Escaping Perfectionism

Press play and read along

Transcript

Speaker 1 is Hidden Brain. I'm Shankar Vedantam.

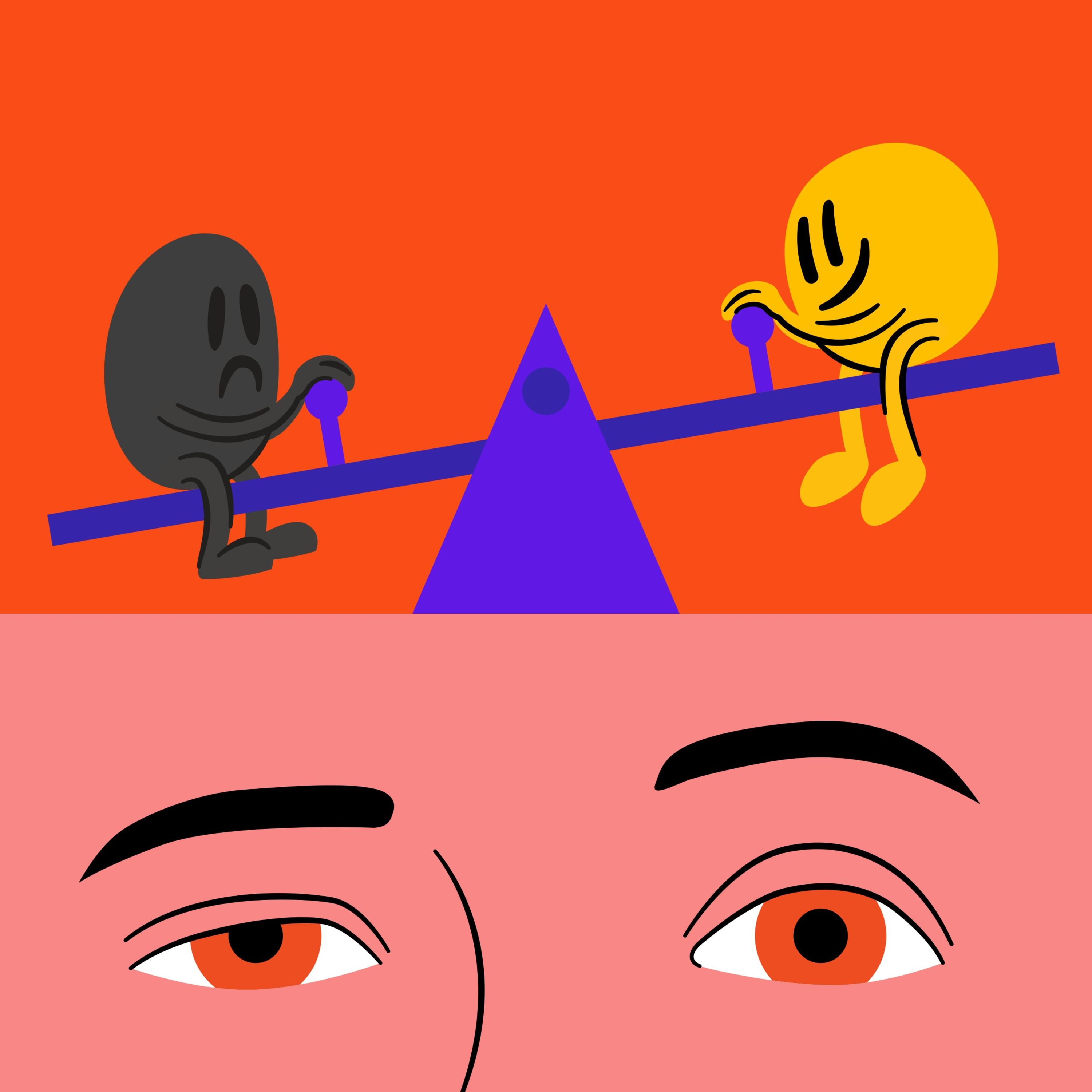

Speaker 1 They are on our TVs, on our phones and on highway billboards. Flawless, airbrushed images of beautiful people living beautiful lives.

Speaker 1 Their complexions glow, their wealth seems effortless, and their children are always smiling.

Speaker 1

All of us are surrounded by these pictures of perfection. pictures that contrast all too starkly with our own complicated, messy lives.

Social media platforms exacerbate this.

Speaker 1

Friends post pictures of their idyllic vacations. Colleagues announce promotions.

A lot of people use the hashtag Blessed.

Speaker 1 Meanwhile, divorces, demotions and despair, or the challenges of making ends meet, these show up rarely or not at all.

Speaker 1 What is the effect of the sharp contrast between the worlds we are shown and the worlds we ourselves inhabit?

Speaker 1 We may remind ourselves that what we are seeing has been airbrushed and filtered, but the contrast still burrows into our unconscious minds.

Speaker 1 Some researchers have argued that this contrast produces in us nagging feelings of inferiority, shame, and resentment.

Speaker 1 It causes us to feel we never have enough and to reach endlessly for the next ring, the next achievement, the next milestone.

Speaker 1 The costs of chasing perfection this week on Hidden Brain.

Speaker 2 A massage chair might seem a bit extravagant, especially these days. Eight different settings, adjustable intensity, plus it's heated, and it just feels so good.

Speaker 2 Yes, a massage chair might seem a bit extravagant, but when it can come with a car,

Speaker 2 suddenly it seems quite practical. The all-new 2025 Volkswagen Tiguan, packed with premium features like available massaging front seats, it only feels extravagant.

Speaker 1 Support for hidden brain comes from ADT. Putting the key under the mat when you take a vacation? That's safe-ish.

Speaker 1 It's easy to rely on safetish home security hacks, but we know they don't actually work.

Speaker 1

ADT's professionally installed systems offer peace of mind and real security with services like 24/7 monitoring and cameras you can check using the ADT Plus app. Don't settle for Safeish.

Get ADT.

Speaker 1 Visit ADT.com or call 1-800-ADT ASAP.

Speaker 1

Support for hidden brain comes from ATT. There's nothing better than feeling like someone has your back.

That kind of reliability is rare, but ATT is making it the norm with the ATT guarantee.

Speaker 1

Staying connected matters. Get connectivity you can depend on.

That's the ATT guarantee.

Speaker 1

ATT connecting changes everything. Terms and conditions apply.

Visit att.com/slash guarantee for details.

Speaker 1 F. Scott Fitzgerald's masterpiece, The Great Gatsby, describes the story of a man who desperately tried to climb the social ladder.

Speaker 1 The final lines of the novel are amongst the most famous in literature. They read, Gatsby believed in the green light, the orgiastic future that year by year recedes before us.

Speaker 1 It eluded us then, but that's no matter. Tomorrow, we will run faster, stretch out our arms farther, and one fine morning.

Speaker 1 So we beat on, boats against the current, borne back ceaselessly into the past.

Speaker 1 At the London School of Economics, psychologist Thomas Curran studies how many of us are modern versions of Jay Gatsby.

Speaker 1 He explores the psychological consequences of living in a culture that is obsessed with appearance and achievement. Thomas Curran, welcome to Hidden Brain.

Speaker 4 Thank you for having me.

Speaker 1 Thomas, you grew up in a working-class family in a small town in England.

Speaker 1 And as a teenager, you were acutely aware of the social status of two friends, Kevin and Ian, and the contrast with your own family's means. Can you paint me a picture of what that was like?

Speaker 4 Yeah, so my upbringing was one of love and support, but also material lack.

Speaker 4 We didn't have a great deal of money, and one of my earliest memories of that is going to school with the wrong backpack or the wrong pencil case, or the wrong brand of sneakers.

Speaker 4 I didn't have gadgets, like a Game Boy or a PlayStation, phones were just coming in, then I didn't have one of those either.

Speaker 4 And when I compared myself with these two characters, Kevin and Ian, who had all of those things and were able to express, I guess, their personalities and their identities with these material goods, you kind of feel like, even though this is all stupid stuff, right?

Speaker 4 It's just stuff, but it really matters to a kid, and especially if you don't have it.

Speaker 4 So as I grew older and things like cars started to come into the picture, this kind of shame really started to get really into my bones. And that was huge, actually.

Speaker 4 Cars was a massive part of this because cars are kind of the ultimate status symbol, right? You just look at how they're advertised.

Speaker 4 All my friends were bought these really super sleek cars with modifications and all the rest of it. And that was like really crushing for me.

Speaker 4

That was really embarrassing not to be able to have one too. I didn't have the freedom that they had.

I couldn't go anywhere. I was just tagged along really in the back seat.

Speaker 4 And I suppose this is where I first learned about shame, what it meant to feel ashamed and embarrassed about where I am in life and what I have.

Speaker 4 And I sort of learned that you kind of got to buy your way out of that shame in this world. And that became, I guess, an early motivation.

Speaker 1 I understand that at one point Kevin and Ian asked you what car you were going to be buying, Thomas. What did they ask you? What did you say?

Speaker 4 So they had these what we call hot hatchbacks in the UK, you know, the really fast, exciting pieces of machinery, I suppose.

Speaker 4 And everybody around the town would be asking, you know, well, what car are you going to get? And you're going to get this one, you're going to get that one, you're going to get these plates.

Speaker 4 And what about these trims and these wheels?

Speaker 4 And, you know, I used to love looking at car magazines and craving for for a car of my own and i would always say you know well i'm going to have this and i'm going to have that and when i get my car it's going to have a silver trim and chrome wheels and all of these things that everybody else was talking about

Speaker 4 i would say that one day my dad's going to come back and he's going to buy me a car or it's not going to be long now you know and i i kind of wished i hoped that that would happen but of course, unlike them, my family didn't have the means to be able to buy me these things.

Speaker 4

And it wasn't my fault. There was nothing that I could have done to change those circumstances.

But you feel in some way that you're inadequate. You're less than.

Speaker 1

So later on in life, you were determined to get ahead and you became the first in your family to go to college. You had a fearsome work ethic.

Tell me about it, Thomas.

Speaker 4 So I came through the education system actually at a really unique time. In the UK Tony Blair was the prime minister and he had a great education push at that time.

Speaker 4 This was the late 90s, early noughties.

Speaker 4 And there was a lot of financing to go to university. So I took that up and I managed to scrape my way to a local teaching college to study sport with every intention of being a PE teacher.

Speaker 4 That was going to be my ambition.

Speaker 4 And I guess you could say I was lucky really, because at my time at that teaching college, I happened to intersect with a professor who was on his way to a more prestigious university.

Speaker 4 I must have impressed him because he took me with him to do a PhD. And that was when things started to really get quite crazy.

Speaker 4 Because I remember instantly being inside this kind of hyper-competitive university environment, being surrounded by people who were just way smarter than me, more erudite, way more put together.

Speaker 4 People were pumping out publications. Some of them were even getting grant money.

Speaker 4 And in that environment, those early feelings of shame and inferiority that I kind of brought with me started to come back again in mega doses.

Speaker 4 And I think my response really looking back was to develop what I can only really describe as an urgent need to lift myself above other people through an excessive form of striving.

Speaker 4 Like

Speaker 4 made sure I was the first in the office and the last to leave and made sure people saw that. You know, I'd regularly do 80-hour weeks and I'd let everybody know in the office that I was doing that.

Speaker 4 I sent these kind of weird conspicuous emails to my academic supervisors in the early hours of the morning and sometimes last thing at night just to let them know that I'm working.

Speaker 4 And I can remember one Christmas doing a thousand words of my thesis on Christmas Day. And at that time, I felt really proud of it.

Speaker 4 You know, these are incredibly unhealthy things to do, but nevertheless, I believed if I didn't do these things, then there's no way I was going to succeed.

Speaker 1 So, you eventually achieved prominence in your field. You got a job at a top-tier university, and your new status lifted you into unfamiliar realms where you often felt out of place.

Speaker 1 You were once invited, for example, to give a high-profile speech at a fancy resort where people had paid a lot of money to attend this event. Tell me what happened, Thomas.

Speaker 4 yeah so all that work did end up paying off and i was able to elevate myself uh through the academic ladd up the up the academic ladder i should say into

Speaker 4 second tier and then elite institutions and that's when i did a very important ted talk at a resort in the us

Speaker 4 back in 2018 and

Speaker 4 And I think going to that TED talk was when I finally realized I'd sort of of made something of myself here. But nevertheless, I really felt out of place at that conference.

Speaker 4 There's people there were paying thousands of pounds. They were from, you know, you talk to them, they're from this mega firm or that mega firm or that big industry.

Speaker 4

And it was kind of overwhelming a little bit. And they sort of just carried themselves with confidence.

And again, this kind of really picked my thoughts of inferiority.

Speaker 4 And the weird thing was, I was the one on the stage.

Speaker 4 I was the one who they were there to see.

Speaker 4 I'm a bit of a perfectionist. Now, how many times have you heard that one?

Speaker 1 How did the talk itself go? Give me a sense of the preparation you put in and how the talk itself was delivered and how it was received.

Speaker 4

So the talk itself was extremely nerve-wracking. I'm not a natural speaker.

It's not something that I ever thought I would do.

Speaker 4 And I've kind of just been thrust into in a profession that kind of requires you to be pretty good at speaking so one of the things I do to combat the anxiety that's associated with that is to overthink things over prepare because in my mind that's the most fail-safe way to make sure things don't go wrong it's so important that you don't show an ounce of weakness or vulnerability because in that moment things can cascade they can spiral and when it's so public that's when you feel like your deficiencies or shortcomings are being exposed.

Speaker 4 And in the end, I was able to recite a 15-minute talk word for word without any mistakes, which was incredibly important for me. But at the same time,

Speaker 4

it wasn't the most charismatic of talks. It wasn't the most inspirational, but I did it.

And people were very polite and they applauded and I'm sure they appreciated it.

Speaker 4 But at the same time, you could tell that it wasn't quite the show-stopping talk that perhaps other people at the conference had been able to deliver. And that, you know, you do think about that.

Speaker 1 So, in the aftermath of the talk, when you sort of look back on it, did you remember sort of the polite applause? What portion of it did you end up ruminating on?

Speaker 4 I was very

Speaker 4 aware that, you know, it wasn't a rousing speech that others had delivered. And so, I wondered, you know, okay, did it look stilted? You know, was it very one-dimensional or monotonic?

Speaker 4 You know, was I able to convey convey the ideas in a way that changed people or in some way made them think differently about the topic?

Speaker 4 You know, these were the goals I had going in, but I wasn't sure in those moments where I'd actually achieved them.

Speaker 1 So your anxieties about your shortcomings reached something of a peak after a romantic relationship ended, Thomas. Tell me about that period in your life and what happened.

Speaker 4 It was a very messy breakup that happened in a really exposing way.

Speaker 4 and it was something that made me feel very humiliating and humiliated excuse me I worried about how it would look to other people I chastised myself about that breakup and what it said about me and that was turning itself into all sorts of negative beliefs about myself you know why can't you snap out of it why can't you just get through this So I felt a lot of self-loathing, a lot of shame, a lot of grief.

Speaker 4 And I went into a really dark place in those moments. And what I needed to do more than anything else was to just stop and deal with the emotional plunge that I was experiencing.

Speaker 4 But my personality wouldn't let me do that.

Speaker 4 And if anything, I was trying to push myself even harder to overcompensate for the things that are now starting to go wrong as a function of the breakup and how it impacted on my emotional well-being.

Speaker 1 Some months later, Thomas was working working in his office when he started to see flashes. He had no idea what was going on.

Speaker 4

And the flashes started to get brighter. They started to obscure what I could see.

I couldn't concentrate on the thing I was reading.

Speaker 4

I had trouble breathing. My throat became really tight.

And so I tried to get some water, but that was no use.

Speaker 4 I ran out into the open road and tried to kind of suck the fresh air, but none of it was really working and it just started to take over and this panic was starting to feed the panic and then you worry what on earth is going on am i am i dying is this it and then after a few minutes of complete meltdown i would say my body just started to come back to me i was able to regulate my breathing my heart rate came down and i was almost i suppose back in the world again and at the time you know i didn't know what on earth that was and i'm sure many of your listeners can resonate but that was a panic attack that comes from the bursting of the dam of this kind of suppressed anxiety that we're just holding back.

Speaker 4 And that panic attack was really the first of many, but it was an eye-opener for me and showed me that the way that I was, you know, approaching life, trying to achieve, trying to prove to everybody that I was good enough, was actually coming at a great expense for mental health.

Speaker 1 When we come back, Thomas explores the root of his self-doubt and self-castigation and discovers that his affliction is all too common in our modern world.

Speaker 1 You're listening to Hidden Brain. I'm Shankar Vedanta.

Speaker 1 Support for Hidden Brain comes from Loom. Are you feeling a little stuck at work lately? Stuck in too many meetings? Stuck trying to wrangle teammates just to get approvals?

Speaker 1 Get your team unstuck with video messaging from Loom by Atlassian.

Speaker 1 With Loom, you can record your screen, your camera and your voice to share video messages easily.

Speaker 1 Using video helps you and your team save time and stay connected even when you're working across time zones. So now you can delete that novel-length email you were writing.

Speaker 1 Instead, you can record your screen and share your message faster. We know everyone isn't a one-take wonder when it comes to recording videos.

Speaker 1 Loom has easy editing and AI features to help you record once and get back to the work that counts. Unstuck your process, projects and teams with video communication from Loom.

Speaker 1 Try Loom today at loom.com. That's L-O-O-M.com

Speaker 1 Support for HiddenBrain comes from BetterHelp. We've all had that epic rideshare experience.

Speaker 1

Halfway through the trip, you know their heartbreak and they know your aspirations to go find yourself in Portugal. It's human.

We're all looking for connection, for someone to listen.

Speaker 1 But sometimes, the people we spill our hearts to aren't exactly equipped to help us through it.

Speaker 1 With over a decade of data-backed experience from helping millions of people, BetaHelp matches you with a therapist based on your goals.

Speaker 1 No asking for recommendations or endless scrolling through listings. Simply answer a few questions online and you'll be matched with a therapist often in as little as 48 hours.

Speaker 1

Join over 5 million people worldwide who've trusted BetterHelp for their mental health and well-being. Get a therapist who gets you.

Visit betterhelp.com/slash hidden to get 10% off your first month.

Speaker 1 That's better HELP.com slash hidden.

Speaker 1 This is Hidden Brain. I'm Shankar Vedantam.

Speaker 1 A few years ago, an electronic trading platform ran an ad that was simultaneously funny, sad, and revealing. A young man sits on an airplane.

Speaker 1 The kid in the seat behind him kicks his tray table into the young man's backrest over and over again.

Speaker 1 Glimpsing a better world in the front of the aircraft, the young man makes his way to an open curtain. In the first-class cabin, beautiful people lounge on spacious sofas.

Speaker 1

They drink champagne in long-stemmed glasses. But just as the young man thinks he's going to be invited into the special world, the open curtain is slammed shut.

And let me play.

Speaker 1 The tagline reads, First Class is there to remind you, you're not in first class.

Speaker 1 Psychologist Thomas Curran knows all about that curtain. He has seen it in his own life, but also in the lives of his students.

Speaker 1 Thomas, your students at the London School of Economics are smart and hardworking, but many of them come to you in a state of distress.

Speaker 1 You talk about one student whom you call John, who exemplified this phenomenon. What was John's story?

Speaker 4 What I see in young people and students that come through the door is a lot of tension that's bound up in an intense need to excel.

Speaker 4 And all of my students at some level feel this, but there was definitely a vivid case in John who, I think it was a very extreme case of that intense desire and need to do things perfectly, excellently, to excel at all times.

Speaker 4 He

Speaker 4 would constantly come to me in meetings telling me that his grades weren't good enough, even though they were really high.

Speaker 4 that they weren't good enough, that he didn't feel like he was succeeding in the measure that he expected of himself.

Speaker 4 And no matter really how I tried to reconcile those things and tell him that what he's doing is exceptional, he always recasted those successes as abject failures and how he'd let himself and other people down.

Speaker 4 And this was, this was so sad because John really found it difficult to see his successes in any other way. And his justification really at all times was very simple.

Speaker 4 How could he be a success when he was trying so much harder than other people just to get the same outcomes? Well, that's the thing with being being at LSE. Everyone's exceptional.

Speaker 4 And not being able to derive any lasting satisfaction from success is really a kind of signature of the way my students interpret their experience at university.

Speaker 4 They find it difficult to deal with setbacks. And I think sometimes we misunderstand this as being fragile or...

Speaker 4 young people lacking resilience but but really it's just excessive self-imposed pressures and a deep and profound fear of failure.

Speaker 1 So Thomas, you eventually came to recognize that both you and students like John were suffering from the same affliction. What was your insight?

Speaker 4 So it became evident to me that myself, my students, and many, many people around me were struggling with something called perfectionism.

Speaker 4 A need and desire to do things perfectly and nothing but perfectly that comes from a sense of lack, a sense of inferiority, a sense of deficiency, a sense that I'm not perfect.

Speaker 4 And in order to gain approval and validation in this world that I'm worth something, that I matter, that I need to be perfect.

Speaker 1 So you've conducted a study that has track levels of perfectionism over time. What do you find?

Speaker 4 So we found recently that that perfectionism is increasing among more recent generations of young people.

Speaker 4 This was a study we did back now in 2016, 2017, essentially looking at college student data of perfectionism.

Speaker 4 So we have about 30 years worth of perfectionism data looking at various indicators of perfectionism.

Speaker 4 And we found when we ran the numbers that perfectionism was increasing and increasing really rapidly. It's up about 40% since 1989.

Speaker 4 And that's concerning because it's associated most strongly with negative mental health outcomes like depression, anxiety, self-harm.

Speaker 4 And this hard data is telling us something significant and something that we need to be paying attention to.

Speaker 1

So perfectionism is really fascinating because unlike many other flaws, many people celebrate this trait. You call perfectionism our favorite flaw.

What do you mean by that?

Speaker 4 Perfectionism is something that I think in modern society has lionized, celebrated.

Speaker 4 We know it carries self-sacrificial patterns of behavior, makes us feel a little bit miserable, but nevertheless, we also think that perfectionism is what carries us forward and makes us successful.

Speaker 4 A necessary evil, so to speak, something that if we want to get ahead, we might need a bit of perfectionism.

Speaker 1 And of course, this has become something of a joke as well, Thomas. In many job interviews, when candidates are asked to name a flaw, many of them will say, I'm a perfectionist.

Speaker 4

Yeah, that's exactly right. And recruiters...

time after time tell us that that's the most overused cliché in job interviews.

Speaker 4 And I think it says something about what we consider to be socially desirable weaknesses, that if somehow we can communicate, that we're willing to

Speaker 4 sacrifice ourselves in some way and push ourselves beyond comfort that that is something they'll see as positive something that they really want on their team or in their organization and so that speaks really to the ubiquity of perfectionism at the moment I want to spend a moment talking about what perfectionism is and what it's not because I think many of us might use the same word but mean different things by it.

Speaker 1 Many people might say perfectionism is about setting high standards and working hard to meet them. But that's very different, I think, from your definition.

Speaker 1

You say perfectionism is less about pursuing success and more about avoiding failure. One of its hallmarks is something you call a deficit orientation.

What do you mean by this term?

Speaker 4 So a lot of people associate perfectionism with really high standards. That's true.

Speaker 4 But actually,

Speaker 4 perfectionism is far, far deeper than what we see on the surface.

Speaker 4 Because what really matters is where it's coming from and where those excessive amounts of striving and high standards and go-getting attitudes that you see on the surface are coming from in the perfectionistic people is a place of lack, a sense that I'm not good enough, that I'm not perfect enough.

Speaker 4 And I need to prove to other people all the time that I'm worth something, that I matter in this world.

Speaker 4 And the way that I do that is through being perfect, because of course, if I'm perfect, I'll get their validation and that will make me feel better.

Speaker 4 That will soothe those shame-based fears of not being good enough.

Speaker 1

So two people could work very hard. They can both have high standards.

They can both care about getting things right.

Speaker 1 But one person might just be conscientious while the other person is a perfectionist. And the distinction you're drawing is really what's driving them on the inside.

Speaker 1 Are you chasing success or are you fleeing failure? But there are also some external markers of perfectionism.

Speaker 1 And when perfectionists encounter adversity, you found they often respond with shame and with guilt. Can you explain what that means, Thomas?

Speaker 4 So what we see in the lab is exactly what I experienced when I encountered that breakup in my own life.

Speaker 4 When you put perfectionistic people in stressful situations, perfectionism will

Speaker 4 aggravate the stress.

Speaker 4 So every time you go into the lab, you tell perfectionistic people to do stressful things, like maybe give a public talk or complete a competitive task against other people and in the end you say you you didn't do very well or you failed what you'll see is perfectionistic people respond with intense amounts of self-conscious emotion lots of shame lots of guilt about having slipped up in some way particularly if that slip-up is public it validates in them a sense that that fear that they're not good enough.

Speaker 4 Whereas people who score lower on the perfectionism scales, well, yes, of course, these things do have an impact on their emotional state, but it's a far less profound impact and they're able to bounce back quite quickly.

Speaker 1 You told me that after that talk that you gave, you engaged in a lot of brooding and rumination about how the talk went and you worried that it had not landed properly or what could have gone better.

Speaker 1 But you're also seeing this in the data, that perfectionists engage in a lot of brooding and rumination and revisiting things over and over again.

Speaker 4 Yeah, perfectionistic people, people who are higher in the perfectionism spectrum, what you tend to see is they also score higher on what we would call self-sabotaging thought patterns. So

Speaker 4

things like you mentioned there, worry, rumination. They're really hyper-vigilant.

about where they sit relative to others, how they're performing relative to others.

Speaker 4 They find it very difficult to exist in the moment or be mindful or appreciate successes.

Speaker 4 And so perfectionistic people really find it difficult to thrive or flourish because they're constantly worried about what's going to go wrong or how other people are doing.

Speaker 1 Now, perfectionistic people often work very hard, but one of the really curious insights that you and others have had is that they often don't pay attention to working smartly.

Speaker 1 They are sometimes indifferent to what's called diminishing productivity returns. What does this mean, Thomas?

Speaker 4 Yeah, so that's a really curious finding actually in the perfectionism literature.

Speaker 4 We know perfectionists work really hard and they push themselves well beyond comfort into a zone of declining and diminishing returns for every little bit of effort that they put in.

Speaker 4 Failure is very common among perfectionist people because the goals that they set themselves are way too high.

Speaker 4 And even if they do succeed, perfectionism really just turns those successes into dead ends because the better we do, the better we feel like we're expected to do.

Speaker 4 And so we just continually keep ourselves on tiptoes, clinging for more and more. I suppose it's like running on a treadmill that never slows down.

Speaker 4 So it's really tough, the success equation for perfectionists because they really never feel like they've ever made it.

Speaker 1 You and others have argued that perfectionists sometimes engage in what is called perfectionistic self-preservation. What is this idea, Thomas?

Speaker 4 So this is the second reason, I think, why we don't see very strong correlations between

Speaker 4 perfectionism and performance.

Speaker 4 When things start to go wrong, perfectionists do something really, really interesting. They withhold their effort in order to save face, to kind of preserve their image and their sense of self.

Speaker 4 And we've done a lot of experiments looking at this phenomenon. And one of the

Speaker 4 most illuminating those experiments is when a colleague of mine, Andrew Hill, took...

Speaker 4 people into the lab, gave them a cycling task and said, you've got to complete a certain distance in a certain amount of time.

Speaker 4 And based on your fitness, you should be able to do X amount of distance so he got them going with the task and everybody worked really hard to meet the goal and at the end he told them no matter how well they did that you failed now what's really interesting here is that after telling people they failed he asked them to do it again and that's where something remarkable happened because people who didn't have a great deal of perfectionism on that second attempt after the first failure didn't really change the amount of effort they put in if anything, it went up slightly.

Speaker 4 But the people who scored high in perfectionism did the exact opposite. They withheld their effort on the second attempt.

Speaker 4 Because the thinking in their mind is you can't fail at something you didn't try. And if I put all of myself into this first effort and still didn't make it, well, I'm not going to do that again.

Speaker 4 Because the feelings of shame and embarrassment were so intense that I just don't want to feel those things again.

Speaker 4 And so this is

Speaker 4 the perfectionism paradox, I suppose.

Speaker 4 This is that they really are so intensely fearful of that failure that when it looks like it's going to be a very likely outcome of anything that we're doing, then they take themselves away from those situations.

Speaker 4

That's incredibly self-sabotaging. It doesn't just look like complete withdrawal, by the way.

It can also come in the form of procrastination.

Speaker 4 So we'll remove ourselves from doing activities that are really difficult in the moment because the anxiety is so intense. All of those things are not at all conducive to performance.

Speaker 1 So I guess this is why you would say you would not want to have a perfectionist who is the pilot of your plane or a surgeon carrying out an operation on you.

Speaker 4 There's no way you would want someone like me flying your plane.

Speaker 4 Because if an engine suddenly craps out at 35,000 feet, you're going to need somebody who's able to... think very clearly about the procedures.

Speaker 4 There's going to be, by the way, no perfect way to get out of that situation. There's going to to be many, many good enough ways to get out of that situation.

Speaker 4 And what a perfectionist will do will search for the perfect outcome.

Speaker 4 Whereas somebody who is more conscientious, meticulous, or diligent, they'll be able to know that there are many different options that we can take.

Speaker 4 And the most important thing is to take the option that lands the plane safely. And that's the same with a surgeon.

Speaker 4 That's the same with, you know, working in a nuclear plant, any of these kind of very high-risk activities.

Speaker 4 Conscientiousness, diligence, really important qualities, but not perfection.

Speaker 1 So, Tom's research has found that there's not just one kind of perfectionism, but really three, and each type comes with its own particular kind of psychological hardship.

Speaker 1 The first might be exemplified by something that happened a few years ago to a tennis player named Mikhail Yuzhny.

Speaker 1 At one point, he was the number one player in Russia and a top 10 player in the world. During a match at the Miami Open in 2008, he missed a point and slammed his own face with his racket.

Speaker 1 After the third blow, with blood streaming down his face, he required medical attention.

Speaker 1 Would he be an example of what you would call a self-oriented perfectionist, people who subject themselves to incredibly harsh criticism?

Speaker 4

Yeah, absolutely. I saw that point actually.

I remember it well. And

Speaker 4 it was at the end of a very long rally in which really the shot that was missed was one of the easiest shots.

Speaker 4 And

Speaker 4 that intense emotion and outburst that came from a place of just complete self-loathing for the fact that having made all of these really tough shots, you couldn't make the easy one.

Speaker 4 And these are the intense expectations that self-oriented perfectionistic people hold themselves to.

Speaker 4 And the moment they fall short of it, particularly in very important situations, the self-loathing, the sense of how on earth could you have been so stupid? What on earth were you thinking?

Speaker 4 How could you have let yourself make that mistake? Can be really so intense that in the extreme cases like this one, they can engage in some really quite aggressive self-castigation.

Speaker 4 And that's that's a signature of the self-oriented perfectionist. There is just simply a lack of self-compassion and a strong sense of self-loathing.

Speaker 1 Some years ago, Thomas Amy Chua, a Yale law school professor, wrote a book called Battle Hymn of the Tiger Mother.

Speaker 1 And at one point in the book, she tells her older daughter that if her piano playing isn't perfect, she is going to take her stuffed animals and burn them.

Speaker 1 I want to play you a clip of a book interview with the author on PBS.

Speaker 12

If you read the back of your book, it explains how to be a tiger mother. There's a long list of things you didn't allow your children to do, your two girls.

Let me read a couple of them.

Speaker 12 They were never allowed to attend a sleepover, have a play date, be in a school play, complain about not being in a school play, watch TV or play computer games, choose their own extracurricular activities, get any grade less than an A, not be the number one student in every subject except gym and drama, play any instrument other than the piano or violin, not play the piano or violin.

Speaker 12 When you hear that list read to you, does it sound extreme?

Speaker 12 Well, it sounds tongue-in-cheek to me, but it doesn't sound so extreme. And you know, when I talk to a lot of immigrants or immigrants' kids, they find it hysterical.

Speaker 12 You know, they know that it's poking fun a little bit, but it really captures some truth.

Speaker 1 So that is a remarkable interview. I was really struck when the interviewer listed the number of things that Amy Chua kept her kids from doing.

Speaker 1 Now, what I'm hearing is that Amy Chua feels that some of what she wrote was over the top. But I'm wondering, Thomas, do you feel that this clip captures what you call other-oriented perfectionism?

Speaker 4 Yeah, other-oriented perfectionism is when we turn perfectionism outwards onto other people and we expect them to be perfect and nothing but perfect and we'll certainly let them know.

Speaker 4 You'll know ariented perfectionist when you meet one. They tend to be quite brash.

Speaker 4 They will let you know when things haven't gone quite to plan. And it's what we call, I suppose, what Freud would call projection, the sense that...

Speaker 4 My intense desire to be perfect is projected outwards onto you too.

Speaker 1 You know, Steve Jobs had a reputation for being like this. People described him as, you know, berating other people for not living up to his high expectations.

Speaker 1 What's the line here between someone who has high expectations and is a demanding manager or a demanding boss and somebody who is an other-oriented perfectionist?

Speaker 4 Well, the line is really the inability to accept at any time that things are good enough.

Speaker 4 Whereas, you know, someone that's demanding yes, wants high standards, yes, is also somebody who can accept and appreciate when things things have gone well, when there's been a success, and can give praise and appreciation for that.

Speaker 4 And I think that's the difference.

Speaker 1 A third type of perfectionism is known as socially prescribed perfectionism. Explain this idea to me, Thomas.

Speaker 4 Socially prescribed perfectionism is the

Speaker 4 most extreme form of perfectionism and it's a perfectionism that comes from outside a sense that everybody and all around me expects me to be perfect and they're watching and waiting to pounce if I show any form of weakness.

Speaker 4 And carrying that around of you all the time is really tough.

Speaker 4 You need to be perfect at all times. You need to make sure that your life is curated

Speaker 4 to show other people, you know, there are no weaknesses. And that is really tough to live under that microscope and to think that everybody in all times is watching.

Speaker 1 So you found that socially prescribed perfectionism might be rising fastest amongst all the kinds of perfectionism in our society.

Speaker 1 Can you talk a little bit about what the data show and why this might be happening?

Speaker 4 Essentially what we're seeing today is a rise of about 40%

Speaker 4 in socially prescribed perfectionism from the late 1980s to the present day. That's a really, really big rise which continues to increase.

Speaker 4 And it's most concerning because it's most strongly correlated with really quite negative mental health outcomes like anxiety, depression, low mood, a sense of hopelessness and helplessness, things that are really quite significant when it comes to our mental health.

Speaker 4 And I think it's indicative perhaps of what I've called a hidden epidemic of unrelenting expectations for perfection, which are kind of taking over among young people.

Speaker 1 And why do you think this might be the case?

Speaker 4 Obviously, the one that most people point to is social media and the comparative lens that social media offers us 24-7 and without escape. But it's not just images of perfection in social media.

Speaker 4 It's unrelenting pressures to excel in schools and colleges. It's the modern workplace and the intense

Speaker 4 pressures to hustle and grind. It's changing parenting practices.

Speaker 4 They're responding to pressures in schools and colleges and the more competitive landscape to get into elite college by pushing young people in the realm of education.

Speaker 4 So there's all sorts of different pressures now that are weighing on young people and they're being internalized as pressures to be perfect.

Speaker 1 When we come back, how to escape the perfectionist trap?

Speaker 1 You're listening to Hidden Brain. I'm Shankar Vedanta.

Speaker 1

Support for Hidden Brain comes from LinkedIn. The best B2B marketing gets wasted on the wrong people.

So when you want to reach the right professionals, use LinkedIn Ads.

Speaker 1 LinkedIn has grown to a network of over 1 billion professionals and 130 million decision makers, and that's where it stands apart from other ad buys.

Speaker 1 You can target your buyers by job title, industry, company, role, seniority, skills, company revenue. So you can stop wasting budget on the wrong audience.

Speaker 1

It's why LinkedIn Ads generates the highest B2B ROAs of all online ad networks. Seriously, all of them.

Spend $250 on your first campaign on LinkedIn Ads and get a free $250 credit for the next one.

Speaker 1

No strings attached. Just go to linkedin.com/slash brain.

That's linkedin.com/slash brain. Terms and conditions apply.

Speaker 13 I'm gonna put you on, nephew.

Speaker 14 All right, um, welcome to McDonald's. Can I take your order?

Speaker 16 Miss, I've been hitting up McDonald's for years.

Speaker 17 Now it's back.

Speaker 18 We need snack wraps.

Speaker 13 What's a snack wrap? It's the return of something great.

Speaker 3 Snack wrap is back.

Speaker 1

This is Hidden Brain. I'm Shankar Vedantam.

Psychologist Thomas Curran is the author of The Perfection Trap: Embracing the Power of Good Enough.

Speaker 1 Thomas, you call yourself a recovering perfectionist, and you've talked about the ways in which you're working to relinquish your perfectionism.

Speaker 1 And yet, someone looking at you from the outside, you know, would see a prominent professor with a job at a top school, someone who writes books and articles and gives talks that garner wide attention.

Speaker 1

Someone might say, you know, clearly perfectionism worked for Thomas. It got him to where he is today.

How would you respond to that?

Speaker 4 Well, clearly my perfectionism has pushed me forward in moments where I've needed it to.

Speaker 4 But the reason why I'm here is because I was very, very fortunate to come through at a time where people like me were supported to go to university, where I just so happened to meet the right professor at the right time.

Speaker 4 He took me to the right university. But without those remarkable moments of luck I wouldn't be here.

Speaker 4 The second thing to say is that I look I guess on the surface like a very successful individual and in many ways I suppose I am but I can't afford to live in the city that I work in.

Speaker 4

I don't have a house. I've had to put off things like having a family and relationships.

I've lived in countless different homes.

Speaker 4 I can't set root in communities or build a long and lasting friendship group because my life has just been essentially one long period of flux.

Speaker 4 So yes, it looks like success, but it doesn't feel like success.

Speaker 4 And when I look and reflect on this journey and how difficult it's been and the sacrifice I've had to make, I sometimes question whether I might have been better off back in my working class community with a job that gives me some sense of purpose, with a family and a house and a community,

Speaker 4 maybe I would be happier.

Speaker 1 Is it possible that for some people, perfectionism might be something they say, yes, it's a curse, yes, it's psychologically unhealthy, but yes, also, I'm glad I chose this life.

Speaker 4 I don't know if Steve Jobs was or wasn't a perfectionist, but if he was, you know, I suspect that if he was around, he would tell us you know i got to start a three trillion dollar company and yes i drove myself and everyone around me nuts but that's what i did and it was worth it would that be okay for him to say it was worth it or do we get to diagnose him from the outside no i don't think we get to speak for steve jobs at all If somebody carries perfectionism around with them and they're really successful and they, yes, they go through all of the things that I've experienced and for them that's worth it, then who who am I to tell them that that isn't the case all I can say from what I understand about the work that I've done and my own experiences is that perfectionism carries a really heavy cost and that actually there's plenty of evidence that we can be just as successful if not more successful and not carrying around the emotional baggage that we carry around with perfectionism

Speaker 1 One of the people who might fit that bill is the writer Margaret Atwood. She's written nearly nearly the equivalent of a book a year over six decades.

Speaker 1

When asked how she does it, she says, I'm not a perfectionist. That's one clue.

So it's possible you can be very productive and get a lot of things done and not be a perfectionist.

Speaker 1 In fact, it might even be easier to get a lot of things done when you're not a perfectionist.

Speaker 4 And you'll be a lot more happy to.

Speaker 4 I think Margaret Atwood is a great example of someone who can combine a desire, a joy, a real sense of purpose and vocation in what she does, i.e.

Speaker 4 writing, and being able to do that in a way that doesn't carry with it this kind of constant self-worry and self-doubt about it being perfect or exceptional.

Speaker 4 And really, perfectionism is the thief of creativity in many ways. It stops us from putting things out there when they're not quite right because we worry about how that's going to be received.

Speaker 4 And I could tell you that firsthand from having written a book.

Speaker 4 You know, my editor, I think, was ready to throttle me at the end of the process because i was still tinkering iterating right to the end and it was so intensely difficult to get this one out and and atwood has almost the opposite perspective there seems to be a joy and an embrace of the process in her writing and that really comes through in her pages and it really comes through in a self-analysis of how she writes and why she writes and and the motivations behind it so i think she's a really good example actually of how you can be incredibly successful You can contribute so much to the world and not be a perfectionist.

Speaker 1 You know, we're talking about perfectionism mostly in a work context in this conversation, and that is perhaps where perfectionism mostly manifests itself.

Speaker 1

But it can also show up in the domestic sphere. There's a phrase you like: the good enough mother.

Tell me the story of Donald Winnicott.

Speaker 4 Donald Winnicott was was an English pediatrician and he wrote extensively on parenting in the 1950s and his idea of the good enough mother was something that was of a bombshell, I suppose, to mothers of the day who were holding themselves up to really impossible standards that were being placed on them in terms of the way they parent and the way they raise their children.

Speaker 4 And the idea of the good enough mother wasn't simply that perfect mothering or perfect parenting is not possible. Of course, it's not possible.

Speaker 4 But it was also that it's not even desirable for the mother themselves, but also for the child, because the child needs to learn about setbacks, difficulties, things not going quite to plan.

Speaker 4 And they need to know how to handle and deal with the frustrations and disappointments of those moments because the world is going to present those things to us all the time.

Speaker 4 And I think those were the key lessons that Winnicott really wanted to instill in mothers: that the good enough mother can help to raise children that are well-adjusted and happy and

Speaker 4 have a zest and purpose for life.

Speaker 1 You say there are steps that we can take as individuals to reduce the harmful effects of perfectionism.

Speaker 1 And one of the things that you've mentioned to me, Thomas, is that perfectionists tend to engage in a lot of rigid and unrealistic thinking. You know, they tell themselves, I must perform flawlessly.

Speaker 1 And if I don't perform flawlessly, everything around me is going to fall apart.

Speaker 1 You have a writing technique that you use for yourself and that you recommend to others that pushes back against this kind of thinking. What do you do?

Speaker 4 Yeah, so perfectionism indeed involves those really intrusive patterns of thinking.

Speaker 4 I must do this. I have to do that.

Speaker 4 Why can't you be this? Why can't you do that?

Speaker 4 And I think the most important thing to do when those feelings are starting to make themselves known to you is to write them down, think about them, reflect on them, and ask yourself, maybe on a scale of one to ten, how

Speaker 4 realistic is this? How achievable is this? And importantly, do I actually need to do this right now?

Speaker 4 What if I don't? What would happen? And again, often the consequences when we actually sit down and reflect are not as catastrophic as your perfectionism would have you think that they might be.

Speaker 1 You know, so often, Thomas, perfectionism is about seeing our work and our our accomplishments as extensions of ourselves. But of course, we don't have to do this.

Speaker 1 Instead of making ourselves the focus, we can make our work the focus. Now, you had a role model close to home who exemplified this idea of the work being its own reward.

Speaker 1 Tell me about your grandfather.

Speaker 4 My late grandfather was a master craftsman, and I used to watch him for hours as he would fashion everyday things like banisters, chairs, window frames in his workshop. And they were immaculate.

Speaker 4 From the vantage point of a child, they just seemed magical. You know, how on earth were you able to create these wonderful pieces of furniture?

Speaker 4 And of course, his meticulousness, his diligence, his conscientiousness, his high standards were unquestionably the traits of somebody who worked really hard and wanted to do things well, but they weren't the traits of a perfectionist.

Speaker 4 And, you know when i reflected on his way of striving versus mine it became evident to me really that the big difference was that when he had created the things that he created in his workshop he just took them to where they were going to live and left them there he didn't loiter for validation he didn't need that five-star review and as far as he was concerned they just needed to exist way more than he needed to be loved or recognized or appreciated.

Speaker 4

And that is the thing about high standards, I think. They really don't have to come with insecurity.

Only perfectionism grafts the two together.

Speaker 4 And that's why perfectionism isn't about perfecting things or tasks.

Speaker 4 It's about perfecting our imperfect selves and going through life trying to conceal every lash, blemish and shortcoming from those around us.

Speaker 4 So whenever I'm back home, I visit the places where my grandfather's carpentry is still installed because all those banisters and stairs and window frames that he brought into the world are really evidence of a man who had a vocation way bigger than himself.

Speaker 4 And of course, none of those things bear his name, but they're used and enjoyed by hundreds of people every single day.

Speaker 4 And I think just knowing that gave him an incredible sense of pride and accomplishment. And that's a wonderful way to live, and one in which I'm hoping in myself that I can also find that.

Speaker 1 Thomas Curran is a psychologist at the London School of Economics. He is the author of The Perfection Trap, Embracing the Power of Good Enough.

Speaker 1 Thomas, thank you so much for joining me today on Hidden Brain.

Speaker 4 Thank you for having me.

Speaker 1 If you like today's episode on perfectionism, please consider sharing it with one or two people in your life who could benefit from it. You know who they are.

Speaker 1 When we come back, your questions answered.

Speaker 1 Sociologist Alison Pugh returns to the show to answer listener questions about connective labor and why feeling seen by other people is so powerful and underappreciated.

Speaker 1 You're listening to Hidden Brain. I'm Shankar Vedanta.

Speaker 13 I'm gonna put you on, nephew.

Speaker 4 All right, um.

Speaker 14 Welcome to McDonald's. Can I take your order?

Speaker 16 Miss, I've been hitting up McDonald's for years.

Speaker 17 Now it's back.

Speaker 18 We need snack wraps.

Speaker 8 What's a snack wrap?

Speaker 13 It's the return of something great.

Speaker 3 Snack wrap is back.

Speaker 19 The growing demand for content means more chances for off-brand work getting out there. Adobe Express can help.

Speaker 19 It's the quick and easy app that gives your HR, sales, and marketing teams the power to create on-brand content at scale. Ensure everyone follows design guidelines with brand kits and lock templates.

Speaker 19 Give them the confidence to create with Firefly generative AI that's safe for business. And make sure your brand is protected, looks sharp, and shows up consistently in the wild.

Speaker 19 Learn more at adobe.com slash go slash express.

Speaker 1 This is Hidden Brain. I'm Shankar Vedanta.

Speaker 1 Have you ever been to a doctor's office and felt your physician was not really paying attention to you?

Speaker 1 Or maybe a time when a teacher seemed more interested in her computer than in you, the student sitting before her?

Speaker 1 You've certainly had a meal with someone and noticed them drop out of the conversation to check their phone.

Speaker 1 Why do we experience these moments so keenly? And are we aware when we are not fully present for others? What is the cost of such social disconnection?

Speaker 1 At Johns Hopkins University, sociologist Allison Pugh studies how we relate to one another. She's the author of The Last Human Job, The Work of Connecting in a Disconnected World.

Speaker 1 In this edition of Your Questions Answered, we've asked Allison to return to the show to answer your questions about connection.

Speaker 1 If you missed our earlier episodes with Allison, you can find them in this podcast feed. The first is called Relationships 2.0, The Price of Disconnection.

Speaker 1 And the second, available to Hidden Brain Plus subscribers, is called Relationships 2.0, Recovering the Human Touch.

Speaker 1 In that first conversation, Allison told me a story about growing up as the youngest of five children in her family.

Speaker 1 When she was about three years old, her family moved to New York City, and her parents had to find schools for all the children to attend.

Speaker 6

Yeah, so my father was busy at work and my mother was kind of in charge of figuring out what schools the kids would go to. And she solved the problem for my oldest brother.

And he was, I think, 14.

Speaker 6 And then my sister, then my brother, then my sister.

Speaker 6 And then, you know, I think somewhere around August, she looks down and she sees me and was like, wait a minute, I don't have a place for you to go. So, you know, I think she, you know,

Speaker 6 made some last-minute arrangement that got me into a preschool.

Speaker 1 Allison laughs about the moment now, but she did notice that her mom had basically ignored her.

Speaker 1 In our second conversation, she recalled another moment, this time as a grown-up, when she felt unseen, or at least misseen.

Speaker 1 She was working in the Foreign Service, and a senior diplomat made an assumption about her.

Speaker 6 My familial background involves I have, you know, some Irish in me, and a big portion of my identity is Italian. And

Speaker 6 my family has recipes for lasagna and red sauce and calamari and stuffed peppers. And, you know, like I am an Italian-raised cook.

Speaker 6 And so when I was about 24 or 25, I was in Honduras as a foreign service officer. And my,

Speaker 6 in, in Honduras, they have, the garlic they sell is unusually small.

Speaker 6 The cloves are really tiny. And I remember my ambassador kind of joking about how hard it was to cook with these tiny little.

Speaker 6 And then he's looking at me and he goes, what do you know, you know, about, why why am i talking to you about this you're just some wasp you don't know anything about garlic and i was just taken aback by the misread like he had no idea you know i might look like a wasp on the outside that's my father's background but you know he had no idea that you know my great-grandmother was a contract bride from southern italy you know she was not literate and he saw this external self and not not this part that you know is actually a big part of my identity so that was a a misread, I would say.

Speaker 1 So when he sees you as a white Anglo-Saxon Protestant, but in fact, that doesn't align with how you see yourself, how did that change your relationship with him?

Speaker 1 And how did it change how you experienced that moment, Alison?

Speaker 6 Yeah, I mean,

Speaker 6 it was a kind of jarring moment,

Speaker 6 but I did still know he was a nice guy.

Speaker 6 There was nothing pernicious about it, but there was, it did make us a little more distant, you know, or it did make me see, it helped me understand how little he knew who he was talking to.

Speaker 1 Alison, one of the primary ideas we talked about in our previous conversations is what you call connective labor. What is connective labor?

Speaker 6 So connective labor is the work of seeing the other person and having the other person feel seen.

Speaker 1 And it's all the work that that requires from reflective listening to kind of adjusting what you're saying given what they're how they're responding it's an interactive dance and the interactive part is very important hmm now I can think of professions like a psychotherapist or a or a chaplain at a hospital where I can imagine these skills are really really vital but you are saying It's not just in these professions which call for hearing and listening that these skills are important.

Speaker 1 You're saying these are important skills more generally, right?

Speaker 6 Yes, exactly. They

Speaker 6 underlie so many occupations from therapy, you know, teaching, primary care, but also, you know, your hairdresser, your real estate agent, your soccer coach,

Speaker 6

the lawyer. You know, there's the manager for sure.

high-end sales.

Speaker 6 There's many, many people who use this kind of connective labor

Speaker 6 to achieve the outcomes for which they're getting paid.

Speaker 1 You know, we've all had the experience of, you know, having, you know, like a contractor or

Speaker 1 someone who's providing some service come to your home, and the person either listens to you carefully or doesn't listen to you carefully.

Speaker 1 And it's an example of connective labor in a place where you wouldn't think it matters at all.

Speaker 6 Exactly. I mean, those are really great examples.

Speaker 6 You know, the fact that we associate this kind of work with only very particular, very kind of feeling professions means we're really underestimating its prevalence and its importance.

Speaker 6

And also, may I say, it's kind of gendered. We're misunderstanding it as only the province of women.

When men do it, we ignore it.

Speaker 6 So it's gender, you know, how we respond to it is gendered, but I think it happens all over the economy.

Speaker 1 Aaron Powell, can you talk a moment about the effects of connective labor? So you mentioned, for example, the salesperson who is selling you a car or a refrigerator.

Speaker 1 Talk about the effect of actually forming a connection with your customer when you're trying to sell something to him or her.

Speaker 6 Well, for sales in particular, I mean, actually, this is happening in many different occupations. To be seen by another human being

Speaker 6

is, you know, has some profound effects. There's a ton of research that talks about that for teaching and for therapy and for medicine.

But even in sales,

Speaker 6 you know, salespeople know this.

Speaker 6 When you, the salesperson, effectively identify somebody's problems or, you know, their perspective, it is much more persuasive.

Speaker 6 It's very powerful to be seen by another human being, even when that's just for persuasion.

Speaker 1 Yeah. And I've had conversations with salespeople who are very skilled.

Speaker 1 And even when I know that they're just trying to manipulate me, or even if I know that they're just, you know, going through the motions, it does make me feel great when they basically feel like they have understood why I need this particular device or why I need this particular service.

Speaker 6 Yes, the feeling of being understood is a powerful one. And the feeling of being misunderstood or feeling invisible or misrecognized, that is kind of equally powerful in a negative sense.

Speaker 1 So, this brings us to a question from a listener named Francis about cross-cultural communication. And you could argue in some ways that all communication is cross-cultural communication.

Speaker 1 We're always communicating across cultural divides. But when we're conversing with someone from a different background, does that make the job of connective labor even more difficult?

Speaker 6 That's a super important question.

Speaker 6 Given that we don't know the other person, even when we think they do, it's not a terrible approach to kind of start with humility.

Speaker 6 So even it's perhaps easier when you know they're from a different culture or background or race or whatever. But

Speaker 6 we should all, I think this starts with humility. And actually, there's been great psychological research talking about how

Speaker 6 we shouldn't think of this as perspective taking. We should instead think of this as perspective getting.

Speaker 6

So it starts with asking or checking on your assumptions about them. So your posture towards reading them is not like, this is what you're feeling.

It's, it's, so it sounds like something like this.

Speaker 6 You know, it's a, it's more tentative and you're, you're aware.

Speaker 6 Your first task is to listen and

Speaker 6 to be humble. And that's, that's, those sounds simple, but actually when, you know, so much of our misreads happen under conditions of trying to do it quickly.

Speaker 6 So many of the practitioners in these, in these fields, like start with, let's start with primary care physicians, you know, have like no time.

Speaker 6 So I have a lot of sympathy for the working conditions that are making it hard for them to see other people, but I would say try and hold that off because your efficiency pressures are going to make you do this poorly.

Speaker 1 I'm wondering if there is some tension here, which is that when we know we're interacting with someone who comes from a very different background than ours, I think, you know, you might call it humility.

Speaker 1 I might call it tentativeness, which is we are a little cautious in terms of what we say and what we do. We're afraid of giving offense.

Speaker 1 We don't want the other person to misunderstand what we're saying. But I'm wondering if all of that walking on eggshells actually makes the job of connective labor more difficult.

Speaker 1 Because, of course, you're not connecting fully, you're not jumping into the conversation fully, you're sort of walking very tentatively. Is there a tension between these two things of

Speaker 1 trying to be very humble and be cautious about what you're doing, and also trying to reach forward and make a deep connection with someone else?

Speaker 6 Hmm, that's interesting.

Speaker 6

I'm not sure. When I'm saying tentative, I'm not saying don't do it.

So don't take the risk of

Speaker 6 saying what you think they're saying to you.

Speaker 6 But just be aware that you might be wrong and be open to that and being like, and correcting that.

Speaker 6 There's a lot of research that shows that when you correct something that's wrong, they feel more seen.

Speaker 6 But really, it's the task of listening and taking a risk.

Speaker 6 I gave a talk in Oregon recently and someone was telling me about how they had had a horseback riding accident and they almost couldn't walk as a result, but then they managed to, you know, now they are walking, are able to run, et cetera.

Speaker 6 But she talked about how her feelings about her body, she's become much more cautious and wary and uncertain about what her body can do. And listening to her, I said, it's like a loss of innocence.

Speaker 6 Like before she was innocent about and just taking risks because it was fun and she could do it and whatever. And now she no longer believes that about herself.

Speaker 6 And her response to the, it's a loss of this innocence was like, when you do connective labor well, it's like powerful relief, a great sense of affinity.

Speaker 6 You know, like really, we were really bonded in that 30-second interaction. And

Speaker 6 to me,

Speaker 6

to me, that felt like take a risk. You know, like what she was saying to me, I was just saying back to her.

And so I wasn't tentative, but I was certainly open to the fact that I could be wrong.

Speaker 6 So yeah, I guess the tension is you have to take that step, you have to

Speaker 6 take that risk, but also be very correctable.

Speaker 1 Sometimes the emotional connections we are called upon to make involve delicate social relationships with strangers.

Speaker 1 Marsha had a question about emotional connection, but I think at some level, it's also a moral question. Here she is.

Speaker 20 I go into Philadelphia once in a while to visit my friend, and I will often pass by homeless people on the sidewalk or leaning against a building.

Speaker 20 I'm uncomfortable just passing by without making any eye contact, but I also

Speaker 20 often am not in any position to give them any kind of a donation or help.

Speaker 20 It seems rude to walk by, and yet I'm not sure how it would feel to look them in the eye or acknowledge them and then continue to walk on.

Speaker 20 What's the best way to handle this kind of a situation?

Speaker 1

So I don't think this is an easy question at all, Alison. I think it's an everyday kind of occurrence, but I think at some level it's a profound question.

What do you think?

Speaker 6

I agree it's a profound question. I also agree it is an everyday one, especially for those of us who live in urban environments.

And it's not just about the unhoused. It's also about just

Speaker 6 seeing people in our midst who have deep need that you can't meet.

Speaker 6 Just speaking directly to this questioner, I would say in my experience, they really appreciate

Speaker 6

your acknowledgement. I think the worst is when you don't acknowledge them at all.

So

Speaker 6 you know, just looking in them in the eye and saying, you know, I can't help you today, but I hope you have a good day or something, you know, something that acknowledges them as a human being is, you know, one way forward.

Speaker 6 In terms of like, kind of the broader question of like, how do we handle interactions with those who are coming to us with much greater need than we can meet?

Speaker 6 And I heard this again and again from

Speaker 6 people I talked to because

Speaker 6 the people who do this work are often on the front line of, you know, societal need that some of us might be more protected from.

Speaker 6 So I'm talking about like bus drivers or librarians or social workers or community police. These are people who are like right on the edge.

Speaker 6 Again and again, they told me how desperate it felt out there.

Speaker 6 They feel incompetent or helpless or,

Speaker 6 you know, kind of overwhelmed. And that can be really daunting.

Speaker 6 We have to kind of recognize that many people are feeling not just

Speaker 6 the pernicious effect of inequality and all these unhoused, but also many people are feeling really invisible. They feel like a number.

Speaker 6 They're being kind of processed in standardized ways all day, every day.

Speaker 6 And

Speaker 6 the sense of invisibility is creating

Speaker 6 really a depersonalization crisis. And you're not going to be able to solve that completely.

Speaker 6 But

Speaker 6 you are going to be able to see them for a moment. And I do think it makes a difference.

Speaker 6 There's a lot of research that suggests these kind of minor interactions that we might dismiss actually make a difference.

Speaker 1

When we come back, more questions about social disconnection and connective labor. You're listening to Hidden Brain.

I'm Shankar Vedanta.

Speaker 13 I'm going to put you on, nephew.

Speaker 4 All right, um.

Speaker 14 Welcome to McDonald's. Can I take your order?

Speaker 16 Miss, I've been hitting up McDonald's for years.

Speaker 17 Now it's back.

Speaker 18 We need snack wraps.

Speaker 13 What's a snack rap? It's the return of something great.

Speaker 3 SnackRap is back.

Speaker 19 The growing demand for content means more chances for off-brand work getting out there. Adobe Express can help.

Speaker 19 It's the quick and easy app that gives your HR, sales, and marketing teams the power to create on-brand content at scale. Ensure everyone follows design guidelines with brand kits and lock templates.

Speaker 19 Give them the confidence to create with Firefly generative AI that's safe for business. And make sure your brand is protected, looks sharp, and shows up consistently in the wild.

Speaker 19 Learn more at adobe.com slash go slash express.

Speaker 1 This is Hidden Brain. I'm Shankar Vedantam.

Speaker 1 Sociologist Alison Pugh studies how we relate to one another.

Speaker 1 She believes that an essential component of most jobs, perhaps the essential component of most jobs, is not technical skill or knowledge, but the ability to see and hear other people, to be present for them, to give them attention.

Speaker 1

Allison, you have a lovely example of a moment when you are on the receiving end of connective labor. You had a mentor in grad school at UC Berkeley who did this for you.

Tell me that story.

Speaker 6 Sure.

Speaker 6 Yeah,

Speaker 6 I am grateful to be mentored by Arlie Hoaxhield. She's a sociologist of great renown who is actually a really

Speaker 6 tremendous, kind of the quintessential connective labor.

Speaker 6 So when I was in graduate school, I

Speaker 6 came upon, I thought of an idea for a dissertation that captured my interest in the conflict between work and family. And that was a sociology of sleep.

Speaker 6 And so I did some interviews and my advisors, including Arlie, were extremely excited about it. They saw it as original, unique, no one's talking about this.

Speaker 6 And I can see now, like in retrospect, that they are right. It was a, you know, kind of unconventional and good idea.

Speaker 6 But I lost interest in it and I decided not to do it.

Speaker 6 And instead, I embarked on a study of consumer culture and how much we spend on kids and how that varies by class and race and the meaning of stuff to kids. And it went fine.

Speaker 6 But there was some disappointment, I think, among my advisors for something that was probably a little more conventional, a subject.

Speaker 6 and at the same time Arlie was not like no you can't do that she just kind of was trying to coax my song out of me and that's the the PhD advisor's task and I felt

Speaker 6 not only did she give me permission or you know not only was I able to do this I just felt throughout you know our decades-long relationship now

Speaker 6 her capacity to read and reflect what I was giving off to her. And that really is

Speaker 6 profoundly moving and also empowering on some level. So, yeah, it's a blessing to have someone like that in your life.

Speaker 1 I mean, I'm thinking that this is part of the role that parents play in the role of children, where you're trying to say, I want you to sing your song.

Speaker 1 And it's difficult, partly because parents also have a view of the song that their children need to sing and the songs that their children are good at singing.

Speaker 1 And so, in some ways, it requires you to hold back your own views of what the other person should be thinking, should be doing, and allow the other person to basically shine forth.

Speaker 6 That's so well put. Parents shouldn't be saying, I want you to sing my song.

Speaker 6

Parents should be saying, I want you to sing your song. You know your kids so well.

It's very tempting to be like, this is what I see, and I am right.

Speaker 6 They have to make their way. And

Speaker 6 yeah, that's the restraint that that requires among those of us who have maybe studied our children all their lives

Speaker 6 is

Speaker 6 considerable.

Speaker 1 So in our initial conversation, we talked about the benefits that patients experience when their doctors take the time to connect with them.

Speaker 1 A listener named Molly wrote to us with a question about how connective labor affects the person making the effort, the connective laborer, if you will.

Speaker 1 Molly is a school therapist and feels she provides a lot of connective labor to others, but feels she receives very little in return.

Speaker 1 She writes, I think this leads to cultures of venting and burnout when you provide this connection for others but have nowhere to seek it yourself.

Speaker 1 What are your thoughts on how to better support people providing emotional connection as part of their professional responsibilities?

Speaker 6 I mean, I hear the pain in that question,

Speaker 6 and I would say it's widely shared. One of the reasons why I wrote the book I wrote was to give people a vocabulary to be able to assert their needs as connective labor practitioners.

Speaker 6 Because what I found is that too often we are relying on people as individual heroes. And instead, there's a social architecture that organizations put into place that support it or impede it.

Speaker 6 And it sounds like this writer is working in a context in which her labor is being kind of

Speaker 6

taken for granted and perhaps even impeded. by her organization.

And that actually is a tragedy. You know, I ended up finding a set of factors that

Speaker 6 contribute to kind of a good social architecture where

Speaker 6 what kind of organizations are doing it right. And

Speaker 6 one of the key factors is are there other people to talk to who do this? I ended up calling that a sounding board. And are there sounding boards out there? And this is

Speaker 6 something that therapists know, teachers know, you know, like they have those,

Speaker 6 that's a kind of common practice to to have a group of people who are, you know, I had one teacher who was, he was like the math family, you know, the people who teach math, that's who I'm talking to about problems.

Speaker 6 Or therapists have a kind of very extensive,

Speaker 6 you know, supervision, but also, you know, kind of consultative practice with other therapists where they can talk about what they're experiencing or finding or processing.

Speaker 6 Those are, those are crucial.

Speaker 6 I want to say one other thing about the

Speaker 6 kind of what I'm hearing underneath that emails

Speaker 6 lament, and that is about burnout.

Speaker 6 A lot of the treatment for burnout is,

Speaker 6

you know, take a day off, take a vacation, make sure you take your lunch, you know, practice mindfulness. It's very individual.

And

Speaker 6

it also kind of all subscribes. to the theory that it's too much relationship is causing burnout.

There's too many people

Speaker 6 kind of sucking you dry. And I actually think that that's a misread because so many people talk to me about how sustaining they find

Speaker 6 these relationships. So I started to think like we're running around with a metaphor of workers as like kind of these buckets of compassion that spring holes from which their compassion drains away.

Speaker 6 And actually,

Speaker 6 I don't think that's the right metaphor. I think we should think about like kind of the workers are as soil and the relationships as rain.

Speaker 6 And sometimes the rain is torrential or toxic and sometimes the soil is too dry.

Speaker 6 But it's not that we don't need rain. It's that we need the working conditions that enable the rain to be restorative.

Speaker 1 I'm wondering in in Molly's case, where she basically says she's providing this service to others but feels she doesn't receive a lot of it herself, some of it, in fact, might be what her organization can do, maybe provide these sounding boards, encourage people to find these sounding boards.

Speaker 1 But I'm also hearing, in some ways, from Molly's own perspective, maybe she should go looking for sounding boards. She should actually try and develop a network of people who can be sounding boards.