Episode #216 - Did the Siege of Constantinople Even Happen? (Part I)

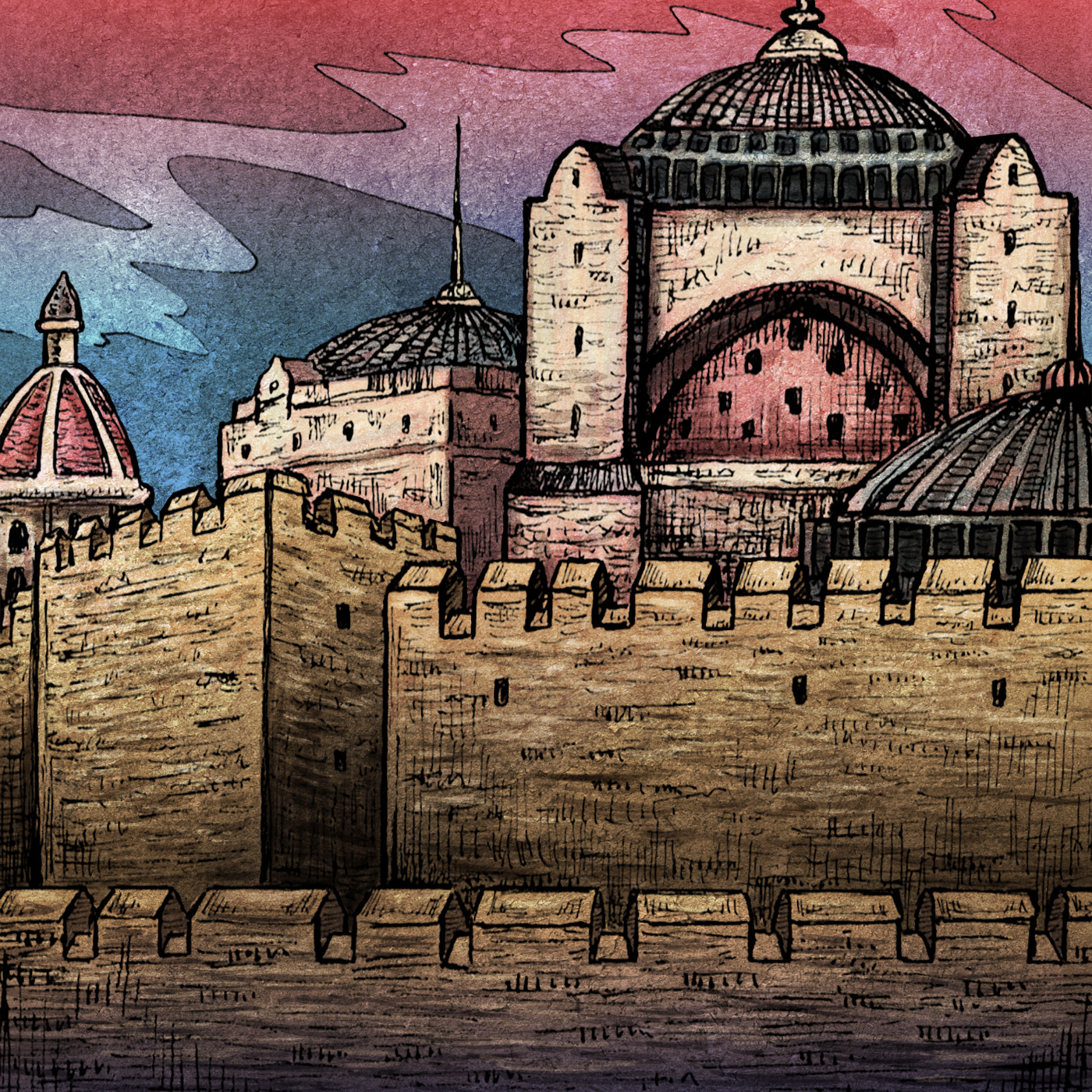

When the capital of the Roman empire was moved from Rome to the city of Constantinople, the city on the Bosporus strait became one of the most important places on planet earth. One top being the heart of Roman religious, political, and cultural life for a millennium, the city had a reputation for being impregnable. From the 6th to the 13th century the city was besieged an amazing 19 times, and not once was it overcome by a foreign army. This resilience added to the city's legendary status. Two of the most significant sieges came at the hands of the Muslim Umayyad Caliphate, in 674 and 717. These battles have been cited as historical turning points, however recent scholarship has cast doubt on the traditional sources. How significant were these sieges? Did they both even occur? Tune-in and find out how sassy Voltaire, sloppy meta-narratives, and the end of the world all play a role in the story.

See Privacy Policy at https://art19.com/privacy and California Privacy Notice at https://art19.com/privacy#do-not-sell-my-info.

See Privacy Policy at https://art19.com/privacy and California Privacy Notice at https://art19.com/privacy#do-not-sell-my-info.

Press play and read along

Transcript

Transcript is processing—check back soon.

Our Fake History — Episode #216 - Did the Siege of Constantinople Even Happen? (Part I)