Murder Mystery

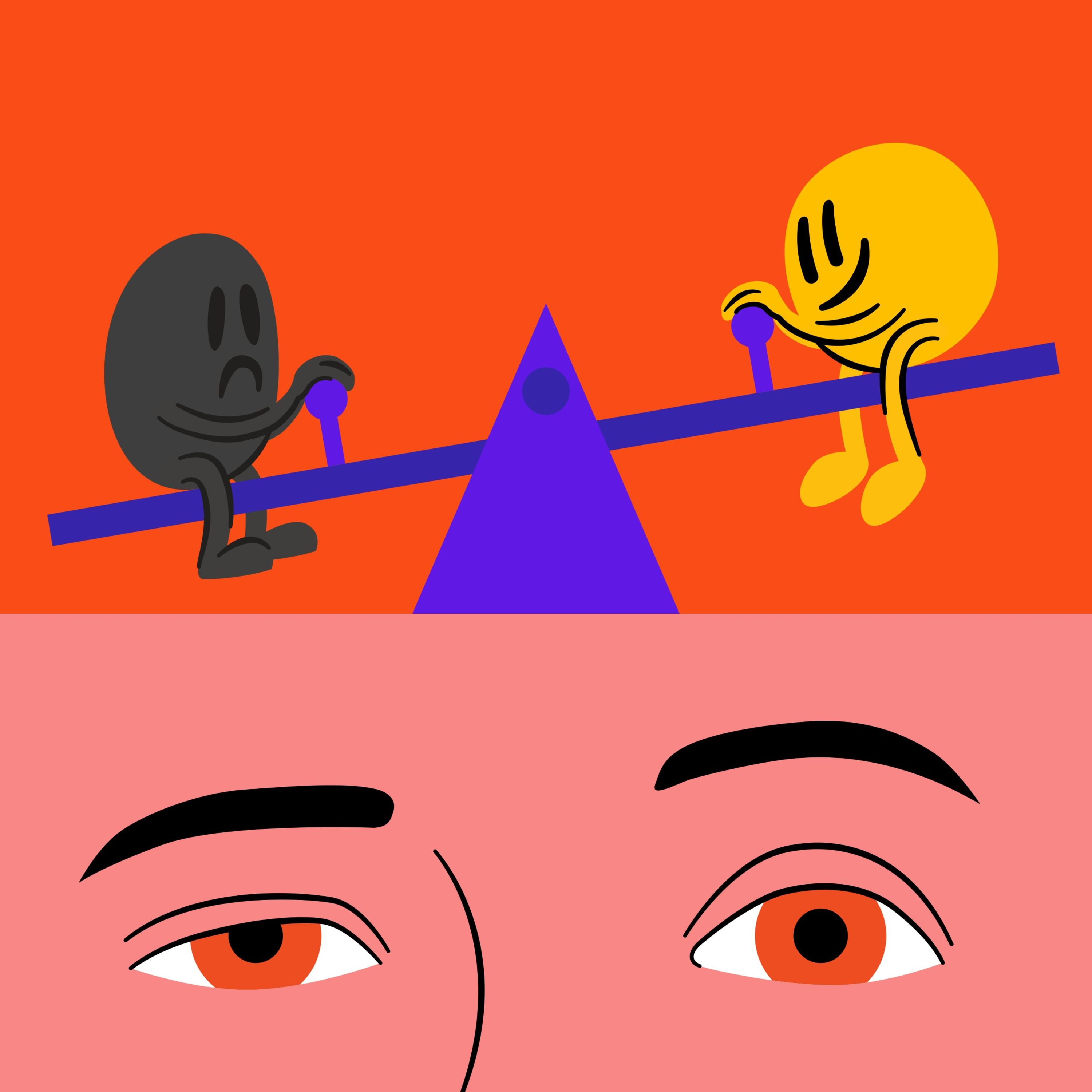

Why are so many of us drawn to horror, gore, and true crime? Why do we crane our necks to see the scene of a crash on the highway? Psychologist Coltan Scrivner says that our natural morbid curiosity serves a purpose. We talk with Coltan about our fascination with tales of murder and mayhem, and what this tendency reveals about our minds.

Press play and read along

Transcript

Transcript is processing—check back soon.

Hidden Brain — Murder Mystery