Trump v. Tylenol. Plus, How Charlie Kirk Became a Martyr for the Christian Right.

Press play and read along

Transcript

Speaker 1 Taking Tylenol is

Speaker 2 not good.

Speaker 3 This week, Trump claimed without evidence that autism is linked to acetaminophen use during pregnancy. As research budgets are slashed, brace for more bad science to come.

Speaker 3 From WNYC in New York, this is on the media. I'm Brooke Gladstone.

Speaker 4 And I'm Michael Loewinger. Also on this week's show, What Happens When the War on Drugs Combines with the War on Terror?

Speaker 5 The line that's been coming out of the administration is that drugs are a serious national security threat to the United States, and that therefore anyone bringing drugs into the U.S.

Speaker 5 is a legitimate target.

Speaker 3 Plus, at Charlie Kirk's funeral, we saw how a certain strand of Christianity has become enmeshed with the Trump administration's goals.

Speaker 8 For Charlie, we must remember that he is a hero to the United States of America and he is a martyr for the Christian faith.

Speaker 4 It's all coming up after this.

Speaker 4 From WNYC in New York, this is on the media. I'm Michael Loewinger.

Speaker 3 And I'm Brooke Gladstone. First, a quick follow-up on last week's big health scare slash news.

Speaker 1 Taking Tylenol

Speaker 1 is

Speaker 1 not good.

Speaker 3 Trump says there may be a link between autism and acetaminophen use during pregnancy. Or, much more likely, maybe not.

Speaker 3 He drew on evidence that, as the Washington Post put it, is unsettled, disputed, and failed to pass legal scrutiny in U.S. District Court in New York.

Speaker 3 So, parents desperate for answers will have to make do with bread and circuses, like Trump's currently baseless warning about Tylenol, which follows a promise that Health Secretary Robert F.

Speaker 3 Kennedy made back in April.

Speaker 5 By September, we will know what has caused the autism epidemic.

Speaker 9 And we're going to announce a series of new studies

Speaker 9 to identify precisely what the environmental toxins are that are causing it. This has not been done before.

Speaker 10

It's so frustrating. We have been doing that research.

I had been doing that research for 20 years.

Speaker 3 Erin McCandless, then a research epidemiologist at the CDC and the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health, heard RFK Jr.

Speaker 3 say that on the radio just as she was finishing up a study on the links between environmental pollution and autism.

Speaker 5 Who knew?

Speaker 10 These programs now have no idea about the science. There is a lot of environmental exposures associated with autism.

Speaker 10 These are things that consistently come up: air pollution, metal exposures, pesticides, PFAS, and PFAS, solvents, xylene paint, varnishes, finishes.

Speaker 3 Around the time that RFK Jr. killed her entire division at the CDC, he allocated $50 million to his new, quote, autism data science initiative.

Speaker 10 We had just received our longitudinal data for this project that we had been working on for 20 years.

Speaker 10 Everybody in my building, except some of the commissioned corps officers and contract employees, everybody had been fired.

Speaker 10 It's really sad and it's upsetting because here's somebody saying, oh, we haven't done this. We need to go back and do this.

Speaker 10 No, what we need to do is take the work that we've done and keep moving forward with it.

Speaker 3 But autism research at the CDC is just one area of medical research trampled by MAGA's march to the sea against expertise.

Speaker 11 The National Institutes of Health abruptly announced it will make cuts to biomedical research funding.

Speaker 12 It has fired over 1,300 employees and canceled more than $2 billion in federal research funds.

Speaker 14 Some of those funding cuts affected research that explored race and gender identity. The judge ordered the grants restored.

Speaker 3 John Tuttill is a neurobiology and biophysics professor at the University of Washington and a grant reviewer at the NIH.

Speaker 2 John, welcome to the show.

Speaker 15 Thank you.

Speaker 3 You're speaking to us from an hour-long break during what you call the study section for the NIH. What is that?

Speaker 15 So a group of about 30 scientists, faculty from all over the U.S., evaluate proposals from other scientists.

Speaker 15 We get together several times a year after having read in detail, in this case, it's about 90 grants that people submitted.

Speaker 15 Each of of us reads about 10 grants, and we submit our reviews, and then a few days later, after having read each other's reviews, we get together on Zoom for two 12-hour days and hammer out our reviews and score all of the grants.

Speaker 3 The NIH, when it's operating properly, does this every single year, right?

Speaker 15 Yeah, it's happening constantly. On any given day, there's almost certainly a study section happening on some topic.

Speaker 15 And the topic that my study section is specifically focused on is sensory motor neuroscience. So like how the brain controls the body, senses the body, things like that.

Speaker 3 How does it work when it's not operating properly?

Speaker 15 Well, I think the first preview of how it shouldn't work came last February when all study sections were paused. Each study section needs to be posted on what's called the Federal Register.

Speaker 15 And so they managed to block all study sections from meeting by just not posting them on the Federal Register to just halt the whole system.

Speaker 15

And right now, it's actually back to a point where it feels relatively normal. We're meeting again, but fewer grants are getting funded.

Some grants are arbitrarily being chosen not to get funded.

Speaker 15 It's very opaque how our reviews end up getting translated into actual funding of science.

Speaker 15 In the past, those decisions were made by scientists and administrators at the NIH in a way that was fair and integrated our input on the quality of applications and the quality of the science in an informed way to pick what grants get funded.

Speaker 15 But now it's changed that the administration is using whatever levers they're capable of using to influence which grants are getting funded.

Speaker 15 That power kind of existed before, but like many of the executive powers, these things hadn't been leveraged in the same way to override what the scientific evaluators like us would opt to have funded.

Speaker 3 So I'm wondering how these new conditions influenced you and your fellow reviewers in how you rank these applications. I mean, over the next couple of days, you'll be discussing more than 90 grants.

Speaker 15 My experience is that probably about a third to half of the grants I read, this is really amazing science and should be done.

Speaker 15 But we know that among these 90 grants we're evaluating, only a very small number will potentially get funded because the funding rates have dropped so much. going forward into the next fiscal year.

Speaker 15 Right now, we're still operating on the funding from last year, and they're still managing to kind of gum up the works.

Speaker 15 Everybody's kind of getting 15 or 20% cuts on grants that are the next year of a grant you already have.

Speaker 15 And so it's really tough when you're evaluating grants in the back of your mind to know that only five or less than 10% of the grants will get funded.

Speaker 15 It's not something I used to think about that much. It used to be for neuroscience, 20% of the grants we evaluated would get funded.

Speaker 15 I mean, we prefer to have it be 30 or 40%, like it is some other countries.

Speaker 15 But when it's so low, you can't help but think about how so much of the work we're doing is not going to result in the science actually getting done.

Speaker 3 From what I understand, though, the Trump administration threatened the 40% budget cut for the NIH, but it's largely walked it back after a court order. Shouldn't the money be flowing into NIH again?

Speaker 2 In the past week, we've seen a lot of grants funded, but the rate of funding is much lower than it has been in the past. And so why is that?

Speaker 2 One thing could be that the Doge cuts to the administrative staff and the NIH has made it really hard to just do the administrative work you need to do to fund the grants.

Speaker 2 Another possibility is that grants are being withheld because they're flagged for some reason. Programs could be getting canceled, and so they're not funding any grants under this particular program.

Speaker 2 It's kind of hard to know. People are getting scores back in the top two,

Speaker 2

top 5% of all the science that has been submitted, the reviewers are saying, this is amazing. Like this is going to be transformational.

And those proposals aren't getting funded.

Speaker 3 You wrote that, quote, as much harm as a 40% cut to the NIH budget would have on scientific innovation, destroying the peer evaluation system that decides what science is funded would be far worse.

Speaker 3 Why worse?

Speaker 2 Well, I think there's two things. One is that The system we've built up for how we choose what science to do is one of the key reasons why U.S.

Speaker 2 science has led scientific innovation all over the world.

Speaker 2 It's extremely laborious, but the best way to get effective groundbreaking science done is to have other scientists decide this is the work that is the most innovative.

Speaker 2 And yes, you do want people that are able to think outside the box, and there are mechanisms within the review system that allow for that.

Speaker 2 And destroying that system would, first of all, I think decrease the quality of science that's being done. And secondly, there is immense potential for waste.

Speaker 2 So once you start funding poor quality science, that funding is both being taken away from folks who are doing actual really rigorous work.

Speaker 2 And then it is going to, and it's unclear to me who would be doing this work.

Speaker 2 But when you see the President of the United States going out and making completely unfounded claims about the relationship between Tylenol and autism, when we as a country are leading the research into the underlying cause of autism, it makes you think, okay, well, if they're making this claim, then could they divert funding to actually support those claims?

Speaker 2 I mean, they said in the press conference that they're going to fund a bunch of new studies on these links. So who's going to do that work and how is it going to be done?

Speaker 3 As you mentioned, American science has been at the forefront of almost all major biomedical breakthroughs, at least in our lifetimes, more or less.

Speaker 3 So there was amazing news this week that the first gene therapy to cure Huntington's has worked.

Speaker 3 How did that wend its way through the NIH?

Speaker 2

Well, the seeds of that work were planted many decades ago by basic scientists who were studying in a purely curiosity-driven way. a tiny nematode, a microscopic worm called C.

elegans.

Speaker 2 People study it because it's so small and you can see how individual genes influence its development.

Speaker 2 And so there was a scientist who was just trying to solve this puzzle of how this particular sequence of DNA affected the development of the worm, which led to the discovery of these microRNAs, which were initially just fascinating that these exist,

Speaker 2 but then it was shown that they also exist in other animals. And eventually we realized like, oh, these are ubiquitous across all animals.

Speaker 2 And then somebody decided, oh, these microRNAs, we can actually use them to change gene expression. And then eventually that was applied to mammals and finally translated into humans.

Speaker 2 And this is an example of a clinical trial that takes a piece of fundamental knowledge figured out by a scientist just studying a little puzzle in their lab and then using it to cure disease.

Speaker 2 And it feels like when you see this kind of news, oh, scientists, they probably just rolled the dice and came up with a cure and that's how it happens.

Speaker 2 But it's really building up this tower of knowledge built on the foundation of studying basic biology of the type that's funded by the National Institute of Health and the NSF.

Speaker 3 And yet it's the kind of thing that if you say it in a congressional hearing, they'll say, why don't we need this study into worms?

Speaker 2

Totally. It is hard for people to understand.

I mean, I deal with this when I explain to my family what it is I do for work.

Speaker 2 When I summarize the research I'm doing, they're like, okay, well, how does that help? Or why are we funding this? And the reality is we don't know how this work is going to be useful.

Speaker 3 In your transmitter piece, you quoted White House Deputy Press Secretary Kush Desai, who said, quote, paying so-called experts to deliberate bad ideas for hundreds of hours is exactly the kind of waste that Doge is eliminating.

Speaker 3 So every year you spend cumulatively 100 to 200 hours reviewing between 35 and 80 grants, and you receive a total of $400 in compensation.

Speaker 3 You calculated that adjusting for inflation, this amounts to less than half the hourly wage that you earned as a 16-year-old dishwashing prodigy at the, quote, finest Mexican restaurant in central Maine.

Speaker 3 Do I have that right?

Speaker 2 Yes. Buena Petito, still the finest Mexican restaurant in central Maine.

Speaker 3 That said,

Speaker 3 why do it?

Speaker 2 I think like most people, I do it because I believe in what the NIH is funding and

Speaker 2

I feel a sense of duty to contribute to the process that has supported the funding of my lab. There are also benefits to doing it.

You learn a lot. You're reading people's best ideas.

Speaker 2

You're seeing how other people talk about science. It makes you a better grant writer.

It makes you a better scientist.

Speaker 2 But fundamentally, the reason I do it is because I feel like I'm part of this system that is working, that is producing scientific innovation, is leading to scientific breakthroughs.

Speaker 2 And it's my responsibility as a scientist who has benefited from that system to give back to it.

Speaker 3 Aaron Powell, what's in it for the Trump administration to try and dismantle the single largest funder of biomedical sciences in the world? Why the sciences anyway?

Speaker 2

Well, this is very much outside my expertise. But there is clearly a war happening on expertise across the government.

And we are, in some ways, the epitome of expertise.

Speaker 2 We claim to have some authority and knowledge about how biological systems are working that is more valuable than the average person on the street.

Speaker 2 I just think that is something that the Trump administration generally seems to view not as a positive. That kind of expertise is being drained from our government generally.

Speaker 2 And the NIH is a bunch of pinheaded experts, scientists like me.

Speaker 2 We study these really niche topics and become experts on them and then hope that someday somebody calls us up and asks how like a fruit fly's brain keeps track of where its body is, which is the research I do.

Speaker 2 But for the most part, we're just working on our little puzzles in our lab and hoping that someday it has some benefit for the world.

Speaker 2 And in that way, you develop expertise and that kind of expertise is no longer welcome.

Speaker 3 John, I know you have to run and rejoin your cadre of overpaid pinheads to review more grants. So thank you very much.

Speaker 2 All right, thanks, Brooke.

Speaker 3 John Tuttill is a professor of neurobiology and biophysics at the University of Washington and a grant reviewer for the National Institutes of Health.

Speaker 4 Coming up, what happens when the war on drugs meets the war on terror?

Speaker 3 This is on the media.

Speaker 5 When I go up.

Speaker 13 You are closing that valve, pushing the air

Speaker 5 through this closed valve.

Speaker 13 Asserting dominance, showing affection, wooing mates, communicating thoughts, ideas, feelings, emotions, and all of it is distinct to you.

Speaker 5 It's the voice. The voice.

Speaker 16 La voi.

Speaker 4 Voice on Radio Lab. Get it wherever you get podcasts.

Speaker 3 This is on the media. I'm Brooke Gladstone.

Speaker 4 And I'm Michael Loewinger. Another week, another shooting.

Speaker 17

Right now, law enforcement is investigating a deadly shooting at an immigration facility in Dallas. We know one person was killed and two others injured.

All three had been detained by ICE.

Speaker 4 Within hours of the attack, the administration began to seed its narrative.

Speaker 4 FBI Director Cash Patel posted on X a picture of shell casings allegedly belonging to the shooter featuring the words anti-ICE in all caps, written in what looks like a blue marker.

Speaker 18 Luce notes included a game plan of the attack. He wrote that he intended to maximize lethality against ICE personnel and to maximize property damage at the facility.

Speaker 4 For what it's worth, the suspect's family told the New York Post that they didn't think he was anti-ICE and that he wasn't a radical leftist.

Speaker 4 Estranged friends of the alleged shooter told journalist Ken Klippenstein that he was an edgelord with vaguely libertarian politics, a guy who hated both parties and spent a lot of time on 4chan.

Speaker 4 On Thursday, with the attack as pretext, Trump signed a presidential memorandum outlining a broad plan to use law enforcement and the IRS to target NGOs, funders, and other groups that supposedly incite violence by espousing, quote, anti-Americanism, anti-capitalism, and anti-Christianity.

Speaker 19 And thanks to your recognition of this and this executive order and the AG's leadership to lead out and prosecute these individuals, we are properly going to chase them down like the domestic terrorists that they are.

Speaker 4 Terrorism is the word we're hearing more and more these days from the president and his followers. To describe an imaginary web of groups somehow responsible for Charlie Kirk's death.

Speaker 4 To describe the activities of liberal billionaire George Soros and his open society foundations. And to describe anti-fascist activism.

Speaker 20 Posting on social media, I am pleased to inform our many USA patriots that I am designating Antifa a sick, dangerous radical left disaster as a major terrorist organization.

Speaker 4 To be clear, there are no laws on the books that allow the president to designate domestic terrorism organizations, nor is Antifa a group.

Speaker 4 No dues-paying members, no official chapters or central leadership, just another scapegoat, kind of like trans people.

Speaker 21

We have been on this for years. We have called for the FBI to designate it as a domestic terrorism event.

Out at what happened with Charlie Kirk.

Speaker 4 Mike Howell of the Heritage Foundation last week on his podcast repeated the lie that trans people were responsible for Kirk's death.

Speaker 4 In general, mass violence perpetrated by trans people is very rare, especially compared to cisgender men.

Speaker 4 And yet, Howell, an architect of Project 2025, has been lobbying the FBI to adopt a new terrorist category, T-I-V-E.

Speaker 21 Transgender-inspired ideology, you know, violence and extremism. This is a predictable predictable type of domestic terrorism from a predictable source that is incubated, that is built on violence.

Speaker 4 If combating extremism is a genuine priority for this administration, then why did they fire all those prosecutors and FBI agents who worked on the January 6th cases?

Speaker 4 Why did they appoint Thomas Fugate as the head of the extremism division at the Department of Homeland Security?

Speaker 11 He's 22 years old, one year out of college with no evident national security experience whatsoever.

Speaker 11 Before volunteering for the Trump campaign, his LinkedIn page reportedly explains that his work experience includes, quote, lawn care work around my neighborhood.

Speaker 11 According to ProPublica, quote, the bulk of his leadership experience comes from having served as secretary general of a model United Nations club in school.

Speaker 4 Then there's another terrorism story happening right now outside our borders in the Caribbean Sea.

Speaker 12 The U.S.

Speaker 1 attacked a boat allegedly carrying illegal drugs from Venezuela, killing 11 people on board.

Speaker 17 President Trump released this video of what is apparently a second strike against a Venezuelan boat that he says was carrying drugs to the U.S.

Speaker 11 President Trump says the U.S. has now struck three drug boats from Venezuela.

Speaker 3 Do you plan to provide proof that these were narcoterists who were on their way to the U.S.?

Speaker 1

Well, we have proof. All you have to do is look at the cargo that was like it spattered all over the ocean.

Big bags of cocaine and fentanyl.

Speaker 5 The war on narco-terrorists continues, and President Trump striking another drug boat, killing three narco-terrorists.

Speaker 1

We're hitting them, as you probably noticed, very hard. And we're blowing the Venezuelan narco-terrorists.

We're blowing them the hell out of the water.

Speaker 4 At time of recording, the Navy has blown up four boats this month, an extreme departure from basic due process and adherence to international humanitarian law.

Speaker 5 In the case of the first strike, the Trump administration says that the crew of the boat were members of Trende Aragua, which is a Venezuelan, formerly prison gang that they've designated as a foreign terrorist organization.

Speaker 4 Joshua Keating is a senior correspondent at Vox. He recently wrote about the dangers of combining the war on drugs with the war on terror.

Speaker 5 They haven't provided any evidence that it was Trende Aragua, and experts I've talked to are pretty skeptical about this story, pointing out Trendo Aragua has no history of transnational drug trafficking.

Speaker 5 It's more known for, you know, extorting people in the areas that it controls, maybe a little local drug dealing, but not this kind of speedboats on the high seas, Pablo Escobar sort of drug trafficking that we're talking about here.

Speaker 4 You quote Anna Kelly, a White House spokesperson, saying that first strike in early September was taken in, quote, defense of vital U.S.

Speaker 4 national interests and in the collective self-defense of other nations.

Speaker 4 What exactly were we defending against?

Speaker 5 Right. So this is basically the White House trying to make the legal case for taking these strikes.

Speaker 5 And the line that's been coming out of the administration is that, you know, drugs are a serious national security threat to the United States and that therefore, you know, anyone bringing drugs into the U.S.

Speaker 5 is a legitimate target. That's just not true.

Speaker 5 There's sort of no precedent for treating narcotics that way. This is a law enforcement matter.

Speaker 5 And the line coming out of Venezuela is that all this is sort of a prelude to a regime change operation, that the real goal of all this is to overthrow the government of Venezuela.

Speaker 5 And it should be pointed out, U.S. officials haven't exactly denied that.

Speaker 4 Yeah, you quoted one U.S. official in your piece saying something like, this was 105% about stopping drug smuggling, but if there were a regime change in the process, no one would complain about that.

Speaker 5 Jr.: Yeah, there was sort of similar rhetoric to this, actually, when Israel was bombing Iran recently, and the U.S. sort of joined in those airstrikes.

Speaker 5

This administration, in particular, has really been at pains to distance itself from George W. Bush-era Republican foreign policy.

Trump constantly attacks neocons and nation builders and globalists.

Speaker 5 So, you know, I think it would be a pretty big shift even for this administration to come out and sort of openly back regime change.

Speaker 4 Aaron Powell, this is something I wanted to ask you about.

Speaker 4 The United States has invaded or backed coups in Nicaragua, Grenada, Puerto Rico, Cuba, Mexico, Honduras, Brazil, the Dominican Republic, Argentina, Haiti, Chile, Costa Rica, El Salvador, Guatemala, Nicaragua, and Peru.

Speaker 4 So clearly there's a sort of history and proclivity to all this. Why do you believe then that the Trump administration is unlikely to, say, invade Venezuela?

Speaker 5 if you look at the Trump administration's foreign policy, they're not actually averse to using military force, as we've seen in Yemen and Iran and several other places.

Speaker 5 But I think there is a resistance to getting bogged down in prolonged ground operations.

Speaker 5 And so if Trump could be convinced that this It's always a risky activity to try to get in his head, but if he were convinced that there are a way to sort of do this with minimal cost, minimal risk of quagmire, maybe that would happen.

Speaker 5 But what we could see are sort of targeted drone strikes or missile strikes against criminal targets on Venezuelan territory, which would be for a variety of reasons pretty destabilizing for the political situation in Venezuela.

Speaker 5 But I think that's sort of different than some of the examples you're talking about.

Speaker 4 Venezuela aside, in February, Trump signed an executive order designating a list of cartels as, quote, foreign terrorist organizations specially designated global terrorists.

Speaker 1 I will direct our government to use the full and immense power of federal and state law enforcement to eliminate the presence of all foreign gangs and criminal networks, bringing devastating crime to U.S.

Speaker 1 soil, including our cities and inner cities.

Speaker 4

These are categories also occupied by ISIS and al-Qaeda. Trenda Aragua was on the list.

What does this designation, this executive order, do exactly, legally or otherwise?

Speaker 5

I think the first thing to point out is what it doesn't do. It's not an authorization for military force.

It doesn't give the U.S.

Speaker 5 military the authority to launch drone strikes or special operations raids or anything else to target these groups.

Speaker 5 The purpose of these listings is to authorize an array of sanctions and to criminalize financial support for these groups.

Speaker 5 So that's legally what it does, but I think it's sort of taken on a different political role.

Speaker 5 The first Trump administration notably listed Iran's Revolutionary Guards as a foreign terrorist organization.

Speaker 5 And that kind of like laid the political path for the drone strike that eventually killed the Iranian general Qasem Soleimani in 2020.

Speaker 5 So as with a bunch of these things, I think we have to distinguish between the actual legal function of this list, which is more limited in scope, and the political function it serves, which is to sort of indicate a level of how seriously we're taking the threat from this group and the severity of the steps we're willing to take to combat it.

Speaker 4 Aaron Powell, Jr.: As many of us learned in civics class in high school or middle school, Congress has the authority to authorize an act of war, which it hasn't in this case.

Speaker 4 Trump, of course, says he doesn't need congressional authorization. Can you give us a bit of that sort of post-9-11 history that helps explain how we got here?

Speaker 5 Congress actually hasn't formally declared war since World War II. What you more often get these days are, you know, what are called authorizations for the use of military force.

Speaker 5 And a notable one was passed immediately after the 9-11 attacks.

Speaker 5 And this is what sort of set the legal basis initially for the war in Afghanistan, but ended up being used for attacks against all sorts of groups, including ISIS, which did not exist at the time of 9-11 and actually was itself at war with remnants of al-Qaeda.

Speaker 5 Now, they're not justifying the strikes on these drug boats in the Caribbean under the 2001 AUMF. They're using the President's Article II powers, basically.

Speaker 5 The president has the legal authority to act without congressional authorization to combat a sort of imminent threat to the national security of the U.S.

Speaker 5 Authorized military force is definitely not designed for something like interducting a boat carrying a bunch of cocaine through the Caribbean.

Speaker 5 But in the years that followed 9-11, the idea of sort of using military force outside of declared war zones against enemies of the United States got sort of normalized to an extent.

Speaker 5 People got used to the idea that the U.S. could launch a drone strike against an armed group in Somalia or Libya that maybe even wasn't actively planning strikes against the United States.

Speaker 5 You know, this is the sort of thing that makes it politically possible, even if there really isn't anything in the law, either criminal law or the laws of war, that authorizes them to do this.

Speaker 4 This week, we saw the Trump administration designate Antifa and the Barrio 18 gang as domestic and foreign terrorist organizations, respectively, even though Barrio 18 was started in the United States and Antifa is not an organization with a central leadership or anything like that.

Speaker 4 What do you make of these announcements?

Speaker 5 I think it's another example of how the kind of politics of the war and terror years live on. As you said, Antifa is not a group.

Speaker 5 Even if it were, the kind of financial tools that were designed to combat al-Qaeda or ISIS or Hezbollah weren't designed for the trend-Araguas and MS-13s of the world, much less Antifa.

Speaker 4 Aaron Powell, but to be clear, the president can't legally designate a domestic group as a terrorist organization. Do I have that right?

Speaker 5

Yes, no, you do have that right. There's no such thing as a domestic terrorist designation.

The FDO is designed for foreign groups.

Speaker 4 If legally naming Antifa as a terrorist organization has no teeth, Why do it at all?

Speaker 5 Aaron Ross Powell: The concern is that it's going to be used to criminalize all sorts of activities, people protesting against ICE raids, in their view, interfering with law enforcement activity.

Speaker 5 All sorts of forms of what they perceive as disorder or illegal activity can be branded as terrorism and therefore

Speaker 5 justify what would normally be considered extra-legal activities.

Speaker 4 Aaron Powell, returning to the drug war side of things, calling people narco-terrorists feels like a way to kind of tap into American fears, rightfully or otherwise, about drugs and terrorism.

Speaker 4 Why do you think that this administration is so keen to ramp up the rhetoric in military operations here?

Speaker 5 Well, it's interesting to me anyway that this comes as they've rebranded the Pentagon from the Department of Defense to the Department of War.

Speaker 5 You know, some people say, oh, this is a more honest depiction of what they are. But, you know, I think at the same time,

Speaker 5 if they're doing that while they're expanding the military's activities into areas that are not traditionally military's area of responsibility, I think it raises questions of what they consider war.

Speaker 5 You know, are we literally at war with narco-terrorists? Are we at war with American cities?

Speaker 5 This administration, it's still evolving, and I think it's too soon maybe to totally define it, but I think they are sort of rethinking the purpose of military power.

Speaker 4

There are so many storylines to keep tabs on right now with this administration. It's frankly head spinning.

Why do you think this drug war in the Caribbean is worth our attention?

Speaker 5 So I've been interested from the beginning in how this administration approaches the Western Hemisphere.

Speaker 5 There was a recently circulated national defense strategy that basically put border security and anti-drug missions above countering adversaries like China and Russia, which had been the sort of primary focus, not just of the last administrations, but the last few.

Speaker 5 In fact, Mike Waltz, the former national security advisor, who's now UN ambassador, sort of described their approach as Monroe 2.0 for referring to the Monroe Doctrine.

Speaker 5 And, you know, I think if you see the sort of threats against the Maduro regime, you know, military operations in the Caribbean, the sort of ongoing threat of the U.S.

Speaker 5 using military force against cartel targets on Mexican soil, the sort of sanctions policy against the Brazilian government to punish them for the treatment of the former President Bolsonaro, Trump's ally, and their sort of close relationship and the sort of discussion of bailing out the government of Malay in Argentina.

Speaker 5 I think we see a remarkably sort of hands-on policy from this administration towards the Western Hemisphere. And it's sort of ironic.

Speaker 5 It's sort of a longtime theme you hear in Washington policy circles that the U.S. has sort of neglected its backyard and that treats Latin America as a backwater.

Speaker 5 For better or worse, it's not a backwater anymore. It seems to be very much front and center of what they're paying attention to.

Speaker 4 Josh, thanks so much.

Speaker 5 Thanks, Micah. Good to be here.

Speaker 4 Josh Keating is a senior correspondent at Vox covering foreign policy and world news. He's the author of the recent piece, What Happens When Trump Combines the War on Drugs with the War on Terror.

Speaker 3 Coming up, the real meaning of Charlie Kirk's murder in the eyes of God, according to men.

Speaker 4 This is on the media.

Speaker 23 This week on the New Yorker Radio Hour, writer and podcaster Ezra Klein, politics is about power.

Speaker 22

And I think people have missed this. Politics is not about self-expression.

Politics is about building coalitions capable of winning power and making the decisions you need to do to do that.

Speaker 23 That's Ezra Klein on the New Yorker Radio Hour from WNYC Studios. Listen wherever you get your podcasts.

Speaker 4 This is on the media. I'm Michael Loewinger.

Speaker 3 And I'm Brooke Gladstone. Last weekend in Glendale, Arizona, tens of thousands of people attended Charlie Kirk's memorial service, including the president.

Speaker 1 Our greatest evangelist for American Liberty became immortal.

Speaker 1 He's a martyr now.

Speaker 3 The vice president.

Speaker 8 He is a hero to the United States of America, and he is a martyr for the Christian faith.

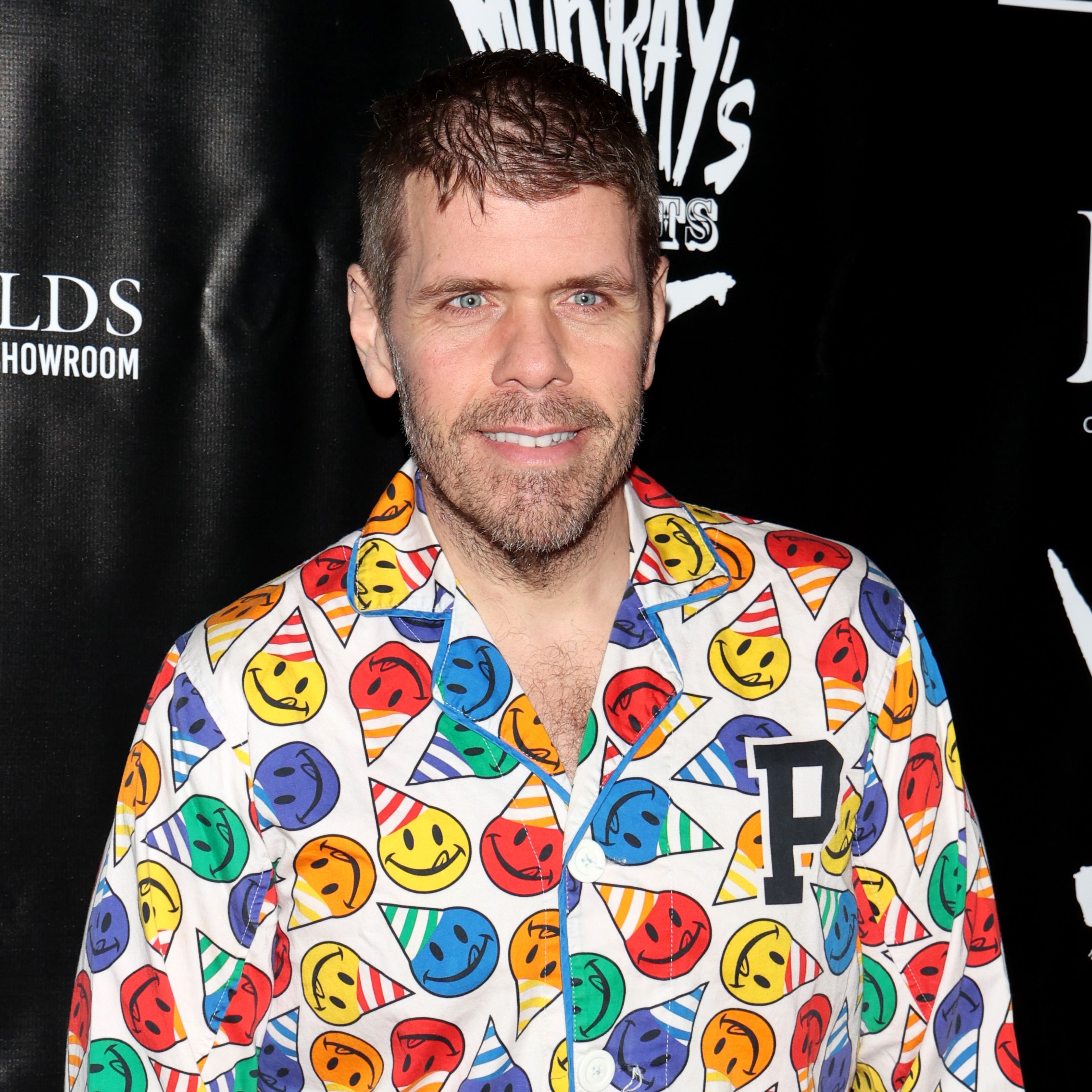

Speaker 3 And Kirk's friend, Pizzagate conspiracy theorist Jack Pasobik.

Speaker 16 On his last day,

Speaker 24

Moses. climbed to the top of the mountain and he saw the promised land.

On his last day, Charlie Kirk was on the top of a mountain and Charlie Kirk led us there.

Speaker 3 Since his murder, Kirk has been likened to countless religious figures, even by prominent Christian leaders.

Speaker 1 I thought, I gotta learn about this guy.

Speaker 3 Cardinal Timothy Dolan, the Archbishop of New York.

Speaker 1

This guy's a modern-day St. Paul.

He was a missionary. He's an evangelist.

He's a hero.

Speaker 3 Conservative outlets reported that Kirk's body was miraculous, repeating the words of a producer for Kirk's mighty youth organization, Turning Point USA, who said he spoke with Kirk's doctor.

Speaker 25 He said, quote, it was an absolute miracle that someone else didn't get killed.

Speaker 25 They did find the bullet just beneath the skin, he says, and even in death, he finishes, that Charlie managed to save the lives of those around him.

Speaker 6 Because there were all of these different forms of Christianity in America that were looking and admiring Charlie Kirk.

Speaker 6 All these different forms of Christianity are now processing his death through their theological matrices. People are trying to figure out which pedestal to put him on.

Speaker 3 Matthew D. Taylor is the senior Christian scholar at the Institute for Islamic, Christian, and Jewish Studies in Baltimore.

Speaker 3 He's been exploring the phenomenon that was and is Charlie Kirk and his movement. He says Christianity wasn't always a central part of Turning Point USA or of Charlie Kirk's public persona.

Speaker 6 If you had asked me circa 2018 what are the most influential religious right or even Christian organizations in the country, Turning Point would not have been anywhere on that list.

Speaker 6 Today, it's probably number one.

Speaker 3 So Christianity was not a prominent feature of Charlie Kirk's conservative advocacy organization, Turning Point USA, but that did change in 2019, right? He met a California pastor named Robert McCoy.

Speaker 6 Yeah, Rob McCoy, who featured fairly prominently in the memorial service, is a pastor with an evangelical denomination called Calvary Chapel.

Speaker 6

And McCoy is a pastor of a church called Godspeak outside of Los Angeles. He has been very involved in local politics.

And he actually was the first church to invite Charlie Kirk to speak there.

Speaker 3 Godspeak exploded in popularity during the pandemic because he flouted the church closure rules.

Speaker 3 He also introduced Kirk to the Seven Mountains Mandate, which we've spoken about before, but give us a refresher.

Speaker 6 So, the Seven Mountain Mandate is a concept that comes out of charismatic evangelical circles. It's sometimes framed as a strategy for cultural conquest.

Speaker 6 It's also a prophecy that people believe was revealed by God to a prophet named Lance Walnell.

Speaker 6 And the idea is that every society can be divided up into seven arenas of cultural influence: education, family, religion, government, arts and entertainment, media, business, and commerce.

Speaker 6 Each of those sectors of society is imagined as a mountain.

Speaker 6 And in this prophecy, the top of those mountains is either controlled by Satan and the demons or by God and the Christians, and there's no in between.

Speaker 6 And so the mandate part is for Christians to take over.

Speaker 6 the seven mountains, to rise to positions of cultural influence, to try to target those specific areas of influence in society, and then to let Christian influence flow down from the tops of the mountain.

Speaker 6 They'll use democracy if it works for them, but the mandate, which they claim is from God, is for Christians to take over society.

Speaker 3 Hence this vision of merging religion and politics that resonated with Kirk. He seems also to have had a personal faith awakening.

Speaker 6 His own descriptions of himself and his life, his family life, shift in that period.

Speaker 3 Was he dating Erica at the time?

Speaker 6

I think they got married in late 2020. And I think that was part of it too.

I mean, Erica Kirk very much comes from the world of evangelicalism.

Speaker 6 She has a JD and a doctorate in Christian leadership from Liberty University. And I think she was a piece of his own, at least personal, movement towards faith.

Speaker 6 I think Charlie Kirk saw in the politics of Rob McCoy in ideas like the Seven Mountain Mandate, a force within American politics that was not being leveraged to its full potential.

Speaker 6 And he really leaned into that and really changed the organization, built out this entire new wing called Turning Point Faith with Rob McCoy, and really has built the thing into a behemoth of the religious right in the United States today.

Speaker 3 You've said that within four years, he became one of the most prominent conservative Christian voices. Charlie Kirk was an abortion absolutist.

Speaker 7 We allow the massacre of a million and a half babies a year under the guise of woman reproductive health.

Speaker 7 It is never right to justify the mass elimination or termination of people under the guise of saying they're unwanted. That's how we get Auschwitz.

Speaker 22 You're comparing abortion to the Holocaust.

Speaker 6 Absolutely I am.

Speaker 7 In fact, it's worse.

Speaker 3 He was also very deep into anti-trans messaging.

Speaker 14 These people are sick and

Speaker 14 I don't say that lightly. I blame the decline of American men.

Speaker 3 The way that McCoy saw it at the memorial, Charlie looked at politics as an on-ramp to Jesus.

Speaker 24 He knew if he could get all of you rowing in the streams of liberty, you'd come to its source, and that's the Lord.

Speaker 6 The politics were really the front door, and it was really the thing that drew Charlie Kirk in the first place. I mean, that was what Turning Point was founded as.

Speaker 6 And the Jesus stuff got added in later.

Speaker 3 During the memorial, conservative podcaster Benny Johnson specifically compared him to the first Christian martyr, Stephen.

Speaker 21 Stephen was killed for speaking the truth about Christ, much like Charlie Kirk.

Speaker 21 The martyr Stephen was the same age as Charlie Kirk when he was martyred.

Speaker 6 At his martyrdom, Stephen gives a very famous speech in the book of Acts, chapter 7.

Speaker 6 So it's one of the first kind of full-fledged presentations of the Christian gospel after the resurrection of Jesus.

Speaker 3 About what year was this, roughly?

Speaker 6 Probably in the late 30s CE, shortly after the death of Jesus, right? The church is just beginning to congeal in Jerusalem.

Speaker 6 And then Stephen's death is at the hands of the Jewish authorities in Jerusalem. But the Apostle Paul is actually a participant in Stephen's execution.

Speaker 6 Then later on, of course, he has his own conversion experience and becomes one of the great missionaries and theologians of the Christian tradition.

Speaker 3 What was the reaction to Stephen's martyrdom?

Speaker 6 The Christian church was obviously devastated by this, but it also Stephen's death is seen as a spur for the growth of the early church.

Speaker 6 And so you can see how for these folks who want to see Charlie Kirk's death as an example of an articulate young Christian cut down in the prime of his life, but who then becomes a spur for revival, the comparison almost makes itself.

Speaker 3 The rhetorical frames around martyrdom, they're not just limited to inspiring a lot of conversions. They can also spur some real violence.

Speaker 6 Yeah, and and this is the dual nature of a martyr narrative, right?

Speaker 6 On the one hand, people like Stephen are seen as models in that they do not provoke, they do not fight back, but instead they accept the persecution, right?

Speaker 6

And Jesus had taught his followers to bless the persecutors, to love their enemies. So that's the one track.

And I think we saw that in Erica Kirk's declaration of forgiveness.

Speaker 3 My husband, Charlie, he wanted to save

Speaker 4 young men,

Speaker 10 just like the one who took his life.

Speaker 6 That man,

Speaker 6 that young man.

Speaker 9 I forgive him.

Speaker 6 I mean, I don't know a Christian who is steeped in the teachings of Jesus who would say that was the wrong choice, right? Jesus taught us to forgive.

Speaker 6 Now, I think Stephen Miller and Donald Trump and the memorial service really embodied the other side of the martyr narrative.

Speaker 1 I hate my opponent,

Speaker 1 and I don't want the best for them. I'm sorry.

Speaker 24 I am sorry, Erica.

Speaker 1 But now Erica can talk to me and the whole group, and maybe they can convince me that that's not right, but I can't stand my opponent.

Speaker 3 The Crusades, that was framed around martyrdom, that godless Muslims or Turks were killing Christians.

Speaker 6 Yeah, when Pope Urban II proclaims the First Crusade in 1095 CE, his rationale for why Christians need to to go and slaughter Muslims and also Jews was that they have devastated the kingdom of God.

Speaker 6 They are killing our brothers and sisters, our fellow Christians in the East, and we need to go and rescue those Christians. But then again, we also need to take back the Holy Land.

Speaker 6 We need to take back Jerusalem because it's a city of Jesus, right?

Speaker 3 And then there's the story of Simon of Trent.

Speaker 6 And yeah, Simon of Trent was a young man who disappeared in the medieval period, and the Christians blamed the Jews.

Speaker 6 And this was part of the blood libel idea of Jewish communities secretively drinking the blood of Christian children as part of their ritual ceremonies.

Speaker 6 And so the disappearance of Simon of Trent leads to pogroms and attacks and becomes part of the conspiracy theory narratives and the vilification of Jews by Christians, right?

Speaker 6 Because a martyr is both a member of the community who is treasured in value, but a martyr is also a symbol that can be wielded for great violence.

Speaker 6 It is one of the most most potent forces in the Christian tradition. This is not merely

Speaker 6 another celebration of life that we witnessed in the memorial or in the collective grieving over Charlie Kirk's death.

Speaker 6 This is a step change in the role of the religious right in American society, and not just in the United States, but around the globe.

Speaker 6 For people who are over the age of 45, I think a lot of them had no idea who he was. And so their impressions of him have been formed entirely in this kind of post-mortem moment.

Speaker 6 But I will say, within right-wing politics, and I realize there will be people who find this comparison deeply offensive.

Speaker 6 I find it a little bit offensive myself, but it is being made widely in right-wing circles.

Speaker 6 They've actually talked about the death of Charlie Kirk as having a similar effect on the global right-wing discourse that the death of George Floyd had on the global left-wing discourse.

Speaker 3 Benny Johnson goes on to say that God establishes the rulers of nations. In the audience right now, there are rulers of our land.

Speaker 21

The State Department, the Department of War, the Department of Justice, the Chief Executive. God has instituted them.

And what

Speaker 4 does the Apostle Paul in Romans say about a godly leadership?

Speaker 16 Rulers

Speaker 21 wield the sword for the protection of good men

Speaker 21 and for the terror of evil men.

Speaker 21 May we pray that our rulers here, rightfully instituted and given power by our God, wield the sword for the terror of evil men in our nation.

Speaker 6 Well, I mean, I don't think anybody summarized the dual martyr narratives better than Benny Johnson in that service, right?

Speaker 6 That on the one hand, Charlie Kirk could be an innocent Steph, but then, right, the turn is now the godly government needs to go after our enemies.

Speaker 3 And this takes me to something that the Christian nationalism scholar Bradley O'Nishi mentioned in his recap of Kirk's memorial. He said that some MAGA factions subscribe to a two-kingdoms theology.

Speaker 2 They believe there's a kingdom of God, and in that kingdom of God, you are going to see God

Speaker 2 who operates according to peace and justice and love.

Speaker 2

But there's also the civil kingdom. When it comes to the political realm, the civic realm, it's really about a friend-enemy distinction.

It's either you or them. It's either dominate or be dominated.

Speaker 2 And when it comes to the two kingdoms theology, we want a woman who forgives the man that murdered her husband. And we want a president who's going to hate him enough to execute him.

Speaker 2 They say openly that hate is a way to love God.

Speaker 6 When we see a political coalition built around antipathy, aggressive politics, castigating people who disagree with them, fighting with their enemies, when that names itself as Christian and also embraces some of the rhetorical styles and vocabulary of Christianity, it becomes very hard to disentangle those things.

Speaker 6 And I think Trump has played this dual role for American Christians over the last 10 years.

Speaker 3 Dual? Isn't he just playing on the second string?

Speaker 6 No, Donald Trump will sometimes mouth the pieties, especially since the assassination attempt in Butler, Pennsylvania. God saved me so that I could save America.

Speaker 5 Right?

Speaker 6 That's a message that a lot of American Christians want to hear, but that's also not about Jesus, right?

Speaker 6 And so Trump can present himself as a Christian, but he does not always conform to Christian morality.

Speaker 6 And the Christians give him a pass because they want to say, well, he's the one God has put in office. He is there to punish our enemies.

Speaker 6 So we can say that we love our enemies and celebrate their demise at Donald Trump's hands.

Speaker 6 It's very difficult in a democracy when

Speaker 6 narratives that are not shared by everyone are declared sacred, untouchable, and holy.

Speaker 6 A democracy assumes that there's plurality of views and democratic systems are there to kind of manage those disagreements and channel them into useful and productive conversations and elections and debates.

Speaker 6 And I worry that Charlie Kirk's death, the way that has been turned into this attack on free speech, contributes to the polarization of our politics.

Speaker 6 And I really do worry that it is driving a mass radicalization of Christians around these narratives of persecution. The left is against us, this kind of nefarious and ambivalent signifier of they.

Speaker 3 It's the dehumanization that concerns me.

Speaker 6 It is the dehumanization that concerns me as well. It's a cancer that will kill a democracy in the long term.

Speaker 3 Thank you so much.

Speaker 6 Thank you, Brooke.

Speaker 3 Matthew D.

Speaker 3 Taylor is the senior Christian scholar at the Institute for Islamic, Christian, and Jewish Studies in Baltimore, and he's the author of The Violent Take It by Force, the Christian Movement that is threatening our democracy.

Speaker 4 That's it for this week's show. On the Media is produced by Molly Rosen, Rebecca Clark Callender, and Candice Wong.

Speaker 3

Our technical director is Jennifer Munson with engineering from Jared Paul. Eloise Blondio is our senior producer, and our executive producer is Katya Rogers.

On the Media is produced by WNYC.

Speaker 3 I'm Brooke Gladstone, and I'm Michael Lewinger.