Where Truth Lies

Press play and read along

Transcript

Speaker 1 This is Hidden Brain. I'm Shankar Vedanta.

Speaker 1

In the middle of a workday in April 2013, the Associated Press sent out a tweet. Breaking two explosions in the White House, it read.

Barack Obama is injured.

Speaker 1 The tweet caused panic in the financial markets. Within minutes, the Dow plunged more than 100 points as traders rushed to sell off stocks amid the threat of political instability.

Speaker 1

The news was bogus. There were no explosions and the president was safe.

The AP's Twitter account had been hacked.

Speaker 1 Within a few minutes, the information was corrected and the markets recovered.

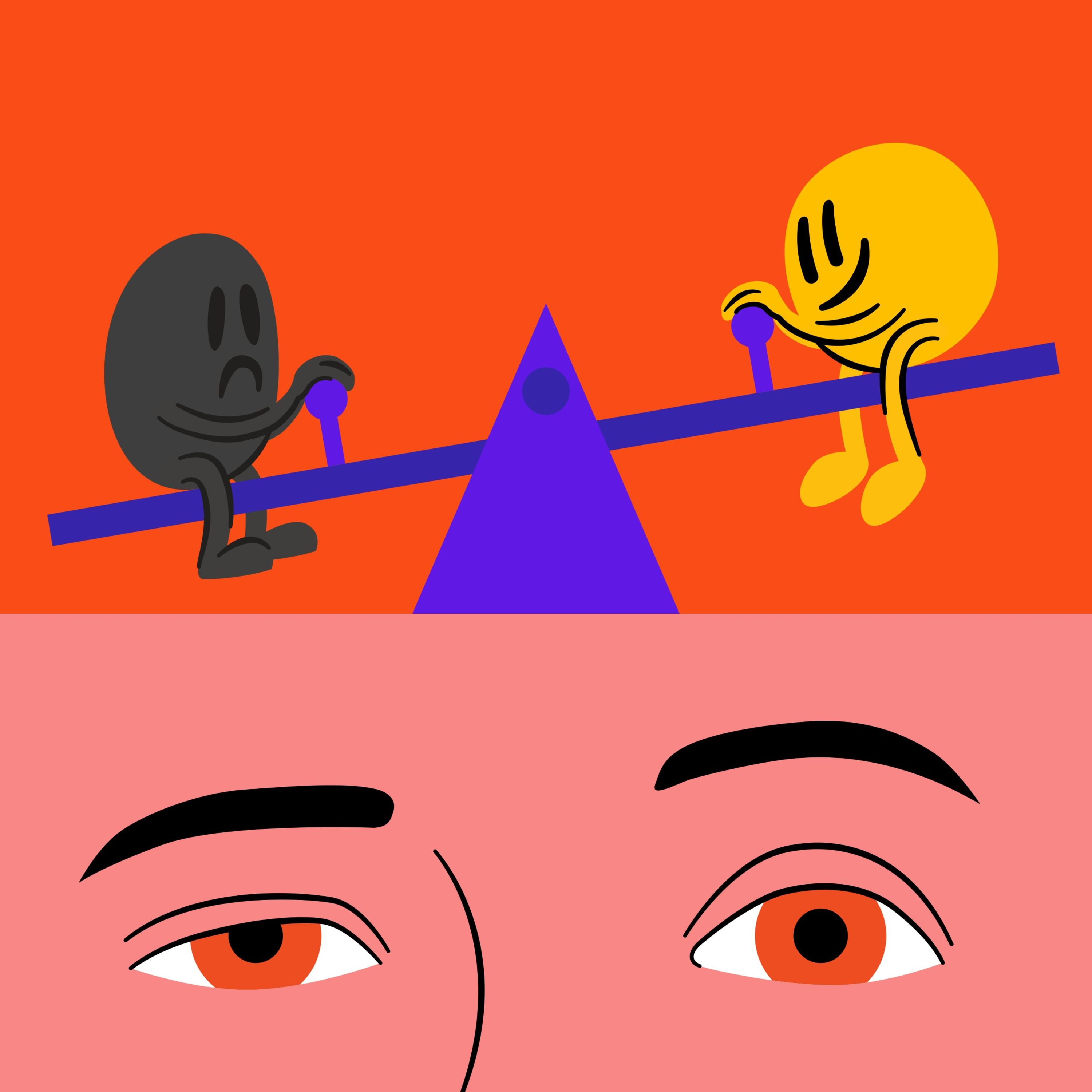

Speaker 1 When we think of misinformation, we often think of stories like this. Blatant cases of lies and falsehood perpetrated by deceitful and malevolent agents.

Speaker 1 But in recent years, social scientists have found that misinformation comes in many flavors, most of which are far subtler than the erroneous AP story.

Speaker 1 These forms of misinformation prey on our mental blind spots and take advantage of our passions and loyalties.

Speaker 1 This week on Hidden Brain: the many insidious forms of misinformation and how we can all get better at separating fact from fiction.

Speaker 1 Support for hidden brain comes from Viz. Struggling to see up close? Make it visible with Viz.

Speaker 1 Viz is a once-daily prescription eye drop to treat blurry near vision for up to 10 hours.

Speaker 1 The most common side effects that may be experienced while using Viz include eye irritation, temporary dim or dark vision, headaches, and eye redness.

Speaker 1 Talk to an eye doctor to learn if Viz is right for you. Learn more at Viz.com.

Speaker 2 You're cut from a different cloth.

Speaker 2 And with Bank of America Private Bank, you have an entire team tailored to your needs with wealth and business strategies built for the biggest ambitions, like yours.

Speaker 2 Whatever your passion, unlock more powerful possibilities at privatebank.bankofamerica.com. What would you like the power to do? Bank of America, official bank of the FIFA World Cup 2026.

Speaker 2 Bank of America Private Bank is a division of Bank of America and a member FDIC and a wholly owned subsidiary of Bank of America Corporation.

Speaker 1

Support for hidden brain comes from ATT. There's nothing better than feeling like someone has your back.

That kind of reliability is rare, but ATT is making it the norm with the ATT guarantee.

Speaker 1

Staying connected matters. Get connectivity you can depend on.

That's the ATT guarantee. AT ⁇ T.

Connecting changes everything. Terms and conditions apply.

Visit att.com slash guarantee for details.

Speaker 1

If you have a computer or a smartphone, you have answers. Want to know what year Abraham Lincoln was born? Look it up.

Curious who invented the wind sock? You can find out in 30 seconds.

Speaker 1

We have access to more information in a minute than our ancestors did in a lifetime. This privilege comes with a problem.

How do we know if what we are seeing is true?

Speaker 1

All of us believe misinformation is something other people fall for. The uncle who gets his information from talk radio.

Your high school classmate who trusts everything he sees on WhatsApp.

Speaker 1

the conspiracy theorist who imbibes lies on YouTube. At the London Business School, economist Alex Edmonds is interested in the science of misinformation.

He says it's not just a fringe problem.

Speaker 1 Misinformation is much more common than we think. Alex Edmonds, welcome to Hidden Brain.

Speaker 3 Thanks, Janka. It's really great to be here.

Speaker 1

Alex, you live in the UK. Some years ago, the British home stores made the news.

BHS, as it's called, is a massive department store chain that sold everything from furniture to clothing.

Speaker 1 What happened in 2016 to get BHS in the news, Alex?

Speaker 3

So it effectively went bankrupt. And when they went bankrupt, they had unfunded pension deficits.

So former employees who were owed pensions did not get them paid.

Speaker 1 So companies go bankrupt all the time, businesses fail all the time, but this became something of a scandal, Alex. Can you explain why?

Speaker 1 What happened here that was not just a business going out of business, but something that felt like malfeasance was at play?

Speaker 3 Certainly, you're absolutely right that just being bankrupt, that is just what business is. That's the nature of the beast.

Speaker 3 But here, what happened was the former owner, Sir Philip Greene, who is a rather larger-than-life character, he took out a lot of money and huge dividends to himself.

Speaker 3 And then he sold this company to a guy called Dominic Chappelle, who was a formerly bankrupt entrepreneur. He'd bankrupt further businesses in the past.

Speaker 3 And so by selling to him, he just put this in jeopardy and didn't care about all of the employees.

Speaker 1

So Alex Philip Greene sells BHS to Dominic Chappelle. Thousands of people lose their jobs.

Many more go without their full pensions.

Speaker 1 News outlets, meanwhile, report that Philip Greene is awaiting delivery of a $150 million super yacht named Lionheart. I'm imagining all this does not endear him to the British public.

Speaker 3 Yeah, that's correct. So again, the fact that a company goes bankrupt, that is part and parcel of business.

Speaker 3 But if the company goes bankrupt and former employees don't have their pensions, and yet there's the person who's got a huge show of extravagance, this is a big problem.

Speaker 1 So around the same time as the BHS scandal, another UK chain Sports Direct faced its own set of controversies. Do you remember what happened, Alex?

Speaker 3 Yeah, so here we had a similar situation with a rather larger-than-life character.

Speaker 3 So, the chairman is a guy called Mike Ashley, who also owned Newcastle United Football Club and therefore was very much in the public eye.

Speaker 3 But Sports Direct was under pressure for a number of reasons, and one of them was not paying the minimum wage. And that was just one of many bad workplace practices.

Speaker 1 So these scandals prompted a parliamentary hearing and you were summoned to testify in front of the Select Committee on Business.

Speaker 1 Now you've been long interested in corporate governance, executive pay, making a case for responsible business practices. Was this why you were called to testify, Alex?

Speaker 3

You're absolutely right, Shankar. This is in my field.

This is in my strike zone. I'm an academic, but I'm really passionate about using academic research for practical purposes.

Speaker 3 So I submitted some written evidence to the inquiry.

Speaker 3 And based on the quality of the evidence submissions, the select committee then calls some witnesses to testify orally in order to delve deeper in the questions that they're trying to address.

Speaker 1 So as you were listening to another witness, you heard something that caught your attention. Tell me what it was, Alex.

Speaker 3 Yeah, so I got in early, perhaps because I was nervous. I needed to swat up on everything I'd written in my testimony just to make sure that if they asked me any questions, that I was prepared.

Speaker 3

But I still listened with one ear open to what was happening. And there was a witness, the Trades Unions Congress.

And what they mentioned was some research which sounded really noteworthy.

Speaker 3 They said, the lower the pay gap between the CEO and the average employee, the better the company performance. And why did my ears prick up when I heard this?

Speaker 3 Because this was something I I really wanted to be true. It shined with my views on responsible business.

Speaker 3 As I just discussed, in many cases, the more responsibly you act towards wider society and your employees, the better the company performance. So this seemed to be music to my ears.

Speaker 1 So you were happy to hear about this research that suggested that the narrower the pay gap between the CEO and the average worker, the better the company did.

Speaker 1 What prompted you then to do the next step of actually looking up the origins of this claim?

Speaker 3

I'd say it was entirely selfish. So I thought this was a great study.

I would like to quote this study.

Speaker 3 So I wasn't coming out to try and check this or to catch anybody out, but I thought, great study, let me know what this study is.

Speaker 3 So the next time that I am to talk to companies about the importance of responsibility, I have another weapon in my arsenal. And so, well, how did I look this up?

Speaker 3

Well, the witness had, like me, submitted some written evidence beforehand. So I went to the written evidence and I found the paper that they cited.

And then I looked up the paper on my iPad.

Speaker 3 And then the paper seemed to say completely the opposite. Actually, the greater the gap between CEO and worker pay, the better the company performance.

Speaker 3 I was confused. I thought maybe because I was so nervous because of my own session, did I misread everything? Perhaps because academic papers are not known for their clarity.

Speaker 3 But no, it was there, as clear as day. The greater the pay gap, the better the company performance.

Speaker 1 What do you think happened? Did they actually just misread the paper?

Speaker 3 So that would be one interpretation is that they just misquoted it, but actually it wasn't as bad as that.

Speaker 3 What I noticed was I was looking at the 2013 version of the paper, but what they quoted in their written evidence was the 2010 version of the paper.

Speaker 3 And when I looked up the 2010 version of the paper, it indeed had the opposite result, the one they originally quoted.

Speaker 3 So what had changed between 2010 and 2013 was the manuscript had gone through peer review, where the peer review process forces the authors to correct any mistakes.

Speaker 3

Once they corrected their mistakes, they found completely the opposite result. Notice that the inquiry was in 2016.

So the 2013 paper was already out there for three years.

Speaker 1

Well, of course, it could have just been an oversight. They happened to come by the 2010 paper.

They didn't realize the 2013 paper was out there. You finished your testimony.

It went well.

Speaker 1 But you decided that you were going to try and correct the record and help the committee basically get the correct paper. And so you went up to them afterwards and told them about the 2013 paper.

Speaker 1 How did you do this? What happened?

Speaker 3 Yeah, so there's a clerk to the select committee who's not a member of parliament, but a senior civil servant.

Speaker 3

And he I was quite cordial with because he was the person I'd interacted with in terms of inviting me to testify. And I mentioned this and he seemed horrified.

He seemed this was really bad.

Speaker 3 Even if it was an honest mistake, he wanted to make sure that this inquiry conducted by the UK government had the best evidence.

Speaker 3 And he invited me to submit a supplement to my initial written evidence, responding to what I'd heard in the earlier session. I did so and the committee published it.

Speaker 1 So that's very promising. Is that how the committee eventually ended up its conclusions? Or does the story go further than this?

Speaker 3 Unfortunately not there is a twist so even though the committee published my supplementary evidence which suggests they endorsed that what I'd written the final report of the inquiry which was made after considering all the written submissions and also the all evidence in the hearings still referred to the overturn result as if it was gospel the idea that lower pay gaps lead to better company performance and this led to them recommending that all companies disclose their pay gaps, and that recommendation eventually did become law.

Speaker 3 So, this was something with some actual consequences.

Speaker 1 And in some ways, I think I can understand how this came about.

Speaker 1 This is coming on the heels of these major scandals where you have these leaders of these companies behaving in ways that are, you know, if not unethical, then clearly perhaps improper.

Speaker 1

Certainly, it didn't pass the seemliness test, if you will. A lot of people lost their jobs, a lot of people had their pension benefits reduced, Politicians got involved.

Parliament got upset.

Speaker 1 And they wanted to hear the story that basically said, you know, you really need to rein in CEO behavior.

Speaker 1 And so in some ways, a study that basically said smaller pay gaps between the CEO and the median worker seemed like it fit that larger thesis.

Speaker 1 Do you think that's how it came about, that that's what the driving impetus was for this error to persist in the final report?

Speaker 3

I do think so. So I don't think the committee set to deliberately misrepresent the evidence.

I think that why did they start the inquiry?

Speaker 3 They did believe that CEOs were overpaid and they think that overpayment is a bad thing, that indeed was potentially a contributor to this two scandals of BHS and Sports Direct.

Speaker 3 Therefore, any evidence that they saw, they interpreted to be supportive of this.

Speaker 3 And if there was evidence against that, they might have dismissed that evidence because it just didn't sound right, it didn't feel right. And so they responded to the evidence selectively.

Speaker 1 When we come back, the the psychological drivers of misinformation.

Speaker 1 You're listening to Hidden Brain. I'm Shankar Vedantam.

Speaker 2 You're cut from a different cloth.

Speaker 2 And with Bank of America Private Bank, you have an entire team tailored to your needs with wealth and business strategies built for the biggest ambitions, like yours whatever your passion unlock more powerful possibilities at privatebank.bankofamerica.com what would you like the power to do bank of america official bank of the fifa world cup 2026 bank of america private bank is a division of bank of america and a member fdsc and a wholly owned subsidiary of bank of america corporation

Speaker 1 support for hidden brain comes from wealthfront it's time your hard-earned money works harder for you.

Speaker 1 With Wealthfront's cash account, earn a 3.5% APY on your uninvested cash from program banks with no minimum balance or account fees.

Speaker 1 Plus, you get free instant withdrawals to eligible accounts every day, so your money is always accessible when you need it. No matter your goals, Wealthfront gives you flexibility and security.

Speaker 1 Right now, open your first cash account with a $500 deposit and get a $50 bonus at wealthfront.com slash brain.

Speaker 1 Bonus terms and conditions apply. Cash account offered by Wealthfront Brokerage LLC, member FINRA, SIPC, not a bank.

Speaker 1 The annual percentage yield on deposits as of November 7th, 2025 is representative, subject to change, and requires no minimum. Funds are swept to program banks where they earn the variable APY.

Speaker 3 This is Hidden Brain.

Speaker 1 I'm Shankar Vedanta.

Speaker 1 There are reams of psychological research on the power of stories. A compelling emotional narrative can capture our attention and persuade us in ways that data and reasoning often cannot.

Speaker 1 But what happens when our feelings are contradicted by the facts? Economist Alex Edmonds has spent years immersed in the world of data, science, and math.

Speaker 1 He's found that there are psychological forces that make misinformation hard to fight.

Speaker 1 Alex, you were once cleaning up your junk email folder when you came across a message that stopped you in your tracks. What was this message?

Speaker 3 So this was a message from one of the leading investors in the world. So I'll call this investor Xin Yi.

Speaker 3 So Xinyi had heard about my research showing that companies with high employee satisfaction beat their peers in terms of total shareholder return over a 28 year period.

Speaker 3 And she was interested in launching a fund based not in employee satisfaction, but gender diversity and wondered if I could do a similar study showing outperformance of more diverse companies.

Speaker 1 So in the earlier work that you had done, Alex, you had examined the 100 best companies in America and looked at sort of what might be driving their success.

Speaker 1 And you found this correlation between employee satisfaction and company success.

Speaker 1 Did you find that employee satisfaction was the driver of company performance or just that the two things were correlated?

Speaker 3 This is really important because as we know, correlation does not imply imply causation, and we need to be particularly careful when there's a danger of confirmation bias.

Speaker 3 We'd love to believe that there's good karma in the world, that companies that treat their workers better do better in the long term. But it could be the opposite.

Speaker 3

It could be that once a company starts doing well, then it can start investing in its employees. Or maybe there's causality in neither direction.

There's a third factor that affects both.

Speaker 3 So maybe a great manager makes her employees happy because she's a great leader, and a great manager makes some good strategic decisions and that leads to better company performance.

Speaker 3 So a lot of the job of an academic is to make sure that we really nail a result.

Speaker 3 In order to get published in a top scientific journal, we need to address those alternative explanations and that's all the blood and sweat and tears that I had to shed in order to get this paper published.

Speaker 1 Alex agreed to meet the famous investor. She invited him to the Dorchester Hotel in Park Lane, London.

Speaker 3

If you play Monopoly, the most expensive square on the Monopoly board is Mayfair. The second most is Park Lane.

So this is really prime real estate.

Speaker 3

And so Park Lane is a road which overlooks Hyde Park, a huge, beautiful park in London. And the Dorchester Hotel was a plush hotel.

I think right now it would cost £800 per night to stay there.

Speaker 3 So the lobby had high ceilings, it had big windows, lots of light was flowing through.

Speaker 3 So it looked to be a beautiful hotel, the sort of hotel that one of the leading investors in the world would be staying at.

Speaker 1 So what did Shenyee want?

Speaker 3 So she mentioned that she was potentially going to be launching this new fund based on gender diversity. And she heard of my prior study.

Speaker 3 So she first asked whether I could directly tell her whether that study already showed that diversity led to outperformance.

Speaker 3 And I said, no, because employee satisfaction covers many things, not just diversity, but things like fair pay, credibility, respect, fairness, pride and camaraderie.

Speaker 3 So she said, well, could I not adapt my methodology and rather than looking at employee satisfaction, look at diversity as being the driver? And I said, yeah, potentially.

Speaker 3 And indeed, there's a lot of measures out there of diversity that we could look at. It could be diversity in the boardroom, diversity in the workforce.

Speaker 3 It could be winning a working mother or similar award. It could be the number of gender controversies in the news.

Speaker 1 And so, you decided to take on this study. What did you think was exciting about the idea? What did you think that you would get out of it?

Speaker 3 It was the potential to partner with her in the launch of this fund. So, clearly, it was a preliminary discussion.

Speaker 3 We didn't discuss any terms or anything, but the reason for the meeting was implicitly that I could help her launch the fund. And this would have been amazing for my career.

Speaker 3 So, not only might this be good financially, but I would be catapulted into the mainstream from the academic backwaters in which I was used to working in.

Speaker 3 And also it's something I cared about intrinsically. So as an ethnic minority, I believe diversity to be very important.

Speaker 3 And if indeed you could launch a fund which does well for society in terms of promotion of females, If this led to higher financial returns, that would be a win-win.

Speaker 3 And that would be good for me intrinsically in addition to the instrumental benefits of financial returns and also perhaps greater recognition.

Speaker 1 So what did you do? Did you launch such a study, Alex?

Speaker 3 I did. I did do that study and there were 24 different measures of female friendliness available.

Speaker 3 And so I worked with one of my MBA students at Wharton who was somebody who was a stellar student, who got an A-plus in my class. He had also told me that he was really interested in ethical business.

Speaker 3 So we worked together. correlating these 24 different measures of performance with long-term financial returns.

Speaker 1 And what did you find?

Speaker 3 So unfortunately, we did not find what we hoped to find. So, the vast majority of these measures found a negative relationship with long-term shareholder returns.

Speaker 3 There were only two measures which found a positive relationship. One of them was insignificant.

Speaker 3 So, what that means is that the increase in returns was so small that it could have been due to luck rather than gender equality.

Speaker 3 But there was one result where there was a significant relationship between female friendliness and long-term shelter returns.

Speaker 1 So what did you do? What did you go back and tell the investor who had asked for the study? What did you report?

Speaker 3 Well, what we should have done was just report the two ones that were successful.

Speaker 3

And that would have been great because then I might have partnered with her in the launch of this fund. But that would not be correct.

So my job is a researcher.

Speaker 3 And as a researcher, you can't just bury some results because they don't support what you'd like to find.

Speaker 3 So we reported all of the results, including the huge number, which unfortunately found no relationship or a negative relationship. And we sent this to Xin Yi.

Speaker 1 Did Xinyi accept the results? What was her reaction?

Speaker 3 She seemed disappointed, but she seemed to accept that this is just what the results were. She thanked me, and then that was the end of the project.

Speaker 1 Was this the end of the story, though?

Speaker 3 It unfortunately was not.

Speaker 3 So a few months later, I saw a press release where Xin Yu was launching a new fund based on gender diversity and this was the very thesis that she'd asked me to study and this was surprising because in the press release announcement it said that there was a strong relationship between gender diversity and long-term financial performance which was the very thesis that I had found not to be true.

Speaker 3 So my results overall did not support it. But what she did find was some study done done by a commercial company, which suggested there was a positive link between gender and financial performance.

Speaker 1 You call this idea data mining, and you say that both researchers as well as advocacy organizations are sometimes guilty of this. Can you explain what data mining is?

Speaker 3 Yeah, so data mining is that you start with a preferred result that you want to find, and then you mine the data. You run the data in so many different ways until you get a positive result.

Speaker 3 So here there were so many measures of performance that you could have tried, also so many ways that you could have measured diversity.

Speaker 3

And what she was able to find was a company which had delivered a positive result. Now here, the data mining was not done by Xing Yi.

It was done by the company.

Speaker 3 But why might the company have wanted to get a positive result? Because the idea that diverse companies perform better, that's something that that people want to be true.

Speaker 3 If indeed you deliver the result, you might be picked up. And indeed, their paper was picked up indeed by Xinyi and that led to positive publicity for that organization.

Speaker 1 Now, I just want to clarify, Alex, that you're not saying that you think CEOs should get exorbitant payouts in excess of their workers or that diversity is a bad thing.

Speaker 1 You're just saying we need to trust the evidence as it comes in and report it accurately.

Speaker 3

Absolutely. And this is irrespective of of your personal views on the topic.

So, personally, I believe that diversity is important. It's an important thing.

Speaker 3 As an ethnic minority, it's something which is dear to me. But I believe that as a scientist, you should be like an expert witness in a criminal trial.

Speaker 3 Your role as a scientist is to state the evidence, just like your role as a witness is to state the evidence clearly, irrespective of your views of the issue.

Speaker 1 I want to talk about another driver of misinformation. Tell me the story of a woman named Belle Gibson.

Speaker 3

Belle Gibson was a young Australian. She had cancer and this cancer was terminal.

She had tried radiotherapy and chemotherapy and none of that worked. So instead, she tried clean eating.

Speaker 3

And she was blogging about her journey and she made a miraculous recovery. She was cured from her cancer.

And this story went viral. It was shared.

It could have reached millions.

Speaker 3 And it couraged other people to shun traditional medicine, chemotherapy and radiotherapy for diet and exercise. She got a book deal.

Speaker 3 And this book deal was with Penguin Australia to have a cookbook showing what she did in order to cure herself from cancer.

Speaker 3 She also launched a healthy eating app called The Whole Pantry with recipes which were apparently curative of some of the most serious diseases.

Speaker 1 I mean, this is a fairy tale story Alex. So someone has cancer, they cure themselves of cancer, they become a best-selling author, a successful entrepreneur.

Speaker 1 An amazing story Alex, is there any problem with it?

Speaker 3 Yes, there was one problem and sadly a big problem. She never had cancer.

Speaker 3 So this was a lie. People shared a story without ever checking whether it was true.

Speaker 1 Some of the story is also about us, isn't it, Alex? Which is that we wanted to believe that story. That story was appealing to us.

Speaker 1 Part of the reason she became a successful author and entrepreneur is because the story she was telling was a story that we actually wanted to hear.

Speaker 3

Absolutely. This was another example of confirmation bias.

So why did we want to believe Belle's story? Because what it suggested is that you can achieve anything you want to.

Speaker 3

You can defeat even cancer if you just put your mind to it. And this is what we tell our kids.

We tell them, you can do anything you put your mind to.

Speaker 3 And so the idea that she was shunning traditional medicine, these were the chemicals that you get injected with if you're doing chemotherapy for something like clean eating.

Speaker 3

And that again accords with our worldview that something natural is better than the medicines of a giant corporation. So it sort of made sense to us.

And she was inspiring.

Speaker 3 And so she inspired everybody that even if you were at death store, you could have a second chance of life. We love those underdog stories.

Speaker 3 They are in the fairy tales we learn as kids, we read as kids, but this was apparently not a fairy tale. This was somebody who we could see, looked really well, and was eating healthily.

Speaker 1 So you say that the Bella Gibson story is an example of something called the narrative fallacy. What is the narrative fallacy here, Alex?

Speaker 3 The narrative fallacy is to see some events and believe that there is a link between the two, is that we can weave in a narrative which supports our view of the world.

Speaker 3 So if we see claim that she had cancer, now claim that she didn't have cancer anymore, was cured, and we can see that she was clean eating, we weave in the explanation that we want, which is the clean eating cured her cancer.

Speaker 3 Now, there's alternative explanations to this, and an alternative explanation could be that she lied. because nobody had ever checked her claim of cancer.

Speaker 3 Or even if she was cured, it could have been that she did other things to have been cured. Or maybe she didn't lie, but she was misdiagnosed in the first place.

Speaker 3 But those narratives don't feel so good to us. So we latch onto the one narrative that we like.

Speaker 3 Just going back to the criminal trial example, it would be like the police latching onto one particular suspect because of some particular prejudice and ignoring the alternative suspects.

Speaker 1 You know, we've talked elsewhere on the show about how the brain is a sense-making machine, and we are in some ways evolutionarily wired to draw connections and see patterns and seek out explanations.

Speaker 1 So we may have all of the world's information at our fingertips, but in some ways we still have the same brain to make sense of it all.

Speaker 3 So Daniel Kahneman, in his book, Thinking Fast and Slow, said there are two systems. There's the system two, which is rational.

Speaker 3 It knows to check the facts before ditching chemotherapy, check that this person actually did have cancer and was cured from clean eating.

Speaker 3 But there's the system one, which is the part of the brain that is activated by a fight or flight response.

Speaker 3 And that is one where we believe what we want to be true and we're not acting in a discerning way.

Speaker 3 So even really smart people who most of the time can activate their system two, and this is a really well-functioning system, when indeed our emotions take over, we forget basic things like correlation is not causation, check the facts, or are there other narratives than the one that we're trying to ascribe?

Speaker 1 So, we talked earlier about how, you know, the evidence can sometimes be unreliable because researchers and policymakers can pick and choose their findings.

Speaker 1 But even when the data holds up, we sometimes can use data to make claims that are not necessarily supported by the data. You have a story about this.

Speaker 1 Tell me about the day that your son Casper was born and everything you had learned about raising a newborn child.

Speaker 3 Yeah, so this was an amazing day, as anybody who's experienced the birth of a child will know. And so we had huge positive emotions, but then we realized we need to look after this little guy.

Speaker 3 And one of the big questions is what to feed him. And my wife and I thought, well, this is a no-brainer.

Speaker 3 We had taken a National Childbirth Trust parenting course, and the NCT is extremely well respected within the UK.

Speaker 3 And they talked about many things such as changing mappies, what to do if the baby is sick, but there were two classes devoted to breastfeeding.

Speaker 3 And while much of this was on how to breastfeed, it started with why breastfeed.

Speaker 3 The idea being that breastfeeding is tough, so if they convinced us of the benefits, then even if we were bleary-eyed and weary and wanted to reach for the bottle, we wouldn't because of the benefits.

Speaker 3 And so what they gave was a message which was also reinforced by the World Health Organization, which said that you should exclusively breastfeed at least for the first six months.

Speaker 3

No water, no formula, no other fluids. And so why did they give this advice? Because of a strong correlation based on data.

And what was that correlation?

Speaker 3 Babies who were breastfed exclusively had better outcomes later in life. This could be mental outcomes such as child IQ.

Speaker 3 That could be physical outcomes as well, such as reduction in allergies and other potential ailments.

Speaker 1 So in some ways,

Speaker 1 the data linking breastfeeding with good outcomes in life is really voluminous. I mean, there are probably warehouses of studies now that show the connection between these two things.

Speaker 1 But in the early days of your son's life,

Speaker 1 your doctors recommended feeding your child newborn formula along with breast milk. What was the reasoning here?

Speaker 3 Yeah, so the obstetrician said that in Casper's case, because he was born a little bit underweight, that it was important to top him up with formula.

Speaker 3 And also, because he was born a little bit early, there was the risk of jaundice. So, what is this?

Speaker 3 This is when there's lots of bilirubin in the system, and bilirubin is something which, if it accumulates, can cause jaundice. And in babies born early, this is particularly prevalent.

Speaker 3 And so, the advantage of putting formula in is that that would flush out the bilirubin and reduce the risk of jaundice.

Speaker 3 So, to us, it was not as black and white as the World Health Organization or the NCT course was suggesting.

Speaker 1 So what did you do? On the one hand you have these warehouses of data telling you that breastfeeding is the only way to go and your doctor is basically saying you know breastfeeding and formula.

Speaker 1 What did you do?

Speaker 3 So I did my own research and I thought this is my job as an academic. If I do this in my day job, shouldn't I also do this research in something as important as my child's well-being?

Speaker 3 So I did some Google searches myself.

Speaker 3 So I didn't didn't just take at face value the studies quoted by the NCT, because as you're mentioning, if you have a particular viewpoint, you can find the studies to support that viewpoint.

Speaker 3 But if I googled breastfeeding IQ, I found lots of studies which also reinforced the result that the NCT course had suggested.

Speaker 3 But then when I clicked on those particular studies, it actually gave a more nuanced picture.

Speaker 3 So what they found is that if you did a simple comparison of breastfed versus bottle-fed kids, then there was a difference in IQ and other outcomes.

Speaker 3 But what some studies also did was they realized that you needed to make adjustments. Why?

Speaker 3

Because breastfed and bottle-fed babies differ according to many other dimensions, not just the feeding method. So breastfeeding is really tough.

it can be difficult without family support.

Speaker 3 So maybe it was babies with a better home life, a superior home environment that were breastfed. And it could be that home environment led to the better outcomes, not the feeding methodology.

Speaker 3

Also, older mothers tended to breastfeed. It could be the mothers more educated.

There were other things such as the mother who was less likely to smoke is also more likely to breastfeed.

Speaker 3 And it could be all of those factors which were behind the child outcomes, not the feeding method.

Speaker 3 And in fact, when these studies controlled for those other factors, what that means is when they stripped out the the influence of those other factors on IQ and the other outcomes, the link between breastfeeding and IQ was pretty much zero.

Speaker 1 So again, I don't think what I'm hearing you saying is that breastfeeding is ineffective or useless.

Speaker 1 You're basically saying that black and white thinking about breastfeeding might be the problem here.

Speaker 3 That is correct. And so why is this such an important issue is that many women feel guilt-tripped into only breastfeeding and they feel guilty if they are considering something else.

Speaker 3 And this is problematic because it means that if they're exhausted, then they are still trying to breastfeed, and that exhaustion can actually be bad not just for the mother, but also for the child's development.

Speaker 3 It also means that as a father, you can't get as involved in feeding, and feeding is one way to bond with your child.

Speaker 3 And so, the message which is often perpetrated, which is never do anything other than breastfeeding, is where a careful look at the data is really important. important.

Speaker 1 The world makes it easy for us to find facts that confirm our pre-existing beliefs and seek out stories that tell us our values and our hearts are in the right place.

Speaker 1 So how can we know whether to trust what we read, watch and hear?

Speaker 1 When we come back, strategies for sifting through the information coming at us every day and fighting back against falsehoods and bad actors.

Speaker 1 You're listening to Hidden Brain. I'm Shankar Vedanta.

Speaker 1 Support for Hidden Brain comes from Whole Foods Market.

Speaker 1 With great prices on turkey, sales on baking essentials, and everyday low prices from 365 brand, Whole Foods Market is the place to get everything you need for Thanksgiving.

Speaker 1 Fresh whole turkeys start at $2.99 a pound. Explore sales on select baking essentials from 365 brand like spices, broths, flour, and more.

Speaker 1 Shop everything you need for Thanksgiving now at Whole Foods Market.

Speaker 1 Support for Hidden Brain comes from Masterclass. Looking to grow, learn, or simply get inspired? With Masterclass, anyone can learn from the best to become their best.

Speaker 1 For as low as $10 a month, get unlimited access to over 200 classes taught by world-class business leaders, writers, chefs, and more. Each lesson fits easily into your schedule.

Speaker 1 Watch anytime on your phone, laptop or TV or switch to audio mode to learn on the go. 88% of members say Masterclass has made a positive difference in their lives.

Speaker 1 Masterclass, where the world's best, teach you how to be your best. Masterclass always has great offers during the holidays, sometimes up to as much as 50% off.

Speaker 1

Head over to masterclass.com slash brain for the current offer. That's up to 50% off at masterclass.com slash brain.

Masterclass.com slash brain.

Speaker 3 This is Hidden Brain.

Speaker 1 I'm Shankar Vedanta.

Speaker 1 When we think of misinformation, we think of politicians making outlandish claims or self-proclaimed experts selling snake oil.

Speaker 1 But in reality, misinformation isn't always obvious and not easily avoidable.

Speaker 1 Much of the time, the things we fall for are shaped by our own psychological needs and biases.

Speaker 1 Economist Alex Edmonds is the author of the book, May Contain Lies, How Stories, Statistics, and Studies Exploit our biases, and what we can do about it.

Speaker 1 Alex has a powerful example of misinformation in his own life. He once watched an inspiring talk given by an acrobat with the entertainment company Cirque de Soleil.

Speaker 3 So, what this talk was about was the idea of the 10,000 hours rule. So, people wondered how this guy James was so able to perform amazing acrobatics.

Speaker 3 And he said this was not due to any hidden gene or special innate talent, but just hours and hours of deliberate practice.

Speaker 1 So what the acrobat was following is what's known as the 10,000 hours rule, which was popularized by the famous author Malcolm Gladwell in his book Outliers.

Speaker 1 The idea was you could be successful in a number of domains if you put in 10,000 hours of deliberate effort. Why was this idea appealing to you, Alex?

Speaker 3 Because this confirmed everything I thought to be true. So you're told when you're young, practice makes perfect, you can do anything you put your mind to, and also it's empowering.

Speaker 3

This suggests that you're not a slave to genetics. If you want anything in life, you can get it as long as you're willing to put in the effort.

And it also accords with our views of good work ethic.

Speaker 3 We'd like to believe that the people who succeed are not just given some magic powers, but they really had to work in order to get where they were.

Speaker 1 Now, besides being an economist, I understand you're also an avid tennis player and you tried to imbibe the 10,000 hour rule in improving your tennis game. Tell me what you did.

Speaker 3 Yeah, so I used to love to play tennis and still do. And so, I played quite a lot of tennis during my time at MIT when I was a PhD student with a couple of friends.

Speaker 3

And one guy called Florian Ederer, he always wanted to play a game against me. He always wanted to keep score.

But to me, I already had enough stress doing my PhD.

Speaker 3

I didn't want to add extra stress with this game. And also, Florian Ederer is F.

Ederer, so I was intimidated by keeping a score against somebody whose name was effectively Federer.

Speaker 3 But what the 10,000 hours rule suggested is all that mattered was the hours that you put in.

Speaker 3

So it didn't matter whether you're playing a game or knocking the ball around. So I thought, let me just knock the ball around because that is just fun.

And I'm getting my hours in.

Speaker 3 I'm moving myself towards the magic number.

Speaker 1 Alex didn't just follow the 10,000 hours rule, he preached it to others.

Speaker 3 So, I had actually used this 10,000 hours rule in my class when I was an assistant professor at Wharton. I typically gave as my final lecture some advice about general life,

Speaker 3 similar to a last lecture that you sometimes see professors give. And the 10,000 hours rule was often featured.

Speaker 3 And when I talked about this, I get knowing nods as if this was a truth universally acknowledged.

Speaker 1 A few years later, Alex moved to London. He began a part-time position at another college where he planned a lecture on the growth mindset.

Speaker 1 This is the idea that you can achieve much more when you don't believe your abilities are limited. With hard work and dedication, you can accomplish more than you ever thought possible.

Speaker 1 The 10,000 hours rule was to take center stage in the lecture, so Alex figured he should go back and read the original claim carefully. He found a couple of things that worried him.

Speaker 3 So the first was I had actually learned an incorrect version of the rule. So Malcolm Gladwell had never claimed that 10,000 hours leads to success.

Speaker 3

That would suggest that 10,000 hours was sufficient for success. Instead, he claimed that 10,000 hours was necessary for success.

What is the difference?

Speaker 3 So Gladwell suggests you might need talent, but talent alone is not going to get you there. You need talent plus hard work.

Speaker 3 But the second issue is Gladwell is far from blameless either, because even his version of the rule was not backed up by underlying data.

Speaker 3 So the main paper that he cites in support of his rule, he calls it exhibit A in the book, is a paper by Anders Erickson, a psychologist, which looks at violinists. So that should already ring a bell.

Speaker 3 right violinists is one specific activity and yet this rule apparently applied to becoming an acrobat being a chess player, being a neurosurgeon, but those are all quite different contexts.

Speaker 3 But let's take that aside. What did this violin study look at? It looked at violin students at the Berlin Academy of Music.

Speaker 3 It had the teachers classify them according to whether they thought they were good or not. So number one, this never actually measured success.

Speaker 3

So Malcolm Glanwell's book is about the story of success. Here, this was just teachers' perceptions of whether they would be good.

And so that again suggests there could be alternative theories.

Speaker 3 If indeed you know that the student is practicing a lot, you're much more likely to say that they are successful, right?

Speaker 3 Because your violin ability is not something easily measurable like a half marathon time. So if you know somebody's working hard, you probably think they're doing better.

Speaker 1

And there were more problems with the study. It asked students how many hours they had practiced from age five onwards.

Some of the students were in their 20s at the time of the study.

Speaker 3 Another issue is that how would you know how long you practiced? Could you remember 18 years ago when you were age five, how much you practiced back then? You probably couldn't.

Speaker 3 And again, this could be skewing things. Why? Because if you know you're doing really well right now, you're a great violinist, you think I must have practiced.

Speaker 3 And if you're not doing so well, then you think, well, I can't have practiced that hard.

Speaker 3 How you're doing right now affects your reports of your practice rather than the practice affecting whether you're successful.

Speaker 3 And finally, and this is particularly pertinent for me, the study bit Eric said never said it's just about the quantity of hours. He also highlighted the quality.

Speaker 3 So what matters is perhaps deliberate practice guided by a coach, which is difficult and uncomfortable, not just jam sessions.

Speaker 3 And my hitting around with Florian Edere without keeping score, that was the equivalent of just jamming around.

Speaker 3 around, whereas keeping score and playing a game, that was what was going to get me better.

Speaker 1 You know, Alex, I think one thing this story tells me is that there are ideas and concepts that get into

Speaker 1 the stream of public life. And once they are there, they take on a life of their own.

Speaker 1 So even if Anders Erickson and Malcolm Gladwell come along to say, you know, that is not really what I said, that is not really what I meant, the sheer inertia of the collective belief now becomes almost impossible to stop.

Speaker 3 So I think there's a phrase that the lies are spread halfway around the world before the truth has put the shoes on, and this is what we see in terms of misinformation.

Speaker 1 Let's talk about some ways in which we can combat these problems. You recommend a few exercises that can help all of us, and one of them is called consider the opposite.

Speaker 1 What is the consider the opposite exercise, Alex?

Speaker 3 So the consider the opposite idea is to try to get around this problem of confirmation bias. So again, what is confirmation bias?

Speaker 3 We latch on to something uncritically if it confirms what we want to be true, and we reject something out of hand if we don't want it to be true. So why is this interesting?

Speaker 3 Because what it means is that we are able to show discernment. If there's a study that we don't like, we can come up with a whole host of reasons for why it's unreliable.

Speaker 3 And so what I'm doing with the consider the opposite rule is to try to activate the discernment that we already have and we use selectively for studies that we don't like, but now apply it to studies that we do like.

Speaker 3 So maybe just by giving an example, this will come to life. So let's say I want an excuse after finishing this podcast to drink loads of red wine.

Speaker 3 So I might look up on Google why red wine is good for your health and I find studies that people who drink red wine live longer.

Speaker 3 But consider the opposite. We'll ask, what if I found the opposite result? People who drink red wine live shorter.

Speaker 3

How would I try to attack that result? I might say, well, maybe people who drink red wine are poor. They can't afford champagne.

They have to drink red wine instead.

Speaker 3 And it's that poverty which leads to a shorter life, not the red wine.

Speaker 3 But now I've alerted myself to the alternative explanation of income being the driver, then I should ask, is this the driver of the result that I do want?

Speaker 3 Again, red wine is correlated with longer life. Is it the case that the people who can afford red wine are richer and it's their wealth that leads to the longer life?

Speaker 3 So the idea of considering the opposite is to trigger the discernment that we exercise selectively and make sure it's now universal.

Speaker 1 One of the other techniques that you recommend that can help us combat misinformation and confirmation bias is curiosity. And perhaps that's not a technique as much as an orientation.

Speaker 1 But talk about how curiosity can be a defense against our own biases.

Speaker 3 Yeah, so this is also interesting because often we think that just general knowledge is perhaps a way to avoid misinformation because the smarter we are, the more able we are to separate the wheat from the chaff.

Speaker 3 But unfortunately, this is not the case. There are some studies which actually suggest that

Speaker 3 knowledge makes things worse because the more sophisticated we are and the more intelligent we are, the easier it is for us to slam evidence we don't like and to come up with reasons for why we don't want to believe it.

Speaker 3

But we again we deploy this only selectively. We don't deploy this to the evidence that we do like.

So even if knowledge doesn't work, well, actually curiosity does.

Speaker 3 So there was a study which looked at the effect of knowledge, found it had no effect, but curiosity did have an effect.

Speaker 3 So these researchers found that the more curious you were, the more balanced you were on issues such as climate change.

Speaker 3 In particular, your views on climate change were less linked to your political affiliation. So you were going based on the evidence, not based on your identity.

Speaker 1 You also recommend that people ask themselves questions, questions like, do I want this conclusion to be true? Or is this conclusion extreme? Or does this conclusion imply universality?

Speaker 1 And I guess all these questions are ways of basically asking people to slow down the freight train of their conclusions to basically say, is there an alternative explanation that I'm not seeing?

Speaker 3 Absolutely.

Speaker 3 Again, it's just to exercise discernment, which we already do sometimes and selectively, but let's try to do this all the time, including and in particular for things that we do want to be true.

Speaker 1 You know, one thing that strikes me here, Alex, is that we often feel that misinformation is the province of our enemies enemies and our opponents.

Speaker 1 So we all find it easy to see our opponents as being misled by false information, our political opponents in particular. We imagine that they are the source of false information.

Speaker 1 But one pattern in our conversation that I'm gleaning is that one of the greatest sources of our vulnerability is, in fact, not our enemies, but our friends.

Speaker 1 We're skeptical when our enemies and opponents talk. We want to believe our friends.

Speaker 3 We do, and we also want to believe ourselves. So, an even greater enemy than our friends is perhaps ourselves, because it means that we are latching onto particular types of information.

Speaker 3 And while you might think, well, this is a depressing conclusion, is that our friends and ourselves are the cause, it's actually an uplifting conclusion because it means that the solutions are within ourselves.

Speaker 3 Because if the source of misinformation was the enemy, they're going to keep producing misinformation, we can't do anything about it.

Speaker 3 But if indeed the problem is the way that we respond to information is based on our biases, we latch onto what we want to be true, we ignore what we don't, just by changing this using strategies such as consider the opposite that will allow us to be able to combat the misinformation that we see.

Speaker 1 Alex Edmonds is the author of the book, May Contain Lies, How Stories, Statistics, and Studies Exploit Our Biases and What We Can Do About It.

Speaker 1 Alex, thank you so much for joining me today on Hidden Brain.

Speaker 3 Thanks Shankar, really enjoyed the conversation.

Speaker 1 Hidden Brain is produced by Hidden Brain Media. Our audio production team includes Annie Murphy-Paul, Kristen Wong, Laura Correll, Ryan Katz, Autumn Barnes, Andrew Chadwick and Nick Woodbury.

Speaker 1 Tara Boyle is our executive producer. I'm Hidden Brain's executive editor.

Speaker 1

We end today with a story from our sister show, My Unsung Hero. This My Unsung Hero segment is brought to you by Discover.

Our story comes from Angela Zhao in Beijing.

Speaker 1 In 2020, when Angela was just 10 years old, she entered her first piano competition. She was excited, but right before it was her turn to perform, she started to doubt herself.

Speaker 4 What if I played the wrong note? What if I forgot the notes?

Speaker 4 What if I just messed up?

Speaker 4 Then a competitor of mine made me confident. She was the person before me to perform on the stage.

Speaker 4 Before it was my turn to go on to the stage and perform my piece, she looked at me and smiled with thumb up. Her smile made the stage light lighter and warmer to me.

Speaker 4 She made me stop thinking too much and started to think that I can do that.

Speaker 4 Her smile made me think that the stage is just right for me and the piano is just right for me. Most importantly, that smile made me think that today

Speaker 4 I'm just right

Speaker 4 and I can perform on the stage.

Speaker 4 After my performance, I can see that she clapped for me and looked straight at me.

Speaker 4 As a competitor, she gave me me respect and helped the shy girl to face the state.

Speaker 4 That girl from that day, if you can hear this, I just want you to know, you changed the moment of my life and your kind smile remained in my memory. And I'll take that smile as a precious gift.

Speaker 1 Angela Zhao lives in Beijing, China. The piano you're hearing right now is Angela's performance in that very competition for which she won the Silver Award.

Speaker 1 This segment of My Unsung Hero was brought to you by Discover. Discover believes everyone deserves to feel special and celebrates those who exhibit this spirit in their communities.

Speaker 1 I'm a long-standing card member myself. Learn more at discover.com/slash credit card.

Speaker 1 For more of our work, please consider joining our podcast subscription. Hidden Brain Plus is where you'll find exclusive interviews and deeper dives into the ideas we explore on the show.

Speaker 1

You can try Hidden Brain Plus with a free seven-day trial at apple.co slash hidden brain. If you're an Android user, you can sign up at support.hiddenbrain.org.

Those sites again are

Speaker 1 slash hiddenbrain and support.hiddenbrain.org.

Speaker 1 I'm Shankar Vedantam. See you soon.

Speaker 5 What can 160 years of experience teach you about the future?

Speaker 5 When it comes to protecting what matters, Pacific Life provides life insurance, retirement income, and employee benefits for people and businesses building a more confident tomorrow.

Speaker 5 Strategies rooted in strength and backed by experience. Ask a financial professional how Pacific Life can help you today.

Speaker 5 Pacific Life Insurance Company, Omaha, Nebraska, and in New York, Pacific Life and Annuity, Phoenix, Arizona.