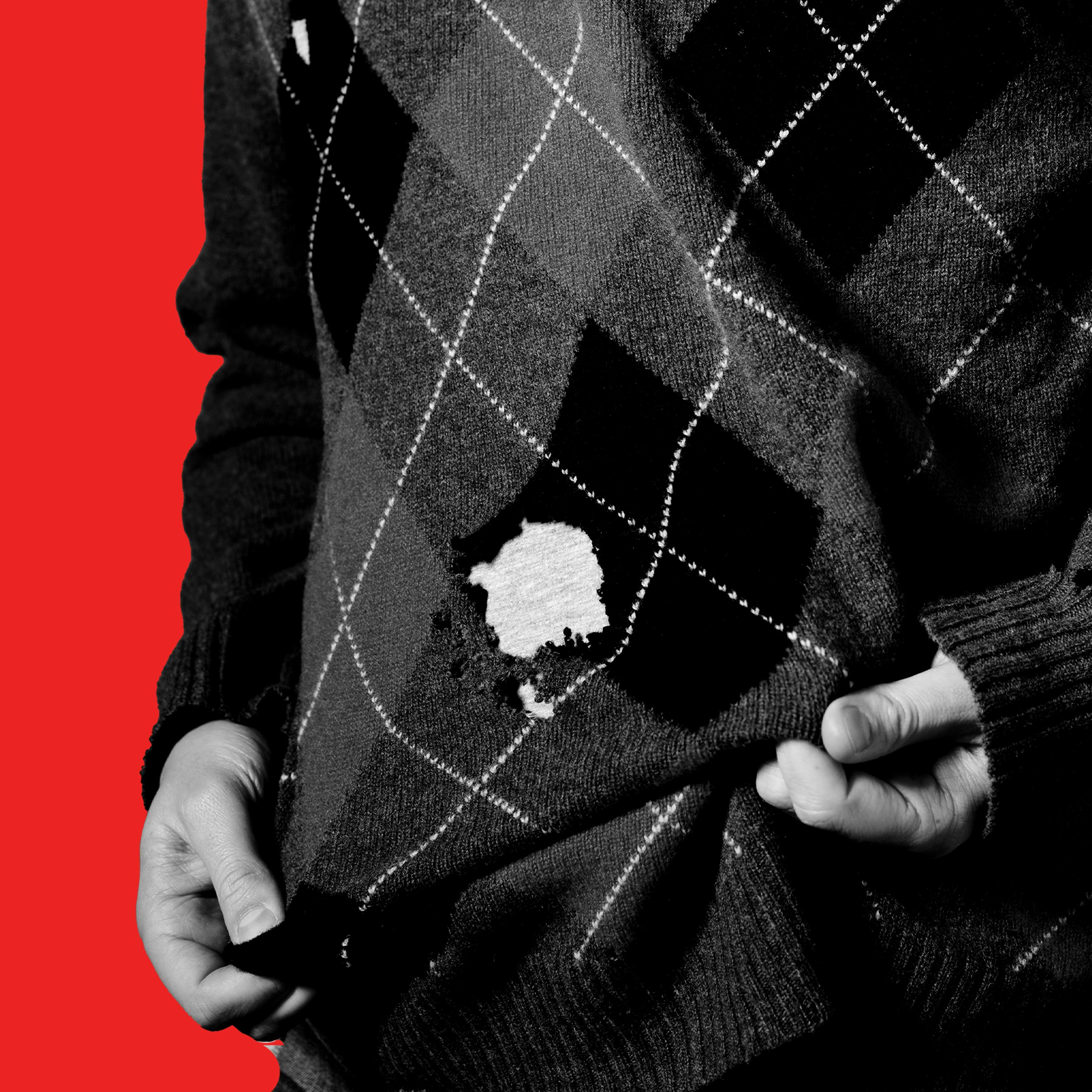

Don’t Buy That Sweater

In this episode, Hanna talks with Amanda Mull—who writes the Atlantic column “Material World”—about why so many consumer goods have declined in quality over the last two decades. As always, Mull illuminates the stories the fashion world works hard to obscure, about the quality of fabrics, the nature of working conditions, and about how to subvert a system that wants you to keep buying more. “I have but one human body,” she says. “I can only wear so many sweaters.”

Want to share unlimited access to The Atlantic with your loved ones? Give a gift today at theatlantic.com/podgift. For a limited time, select new subscriptions will come with the bold Atlantic tote bag as a free holiday bonus.

Learn more about your ad choices. Visit megaphone.fm/adchoices

Press play and read along

Transcript

Speaker 1 a business means I wear lots of hats. Luckily, when it's time to put on my hiring hat, I can count on LinkedIn to make it easy.

Speaker 1

I can post a job for free or pay to promote it and get three times more qualified candidates. Imagine finding your next great hire in 24 hours.

86% of small businesses do.

Speaker 1

With LinkedIn, I can also easily share my job with my network. No other job site lets me do that.

Post your free job at linkedin.com/slash achieve. That's linkedin.com/slash achieve.

Speaker 1 Terms and conditions apply.

Speaker 2

Tires matter. They're the only part of your vehicle that touches the road.

Tread confidently with new tires from Tire Rack.

Speaker 2 Whether you're looking for expert recommendations or know exactly what you want, Tire Rack makes it easy.

Speaker 2 Fast, free shipping, free road hazard protection, convenient installation options, and the best selection of hand-cooked tires.

Speaker 2

Go to tire rack.com to see their hand-cooked test results, tire ratings, and reviews. And be sure to check out all the special offers.

TireRack.com, the way tire buying should be. be.

Speaker 3

When it started to get pretty cold, I opened up the drawer where I keep all my sweaters. I have so many sweaters in there.

And you know what? I hate all of them.

Speaker 3

Even the ones that are supposed to be ugly. Now, because I was looking at my own closet in my own bedroom, I figured this was my problem.

I was just in my own private hell.

Speaker 3 Until I saw the headline, your sweaters are garbage. It was an article by staff writer Amanda Moll, who writes the magazine's Material World column and who is my guru of consumer dilemmas.

Speaker 3 Now, Amanda had done her own thorough sweater investigation. which was inspired by Nora Efron's great love letter to cold weather in New York City when Harry met Sally.

Speaker 3 For sweater lovers, this movie holds a special place, and it has to do with this one enduring image in the movie.

Speaker 4 Billy Crystal is in his new single guy apartment, squatting in front of one of the big windows in that apartment, and he is wearing, you know, 80s jeans and a really beautiful cabled ivory fisherman sweater.

Speaker 4

And the sweater is like, it's incredible. It's really lush.

It's really like oversized in the right ways. It is a great, great sweater.

Speaker 3 Recently, actor Ben Schwartz recreated the photo on his Instagram.

Speaker 4 And he was wearing jeans and in front of a window and, you know, ivory cabled fisherman sweater. But it was just like the sweater didn't have the juice.

Speaker 3 I'm Hannah Rosen, and this is Radio Atlantic.

Speaker 3 A comedian named Ellery Smith retweeted those two sweater pictures side by side, the one of Billy Crystal and the one of Ben Schwartz, writing, quote, the quality of sweaters has declined so greatly in the last 20 years that I think it genuinely necessitates a national conversation.

Speaker 3 I 100% agree. And the only person I want to have that conversation with is Amanda Moll, because she'll be able to explain why a sweater is not just a sweater.

Speaker 3 It's a window into so many of the problems of our modern consumer culture.

Speaker 4 So here we go.

Speaker 3 Did you yourself go through a prolonged period of sweater disappointment?

Speaker 4

You know, I moved to New York in 2011. I'm from the South.

I'm from Atlanta. So I didn't need any sweater buying skills for the first 25 years of my life.

Speaker 4 I had thought about this like not a single time because, you know, you put on a hoodie and you keep it moving where I'm from.

Speaker 4 But suddenly I needed to figure out how to buy like a whole new like cold weather wardrobe.

Speaker 4 So I made a lot of mistakes and I made a lot of sweater mistakes because I figured, you know, just go to any of the retailers where I'm buying my other stuff and order some sweaters from them and it'll be fine.

Speaker 4

It was not fine. I got a lot of like very itchy, very plasticky sweaters.

I got things that peeled up immediately that just like looked terrible, looked really cheap.

Speaker 4

Like I felt like a baked potato wrapped in foil inside of them. I was like, I was steaming like a dumpling.

I was unhappy. I was itchy.

I looked like I was in like this weird plastic material.

Speaker 4

I hated it. And I did this for years before I realized that it's the materials.

I need to be looking at the fabric labels.

Speaker 4 I need to be looking at what these sweaters are actually made out of and like probably spending some more money and spending some more time looking for better things.

Speaker 4 But yeah, I screwed up in that way for the better part of a decade, I would say.

Speaker 3 Okay, so we have sweaters of your and sweaters now. Can you walk us through how these come into the world differently?

Speaker 4 When you look at Billy Crystal's sweater, you can make a few assumptions about what's going on with it. The first thing is it's almost certainly fully wool.

Speaker 4 What kind of wool, it's impossible for me to say, but there is an almost 100% chance that what you're looking at is a completely natural fiber sweater.

Speaker 4 And it's also double-knit, which is why it looks so much heftier. At the time, sweaters were much more likely to be made of not just like natural fibers, but of 100% wool.

Speaker 4 That is traditionally the material that sweaters sweaters have been made out of for hundreds of years. A sweater like that would almost certainly be made in a wool-producing country.

Speaker 4 So it might have been made in the United States. It might have been made in Scotland, New Zealand, Ireland.

Speaker 4 One of the places in the world where a lot of sheep are raised, a lot of yarn is manufactured, and then sweaters are then made from that yarn.

Speaker 4 Because it was like almost certainly sold in the United States, in the 1980s, there were some import controls on what could be brought brought into the U.S.

Speaker 4 and sold as far as textiles go, which means it was almost certainly made in a relatively wealthy country where garment workers are more likely to have significant tenure on the job, real skills training, good wages, things like that.

Speaker 4 So it was probably made by someone who has a lot of experience making sweaters, by someone who has lots and lots of training, lots and lots of particular skills.

Speaker 3 So the yarn would be wool and whoever created it would be someone with sweater skills.

Speaker 4 Right. Making this kind of knitwear is a very, very highly skilled task.

Speaker 4 It wouldn't just be a person overseeing the machine, it would be a person manipulating the machine to ensure that you get all of that really rich cabling and all of those details.

Speaker 4 You know, it takes a lot of yarn to make a sweater that robust.

Speaker 3 So I'm kind of sweating listening to you. Like, I want to be, you know, falling into nostalgia with you, but what I'm actually thinking is like, no,

Speaker 3

no, like I feel too hot and sweaty. So, okay, so that's the sweaters of your.

Now, then what happened?

Speaker 4 Well, in 2005, a trade agreement called the Multi-Fiber Arrangement expired. The provisions within that agreement had been sort of like being phased out by design over the course of like a decade.

Speaker 4 But in 2005, it went away. And what that meant was that the United States had fewer import caps on textile products that were being brought in from developing nations or less wealthy nations.

Speaker 4 And that sort of, I mean, it ended the garment industry in the U.S.

Speaker 4 as we know it, basically, because what became possible was all these manufacturers and retailers to look for manufacturing overseas in far less wealthy countries, countries that would allow them to, you know, release more pollution into the environment, that would sort of kowtow to their interests in various ways that, you know, the United States is not a perfect country by any means, but there are basic protections on worker safety in the environment that make it more more expensive to manufacture here.

Speaker 4 So suddenly brands could move their manufacturing overseas. Retailers could source inventory from factories overseas that were charging far less.

Speaker 4 All of these financial incentives just changed apparel as we know it.

Speaker 3 This sounds like a monumental change, and yet the word multi-fiber arrangement is not something that anyone would stop and notice, even though from what you're saying, it's completely upended our closets and our lives.

Speaker 4 Why? This agreement was written to expire. And then when it expired, a lot changed about clothing in the United States.

Speaker 4 What it did essentially was placate the domestic garment industry with 30 years of protection, but then guarantee that when that 30 years was up, you know, it would sort of be open season.

Speaker 4 So it got the garment industry to sort of sign off on their own eventual death.

Speaker 3 So 2005 is a critical year. What does the post-2005 period look like?

Speaker 4 2005 was a watershed moment, but it wasn't as stark as it might have been if the protection provisions of the agreement hadn't been designed to be phased out. But in 2005, it's basically open season.

Speaker 4

That is the era where you get a lot of fast fashion retailers really expanding their presence in the United States. The first HMs start opening in the U.S.

You get Forever 21 sort of flourishing.

Speaker 4 So you have this sort of moment when

Speaker 4 there's this big rush into this new type of industry that can flourish in the United States. And that rush is built on sort of terrible clothing.

Speaker 3 Well, now you say terrible clothing. Do you mean terribly made clothing? Clothing with terrible fabrics? Because

Speaker 3 you could get a lot of trendy clothing cheaply.

Speaker 4 When fast fashion comes to the U.S., it brings with it its sort of internal financial logic.

Speaker 4 What that means is their goal is to sell as much clothing as possible, and they need to create the prices that allow them to do that.

Speaker 4 And being able to move manufacturing overseas means that they can vastly reduce their labor costs and also use much, much cheaper materials.

Speaker 3 So we started with sheep and wool. What do we switch to?

Speaker 4 In sweaters, what this means is you're getting a lot of what is essentially plastic. That will show up on fabric labels as polyester or polyamide or acrylic.

Speaker 4 That's what you'll usually find in sweater waves.

Speaker 4 You also get what is basically rayon, and you're starting to see a lot more in sweater knits of viscose, which is a fiber derived from bamboo, but it's derived in a way that is really, really deleterious to the environment in most circumstances.

Speaker 4 And

Speaker 4 that fabric can be manufactured in other countries with poorer environmental restrictions on industry. So you get a lot more of that material and a lot more plastic.

Speaker 3

You know, it's funny. It's not that I didn't notice fast fashion.

Of course, I have and have bought many a thing from its demonic jaws, but somehow the sweater existed in a different category.

Speaker 3 Like a sweater is such a significant thing.

Speaker 3 You know, if I think sweater, I still think a Billy Crystal fisherman fisherman thick sweater, even though I have not worn one or owned one in many, many years. That is what a sweater is.

Speaker 3 You just, we don't classify sweater as disposable.

Speaker 4 Right. And the basic designs of sweaters that you see have not changed much in the last, you know, 40 years.

Speaker 4 You still see cable knits, you still see turtlenecks, you still see the sort of fine-gauge knits more likely to be made from like an ultra-soft wool, like a cashmere or something like that.

Speaker 4 So because they've visually changed less over time, I think that people don't go into buying one expecting it to be disposable because it's still something that has like the look and feel of a thing that should be able to be worn for 10 years.

Speaker 4 Right, right.

Speaker 3 You know, what you're describing has been happening in a pretty rapid way for 20 years. Have we really not noticed that our sweaters were rapidly deteriorating for 20 years?

Speaker 4 Well, I think people have noticed it, but the consumer system is sort of like inherently individualistic.

Speaker 4 And people tend to approach problems that they encounter within the consumer system as something that they can sort of like MacGyver their way out of.

Speaker 4 Or if they're just like better educated, or if they look harder, or if they find like the secret source for like the good stuff, that this is a problem that they can solve.

Speaker 4 We don't think about consumption and about clothing and about changes in materials as like this sort of like collective issue, but that's really what it is.

Speaker 4 So I think that because we are not trained to look for for the sort of big hidden system behind why we have like the sweater options we have, it is hard for people to do that.

Speaker 4 And it's just hard to get. the type of view on the system that you would need in order to understand what's happening.

Speaker 4 Like if you are sort of like a sicko like me, you know, you do a lot of reading about this, you read academic stuff, you read books on the history of textiles, but this history is pretty well hidden.

Speaker 4 And the fashion industry goes to great lengths to purposefully hide this type of understanding of how its products are created and how that has changed over time.

Speaker 4 Because fashion marketing works best when you are just thinking about your own aesthetic and sensory experience of a garment.

Speaker 4 So there is like a real concerted effort on the part of the industry at large to encourage people not to put real thought into why suddenly the sweaters are like a little scratchier now.

Speaker 3 Yeah, yeah, that makes so much sense. I would also say that probably we let it happen because there's some ways that it's better because laundry is easier.

Speaker 3 I can have a sense that I'm accessing a luxury item for cheaper so that there are ways in which it's working for people.

Speaker 4

Absolutely. I think that the fashion industry does a great job of sort of like overall paying off consumers for not thinking about.

this stuff too hard.

Speaker 4 It is fun to have like a zillion options when you get dressed in the morning or when you are packing for a vacation or something like that.

Speaker 4 Having this type of variety and this type of choice is something that in the past was only available to wealthy people and to celebrities.

Speaker 4 And getting to sort of, you know, star in our everyday life with our own custom wardrobe is

Speaker 4

fun. Like, you know, putting on a cute outfit is fun.

Buying a new outfit is fun. Like, I love clothing.

I totally get why people.

Speaker 4 buy all of this stuff and why it's just a little bit easier not to like look too hard at the man behind the curtain.

Speaker 4 There is like not a lot of upside to people in looking into exactly where any of this stuff comes from, or like why it is ill-fitting, or why the seams split so easily, or why there's so much of it and there used to not be nearly as much.

Speaker 4 There's not really a lot of like personal upside to looking into that, except getting depressed.

Speaker 3 After the break, Amanda will teach us what to look for if we absolutely need a new sweater.

Speaker 4 Back in a moment.

Speaker 5 Running a business comes with a lot of what-ifs, but luckily, there's a simple answer to them: Shopify.

Speaker 5 It's the commerce platform behind millions of businesses, including Thrive Cosmetics and Momofuku, and it'll help you with everything you need.

Speaker 5 From website design and marketing to boosting sales and expanding operations, Shopify can get the job done and make your dream a reality. Turn those what-ifs into

Speaker 6 sign up for your $1 per month trial at shopify.com slash special offer.

Speaker 7 Anyone can follow.

Speaker 7 It takes something special to be an original, which is why the 2025 Lincoln Navigator SUV arrives with new ways of surrounding you in luxury, including the ultra-wide 48-inch panoramic display and the multi-sensory Lincoln Rejuvenate experience.

Speaker 7 A true original never stops evolving. So meet the 2025 Navigator, the original that's all new and better than ever.

Speaker 7 Learn more at Lincoln.com, Lincoln and Navigator at trademarks of Ford or its affiliates.

Speaker 3 Before we climb out of the hole, because we will climb out of the hole, besides split seams, what are the other collective costs? of this system

Speaker 3 for us, for people around the world?

Speaker 4 The things that the consumer system obscures are largely bad, especially when it comes to fast fashion. Garment workers overseas work in like generally terrible conditions.

Speaker 4

They work for very, very little money. A lot of them have very little control over their day-to-day lives.

Some of them live in dorms that are, you know, owned by their bosses.

Speaker 4 There's very little ability to sort of like live a happy, independent, secure life if you're a garment worker in most of the world.

Speaker 4 It is a really, really dark system underneath the surface in order to create all of this really, really inexpensive stuff.

Speaker 4 You know, if a sweater costs $10, that savings is coming from somewhere, and it's probably coming from the people in the system with the least power and the least ability to stand up for themselves.

Speaker 4 And then you also get a significant environmental impact from all of this. A lot of the countries that host these types of manufacturing outfits have fewer environmental protections.

Speaker 4 So, there is a ton of pollution that happens and a ton of human rights abuses that happen on the front end when things are being manufactured.

Speaker 4 And then, you just end up at the other end of that manufacturing process with a lot of physical waste.

Speaker 4 In order for fast fashion to work, companies have to manufacture far more than they can reasonably sell to people.

Speaker 4 So, you end up with a lot of excess clothing that gets dumped usually in poor countries.

Speaker 4 There are, in particular, particular, real problems with clothing waste being shipped to Ghana and Chile and then just dumped in these sort of like vast piles of waste.

Speaker 4

And the stuff we're talking about here is stuff that was never sold. It was never used.

It is pure front-to-back waste. That accounts for a lot of the textile waste in the world.

Speaker 4 But then also fabric recycling is really, really difficult. And a lot of things ultimately just cannot be recycled or it's not cost effective to recycle them.

Speaker 4 So because people's buying habits are sort of decoupled from any like actual need or want, people buy stuff that then doesn't get worn or that gets worn once, and then it ends up being donated.

Speaker 4 And a huge proportion of that ends up just being wasted. It cannot be recycled.

Speaker 4 So you've got more stuff for the great clothing waste piles in these poorer countries that are just essentially a dumping ground for us. So you've got plastics in waterways.

Speaker 4 You've got hazardous chemicals in waterways that are coming out of these garments that are just wasted. So there's a lot of waste and a lot of human suffering that comes out of this.

Speaker 3 I'm utterly paralyzed. I'm never going to buy anything again.

Speaker 3 I don't know exactly how spiritually to turn this shift because everything you said was sort of much more serious than the question I'm about to ask you. But the reality is it's cold.

Speaker 3 Sometimes I might maybe still want to buy a sweater for my niece, maybe, or I might have a friend who wants to one day buy a sweater not me i'll never buy anything again how do you magy for this

Speaker 4 there are still places out there where you can find a hundred percent wool sweaters made in factories in countries that have real protections for their garment workers that are made by companies that care about this type of stuff.

Speaker 4 It's a tall order to have to like do all that research yourself and try to sort through this.

Speaker 4 It is, in a lot of situations, maybe impossible, But sweaters, because they are so deeply tied to certain regions of the world and to long-standing garment traditions that are ongoing in those regions, if you look for sweaters that are made in Ireland, Scotland, New Zealand, a lot of those are going to be made with real wool from sheep that were treated pretty well and by people that are like skilled workers.

Speaker 4 And those don't have to be super expensive. A lot of those, you can have something like that for less than $200.

Speaker 4 And for a garment that you expect to

Speaker 4 last year after year after year and to serve like not just a fashion purpose, but a functional purpose in your wardrobe, part of this is just a mindset thing.

Speaker 4 If you let go of the idea that you need or want to sort of have a new wardrobe every season,

Speaker 4 I think it's easier to then go, okay, I am going to buy one $150 fully wool sweater and I am not going to get sucked in by the email sales and by Instagram ads and by all of these constant prompts that we receive to purchase additional stuff.

Speaker 4 Everybody that I talked to for this story said that their favorite place to get really good quality sweaters is through secondhand shopping.

Speaker 4 Because they're secondhand, you can get a good price on them. You can pay the same amount for one of these that you would pay for a brand new plastic sweater in a store.

Speaker 4 And then you're also not contributing to this larger issue of the constant cycle of new things that are being put into our physical world.

Speaker 3 I'm going to put a post-it note near my bed that says plastic sweater because I think if I'm ever tempted that phrase plastic sweater will dissuade me from buying anything new.

Speaker 3 I want to ask you about a couple of methods that now that I'm talking to you, I have used, but sound wrong.

Speaker 4 One thing is price, luxury.

Speaker 3 That does not necessarily, it sounds like, ensure that that my sweater is not plastic.

Speaker 4 Right.

Speaker 4 One of the most difficult things about like the consumer system as we experience it now is that price is pretty much entirely decoupled from any sort of expectation you should have about the quality of an item or the item's material composition.

Speaker 4 You say that so casually.

Speaker 3 That's that's so crazy. Like that is so confounding that it's that you said completely decoupled.

Speaker 4 Right. You know, sometimes a really, really expensive thing is is going to be really that much better than its less expensive counterparts, but usually not.

Speaker 4 Like, I don't think there's really any obvious correlation between the two anymore.

Speaker 4 It's pretty much certain that like if you're buying a $20 brand new sweater, what you're getting is terrible quality.

Speaker 4 But there's not any guarantee that if you've spent $3,000 on a sweater, that it's going to be like markedly better.

Speaker 4 Because the sort of logic of fast fashion has infiltrated a lot of parts of the fashion industry.

Speaker 4 People expect clothing will look old trend-wise, if not like wear-wise, as far as like quality goes, in six months. They expect to move on.

Speaker 4 So there's no real incentive for a lot of luxury brands to make their stuff to be like substantially better quality than some of the much cheaper options.

Speaker 3 So you can't rely on cost. Can you rely on

Speaker 3 tags? Like, can I just read the tag and see what it's made of? Or are there euphemisms there that I might not catch?

Speaker 4

The best thing that you can do is to learn what your fabric tags mean when you look on the inside of a garment. Wool means wool.

Cotton means cotton. Linen means linen.

Speaker 4 Polyamide, polyester, acrylic, those all mean plastic.

Speaker 4 Right.

Speaker 3 What about like Mongolian wool? Like I bought a sweater and it said 100% Mongolian wool. Is that just wool?

Speaker 3 Sometimes I'm afraid there's some euphemism that I never heard of and that's fake and there is no Mongolian sheep just in pictures. It doesn't really exist.

Speaker 4 Well, wool is sort of a catch-all term. It can come from a lot of different animals.

Speaker 4 So that level of detail is useful because it might tell you a little bit more about like the texture of the garment or how it will look over time with wear.

Speaker 4 Different wools do have different sort of physical properties.

Speaker 4 So that can be useful on that level.

Speaker 4 It doesn't necessarily tell you anything about quality, but wool is always like a good starting point to understanding what it is you're looking at and what it is you can expect from that garment and knowing what the sort of like less definitive words mean as well.

Speaker 4 Viscose, rayon, modal, these types of fabrics are generally the bamboo derived ones.

Speaker 4 And those while like technically a natural fiber, there's a lot that goes into the creation of that that is not necessarily very good for the environment or for the people working on it.

Speaker 4 So learning exactly what those terms mean too is useful. And you'll see the same ones over and over again.

Speaker 4 This is knowledge that, like, once you learn what all of this means, like, it is sort of knowledge that you can take with you for the rest of your life and be pretty set to go when trying to make like the very first most basic decisions about whether or not you want to buy something.

Speaker 4 If you can get yourself out of that headspace that says that you need more stuff, that you are missing things, it's a good idea for everybody to just slow down and go, okay, I've got five sweaters in my closet already.

Speaker 4 I have but one human body.

Speaker 4 I can only wear so many sweaters.

Speaker 4 Do I already have something that's similar to this and that I just haven't thought about in a while or that I just haven't tried on with the new pair of pants that I got that might look great with it?

Speaker 4 Like making yourself aware of what you already own and if it fits you and how it feels on you and how it might go with the things that you have already is good.

Speaker 4 Being familiar with your own wardrobe is good. And really just the problematic behavior here, no matter where you're getting your stuff, is just buying for the sake of buying.

Speaker 3 This episode of Radio Atlantic was produced by Kevin Townsend. It was edited by Claudina Bade, fact-checked by Yvonne Kim, and engineered by Rob Smersiak.

Speaker 3

Claudina Bade is the executive producer for Atlantic Audio, and Andrea Valdez is our managing editor. I'm Hannah Rosen.

Thank you for listening.