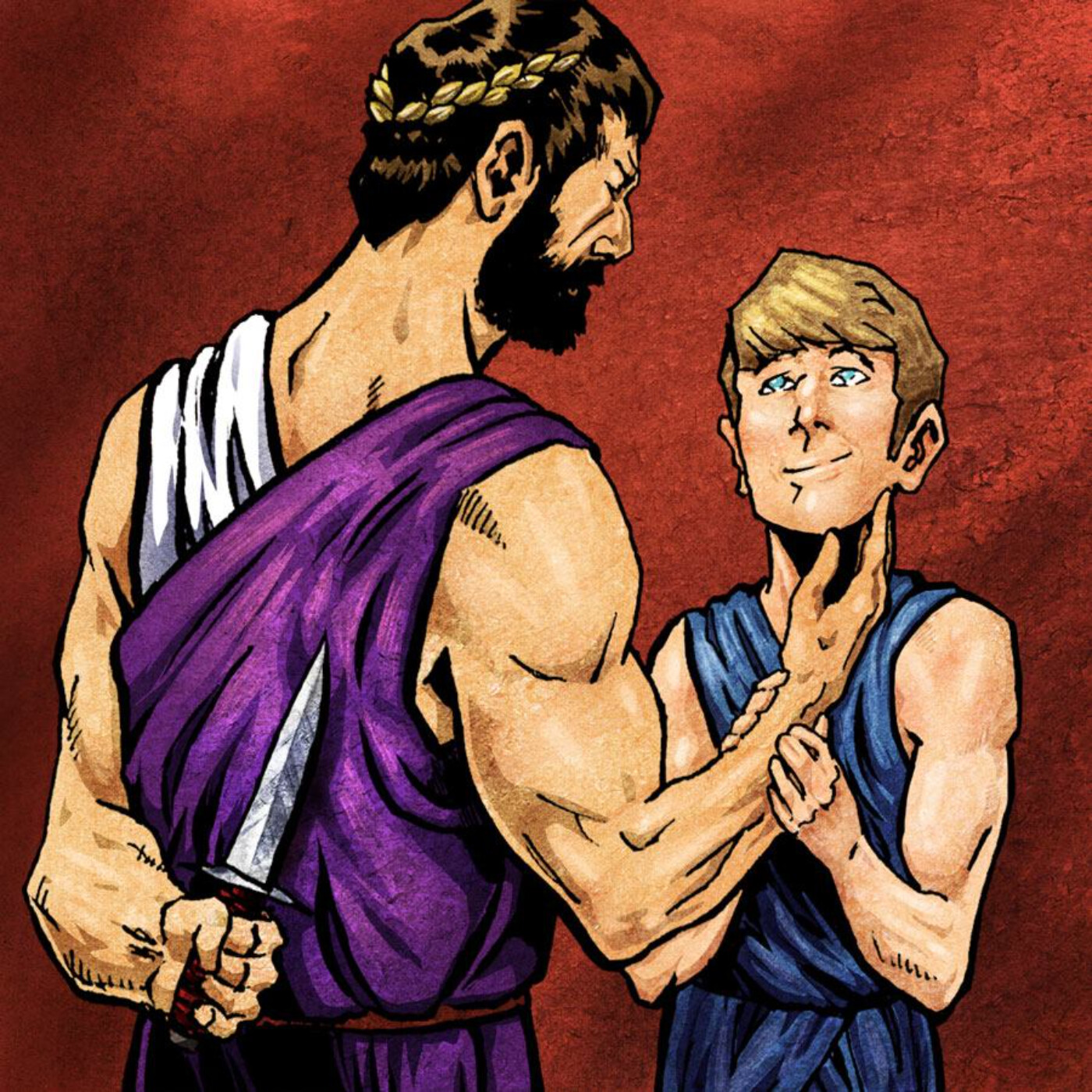

OFH Throwback- Episode #72 - Did Emperor Hadrian Murder His Teenage Lover?

In this throwback episode Sebastian takes you back to the start of Season 4 to explore the historical reputation of the Roman Emperor Hadrian. Hadrian has been celebrated as one of Rome’s “five good emperors”, but is that reputation actually deserved? Hadrian’s reputation is complicated by the mysterious death of his teenage lover, Antinous. What should we believe about this strange chapter in the life of one of Rome’s most celebrated emperors? Tune-in and find out how radical beards, fantastical walls, and ancient man-love all play a role in the story.

See Privacy Policy at https://art19.com/privacy and California Privacy Notice at https://art19.com/privacy#do-not-sell-my-info.

Press play and read along

Transcript

Speaker 1 This message comes from Capital One. The Capital One Venture X Business Card has no preset spending limit, so the card's purchasing power can adapt to meet business needs.

Speaker 1 Plus, the card earns unlimited double miles on every purchase, so the more a business spends, the more miles earned.

Speaker 1 And when traveling, the Venture X Business Card grants access to over a thousand airport lounges. The Venture X Business Card: What's in your wallet? Terms and conditions apply.

Speaker 1 Find out more at capital1.com/slash venturex business.

Speaker 2 We're spending more than ever. I hate my job.

Speaker 1 The price of everything has gone.

Speaker 2 AI is threatening my job.

Speaker 3 It's crisis after crisis.

Speaker 2 Nothing is working out.

Speaker 3 I can't find a new one disaster.

Speaker 2 Take control of change.

Speaker 2 I need a change.

Speaker 2 Disruption is the force of change.

Speaker 2

Stop the chaos. Stop the madness.

Take control. Read James Patterson's Disrupt Everything and win.

Speaker 2 Hello and welcome to this very special throwback episode of Our Fake History.

Speaker 2 Today I am throwing you back to the very first episode of season four.

Speaker 2 That was episode number 72 titled, Did Emperor Hadrian Murder His Teenage Lover?

Speaker 2 Now, the story of how this particular episode came to be is a little different than most our fake history episodes.

Speaker 2 This is one of the few times I've let myself be influenced by outside forces about what topic I should pick for the show. Let me tell you the tale.

Speaker 2 A friend of mine was working at the Canadian Opera Company, and they had this new opera coming up that was going to be about the life of Hadrian and his lover lover Antinous that had been written by the great Canadian songwriter Rufus Wainwright.

Speaker 2 Yes, Rufus Wainwright also writes operas.

Speaker 2

So he calls me up and says, Sebastian, we're doing this really cool opera. It's based on Roman history.

It might make for an amazing story on our fake history.

Speaker 2 And I'm like, oh, you want to do like a cross-promotion? And he's like, well, the Canadian opera company doesn't really have a lot of money for this sort of thing. Just look into the story.

Speaker 2 If you like it, then maybe I can hook you up with some opera tickets if you end up doing an episode on this topic.

Speaker 2 So, yeah, not really like a brand integration thing, more like, hey, wouldn't it be cool if there was a little bit of synergy here?

Speaker 2 And so I was like, okay, I'll check out this story. And you know what? The story was so interesting, I had to do it.

Speaker 2 So you will hear me say in this episode that there's this opera going on at the Canadian Opera Company about the life of Hadrian and Antinous.

Speaker 2 And full disclosure, what did I get for doing this? Two free tickets to the opera.

Speaker 2 Now, there is kind of a cool bookend to this story because when my wife and I eventually went and saw the performance of Hadrian and Antinous at the Canadian Opera Company, my wife was very pregnant with our first child.

Speaker 2 One of the very first times that I felt my first child kick from inside the womb was at this opera.

Speaker 2 There was something about the vibrations of the music that, you know, got him going, and he was kicking throughout that entire performance.

Speaker 2 Now, this was kind of intense and poetic for me because it mirrors one one of our family stories about my middle name.

Speaker 2 For those of you that don't know, my middle name is Amadeus, and it's because when I was in the womb, my parents went and saw that movie in the theaters, and apparently I started kicking like crazy.

Speaker 2 So my parents joked that my middle name would be Amadeus.

Speaker 2 And when it came time to fill out the paperwork, it wasn't so much a joke anymore and just became my real middle name.

Speaker 2 So when my own son started kicking like crazy during that opera, my wife and I started to joke that maybe his middle name should be Hadrian.

Speaker 2 But unlike my parents, who are courageous and awesome, we were cowards and couldn't go through with it. So his middle name is not Hadrian today.

Speaker 2 But I will never forget that opera because it was such an amazing moment for my wife and I and our new family.

Speaker 2

And I will say, the opera was really cool, edgy, intense. The music was incredible.

I truly loved it. I'd never seen any opera before, and it got me interested in opera generally.

Speaker 2

So, honestly, go to the opera. Even if you think you're not going to like it, the opera is way cooler than you might imagine.

So, check it out.

Speaker 2 This throwback episode also tees us up for our next series.

Speaker 2 The Emperor Hadrian was a known Grecophile, meaning he loved the Greeks.

Speaker 2 Well, we love the Greeks as well here on Our Fake History, and our next series will be dealing with some of the most mythological elements of Greek history, specifically something called the Spartan Mirage.

Speaker 2 In the meantime, enjoy this throwback to episode number 72. Did Emperor Hadrian Murder His Teenage Lover?

Speaker 2 In the year 130 AD, the Roman Empire was approaching the peak of its power and influence.

Speaker 2 The Mediterranean Sea was little more than a Roman lake, and even Rome's most fierce civilizational rivals had been humbled before the power of the legions.

Speaker 2 Sometime in the fall of that year, a body washed up on the shores of the river Nile.

Speaker 2 This was a particularly beautiful body. It was the body of a young man who would soon be worshipped as a god.

Speaker 2 This was the fresh corpse of a young man named Antinous.

Speaker 2

Antinous was not just any beautiful youth. He was the lover and favorite of the Roman Emperor Hadrian.

His mysterious death was about to raise a number of uncomfortable questions about the emperor.

Speaker 2 How had this young man just entering the prime of his life come to die? Had it been a tragic accident or was foul play involved? Had the emperor himself been involved in a murder?

Speaker 2 Antinous's life and tragic death pose a number of questions about the historical reputation of the emperor Hadrian.

Speaker 2 For the most part, Hadrian has been celebrated as one of Rome's best and most enlightened rulers. But we need to ask if that reputation is actually justified.

Speaker 2 Should Hadrian's standing as one of Rome's so-called five good emperors be questioned?

Speaker 2 Was he simply a gifted administrator who helped solidify Rome's position as a global superpower? Or was he a lecherous and murderous old man who indulged his every whim, no matter how sadistic?

Speaker 2 Should we rank Hadrian with Augustus and Trajan as one of the best Roman emperors? Or should he instead be lumped in with Caligula and Nero as one of the most debased?

Speaker 2 Hadrian's complex and often mysterious relationship with the teenager named Antinous is at the heart of this historical debate. Should we give Hadrian the benefit of the doubt?

Speaker 2 Or is it time that he gets taken down a few pegs when we start ranking our Romans?

Speaker 2 Let's find out today on the first episode of season four of our fake history.

Speaker 2 One, two, three, five

Speaker 2 Episode number seventy-two:

Speaker 2 Did Emperor Hadrian murder his teenage lover?

Speaker 2 Hello, and welcome to Our Fake History.

Speaker 2 My name is Sebastian Major, and this is the podcast that explores historical myths and tries to determine what's fact, what's fiction, and what is such a good story that it simply must be told.

Speaker 2 Welcome back, everyone. It is the beginning of season four, and I am so excited to to be back in front of the mic and talking to all of you.

Speaker 2 To inaugurate our fourth season, we are heading back to ancient Rome to explore some particularly contentious moments in the life of one of Rome's most storied emperors.

Speaker 2 This was Publius Aelius Hadrianus, or as he is more commonly known in English, the Emperor Hadrian.

Speaker 2 Hadrian is one of those Roman emperors that has better name recognition than most.

Speaker 2 Many of his ambitious building projects, including a massive series of defensive walls and military forts, are still standing today.

Speaker 2 If you've never heard of the Emperor Hadrian himself, then there's a good chance that you may have heard of Hadrian's Wall.

Speaker 2 The remains of that massive defensive structure are still visible today in northern England and continue to be a notable tourist attraction.

Speaker 2 That site has gotten even more attention lately since word got out that Hadrian's Wall was the historical inspiration for the fantastical wall in Game of Thrones.

Speaker 2 That's the one that guards Westeros from the demonic white walkers.

Speaker 2

But for those of you who aren't Roman history buffs, your knowledge of the Emperor probably ends there. Hadrian, he's the guy with the wall.

Got it.

Speaker 2 But as you might imagine, there is considerably more to the emperor Hadrian than his famous walls.

Speaker 2 Hadrian has an incredibly complex historical reputation that is fraught with myth-making, propaganda, and some attempts at character assassination.

Speaker 2 Now,

Speaker 2 At first, this came as a bit of a surprise to me. I had always known Hadrian as one of the so-called five good emperors of Rome's golden age.

Speaker 2 The genesis of the term the five good emperors is usually attributed to the famous Renaissance humanist Niccolo Machiavelli.

Speaker 2 That's the same Machiavelli who would eventually write the notorious handbook for the powerful known as the Prince. When he wasn't writing political theory, Machiavelli also dabbled as a historian.

Speaker 2 In his opinion, the emperors who reigned from 96 to 180 AD had been exceptionally capable. In his estimation, the five good emperors were Nerva, Trajan, Hadrian, Antonius Pius, and Marcus Aurelius.

Speaker 2 Now, this particular interpretation was reinforced by Edward Gibbon in his incredibly influential history, The Decline and Fall of the Roman Emperor. He famously declared, quote,

Speaker 2 if a man were called upon to fix that period in the history of the world during which the condition of the human race was most happy and prosperous, he would, without hesitation, name that which elapsed from the deaths of Domitian to the accession of Commodus.

Speaker 2 End quote.

Speaker 2 Domitian and Commodus were the notably bad emperors who bookended this particularly prosperous age.

Speaker 2 According to these two eminent sources, Hadrian fell right smack in the middle of what they determined to be the Roman Empire's golden age.

Speaker 2 If you stopped your examination there, you might happily conclude that Hadrian must therefore be the golden est of the golden age emperors.

Speaker 2 But a closer examination of Hadrian's life and reign shows us that he was a considerably more divisive figure in his own time.

Speaker 2 Many of his contemporaries, especially those who held the rank of senator in the Roman government, did not see Hadrian as a particularly great leader.

Speaker 2 In fact, some believed that his policies were actively leading the empire backwards and inevitably into ruin. His enemies saw him as vain, arrogant, and decidedly un-Roman.

Speaker 2 They even believed that the emperor was willing to murder in order to protect his fragile ego.

Speaker 2 To historians like Machiavelli and Gibbon, Hadrian ranked alongside Augustus as one of the empire's greatest leaders.

Speaker 2 But to many of his contemporaries, Hadrian was less of an Augustus and more of a Nero. delighting as Rome burned.

Speaker 2 Now, the reason I've been thinking about Hadrian so much lately is because the Canadian opera company is mounting a brand new opera about the Roman Emperor.

Speaker 2 The music was all written by the great Canadian singer and songwriter Rufus Wainwright, and the libretto comes from the great Canadian playwright Daniel MacIver.

Speaker 2

So, this is going to be pretty cool. I'm actually fascinated to see how this opera takes on the life of Hadrian.

After all the research I've done, I'm still not sure what to make of the guy.

Speaker 2 If you're going to be in Toronto in the next few months, that's October, November of 2018, and you're curious about this opera, then listen to the end of the show and I'll tell you more about it.

Speaker 2 I think it sounds pretty cool. Anyway, what should we believe about this particular Roman emperor? Does Hadrian deserve his reputation as one of the five good emperors?

Speaker 2 Or should his status be downgraded? Well, there are many ways we could go about answering that question.

Speaker 2 Hadrian had a long and storied reign that could easily make for a huge series of podcasts. But for this one, I'm going to be a little less exhaustive than I have been in the past.

Speaker 2 Instead, I want to focus on a few particularly contentious moments in Hadrian's life. Specifically, those moments that are fraught with speculation and fake history.

Speaker 2 In particular, I want to examine the Emperor's relationship with the young Antinous and see what we can conclude about the youth's mysterious death.

Speaker 2 To do this right, we need to discuss Hadrian's sexuality. So, a small warning for what's coming up ahead: there will be a very frank discussion of Hadrian's sex life.

Speaker 2 So, if you're listening with a younger person who may not be ready for a very,

Speaker 2 let's call it real take on ancient sexuality, then

Speaker 2

perhaps they should not listen to this one. Sorry, the first one back's got to come with a caveat, but that's how it goes.

So, listener discretion is advised. All right, so

Speaker 2 was this quote-unquote good emperor actually capable of cold-blooded murder? Before we can answer that question, let's first get some background on Hadrian and understand who he was and how he ruled.

Speaker 3

Suffs, the new musical has made Tony award-winning history on Broadway. We the man to be winner best score.

We the man to be seen. Winner, best book.

We the man to be quality.

Speaker 3 It's a theatrical masterpiece that's thrilling, inspiring, dazzlingly entertaining, and unquestionably the most emotionally stirring musical this season.

Speaker 3 Suffs, playing the Orpheum Theater, October 22nd through November 9th. Tickets at BroadwaySF.com.

Speaker 2

Hey, Zach, are you smiling at my gorgeous canyon view? No, Donald. I'm smiling because I've got something I want to tell the whole world.

Well, do it. Shout it out.

T-Mobile's Got Home Internet.

Speaker 2

Minute Ed. Minute Ed.

Whoa, I love that echo. T-Mobile's Got Home Internet.

Internet. How much Jesus?

Speaker 2 Look at at that zach we got the neighbors attention just 35 bucks a month and you love a great deal denise plus they've got a five-year price guarantee that's five whole trips around the sun i'm switching

Speaker 2 yes t-mobile home internet for the neighborhood

Speaker 2 you still haven't returned my weed whacker Carl, don't you embarrass me like this, please? What's everyone yelling about? T-Mobile's got home internet. Then Donald's got my weed whacker.

Speaker 2

Yes, T-Mobile's got home internet. Just 35 a month with autopay and any voice line.

And it's guaranteed for five years.

Speaker 2

Beautiful yodeling, Carl. Taxes of these apply.

Ctmobile.com slash ISP for details and exclusions.

Speaker 2 Before we jump into Hadrian's career as a Roman emperor, I think we need to orient ourselves within the wider scope of Roman history. Hadrian became emperor in the year 117 AD.

Speaker 2 But where exactly was the Roman Empire at that point in history?

Speaker 2 Well, in 117, Rome was deep in the imperial phase of its existence.

Speaker 2 The Roman Republic had more or less been destroyed nearly 150 years earlier when Augustus Caesar emerged victorious from the civil wars and established the position of emperor.

Speaker 2 At the time, he was clever enough to do this in a way that still retained the trappings of Republican government.

Speaker 2 He kept the Senate as an institution and named himself merely Princeps, which roughly translated to first citizen.

Speaker 2 However, the Senate was stripped of any real authority, and from then on in Rome was essentially controlled by one person at the top of the chain.

Speaker 2 By the time we get to Hadrian's age, the Romans had been living in this system for well over a century, and few questioned it.

Speaker 2 There had been good emperors and there had been absolutely disastrous emperors, but the idea that Rome should be controlled by one strong executive was firmly established.

Speaker 2 The Senate still existed, but it was less of a political force and more of an elite social club for influential aristocrats.

Speaker 2 The Senate still needed to be considered, but only so much as any king needs to consider the moods of his wealthy and influential courtiers.

Speaker 2 In 117 AD, Rome was also nearing the peak of its military and cultural dominance. The Mediterranean Sea had been completely encircled by the Roman Empire for generations,

Speaker 2 and the Empire had not faced a meaningful military defeat in recent memory.

Speaker 2 The emperor who directly preceded Hadrian was Trajan. Now, if you're going to make a list of all-time greatest Roman emperors, Trajan would probably make the top three.

Speaker 2 Trajan was the kind of emperor that the militaristic Romans loved,

Speaker 2 because above all else, he was a brilliant and successful general. Under Trajan, the Roman Empire reached its largest territorial extent.

Speaker 2 Trajan commanded the legions in a stunning series of campaigns that resulted in the creation of a number of new Roman provinces, which hugely enriched the empire.

Speaker 2 Perhaps most significantly, Trajan waged a successful successful war against Rome's chief civilizational rival, the Parthians.

Speaker 2 By the time he was done, Trajan had sacked the Parthian capital, dethroned the king, and had annexed both Mesopotamia and Armenia.

Speaker 2 Up until that point, the Romans had a pretty sketchy record when trying to invade Parthian territory. But Trajan had done it.

Speaker 2 On top of that, he instigated a number of impressive building projects and instituted new forms of social welfare that made him incredibly popular with the people.

Speaker 2 Usually, the greatness of a ruler is something that is judged after the fact with the benefit of hindsight. But in Trajan's case, even his contemporaries knew that the guy was the best.

Speaker 2 The Senate even invented a new honorific title for him, Princeps Optimus. That basically translates to the best ruler.

Speaker 2 After Trajan's awe-inspiring turn as emperor, all future emperors would be sworn in with a blessing that translated to,

Speaker 2 may you be luckier than Augustus and better than Trajan, end quote.

Speaker 2 All of this is to say that our boy, Hadrian, had a pretty tough act to follow. In the eyes of his contemporaries, he would never quite live up to Trajan.

Speaker 2 But to be fair, it's hard to be better than the best.

Speaker 2 Hadrian's glowing historical reputation is something that was established much later by historians.

Speaker 2 During his lifetime, there were many that saw his reign as a massive step backwards after Trajan's thoroughly impressive 20-year run.

Speaker 2 Hadrian was related to Trajan only distantly. Trajan was technically Hadrian's father's first cousin, but both men had been born and raised in the city of Italica in Roman-ruled Spain.

Speaker 2 This was notable because it meant that both Trajan and Hadrian were seen as rough provincials by the snobby Roman elite.

Speaker 2 One of Hadrian's later biographers would try and claim that Hadrian was born in Rome while his parents were visiting on vacation, but most historians now see that as a bit of revisionism in order to make Hadrian sound like he had better pedigree.

Speaker 2 Apparently, the Romans used to make fun of Hadrian's accent when he first entered public life. That's tough.

Speaker 2 As Trajan's star rose both as a military man and as a Roman politician, he saw to it that his younger male relative was properly educated and groomed for a life among Rome's ruling class.

Speaker 2 However, many historians have pointed out that Trajan always kept Hadrian at arm's length and never once made it clear that he was considering the young man to be his heir.

Speaker 2 Hadrian was never given the kind of attention or impressive postings that one might expect from an heir apparent.

Speaker 2 Hadrian steadily advanced up the rungs of the Roman political ladder, but he never once seemed to be singled out as the future ruler of the empire.

Speaker 2

Now, this was not for lack of ability. From a young age, Hadrian distinguished himself as a keen and inquisitive student.

He very quickly developed a love for all things Greek.

Speaker 2 He couldn't get enough of Greek theater, Greek architecture, Greek sculpture, and especially Greek philosophy.

Speaker 2 All aristocratic Romans in this era were educated in Greek classics, usually by Greek slaves, but it was considered somewhat inappropriate to become too enthusiastic about Greek culture.

Speaker 2 The Romans, who even in their most decadent days still perceived themselves as tough yeoman farmers, thought that too much Greek influence could make someone corrupt and weak.

Speaker 2 Well, Hadrian clearly was not phased by this prejudice and wore his love of things Greek on his sleeve. He even earned the nickname Grecolus, which roughly translates to the Greekling.

Speaker 2 I bring this up because it can help us understand why many of Hadrian's contemporaries viewed him with such suspicion. He was a Spanish provincial who was obsessed with the Greeks.

Speaker 2 To some, some, this made him positively un-Roman.

Speaker 2 Hadrian's somewhat surprising ascension to the office of emperor was also viewed with some serious suspicion, and sometimes even contempt by his contemporaries.

Speaker 2 In this era, it became common for emperors to not simply pass on the title to their oldest son, but instead to choose a capable man from among the ranks of the aristocracy and formally adopt that person as their son and heir.

Speaker 2 This custom of adopting a capable person and making them the emperor is what many historians think made this period so prosperous.

Speaker 2 The emperor's kids weren't just getting the job by virtue of being related to the top guy. Some capable person would be singled out and then a formal adoption would take place.

Speaker 2 Trajan had become emperor after he had been adopted by Nerva.

Speaker 2 But Trajan, on the other hand, had been much more cagey about who would succeed him. If you adopted someone too soon in your reign, it could look like you were abdicating early.

Speaker 2 However, if you waited too long to make your successor known, then you could potentially plunge the empire into civil war as powerful aristocrats and military commanders fought for their right to wear the purple.

Speaker 2 What's interesting is that it was not ever clear that Trajan wanted Hadrian to be his successor. But it does seem very clear that Trajan's wife Platina very much favored Hadrian.

Speaker 2 There's some debate on this, but many historians have argued that Platina was hugely instrumental in Hadrian's rise to power.

Speaker 2 She may have even been behind his political marriage to Trajan's grandniece named Vibia Sabina. This marriage was famously unhappy for reasons we will be getting into in a few moments.

Speaker 2 Plotina seems to have orchestrated it in order to make Hadrian a better candidate to be Trajan's successor.

Speaker 2 If Hadrian was married to a member of Trajan's family, then their familiar ties were even closer, and he looked like a more likely heir.

Speaker 2 Now, it's unclear exactly why Plotina took a shine to young Hadrian, but historians have speculated that she shared his cosmopolitan view of the Roman Empire.

Speaker 2 This was a belief that the status quo shouldn't just be Romans from Rome lording it over the provincials.

Speaker 2 The Roman identity instead should be shared by the the whole empire so long as it was underpinned by a classical Greco-Roman religion and culture.

Speaker 2 But aside from these more high-minded reasons, Plotina may have just been thinking about self-preservation.

Speaker 2 If Hadrian was emperor, then her family and other Spanish Roman elites would remain at the top of the heap.

Speaker 2 When it comes to Trajan's death and Hadrian's succession, our sources tell two very different stories.

Speaker 2 According to the Historia Augusta, the official history approved by the emperors, Trajan had picked Hadrian as his successor years before his death and had even sealed the promise by giving Hadrian a ring that had once been given to him by the emperor Nerva.

Speaker 2 However, the Historia Augusta always needs to be taken with a grain of salt, as it's essentially a form of state propaganda meant to legitimize the office of emperor.

Speaker 2 That doesn't mean it's always lying, just that it comes with a huge bias.

Speaker 2 Our other main source, the ancient historian Cassius Dio, tells a very different story about Hadrian's succession. According to Dio, Trajan never officially adopted Hadrian, not even on his deathbed.

Speaker 2 Dio tells us that the entire adoption was orchestrated by Plotina. According to Dio, Plotina kept Trajan's death secret for a number of days after he died.

Speaker 2 She even went so far as to hire an actor to portray him while she hatched her plot. After Hadrian was dead, she drew up the official adoption papers and then signed them herself.

Speaker 2 So if we accept this account, then that means that Trajan maybe never wanted Hadrian to be the emperor, and Hadrian's succession was basically a usurpation.

Speaker 2 Dio goes on to tell us that the linchpin of Plotinus' whole plan was to make sure that Hadrian got the news of Trajan's death before anyone else.

Speaker 2 Now at the time, Hadrian was acting as the governor of Syria and was commanding the legions of the Eastern Empire. So when Hadrian got the news, he broke it to his legions.

Speaker 2 They were hearing this way before the Senate in Rome or anyone else for that matter. Once they heard that Trajan had died, the legions then spontaneously hailed Hadrian as the new emperor.

Speaker 2 Now, the word spontaneously really needs to be in some serious air quotes. These quote-unquote spontaneous moments were usually highly staged-managed affairs.

Speaker 2 The soldiers were told well in advance by their superiors exactly what they were supposed to say and when they were supposed to say it.

Speaker 2 By the time the Senate in Rome got news of Trajan's death, Hadrian's succession was a fait accompli.

Speaker 2 The adoption papers were complete, and the Eastern Legions, the most numerous and powerful military force in the Empire, had already named him Emperor.

Speaker 2 Hadrian could now play the good guy, writing the Senate that he was so sorry that his legions had gone ahead and done this. Oh my god, this is so embarrassing.

Speaker 2 They were just merely overly enthusiastic. Of course, he would only take up the mantle of princeps if the honorable fathers of the Senate would have it so.

Speaker 2 With little other choice, the Senate begrudgingly went along, and Hadrian was given all the titles and honors due to a new emperor.

Speaker 2 But there were many powerful Romans who always perceived Hadrian's rise as a little too sneaky.

Speaker 2 The always misogynistic Romans didn't care for the idea that the backroom dealings of a woman may have been behind the ascension of their new emperor.

Speaker 2 It all fit with a growing negative perception of Hadrian, that he was a sneaky, effeminate, Greek-loving bookworm.

Speaker 2 But despite the trepidation of some of Rome's aristocratic class, Hadrian's ascension was completely secured. He faced no meaningful resistance from the Senate or any other powerful leaders in Rome.

Speaker 2 But that didn't mean that they liked him.

Speaker 2 As emperor, everything from Hadrian's policy decisions, military strategies, and personal style would rankle Roman conservatives.

Speaker 2 Even the emperor's sexuality was seen as an affront to proper Roman virtues.

Speaker 2 So let's take a closer look at Hadrian's time as emperor and specifically his relationship with one teenage boy and see if we can understand why our so-called good emperor was so distrusted in his own time.

Speaker 4 You want your master's degree.

Speaker 2 You know you can earn it, but life gets busy.

Speaker 4 The packed schedule, the late nights, and then there's the unexpected. American Public University was built for all of it.

Speaker 4

With monthly starts and no set login times, APU's 40-plus flexible online master's programs are designed to move at the speed of life. Start your master's journey today at apu.apus.edu.

You want it?

Speaker 4 Come get it at APU.

Speaker 2 As the emperor of Rome, Hadrian was a bit of a maverick. His reign was characterized by nearly constant travel.

Speaker 2 He spent less time in the actual city of Rome than any other emperor that had preceded him.

Speaker 2 He spent most of his time touring Rome's many provinces and generally micromanaging the development of many of the empire's far-flung holdings.

Speaker 2 To modern observers, Hadrian's travels are often perceived as a good thing.

Speaker 2 Hadrian was promoting cohesion amongst a massive empire and was actively encouraging a pan-Hellenic or Greek-inspired culture everywhere he went.

Speaker 2 To historians, this can can look like sound leadership. To many of his contemporaries, this looked like someone who had turned his back on the city of Rome itself.

Speaker 2 At this point in Roman history, there was still an idea of Italian exceptionalism.

Speaker 2 That is, that people from the boot-shaped peninsula were the true Romans and therefore deserved more of the spoils of empire.

Speaker 2 Hadrian was starting what would be a long process of Italy becoming just another Roman province. But as you can imagine, this was hardly popular among the more traditionally minded Romans.

Speaker 2 Then, of course, there was Hadrian's military policy. Hadrian believed that Trajan's aggressive expansion of Rome's borders had stretched the empire too thin.

Speaker 2 So he did the enormously unpopular thing and ordered Rome's legions to pull back to more easily defensible positions.

Speaker 2 This meant abandoning many of the gains made against the Parthians in Mesopotamia, gains that were a particular source of pride for the Romans.

Speaker 2 This was part of an empire-wide policy of what some have called an aggressive defense.

Speaker 2 Anywhere it seemed like the legions had been pushed too far, Hadrian had them pull back and start building new fortifications.

Speaker 2 At his direction, a massive series of walls and forts were built across the empire. These were intended to properly demarcate Rome's borders and make the empire that much easier to defend.

Speaker 2 Hadrian's Wall in northern Britain is just one example of a myriad of similar defensive structures that popped up around the Empire during Hadrian's reign.

Speaker 2 So, as much as those northern Celtic tribes were fierce,

Speaker 2 the wall was not just for them.

Speaker 2 This military policy, which historians often look at as sensible and potentially empire-saving, was viewed as cowardly and positively un-Roman by many of Hadrian's contemporaries.

Speaker 2 Rome was supposed to be constantly expanding. Romans didn't pull back.

Speaker 2 One of the most interesting explanations for why the Romans hated this policy that I've ever heard comes from Mike Duncan's History of Rome podcast.

Speaker 2 If you haven't checked that out, I mean, it's an absolute classic of history podcasting.

Speaker 2 Mike Duncan pointed out that the Romans worshipped an obscure god named Terminus, who was basically a god of boundaries.

Speaker 2 In Roman mythology, when Terminus set a new boundary, not even Jupiter himself could move it.

Speaker 2 When Rome set a new border, that boundary was thought to be set by Terminus and could not be moved. But here comes Hadrian, a mere mortal, picking up Terminus's boundary and moving it back.

Speaker 2 So this may have been seen not only as cowardly, but also as deeply unpious.

Speaker 2

This was an affront to the gods. Thanks, Mike Duncan.

I like that take.

Speaker 2 Now, even Hadrian's personal fashion sense seemed to be a challenge to traditional Roman sensibilities. Hadrian was the first Roman emperor to grow a beard.

Speaker 2 Now, this probably doesn't sound like a big deal, but you have to remember that Roman aristocrats had sported a distinctive clean-shaven look for centuries. Caesar did not have a beard.

Speaker 2 Hadrian's choice to grow a beard could have been perceived as yet another jab at conservative Romans. But most historians don't necessarily see it that way.

Speaker 2 Some believe that Hadrian grew the beard in emulation of his Greek philosopher heroes, or perhaps as a way to connect with rank and file soldiers who often wore beards.

Speaker 2 Or perhaps it was simply to hide a pockmarked face. Most historians don't believe that he was doing this just to annoy conservative Roman senators.

Speaker 2 Nevertheless, a bearded face represented a break with tradition, and breaking with tradition was becoming a hallmark of Hadrian's reign.

Speaker 2 But perhaps just as scandalous as Hadrian's bearded face was his sexuality.

Speaker 2 Hadrian was homosexual and seemed to have a particular attraction to teenage boys. Now, before we dive into this, I think we need to get some context on sexuality in the ancient world.

Speaker 2 As we've explored in past episodes, homosexuality in the ancient and medieval worlds was not associated with a psychological or social identity the way it has been in modern times.

Speaker 2 In ancient times, homosexual relationships were extremely common, but being quote-unquote gay wasn't really an identity.

Speaker 2 In Roman society, bisexuality was quite normal among the upper classes especially.

Speaker 2 As we've seen in past episodes, famous Romans like Julius Caesar, Mark Anthony, and Nero were all known to have both male and female lovers.

Speaker 2 For the pagan Romans, there was nothing immoral about homosexual sex, unless, of course, you were the passive partner in the exchange.

Speaker 2 There was absolutely nothing wrong with penetrating, but being penetrated, on the other hand, was seen as shameful for a man.

Speaker 2 In ancient Rome, if there was a nasty sexual rumor about you, it was usually that you had allowed yourself to be penetrated.

Speaker 2 There was nothing wrong with same-sex couplings so long as you were on what was considered to be the correct end of things.

Speaker 2 In Rome, there was also the social convention that your homosexual relationships remained somewhat discreet, and you presented as predominantly hetero in public.

Speaker 2 Hadrian apparently had little time for this. His political marriage to Sabina was famously unhappy and never produced any children.

Speaker 2 There's even a chance that their marriage went completely unconsummated, such was Hadrian's total distaste for heterosexual sex.

Speaker 2 As Hadrian settled into his role as emperor, he became less concerned with presenting as adequately interested in female companionship.

Speaker 2 He simply stopped hiding his relationships with other men and teenage boys, and in fact, started celebrating them.

Speaker 2 Even for the permissive Romans, this was seen as pushing the boundaries of what was acceptable.

Speaker 2 Now, to most open-minded people in 2018, the fact that Hadrian was gay and was having relationships with other men isn't really an issue.

Speaker 2 But what rankles the modern observer was that he was having relationships with people that we would consider to be underage.

Speaker 2 This is understandably a huge taboo in our society, and rightfully so. I really don't want anyone coming away from this episode thinking I'm somehow advocating for relationships with young teenagers.

Speaker 2 My career as a teacher would be over.

Speaker 2 But it's important that we understand that the ancients had a very different understanding of these types of relationships, especially the Greeks.

Speaker 2 In ancient Greece, there was a type of institutionalized pederasty among the upper classes.

Speaker 2 It was common for an older man, usually in his 30s or 40s, to have a relationship with a young teenage boy who was between the ages of 13 and 17.

Speaker 2 This was both a sexual relationship as well as a type of mentorship.

Speaker 2 The older partner was expected to see to his younger partner's education and help him develop into a functional member of the upper crust.

Speaker 2 Obviously, this seems completely wrong by modern standards, but in the ancient world, it was a thing.

Speaker 2

Hopefully, this helps put Hadrian's relationships into some sort of context. To the Romans, his relationships weren't considered criminal or even without precedent.

They just seemed overly Greek.

Speaker 2 Just like everything else about the emperor, all of his tastes were just a touch too Greek for the Romans.

Speaker 2 This finally brings us to Antinous,

Speaker 2 Hadrian's most famous teenage lover.

Speaker 2 When we factor Antinous into the equation, what should we think about Hadrian?

Speaker 2 The youth known to history simply as Antinous has a biography that is as hazy as they come.

Speaker 2 Perhaps the best reconstruction of Antinous's story comes from the historian Royston Lambert in his book, Beloved and God, the story of Hadrian and Antinous.

Speaker 2 Lambert's conclusions have really guided me in this podcast, so if you want to go deeper, then that's not a bad place to start.

Speaker 2 As far as we can tell, Antinous was born in the Roman province of Bithynia, in what is today Turkey, sometime around 110 AD.

Speaker 2 He appears to have been the son of poor, but freeborn, ethnically Greek provincials.

Speaker 2 Despite the insistence of later accounts, Lambert and other historians believe that Antinous was not a slave, but instead just very poor.

Speaker 2 He first met the Emperor Hadrian in 123 AD, when he would have been around 13 years old, and the emperor would have been around 48.

Speaker 2 He was most likely presented to the emperor as a beautiful youth worthy of his attention and affection. When you're a Roman emperor, people just kind of hook that stuff up for you.

Speaker 2 Now, while it's likely that their sexual relationship began right away, Lambert believes that it may not have.

Speaker 2 Hadrian had Antinous sent to Italy, where the young man was to be educated.

Speaker 2 It was sometime within the next few years, when Hadrian eventually returned to the peninsula, that Antinous became his favorite.

Speaker 2 Hadrian seems to have been taken not only by the boy's physical appearance, but also his intelligence and a wisdom that was said to be well beyond his years.

Speaker 2 We do know that when Hadrian departed again for Greece in 124, Antinous was with him and part of his personal retinue. This is when Hadrian's infatuation with the young man really began.

Speaker 2 According to Lambert, Hadrian would become exceedingly isolated and lonely as his reign progressed.

Speaker 2 As strange as it may sound, this teenage boy seems to have been one of the few people who actually connected with Hadrian on a personal and emotional level.

Speaker 2 Lambert would write this about their relationship: quote,

Speaker 2 The way Hadrian took the boy on his travels, kept close to him at moments of spiritual, moral, or physical exaltation, and, after his death, surrounded himself with his images, shows an obsessive craving for his presence, a mystical, religious need for his companionship.

Speaker 2 End quote.

Speaker 2 Antinous would become one of Hadrian's most essential travel companions.

Speaker 2 As I mentioned earlier, the Romans would have viewed this relationship not as sinful, but as a little indulgent and far too Greek.

Speaker 2 Even in Greece, where relationships such as these were more socially acceptable, discretion was always key.

Speaker 2 One was not supposed to openly flaunt or advertise their their sexual relationship with a younger man. You had to be cool about it.

Speaker 2 The Emperor Hadrian, on the other hand, was putting it right out there and was actively publicizing his and Antinous's adventures together.

Speaker 2 There was a particularly notable incident that occurred while Hadrian and Antinous were visiting the North African province of Libya.

Speaker 2 Apparently, the emperor was informed that a man-eating lion had been menacing the local population.

Speaker 2 The emperor, who was an avid hunter, decided that he and Antinous were going to hunt down this lion themselves.

Speaker 2 We're told that the two men headed out into the Libyan wilderness searching for the lion. They eventually found the beast, which promptly attacked them.

Speaker 2 The story goes that Antinous was very nearly mauled to death by the lion before Hadrian heroically saved his young lover and killed the beast once and for all.

Speaker 2 Hadrian apparently took so much pride in this little incident that he wanted to share this exploit with the entire empire.

Speaker 2 He had special coins pressed to commemorate the moment and even had a special circular carving known as a tondo created to celebrate the great lion hunt.

Speaker 2 This tondo was even added to a triumphal arch in Rome.

Speaker 2 Now,

Speaker 2 did this moment ever actually happen?

Speaker 2

On the one hand, it feels like a bit of imperial propaganda. Emperor kills lions single-handedly.

Kind of reminds me of Vladimir Putin bare-chested on a horse.

Speaker 2 There is a very good chance that this story was exaggerated, but the sources seem to agree that it did happen.

Speaker 2 I know it smells like a historical myth, but I mean, when the sources all tell you that it happened, I mean, what do you do?

Speaker 2 What's perhaps even more significant is that Antinous was such an important part of the tale.

Speaker 2 Whether or not the lion hunt was exaggerated, it's clear that Hadrian wanted the whole empire to celebrate their exploits together.

Speaker 2 The other notable thing about the depictions of this particular event is that Antinous is depicted as notably older and less boyish.

Speaker 2 By this time, the young man was probably around 18 years old, and was looking decidedly more mature. That is, of course, if we can trust the coins and the tondo.

Speaker 2 I bring this up because it may have played a part in the tragedy that is about to strike.

Speaker 2 In the year 130, Hadrian, Antinous, and their entourage gathered in Egypt and set out on a cruise along the Nile River. By the time this trip was over, Antinous

Speaker 2 was dead.

Speaker 2 So,

Speaker 2 what happened?

Speaker 2 Well, the most obvious and least interesting explanation was that the whole thing was a tragic accident.

Speaker 2 Antinous either went for a swim or fell off the boat they were traveling on and got caught in the strong current of the Nile and drowned. Simple as that.

Speaker 2 In many ways, this is the most most clean explanation for what happened, and many historians stop right there. They think that it was just an accident.

Speaker 2 But Royston Lambert points out that in all of the official statements put out by Hadrian about the death of Antinous, he never once explicitly states that the death was an accident.

Speaker 2

Lambert has commented that this is a little suspicious. And honestly, I'm kind of inclined to agree with him.

If it was an accident, then why not just say it was an accident?

Speaker 2 So now we get into the theories.

Speaker 2 The first theory is that Antinous killed himself.

Speaker 2 He was getting older, and perhaps he was becoming worried that the Emperor Hadrian would grow bored of him once he no longer had the glow of youth about him.

Speaker 2 So, in a fit of jealousy and despair, he threw himself overboard. This theory is supported by the fact that a new teenage aristocrat named Lucius had joined the entourage.

Speaker 2 The theory goes that Antinous was threatened by this new rival for Hadrian's affections.

Speaker 2 The weakness of this theory is that it's almost entirely conjecture.

Speaker 2 There's no supporting evidence that suggests that Antinous was the jealous type, and his influence on the emperor seems to have been minimal to non-existent.

Speaker 2 The suicide theory kind of comes out of nowhere.

Speaker 2 The next theory is that Antinous died during a ritual castration gone wrong. This would have been done in an attempt to keep him forever youthful.

Speaker 2 Perhaps the procedure was botched, and the unfortunate Antinous died.

Speaker 2 This one is interesting, but the problem with it is Antinous's age. By this point, he was probably 18 and on the other side of puberty.

Speaker 2 As such, the castration would not have achieved its intended purpose. So, why even do it?

Speaker 2 The final theory, and perhaps the most interesting, was first popularized by the historian Cassius Dio, some 80 years after the fact. As we've seen, Dio was a bit of a Hadrian skeptic.

Speaker 2 Now he reports that Antinous died as the result of an elaborate human sacrifice ritual.

Speaker 2 The story goes that Hadrian had been dealing with health issues in the months leading up to the trip through Egypt.

Speaker 2 While there, he learned of a sacred ritual that could restore life and virility to the old. The only catch was that someone young and healthy had to die in their place.

Speaker 2 In some tellings, Hadrian forced Antinous to sacrifice himself. In others, Antinous bravely volunteered to give his life in order to save the emperor.

Speaker 2 This is a very compelling theory.

Speaker 2 Not only does it have the support of Cassius Dio, but it fits with some other things we know about Hadrian, Namely, that he was a devotee of Eastern mystery cults, including the famous Elysian Mysteries.

Speaker 2 But, and there is a big butt here, Hadrian also famously abhorred the practice of human sacrifice, and worked hard to have it snuffed out across the empire.

Speaker 2 So

Speaker 2 there really is no clear answer. I personally like the last theory,

Speaker 2 but there's also a part of me that kind of knows that Antinous probably just drowned.

Speaker 2 But I could believe that Hadrian could be talked into just one human sacrifice if he believed it was for the greater good of the empire.

Speaker 2 After all, if Antinous's death was an accident, then why not say so?

Speaker 2 What isn't ambiguous was Hadrian's reaction to the death of his young lover. He grieved loudly and publicly.

Speaker 2 Multiple sources speak of him weeping uncontrollably, and then, almost immediately, he has Antinous

Speaker 2 made a god.

Speaker 2 While he was still in Egypt, he had the Egyptian priests make Antinous part of the cult of Osiris.

Speaker 2 Hadrian had a new temple city founded at the site of Antinous's death and named it, what else, Antinuopolis. Upon returning to Rome, he had the Senate officially deify the young man.

Speaker 2 Antinous would become the patron deity for youthful beauty. And amazingly, his cult really caught on, especially in the Eastern Empire.

Speaker 2 Statues to the deified Antinous sprouted up across the Roman world, and he was worshipped as a love god.

Speaker 2 At one point, his cult cult even rivaled in popularity the rising religion based around some crucified Judean carpenter.

Speaker 2 Antinous became a myth.

Speaker 2 Did Hadrian deify the young man simply out of grease and a sense of loss? Or did he do it because he felt responsible for his death?

Speaker 2

Again, there's no way to know for sure. In my mind, the narrative that Antinous sacrificed himself for the emperor makes for the neatest arithmetic.

But human beings are endlessly complicated.

Speaker 2 If I've learned nothing else from this podcast, it's that just because something makes a nice and neat story does not necessarily mean that it's true.

Speaker 2 So, in the end, how should we judge the Emperor Hadrian? Was he a good emperor or a bad emperor? An admirable patron of the classical world or a murderous pedophile?

Speaker 2 He may have been all of these things in turns. It all depends upon which metric you use to judge him.

Speaker 2 To many of his contemporaries and to ancient historians like Cassius Dio, he was an okay emperor with somewhat scandalous personal tastes.

Speaker 2 His rise to power, love of all things Greek, distaste for the eternal city, defensive foreign policy, and overly public homosexuality made him, well, maybe not evil like Nero or Caligula, but weird to the ancient Romans.

Speaker 2 On the other hand, Renaissance and Enlightenment era historians like Machiavelli and Gibbon saw him as unambiguously great.

Speaker 2 These historians saw the health of empire as the highest good.

Speaker 2 In Hadrian, they saw an intelligent, philosophically minded man who made unpopular but ultimately good choices for the empire. To them, he was a philosopher king and a bit of a Renaissance man.

Speaker 2 He kept the empire strong and ensured that its golden age would last until the end of the century. He ruled well, and for them, that made him a quote-unquote good emperor if not one of the best

Speaker 2 but how about us sitting here in 2018 how should we feel about Hadrian can we judge an ancient person by the standards of our own time or should we judge them in the context of their particular historical era

Speaker 2 Hadrian is challenging no matter how you slice that cake if we use ancient standards then he was bad because he moved Terminus' boundary and his homosexuality wasn't the right kind of homosexuality.

Speaker 2

But of course, that doesn't feel quite right. If we use modern standards, then he was a pedophile.

Plain and simple. He liked sleeping with young teenagers.

Speaker 2 But it also feels strange to condemn someone for a practice that was largely seen as acceptable by many ancients, especially in the Greek parts of the empire.

Speaker 2 It's a funny thing judging historical figures. We often don't end up judging them by the standards of either our time

Speaker 2 or their own time.

Speaker 2 Hadrian is only good if you take the long view of history and subtract what the naysayers of his day said about him.

Speaker 2 But ironically, if we start using modern standards to judge him, then his relationships with people we would consider to be minors becomes inexcusable, not to mention a potential murder.

Speaker 2 I think the truth of the matter is that people can contain multitudes. Hadrian was an impressive administrator with a truly great vision for the empire.

Speaker 2 He was also a petulant know-it-all who snubbed his nose at Roman traditions.

Speaker 2 He also helped encourage an era of building and learning across the Mediterranean world and ushered in a new high watermark for civilization.

Speaker 2 He also maybe murdered a kid who he liked to have sex with. I didn't even get a chance to tell you what Jewish sources think of Hadrian.

Speaker 2 His arguably genocidal treatment of them during the Third Jewish War led to the convention of Jews saying, May his bones be crushed, every time Hadrian's name was said out loud.

Speaker 2 Human beings, especially human beings who impact history in dramatic ways, are rarely all good or all bad. Anyone who tells you different is probably peddling some fake history.

Speaker 2 Okay,

Speaker 2 that's all for this week. Thanks again for joining us for the beginning of season four of Our Fake History.

Speaker 2

If you're interested in that opera I was talking about, it is running at the Canadian Opera Company here in Toronto from October 13th to October 27th. It looks really cool.

It's called Hadrian.

Speaker 2 Once again, it's Rufus Wainwright composing and the libretto by Daniel McIver. If you want to learn more about it, go to www.coc.ca.

Speaker 2

Before we go this week, I also have some big announcements. So while I was away for the break, you lovely people were awesome and you helped us hit our Patreon goal.

We did it.

Speaker 2 We hit our second ever Patreon goal.

Speaker 2 It's very exciting because it means that the patrons now get their promised gift and that gift is a brand new extra episode that is just for them.

Speaker 2 I'm not going to sell this one anywhere else, I have decided. This one is going to be 100% just for those of you supporting on Patreon.

Speaker 2 Now, I've already gotten a bunch of great suggestions for possible topics. So, in the coming week or so, I am going to put up a poll on the Patreon site.

Speaker 2 That's patreon.com/slash/ourfakehistory, where you will be allowed to vote on the top five suggestions that I liked the best. So I know it's not like a perfect democracy.

Speaker 2 I do get to, you know, throw my weight around a bit here. But once I've picked my top five, then all of you get to vote and then I will honor your decision of which of those topics you want me to do.

Speaker 2

I will then start researching that topic and I will create an extra episode. I don't know how long that will take me.

Hopefully just a few months to get it all put together.

Speaker 2 And the goal is to have it to you around around the holidays. Wouldn't that be a nice

Speaker 2 gift?

Speaker 2 So if you're curious about joining Patreon, and honestly, it's a really good time to do it because if you join now, you'll get an opportunity to vote on the extra episode, then just go to patreon.com slash our fake history and look at the different levels of support.

Speaker 2 Now, while I'm talking about Patreon, I need to give some huge shout-outs because there were so many people who pledged over the summer. So here come some names.

Speaker 2 I hope you're listening out there, you awesome Patreon supporters. So, today I'm giving a shout-out to

Speaker 2 Damian Mankoff, Sam Atkinson, Mr. Pikes, James Grenier, Jared Reed, Sean Matchet,

Speaker 2

Brian S. Rowe, Mikel Sequeland.

Oh, I hope I got that one right. John Kerr.

Hey, buddy, John Kerr, I know you.

Speaker 2 Rudy Ruling, Osi Rajala, Matthew Ambrogi, Ian Slinkman, Joe Baranek, Alexandra Stratcotter,

Speaker 2

Laura Alfegeme Schmidt. Ooh, that's another tricky one.

Alphageme Schmidt, Aaron W.

Speaker 2 Peter Lundblad,

Speaker 2 and James Jarvis. So all of you have decided to support the show at the $5

Speaker 2 or more level.

Speaker 2 That makes you really beautiful people.

Speaker 2

Honestly, I am overjoyed that we hit our goal. Every time we hit a goal, it just means that I get a step closer to making podcasting my full-time job.

I absolutely love teaching, don't get me wrong.

Speaker 2 But

Speaker 2 wouldn't it be cool if all I did was make Our Fake History and other podcasts?

Speaker 2 So you guys are helping that dream come true.

Speaker 2 I've got a crazy year coming up in my life. I might be giving you more life updates

Speaker 2 in the coming months.

Speaker 2 But yeah, I got some big changes coming down the pipe for me. And so you folks supporting my life

Speaker 2 means a lot. So I want to give back to you, and I really hope that you like the upcoming extra episode that we're going to create after you all go and vote.

Speaker 2 All right, I've talked for far too long today.

Speaker 2 Let's wrap it up.

Speaker 2 As always, the music for the show, the theme music, comes to us from Dirty Church. You can check out Dirty Church at dirtychurch.bandcamp.com.

Speaker 2 And all the other music that you heard on the show today was written and recorded by me.

Speaker 2 My name is Sebastian Major. And remember, just because it didn't happen doesn't mean it isn't real.

Speaker 2 One, two, three, five.

Speaker 2 There's nothing better than a one-play side.