The Hangover: Part Gastropod

Learn more about your ad choices. Visit podcastchoices.com/adchoices

Press play and read along

Transcript

Speaker 1 My name is Adam Rogers. I'm a senior correspondent at Wired, and I'm the author of a book called Proof the Science of Booze.

Speaker 1 This is about a level of enjoyment and a high level of interest, but it's not about addiction, which is a huge problem with alcohol.

Speaker 1 And it's really, it's not about consumption to excess, except in one specific case, which was this chapter on hangover, because of two things. First, I knew that it was everybody's question.

Speaker 1 Whenever I told anybody I was writing a book about the science of booze, they would say, what about hangovers?

Speaker 1 And also, it was a honey trap because I knew it was popular and I knew it was going to be the thing that people would want to talk to me about. So it has succeeded.

Speaker 1 Yet again, the jaws of my trap have snapped shut around your excellent podcast.

Speaker 2 We were lured in by Adam's hangover honey trap, and so we're doing the same to you. Welcome to the Hangover Honey Trap episode of Gastropod.

Speaker 3 I'm Nicola Twilley, and I never thought I'd say that sentence.

Speaker 4 And I'm Cynthia Graver. And of course, Gastropod is the podcast that looks at food through the lens of science and history.

Speaker 4 And so while hangovers aren't food per se, they are the result of a food or, you know, a beverage.

Speaker 2 But what are they? What is the medical basis of this unfortunate condition? And more importantly, can science do anything about it?

Speaker 2 I'm picturing labs full of scientists working on the hangover, trying to come up with a cure the way they do for cancer.

Speaker 4 Could the cure be hidden in one of the many traditional hangover recovery recipes you listeners sent us?

Speaker 4 But also, we're using hangovers as a honey trap themselves to lure you in so we can talk about what was, until recently, the most overlooked of all the organs, the liver.

Speaker 2 You say overlooked, Cynthia, but the liver used to be more important than the heart. It was so powerful that if you asked it the right question, it could predict the future.

Speaker 3 Forget Tarot.

Speaker 2 What you need to know what's going to happen next is a juicy slab of organ meat.

Speaker 4 But to bring us back to food and drink, what role does the liver play in hangovers? And could we somehow unlock its secrets to help prevent splitting headaches and nausea?

Speaker 2 All my fingers and toes are crossed. This episode is all that, plus, we explore the weird but huge phenomenon of hangover drinks in Korea.

Speaker 4 A quick note: as Adam said, alcohol abuse and addiction is a really serious issue, and it's something we've covered before on Gastropod.

Speaker 4 It's not the focus of this episode, but if alcohol is a problem for you, we will be talking about drinking.

Speaker 2 This episode was made possible thanks to generous support from the Alfred P.

Speaker 2 Sloan Foundation for the Public Understanding of Science, Technology, and Economics, as well as the Burroughs Welcome Fund for our coverage of biomedical research

Speaker 4 like you said adam rogers wrote a book about booze and of course you can't write a book about booze without writing about booze to access the hangover the morning after the night before and you sort of know when it's coming like you you know you wake up and before you've done the full inventory you feel the fear like oh this is going to be a bad day This is going to be bad.

Speaker 4 This is really what a hangover is. It's a description of a feeling.

Speaker 1 Well, one of the fascinating things about hangovers is that the symptomatology varies widely from individual to individual.

Speaker 1 It's one of the things that makes them hard to study, but some of the things that are at least common enough that people will recognize headache, sensitivity to light and sound, kind of generalized malaise, a feeling of exhaustion, inability to concentrate, inability to focus, gastrointestinal upset of various kinds, diarrhea to stomach ache to heartburn.

Speaker 1 and kind of a just a sense of like confusion that goes beyond just being tired, sort of inability to operate complex machinery, as the label might say.

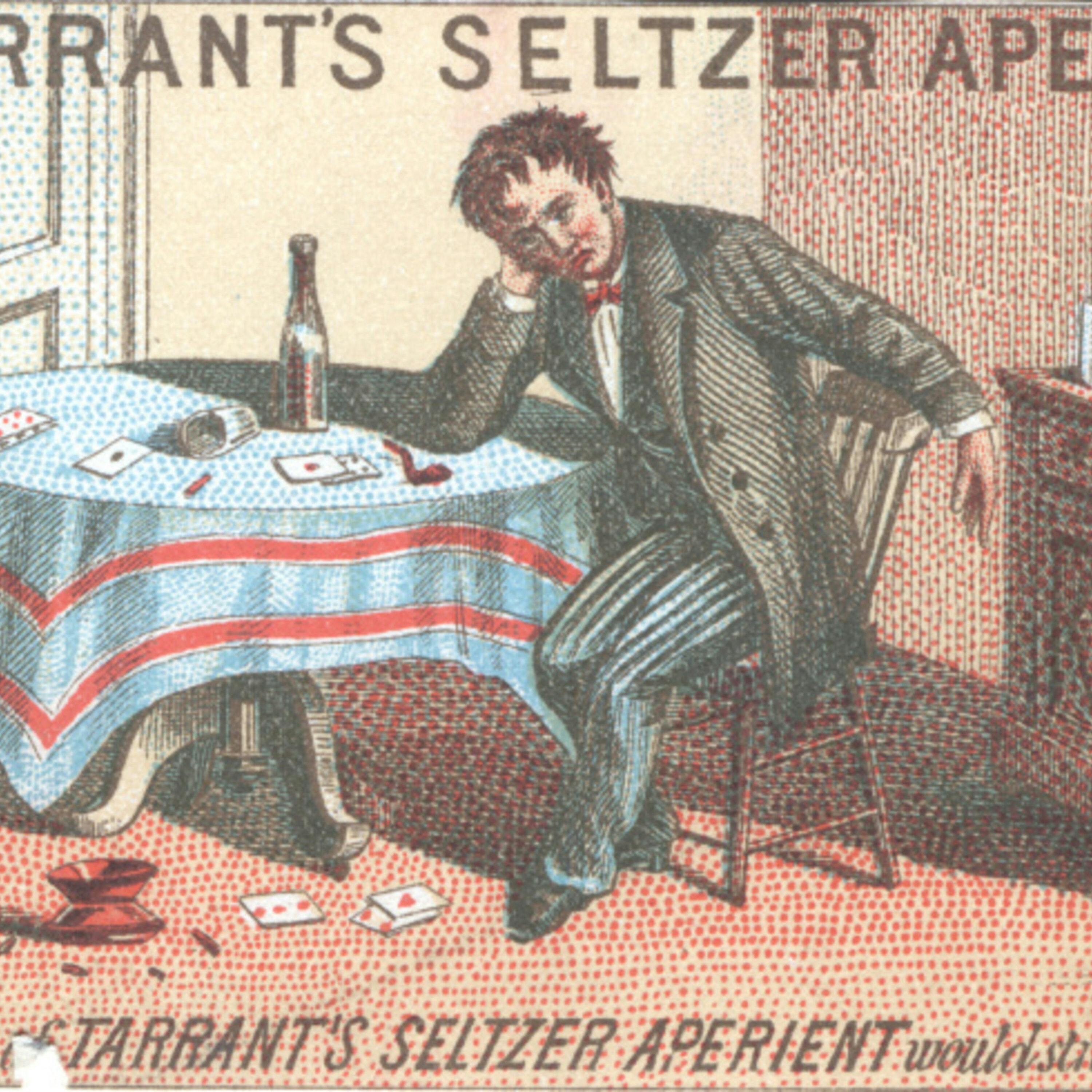

Speaker 2 This all sounds far too familiar from my own personal history, but what is the actual history of this most horrible of sensations?

Speaker 1 As long as we've had alcohol, which is, you know, really since human beings consumed anything made from agricultural products because things ferment spontaneously, people have experienced the bad outcomes of overdoing it.

Speaker 4 Hangovers show up in a number of historical documents. One of the oldest and most terrifying is from the Odyssey.

Speaker 4 And in case you were curious, scholars think the Odyssey probably is nearly 3,000 years old.

Speaker 1 One of the names for hangovers is Alpinor's Syndrome, because of a character in the Odyssey who,

Speaker 1 the night where Odysseus and his crew are going to escape from Circe's Island, they know they're leaving the next day, and so they have a huge party. And the next morning, Alpinor is so hungover.

Speaker 1

He wakes up and he's so hungover that he falls off of the building, the roof of the building where he's been sleeping and he dies. And they leave him behind.

They don't notice that he's gone.

Speaker 1 And Odysseus feels all kinds of guilt about that later and encounters him in the underworld at one point and has to apologize. It's like the most mortifying, literally mortifying kind of hangover.

Speaker 1 You know how embarrassment is one of the symptoms where you're like, I don't remember a lot of what happened last night, but I realize I behaved poorly.

Speaker 4

The experience of this, minus the falling off the building and the encounters in the underworld. Otherwise, it's both universal and ancient.

But the word hangover didn't appear until the early 1900s.

Speaker 4 Before that, it was called some rather evocative phrases: morning fog, gallon distemper, bottle ache, crop sick, bust head.

Speaker 2 The first recorded use of the word hangover is in a humor book from 1904. It was called The Foolish Dictionary.

Speaker 2 And in its definition for the word brain, it says, usually occupied by thoughts and ideas as an intelligence office, but sometimes sublet to jag, hangover, and company.

Speaker 4

And here we are, stuck with hangovers. The word apparently really picked up around World War II.

I can't imagine why people were doing a bit more drinking at the time.

Speaker 1 There's a clinical term that gets used sometimes, which is more recent, vesalgia, which just means like the pain and regret from the night before, essentially, but it's rarely employed, partially because there's so little actual clinical study of hangover in the first place.

Speaker 2 Yeah, my vision of a lab full of scientists working on the hangover, Adam says that's not the case at all.

Speaker 1

There are a handful of researchers who study hangover, and it's not usually their main thing. They're very few.

It's very hard to get grant money for it. It's kind of looked down on in a weird way.

Speaker 1 And nobody who I talked to was sure of why that would be, except because there's some kind of moral panic about it.

Speaker 4 Studying the hangover gets tied up with a lot of value judgments. Like maybe if you find a cure, people would drink more because they wouldn't have to deal with the pain the next day.

Speaker 1 So you can get a lot of money and rightly so to study addiction, to study the consequences of drunk driving, driving under the influence, all the bad outcomes that really are bad for alcohol societally.

Speaker 1 But there's a perception, I think, that if you're looking at hangover, you're studying not the good outcomes, but like you're trying to fix one of the bad things that's supposed to keep people in check.

Speaker 2 Adam says there is a small hangover research group, and they do occasionally meet up and share results.

Speaker 1 They all present some, what remain, even years after I looked at it, preliminary results with small numbers of people.

Speaker 1 There's still some controversy over what the clinical definition of a hangover even is, much less how to objectively verify with lab tests whether somebody is hungover.

Speaker 4 This is a huge part of the problem when it comes to science. How do you measure all of these horrible feelings you get when you're hungover?

Speaker 1 I don't think there's an objective metric for the fatigue and confusion and kind of brain cloud that you get when you're hungover.

Speaker 2 We can measure how drunk you are. Even before breathalyzers, people had developed ways to evaluate that.

Speaker 1 In the early days of alcohol research in general, one of the metrics for how impaired somebody was was how fast they could type compared to when they weren't impaired.

Speaker 1 But it's harder to find those proxy measures with hangover, especially because the symptoms are so different from person to person.

Speaker 1 You know, even just like the fact that mine tend to sit in my gut while other people's tend to be headache. Like, are those the same syndrome even? The symptomatology is totally different.

Speaker 1 And because the physiological measures are so hard to find, that becomes a very difficult thing to study in addition to the societal pressures against studying it.

Speaker 4

Researchers have developed a scale to quantify these symptoms. It's called HSS for, yes, hangover symptoms scale.

It's also pretty subjective. There's a sliding scale for a dozen symptoms.

Speaker 4 They include unpleasant things like clumsiness, dizziness, sweating, shivering, stomach pain, nausea.

Speaker 2 I love the idea that science could help you know whether you're having a truly dreadful hangover, like a 10 on the hangover scale. That would for sure make the whole experience so much better.

Speaker 4 So it's tough to measure the ways that a hangover affects you, or me, or anyone else. But what about figuring out why we get them in the first place?

Speaker 4 Have scientists made any inroads into answering that question.

Speaker 2 Right, that is a question that I can actually see being useful information. I mean, it's one thing to be able to measure how terrible you feel.

Speaker 1 I also wanted to know why, you know, that happens to you and you're like, well, this, I feel terrible. What's going on here?

Speaker 1 You know, if you have any interest in kind of the science of the universe or you're interested in medicine and health and science,

Speaker 1 how did that happen?

Speaker 4 There is one thing that scientists know for sure. They know the liver is involved.

Speaker 1

The liver is kind of the place that makes the stuff that the body uses to process. the alcohol.

And people will kind of casually say, well, you know, alcohol is a poison, it's a toxin.

Speaker 1 And that's sort of not exactly right. You know, it's not an like, it's not an alkaloid plant toxin.

Speaker 2 The key ingredient in alcohol is a chemical called ethanol. That's what the yeast makes when it eats all the sugars in the grapes or malt or whatever.

Speaker 2 And ethanol gets broken down by enzymes in your liver.

Speaker 6

So the liver is an organ. It's about the size of a football.

And it sits in your belly tucked underneath your right rib cage.

Speaker 6 And so if you take a deep breath in, you can kind of feel it like poking out there from your ribs.

Speaker 4 Sangira Batya is a biomedical engineer at MIT and pretty much a superstar in the bioengineering and liver worlds.

Speaker 4 She's the first person to create tiny little functioning livers, like a liver on a chip, that can be used to study all sorts of things about this organ.

Speaker 6 Simplistically, when people think about organs, you know, they say like the heart is a pump, the kidney is the filter. People say about the liver that it's like a factory.

Speaker 6 So it takes in lots of things and spits out lots of things and it does a lot of metabolism.

Speaker 2

A lot of researchers think the heart is exciting. It's this pump that keeps our body going.

Or the brain, that mysterious seat of consciousness. But Sangeeta chose to study the factory.

Speaker 2 She picked the liver.

Speaker 6 You know, I think about it sometimes, it's sort of like falling in love. Like, you don't really know why.

Speaker 6 But I sort of met the liver in the first year of my graduate school when I was a graduate student and was fascinated with it.

Speaker 4 At the time, she was pretty lonely in her love.

Speaker 6 So when I started working on the liver, which was in the 90s, it's like not a popular organ

Speaker 6 in the U.S. for I think lots of almost social reasons in terms of like the way that you can damage to your liver is seen to be historically a bit self-inflicted.

Speaker 6 And as a result, a lot of people didn't study it.

Speaker 2 The liver might not have been fashionable in the 90s, but it definitely was further back in the past. Sangita would have had plenty of company in her liver appreciation society thousands of years ago.

Speaker 6 It also has like a really rich kind of mythological history. The liver, it used to be said that before, you know, we say now like you get a broken heart.

Speaker 6 In some cultures, the translation is actually that you have a burned liver. So it used to be like the center of like all of the different streams of life.

Speaker 7 The liver was considered the site of the soul and the central place for all forms of mental and emotional activity.

Speaker 2 Marie Laurence Ack is a professor of ancient history at the University University of Picardy in northern France.

Speaker 7 Actually, liver is an organ full of blood, and it is bigger than the heart. Many ancient people thought that the mind of the gods was reflected in the liver of the animal.

Speaker 4 This idea that the liver was so critical that the mind of the gods was reflected in an animal's liver, it led to what's called haraspicy.

Speaker 4 It's like the ancients were using the liver as a magic eight ball.

Speaker 6 Yeah,

Speaker 7 aerospicy is a form of divination by the expansion of the livers of sacrificed sheep for gods. People thought that the gods sent messages to decipher with the help of those sayers.

Speaker 2 Marie Laurence told us that this fortune-telling technique, asking questions that the gods would then answer through an animal's liver, it seems to have first emerged in Babylonia and Assyria and then spread to ancient Greece.

Speaker 4 We no longer know exactly how they read the liver. There are a couple of murals that survived in Italy that depict Harospicy.

Speaker 4 You can see a soothsayer or fortune teller holding the liver of an animal in his hand and examining it.

Speaker 2 There are also a couple of model livers that give us some clues as to what the soothsayer was looking for.

Speaker 2 There's one bronze liver that was found at an archaeological site in southern Italy that had different constellations marked on different parts of the liver, so you could see which section corresponded to which god.

Speaker 2 A soothsayer would also look at the shape and size and even the color of the liver.

Speaker 7 When the liver was black, it was a bad sign.

Speaker 4 A black liver does sound like a bad sign, at least for the animal involved.

Speaker 3 Not so sure about the gods.

Speaker 2 We were curious what the liver could tell you. What kinds of questions would you even ask a liver?

Speaker 7 The response of the liver could be yes or not to simple question on the state of mind of the gods. For example, were the gods angry, were they satisfied?

Speaker 7 A good reader of the liver could predict the response of the god, yes or no, and it could predict also illness, death, victory, or defeat.

Speaker 4 Marie Laurent says there is one story of liver divination that has lasted through the ages.

Speaker 4

A liver soothsayer named Spirina sacrificed a bull that apparently didn't have a heart and had a malformed liver. This is a story that William Shakespeare included in his play Julius Caesar.

Speak.

Speaker 8 Caesar's turn to hear.

Speaker 2 Spirina took this dodgy liver as a bad sign, which seems fair.

Speaker 2 And then, again, according to Shakespeare, who definitely wasn't there, he uttered the immortal lines, Beware the eyes of March, and warned Caesar that his life was in danger for a period of 30 days,

Speaker 7

which ended on March 15th. And Julius Caesar was assassinated by a group of senators on that day.

The prediction was right.

Speaker 4 That's one win for Team Liver. Unfortunately, despite this apparent successful fortune-telling event, Haraspicy died out when what's now Italy became a Christian country.

Speaker 2 But don't worry, if you would like to consult a liver today, you can. There is a Harrispex, which is the name for someone who Harrispic is.

Speaker 2 She uses chicken livers because they're easier to get hold of, and she lives up the street from my old neighborhood in Brooklyn.

Speaker 4 A Haruspex in Brooklyn? I'm shocked.

Speaker 2 So, Harrispicy may or may not accurately foretell the future, but one of the other major ancient myths about the liver is really true.

Speaker 6 You know, the myth of Prometheus is that he stole fire from the gods, and his punishment was that he would be strapped onto this rock and exposed to the elements and every day an eagle would come and eat at his liver.

Speaker 6 That was the punishment. What the hepatology community infers from that is, oh, like, look, even then they knew that the liver regenerates.

Speaker 6 Because the only way this myth works is that the liver is regenerating and the eagle eats it and the liver is regenerating and the eagle eats it.

Speaker 4 And this is actually one of the reasons the liver is having a comeback today. The liver is the only organ other than our skin which can indeed regenerate.

Speaker 4 If you lose a part of your liver, it'll just grow back. The ancients got that right.

Speaker 2 On a more day-to-day basis though, the liver really is a factory like Sangeeta said. Raw materials go in, the liver does stuff, and finished products come out the other side.

Speaker 4 Quinton Smith is a researcher in Sangeeta's lab.

Speaker 9 So the liver aids in something called glycolysis where it breaks down for example carbohydrates in our meals. So we have starches, we have sugars that are processed by the liver.

Speaker 9 The liver also breaks down fats. It also breaks down proteins.

Speaker 4 The liver is breaking down fats and carbohydrates and alcohol. There are enzymes in the liver that break down ethanol and turn it into something called acetaldehyde.

Speaker 9 So if we look at acetaldehyde, it's like almost like formaldehyde, which is

Speaker 9 a very toxic substance that people might be more familiar with. This is actually can cause like an inflammatory response.

Speaker 1

And it's possible that that maybe is a thing that causes the symptoms of hangover. Problem is that's very hard to detect.

It's really evanescent.

Speaker 2 Adam's point is that the acetaldehyde is hard to measure because it really isn't around for very long.

Speaker 2 The liver keeps pushing it along the factory line and turns it into acetate, which isn't as toxic. It's essentially the same as the acid in vinegar.

Speaker 4 But so we can find a clue to how acetaldehyde affects our headaches and nausea by studying people who can't get rid of it.

Speaker 1 People who come from countries in Asia tend to make less of or none of one of the key enzymes that breaks it down.

Speaker 1 So they sort of jump right to hangover from a drink rather than feeling an intoxication.

Speaker 2 And actually, scientists have used that insight to create a medicine that is prescribed to prevent alcohol abuse.

Speaker 6 And the way that medicine works is it inhibits these pathways that we've been talking about. And patients would get this feeling of an instant hangover and it is a deterrent for drinking.

Speaker 6 So that is an actual medicine.

Speaker 2

Thanks, science. You've made a medicine for an instant hangover.

Now, how about one to cure it?

Speaker 4 Part of the problem when it comes to trying to cure the hangover, at least when it comes to ethanol, is that ethanol isn't just going through the liver, there's also some that gets stranded in the blood, and so from there it ends up pretty much everywhere.

Speaker 1 Ethanol is a very small molecule that crosses the blood-brain barrier, which is unusual for most molecules that the body usually keeps anything except oxygen and blood out of the brain.

Speaker 1 Ethanol gets in there.

Speaker 4 It's not super clear exactly what it's doing in there.

Speaker 2 Adam says, because it's in your blood, ethanol also gets into your kidneys and messes with them. It gets into the lining of your stomach and intestines and gives you a stomach upset.

Speaker 4 So in theory, any hangover remedy should deal with the effects of ethanol, but it's not the only problem. Scientists have a lot of theories about what else might be contributing to our hangover pain.

Speaker 3 Well, right.

Speaker 1 So one of them is that alcohol suppresses a hormone called vasopressin or the anti-diuretic hormone. And that's a hormone that keeps you from peeing too much.

Speaker 1 So alcohol has a dehydrating effect, but if you are hydrated, you still get hungover.

Speaker 4 So dehydration might add to your morning misery, but it's certainly not the only cause.

Speaker 2 Another theory blames something called congeners.

Speaker 1 Congeners are everything that's in a drink that's not the alcohol or the water.

Speaker 4

Vodka, as you all probably know, is clear. It's technically just ethanol and water.

But now picture whiskey or beer or basically anything other than vodka.

Speaker 4 It has all sorts of other things in it that give it color and flavor. Those are called congeners.

Speaker 1 So there's all these other chemicals that are in there. And there were some hypotheses that said, well, those congeners, maybe people are allergic to some of those.

Speaker 1

So people will test, like, okay, well, you over there drink vodka, you drink brandy, you drink whiskey. Who gets the worst hangover? These are terrible studies.

Terrible, I feel bad saying that.

Speaker 1 These are not great studies.

Speaker 2 Like a lot of hangover research, these studies were done on a super small group of people, and the measurements all seem to be rather subjective.

Speaker 1 In some of them, people reported having worse hangovers with, say, brandy than they would with vodka, but you still get hungover from the vodka.

Speaker 2 So congeners might be part of the problem, but again, they're definitely not the only cause of a hangover.

Speaker 4 On to the brain hypothesis.

Speaker 4 Alcohol is known to be a depressant, and so there's a theory that your brain creates a bunch more receptors to pick up the slack when the brain's activity is depressed from drinking too much.

Speaker 1 But then once the depression is gone, you still have a lag of when the brain hasn't cleaned out all of those kind of receptors that it built specific to that task.

Speaker 1 When you snap awake and you feel bad and you're like, you know, you're too hot or you're too cold and you don't feel good and you stumble to the bathroom, all that stuff.

Speaker 1 That might just be that like the brain has recalibrated itself to deal with. too much alcohol, but now there isn't too much alcohol, but the brain's still recalibrated.

Speaker 1 So now you have all kinds of the hangover problems. That's a hypothesis.

Speaker 4 It might be part of why your focus and energy are so messed up, but there isn't any good evidence yet to support this theory.

Speaker 2 Yet another hypothesis is that because alcohol messes with your pancreas, that organ can't handle all the sugar in your mixes as well as it normally would, and so your blood sugar gets all out of whack, and that's part of the hangover feeling too.

Speaker 2 But Adam says that's also not probably the main cause.

Speaker 1 But that's really true with a lot of hangover research. The answers to almost every question that I try to ask are like, well, it's this, but that's probably wrong.

Speaker 4 So far, based on all the not super strong hangover research to date, the liver seems to play the biggest role in hangovers.

Speaker 4 Sankita and Quentin say that acetaldehyde does cause an inflammatory response, and your liver does make acetaldehyde as it breaks down ethanol.

Speaker 2 Even though that acetaldehyde is not normally around for very long because the liver keeps on breaking it down.

Speaker 2 So we don't really know exactly why it would trigger such a horrific response, but still.

Speaker 1 So that's the one that seems like the best account that people have so far. And the idea there is that if you think about it, the symptoms of a hangover feel very much like the flu, right?

Speaker 2 I mean, they kind of do. And so this theory goes that that's because after you've consumed too much alcohol, your immune system is going into overdrive, trying to fight off inflammation.

Speaker 2 The same way it would if it was fighting the flu.

Speaker 1 So a lot of hangover symptoms look like inflammation, and in fact, they probably are.

Speaker 4 So long story short, while inflammation seems to be maybe the primary cause, nobody's totally sure exactly why we end up with all of the nausea and dizziness and aches and pains, but it doesn't mean people haven't been trying to fix hangovers for thousands of years.

Speaker 2 We decided to mine the wisdom of gastropod listeners for this episode, thinking that maybe some of you perchance might have had a hangover in your lives and thus might know a cure or two.

Speaker 2 Turns out that having another drink is a concept that's popular worldwide.

Speaker 10 Hi, Gastropod.

Speaker 10 So in Mexico, we have

Speaker 10 some

Speaker 10 remedies. So some people cure hangovers here with even more beer.

Speaker 12

Hi Cynthia, hi Nicola, this is Anja from Germany. Here people will tell you to chug a counter beer which literally translates to counter beer.

It's the same idea as hair of the dark I guess.

Speaker 2 I mean if you think about it one obvious way to avoid a hangover is to never stop drinking.

Speaker 1 That's right. Good plan.

Speaker 1 Here's what I'm gonna do. I'll just never be sober again.

Speaker 2 Stay drunk. What you don't think that's a good plan?

Speaker 1

Here's the problem. You develop tolerance.

So you just, you have to keep upping the ante of your alcohol consumption.

Speaker 1 That's the problem with that plan.

Speaker 4 This is actually one of the oldest known hangover cures described, at least in Western traditions.

Speaker 4 The ancient Greek comic poet Antiphones is, as far as we know, the first person to have coined the term the hair of the dog in reference to the hair of the dog that bit him and his drinking buddies the previous night.

Speaker 4 Adam says this approach has been popular till, well, till today.

Speaker 1 There were a whole set of very specific um cocktails that were expressly designed to be breakfasty hangovery remedy things with bloody mary is one of them but basically any of the drinks that had an egg in them were most likely pick-me-ups designed to to make you feel better if you had a hangover there's one that i love it's a drink i still love now called the corpse reviver number two that's not about anything mystical or Lovecrafty and the corpse in that case is the person who has the hangover.

Speaker 1 It's a drink meant to revive them.

Speaker 4

Totally delicious cocktail. I'm a fan.

Not sure that's the best way to deal with a hangover.

Speaker 2

We did some advanced data analysis on all your responses and some key themes emerged. Pickles and also soupy broth things.

Those seem like popular hangover remedies for a bunch of you.

Speaker 13 Hi, my name is Veronica. I come from a Polish background and our cure for hangovers is dill cucumber juice.

Speaker 2 So lots of vinegar, dill, garlic.

Speaker 13 And despite the horrified looks I get from my partner when I go in down after a big night, I find that it works and it's actually quite delicious.

Speaker 5 Thank you. Bye.

Speaker 14 This recipe is called Lagobalid.

Speaker 14 And L'Agobolid in Occitan means

Speaker 14

boiled water. So it's a very simple recipe.

Perfect for hangover. In this recipe, you cut much, much garlic.

Speaker 14

Again, with the garlic, always the French with the garlic, into pieces. You boil the garlic in water with some thyme.

Then you pour this the soup onto a big slice of buttered country bread.

Speaker 4

That sounds delicious. A lot of you also pointed to super spicy foods and said they'd help you sweat out everything from your system.

And then there were a lot of votes for fatty foods.

Speaker 8 Hi Gastropod.

Speaker 8 Uh when I was a student we believed that there were three things that could cure a hangover.

Speaker 8 The first one was to drink a pint of milk before you actually went out for a drink.

Speaker 8 This was to line your stomach. The second one was to have a greasy kebab

Speaker 8 just as you finish the session.

Speaker 8 And then there was the full English the morning after.

Speaker 15 Hello, gastropod. This is Linda from Houston, Texas.

Speaker 15 I am actually a certified toxicologist, but I've known for a long time that the best cure for a hangover is none other than a large sprite and a large French fry from the Golden Arches of McDonald's.

Speaker 2 I mean, if a certified toxicologist says it, it must be true. I will say I have had the full fried English breakfast many times after a night out.

Speaker 2 Eggs, bacon, sausage, fried bread, and baked beans all drowned in some lovely gloopy brown sauce. It does feel good in the moment, but it can backfire.

Speaker 3 I have to admit, as a hangover cure, that sounds really painful.

Speaker 2 A fried breakfast is delicious, but you do have to have a stomach of iron, which is not necessarily the case the morning after a big night out.

Speaker 2 In his book, Adam has a whole list of remedies that people have claimed work.

Speaker 2 There's something called peritinol, which is a vitamin B6 analog, and a pill called Liv52, which has a bunch of Indian plants in it and is based on Ayurvedic medicine, and then some extract of prickly pear, which is supposedly anti-inflammatory.

Speaker 1 People make a lot of these cases, but there's almost never,

Speaker 1 you know, there's almost never a large-scale randomized controlled trial with a lot of people behind any of this stuff.

Speaker 1 They are claims based on anecdotal evidence and you know mouse studies and stuff.

Speaker 4 Those were all crappy studies, so Adam decided to do a very scientific study of his own and try these out on some friends after a hard night boozing.

Speaker 1 My group experiment was a terrible, a catastrophic failure, but I had the best of intentions.

Speaker 2 The intention was that they would get drunk and then each of them would take a different remedy and report back.

Speaker 1 I don't want to call it data. Would report a response, let's say.

Speaker 4

So a couple friends came over to Adam's house. He made them all sorts of drinks.

He was pretty well set up at the time because it was right in the middle of his research on his book about booze.

Speaker 4 They got completely hammered.

Speaker 1 And then, like, I sent everybody home safely and they all sort of reported in saying like, yes, that was the worst hangover I ever had. And maybe it helped a little bit and maybe it did.

Speaker 1 I can't really tell. I woke up with one of the worst hangovers I'd ever had and took a handful of everything that I had in the house.

Speaker 1 So like I got just, I took like a handful of all of the remedies that I had in one gulp and then went back to bed and woke up at about three with a bad hangover.

Speaker 1

I would characterize that as an unsuccessful experiment. What did I learn? Don't do that.

That's what I learned.

Speaker 2 Honestly, Adam says one of the best things is probably something you have every morning, not just the morning after. And we have a listener who agrees.

Speaker 11 Well, not surprisingly, in Italy, the main cure for hangover is espresso.

Speaker 1 That's the thing that's going to make you feel better because it, you know, caffeine works, man. Caffeine's great for making you not feel as fatigued and improving your ability to focus and stuff.

Speaker 4

But really, we should be able to do better than this. There's got to be a cure out there somewhere.

And as it turns out, we have someone on our team, Gastropod Fellow Sonia Swanson.

Speaker 4 She's lived in a country where they are famous for hangover cures.

Speaker 11 I lived in Korea for about seven years, right after college, and my mom is Korean, so there's this kind of drawback that I had been feeling for a long time, and I ended up staying there for quite a while.

Speaker 11 But while I was there, as one does in one's early and mid-20s, you go out and you drink, and then sometimes you have a hangover in the morning.

Speaker 2 Sonia says there are a lot of hangover cures in Korea because there are a lot of hangovers there.

Speaker 11 Yeah, you know, well, alcohol has definitely been a part of Korean like traditional culture for a long time.

Speaker 11 Like they have these traditionally brewed like rice alcohols that are an important part of like holidays and ancestral rites, welcoming guests at weddings and things.

Speaker 11 I mean still at some ancestral ceremonies like at one that my family does for my grandmother called Chesha, we take a glass of rice wine and we circle it around some incense before pouring it on her grave.

Speaker 4 Sonia told us the culture around drinking changed over the past century.

Speaker 4 Alcohol production became industrialized when Japan occupied Korea in the first half of the 1900s, and that meant that the traditional Korean rice alcohol soju became really cheap.

Speaker 11 So you can get a 12-ounce green bottle of soju today and it'll be less than $2 from the convenience store.

Speaker 2 Of course, there are plenty of higher-end drinks available and being consumed in Korea too. Frankly, Sonia said there are plenty of all kinds drinks being consumed on a pretty frequent basis.

Speaker 11 You know, honestly, drinking culture is really pervasive. I mean, there's a side of it that's kind of delightful.

Speaker 11 I mean, I remember going to picnics where we would order fried chicken and have cold beer by the side of the Han River. And we'd be out at these wonderful, tiny little, like, cozy bars.

Speaker 11 And we'd sip soju with these yummy side dishes inside this pojang matcha, which is like a tent that they set up on like streets in the wintertime.

Speaker 11 There's parts of it that are just really wonderful and delightful. But the pervasiveness of drinking has also infiltrated work culture.

Speaker 11 So South Korea has a really intense and kind of notorious office work culture.

Speaker 11 And there is this afterwork event called hesik, which is kind of an obligatory party, not so fun, because it involves like this kind of hazing and an intense pressure to drink.

Speaker 11 So it's all part of this like very like work hard, play hard office culture.

Speaker 4 And all this drinking comes at a literal price. Even in the US where the drinking culture isn't quite as pervasive, it's a big deal.

Speaker 1 There are some estimates that range into the billions of dollars of lost productivity, which is a euphemism for people who call in sick, you know, the next day. And that's just in the U.S.

Speaker 1 Places that are heavy drinking cultures, this is a consequence of that. They'll have lost wages, lost work hours, people who mess up their work because they're hungover, all that kind of stuff is

Speaker 2 a real consequence. And so, in these places that do have heavy drinking cultures, there's also been a lot of effort and ingenuity devoted to avoiding the resulting hangovers.

Speaker 4 Like in most countries, Korea did have traditional hangover remedies.

Speaker 4 Sonia told us about one that included a bunch of herbs like arrowroot and ginkgo and pea flour, but the real boom in hangover remedies occurred as drinking got more popular.

Speaker 11 Over the course of the 20th century, a category of foods known as hejang, those started to gain popularity. So hejang is like this idea of like restorative post-drinking cure or hangover cure.

Speaker 11 And so this hejang kind of category is primarily, I would say, composed of maybe hot soups that you're supposed to eat in the morning. So the most famous of those is hejang kuk, which is

Speaker 11 it's like this really hearty stew. It's got like blood cake and fiddlehead fern and chili paste.

Speaker 2 Sonia told us this was a traditional breakfast for dock workers and night shift workers to eat on their way home.

Speaker 2 But when clubbing culture started being a big deal in Korea in the 60s, people who had been dancing all night would join them for a dawn bowl of stew with blood cake.

Speaker 4 Nourishing brothy soups caught on first, but then companies saw the huge market for hangover remedies and began selling all sorts of hangover drinks.

Speaker 11 This is basically

Speaker 11 a category of canned or small bottled beverages. You can actually buy these at the very same convenience stores where you can also buy the cheap booze.

Speaker 3 Smart move.

Speaker 11 And they're kind of a relatively new invention.

Speaker 11 They came to market in South Korea in 1992 with a drink called Condition.

Speaker 2 So they are really popular.

Speaker 11 In Korea, the hangover drink market grossed over $165 million in 2014, and it's growing. So globally, Korea and Japan lead the world market in hangover drinks.

Speaker 2 Sonia graciously offered to act as our guide to this glorious world of hangover drinks so we could do an experiment of our very own. But first, there was a problem.

Speaker 2

We had to get drunk in order to get a hangover. So Cynthia prepared for this call with a full-on headache and it is because she has been out all night getting completely wasted.

Cynthia was trashed

Speaker 2 and she, I want a round of applause for Cynthia's dedication to the cause. Thank you.

Speaker 3 Bravo.

Speaker 11 Bravo, Cynthia.

Speaker 4

Actually, the headache was a result of a stress-induced case of insomnia coupled with dehydration. No alcohol involved.

But aren't dehydration and sleep deprivation hangover symptoms?

Speaker 4 So maybe I did prepare. Well, Nikki, how about you? Are you prepared for today's discussion?

Speaker 2 I had two glasses of very nice white wine and then called it a night.

Speaker 3 So yes, is what you're saying.

Speaker 4 You're such a lightweight these days.

Speaker 2 So yeah, basically under the table. I mean, wow, they had to drag me to bed.

Speaker 3 Incredible.

Speaker 2 Even Sonia, our resident expert, let us down.

Speaker 11 I chickened out.

Speaker 11

I had most of a beer, but couldn't finish it last night. So most of a beer.

That's kind of where I'm at with the tolerance level.

Speaker 4 So we've had most of a beer, two glasses of white wine, and zero alcohol all in preparation for today.

Speaker 2 This is pathetic, and

Speaker 2 we should do better. Our listeners deserve better, honestly.

Speaker 4 But anyway, we couldn't get blood cake, so Sonia suggested another hangover breakfast soup that's made with bean sprouts and dried anchovies and garlic and scallions.

Speaker 2 But I am sorry to say we couldn't get it together to get half of those ingredients either. So it turned out I didn't, I only had a 250 gram package of bean sprouts.

Speaker 2 Also, I had mung bean sprouts, not soy bean sprouts, but it turns out they're more or less the same, I think, maybe, Sonia. Yeah.

Speaker 11

Oh, yeah, yeah, yeah. You can totally make soup with mung bean sprouts.

You're all good.

Speaker 4 So I am not so good, although mine still looks and smells beautiful because my grocery store was entirely out of bean sprouts. Zero sprouts of any kind in my grocery store.

Speaker 2 Who knew, right? And

Speaker 2 during COVID-19, people would be hungry.

Speaker 3 Everyone was hungover.

Speaker 3 Everyone wanted sprouts. Everyone wanted sprouts.

Speaker 4 So I know it's called bean sprout soup, but I'm considering it a beautiful

Speaker 4 fish, like a fish broth, you know. So we gave our various attempts at bean sprout soup a try.

Speaker 2 All right.

Speaker 2 I'm trying.

Speaker 3 Mm.

Speaker 4 That's delicious. Without the bean sprout, so I don't know about that tender bean sprout thing, but the scallions are very tender.

Speaker 2 The broth is freaking amazing.

Speaker 4 Yeah. Yeah, it's really, really good.

Speaker 2

Basically, we were fans. Hangover or no? That feels very restorative.

I feel restored.

Speaker 3

I wasn't even like hungover and I feel restored. Oh, good.

I feel great.

Speaker 4 I had a lot of that. That was good.

Speaker 11 So

Speaker 11 get ready for the world of hangover drinks.

Speaker 4

Hangover drinks. These were actually pretty hard to find in the U.S.

Sonia had to scour Koreatown in Los Angeles. She did manage to find three different versions and bought us each one.

Speaker 11 I actually got some funny looks from the checkout ladies at the Korean grocery store when I had a basket full of hangover drinks.

Speaker 3 Oh really?

Speaker 3 I love it.

Speaker 11 And then I quickly explained that I was like getting some for some American friends who wanted to try some. And then she nodded.

Speaker 2

You had to explain yourself. Throw us under the bus.

Why don't you, Sonia?

Speaker 3 Right?

Speaker 11 I had to. I had to.

Speaker 11 It was the disapproving auntie stare, and I couldn't deal. I couldn't deal.

Speaker 2 Sonia had found us a little can of tropical island-themed hangover drink that tasted like orange-flavored mouthwash.

Speaker 4 There was one written entirely in Korean. Luckily, we had Sonia to translate for us.

Speaker 2 And then a bottle of 808 Dawn, which Sonia told us is one of the most popular hangover drinks of all. This one has a very handsome gentleman on the front.

Speaker 2 Tell us about him.

Speaker 3 Who is he?

Speaker 11 Yes, I am guessing he must be the inventor.

Speaker 3 It says, oh, yeah, it says inventor

Speaker 11 under his portrait.

Speaker 2 I love this can. It's awarded Supreme Prizes,

Speaker 5 Cam Laude Invention and Supreme Gold Medal at the Invention New Product Exposition in Pittsburgh, which, as everyone knows, is

Speaker 3 the shisle. I love it.

Speaker 2 Ew, the smell smells like Marmite.

Speaker 4 Wow. Yeah, it smells a little marmitey, but a little like plummy, like a little dried fruity.

Speaker 11 Exactly like a Flintstone vitamin to me.

Speaker 3 Totally.

Speaker 2

Oh, that's disgusting. Oh, it's totally disgusting.

Way too sweet.

Speaker 4 We like the taste of only one of them, the one where the bottle is entirely in Korean, but two of them contained the same ingredient.

Speaker 11 So that would be Hovinia or I think it's Hovinia adulsis, is the oriental raisin tree. That's also another ingredient that is used in traditional Korean medicine.

Speaker 4 In traditional medicine, it has actually been used to treat both hangovers and liver disease.

Speaker 2 As it turns out, the oriental raisin tree contains a compound that I'm going to call DHM because it's much easier to say than its full chemical name.

Speaker 2 And DHM is being studied right here in my own backyard at the University of Southern California.

Speaker 11 And what they found is that DHM kind of triggers this enzyme that helps metabolize alcohol in the cells.

Speaker 11 And it kind of triggered this, like what they called a cascade of effects. So it kind of reduced inflammation and it, you know, helped process the alcohol more quickly.

Speaker 11

And then that kind of helped the liver, you know, repair itself more quickly. So it seems like at least in mice and cultured cells, DHM does have an effect.

on the hangover, or at least on the liver.

Speaker 4 Of course, this study comes with a boatload of caveats, as Sonia pointed out. The results are in mice and in cultured cells, not in humans.

Speaker 4 And anyway, who knows how much you'd need or how much is in any one bottle. So this is not settled science.

Speaker 2 But Sonia says, it's not like everyone who buys these drinks thinks the science is 100%.

Speaker 11 It's a little bit more of a,

Speaker 11 maybe a,

Speaker 11

I don't know how to explain. Like, maybe it just seems like a kind of a sure, why not kind of approach.

That's been my general impression.

Speaker 4 Sonia doesn't keep any of the bottles around herself.

Speaker 11 I think I'm just getting a little too old for any hangovers at all.

Speaker 4 So I'm going to go ahead and get a little bit of a- So your cure for hangovers is not to get them in the first place.

Speaker 11 Yeah, to do my best not to, for sure.

Speaker 2

This is also the conclusion I have arrived at after much suffering. But sometimes accidents happen.

And because we love you, dear listeners, we don't want to leave you entirely without hope.

Speaker 2 So here's the best remedy science currently has to offer.

Speaker 1 There was a pretty good study a few years ago where they, again, they took those hapless

Speaker 1 but drink-poor poor postdocs took them to a lab made them get really drunk then the next day gave them a kind of nuclear-powered anti-inflammatory called clotem you can't get it in the United States but it's used to treat migraine again another set of symptoms that look a lot like hangover or vice versa and and had a really good effect and so there are people now who are looking at using combinations of various anti-inflammatories antihistamines to try to deal with hangover Adam says you can only buy clotem over the counter in Finland but he says that anti-inflammatories like ibuprofen and aspirin might be a good idea.

Speaker 2

There you go. We tried.

But while you're raiding your medicine cabinet, Sangita says to avoid Tylenol. It hurts the liver, which is already hurting enough.

Speaker 6 So, you know, one thing that everyone who's ever been in my lab has learned is don't take Tylenol for a hangover. So if your listeners learn anything else today, that would be a good thing to know.

Speaker 4 This episode was supported in part by the Sloan Foundation for the Public Understanding of Science, Technology, and Economics, as well as the Burroughs Burroughs Welcome Fund for their support of our coverage of biomedical research.

Speaker 2 Thanks to Senghita Batia and Quinton Smith at MIT, Adam Rogers, author of PROOF, Marie Laurence Ack at the University of Picardy, and to all of you who sent us voice memos and left us voicemails with your hangover remedies.

Speaker 2 We of course couldn't use them all, but we loved listening to them.

Speaker 4 Thank you.

Speaker 4 Thanks of course to Superstar Gastropod Fellow Sonia Swanson for her coverage of hangover remedies in Korea and for getting us dried anchovies and teaching us how to take the guts guts out for the soup, as well as putting up with disapproving stares at the Korean grocery store when she bought us the hangover drinks.

Speaker 2 We'll be back in a couple of weeks with my favorite fruit and one of Cynthia's preferred beverages. Like in any long-term relationship, it's important to keep us both happy.