How Our Brains Learn

Press play and read along

Transcript

Speaker 1 is Hidden Brain. I'm Shankar Vedanta.

Speaker 1 There's a scene in the 1986 movie Ferris Bueller's Day Off that has become iconic. It's a spot-on portrayal of what it feels like to be disengaged and disaffected.

Speaker 1 In the film, actor Ben Stein plays an economics teacher who is not about to win any teaching awards. He speaks in a deathly monotone.

Speaker 2 In 1930, the Republican-controlled House of Representatives, in an effort to alleviate the effects of the anyone, anyone, the Great Depression,

Speaker 2 passed the anyone, anyone, a tariff bill.

Speaker 1 The students in the classroom are suffering from a boredom that verges on the catatonic. On and on the teacher goes, asking for responses, but barely expecting any.

Speaker 1 And indeed,

Speaker 1 no one ventures a word.

Speaker 2 Today we have a similar debate over this. Anyone know what this is, class? Anyone?

Speaker 2 Anyone? Anyone seen this before?

Speaker 3 The laugher curve.

Speaker 2 Anyone know what this says?

Speaker 1

It says... There is no spark of interest or curiosity.

The moviegoer can hardly blame Ferris for skipping out on school to spend a day of fun with his friends.

Speaker 1

For many of us, there is a reason this scene may be resonant. Our own time in school might have resembled this.

Students currently enrolled may experience a shiver of recognition.

Speaker 1 It's not just in educational settings. Have you ever attended a meeting where leaders of your organization drone on about some new initiative or corporate mumbo-jumbo?

Speaker 1 As your eyelids grow heavy with sleep, you fear your head is going to fall through your interlaced fingers and crash onto the conference table.

Speaker 1 What is missing from these classrooms and conference rooms is engagement, a state of being absorbed and alert where you are eager to learn and know more.

Speaker 1 This week on Hidden Brain, why so many of us feel apathetic at school and at work,

Speaker 1 and how to cultivate the magic of engagement.

Speaker 1 Support for Hidden Brain comes from Viz.

Speaker 1 Struggling to see up close, make it visible with Viz.

Speaker 1 Viz is a once-daily prescription eye drop to treat blurry near vision for up to 10 hours.

Speaker 1 The most common side effects that may be experienced while using Viz include eye irritation, temporary dim or dark vision, headaches and eye redness.

Speaker 1 Talk to an eye doctor to learn if Viz is right for you. Learn more at viz.com

Speaker 1 Support for hidden brain comes from WaterAid, changing the world through water. Imagine walking miles every every day to collect water because your home has no taps, no toilets, no clean water.

Speaker 1 That's the reality for one in four people worldwide. Your support can help change everything for them because everything starts with water.

Speaker 1 Donate to WaterAid and your gift will be matched going twice as far. Donate at wateraid.org slash podcast

Speaker 1

Support for hidden brain comes from AT ⁇ T. There's nothing better than feeling like someone has your back.

That kind of reliability is rare, but ATT is making it the norm with the ATT guarantee.

Speaker 1

Staying connected matters. Get connectivity you can depend on.

That's the ATT guarantee. AT ⁇ T.

Connecting changes everything. Terms and conditions apply.

Visit ATT.com slash guarantee for details.

Speaker 1 I remember many days during my school years when I was so bored I would fall asleep in class.

Speaker 1 But on those very same days, I would find myself alone in a university library at night, poring over books that had nothing to do with my classwork, oblivious as the hours slipped by.

Speaker 1 How could the same person be bored to death in one academic setting and completely engaged in another?

Speaker 1 At the University of Southern California, psychologist and neuroscientist Mary Helen Imordino-Yang has explored this question for many years. She studies the science of engagement and motivation.

Speaker 1 Mary Helen Imordino-Yang, welcome to Hidden Brain.

Speaker 3 Thank you for having me.

Speaker 1 Mary Helen, you're now a professor of education, but as a kid, I understand that you struggled to feel engaged by school.

Speaker 3

I really did. I couldn't understand kind of what the point was or what it meant to do things there.

And school really didn't feel like it was about learning for me.

Speaker 3 It felt like it was about doing stuff.

Speaker 3 And I can hardly describe the sense of just release on Friday afternoon and the dread on Sunday night

Speaker 3 through my late elementary, especially and early middle school, sixth grade year. I finally ended up for a lot of complex reasons for things that were happening at school.

Speaker 3 I finally ended up just kind of stopping going to school. I sort of was like a soft dropout about, you know, I just stopped getting up in the morning.

Speaker 3 And I think my parents just kind of stood back and realized I was doing all kinds of interesting things.

Speaker 3 We had the great fortune of living in the woods in Connecticut in a very remote place.

Speaker 3 And my parents were both from the inner city, one from Detroit, one from Yonkers, New York, right?

Speaker 3 They decided they were going to raise their kids on a farm and try to grow what we ate and, you know, have animals and all kinds of things.

Speaker 3

And so I was really deeply involved with running that farm, taking care of the animals. I was playing the piano.

I was,

Speaker 3 you know, running around in the woods, training dogs and, you know, all kinds of things that was keeping me very, very busy.

Speaker 1 I understand that at one point your grandmother once discovered something unusual in her refrigerator that you had left there.

Speaker 1 Tell me that story, Mary Helen.

Speaker 3

Oh, God, I was a little older. And that actually represents a turning point in my education, I think.

My parents

Speaker 3 had the resources to be able to find a different kind of education system for me. So they moved me the following year into

Speaker 3 a private school that had,

Speaker 3 as it turns out, much more rigorous and interesting academics in addition to all kinds of

Speaker 3 theater and art and singing and all these other things that I was very interested in.

Speaker 3 And so I started there in seventh grade and I just really fell in love with science class.

Speaker 3 Thank you, Mrs. Susan Lundgren, if you're still out there

Speaker 3 for really like teaching us so much interesting stuff. And we were doing all these laboratory experiments where we were, you know, dissecting all kinds of things from flowers and worms to fish.

Speaker 3

And that really pulled me in. So for my seventh grade science project, I decided to try to, you know, figure out.

how sight works, how we see in the eyeball, what the eyeball is structured like.

Speaker 3 And so, you know, I read all about it and my dad went with me and he basically got a bunch of cow eyeballs harvested out of some cows who had been slaughtered and

Speaker 3 and we brought home this bag of eyeballs uh for me to dissect uh and i put it in the refrigerator and my poor grandmother came to visit and uh you know was like what's this in the refrigerator and realized it was a bag full of eyeballs but i did go on to take those eyeballs apart and really uh you know try to figure out what are these different parts how do they relate to the model i have here and what is this role role they're playing in vision.

Speaker 3 And, you know, I really just loved to be sort of self-directed and designing my own project and kind of digging in on it, but also being accountable to share what I had learned in a more rigorous academic way at school.

Speaker 3 So I really thrived that year.

Speaker 1 I understand that you came to be deeply interested in woodworking and boat building. How did you discover this passion, Mary Helen?

Speaker 3 Oh, I always loved to build things.

Speaker 3 And, you know, growing up on this like sort of kind of

Speaker 3 little farm thing in the woods, right?

Speaker 3 You know, we built it all ourselves. So when there was a hurricane,

Speaker 3

a bunch of trees fell down and we had those turned into lumber and boards. And we had to build the fences, right, for pastures to have sheep and things in them and horses.

And we built a barn.

Speaker 3 And I was tagging along behind this elderly Yankee gentleman who was a really master builder.

Speaker 3

He was an expert in stone walls and in building things. And I was following along behind him as his assistant.

And so from there, I really got into woodworking growing up.

Speaker 3 I also got very interested in boat building. wooden boat building for a while.

Speaker 3 And I went to Russia and to Kenya, you know, different places in the world where people were building traditional wooden boats of different sorts and just was trying to work with people there, with men there, to build these things to understand how they constructed these

Speaker 3 beautiful straight boats that go, you know, that go in a line and

Speaker 3 that are controllable out of wood that squirrely mangrove. You know, I just found that really compelling.

Speaker 1

In her early 20s, Mary Helen began teaching science at a public school. The school had lots of immigrant families from Africa.

She was teaching them about evolution.

Speaker 3 What fascinated me was that the kids started to ask me questions about why when we talked about early humans and hominids, why they were always depicted with dark skin, like they looked like black people.

Speaker 3 And I remember in particular,

Speaker 3 one girl, you know, bravely raising her hand, and it just struck me that all the other kids were kind of pushing her on, like, yeah, yeah, ask the question, asking me, why is that the case?

Speaker 3 Why do these early hominids always, why are they depicted with dark skin? And of course, they were on the equator where without dark skin, you would fry, right?

Speaker 3 You would have skin cancer, you'd be sunburned.

Speaker 3 And I think it was a turning point moment because the kids suddenly realized that the concept of evolution and of adaptation to your environment was applying to them as well in that context.

Speaker 3 They were seeing themselves adapt to a new environment. They were looking around at each other and seeing how they were different from one another.

Speaker 3 And they realized that the reasons we are the way we are is something to do with where we come from and how we've adapted ourselves to fit into the world and to flourish in the spaces in which our ancestors came from.

Speaker 3 And that became the entree into conversations about race, about identity, but also about individual variability, about the ways in which development and experience shape who you are.

Speaker 1 I understand that after this experience in the classroom, these students also became more engaged with the the science.

Speaker 1 They actually wanted to learn more because now they're not just learning about abstract concepts, they're learning about things that they feel they have a direct connection to.

Speaker 3 Yeah, they became very deeply interested, some of them,

Speaker 3 in really the ways that science could help them explore the world. I remember one girl who went for the first time, we were kind of near the beach, but she had never been to the coast before.

Speaker 3 And her parents took her on a weekend excursion to the beach, and she came back eagerly on Monday morning with a coffee can with snails in it and was showing me like, look, they're alive.

Speaker 3 Like these things were at the beach. So I think they really took some of the concepts and tried to use that approach to explore their world and that was incredibly powerful.

Speaker 1 So even as your students were, you know, using the science and thinking about ways that the science could apply to their lives, I also see you as a young teacher basically looking at these students and saying, some light bulb has gone off here.

Speaker 1 You know, these students were perhaps not as engaged earlier, but now their eyes are alight with excitement. They're basically trying to apply this to their own lives.

Speaker 1 At what point did you have the insight that you were seeing some important clue to the science of engagement?

Speaker 3 I mean, kids were running into my classroom at, you know, seven o'clock in the morning with a can of snails and some seawater and saying like, look, look, they're alive, right?

Speaker 3 I think the engagement really showed itself in the fact that kids were running off on their own, designing their own things and trying to use the resources I was providing them to do the stuff they were imagining.

Speaker 3

We filled the course with projects. I gave kids a huge amount of leeway in what kinds of activities they would do.

Like I set out a goal, all right? We're studying astronomy now.

Speaker 3 Here's what it looks like. But then different kids had to figure out for themselves what did they want to do in that space.

Speaker 3 And I really kind of tried to throw the ball back in their court and make them in in charge of deciding what they want to do in this space. How were they going to design this project I'd suggested?

Speaker 3 You know, and I was teaching them to use the microscopes that I found in the closet. I was teaching them to use some of the other scientific instrumentation that we had floating around.

Speaker 3 And then they were designing activities for themselves,

Speaker 3 you know, that riffed off of the things I was introducing them to in the class.

Speaker 1 What is it that makes the very same person bored and unmotivated in one setting and aflame with curiosity in another?

Speaker 1

When we come back, searching for the magic recipe for deep engagement. You're listening to Hidden Brain.

I'm Shankar Vedanta.

Speaker 1 Support for Hidden Brain comes from Wealthfront. It's time your hard-earned money works harder for you.

Speaker 1 With Wealthfront's cash account, earn a 3.5% APY on your uninvested cash from program banks with no minimum balance or account fees.

Speaker 1 Plus, you get free instant withdrawals to eligible accounts every day, so your money is always accessible when you need it. No matter your goals, Wealthfront gives you flexibility and security.

Speaker 1 Right now, open your first cash account with a $500 deposit and get a $50 bonus at wealthfront.com slash brain.

Speaker 1 Bonus terms and conditions apply cash account offered by wealthfront brokerage LLC member FINRA SIPC not a bank the annual percentage yield on deposits as of November 7th 2025 is representative subject to change and requires no minimum funds are swept to program banks where they earn the variable apy

Speaker 1 Support for Hidden Brain comes from Masterclass. Looking to grow, learn, or simply get inspired? With Masterclass, anyone can learn from the best to become their best.

Speaker 1 For as low as $10 a month, get unlimited access to over 200 classes taught by world-class business leaders, writers, chefs and more. Each lesson fits easily into your schedule.

Speaker 1 Watch anytime on your phone, laptop or TV or switch to audio mode to learn on the go. 88% of members say Masterclass has made a positive difference in their lives.

Speaker 1 Masterclass, where the world's best, teach you how to be your best. Masterclass always has great offers during the holidays, sometimes up to as much as 50% off.

Speaker 1

Head over to masterclass.com/slash brain for the current offer. That's up to 50% off at masterclass.com/slash brain.

Masterclass.com/slash brain.

Speaker 1 This is Hidden Brain. I'm Shankar Vedanta.

Speaker 1 Mary Helen Emodino-Yang is a psychologist and neuroscientist at the University of Southern California. She studies what makes students engaged and motivated, or disengaged and disaffected.

Speaker 1 Mary Helen, as a way of seeking answers to the questions raised by your own experiences of learning and teaching, you became a researcher working under the eminent neuroscientist Antonio De Masio.

Speaker 1 The two of you were attempting to understand engagement on a neurological level. Now, he had tried various ways of evoking engagement in the lab, but nothing seemed to be working.

Speaker 3 Yeah, so Antonio, when I first met him and Hanna, his collaborator and wife, were deeply interested in trying to understand how the human brain creates engagement and emotion around ideas, around social relationships and values and beliefs.

Speaker 3 And it was remarkably difficult to genuinely elicit those kinds of complex feelings in a laboratory setting. What ended up working just remarkably well

Speaker 3 was to bring together stories of real people's lives from around the world, people in a variety of complex situations, and compose these stories into little mini documentaries that I would share with the participants in our experiments in a private two-hour long interview where I would show them a small two minute to five minute documentary and tell them the story of someone's situation and then just ask them, how does this person's story make you feel?

Speaker 3 And from that, people began to really start to actively engage with and show us, exteriorize their own meaning-making process, the way in which they made sense of what they'd heard and and learned, and then went from there to begin to tell stories about what it meant to them and how they felt about it.

Speaker 3 And we moved people into the MRI scanner. after that and scanned their brain activity.

Speaker 3 We also recorded the activity in their bodies, their heart rate, their breathing, right, called psychophysiological recording at the same time.

Speaker 3 And we had them watch the stories again in the scanner and push buttons in real time to tell us how emotionally engaged they were with that story at that moment.

Speaker 3 And what we were able to do was design a method in which we could relate patterns of brain activity and body activity to

Speaker 3 expressions of emotional engagement that they are subjectively telling us they're having in real time and look at how those patterns were related to the ways in which they made meaning of the story and narratized their own experience of thinking about the story in the interview.

Speaker 1 So, one of the video clips you showed was of Malala Yousaf Sai, who described what it was like to seek an education in a region of Pakistan that was under the control of the Taliban.

Speaker 4 In the war, the girls are going to their schools freely and there is no fare. But in Sabat, when we go to our school, we are very afraid of the Taliban.

Speaker 3 He will kill us, he will throw acid on our face, and he can do anything.

Speaker 1 So you showed this video to one teenager named Isela. How did it make her feel? What did she say, Mary Helen?

Speaker 3 What Isla said, I think, was quite extraordinary and turned out to reveal a kind of pattern of thinking that many adolescents engaged in different ways and that we discovered was very important to both their brain growth and their social growth.

Speaker 3 What Estella said was first along the lines of, well, this story makes me feel very upset.

Speaker 3

It's going to be so difficult for her. She wants to be a doctor, but it's very difficult because she's not allowed to go to school.

And that's frightening and it makes me sad. But then she paused.

Speaker 3 And that pause is very important neurologically.

Speaker 3 because we think what's happening is she's shifting herself into another mode of engagement where she's leveraging systems of the brain that are involved in consciousness, in autobiographical memory, in storytelling, and beliefs and values.

Speaker 3 And what she said next was astounding. She said, it's crazy how it's that powerful.

Speaker 3 She says something like, it makes me think about my own journey in education and how I want to go to college and hopefully be a scientist someday, right?

Speaker 3 So she was likening her own experience to that girl's experience to see the similarity.

Speaker 3 But then she moves even beyond that and says, I guess what really really hits me like what the emotion is about now is how not everyone's able to get this chance to go forward with their life and get an education and do what they want to do with their life and she says it's not right

Speaker 3 she moves from analyzing this one girl sad situation which is very difficult and makes her sad to this much more powerful story about what it means for what's right in the world, what happens, what shouldn't happen, what could happen, and who she and that girl both are in the space of the broader world and what that means for what's right.

Speaker 3 She has invented morality out of a story that was a specific example.

Speaker 1 What makes this powerful is, of course, she is relating the story she is hearing to her own life.

Speaker 1 So she's not just seeing it as this other girl's story over there, but she's saying, this is my story too.

Speaker 3 She's saying it's my story too, but she even goes beyond that. She goes all the way toward the end and says, it's not right.

Speaker 3 It makes me feel upset that other people who live in certain parts of the world where they don't want people to learn are trying to hold them back, right?

Speaker 3 She starts to understand that both she and this girl are part of an even bigger world. So she goes from that girl to her own story to something even bigger than the two of them.

Speaker 3 And she ends by saying, everyone everywhere should have the chance. I mean, all human beings should be able to live free and choose their life future.

Speaker 3 So she has invented an idea, a belief, a value about how the world should be for everyone.

Speaker 3 From explaining and making sense of one girl's story, relating it to her own story, relating it to the possible future stories she had hoped to invent for herself, and from there, thinking about what's right or good or possible everywhere for everyone.

Speaker 1

Students like Isela connected with these stories in a way that went beyond the mere facts. You came to call this kind of engagement transcendent thinking.

What do you mean by the term?

Speaker 3 Isla engaged in this thing we're calling transcendent thinking because her thinking moved from the current context

Speaker 3 and transcended that context to think also about what these examples mean for bigger ideas, for what's right or good, for how institutions work, for the intentions behind the institutions and the settings and the situations that she learned about, for the values, the morals, the beliefs, for the possible futures, for the historical interpretations, for the identities that they invoke.

Speaker 3 Kids did this in many different ways, but The heart of transcendent thinking is that kids became deeply engaged with thinking about something bigger than what was directly in front of them.

Speaker 1 You ran a similar kind of study with teenagers in urban Los Angeles, and you asked them to think about crime in their neighborhoods. Tell me about that study and what you found there, Mary Helen.

Speaker 3 Right.

Speaker 3 So we asked kids who were not involved in any kind of criminal activity, who were not under any disciplinary action at school, who were passing all of their classes, who were from stable home situations.

Speaker 3 So kids who were, you know, doing fine, as my grandmother would have said, right?

Speaker 3 We asked those kids about the things that they'd witnessed and seen in their neighborhoods. And they told us about a range of scary, dangerous criminal activity of various sorts.

Speaker 3 But we didn't stop there.

Speaker 3 We then went through with them and said, okay, so you said you saw a drug deal, or you said you saw somebody get arrested, or you said you saw somebody vandalize something, or somebody get in a fight.

Speaker 3 Why do you think that happened? And how do you think the different actors in that scenario felt? And

Speaker 3 how do you think the cop felt? How do you think the little kid watching felt, right? And then we asked them a really pivotal question. We said,

Speaker 3 imagine you were in charge, and the people in your neighborhood who run things

Speaker 3 would do whatever you asked them to do as the new policy to try to make your neighborhood a better, safer place. What would you advise them to do?

Speaker 3 And there, again, we saw an amazing range of answers where some kids stayed sort of in the immediate moment saying, well, these people are bad people. They do bad things.

Speaker 3 They lose control of their emotion. They get angry and they just do something before they think.

Speaker 3 And they deserve to be rounded up or punished in some way. And that's how you're going to control things, right? Or there's nothing that can be done to control it, said one kid.

Speaker 3 This is just how these people are. Stay away from them.

Speaker 3 Other kids went beyond this to say, well, I think you have to think about the bigger picture. I think you have to think about the person's history, one kid told me.

Speaker 3 He said something like, everyone has a history, everyone has a story, and that changes who they are because of the way they've lived in their life.

Speaker 3 So if we really wanted to do something to make the neighborhood better, we should think about why these people feel the way they do that they get themselves into these situations.

Speaker 3 And he went on to tell me about his own family and how he had been loved and safe, but maybe these people hadn't been.

Speaker 3 And maybe that's where we should focus our efforts if we wanted to make the neighborhood better.

Speaker 1 So in Transcendent Thinking, you are not just considering the facts in front of you, but you're trying to see how those facts connect with other facts.

Speaker 1 And perhaps more important, how individual facts are like, you know, like trees in a forest. And you're not just seeing the trees, you're actually trying to see the forest.

Speaker 3 That's right. And you're trying to understand what makes the forest go, right? You're trying to see the hidden forces that are not immediately obvious when you just look at the forest.

Speaker 3 You're trying to understand gravity and osmosis and climate, right?

Speaker 3 You're trying to understand the bigger things that are behind the forest, but that are not immediately obvious when you just look at it.

Speaker 1 Do we know what's happening in the brain when kids are engaged in this kind of transcendent thinking, Mary Helen?

Speaker 3 Yes.

Speaker 3 So when the kids moved into the MRI scanner and thought about these same stories again, we were able to look across a young person's activity profile and match up particular time periods where they were telling us they were thinking about a particular story that they had reacted to in the interview in a transcendent way, as compared to the stories they had reacted to in a more concrete way.

Speaker 3 And so what we found is that there were particular network properties of the brain that systematically came came active and deactive in this coordinated pattern that was driven by the kids' expression of strong emotion and that organized the basic networks in the brain that led to transcendent thinking.

Speaker 3 Hmm.

Speaker 1 What were these networks in the brain, Mary Helen? Describe some of these to me.

Speaker 3 So there were three main networks involved at the level that we're analyzing. Of course, the brain is infinitely complex, but these networks were the focus of our investigation.

Speaker 3 And what we found was that networks that are involved in emotion, in feeling the inside of your guts and visceral body, that tell you when your heart's pounding or that you have a stomachache, that tell you when there's a snake in your path and suddenly you should, and look where you're going, right?

Speaker 3 Those networks were active.

Speaker 3 Networks that were allowing the person to sort of focus in a goal-directed way on attending to the world and learning about what was in front of them and remembering it and sort of integrating everything that they'd heard were active early,

Speaker 3 but for the first few seconds of watching a story. But then those networks became profoundly deactivated as the kid let go of their attention into the world.

Speaker 3 And instead, networks that are more intrinsically focused, that are mapping your state of consciousness, that are involved in autobiographical memory, that are involved in transcending the current here and now.

Speaker 3 These are the networks you use to daydream and to mind wander. Those networks became concertedly active as kids were thinking about these big transcendent ideas.

Speaker 3 So what we showed was that there was a kind of active

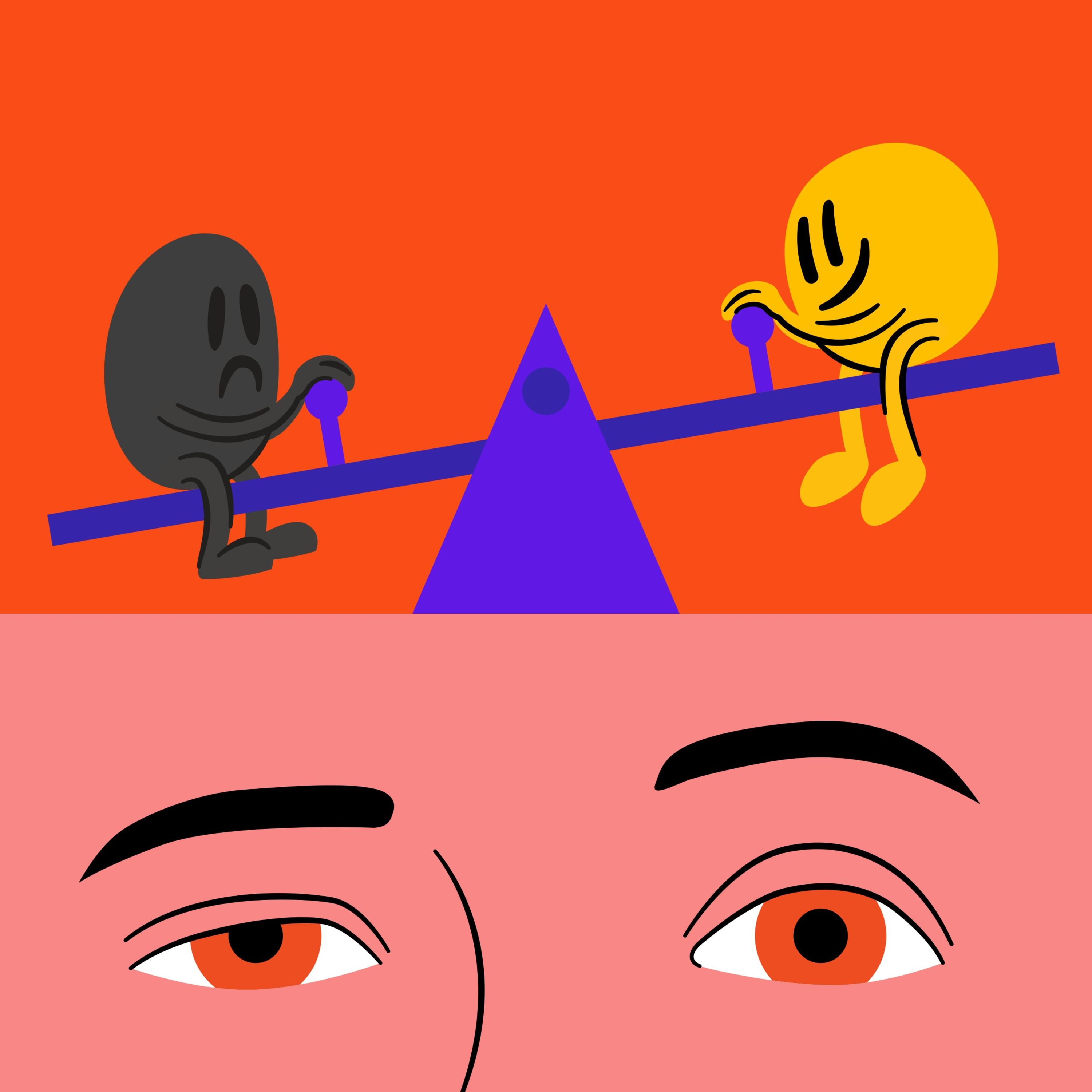

Speaker 3 dynamic trade-off between outward attention and inward reflection being driven by emotion and that sort of seesaw tottering back and forth as the young person was moving themselves into these different modes of brain activity which are corresponding to different kinds of thinking that was what we found was associated with this transcendent thinking

Speaker 1 You found that transcendent thinking was associated with more resilience in the face of adverse events. How did you discover this?

Speaker 3 We discovered that most directly with the interviews about the violence and crime that kids had witnessed in their communities.

Speaker 3 Because what we discovered was that witnessing or even knowing about crime was associated with thinning.

Speaker 3 in particular regions of the cortex that are involved in kind of outward vigilance, emotion, motivation, learning, right?

Speaker 3 Your brain is reacting to the dangerous things around it by becoming hyper-vigilant and anxious about it. And these were the same regions in the brain that become thinner among soldiers deployed

Speaker 3 as ground troops.

Speaker 3 It's also been shown to be involved in post-traumatic stress disorder among people with clinical symptomology.

Speaker 3 And we were seeing that these very same brain systems were getting thinner in our kids the more violence they knew about in their community.

Speaker 3 But what we also found is that the more kids talked in a transcendent way about what could be done about the violence, about why it happens, the more they said things like, well, everybody's got a story or a history.

Speaker 3 You have to look beyond what happened here in this situation and think about, well, how did that person get here, right? And that's where we can do something about making our neighborhood better.

Speaker 3 When kids said things like that, that kind of thinking physically was associated with thickening in the brain in these same pivotal regions for attention and pain and motivation and learning.

Speaker 3 And what we found is that thinking in these transcendent ways about the violence

Speaker 3 actually counteracted the negative effect of violence on the brain development.

Speaker 1 I understand that teenagers who engaged in this kind of transcendent thinking also reported greater life satisfaction to you?

Speaker 3 So we did a longitudinal study.

Speaker 3 That means we followed the same group of teenagers for five years and we kept bringing them back to the lab and then talking to them about who they were and having them tell us about themselves over time.

Speaker 3 And what we found that was really striking was that their transcendent thinking, the tendency that they brought to the first original interview where they were 14, 15, 16, 17 years old, right, to think about these stories that we were sharing with them in a transcendent way, to move beyond just this is a story about Malala to a story about what's right or good in the world for everyone, right?

Speaker 3 That tendency in turn predicted the future of the growth of their brain. And that growth in turn predicted identity development in late adolescence at age 19 or so, right?

Speaker 3 How much kids said, yeah, I really think about the adult I want to become and what I stand for and what my values are and what I believe in and what my purpose is.

Speaker 3 And in turn, identity development at age 19 predicted young adult life satisfaction in their early 20s.

Speaker 3 Kids' well-being and life flourishing and satisfaction in their early 20s was predicted by their tendency to engage in more of this transcendent thinking in the original interview five years before.

Speaker 3 So, kids had to show us that across time they were doing the work of growing themselves.

Speaker 1 So Mary Hennon, you've advanced the intriguing theory that transcendent thinking might effectively be the opposite of the patterns of thinking that we often see in anxiety and depression.

Speaker 1 Can you describe the contrast between these two styles of thinking?

Speaker 3 What transcendent thinking does that I think is protective for kids and deeply grows them is kids are actively, dynamically, agentically moving themselves from being here and now in the world, paying attention to those around them, reacting appropriately, getting things done, engaging with tasks, and also noticing emotionally when what really matters here is something bigger, when they can withdraw from that kind of go, go, go, do, do, do, what does it look like into a place where we think about what does this mean?

Speaker 3 And as kids are actively, dynamically shifting themselves between those ways of making meaning, they're building the neural muscle, so to speak, for mental health and for good relationships.

Speaker 3 Others who are engaging in clinical research with teens are showing that these same networks, when they're hyperactive and not flexibly trading off with one another, are involved in what appears to be the neural correlates of these mental illnesses like depression and anxiety.

Speaker 3 When kids get stuck attending to the outer world and to appearances and worrying about what's around them, we call that anxiety.

Speaker 3 When they get stuck, tipped the other way, where they're in their own head and they're thinking thinking about just stories and ruminating, that's associated with depression.

Speaker 3 What transcendent thinking does is to is kids are agentically moving themselves between these two states in appropriate ways according to the situation and what it calls for.

Speaker 3 And that is like a neural muscle that we think produces mental well-being.

Speaker 1 Mary Helen believes that the development of transcendent thinking should be at the core of of every student's education. But of course, it isn't.

Speaker 1

So many students around the world experience school today as deathly boring. When we come back, how to place engagement at the center of education.

You're listening to Hidden Brain.

Speaker 1 I'm Shankar Vedanta.

Speaker 1

Support for HiddenBrain comes from Ripple. The crypto landscape changes daily.

Keep up with some of the best launches and new tech, all in one place, on your commute.

Speaker 1 Join Ripple for a series of crypto and blockchain conversations with some of the best in the business.

Speaker 1 Learn how traditional banking benefits from the blockchain, or how your digital assets can be kept safe and secure thanks to our all-in-one custody platform,

Speaker 1 or how you can convert fear to stablecoin faster than you can get home,

Speaker 1 or how you can send a transaction halfway across the world before you make it to work,

Speaker 1 or how you're probably already using crypto technology without even realizing it.

Speaker 1 Level up your commute and join Ripple and host David Schwartz for a special series of blockchain conversations on Blockstars, the podcast: Payments, Custody, Stablecoin. It's happening with Ripple.

Speaker 1 Support for Hidden Brain comes from Brookdale Senior Living. Caring for aging parents means navigating conversations you never thought you'd have.

Speaker 1 The Grey Take is the podcast with real stories from people who have walked this path.

Speaker 1 Hosts Roy, Susie, and Emby share signs of decline they noticed in loved ones, along with thoughts on hard conversations.

Speaker 1 It's honest, practical, and reminds you nobody has this caregiving thing figured out. Search for the great tech wherever you listen to podcasts.

Speaker 1 This is Hidden Brain. I'm Shankar Vedanta.

Speaker 1 Mary Helen Imordino-Yang is a psychologist and neuroscientist at the University of Southern California.

Speaker 1 She's the author of Emotions, Learning, and the Brain, exploring the educational implications of affective neuroscience.

Speaker 1 Mary Helen, you've been studying expert teachers to determine what they know about how adolescents develop and thrive.

Speaker 1 In some ways, you're looking at examples of what social scientists might call positive deviance.

Speaker 1 You know, the math teacher who gets students to not just be proficient in math, but to actually love math. And I understand you're examining what these teachers are doing in their classrooms.

Speaker 3 Yeah, that's right. We set out to study teachers working in urban inner city Los Angeles

Speaker 3 whose administrators identified them as their quote-unquote superstars, right? The teachers who kids really love, really go to,

Speaker 3 the teachers who the administrators say are just the ones really dedicated to the kids who do really great work.

Speaker 3 And so we approached 40 of these amazing people and asked them if they would be willing to let us study them, basically to have us videotape them in their classroom and whether whether they would come to the lab and actually let us image their brains in real time while they did their work.

Speaker 3 They graded their students homeworks and gave feedback to their students and made judgments about classroom activities that they saw and told us what they thought about them.

Speaker 3

What we found was quite extraordinary. So we gave them a kid's assignment.

We said, this is Shunker's work. Grade his assignment.

And then, you know, here's Mary Helen's work. Grade her assignment.

Speaker 3 And then after a bunch of their own kids, we gave them a bunch bunch of kids assignments that we told them were not their own kids' work. And we told them we had taken those off the internet.

Speaker 3 And actually what we had done, though, is written those assignments to be matched in quality. And what we found was that first, the teachers graded the two assignments the same way.

Speaker 3 So, you know, gave Mary Helen a B over here and you gave the fake answer that we pulled off the internet from a kid that thinks like Mary Helen, also a B, right? So they knew what they were doing.

Speaker 3 But what we found was that the brain activity when they graded their own students versus students they didn't know was massively more

Speaker 3 all over the brain we see increases in activity in regions involved in motivation attention memory emotion autobiographical thinking

Speaker 3 ideas beliefs consciousness right these teachers are doing more mental, social, affective work when they're seeing their own kids' assignments than when they're seeing the assignments that are the same but by kids they don't know.

Speaker 3 What that tells us is that excellent teachers are doing work that is deeply social and emotional and effortful,

Speaker 3 even beyond what's required to just accomplish the teaching task, which is grading the assignment.

Speaker 3 So what was accounting for the difference in the brain activity in the two conditions? We asked these same teachers to provide open-ended feedback to their students.

Speaker 3 And so we said, here's your student, Mary Helen. What would you say to Mary Helen if you had a meeting with her about how she's doing? Here's your student Shankar.

Speaker 3 What would you say to Shunker if you had a meeting with him about who he's doing? And what we were looking for was to what degree do teachers

Speaker 3 actually appreciate and support actively in their feedback to their students the whole development of that young person's capacities of mind.

Speaker 3 And what we found was that the more a teacher's feedback to their students involved this kind of deep developmental support, the more activity they showed when they saw their real students' assignments versus kids' assignments that they don't know the kid.

Speaker 1

Truly great teachers do more than convey information. In fact, they do more than help students think.

They attend to where their students are emotionally, developmentally.

Speaker 1 The great teacher is asking, where is the student in their development as a human being? How can I support their growth?

Speaker 1 Mary Helen says that neuroscience shows that this question cannot be purely about intellect. It has to be about emotion as well.

Speaker 3 I think our traditional Western philosophies too often separate cognition and emotion. We think that there are cognitive skills and there are emotional skills, right?

Speaker 3 And that maybe those two things impact on each other, right?

Speaker 3

But actually, that's the wrong way to think about it. They're two different dimensions of the same thing.

Thinking is inherently cognitive and emotional always at the same time.

Speaker 3 And we can look at thinking from a cognitive lens and analyze the cognitive dimensions of what's going on. And it's important to do do that.

Speaker 3 We can look at thinking from an affective lens and analyze the emotional engagement that's going on, but actually both of those things are simultaneously

Speaker 3 happening in an integrated way always when people are alive, when they're moving through the world, adapting and engaging with the things around them.

Speaker 1 Great teachers understand, perhaps instinctively, that in order to get students to learn, they have to care about what they are learning. Emotion has to sit in the driver's seat, if you will.

Speaker 1 This is not merely an argument about how school ought to work. Mary Helen says, this is simply how the human brain is designed to work.

Speaker 3 Yeah, it turns out biology doesn't waste energy, right? We don't think about things that don't matter.

Speaker 3 Because that would be a waste of time and energy. So if you think about it this way, whatever you're having emotion about is what you're thinking about.

Speaker 3 And whatever you're thinking about, you might be able to learn about. So we need to ask ourselves as parents, as teachers, as people, what am I having emotion about?

Speaker 3 And when the emotions of school and development are about the achievements and the outcomes and the results, that is what you have a hope of learning about.

Speaker 3 When the emotions in school are about the physics, why the ball is rolling down the ramp and this hidden idea that there's this force you can't see that's pulling on the ball, and it's also pulling on us, and it's making the moon make the tides, right?

Speaker 3 When the emotion is about that powerful idea,

Speaker 3 that is when meaningful learning is about the idea, and that's when you actually build transferable knowledge that is developmentally changing the person for having learned it.

Speaker 1 You saw how this worked for one student in particular who was able to attach emotion and meaning to a philosophical problem that's known as Zeno's paradox.

Speaker 1 The paradox goes back, you know, many centuries. Imagine you're running a hundred-meter race, you first have to run 50 meters, in other words,

Speaker 1 half the distance, and then you have to run 25 meters, or in other words, half the remaining distance.

Speaker 1 And of course, you can keep doing this, which is each time you're running half of the remaining distance.

Speaker 1 And the paradox is that since there are an infinite number of half distances that you have to traverse, you will never reach the 100-meter finish line.

Speaker 1 Whereas, of course, we know that in the real world, we all routinely can run the 100-meter. So, this is the paradox known as Zeno's paradox.

Speaker 1 Tell me the story of what happened and how the student attached emotion and meaning to the paradox and came to understand it in the context of his own life.

Speaker 3 So, this is an example of a really fantastic math curriculum that's

Speaker 3 built by a school in New York City that's an alternative high school for kids who haven't passed their classes in traditional schools for whatever reason.

Speaker 3

Some of them are new immigrants to the country. Some of them have just failed in the past and not connected with school.

Some of them are in trouble.

Speaker 3 And so these teachers have designed a math curriculum that turns things on its head, right? But they actually have it right.

Speaker 3 Rather than starting with the building blocks of how to calculate things and working up, they start with big, powerful, intriguing ideas. They get kids involved with those.

Speaker 3 They choose big problems to work on. And then those problems become the space in which they learn mathematical calculation because they're so driven to understand their problem.

Speaker 3 So this one young man is describing how he had never before taken a math class and passed. And in this math class, he was given a big problem called Zeno's paradox.

Speaker 3

It's this problem that he calls walking walking to the door. You get halfway, halfway, halfway to the door.

Do you ever make it to the door? Why or why not?

Speaker 3 And he says, I got so fascinated by this problem, I had to learn fractions to solve the problem I had. And I got fascinated by ideas like asymptotes and finite and infinite.

Speaker 3 And he talks about how he's moving back and forth between being fascinated by this big idea and having to learn the calculations and the mathematical concepts to be able to satisfy his curiosity about that big idea.

Speaker 3 And as he's, we think, tilting his brain sort of back and forth from paying attention, learning about fractions, because I care about big ideas like infinity.

Speaker 3 What an amazing idea, an asymptote that you get closer and closer to something, but you never reach it, right?

Speaker 3 As he's doing that, he's tickling up, we think, the same regions of his brain that are the ones that are the kind of pivot of the attentional seesaw which are the feeling of your guts and viscera and your own self and what we think is happening is that by engaging in these in these agentic ways of moving yourself between doing the skill and thinking about the big idea and then doing the the calculations again because you care about the big idea what happens is that the after effect is you activate up these regions of the brain that are the seat of our subjective feeling of our own internal self they're the feeling of being me

Speaker 3 And the kid says, and many of the kids in this kind of curriculum say, it got relevant to my life. It mattered to my life.

Speaker 3 You've never passed a math class before. You're a new immigrant to the United States, living in poverty, and infinity got relevant to your life? And fractions?

Speaker 3 Because relevance is not necessarily simply about the direct applicability of a skill to your everyday things you need to accomplish.

Speaker 3 That's important, but that's relevance with what I would call a little R. Relevance with a big R is it feels like me to think about and understand this big, powerful idea.

Speaker 3

I'm moving through the world with a level of understanding and analysis that I didn't have before. That feels powerful.

And when you do that,

Speaker 3 the math becomes relevant to who I am.

Speaker 1 There is a philosophical shift in thinking that lies at the heart of engaging people in exploration and curiosity.

Speaker 1 It involves paying less attention to what you are teaching, whether that's algebra or civics, and more attention to the development of the human being you are trying to teach.

Speaker 1 Mary Helen calls this conceptual shift the equivalent of a Copernican revolution.

Speaker 3 So we set the cart before the horse in the way we design our curricula right now.

Speaker 3 We're thinking too much about what little learning nuggets get shoved in the cart, and we forget to think about who's the horse pulling that cart.

Speaker 3 What does that horse need?

Speaker 3 And that's, I think, the fundamental problem with the way we've designed our education system today.

Speaker 1

That's coming up next. You're listening to Hidden Brain.

I'm Shankar Vedanta.

Speaker 1

Support for HiddenBrain comes from Ripple. The crypto landscape changes daily.

Keep up with some of the best launches and new tech, all in one place, on your commute.

Speaker 1 Join Ripple for a series of crypto and blockchain conversations with some of the best in the business.

Speaker 1 Learn how traditional banking benefits from the blockchain, or how your digital assets can be kept safe and secure thanks to our all-in-one custody platform, or how you can convert fear to stablecoin faster than you can get home, or how you can send a transaction halfway across the world before you make it to work, or how you're probably already using crypto technology without even realizing it.

Speaker 1

Level up your commute and join Ripple and host David Schwartz for a special series of blockchain conversations on Blockstars, the podcast. Payments, custody, stablecoin.

It's happening with Ripple.

Speaker 1 Support for HiddenBrain comes from Superhuman. The world is buzzing with AI tools, but instead of making things easier, they've made your workflow overwhelming.

Speaker 1 You're stuck copying and pasting, context switching, and juggling too many apps. There's now a better way that outsmarts the work chaos.

Speaker 1 Meet Superhuman, the AI productivity suite that gives you superpowers everywhere you work.

Speaker 1 With Grammarly, Mail and Coda working together, you get proactive help across your workflow from writing to preparing for meetings, presentations, and so much more.

Speaker 1 Superhuman knows what you might need and offers suggestions whether you're drafting emails, creating documents, or more.

Speaker 1

There are even specialized agents designed to collaborate seamlessly and amplify your impact. Unleash your superhuman potential today.

Learn more at superhuman.com slash podcast.

Speaker 1 That's superhuman.com slash podcast.

Speaker 1 This is Hidden Brain. I'm Shankar Vedanta.

Speaker 1 Mary Helen Imordino Yang found herself deeply disengaged when she was in school. After she became an education researcher and a parent herself, the wheel came full circle.

Speaker 1 She told me a story about her own son. The story comes in two chapters, second grade and third grade.

Speaker 3 In second grade, he was so

Speaker 3 disheartened with school because he finally expressed to me that they don't study the things in school that he was interested in. I said, well, what are you interested in?

Speaker 3

He said, well, airplanes and how they work. I said, okay, here's what you should do, Ted.

You write a letter to your teacher and you explain and write a proposal in which you say, how about, right?

Speaker 3 Like I was able to study airplanes and other kids might be able to study other things that they're interested in. And you work out how this will happen, right?

Speaker 3 And so he wrote a whole proposal to his teachers that basically said, how about if every kid had the chance and the option to engage in an extra project where they could investigate on their own and explore it.

Speaker 3 They could get approval first for the topic and some guidance from their teacher. And then they could go off and study something they're interested in.

Speaker 3 And when they're ready, they could come back and they could report on that to the class. And so his teacher said, fantastic, you're welcome to do that.

Speaker 3 So he went off and began studying about airplane wings and their aerodynamic properties and all these things with my husband, his father, right, who is an aerospace engineer.

Speaker 3 And he came back and did this amazing presentation that my husband.

Speaker 3 husband had helped him design and they did together where they taught the class about how airplane wings work and the ways ways that lift operates and all these kinds of things.

Speaker 3 And he had an amazing time. The following year, he had a teacher who was very good, but she

Speaker 3 didn't understand that the purpose of school was to engage kids deeply with ideas.

Speaker 3 She thought of the kids and her as partners in the learning process, that she was giving them the information and their job was to, you know, sort of compliantly give back.

Speaker 3 And when that happened well and according to plan, that's the definition of a good student. And Ted was deeply disheartened by this approach.

Speaker 3 And it came out in

Speaker 3 his real dislike and failure to move on from thinking about this behavior chart that she had in the class, which was not.

Speaker 3 which was not in any of his other classes in the school, where she had, you know, kind of green on the top, you're doing what you're supposed to do, yellow in the middle, like you're getting in hot water, and red, meaning like, you know, you're behaving badly, right?

Speaker 3 And kids' little clips were moving up and down on this. And he finally was so upset about, and she didn't understand how if he was always on green, it was a problem.

Speaker 3

And what he wrote to her in a letter finally was that. It's like when I get to school every day, he says, I think it's a new day.

And I get there to try to learn something new and exciting.

Speaker 3 And instead I see the dot, dot, dot, bad behavior chart, right? And he says, this fact makes me very uncomfortable.

Speaker 3 And he goes on to explain how it's as if the teacher is trying to dare me to do something bad.

Speaker 3 It's like, what he's really saying is, I thought school was about ideas and learning, and you're telling me it's about compliance and behavior.

Speaker 1 What Mary Helen and her colleagues have found is that the best teachers engage the kind of transcendent thinking that we discussed earlier.

Speaker 1 Regardless of whether they are teaching chemistry or civics, history or math, they are constantly asking themselves, how can I help my students see the big ideas behind the facts I'm teaching?

Speaker 1 Mary Helen cites the example of two teachers she tracked during one of her studies.

Speaker 1 Both are gifted, but one of them is focused on skillfully transmitting information and the other is focused on growing the brains of students using the syllabus as a launch pad for transcendent thinking.

Speaker 3 We We had one teacher who invited us to see the class that he had designed as a review for his

Speaker 3

civics class, high school civics class, the review before the final exam. It was before the winter holiday.

He had a holiday playlist playing of music in the background.

Speaker 3 He had made a game where he put up on the board questions with multiple choice, and kids were in teams with whiteboards, and they had to write down what they thought their answer was, and it was timed.

Speaker 3 And he was dancing with a lightsaber to entertain them and keep them moving and the kids were all saying what do you think it is what's the answer I think it's a I think it's B and then then he would say everybody put their whiteboards up and like the answer is B and you and give me the points and they would put the points on the board right

Speaker 3 contrast that with a teacher who was teaching algebra too

Speaker 3 and

Speaker 3 what she had done around her class was explain to kids that the ways that exponential functions work, the ways that quadratic equations work, they allow you to calculate something something called exponential growth.

Speaker 3 And what she did was, as the kids were learning the math, she then assigned them to families from the neighborhood as financial planners.

Speaker 3 So they worked and wrestled with those families across the semester to get financial information about those families' hopes, to buy a home, to pay for their kids' education, those kinds of things, their income, their expenses.

Speaker 3 And the kids used their Algebra II skills to calculate the cost of owning a home, the amount they should be saving to be able to pay for their child's education someday.

Speaker 3 And they worked with real families and presented them with financial planning resources. As those kids engaged in that math, they were so deeply connected to the reason why that math matters.

Speaker 3 It empowered them to be useful members of their community, to be experts who were resources to the families in their community.

Speaker 1 And of course, at this point,

Speaker 1 the formulas for compound interest are only a means to the end. And the end is, how do I help this other family make sure that they are planning securely for the future?

Speaker 3

Yes, that's right. And at the same time, I'm actually really deeply invested in learning my math.

What often happens, I spend a lot of time talking to teachers and parents and kids.

Speaker 3 What often happens is that when teachers learn about this, they say, they first see the person with the whiteboard and the civics game and he thinks, oh, look at those kids are super engaged.

Speaker 3 Those aren't the kind of kids who normally would be engaged in this they're all answering the questions and stuff and they think that's great and then you start to show them other examples of teachers like the Algebra 2 teacher or others where the kids are calm they're thoughtful and they're assured and they act professional they are advising a family on their financial planning and the demeanor they bring to their math all of a sudden the teachers perk up and say oh

Speaker 3 I guess I knew that. Of course, I've always wanted to do that, but I didn't know how.

Speaker 3 I knew I was noticing disengagement in my kids, but I thought that the opposite of disengagement was entertainment and everybody putting their hand up and saying, oh, call on me. This is fun.

Speaker 3

I love school, which is great. That's not terrible, but it's not enough.

Deep engagement, it looks calm. It looks thoughtful.

It looks agentic.

Speaker 3 It looks like kids are actually interested in what they're studying. They understand why they're doing it, and they're deeply invested in what they're doing.

Speaker 1 I mean, in some ways, I think what I hear you saying is that this Algebra 2 teacher is actually not so much teaching Algebra II as much as a form of human development.

Speaker 3 Well, she's teaching Algebra II as a means to human development, right?

Speaker 3 In education, we've made the mistake of thinking that the quote-unquote outcome of school is quote-unquote learning, right? Learning outcomes are how we measure whether school was successful.

Speaker 3

But I would argue that learning outcomes are a misnomer. They're a red herring.

Those are incredibly important things to achieve. You must learn things in school.

Speaker 3

But that's not the ultimate purpose of school. That's the means to the ultimate purpose.

The ultimate purpose, the outcome is human development.

Speaker 3 So we have to ask ourselves, what does having learned this enable in the kids as they move forward?

Speaker 3 How does having been here and experienced this learning opportunity change who they are developmentally moving forward?

Speaker 3 How does it change their proclivities to engage with information, their dispositions to think about complex information in this field?

Speaker 3 Has it changed the way they understand and think scientifically, who they position themselves to be when they move through the world? And that is meaningful developmentally oriented education.

Speaker 3 The learning is important, it's critical, but it is not the end point.

Speaker 3 It's the means. The end point is the development, and we've neglected that.

Speaker 1 I'm wondering if one implication of this, Mary Helen, is that in some ways the range and volume of things that we typically expect students to learn in high school or college might be too much.

Speaker 1 That in some ways, if you want to get really deep engagement and really want people to go deep rather than broad, you might actually have to cover less ground than we're covering today.

Speaker 3 Yeah, I think that's partly true.

Speaker 3 But I also think that once kids develop a real disposition to learn, once they develop a curiosity and a way of approaching the academic opportunities you provide for them that really puts the agency in their pocket rather than in the adults,

Speaker 3 what happens is kids can accomplish super things.

Speaker 3 But What's true is that when we overly constrain and make them learn a broad range of things without the opportunities to really go deep, what happens is that all of the learning becomes superficial and it ends up not sticking with them anyway.

Speaker 3 What's really key for young people to develop is the disposition to deeply engage with learning and the self-awareness in the learning process to know what it feels like to really understand something, what it feels like to become an expert.

Speaker 3 You know, one way I explain this is when we look at little kids, you know, lots of us have been or had four-year-olds who got super fascinated with dinosaurs, right?

Speaker 3 They started memorizing all the names of the dinosaurs and what they ate and what kind of teeth they had and all this kind of stuff.

Speaker 3 And, you know, no one stops and says, oh, my four-year-old is really on track to becoming a paleontologist, right?

Speaker 3 What is it that they're doing? They're developing their proclivity for learning. They're experiencing a little bit of expertise.

Speaker 3 They may probably even know more about something than their parent does. How empowering is that?

Speaker 3 And they're searching out new learning about something that isn't in their immediate here and now that they have to go to museums or books to learn about.

Speaker 3 And that's the developmental nature of that learning process.

Speaker 3 But when our kids get to be teenagers, we somehow think that the learning is mainly about stashing little nuts in their head like a squirrel, right?

Speaker 3

Where it's about how many little things can you shove in there. And we forget that the point is just like with those four-year-olds, the content is important.

You need a breadth of content, right?

Speaker 3 And ways of thinking about things.

Speaker 3 But what's really important is that you learn proclivities for deeply engaging with expertise, with ideas, with evidence, with thoughtful ways of analyzing and understanding things.

Speaker 3 But we often, in mainstream secondary education, do not do this. We substitute content for developmental opportunities to learn to think.

Speaker 1 I'm wondering whether people give you pushback and say, you know, Mary Helen, what you're describing is very idealistic and would be wonderful to do in classrooms and schools.

Speaker 1

But the challenges that we're facing are at a much more basic level. You know, students are not showing up to class.

We have attendance problems. We have discipline problems.

Speaker 1 Is your recommendation, Mary Helen, something that is actually practical?

Speaker 3 Yeah, well, I got news. Like the wide real world isn't working very well for a lot of kids, right? And so we keep doubling down on starting with the basics and working our way up.

Speaker 3 And the kids are absent, right? Either mentally or haven't forbidden physically, right?

Speaker 3 That's because the design of our education system does not align with the developmental needs of young people. Human beings show up naturally with curiosity, with adaptability, with engagement.

Speaker 3 And when we lower their engagement and curiosity to tiny little building block things that you have to pass through those bottlenecks before you can get to anything interesting, you have lost them.

Speaker 3 What if we turned it around and we invite kids back to school with big ideas, with powerful projects, with opportunities to actually make change in their community, start there and work backwards.

Speaker 3 to the instrumental skills, the history, the writing, you know, the interviewing, the speaking, all of the skills that would play into their ability to do those projects.

Speaker 3 We have to put the big idea first so you engage kids and give them the power to need school. And then you say, okay, you need to know fractions, kid who's excited about Zeno's paradox.

Speaker 3

Step back, come over here, I'm going to teach it to you, right? Now you need to know it, right? You're studying about... lead in the water in Flint, Michigan.

Let me teach you some chemistry.

Speaker 3 It's going to be very useful to you trying to figure out that thing you're really deeply engaged in, right? So he set the cart before the horse in the way we design our curricula right now.

Speaker 3 We're thinking too much about what little learning nuggets get shoved in the cart, and we forget to think about who's the horse pulling that cart. What does that horse need?

Speaker 3

That's, I think, the fundamental problem with the way we've designed our education system today. It's backwards.

The building block skills follow the big, intriguing ideas and the curiosities.

Speaker 3 And then the kids need the building block skills and they come back and say, please, teacher, I want want to write a commentary about reforming the foster care system because I've lived through it and I've got some ideas.

Speaker 3 Can you remind me, what does a good topic sentence really accomplish again? Because I need people to understand what I'm trying to say. It's important.

Speaker 1 Isn't it possible that there are some things that you have to learn that in fact cannot be connected to bigger concepts or more abstract concepts, that you actually just have to do the grunt work, if you will, of learning the nuts and bolts, the blocking and tackling?

Speaker 3 The nuts and bolts and the blocking and tackling are absolutely real, and they take grit and persistence and deep effort, right? But they follow a big idea. There is no nut and bolt

Speaker 3 and grunt work that doesn't have some reason for knowing it. When kids are asking, why do I need to do this? Why do I need to know this? That represents a failing of the design of the curriculum.

Speaker 3

It should be very clear to everybody in that room why you need to know this before you start learning it. They need to know it.

They need to feel the need. And then, yes, you have to work hard.

Speaker 3

You have to have self-discipline. You have to have control.

You have to have stick-to-itiveness. And all those things are things you develop within yourself.

Speaker 3 But we're fighting an uphill battle by trying to develop those skills when there actually is no big reason why you should have to do these things that the kids are privy to.

Speaker 1 You also talk about something that effective teachers do, which is they expose young people to diverse perspectives in a way that is open-minded and experimental.

Speaker 1 And you saw this happening in a class you observed at a school in New York. Talk about what you saw and heard, Mary Helen.

Speaker 3 I think teachers can design their curricula in such a way that they invite young people into a new world of thinking in that disciplinary domain.

Speaker 3 So, in one particular class I saw, which I thought was so skillfully done, this 10th grade history teacher in a school in New York called the class, democracy is an argument.

Speaker 3 And he taught American history from the perspective of the tension that's constantly present between the needs of individuals and the needs of groups.

Speaker 3 And they examined all of American history from this tension.

Speaker 3 And by looking from this perspective, what that teacher has brilliantly done is inherently set up kids to think about about as they learn what happened and when and where and the implications of that, they're set up to look for a bigger hidden idea, which is what are the tensions behind the values and the beliefs of the various actors and how do they balance themselves and how does the tension between those lead to the unfolding of historical events.

Speaker 3 It helped the kids to think deeply about the history and also to inevitably see the lessons from history that apply in our current world now.

Speaker 1

When we come back, flipping the classroom script. You're listening to Hidden Brain.

I'm Shankar Vedanta.

Speaker 1

Support for Hidden Brain comes from Hotels.com. Make your next trip work for you.

Hotels.com's new Save Your Way feature lets you choose between instant savings now or banking rewards for later.

Speaker 1 It's a flexible rewards program that puts you in control with no confusing math or blackout dates. Book now at hotels.com.

Speaker 1

Save Your Way is available to loyalty members in the US and UK on hotels with member prices. Other terms apply.

See site for details.

Speaker 1 Support for Hidden Brain Brain comes from Whole Foods Market.

Speaker 1 With great prices on turkey, sales on baking essentials, and everyday low prices from 365 brand, Whole Foods Market is the place to get everything you need for Thanksgiving.

Speaker 1 Fresh whole turkeys start at $2.99 a pound. Explore sales on select baking essentials from 365 brand like spices, broths, flour, and more.

Speaker 1 Shop everything you need for Thanksgiving now at Whole Foods Market.

Speaker 1 This is Hidden Brain. I'm Shankar Vedanta.

Speaker 1 Mary Helen Imordino Yang is a scholar at the University of Southern California. She feels that a good part of our education system is increasingly focused on the transmission of information.

Speaker 1 Especially in the age of AI, this would seem like a prescription to become redundant very quickly. Supercomputers have read more documents, more books, more scientific papers than any human.

Speaker 1 What are the skills that will prove indispensable and irreplaceable in the years to come?

Speaker 1 The ability to step back and see connections, to see how something that is true in one context might fail in another, to integrate knowledge and skills with judgment and ethics.

Speaker 1 All of this, of course, is what Mary Helen is talking about when she talks about transcendent thinking. I asked her how she has brought these ideas to bear in her own teaching.

Speaker 3 Yeah, in my own teaching, I mean, at this point in my life, I teach parents, I teach teachers, but I teach classes for graduate students, right?

Speaker 3

What I do is I really try to engage people in their own meaning-making. I put up the data, the story.

It's like a journey. I think of the curriculum as a journey.

Speaker 3 Come with me on a journey through a way of thinking about these things.

Speaker 3 I'm going to introduce you to a whole bunch of new evidence stories and stuff, and then we're going to think together about, okay, what does this mean mean now applying it back to your own practice to your own understanding of the concepts um so there's a famous neuroscientist dan chachner who did an ex did a very uh interesting experiment uh decades ago now where he asked people a simple question how many windows are in your living room

Speaker 3 and

Speaker 3 the majority of people answer that question and you say

Speaker 3 How did you answer that question? The majority of people answer that question by recounting that I had no idea the answer unless I just happened to have bought drapes last week, right?

Speaker 3 But what I did was I closed my eyes, imagined myself in my living room and walked around and counted.

Speaker 3 And that's the way memory actually works when it's deep, meaningful, complex memory for the kinds of things we really want kids to accomplish in school.

Speaker 3 You live in the living room of that disciplinary space so experientially, richly, that you then can re-situate yourself in that disciplinary frame and walk around and count windows, so to speak.

Speaker 3 You can derive information that you never had memorized before.

Speaker 3 We forget in education that the core memory system of the brain that holds together the memories we so care about, which are semantic memories, memories for facts and information, procedural memories, memories for how to do stuff, those two kinds of memories are organized in the brain and mind by what you would call autobiographical memory.

Speaker 3 It's like the hat stand of memory that all the other stuff gets hung on.

Speaker 3 It's the experience of having been here thinking about these things, the personal, subjective, lived experience of engaging with this opportunity to learn that becomes the frame on which the information gets connected.

Speaker 3

When I teach, I try to bring people on a journey with me. And I don't make this a secret.

I tell them, this is what I'm doing.

Speaker 3 I'm going to introduce you to interesting case studies, interesting findings, interesting pieces of information, interesting videos of people that are embodying ideas that I want us to try to learn about.

Speaker 3 What do you see in this? And I establish the students as agentic, curious learners.

Speaker 3 They are the people who show up in the space like scientists trying to figure out what's the idea here and how does it square with the things I've known before and what sense does it make and that's the entry point into the curriculum rather than let me give you the basic information about the brain we're going to start with all the parts and then we'll talk about what they do and then next week we'll get into the important stuff about how it works let's just look at videotapes of people kids teachers right people learning people out in the world together and watch what's happening and then think backwards learning about, well, how is the brain and the body enabling those things to happen?

Speaker 3 And how are they looking different in these different contexts? And why? And what does this mean for how we might support learning in these different contexts?

Speaker 3 So we turn it backwards around and intrigue people with the examples first and then work backward once they have seen the example to help them think about, okay, let me tell you some of the facts about what's going on behind here now.

Speaker 3 How does that change your ability to analyze and understand what you could learn from this?

Speaker 1 I mean, it sounds almost self-evident when you put it this way, but really what you're saying is that education is actually not about the things that you're teaching students, it's actually about the students themselves.

Speaker 1 If the students are at the heart of education, if the focus is on students, what they come to love, their own understanding of themselves, their place in the world, then all the learning and the facts and the information almost come along with that, rather than starting with the facts and the learning.

Speaker 3 Yeah, this is an idea that we've been writing about and advocating for for some time.

Speaker 3 And I have a paper with several colleagues that's available on the internet called Weaving a Colorful Cloth, which is about this notion.

Speaker 3 And what we're arguing is that we need to re-center education like a Copernican shift. We're changing the perspective on the metrics and the processes that we have.

Speaker 3 So, you know, right now for so long, what we've done is we're basically standing on the earth, making the earth the center and watching the kids and the learning outcomes go by.