Doing it the Hard Way

Press play and read along

Transcript

Speaker 1

Hey there, Shankar here. I'm criss-crossing the country for a series of live shows this summer.

I'll be sharing seven key insights from the first decade of Hidden Brain.

Speaker 1 These ideas have made my life better. I think they'll do the same for you.

Speaker 1 Stops on what I'm calling the Perceptions Tour include Clearwater and Fort Lauderdale in Florida, Portland and Denver, Minneapolis and Chicago, Austin and Dallas, Boston, Toronto, Phoenix, and more.

Speaker 1 To see if I'm coming to a city near you, please visit hiddenbrain.org slash tour. If you've heard my voice for years, it's going to be fun to come see me in person.

Speaker 1 Again, that's hiddenbrain.org slash T-O-U-R.

Speaker 2 This is Hidden Brain.

Speaker 1 I'm Shankar Vedanta.

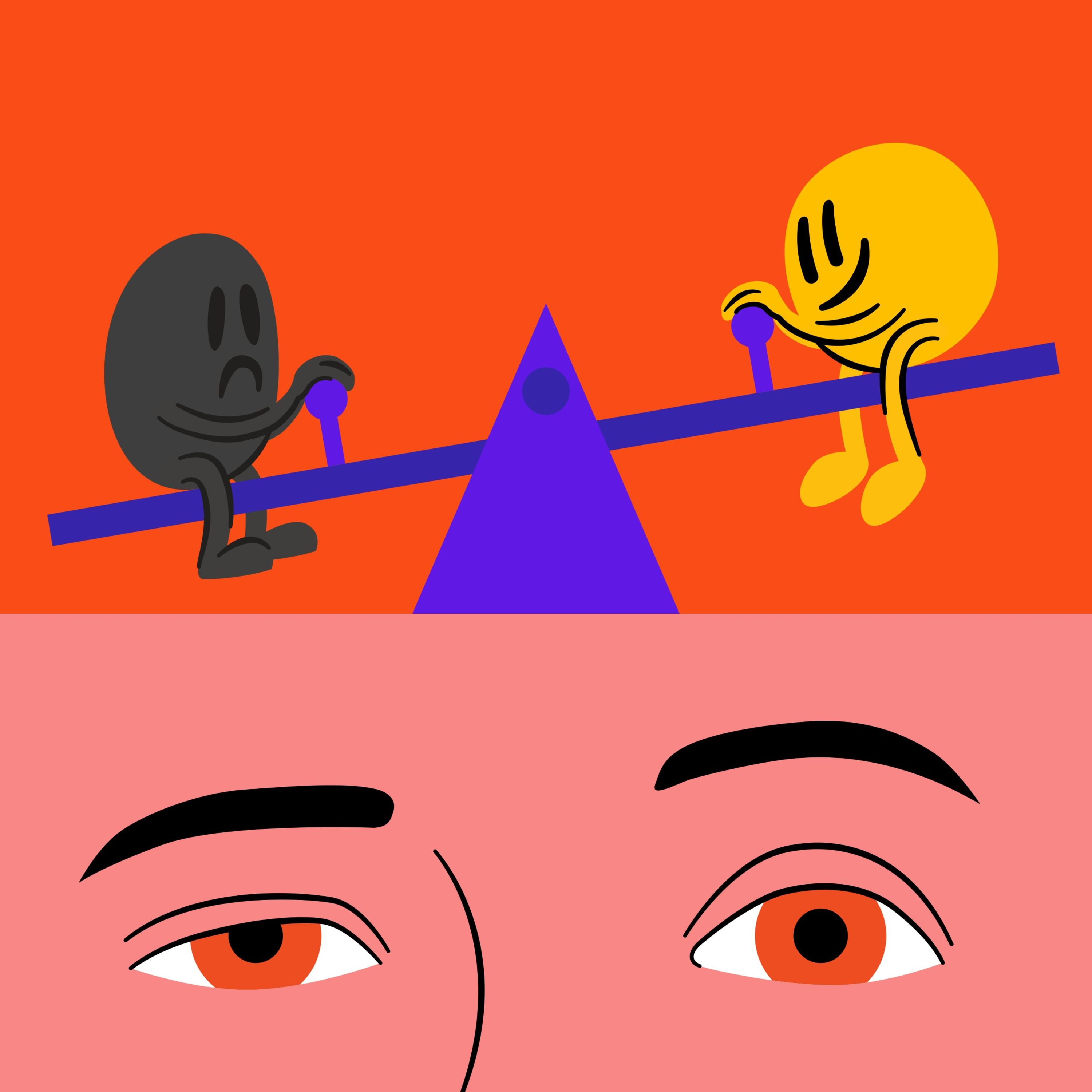

Speaker 1 Human beings are wired to seek pleasure.

Speaker 1 We all want lives filled with joy, comfort, and ease. At the same time, many of us are also curious about some forms of discomfort.

Speaker 1 We go on scary roller coaster rides, eat food so spicy it makes us cry, and we shriek in terror as we watch horror movies.

Speaker 1 Last week on the show, in the first part of a mini-series, we explored the attraction of some kinds of suffering.

Speaker 2

We do like pleasure, but we also like meaning. And we like struggle.

We want to be moral. And all of that makes our minds a lot more interesting than if we were simply seek out pleasure.

Speaker 1 Caring for a sick child, trying to run a marathon.

Speaker 1 These things involve frustration, pain, and disappointment.

Speaker 1 Unsurprisingly, if given the choice, many of us say, no thanks.

Speaker 1 Why that might be a mistake?

Speaker 1 This week on Hidden Brain.

Speaker 1 Support for hidden brain comes from Viz.

Speaker 1

Struggling to see up close. Make it visible with Viz.

Viz is a once-daily prescription eye drop to treat blurry near vision for up to 10 hours.

Speaker 1 The most common side effects that may be experienced while using Viz include eye irritation, temporary dim or dark vision, headaches, and eye redness.

Speaker 1 Talk to an eye doctor to learn if Viz is right for you. Learn more at viz.com.

Speaker 1 Support for Hidden Brain comes from WaterAid, changing the world through water. Imagine walking miles every day to collect water because your home has no taps, no toilets, no clean water.

Speaker 1 That's the reality for one in four people worldwide. Your support can help change everything for them because everything starts with water.

Speaker 1 Donate to WaterAid and your gift will be matched going twice as far. Donate at wateraid.org/slash podcast.

Speaker 1

Support for hidden brain comes from ATT. There's nothing better than feeling like someone has your back.

That kind of reliability is rare, but ATT is making it the norm with the ATT guarantee.

Speaker 1

Staying connected matters. Get connectivity you can depend on.

That's the ATT guarantee. ATT Connecting changes everything.

Terms and conditions apply. Visit ATT.com/slash guarantee for details.

Speaker 1 Have you seen those ads for vacations that tell you that all you need to do is show up? Everything after that will be taken care of. You'll just lounge by the beach or by a swimming pool.

Speaker 1

Delicious food, massages, and entertainment await you. The most effort you'll have to expand is to reach for that frozen margarita or apply a little sunscreen.

Sounds blissful, right? Well, sure.

Speaker 1 But it turns out, this is not the whole story. At the University of Toronto, psychologist Michael Inslick studies the science of motivation, effort, and reward.

Speaker 1 He's found that what we think will make us happy often does not. Michael Inslecht, welcome to Hidden Brain.

Speaker 2 Thank you so much for having me on, Shankar.

Speaker 1

Michael, social science has managed to identify only a few so-called laws of human nature. One of these was developed a little more than a century ago.

It's called the law of least effort.

Speaker 1 What is this law?

Speaker 2 This is funny because psychology, we like to say, is a young science and we don't have very many laws. I found three accounts of this law of least effort.

Speaker 2

Sometimes it's called the law of less work, sometimes the law of least effort. Sometimes it's the principle of least effort.

And three independent scientists discovered this.

Speaker 2 And this law suggests that all else being equal, every organism we ever tested, every animal we ever tested, prefers to work less than to work more for the same reward.

Speaker 1 So, the notion that people given the choice will take the less effortful path has been shown over and over again, both in real life and in psychological experiments.

Speaker 1 When we look in our own neighborhoods, for instance, we find that people routinely ignore neatly laid-out streets and walking paths and instead take shortcuts.

Speaker 1 I expect this must be the same on your university campus. They must be neatly laid out streets and you have students cutting across the grass to take the shortest path to their classes.

Speaker 2 Yes, in fact, it is a universal feature of all parks and fields across the world. And apparently it's not just humans that carve these paths, animals will carve these paths too.

Speaker 2 And the idea here is that even though there's a beautiful path laid out by a landscape architect,

Speaker 2 people and other animals like sheep, for example, they will carve out their own path with their feet connecting two spots between A and B.

Speaker 1 I remember talking to the behavioral economist Richard Thaler some time ago. He said the one rule that he's seen over and over is that people, in his words, are lazy.

Speaker 1 Given the choice, we will choose the path of least effort.

Speaker 1 And economists, in fact, have deployed this assumption to reshape the way we all save for retirement by making it automatic rather than something we have to think about.

Speaker 2

That's right. So economists, behavioral economists famously use nudges.

They use what they call choice architecture to

Speaker 2 make the virtuous option the easy option. So for example, if you struggle to save for your retirement, what about if

Speaker 2 a certain amount of money is withdrawn from your account, put into a savings account automatically without you having to lift a finger?

Speaker 2 So an interesting area where behavioral economists have discovered and have used the law of least effort to save people's lives is in the context of organ donation.

Speaker 2 So, even the simple choice that people need to make about whether they should opt into organ donation, it can be made easier where the lazy route, you know, the default is that you donate your organs and then you need to expend effort to opt out, to not donate.

Speaker 2 Giving them the easy, the lazy, the effortless route means that more people do it and more people then donate organs later.

Speaker 1 So the appeal of working less shows up in our books in popular culture almost everywhere.

Speaker 1 There are books like The Four Hour Work Week, for example, and they become bestsellers because they promise we can work a few hours a week and then kick back and relax.

Speaker 1 Do you see other examples of this in the culture, Michael?

Speaker 2 Everywhere. I will never forget.

Speaker 2 So I'm born born and raised in Canada, and I grew up with a commercial for a life insurance product that was advertising, you know, not just life insurance, but also a way to save for retirement.

Speaker 2 And they called it Freedom 55. And the idea was that at 55, if you saved enough,

Speaker 2 you could live a life of luxury. And the commercials always had someone on the beach kicking back with a, you know, a piña colada in their hand.

Speaker 2

And I remember seeing that as a child and was just in awe. I want that life.

I want to have that life.

Speaker 2 So definitely people, you know, when they think about

Speaker 2

a future that's desirable, that's fun, enjoyable, it's about relaxation. It's about being lazy.

It's about being at the beach and just kind of sitting. So we see this all the time.

Speaker 1 During the pandemic, Michael, we all heard the trend of quiet quitting and lazy girl jobs. Did you come by these memes yourself?

Speaker 2

Oh, definitely. Quiet quitting, the great resignation.

The labor force was so tight that people wouldn't necessarily get fired, even if they only worked not quite to their full potential.

Speaker 2 So yeah, you saw this trend where people were not working as hard. In Canada,

Speaker 2 we might say half-assed their job.

Speaker 2 And because,

Speaker 2

you know, employers didn't have many options, this was seen to be a trend. Hey, you too can just, you know, have your job and not work so hard.

And of course, we don't want to work so hard.

Speaker 2 We don't want to expend effort because effort is something we don't like. We are lazy.

Speaker 1 I wonder whether you've seen this in your own life. Do you see the law of least effort playing out in the choices that you make, Michael?

Speaker 2 I see it regularly. So I just returned recently from a trip to Japan, and it was toward the end of our trip.

Speaker 2 And one thing that I've, my wife and I have want to experience our, really our entire lives are the cherry blossoms that occur in the spring in Japan.

Speaker 2 And we had a long day and we'd seen a few blossoms already.

Speaker 2

And I at that point just, I just wanted to get back to the hotel room. What did I want to do in the hotel room? Not much.

I just wanted to relax.

Speaker 2 I probably wanted to surf the internet, read the news, doom scroll a little bit. My wife

Speaker 2 wisely, who just loves, is moved by beauty and plants and trees, she wisely decided to go to Yoyogi Park in Tokyo to witness beautiful cherry blossoms.

Speaker 2

And apparently they were the most beautiful that we had seen on our entire trip. And I missed it.

For what? For really for nothing.

Speaker 1 I understand this also plays out when there are social occasions at hand and you have to decide whether to go to a party or a gathering.

Speaker 2 Yes, and I should say that I'm a very extroverted person.

Speaker 2 In fact, I plans right after this to go out for beers with friends. And I find myself, despite being social, despite truly enjoying social occasions, almost invariably,

Speaker 2 I tell myself, ah,

Speaker 2

I wish I didn't have to go out tonight. I wish I could just stay in and watch, do what? Watch television, doom scroll again.

I have the impetus. I had this laziness in me to like not want to go out.

Speaker 1 The notion that people will choose the easiest, least effortful option seems to be a law of human nature. But as we have seen over and over again on the show, humans are endlessly complicated.

Speaker 1 When we come back, the effort paradox, why so many of us deliberately violate the law of least effort, and the curious relationship between pleasure and meaning.

Speaker 1 You're listening to Hidden Brain, I'm Shankar Vedanta.

Speaker 1 Support for HiddenBrain comes from Wealthfront. It's time your hard-earned money works harder for you.

Speaker 1 With WealthFront's cash account, earn a 3.5% APY on your uninvested cash from program banks with no minimum balance or account fees.

Speaker 1 Plus, you get free instant withdrawals to eligible accounts every day, so your money is always accessible when you need it. No matter your goals, Wealthfront gives you flexibility and security.

Speaker 1 Right now, open your first cash account with a $500 deposit and get a $50 bonus at wealthfront.com slash brain.

Speaker 1 Bonus terms and conditions apply. Cash account offered by Wealthfront Brokerage LLC, member FINRA, SIPC, not a bank.

Speaker 1 The annual percentage yield on deposits as of November 7th, 2025 is representative, subject to change and requires no minimum. Funds are swept to program banks where they earn the variable APY.

Speaker 3 Support for Hidden Brain comes from Masterclass. Looking to grow, learn or simply get inspired? With Masterclass, anyone can learn from the best to become their best.

Speaker 3 For as low as $10 a month, get unlimited access to over 200 classes taught by world-class business leaders, writers, chefs, and more. Each lesson fits easily into your schedule.

Speaker 3 Watch anytime on your phone, laptop or TV or switch to audio mode to learn on the go. 88% of members say Masterclass has made a positive difference in their lives.

Speaker 1 Masterclass, where the world's best, teach you how to be your best.

Speaker 3 Masterclass always has great offers during the holidays, sometimes up to as much as 50% off. Head over to masterclass.com/slash brain for the current offer.

Speaker 3 That's up to 50% off at masterclass.com/slash brain. Masterclass.com slash brain.

Speaker 2 This is Hidden Brain.

Speaker 1 I'm Shankar Vedanta.

Speaker 1 Michael Inslecht is a psychologist at the University of Toronto who studies how we think about effort and why we often gravitate to the path of least resistance.

Speaker 1 He also looks at what happens when we choose to work hard at something.

Speaker 1 Michael, we've seen that we have a natural bias against exerting effort, a bias that is then reinforced by our culture in all kinds of ways.

Speaker 1 You point out that the unpleasantness of doing things that are hard sometimes leads us to overlook the unpleasantness of doing nothing at all?

Speaker 2 That's right.

Speaker 2 So doing nothing leads us to feel bored. We find

Speaker 2 this experience unpleasant. And in fact, sometimes we will do really bad things to ourselves and other people when we're bored.

Speaker 2 There's a famous experiment where people who are left in a room with nothing other than a shock machine

Speaker 2 for a few minutes, they decide to shock themselves instead of just being alone doing nothing.

Speaker 2 We ran a study, in fact, where we gave people an option of exerting a little bit of effort, not much effort, but a little bit,

Speaker 2 or just sit there, take a 10-second holiday and do nothing. And what we found was that it was not clear that people wanted to avoid effort all the time.

Speaker 2 In fact, people preferred exerting effort if the contrast was doing nothing at all, because doing nothing is boring, and boring feels meaningless, feels purposeless, and people really don't like it.

Speaker 2 But the key to our study is that people made this choice over and over and over again, and they got to experience what the effort was like, what boredom was like, and it turns out they preferred doing something than doing nothing.

Speaker 1 So in addition to staving off boredom, exerting effort has other benefits. What is the relationship between effort and success?

Speaker 2

There are many benefits. So people who do this regularly experience more rewards.

So for example,

Speaker 2 if you want to learn the piano, the more you practice, the more you try and do the dull, repetitive work of playing your chords, practicing your chords, the better you get a piano, the more rewarding that will be to the extent that you, again, value piano.

Speaker 2 The more you study, the higher your grades,

Speaker 2

and the maybe greater entry into various vocational opportunities will be available to you. But now, this is really interesting.

This is true not just for humans.

Speaker 2 So, animals that exert effort end up flourishing more. So, insects,

Speaker 2 animals like penguins or fur seals, the more effort they exert to forage for food, to hunt for food,

Speaker 2 the healthier they are, the more varied their diet, and the more likely they are to pass on their genes to the next generation. Ants, ants show this as well.

Speaker 2 So, there's a connection between a willingness to exert effort and the rewards that you get. So, it makes sense.

Speaker 2 Exerting oneself makes makes sense,

Speaker 2 just in the sense that probabilistically, you will likely get better stuff.

Speaker 1 You have looked at the relationship between exerting effort and a feeling of competence and mastery. Describe the studies that you have conducted for me, Michael.

Speaker 2 So what we needed to do was to kind of give people dull tasks, boring tasks even, and see if the extent to which they work on them and exert effort on them, they will feel like it was worthwhile in some way.

Speaker 2 So for example, we'll give people a four-digit number and we'll have them add three to each digit of that four-digit number. Boring, meaningless, yet effortful.

Speaker 2 In contrast, we'll give another group the same four-digit number, but this time the task is not effortful. They have to add zero to that four-digit number, which of course is the exact same number.

Speaker 2 They just have to remember that number and spit it back to us. Afterwards, we ask people to what extent that task was important, to what extent it was meaningful.

Speaker 2 And what we find is that people will imbue these silly, you know, objectively meaningless tasks as being more important and more meaningful. And then afterwards, we might ask them,

Speaker 2 like, what other feelings did, did...

Speaker 2 did this task generate in them and what we found is that it led at least in some cases for people to feel like they're learning something, that they're mastering something, that they're kind of attaining some competence in something.

Speaker 2 And this is actually really important because one of the ingredients of feeling self-actualized is feeling like you're competent in the world, feeling like you can master certain domains.

Speaker 2 So perhaps exerting effort allows people kind of to play with this feeling,

Speaker 2 to attain some of these feelings that you wouldn't otherwise get.

Speaker 1 Is this a reason why when I finish building my IKEA bookshelf, I feel prouder of the bookshelf than if I just bought a bookshelf, you know, straight off the bat?

Speaker 2 Yes,

Speaker 2 there is a reason.

Speaker 2 The reason for that is that, at least after the fact, we tend to find working, exerting effort, despite it being costly, or maybe because it's it's costly

Speaker 2 we find that thing to be more meaningful we even might cherish that ikea furniture a little bit more and there's a classic study called the ikea effect whereby people who are assigned to build their own little ikea box they tend to value that box more.

Speaker 2 They think it's better and they demand more money for it than another box built by an expert. And what's funny about this is that I'm sure you've built some IKEA furniture in your life, Shankar.

Speaker 2 And you then know that oftentimes you'll build something and, hey, I've got a few extra screws here. Exactly.

Speaker 2 Right?

Speaker 2

Absolutely. Right.

So the things we build are not perfect. They're often imperfect.

Yet we think they're masterpieces and we are attached to them.

Speaker 2 And part of that story might be because we've exerted effort on them and we then imbue value and meaning and purpose to it.

Speaker 1 I understand that you had one such experience years ago on a trip to Turkey, Michael. What did you do there? And what did you end up learning about yourself?

Speaker 2

Yes, this was many, many years ago in my 20s. And we went on a hike somewhere off the Mediterranean coast in beautiful, beautiful parts of Turkey.

They call it the Turquoise Coast.

Speaker 2 And our tour guide was someone new to the job. and didn't know the route himself that well, but was an experienced hiker.

Speaker 2 So my wife and I, my girlfriend at the time, but now wife, we decided to go on this hike. We expected it to be a two to four hour hike.

Speaker 2 it ended up being like six plus hours wow in the burning heat

Speaker 2 and

Speaker 2 i remember feeling

Speaker 2 it was torture not too much the physical strain because okay i could i could walk a few more hours it was more we felt like we were lost and we felt like we didn't know where we were going and we felt like you know um we're exerting all this effort and i just want to be on the beach right now

Speaker 2 i want to be sitting and relaxing and by the end of it, we just felt mentally exhausted.

Speaker 2 But I also remember, you know, the next day at the very least, if not like, you know, immediately after, I felt like, wow,

Speaker 2 I can do that too.

Speaker 2 I too can go on a trip like this without great shoes, without great clothing, without all the sun gear that I needed. And I felt like I'd learned something about myself.

Speaker 2

I'd learned that like, okay, I'm resilient. I'm a bit tougher than, you know, tougher mentally than I thought.

And I felt like, okay,

Speaker 2 maybe,

Speaker 2 maybe I couldn't do survivor, but maybe I'm not quite as weak as I thought I was.

Speaker 1 Yeah, I mean, in some ways, you're learning that you have capacities inside you that you actually didn't know you had before.

Speaker 1 And that has to be, you know, maybe pleasurable is the wrong word, but it is sort of deeply satisfying.

Speaker 2

It's definitely satisfying, meaningful. And it was pleasurable, is definitely not the right word because it was painful.

And physically, mentally, I mean, the anguish.

Speaker 2 I remember looking at my wife being like, we were kind of like, oh my God, what are we doing here? But having gone through that pain and that effort,

Speaker 2 if it was easy, if it was just a walk on the beach, we wouldn't have left that moment with any lessons whatsoever.

Speaker 1 So you've run a number of studies where you ask people to think of a number of different tasks, routine tasks that they do in their daily life. And you find there's an interesting,

Speaker 1 in some ways, distinction between the amount of pleasure and joy that people take from tasks and the amount of meaning and satisfaction they derive from those tasks.

Speaker 1 Can you talk about this work, Michael?

Speaker 2 Yes. So we have, well, we've done a number of studies.

Speaker 2 I've already mentioned one of them where we've kind of, we give people these arduous tasks that are really meaningless, and then we find that afterwards people ascribe meaning to them.

Speaker 2 They don't necessarily think they're fun, but

Speaker 2 they do think it's meaningful. And then we also, what we did is we want to see to what extent this plays out in real tasks, not just these made-up tasks that we give them.

Speaker 2 And what we did is we kind of gave people a list of 40 to 50 kind of everyday things you could be doing, going to a party, doing your taxes, doing your homework, working out,

Speaker 2 what have you, bathing.

Speaker 2 And then we gave people this list of tasks, and then we asked them

Speaker 2

how effortful each of these tasks are, typically. We asked them how pleasurable, how much joy they derive from each of these tasks.

And then we also asked them how

Speaker 2 meaningful, how important,

Speaker 2 how significant, how purposeful each of these tasks are. And what we found was very, very interesting.

Speaker 2 We found that

Speaker 2 the more effortful a task was,

Speaker 2

the less pleasure we seemed to derive from it. But at the same time, the more effortful a task was, the more meaning we derive from it.

Effortful tasks are not necessarily pleasurable.

Speaker 2

So remember my hike in Turkey. That was not pleasurable, especially by hour six.

But later on, I described it as being meaningful and important.

Speaker 2 So joy and meaning sometimes go together, but effort breaks that apart.

Speaker 2 And it seems like effortful things, we seem to imbue them with meaning and purpose. We have this extra value that things that are merely pleasurable don't have.

Speaker 1 I'm wondering if this might explain some of the seemingly paradoxical data we get when we ask parents how much they enjoy parenting.

Speaker 1 So if you ask parents every few hours, especially parents with small children, you know, are you having a good time now? Are you having a good time now? What about now?

Speaker 1 People will often say they're not very happy. You know, they're doing chores, they're picking up after their kids, they're sleep deprived, they're exhausted, they're stressed.

Speaker 1 But then, if you also ask people, how meaningful is it to you that you have this child, that you're caring for this other human being, people report it being an incredible source of meaning.

Speaker 1 And here's another example of something that's very effortful, takes a lot of effort, might not be pleasurable on a moment-to-moment basis, but is deeply meaningful.

Speaker 2

Yes, absolutely. That's a classic one.

So, I think sometimes there's a revisionist history going on where we might, you know, cognitive dissonance pushes us to describe the arduous task of

Speaker 2

parenting as being meaningful and important. And that's a way for us to kind of say faith to some extent, to kind of say that effort was worth it.

Right.

Speaker 2 So I think sometimes the connection between effort and reward might be an illusion.

Speaker 2 It might be something, a trick we do to kind of keep us going, but not always, because oftentimes there actually are real real rewards that are connected with that effort later.

Speaker 1 Is it possible that your trip to Turkey was also the same thing here, Michael, which is that in fact it was pretty horrendous, but in retrospect, cognitive dissonance is basically reshaping your memory of the event to make it more meaningful?

Speaker 2 Absolutely. I think cognitive dissonance is a hell of a drug.

Speaker 2 I think we want to be consistent. You know, I could have been sipping Maitais or Arak in Turkey, but instead I was hiking under the hot sun.

Speaker 2 So the connection between effort and value is multiply determined.

Speaker 2 I think some of it is like a bit of a trick, an illusion, but I also think there are real sources of importance that are attached to that as well.

Speaker 1 And I suppose even if it is a trick, or what you're calling a trick, you know, if it is cognitive dissonance, post-hoc rationalizations, you know, I can't believe I made myself go through that six-hour hike.

Speaker 1 It must have been a really meaningful and important thing. As far as your mind is concerned now, it is now a meaningful thing, regardless of the mechanism that produces that meaning.

Speaker 2 Absolutely. And that's really, really important because, of course,

Speaker 2 as, you know, we're constantly facing choices about what to do and what not to do.

Speaker 2 So if I've now encoded that really arduous and difficult hike that I did in Turkey as being worth it, as being valuable, now I have a connection in my mind that effort and value go together.

Speaker 2 And so now when I make, I have a new decision to make, I'm like, yeah, I think it's difficult, but oh yeah, effort can also be valuable. It can also be important.

Speaker 2 So I start learning the value of, you know, doing of hard work, for example.

Speaker 1 I'm wondering as a college professor, you must deal with students now who have figured out that there are very easy ways of completing their assignments.

Speaker 1 They can ask ChatGPT or another AI to basically help do the work for them. And at some level, it is the case that these

Speaker 1 systems are very, very good at coming up with high quality work. But I think the story that you're telling complicates what it means for the student to actually have an AI do their homework for them.

Speaker 2

Absolutely. I think it complicates it a lot.

And in fact, we've run a study with comparing people's experience of writing an essay themselves versus prompting ChatGPT to write one for them.

Speaker 2 And what we found is like, I think, quite extraordinary.

Speaker 2

What we found is their essays were middling. They were on average when we graded them.

They got, I think,

Speaker 2 somewhere in the high 60s

Speaker 2 for their little essays. And then when they prompted ChatGPT to write, ChatGPT wrote much, much better essays, more like in the 80s.

Speaker 2 But then afterwards, when we asked these participants about their experience, people who wrote for themselves found the experience more meaningful, more important.

Speaker 2 So what this suggests to me is part of the experience of writing an essay is the experience of writing an essay,

Speaker 2 of doing it. And you might find that meaningful and important.

Speaker 2

And then you might want to do it more. And you're not just doing it just for the end goal of getting a grade.

You're doing it because you're cultivating some skill.

Speaker 2

And cultivating skill is intrinsically rewarding. As I mentioned earlier, it's meaningful.

You feel like you're alive in the world

Speaker 2 when you're doing something like that as opposed to kind of just outsourcing it to a machine. So yes, it does complicate things for students.

Speaker 1 So there's something of a paradox in all of this work, isn't there, there, Michael, which is we go to great lengths to avoid effort, to choose the path of least resistance.

Speaker 1 But as you've shown in multiple ways, doing hard things can produce benefits. It gives us pride and meaning and satisfaction.

Speaker 2 Absolutely. And a number of years ago, my colleagues and I, we talked about this paradox.

Speaker 2 We coined the term the effort paradox to describe this very thing, where on the one hand, you've got economists like Richard Thaler, but many others who look at as effort as something we need to avoid or something that people avoid, and as a result, you know, design

Speaker 2

tools and products that maximize our laziness. But at the same time, we do things all the time that require effort.

In fact, effort seems to be the only point of doing it.

Speaker 2 And it just seems odd that both of these things exist at the same time.

Speaker 1

When we we come back, one woman's vivid encounter with the effort paradox. You're listening to Hidden Brain.

I'm Shankar Vedanta.

Speaker 1

Support for Hidden Brain comes from Quince. Cold mornings, holiday plans, this is when you just want your wardrobe to be simple.

Stuff that looks sharp, feels good, and things you'll actually wear.

Speaker 1 That's where Quince comes in. This season's lineup is simple but smart and easy with Quince.

Speaker 1 $50 Mongolian cashmere sweaters that feel like an everyday luxury, denim that nails fit and everyday comfort and wool coats that are equal parts stylish and durable. And the bonus?

Speaker 1 Quince pieces make great gifts for your loved ones too. Give and get timeless holiday staples that last this season with Quince.

Speaker 1

Go to quince.com slash brain for free shipping on your order and 365 day returns. Now available in Canada too.

That's quince.com slash brain. Free shipping and 365 day returns.

Quince.com slash brain

Speaker 1 Support for Hidden Brain comes from Stripe, 1.3%.

Speaker 1

It's a small number, but with context, it's a powerful one. Stripe processed just over $1.4 trillion last year.

That works out to about 1.3% of global GDP. It's a lot, but also just 1.3%.

Speaker 1

And GDP isn't capped. Join leaders like Salesforce, OpenAI, and Pepsi who use Stripe to grow faster.

Learn more at stripe.com.

Speaker 1 This is Hidden Brain. I'm Shankar Vedanta.

Speaker 1

We are all compelled to do difficult things from time to time. Sometimes those things serve a clear purpose.

You push through years of grad school to get a degree. You go to the gym to get stronger.

Speaker 1 You eat the broccoli, even though you hate broccoli, because you know it's good for you. But there are some things we do that don't seem to serve a practical purpose.

Speaker 1 They are hard for the sake of being hard. And yet, we do them anyway.

Speaker 1 At times, we may even surprise ourselves with the lengths we'll go to in order to finish those things.

Speaker 4 My name's Mary Pan. I am a family medicine physician who lives and works in Seattle, Washington.

Speaker 1 I met Mary on a trip to the Pacific Northwest. She and some colleagues were going on an early morning hike and they were kind enough to let me tag along.

Speaker 1 As we made our way through the hilly hike, which was slushy in some places, it is Seattle and it rains a lot, Mary told me a story.

Speaker 4 Yes, so I've been running my whole adult life. It's a great way for me to de-stress and also get some exercise, get outside.

Speaker 4 And a few years ago, I

Speaker 4 wanted to do something different. I was just going through

Speaker 4 a lot of a difficult season in life. And so challenging myself to try something new, something different, seemed like a good thing to do.

Speaker 1 And so what did you have in mind?

Speaker 4 So I signed up in the fall for the next trail run that was available.

Speaker 4 And a trail run is, you know, on like a hiking trail, often in the middle of, you know, around here in the Pacific Northwest, lots of trees, nature, a place where people would go hiking,

Speaker 4

but running on that path. So, it's much more uneven.

It's beautiful often, but it's a nice way to get out into nature, out of the city.

Speaker 4 And that's how it's really different than a lot of the races I had done previously.

Speaker 1

The trail run was in December. As the date neared, Mary began watching the weather.

The night before the race, she saw that snow was forecast. This would make the run even more challenging.

Speaker 4 I woke up in the morning, looked out my window here in North Seattle where I live, and there was no snow. So I thought, okay, great.

Speaker 4 I'm going to still bundle up, get on my trail running shoes, you know, get my gloves, headband, headed out to across Lake Washington to where the start of the race was.

Speaker 4 So, as I was driving, though, about 20 minutes away to the suburb of Seattle suburb, I realized there was some more. I was seeing more and more snow as I was driving.

Speaker 4 And I went to the park and ride where the shuttle bus was picking us up to take us to the, all of the runners to the trailhead. And I realized there were patches of snow at the park and ride.

Speaker 4 And I thought, okay, well, I'm just going to keep, I'm still going to do this.

Speaker 1 Mary got on the bus. As she and the other runners were taken out to the trailhead, she looked out the window with apprehension.

Speaker 4 As we're moving up to the trailhead, there's more and more snow. And once we get up there and I get off the shuttle bus, I realize it is, there's several inches of snow on the ground.

Speaker 4

And I wasn't prepared for this. I'd never really run in snow.

I run in the rain a lot in Seattle, but not in the snow. And the other runners, no one else seemed as concerned as I did.

Speaker 4 Some of them had brought, you know, spikes to put on the bottom of their shoes. Maybe they were more experienced in running in the snow, but I wasn't.

Speaker 4

But it was beautiful. And I thought, I'm just going to do this.

I've got my gloves. I've got my layers.

I'm going to start the run and see where it goes.

Speaker 1 I'm wondering if some of your trepidation was because you are a doctor and in some ways you see people coming into the hospital after they have, let's say, not had the best run of their lives.

Speaker 1 Could that have been part of your trepidation, Mary?

Speaker 4

I'm sure it was. I tend to be a pretty cautious person.

And

Speaker 4 because I've seen so much illness and injuries in my life and in my work, and you know, I exercise a lot, but, you know, early to mid-40s, I didn't want to twist my ankle or break my leg.

Speaker 4 And as I mentioned before, trail runs are different in that they're very uneven.

Speaker 4 And so you've got to got to pay attention to that, even when just hiking.

Speaker 1 Did the possibility of just getting back on that shuttle bus and going back to your car occur to you?

Speaker 2 Uh,

Speaker 4 it didn't at the start.

Speaker 2 Um, I will tell you,

Speaker 4

I had, you know, I had bought in anticipation of this race some running shoes that are more for trails, but not for snow. Um, and I had, uh, you know, my gloves.

I run with gloves

Speaker 4 in the winter regardless.

Speaker 4 But I sort of looked around too and I think I thought well these people don't seem too concerned they some of them have the similar you know just running shoes gloves hat that I had so I I also I think thought okay I maybe I shouldn't be too concerned either this sounds like the classic story of peer pressure so tell me how the race began what happened So I started the race and I realized right away I was very tentative.

Speaker 4 Again, I'm not used to running on the snow. So I'm running much more slowly, I realize, than I normally would,

Speaker 4

much more carefully, paying attention to my steps. There were hills, uneven terrain.

The snow was very slushy at parts, other parts very icy.

Speaker 4

So I did slip a few times, but I'm with a big group at the start. We're sort of all bunched together.

And, you know, I start running and I think, okay, there's, I can do this.

Speaker 4 I'm going to be slower than I thought, but I can do this.

Speaker 4

I didn't know how far I'd gone. And I realized I was already soaked through.

My feet were, you know, know, toes were numb, fingers numb.

Speaker 4 And I hit the first aid station and I don't know how far I've gone. I think, oh, I must have gone at least, you know, six miles or more.

Speaker 4 And I asked the poor teenager there who's handing out water and these gel packs, well, how far is this? Can you tell me how far I've gone? And he asks around and he says, I think it's about 5K.

Speaker 4 And I am just dismayed because,

Speaker 4 you know, I've only run a little over three miles. I know it's taken me much longer.

Speaker 4 I'm already exhausted and freezing and my muscles are aching, I think, because I'm using different muscles to balance on this snowy trail than I normally would.

Speaker 4 And

Speaker 4 again, at that point,

Speaker 4 I'm in sort of, it's up adjacent to a neighborhood,

Speaker 4 actually, but I have a coworker who lives in that neighborhood. And he had said, hey, if you get stuck or anything, you know, feel free to just text me and I'll come and pick you up.

Speaker 4

But I didn't stop. I grabbed grabbed my water and I thought, okay, I'll just keep going and see where this goes.

And I kept going just past that 5K mark.

Speaker 1 What was it like to run where you couldn't feel your toes? And was it just your toes or was it your feet that became numb after some time?

Speaker 4 It was my toes and most of my feet and also my fingers.

Speaker 4 I'm used to running with, you know, some cold or numb toes, but it was much more pronounced. It was both my feet and my hands were completely felt really numb.

Speaker 4 And I didn't, again, I didn't feel as stable or steady on my feet.

Speaker 1 I mean, if you can't feel your toes, you can't feel your feet. That's actually quite unsafe because how do you plant your feet?

Speaker 2 It probably is.

Speaker 4 I'm not, I don't recall

Speaker 4 how I, I mean, I guess there was maybe some sensation,

Speaker 4 maybe just pain,

Speaker 4 that I was able to do that. And there were several times where I'd slip and I'd sort of, you know,

Speaker 4 gain my balance again.

Speaker 4 And I would slow down for a little bit and then I would speed up again when I think I gained a little more confidence.

Speaker 4 But right after every time I lost my balance and slipped, I was much more hesitant and cautious, I think, right after that.

Speaker 1 I'm wondering what thoughts went through your mind as you were doing this, Mary. What was your internal voice saying to you as you're going through this essentially half marathon from hell?

Speaker 4 I

Speaker 4 kept thinking,

Speaker 4 should I just stop? I think there were these moments of, should I stop?

Speaker 4 But for the most part, I, and I realize this is just a pattern in my life, whenever I meet a challenge or I commit to something, I tend to want to finish it,

Speaker 4 to complete it, even if it's very challenging and painful. I had started it, I had committed to it,

Speaker 4 and I wanted to finish it. And it was so beautiful visually, you know, it was really a gorgeous

Speaker 4 morning

Speaker 4 on that trail in many ways. But I couldn't really enjoy it fully because my body was really in a lot of pain.

Speaker 1 Mary kept going. No matter how much pain she was in, no matter how many times she slipped, she kept hearing that voice inside her.

Speaker 1 You must finish.

Speaker 1 As she reached the back half of the race, something happened that certainly made it seem like the running gods were conspiring against her.

Speaker 4 Yeah, so I'm running up the hill.

Speaker 4 I have about two miles left in the race, and I'm noticing it's warming up and the evergreen tree branches are heavy with snow and I'm starting to see some of of the snow drop around me.

Speaker 4 And as I'm running up this hill, one of the branches full of snow just dumps snow right over my head and all over me.

Speaker 4 And no one else is around at this point, and I exclaim and sort of let out a bit of a laugh too. I'm nearing the end, and it was just so ridiculous that I got soaked by

Speaker 4 this snow on the branch

Speaker 4 near the very end of the race.

Speaker 4 And at that point, I could sort of look at it and laugh at myself a little bit for even making the decision to continue on with this and the timing that I just got dumped on by the snow at the very end.

Speaker 1 It's almost as if the gods were trying to tell you something, Mary.

Speaker 4 Maybe, yes. That's true.

Speaker 4 So the rest of the race,

Speaker 4 I was able to finish the race. It was warming up, so it was very slushy snow for the most part at that point, which can also be very slick to run on.

Speaker 4 And I made it to the end and

Speaker 4 felt a lot of relief and a lot of soreness.

Speaker 4 And I, you know, grabbed my hot chocolate and got on the shuttle bus and headed back to my car.

Speaker 1 I'm wondering, looking back on it,

Speaker 1 how your accomplishment of having finished this race under these very difficult circumstances in a lot of pain, what did that tell you about yourself? What was the message you heard from yourself?

Speaker 4 I think that I can do difficult things.

Speaker 4 That's a core value of mine, is to completing and making it through challenges and difficult experiences.

Speaker 4 This is just a core of who I am,

Speaker 4 this

Speaker 4 taking on challenges. And

Speaker 4 I was thinking of, you know, I ran hurdles when I was in middle school and my first track meet, I remember I started the race, ran over the first hurdle, second hurdle, hit it with my foot, fell down, was bloody, and saw all the other runners in front of me, got up and kept going, Hit the next hurdle, fell down, got up and kept going.

Speaker 4 Hit the next hurdle, kept going, finished the race.

Speaker 4 And I remember the coach came up to me after, and I was only, you know, 12 years, 11, 12 years old, and said, wow, Mary, I've never seen anyone, you know, finish something, you know, when they're bleeding like that.

Speaker 1 I shared Mary's story with Michael Inslecht at the University of Toronto. I asked him what he made of it.

Speaker 2 I mean, I hear the effort paradox written all over that story. So

Speaker 2 first, she wanted to run a half marathon,

Speaker 2 which

Speaker 2 the act of running a marathon is a really, really puzzling thing if we come to think about it.

Speaker 2 We're running in a circle, more or less, and

Speaker 2

you know, it's painful. It's not necessarily good for you.

It's bad on your feet, bad on your knees.

Speaker 2 Yet people do this regularly. And Mary, she experienced the true hardship of running.

Speaker 2 It's, forget about it being painful. Normally, she also had snow,

Speaker 2

you know, branch with snow falling on top of her. Didn't sound like she was having a good time at all.

It sounded very unpleasant. But yet afterwards, she

Speaker 2 appraised it as this

Speaker 2 important experience,

Speaker 2 this this meaningful experience. And she even connected then to a story of herself running hurdles when she was younger.

Speaker 2 And she kind of built this story of herself as being a persistent person, a person who, you know, overcomes things.

Speaker 2 So I think, you know, these effortful situations in our life give us these like testing grounds, these testing grounds to show what we're made of.

Speaker 2 And they allow us kind of to be a hero in our own life story. And you don't get that by not running the marathon.

Speaker 2 You only get that by putting yourself in hard places, in challenging places.

Speaker 2 And that's why,

Speaker 2 you know, the economists or the psychologists who talk about, you know, the silliness of effort and how we're all lazy is not paying full attention to, you know, the rest of us and how we tell stories about ourselves.

Speaker 2 And we want those stories to be, to some extent, a hero story. And effort allows for that, allows us to be a hero in our lives

Speaker 1 effort is unpleasant and painful but effort can also be rewarding michael and other psychologists suggest that we can help other people in our lives cultivate industriousness by offering praise when the people around us display effort regardless of whether it achieves a goal that's something we can do as parents is to teach our children that trying is the the key.

Speaker 2

We want people to be rewarded for trying. So you've got someone who just kind of participated but didn't do much.

I'm not sure how much reward they need.

Speaker 2 But if they participated and they've tried and gave it their all, and who cares what the outcome is at that point? Now you're like, you tried hard and I'm going to reward you for that.

Speaker 2 So we're learning that

Speaker 2 to be industrious is rewarding. To push yourself, to try, to give it your all, to like, to tolerate that feeling, because it is not necessarily a pleasant feeling.

Speaker 2 And that's something that we can learn. And in fact, many cultures teach this.

Speaker 2 We receive all kinds of lessons about the value of trying. And we can scaffold that in our children or our students when they're trying for things.

Speaker 1 Is there any evidence that learning to be industrious in one domain transfers over to other domains?

Speaker 2 Yes, there is. In fact, there's some research that I've just done in my lab that people, in fact,

Speaker 2 exerted more effort on a brand new task that they had not experienced if previously they had learnt that effort is rewarding.

Speaker 2 So what I love about this idea is it suggests that we can learn to tolerate effort as a general thing. And the reason for that is because the feeling of effort is a generalized feeling.

Speaker 2 Yes, when I try hard on my piano, of course, there's something strictly attached to the piano and the finger movements and what have you, but

Speaker 2 the experience of effort is common.

Speaker 2 These feelings transfer. And then if we can learn that these feelings, signal reward is coming, you then become industrious.

Speaker 1 I understand that you yourself have absorbed the lesson of your research, and you did so many years ago, even before you had conducted the research, during a trip to Indonesia with your then-girlfriend, who again

Speaker 1 was the woman who became your wife. Tell me the the story of what happened on that trip michael

Speaker 2 yes so uh i'm also cognizant of i've met lots of stories around trips clearly you can see that my wife and i like to travel um and indonesia is is truly one of our our favorite places um

Speaker 2 and we had this is you know after graduate school and we'd spent this is i think probably about two and a half months now in southeast asia and uh at the end of our trip we were kind of on what i call the the paradise island of bali bali is one of my favorite places beautiful people, beautiful culture, beautiful nature.

Speaker 2 And

Speaker 2 my wife wanted to go to Java, which is the neighboring island just to the west of Bali, but it involved a long series of trips on boat,

Speaker 2 on various buses.

Speaker 2

I think it involved like over 24 hours of travel. And I just was tired.

I just, you know, the idea of sitting on a bus, being bored, this is well before smartphones and entertainment on a bus.

Speaker 2

And also, you know, the heat and it's not pleasant to be on a bus for so long. I just didn't want to do it.

But I decided, okay, let's let's just go ahead.

Speaker 2 And we then continued on to Java. We then experienced Jogjakarta, which I witnessed, you know, incredible sights there.

Speaker 2 But truly, the thing that I will never forget as long as I live is the moment I saw Mount Bromo. Mount Bromo is an active volcano on Java.

Speaker 2 And I'd never seen something like this in my life. I'd never been to the moon, as most people have and not been to, but the landscape

Speaker 2 seemed like it would be, you know, what you'd be like on the moon. And I was surrounded by volcanoes all around me,

Speaker 2

fires kind of just coming from the ground. And it was an otherworldly experience.

It was tremendous. And we spent a good 36 hours there.

there.

Speaker 2

And I now see that the effort was so worth it to see this site. And if I had not had that pain, I wouldn't have seen it.

Now, of course, maybe I'm exaggerating how beautiful it was

Speaker 2 because, again, cognitive distance can play these tricks on you. But I do think that if anyone ever gets a chance to see this, this kind of otherworldly place go,

Speaker 2 the effort was truly, truly worth it.

Speaker 2 And I do not regret that whatsoever. It was one of the highlights of my life to see that.

Speaker 1 Michael Linslecht is a psychologist at the University of Toronto. Michael, thank you so much for joining me today on Hidden Brain.

Speaker 2 Thank you so much for having me. It's been a real pleasure.

Speaker 1

Ryan Katz, Audem Barnes, Andrew Chadwick, and Nick Woodbury. Tara Boyle is our executive producer.

I'm Hidden Brain's executive editor.

Speaker 1 If you love Hidden Brain, please join our podcast subscription, Hidden Brain Plus. You'll be helping to support the research, reporting, and interviewing that go into every episode of the show.

Speaker 1 Plus, you'll have access to episodes you won't hear anywhere else. To sign up, go to support.hiddenbrain.org.

Speaker 1 If you listen to the show via Apple podcasts, you can sign up at apple.co/slash hidden brain.

Speaker 1 I'm Shankar Vedantam. See you soon.

Speaker 1 Support for hidden brain comes from the new all-electric Toyota BZ.

Speaker 1 With up to an EPA estimated 314 mile range rating for front-wheel drive models and available all-wheel drive models with 338 horsepower the toyota bz is built for confidence conveniently charge at home or on the go with access to a wide range of compatible public charging networks including tesla superchargers inside enjoy your 14-inch touchscreen and an available panoramic view moonroof learn more at toyota.com slash bz the new all-electric bz toyota let's go places

Speaker 5 you're cut from a different cloth and with bank of America Private Bank, you have an entire team tailored to your needs, with wealth and business strategies built for the biggest ambitions, like yours.

Speaker 5 Whatever your passion, unlock more powerful possibilities at privatebank.bankofamerica.com. What would you like the power to do? Bank of America, official bank of the FIFA World Cup 2026.

Speaker 5 Bank of America Private Bank is a division of Bank of America and a member FDIC and a wholly owned subsidiary of Bank of America Corporation.

Speaker 1 Support for hidden brent comes from Vitamix. Ever notice the more options we have, the less satisfied we feel? Psychologists call this the paradox of choice.

Speaker 1 In today's world, we're faced with endless options and infinite noise. It's important to cut through to what's truly essential.

Speaker 1 Vitamix blenders are that rare essential, engineered to deliver lasting performance and powerful versatility so you can create with purpose. Visit vitamix.com for the blender you need.

Speaker 6 What can 160 years of experience teach you about the future?

Speaker 6 When it comes to protecting what matters, Pacific Life provides life insurance, retirement income, and employee benefits for people and businesses building a more confident tomorrow.

Speaker 6 Strategies rooted in strength and backed by experience. Ask a financial professional how Pacific Life can help you today.

Speaker 6 Pacific Life Insurance Company, Omaha, Nebraska, and in New York, Pacific Life and Annuity, Phoenix, Arizona.