The Rise of Techno-Authoritarianism

Want to share unlimited access to The Atlantic with your loved ones? Give a gift today at theatlantic.com/podgift. For a limited time, select new subscriptions will come with the bold Atlantic tote bag as a free holiday bonus.

Learn more about your ad choices. Visit megaphone.fm/adchoices

Press play and read along

Transcript

Speaker 1 Take the next 30 seconds to invest in yourself with Vanguard.

Speaker 2 Breathe in.

Speaker 1

Center your mind. Recognize the power you have to direct your financial future.

Feel the freedom that comes with reaching your goals and building a life you love.

Speaker 1

Vanguard brings you this meditation because we invest where it matters most in you. Visit vanguard.com/slash investinginyou to learn more.

All investing is subject to risk.

Speaker 3 How does PWC take your company to the leading edge? They bring the sharpest minds in tech to your team so you can bring the ideas that will transform your business.

Speaker 3 They're passionate about your industry, so you can walk into any room with every advantage. And they're with you every step of the way, so you can know you're headed in the right direction.

Speaker 3 PWC builds for what's next so you can get there now. Get started at pwc.com/slash uslash leading edge.

Speaker 4 This is the big surprise in Silicon Valley today. Sam Altman, the face of the generative AI boom and CEO of OpenAI, he's out of the company.

Speaker 2 You probably remember seeing headlines right before Thanksgiving about a bunch of drama at OpenAI.

Speaker 4 That roller coaster ride at Open AI is over, at least we think it's over. Ousted CEO Sam Altman has been rehired, and the board that pushed him out is gone.

Speaker 2 I mean, it was probably the most dramatic story in tech, possibly, of this century. I mean, really dramatic.

Speaker 5 That's Adrienne LaFrance, the executive editor of The Atlantic, and she's been following tech for decades. So you would expect that she would find this Silicon Valley office gossip dramatic.

Speaker 5 But the surprising thing is, a lot of people did. Which is probably because underneath that will they or won't they rehire Sam Altman, there was a a more fundamental debate going on.

Speaker 2 On one side, you have people arguing for a more cautious approach to development of artificial intelligence.

Speaker 2

And on the other, you have an argument or sort of a worldview that says, this technology is here. It's happening.

It's changing the world already.

Speaker 2 Like, there's not only should we not slow down, but it would be irresponsible to slow down.

Speaker 2 So this just dramatically different worldview of, you know, almost polar opposites of if you slow down, you're hurting humanity versus if you don't slow down, you're hurting humanity.

Speaker 5 So the most oversimplification is like scale and profit versus caution.

Speaker 2 Exactly.

Speaker 2 But the people who are on the scale and profit side would like you to believe that they are also operating in humanity's best interest.

Speaker 5 This is Radio Atlantic.

Speaker 2 I'm Hannah Rosen.

Speaker 5 The drama at OpenAI was a rare moment where an ideological divide in Silicon Valley was so central and explicit.

Speaker 5 We're not going to talk about the Sam Altman saga today, but we are going to talk about these underlying beliefs.

Speaker 5 Because in an industry defined by inventions and IPOs and tech bro jokes, it's easy to miss what a fundamental driver ideology can be.

Speaker 5 In a recent story for The Atlantic, Adrienne argued that we should examine these views more carefully and take them much more seriously than we do.

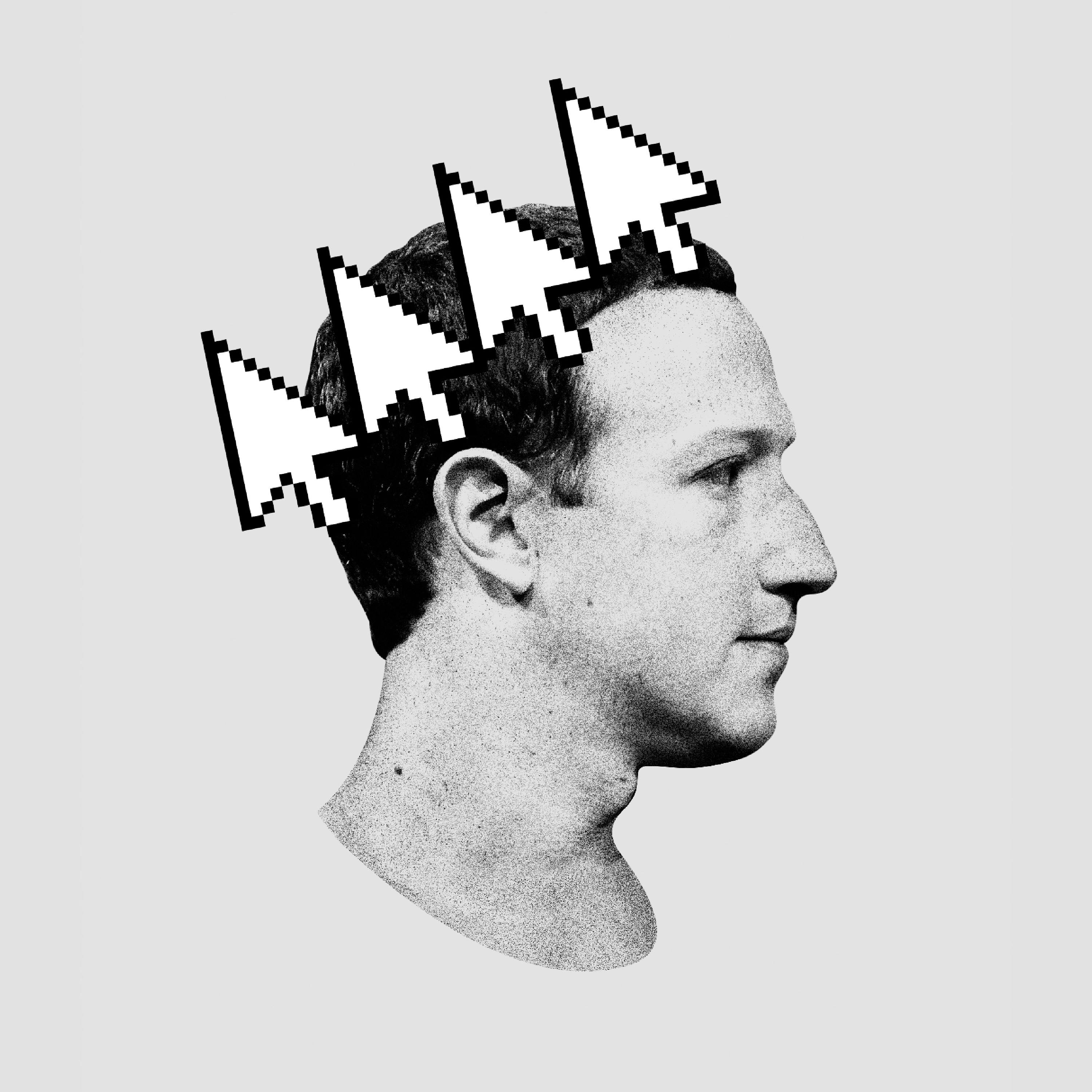

Speaker 5 And she put a name to the ideology, techno-authoritarianism.

Speaker 5 So we are used to thinking of some tech titans as villains, but you're kind of defining them as villains with political significance. What do you mean when you call them the despots of Silicon Valley?

Speaker 2 So I've been thinking about this for years, honestly, and something that had been frustrating me is I feel that we as a society haven't properly placed Silicon Valley where it needs to be in terms of its actual importance and influence.

Speaker 2 So we all know it influences our lives. And we could talk, I would love to talk about screens and social media and all the rest.

Speaker 2 But Silicon Valley has also had this profound influence politically and culturally that is much bigger than just the devices we're holding in our pockets.

Speaker 2 And it has bothered me because I feel like we haven't properly called that what it is, which is an actual ideology that comes out of Silicon Valley that is political in nature, even if it's not a political party.

Speaker 2 It's this worldview that is illiberal. It goes against democratic values, meaning, you know, not the Democratic Party, but values that promote democracy and the health of democracy.

Speaker 2 And it presupposes that the technocratic elite knows best and not the people.

Speaker 5 I mean, authoritarian is a very strong word. We're used to using authoritarian in a different context, which is our political context.

Speaker 2 Definitely. I mean, I guess the nuance I would want to add is that this is not political in the traditional sense.

Speaker 2 It's not as though you have authoritarian technocrats trying to come to power in Silicon Valley by way of elections or coups, even.

Speaker 2 They're not even bothering with our systems of government because they already have positioned themselves as more important and influential culturally.

Speaker 2 And so it's almost like they don't need to bother with government for their power.

Speaker 5 Aaron Powell, I see. So it's a form of power we don't even recognize because we don't exactly have structures to put it in or understand it.

Speaker 2 Aaron Ross Powell, well, we may not recognize it as readily because of that, but I think if you look not even that closely, it's pretty plain to see.

Speaker 2 If you just pay attention to how people talk about what they think matters, who they think should make decisions, who they characterize as their enemies, institutions, experts, journalists, for example.

Speaker 2 You know, it very, like if it looks like an authoritarian and cracks like an authoritarian, then, you know, ta-da.

Speaker 2 Right.

Speaker 2 The reason I wanted to try to define what this ideology is is I do feel as though over the past five to 10 years, something has shifted gradually at first and then more quickly that the sort of subversion of Enlightenment era language and values to justify an authoritarian technocratic worldview was was alarming to me.

Speaker 2 And so, for example, you'll see a lot of people in this category describing themselves as free speech absolutists, for example.

Speaker 2 I think a really easy example of this would be Elon Musk, and saying all the things that someone who believes in liberal democracy might agree with on its face, but then acting another way.

Speaker 2 So to say you're a free speech absolutist, but then tailor your privately run social platform to serve your own needs and beliefs and pick on your perceived enemies.

Speaker 2 I mean, that's not free speech absolutism at all. And so this sense of aggrievement has accelerated and become, you know, more vitriolic and more ostentatious.

Speaker 2 It just seems like it's getting more pronounced.

Speaker 5 When did you start paying attention to tech titans? When did you start following the industry?

Speaker 2 I first started really writing about Tech for the Atlantic in 2013.

Speaker 5 What was the promise of tech back then? How were tech Titans framing their own work or behaving differently than now?

Speaker 2

Right. I mean, so 10 to 15 years ago, we were talking about the dawn of the social mobile age.

So smartphones are still sort of new. Like, social media is not totally new.

Speaker 2

You know, Facebook started in 2004. You could go back to like Friendster or MySpace before that.

Uber was new. Like, it was very much an era of

Speaker 2 people still being

Speaker 2

wowed. And frankly, I'm still wowed by this.

Of like, you pick up this smartphone, this new, shiny, beautiful device, and you press a button on the phone, and something can happen in the real world.

Speaker 2 You summon a taxi, you know, food delivery, like all of this stuff seems totally normal to us now.

Speaker 2 But it was this miraculous time where people were creating a way of interacting with the world that was totally new.

Speaker 2 And so, there was still, I think, certainly healthy skepticism, but you had a lot of the bright-eyed optimism that I think started certainly in the 90s still carried over.

Speaker 5 And was there a worldview attached to that awe? Like I remember the phrase, don't be evil, but I can't place it in time. Like, was there some idea of...

Speaker 2 You know, that I can't remember when Google retired that, but there, there certainly came a point where it became ridiculous. to wear that optimism on your sleeve.

Speaker 2 There was this time where Silicon Valley was a place for underdogs, for people with like big dreams and and the ability to code, and they'd come and do amazing things.

Speaker 2 I think we also have to remember, I don't want to be too starry-eyed about it, because even then, this was an era where you had like the bro-ish culture and women working in a lot of these companies at the time report just like terrible experiences.

Speaker 2 And so like there are flaws from the start, as with any industry or any culture. But I think 10 or 15 years ago is around the time things started to curdle a little bit.

Speaker 2 I believe it was 2012 when Facebook eventually bought Instagram with its billion dollar valuation. And it was this moment where people were like, no, come on, like that's an insane amount of money.

Speaker 2 Is it really worth that? And you had a string of these sort of like, just like

Speaker 2 obscene amounts of money. And what you were witnessing, and I think people were starting to realize this then too, was like the

Speaker 2 monopolization, these giants gobbling up their competitors, like the forces set in motion that led us to the environment that we're in today.

Speaker 2 And we didn't know it until a couple of years later, but 2012 was also the year that Facebook was doing its now infamous mood manipulation experiments when it was showing users different things to see if they could try to make people happy or sad or angry without their consent.

Speaker 2 And by then, I think the general public was starting to realize, you know, there may be some downsides to all these shiny

Speaker 5

things. Yeah.

And then came 2016 when it felt like Facebook's role in the election was something everybody noticed.

Speaker 2 Right. And all kinds of questions about targeted ads for certain populations and election interference, foreign or otherwise.

Speaker 2 And so definitely, there was another wave of intense criticism for Facebook then. You know, serious questions about these companies wreaking havoc have been around for years.

Speaker 5 It's been eight or ten years.

Speaker 5 So, like, what feels different now?

Speaker 2 The reason I wrote this now is we are

Speaker 2 in America, certainly, and elsewhere in the world, facing a real fight for the future future of democracy. And the stakes are high.

Speaker 2 And it seemed important to me, you know, at a time when everyone's going to be focused on the 2024 presidential election as they should be, and the stakes there, there are other forces for illiberalism and autocracy that are permeating our society.

Speaker 2 And we should reckon with those too.

Speaker 5 After the break, we talk about a voice that seems to capture techno-authoritarianism perfectly. And of course, we reckon.

Speaker 6 Recently, we asked some people about sharing their New York Times accounts.

Speaker 7

My name is Kayla. My husband and I use his email address to access the New York Times each day.

We compete for who gets to do connections.

Speaker 7

Sometimes I log into the app and I discover that he's already finished connections that day. And I'm like, Jonah, it was my day.

And he's like, I know, I just couldn't resist.

Speaker 7

You would do us a huge favor if we got to log in as a family with separate emails. I really think our well-being as a couple depends on it.

Thanks for looking into this.

Speaker 2 Kayla, we heard you.

Speaker 6

Introducing the New York Times Family Subscription. One subscription, up to four separate logins for anyone in your life.

Find out more at nytimes.com/slash family.

Speaker 8

Attention, all small biz owners. At the UPS store, you can count on us to handle your packages with care.

With our certified packing experts, your packages are properly packed and protected.

Speaker 8 And with our pack and ship guarantee, when we pack it and ship it, we guarantee it because your items arrive safe or you'll be reimbursed. Visit the ups store.com/slash guarantee for full details.

Speaker 8

Most locations are independently owned. Product services, pricing, and hours of operation may vary.

See Center for Details. The UPS store.

Be unstoppable. Come into your local store today.

Speaker 2 So, if you look at the social conditions that help provoke political violence or stoke people's appetite for a strong man in charge, or pick your like destabilizing social, political, cultural force, like a lot of those things go together and overlap.

Speaker 2 And I think a lot of those same conditions are exacerbated by our relationship, individual and societal, with technology.

Speaker 2 And then further exacerbated by the tech titans who want to defend against any criticism of the current environment.

Speaker 5 I see. So the tolerance for political autocracy and our tolerance for technological autocracy, they kind of meld together and produce the same results.

Speaker 2

I think so. I mean, like, just think about Orwell or Ray Bradbury.

Like, we know that. I mean, like, okay, those were futuristic books in their times, thinking of 1984 and Fahrenheit 451.

Speaker 5 But, like, politics and technology, the interaction between that is the engine of sci-fi.

Speaker 2

Yeah. Or just look at like how Hitler used the radio.

Like technology is not inherently evil. I love technology.

I desperately love the internet. Like I actually do.

Speaker 2 But I think when you have extraordinarily powerful people

Speaker 2 putting their worldview in terms of progress is inevitable and anyone who doesn't want to just like move forward for the sake of moving forward is on the side of evil.

Speaker 2

Like just the starkness of how they frame this is so uncomplicated. There's no nuance and it's in really authoritarian terms.

Just, it should scare people.

Speaker 5 Okay, I think I want to get to the specifics of what this ideology actually is.

Speaker 2

Okay, so a useful example is Mark Andreessen, the venture capitalist. You know, Andreessen Horwitz is his firm.

He's very well known, influential, but a pugnacious guy.

Speaker 2 And he has written what he calls the techno-optimist manifesto.

Speaker 2 And it's a very long blog post, but I think a revealing one and worth reading in the sense that it lays out some of what I'm describing here.

Speaker 2 He lists sort of what a techno-optimist would believe, and I'm paraphrasing here, but progress for progress's sake, always moving forward, rejecting tradition, rejecting history, rejecting expertise, rejecting institutions.

Speaker 2 He has a list of enemies.

Speaker 2 You look at the well that people are drawing from, and it gives you a sense sense of sort of the intellectual rigidity, I would say, of just what we're doing is good because it's what we're doing and we're going to do it because we're doing it.

Speaker 2 There's sort of this like circular logic to it.

Speaker 2 So anyway, that's one example is the Techno-Optimus Manifesto.

Speaker 5 Let's read some of the lines just to typify his style of writing and thinking. I mean, the one that I always think about is the one about the lightning.

Speaker 2 It's really dramatic.

Speaker 5 I remember thinking when I read that line, I've never possibly read anything as arrogant

Speaker 2

as this. Well, but we shouldn't laugh at it because he's serious.

Do you know what I mean? Like, I.

Speaker 5 Well, let's get to that, but just so people understand the stuff. Okay.

Speaker 2

He says, I'm really not going to laugh. Okay.

He says, we believe in nature, but we also believe in overcoming nature. We are not primitives cowering in fear of the lightning bolt.

Speaker 2 We are the apex predator. The lightning works for us.

Speaker 5 The lightning works for us. Wow.

Speaker 2 That's something. Look, I get like there's a version of this that is like harnessed properly could inspire people to do spectacular things.

Speaker 2

And like there's something beautiful about great imagination and tech. That's great.

But yeah, saying the lightning works for us is a bit much.

Speaker 5 I actually have trouble understanding optimist versus pessimist. Right.

Speaker 2 Like he's so mad for an optimist.

Speaker 5 Yes, it's a combination of sort of Anne Rand speak and a kind of angry Twitter manifesto, but it is dark and apocalyptic. And I did wonder about that.

Speaker 5 Like, why is it called the techno techno-optimist? And yet it feels extremely reactionary.

Speaker 5 Like, it echoes the kind of reactionary language that you hear in some corners of the Republican Party and Trumpism. It's a little bit like make America great again, the way people talked about that.

Speaker 5 It's the most, totally, the most pessimistic political slogan that anyone's ever won with. Totally.

Speaker 2 I mean, I think you're hitting the exact point, which is they take, I'll speak just for Andreessen here.

Speaker 2 He is describing himself and this manifesto as optimistic, but in the same way that some technocrats take enlightenment values and claim to support them while saying the exact opposite of what those values actually mean.

Speaker 2

And so I think it's a subversion of meaning. It's, we're optimists, we're the good guys.

And then you read it and you're like, this is horrifying.

Speaker 2 But this isn't some like Reddit forum in the corner that only six guys are reading and agreeing with each other. These are the most powerful people on the planet.

Speaker 2 And they're hugely influential and people buy into it.

Speaker 5 Could you help me understand what's the ultimate goal of a a techno-optimist? Is it social change? Is it an attitude shift? Is it money? It's very hard to understand.

Speaker 5 Is it just scaling a company or is it cultural societal change? Like, what do you think they are after?

Speaker 2

Well, I wouldn't call it a techno-optimist. I wouldn't use that term.

But the worldview that's being expressed here, I think the goal certainly is to retain power and to maximize profit.

Speaker 2 And one of the stated goals from the manifesto is, quote, to ensure the techno-capital upward spiral continues forever.

Speaker 2 So that's clearly talking about continued enrichment for these powerful people who are already very wealthy. But, you know, they want to build new things and make a ton of money.

Speaker 5

That's the weird thing. Like it doesn't sound like a business strategy.

It sounds like a manifesto for social overhaul. And so it's hard to understand what it is.

Speaker 2 I will say, to be fair, I think this encapsulates also the people who are creating world-changing tech for good, which is happening.

Speaker 2

I mean, if you look at even in the realm of AI, we hope we haven't seen it yet, but I fully expect we will see AI that helps cure diseases. That's remarkable.

Like we should all wish for that outcome.

Speaker 2 And I hope that the people working on this are singularly focused on that kind of work.

Speaker 2 And so I think if you were to ask someone like Mark Andreessen or Elon Musk or pick your favorite technocrat, they would say, we're changing the world to make it better for humanity.

Speaker 2

We're going to go to Mars. We're going to cure disease.

And people who have this worldview may, in fact, help do that, which is fantastic. But in order to get to Mars,

Speaker 2 what's the trade-off if you're talking about this worldview?

Speaker 5 Among the leaders of major tech companies, how prevalent do you think this attitude is?

Speaker 2 It's a really good question.

Speaker 2 Honestly, there are so many tech companies. I don't feel comfortable saying that it's widespread across every, like there's so many tech companies, right

Speaker 2 but it is highly visible and vocal among many very influential leaders in tech so if you were to look at every single tech company it may not even be a majority but among the most powerful people it's highly visible and prevalent

Speaker 5 and how would you compare it with the attitudes of say the robber barons of earlier eras

Speaker 2 there is actually a great book called railroaded by the Stanford historian Richard White that is mostly about Robert Barron's, but the entire time I was reading it, I was thinking about Silicon Valley because it's a very natural comparison.

Speaker 2 You have this sort of, you know, world-changing technology that is rapidly enriching this handful of powerful men, mostly men. And this question of, you know, did railroads change America for good?

Speaker 2 Certainly, of course they did. But there are questions of monopoly and how much power any one person should hold and all the questions that come up with silk and dye too.

Speaker 2 So I think there are similarities there, but I think there are limitations to the similarities in part because I think the way that the current tech advancements are changing our lives are happening on a global scale much faster.

Speaker 2 And I don't think a lot of people properly understand that like we're still just at the beginning of figuring out what smartphones and the internet have done to us. And AI is here now.

Speaker 2 And it's like the the degree to which the world is changing is, I think, so much bigger in magnitude than it is possible to understand on a normal human timeline. Like it's just, it's, it's wild.

Speaker 2 It's way bigger than we ever had.

Speaker 5 I guess the consequences of things happening faster and in a more kind of chaotic way is that A, society doesn't have time to catch up. And so you end up being more reactionary.

Speaker 5 I mean, that's generally what happens historically. And governments don't have time to catch up because they're slow moving.

Speaker 5 So the normal slow regulations that you would put in place, there just isn't time to sort of agree on them.

Speaker 5 So you've mentioned historical roots of fascism. What do you mean by that?

Speaker 2 Well, I want to be careful because it's invoked casually and lazily. And I'm not calling technocrats of today fascists, just to be totally clear.

Speaker 2 And I don't think, for instance, that the techno optimist manifesto is a fascist document. And I don't think that it is expounding a fascist fascist worldview.

Speaker 2 But if you look at the intellectual origins of some of the ideas that this manifesto contains, you clearly will be reminded of the beginnings of fascism.

Speaker 2 So if you look to the 1930s, which is when the sort of first American technocracy movement flourished, it was happening at a time when there was this push for modernism in poetry primarily, but also art.

Speaker 2 And that had found its footing among futurists in Italy as well.

Speaker 2

And so one figure in particular comes to mind and is someone who Andreessen happens to mention as one of his patron saints of techno-optimism. It's a man named F.

T.

Speaker 2

Marinetti, who is often described as the father of futurism. He writes the Futurist Manifesto, which is worth reading totally.

I agree with Andreessen on that front.

Speaker 2 And it professes this worldview of thinking about humans' place in the machine age and everything speeding up and the beauty of the future and the possibilities.

Speaker 2 It is very techno-optimistic in nature. And 10 years later, Marinetti then writes the Fascist Manifesto and many of the figures who led the futurism movement in Italy helped start fascism in Italy.

Speaker 2 You know, I'm not suggesting that this turns into fascism, but I am pointing to evidence that shows that a movement that's cultural can have huge political power when stoked by the right social conditions and charismatic leaders.

Speaker 5 Right. So a movement that has its origins in creativity and imagination can eventually kind of curdle, be manipulated into

Speaker 5 a movement where the people who have the creativity and imagination are A virtuous and B the natural leaders of a society. And then that can turn and become fascistic.

Speaker 2

Right. And just because someone says they're devoting their life or their worldview to progress, it sounds good.

Or they're an optimist, it sounds good, doesn't mean it is good.

Speaker 5 Right.

Speaker 5 Okay, you've mentioned there are good things about technology, and to be sure there are wonderful things happening. So I want to try and piece some of this apart.

Speaker 5 Andreessen talks a lot about AI risk, like it's developed into a cult. All we ever talk about is AI risk.

Speaker 5 I think there is a legitimate critique that both political parties often only see technology as dangers and, in fact, don't rely enough or encourage enough technological fixes to obvious problems that exist.

Speaker 2 What do you think about that? I love technology and agree with you, just to be clear.

Speaker 5 I mean, like I was thinking, climate change is an example. Like a lot of people would say we were too risk averse.

Speaker 5 We didn't, by we, I mean the American government did not create regulations to encourage technological innovation. We're sort of slow on that.

Speaker 5 We have build back better and it's like we have these sort of old infrastructure ideas about how to improve society when we could have encouraged a lot more technological innovations.

Speaker 2 Right.

Speaker 2 Like, well, one thing I think about a lot is Sam Altman, the CEO of OpenAI, something he said to our colleague Ross Anderson last spring, which was, you know, in a functional society, government would be doing this work that I'm doing at OpenAI, but we don't have a functional government.

Speaker 2 Basically, I'm paraphrasing what he said.

Speaker 2 You know, I think this should be the work as it was in, you know, the mid-20th century, that the great scientific innovation should be happening with public funding, with

Speaker 2 whatever degree of regulation is deemed necessary by the public.

Speaker 5 Like an NIH equivalent, basically.

Speaker 2 Yeah, or even at a university. Like universities aren't leading the way here, which is tragic,

Speaker 2 I think.

Speaker 5 I imagine if I had asked you this 10 years ago, like what government regulation should be in place? What kind of controls would you have wanted?

Speaker 5 You might have said none because you just got your new smartphone or something.

Speaker 5 How do you think about this now?

Speaker 2

I'm reluctant to talk about regulation for two reasons. One, it's so boring, Hannah.

Come on.

Speaker 2 And two, I really am not an expert on regulation. And I will confess that I don't think it's the swiftest path to the solution that's best for the people in many cases.

Speaker 2 Like, I'm not like blanket against regulation. Like, I see all the many things.

Speaker 5 I mean, I think with regulation, it's like good regulation is good, bad regulation is good. It's obstructive, like it's a case-by-case basis.

Speaker 2 100%. And the other thing is, though, that we do have some test cases.

Speaker 2 Like, if you look at some of the European or elsewhere regulation of social media, for example, it's not, I don't think, necessarily good for the public's right to know things or free speech, for example.

Speaker 2 Like a lot of what's happened in other countries would never withstand scrutiny of, you know, in terms of free speech challenges.

Speaker 5 Aaron Powell, Jr.: So what's the ultimate value you're trying to preserve?

Speaker 2 You know, maybe this is me being an optimist, but I think we have more power and agency to change the culture than it sometimes feels like. And

Speaker 2 certainly there are areas where it's really hard norms are already established. But like we should live in a world where we control how we use tech and how tech is used against us.

Speaker 2 And there's a lot of lip service paid to that idea, of course, by people in Silicon Valley who are making a ton of money off of holding people captive to their devices.

Speaker 2 But if enough smart people take ownership of this as a thing to solve and like are leaders in their communities, in their families, in their workplaces, wherever it may be,

Speaker 2 I have way more faith in individual people than the government to regulate. Although regulation is probably also important.

Speaker 5

It's interesting. We always wind up in this place.

I just came to mind the image. I met two, actually, but one very lovely 19-year-old who has a flip phone.

Speaker 2 And adorable.

Speaker 5 And then another one who has a flip phone. But that's exactly, I'm thinking, oh, that like adorable kid with his flip phone.

Speaker 2 It was like somehow like hipsters buying record players in 2010.

Speaker 5

Exactly like that. And they have to somehow like hold the barrier against meta.

It's like, it's like, it's like this young kid.

Speaker 2 Well, I mean, the power of teenagers declaring what's cool is actually hugely influential cultural force. So like teens, if you're listening, save us.

Speaker 5 Yeah, go buy some flip phones.

Speaker 5 Okay, well, we'll have to dedicate another episode to actual solutions.

Speaker 2

Perfect. I'll be there.

All right.

Speaker 5 Thank you for joining us.

Speaker 2 Thanks so much for having me.

Speaker 5 This episode of Radio Atlantic was produced by Kevin Townsend. It was edited by Claudina Bade, fact-checked by Von Kim, and engineered by Rob Smersiak.

Speaker 5 Claudina Bade is the executive producer for Atlantic Audio, and Andrea Valdez is our managing editor.

Speaker 2 I'm Hanna Rosen.

Speaker 5 Thank you for listening.

Speaker 2 Techno-authoritarianism.

Speaker 5

Boy, that's a mouthful. Techno-authoritarianism.

Techno-authoritarianism.

Speaker 2 Techno-authoritarianism.