes, it would be in like a calabash in a big bowl, and so that fermentation process would like slowly start to happen as it's set out.

Speaker 4 This is just like making sauerkraut.

Speaker 4 The bacteria and yeasts that are naturally on the surface of the taro root get to work and start feeding on the starches and excreting acids, and the poi gets more and more sour as the days go on.

Speaker 5 So, if you go to like some of the grocery stores here, they have a bunch of like a shelf with all these pois on it, and it'll have a different color twist tie.

Speaker 5 So, you'll have like one that will be from like Monday, Wednesday, and Friday are the delivery days.

Speaker 5 And so, people who like it more sour will go towards like that color of twist tie versus like the closer.

Speaker 3 The reason poi is a big deal is that, weirdly, unlike a lot of other root vegetables, you can't store taro for long, it'll go bad in a couple of days.

Speaker 3 So, originally, fermenting taro into poi was a useful technique for preserving it.

Speaker 4 Like we said, you can eat taro just steamed, you can do a bunch of different things with it, but poi was and is the main way to eat taro in Hawaii.

Speaker 1 When I was growing up, there's poi, a bowl of big, big bowl of poi on everybody's table, no matter where you went.

Speaker 3 Noah Kekueva-Lincoln agrees with Bobby. He's a researcher at the University of Hawaii.

Speaker 3 He focuses on indigenous crops and farming techniques, and he says he can't even remember the first time he ate taro or kalo.

Speaker 9 Kalo is, in particular, favored as an infant food.

Speaker 9 From a food science perspective, kalo, I believe, has the smallest starch grain size of any staple crop, crop, which makes it extremely easily digestible.

Speaker 9 And so it wasn't the only food I ate as a child, but you know, as an infant, as a baby, poi was one of, if not my first food.

Speaker 4 At this point, it was clearly long past time for Cynthia and me to try some tarot, specifically some poi, so we went to find some.

Speaker 10 I'm Chef Sheldon Simeon. We are sitting at my new restaurant, Tiffany's, in Wailuku, Maui.

Speaker 3

You might have caught Sheldon on on Top Chef. He was a finalist in season 10, and he also wrote a book called Cook Real Hawaii.

And we were lucky enough to have him cook for us.

Speaker 10 Here we have our offerings of taro or kalo, your traditional fish and poi, poi that's been steamed and then pounded to a paste with some fresh aopoke or Pacific blue marlin that was just caught yesterday.

Speaker 10 This is gonna be almost as

Speaker 10 if how the early settlers, the early Hawaiians had it.

Speaker 10

Here we have limu lipoa, which is seaweed that is very known to Maui. It has this, you know, flavor of the ocean and the sea.

And the fish is just dressed with salt.

Speaker 10 There's no soy sauce or sesame or mayonnaise. It's not like how you see poke

Speaker 10 nowadays,

Speaker 10 but just beautiful freshness.

Speaker 10 And then that saltiness is going to pair great with their spoi, which is a few days old, so it has a touch of sourness, but I think it lends itself well to the fresh fish.

Speaker 4

The poi was a super thick, smooth, purple paste, kind of like a scoop of purple pureed potato. Sheldon told us we could put some on the fish cubes, or we could kind of alternate.

Both were legit.

Speaker 3 I'm gonna taste the tarot first, just to see what it tastes like.

Speaker 3 There's a little bit of that sourness to it. You can taste the fermentation starting.

Speaker 10 Exactly, starting to go on there.

Speaker 3 Okay, now try them together.

Speaker 4 I did not think the poi would be great with the fish and it is. It really works.

Speaker 10 Yeah, I mean these Hawaiians knew what they were doing.

Speaker 3 There's a real like purity of flavor. Like the fish is so fresh and beautiful and the taro is so kind of earthy and a little tangy and there's just this kind of very clear flavor profile.

Speaker 3 You know, you kind of know exactly what it is that you're eating.

Speaker 10 This is like my favorite form of what I crave when I get back with poke that is like super fresh and very of the sea.

Speaker 10 And, you know, this, you can't get closer to earth than poi.

Speaker 10 So that beautiful synergy of them both, which the Hawaiians understood better than anybody in this world, I believe, you know, that's match made in heaven right here.

Speaker 3 Sheldon also prepared another super traditional Hawaiian taro dish for us.

Speaker 10 Then we have kulolo, which is a steamed taro dessert with coconut milk and brown sugar. But,

Speaker 10 you know, it still has that texture of the poi, of the taro.

Speaker 4 This looks like fudge. It does.

Speaker 10 Yeah, basically.

Speaker 4 Like a cross between mochi and fudge. Yep.

Speaker 3 I would eat this every day.

Speaker 4

It's delicious. It's not too sweet either.

It's not like your teeth hurt like fudge. This is really

Speaker 10 three ingredients: taro, coconut milk and uh and sugar kulolo traditionally was made in the imu so underground in that uh in the oven now this one was just just made in a regular oven but when it's cooked on the ground you get the impart of the smokiness

Speaker 4 it's that's like that's heaven to me right there sheldon's dishes of poi and cololo couldn't have been more delicious or more traditional but today they're not the only way to enjoy tarot.

Speaker 4 And they're also not so common anymore.

Speaker 3 Because while tarot was once the crop that basically sustained Hawaiians sustainably for hundreds of years, today it's barely grown there at all. What happened to Hawaii's sacred crop after the break?

Speaker 4

Thumbtack presents. Uncertainty strikes.

I was surrounded. The aisle and the options were closing in.

There were paint rollers, satin and matte finish, angle brushes, and natural bristles.

Speaker 4 There were too many choices. What if I never got my living room painted? What if I couldn't figure figure out what type of paint to use? What if

Speaker 4

I just used thumbtack? I can hire a top-rated pro in the Bay Area that knows everything about interior paint, easily compare prices, and read reviews. Thumbtack knows homes.

Download the app today.

Speaker 1 This is our mapo taro.

Speaker 10 So like mapo tofu, but uh with taro.

Speaker 4 Traditional taro is pretty good, but for Sheldon, dishes like poi and kololo, they're just the tip of the taro iceberg.

Speaker 4 He likes to use taro in all kinds of different dishes, like his version of mapo tofu, which is a dish you can find at Chinese restaurants. It usually has minced pork and tofu and a spicy sauce.

Speaker 10 We've got some crispy taro that we boiled and then diced up and then fried and dehydrated and then tossed with sashon peppercorns for some texture. Over the top of it.

Speaker 3 Sheldon mixed taro into the dish in a number of ways. On top of that crispy taro, he also diced up some steamed and then roasted taro.

Speaker 3 He turned the thickened taro he used for the fudgy traditional dessert we had just tried into kind of savory taro dumplings, and he mixed in poi to thicken the sauce.

Speaker 10 So you've got savory, sweet, crunchy,

Speaker 10 chewy.

Speaker 10 I love all, I love food with texture, right?

Speaker 1 Oh, it smells incredible, right? So excited.

Speaker 3 I can't even tell you how excited I am for this dish.

Speaker 1 I love it. Okay.

Speaker 4 All right, here we go. Yum.

Speaker 1 I mean,

Speaker 4 this is incredible. I would eat this by the bucket.

Speaker 1 Wow. Wow.

Speaker 10

I loved what the poi did to it. Again, the sourness of this poi kind of uplifted the spices in it too.

It gave that mouth feel to the whole

Speaker 10 dish. So,

Speaker 10 you know, I'm still discovering new ways to use

Speaker 10 our traditional ingredients and applying it into this like modern taste of it. Poi might not be for everyone, but if I can get you to taste taro through Mapotofu, so be it.

Speaker 4 Sheldon did not grow up eating a lot of super traditional Hawaiian food, but he did eat taro.

Speaker 10 I mean, I'm Filipino, so a Filipino household, a lot of Filipino food,

Speaker 10 but yeah, Poi was always there.

Speaker 3 The Filipino community in Hawaii is one of the largest ethnic groups in the state. Most of them moved there in the 1900s to work on the sugar plantations.

Speaker 4 What happened was that in 1876, the independent Kingdom of Hawaii signed a big treaty with the U.S., a treaty that really opened the door to Hawaiian exports to the U.S.

Speaker 4 And that changed everything on the islands.

Speaker 3 This is what spurred the creation of huge plantations in Hawaii.

Speaker 3 First, it was plantations growing sugar, and then came the pineapple plantations, and lots of immigrants, mostly from Asia, moved to Hawaii to work on these plantations.

Speaker 10 Different cultures that influence Hawaii cuisine: Filipino, Japanese, the Chinese workers Puerto Rican

Speaker 10 What else did I say miss Portuguese do they say Portuguese already

Speaker 10 but uh yeah all of these different cultures that's what's amazing about Hawaii now you have all these influence from all these different cultures that I felt so familiar with you know growing up I'm Filipino but Cooking with Hawaiian ingredients, Chinese flavors, Japanese

Speaker 10 techniques,

Speaker 10 it feels very Hawaii to me.

Speaker 4 This mass immigration to work in plantations resulted in a delicious culinary fusion, but it wasn't the first big shift in Hawaiian demographics.

Speaker 4 Noah told us the big shift happened when Europeans first showed up.

Speaker 9 Like a lot of places, you know, the most devastating impacts were introduced diseases.

Speaker 9 And so, you know, at the time of contact in 1778, the population is estimated to be between about 400 and 800,000 people.

Speaker 9 And that number had dwindled to 40,000 only 100 years later.

Speaker 4 I mean, that's hard to even imagine. Nine out of every ten Hawaiians died.

Speaker 9 So, you know, that really devastated everything about the society.

Speaker 9 The land management systems, the socio-political systems, you know, all of that really lost, you know, most of its power with that decline in population.

Speaker 3 And you won't be surprised to hear that there were foreign business people perfectly ready to move into that vacuum.

Speaker 9 And Hawaii very rapidly transitioned into a kind of plantation-based economy. Most of the state, most of the big Hawaiian ag systems became the major plantation crops of sugar and pineapple.

Speaker 4 These big plantations obviously took a lot of land, land that had previously been used for growing stable crops like taro. And the plantations took another important resource, too.

Speaker 1 When sugar cane, the sugar cane industry came here, right? So they had to make water courses to bring water to the arid sides.

Speaker 1 However, of course, they didn't check with the natives from that area, right? They just took it.

Speaker 9 And I mean, just to give you a scope of the problem, you know, on the East Maui irrigation ditch, there are 27 river valleys in a row that were 100% dewatered.

Speaker 3 No water means you can't farm taro. And then all the immigrants to Hawaii, they wanted to eat their own staples, and so the taro ponds that were left became rice patties.

Speaker 3 Growing taro today in Hawaii isn't common. Some of the taro dishes like Poi are made from imported taro.

Speaker 4 Taro has almost disappeared in Hawaii, but there's still plenty of it grown elsewhere. The leaves and roots are a staple in many parts of West Africa and eastern India.

Speaker 4 Taro is big in China, and it's still popular in lots of Pacific islands like Papua New Guinea.

Speaker 3

We mentioned our previous tastes of taro had been through chips we bought at the supermarket. One brand I've seen at Whole Foods is grown in Honduras.

People are even growing it in the U.S.

Speaker 3 There are farmers trying it out in North Carolina because the changing climate might make it a great crop to grow there.

Speaker 4 But back in Hawaii, even imported taro isn't that common. Today, there just isn't much taro being eaten in Hawaii.

Speaker 4 Remember that before Europeans arrived, historians think that Hawaiians ate as much as 15 pounds of taro a day? By the 1980s, that average was five pounds a year.

Speaker 1 Oh, like 90%

Speaker 1

do not eat it. Do not eat taro.

It's hard to find.

Speaker 1

You can't even find it. You don't see it in the stores.

So it's hard to find and it's expensive.

Speaker 3 A pound of rice costs less than a dollar, but taro might cost about seven to ten dollars for the same pound of food.

Speaker 3 Taro is only grown and harvested by hand on a relatively small scale in Hawaii, which is expensive. There's pretty much no huge industrial taro farms on Hawaii, and it doesn't store well.

Speaker 3 So it just can't compete these days.

Speaker 4 Losing tarot as an accessible, everyday staple is not just kind of a nostalgia thing. NOAA says it's been a disaster for Hawaiians.

Speaker 9 I mean, most visible perhaps is, you know, the fact that native Hawaiians have the highest rate of obesity, the highest rate of diabetes, you know, of any ethnic group in Hawaii.

Speaker 9 And there have been a number of studies that show a return to our traditional staples has a huge impact on reducing those health issues.

Speaker 3

But it's not just the physical impacts. Colonization destroyed Hawaiian culture in a number of ways.

They were banned from speaking their native language and schools.

Speaker 3 Their culture was considered a tourist attraction. And remember that taro, Kalo, in the Hawaiian origin story, it was the buried stillborn brother of the first Hawaiian man.

Speaker 1 Kalo

Speaker 9 was literally, in our genealogy, our elder brother

Speaker 9 and to me a relationship with Kaolo as a food and as a

Speaker 9 symbol as an icon of our natural environment to be divorced from that really shattered Hawaiian people's identity. It is

Speaker 9 hard to be Hawaiian

Speaker 9 without your elder brother, without having a relationship with

Speaker 9 Kahlo and with the environment.

Speaker 9 And that was such a core part of Hawaiian identity that I think when that was removed, it had tremendous personal and social impact on our people that is something that hasn't been quantified the way that diabetes and obesity has, but I would say is arguably probably much more impactful.

Speaker 4 In the past few decades, more and more people have realized that the future of Hawaiian food and farming needs to include traditional crops.

Speaker 1 And that's the mission of why I grow taro, is to put food back on people's tables so they can afford to eat it.

Speaker 1 I mean, hello, we can't even afford to eat our native food, something's wrong with that.

Speaker 3 Bobby thinks farming tarot shouldn't just be for farmers in Hawaii. It should be for everyone.

Speaker 1 You should definitely grow taro.

Speaker 1 That's automatic. You're a citizen over here.

Speaker 3 You should grow taro. None of this matters, though, if you can't access land.

Speaker 3 Bobby's worked with a rich developer to get access to 300 acres that's a conservation easement, meaning it can only be used for farming, and he's managing it and training other farmers who are also farming the land with him, like Whitney, Jake, and Winsom.

Speaker 4 You need land to grow tarot, but you also need water. And like we said, that was also taken away by the plantations.

Speaker 4 And when the plantations closed up shop towards the end of last century, their wealthy owners didn't let go of their water rights willingly. They pivoted to tourism, which meant development.

Speaker 1

You cannot develop real estate without water. So they're banking.

They're water banking. They don't want to give it back.

Speaker 9 And because, you know, 150 years of infrastructure and industry were built upon those water sources, it becomes very, very hard to reverse it.

Speaker 3 Getting that water back, returning it to Native Hawaiians, allowing them to use it for things like farming, that's been the focus of activism and even court cases recently.

Speaker 9 In the last five years or so, there's actually been a couple of really important

Speaker 9 rulings in which water has been returned to traditional farmers, to the native rivers.

Speaker 4 Scott told us that he and his colleagues had to fight long and hard to get the water back to rebuild the ancient tarot pond, but eventually they were successful. We have a legal right to it.

Speaker 2

We have a legal claim to the water now, which is a huge step. It took us 10 years to get that.

Now we need the process of actually bringing the water back in.

Speaker 2 And when we do, it will be a rebuilt fish pond that will be functioning. That's our goal.

Speaker 3 These court fights are still ongoing. There's still a lot of work to get more of those water rights back.

Speaker 3 But there's another problem, and this is something that Whitney noticed in the farmers markets.

Speaker 8 When we went to sell it, not a lot of consumers wanted to buy it.

Speaker 4 Tarot may be revered and traditional and tasty and healthy, but it's kind of a lot of work. The scratchiness and the lengthy cook time, who has time for that anymore?

Speaker 1 That's kind of what was the inspiration for creating all these value-added products.

Speaker 8 And so we've created products that are just really easy for the consumer to eat the tarot a lot easier and in more

Speaker 3 adaptable ways that they're familiar with. These young tarot farmers wanted to create new products they can sell at farmers markets.

Speaker 3 Whitney, Jake, and Winsom started recipe testing over just the past couple of years, and they had cooked up some products for us to try.

Speaker 4 We tried tarot hash browns, which were excellent, and tarot cassava tortillas, which I liked so much I brought a couple packets home to LA where you can already get a lot of good tortillas.

Speaker 4 And then we tried their take on a more traditional preparation: little fried squidgy taro squares made from the poi paste before you add water.

Speaker 5 And what we do is put that in a little Tupperware and then put it in the refrigerator, it gets nice and sort of solidified. And what you guys are going to taste today is us slicing that up and

Speaker 5 frying it in a little coconut oil.

Speaker 5 We'll just let it get nice and crispy on the outsides, and then it's going to be nice and sort of like almost like a poi on the inside it's really delicious

Speaker 5 and then we like to serve it with a little bit of um salt and nutritional yeast and cinnamon and sugar we'll do a sweet and a savory version it's kind of like a hawaiian donut

Speaker 1 all right those are crisping up nicely

Speaker 4 We started with the savory version, which was salty and of course deliciously squidgy.

Speaker 7 Yeah. Wow, that's good.

Speaker 4 I mean, I think most much of the flavor is coming from the salt and the yeast. Sure, but I feel like it has a really nice texture.

Speaker 3 And then we tried the sweet ones. They reminded me of mochi squares, and I was really into them.

Speaker 4 It's kind of like a donut now.

Speaker 3 Totally like a little donut.

Speaker 1 Yeah.

Speaker 4 Delish. Whitney, Winsom, and Jake have been recipe testing all pandemic.

Speaker 4 These new tarot products are all pre-prepared, packaged, and ready to stick in the freezer and then warm up on the stove and eat.

Speaker 4 They've started including these tarot treats in their CSA boxes and selling them to some of Bobby's customers. And they also have a very popular taco stand at the local farmer's market.

Speaker 3 And Bobby's a fan. He's not such a traditionalist that he can't appreciate what the next generation is doing.

Speaker 1

Because we're just so used to eating boy all the time. Just boy, then you get like that flatbread they make with the collar.

They make all kinds of products, desserts, and oh man, all kinds.

Speaker 1 I like it, it's good. And what is really good about that is that it's more palatable to a greater number of people.

Speaker 4 This renaissance of taro, it's part of a larger renaissance in Hawaiian culture. And Sheldon told us that bodes well for both Hawaiian cuisine and Hawaii's future.

Speaker 10 The Hawaiians understood the connection of the land and the sea better than anyone else.

Speaker 10 And it's us understanding that and celebrating and taking care of that that's gonna be key to moving forward for our future of Hawaii.

Speaker 3 Thanks this episode to Sheldon Simeon, Papi Paia, Scott Fisher, Noah Cuckueba Lincoln, and Winston Williams, Jay Co Oga, and Whitney Cunningham.

Speaker 3 We have links to their restaurants, organizations, and farms on our website, Gastropod.com, as well as photos from our Hawaiian tarot adventures.

Speaker 4

And as always, thanks to our awesome producer, Claudia Guide. We'll be back in two weeks with another new episode for your listening delight.

Till then.

Speaker 4

You're basking on a beach in the Bahamas. Now you're journeying through the jade forests of Japan.

Now you're there for your alma mater's epic win.

Speaker 4 And now you're awake.

Speaker 1 Womp, womp.

Speaker 4 Which means it was all a dream. But with millions of incredible deals on Priceline, those travel dreams can be a reality.

Speaker 4

Download the Priceline app today, and you can save up to 60% off hotels and up to 50% off flights. So don't just dream about that trip.

Book it with Priceline.