Can Baseball Keep Up With Us?

Interested in the changes baseball’s making? Read Mark’s article on how Moneyball broke baseball—and how the same people who broke it are back, trying to save it.

Learn more about your ad choices. Visit megaphone.fm/adchoices

Press play and read along

Transcript

Speaker 1

Your sausage mcmuffin with egg didn't change. Your receipt did.

The sausage mcmuffin with egg extra value meal includes a hash brown and a small coffee for just five dollars.

Speaker 1 Only at McDonald's for a limited time.

Speaker 3 Prices and participation may vary.

Speaker 4 Starting a business can seem like a daunting task, unless you have a partner like Shopify. They have the tools you need to start and grow your business.

Speaker 4 From designing a website to marketing to selling and beyond, Shopify can help with everything you need.

Speaker 4 There's a reason millions of companies like Mattel, Heinz, and Allbirds continue to trust and use them. With Shopify on your side, turn your big business idea into

Speaker 4 sign up for your $1 per month trial at shopify.com/slash special offer.

Speaker 3 Okay, my first question. Can you just list for me some rituals that baseball players do?

Speaker 2 Spitting into their hands and and rubbing their hands together, staring into space.

Speaker 6 Got him! Fernando Rodney shoots the arrow up into the Father's Day sky in Philly.

Speaker 2 Slapping their chest, flexes the shoulders, touches the helmet, readjusts the glove again, goes to the nose. Velcroing and un-velcroing their batting gloves, tipping their hat.

Speaker 2 Ozzy Smith ready for the flip and we're ready to start the season. Here we go.

Speaker 2 Balancing their hat, looking to the right field grandstand looking to the left field grandstand crossing themselves very unique routine when he steps into the batter's box tightens his glove up wristbands there's the feet a little two-step

Speaker 2 they invent new ones all the time it's completely dynamic a pitcher might tug at his cap and wiggle his leg when going into a motion do people lick their bass apparently yasail queek does

Speaker 2 yeah but no i i think that's a pretty rare thing. It sounds unsanitary, too.

Speaker 3 And what do these rituals have to do with baseball?

Speaker 2

Nothing, except that they have been there forever, and players have always had rituals. This is a big part of the problem in baseball.

This is why the people in charge have moved to make it faster.

Speaker 3 That is my friend Mark Liebovich, a staff writer at The Atlantic who gets all the best assignments. I'm Hannah Rosen, and this is Radio Atlantic.

Speaker 2 See, if you had known me 30, 25 years ago, you would have totally seen me be into a baseball game, but baseball just left me.

Speaker 3

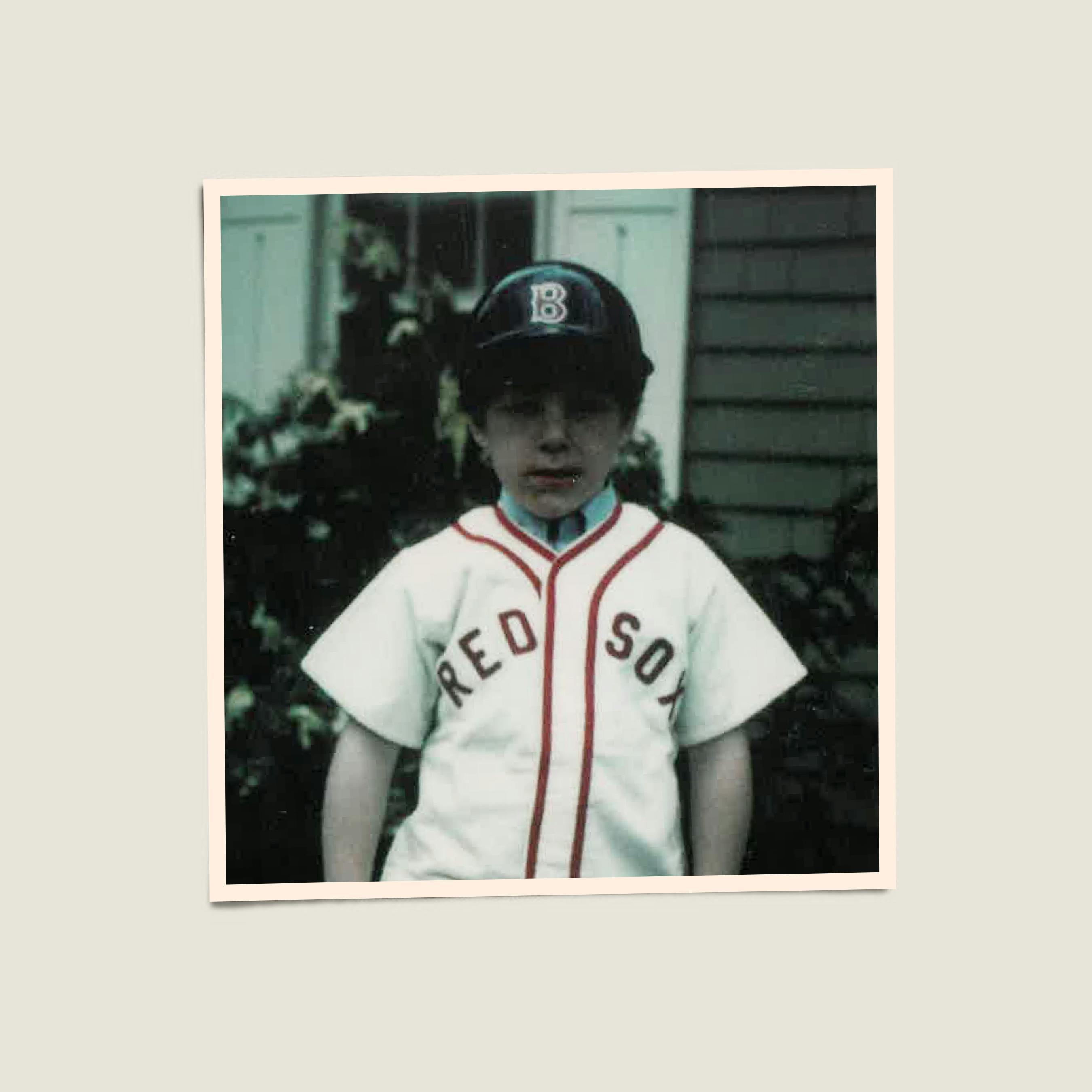

I've known Mark for enough years to see all the fan gear. Faded Red Sox hat.

Red Sox t-shirts with holes in them. Red Sox, socks.

Speaker 3 I've even seen a picture of little Mark at the game with his dad.

Speaker 2 Oh my god, the first spring training game. Like, my friends and I would, like, rush home from school to like listen to the first spring training gum on the radio.

Speaker 3 His love of this game, it was deep.

Speaker 2 Every year, my birthday party was all my friends coming, and we would play a game of pickup baseball at the intersection near the little cul-de-sac I grew up on.

Speaker 2 But it's not necessarily like little seven-year-old Mark here. I mean, if you had seen me, I guess I would have been in my late 30s.

Speaker 2 They had these like scintillating couple of playoff series where the Red Sox finally came back. I mean, those were some intense sports-watching things.

Speaker 2 I mean, this was like the culture of my youth, and that is just gone.

Speaker 3 Aaron Powell, Jr.: And is it gone because life is just so fast now?

Speaker 2

I think that's part of it. I think baseball has gotten much slower.

I mean, games literally took know, two and a half hours when I was a kid.

Speaker 2 Now, you know, as of last year, they took three hours, 10 minutes or so. So

Speaker 3 it's the two things moving in the opposite direction. It's like just as we were speeding up and getting faster,

Speaker 3 baseball just got slower.

Speaker 2 Yes, you have these two things moving in opposite directions. Baseball getting slower and our brains getting faster and our attention spans.

Speaker 2 shrinking and all of this was moving in a direction antithetical to enjoying baseball.

Speaker 3 It's funny when you put it that starkly, it actually makes me a little sad. Like we just have no room for anything

Speaker 3 slow in our busy lives anymore. Yes.

Speaker 2 And it's funny because we have these conversations and it's like, oh, baseball is to blame. It's these self-indulgent ritual doers who are velcroing and unvelcroing their batting gloves all day.

Speaker 2 You know, maybe this is just our problem. I mean, there are a lot of slow, reflective things we don't do anymore.

Speaker 3 So, Mark, when you set out to write about baseball, you thought the sport was dying, and then it did something to save itself, maybe.

Speaker 3 What did baseball do?

Speaker 2 They have initiated a set of rules, one, and most importantly, to make the game go faster, and two, certain rules to make there be more action and offense, less waiting around in baseball, more fun to watch.

Speaker 3 Got it. So just like faster, Everything faster, everything more exciting.

Speaker 3 What's one thing they did?

Speaker 2 Well, the big thing is a pitch clock.

Speaker 7 And Alvarez races out to beat the pitch clock. Senga stepped off, and when you step off with nobody on base, the pitch clock does not reset.

Speaker 7 And Alvarez realized that and charged out as fast as he could.

Speaker 2 A pitch clock is a new tool that has appeared in every major league ballpark this year in which there's this big clock in the outfield and also behind home plate in which like a literal clock a literal clock it counts down from 15 seconds a pitcher now has 15 seconds to pitch the ball or 20 seconds if there's someone on base and the batter has to be in the box ready to hit by the eight second mark so there's only eight seconds left they the batter has to be ready and what else did they do one of the things they did was they made the bases bigger which you know people can understand it's a bigger base now what that does is it encourages stolen bases it makes running bases a safer thing because you have more safe haven to grab onto or slide into.

Speaker 2 They're reducing pickoff throws, which took forever, and things like that. So they're encouraging more offense.

Speaker 3 This isn't like technical baseball language, but it does feel like a real vibe shift.

Speaker 2

It very much is. And it's hard to explain, but when you're actually watching a game, there is urgency.

Urgency is not a word that anyone would ever associate with baseball in recent years.

Speaker 2 No, it's you sit and you watch and people are not screwing around. And you sort of internalize that as a viewer viewer or a listener and you sort of say, wait a minute, things are happening faster.

Speaker 2 I better pay closer attention. I better not check my phone as closely.

Speaker 2 And so the whole vibe is, yes, maybe less relaxing, but ultimately more satisfying because more is happening and it's happening faster.

Speaker 3 And why did they make all these changes?

Speaker 2 Well, part of it is because baseball was falling farther and farther behind things like football and basketball and other sports that are a lot more compelling.

Speaker 2 They go much faster and frankly are more national spectacles. Like everyone gathers to watch the Super Bowl.

Speaker 2 So I actually went to a World Series game last fall between the Phillies and the Astros, and I drove up to Philadelphia. And, you know, it was a World Series game, and it was a no-hitter.

Speaker 2

The Astros pitchers, four of them, combined to no-hit the Phillies. This was historic, or theoretically, it was historic.

No one really noticed. No one remembers it.

Speaker 2 And this is a World Series game, the likes of which are routinely being

Speaker 2 outrated on TV by early season NFL games.

Speaker 2 I mean, as our culture speeds up, as brains speed up, you know, by, you know, cell phones and computers and just the attention spans and just the whole culture is sped up,

Speaker 2 baseball has slowed down. And finally, they just sort of decided to all at once just get very tough and say, okay, there is now a clock in baseball.

Speaker 2 Lo and behold, it has already shaved 25, maybe 30 minutes off a game in the first couple of months in this season.

Speaker 3 So who is the main architect of speeding baseball up?

Speaker 2 There are a few of them, but probably the best known is a guy named Theo Epstein, who is this legendary figure in baseball. He was the youngest general manager in history.

Speaker 2 He was named general manager of the Boston Red Sox at age 28.

Speaker 2 He is known for bringing the first World Series championship to Boston for 86 years.

Speaker 2 He then left the Red Sox, went to the Chicago Cubs, who had an even longer World Series drought, and he delivered after 108 years.

Speaker 2 So he sort of has this legend attached to him, and he left the Cubs a couple of years ago, and he joined Major League Baseball as a consultant.

Speaker 3 Isn't Theo Epstein associated with the whole Moneyball revolution in baseball?

Speaker 2 Yes, he did not pioneer it. Billy Bean of the Oakland A's is given credit for that.

Speaker 2 But Theo Epstein is known as really the chief disciple who applied some of these new theories in baseball and actually won World Series with it for the Boston Red Sox and the Chicago Cubs.

Speaker 3

All right. Tell me if this is right.

This is what I understand about Moneyball. I read the book.

I saw the movie. So

Speaker 3 Moneyball was a revolution that, as I recall, was supposed to modernize baseball.

Speaker 3 Like instead of tracking one set of statistics about players, they tracked a different set of statistics about players, which turned out to be the actually critical factors in winning a game and allowed

Speaker 3 teams with fewer resources to beat like rich fancy teams. But also what I understood about Moneyball was that it was supposed to have fixed baseball.

Speaker 3 So didn't we fix baseball?

Speaker 2 You know, very interesting terminology here, and we're going to try to make it not complicated.

Speaker 2 It fixed baseball for teams trying to win baseball games, i.e. the Oakland A's, right, who have less resources and did more with less.

Speaker 2 The innovations we're seeing now, it's not about winning baseball games because the commissioner of baseball and now Theo Epstein, his consultant, they work for all of baseball.

Speaker 2

They work for the fans. They work for the interests of entertainment.

So it has nothing to do with a competitive advantage between the Oakland A's and the New York Yankees.

Speaker 2 It has everything to do with the entertainment attention span of someone watching a Disney movie or playing a video game or watching the Super Bowl or something like that.

Speaker 3 Moneyball fixed one set of problems, but then created another set of problems?

Speaker 2

Well, they created... a blueprint for teams to do better with less resources.

But it was a terrible thing to watch. I mean, it created more walks, more strikeouts, slower action.

Speaker 2 So, yeah, I mean, it solved one problem. It created any number of problems if you are a consumer of entertainment.

Speaker 3 You know, I get why they need to move faster. One of the things that you wrote about from the slow era, which I really appreciate, was this mental skills coaching.

Speaker 3 Like, I was surprised and maybe happily surprised to learn that they teach baseball players how to meditate in real time while they're on the field.

Speaker 2 Aaron Powell, in a sense, yes. I mean, that's been part of the 21st century revolution in baseball.

Speaker 2 And in the service of giving baseball players and teams a slightly better competitive advantage, they have taught mental skills, imaging, meditations, visualizations, things that you do.

Speaker 2 I mean, because sports, especially baseball, is a big mind game, right? You need to put yourself in a very relaxed state or a state that puts you in a good position to succeed.

Speaker 3

I mean, that seems so nice and enlightened. And like, that's what we tell our children to do when they're stressed out.

That's what we tell everyone.

Speaker 3 Like, we're all supposed to slow down and meditate.

Speaker 2 Yeah, it might be nice, but it also gets introduced into the culture, which by and large introduces more time and dawdling into the culture of baseball.

Speaker 2 So David Ortiz, Nomar Garciapara, Robinson Kano, they have these rituals where they take their deep breaths and they clap and they sort of see the field.

Speaker 2 And then the owner of the Seattle Seattle Mariners told me this.

Speaker 2 You know, he was teaching his son's Little League team, and all of a sudden, half the Little League team is trying to imitate Robinson Kano by stepping out during the at-bat and doing his little ritual.

Speaker 2 And so this is taking how, you know, we got to wait for Jimmy over here to do his little Robinson Kano-like ritual.

Speaker 2 And then John Stanton, the owner of the Mariners, said to me, look, we have just taught an entire generation of kids that it's okay to pace around the mound for however long and waste all this time.

Speaker 2 And I guarantee you, it would be a lot more interesting to watch Johnny try to dunk like LeBron James or like kick a soccer ball like Messi or something than it is Johnny from Seattle trying to imitate Robinson Kano between the two and one and two and two pitch.

Speaker 2 And so, again, in a very crude way, the pitch clock just sort of disrupts all of that all at once.

Speaker 3 You know what we haven't talked about?

Speaker 3 How the players feel about all of this.

Speaker 3 You talked to San Diego Padre star Juan Soto about the pitch clock. Let's listen to that.

Speaker 2 Do you think the clock is a good thing? Like, did the times of the baseball games used to bother you, or did you,

Speaker 2 did you ever get impatient sort of waiting for pitches to come and stuff, watching a game when you're playing in it?

Speaker 2 I feel like baseball, I mean, baseball, if you enjoy the games, you gotta give them time to think

Speaker 2 and to see, look around, look at everything.

Speaker 2 For me, we don't, I mean, I know for fans, sometimes

Speaker 2

it gets boring, but for baseball players, it will never get that. So you were never bored on a baseball game.

No, no, no, never.

Speaker 2 It's never too long. It's never too short.

Speaker 2 I'm just enjoying the game.

Speaker 3 What was your impression of what he was saying there?

Speaker 2

He was saying, like, look, this is my life. This is my job.

This is what I love to do. I don't care if you're bored.

I mean, I've had like...

Speaker 2 Many, many people I interviewed for this story say that a million different ways. Like, look, I can't worry about whether you're entertained or not.

Speaker 2 You know, I'm going to get fired if I lose this many games or if my batting average dips below, you know, two, whatever.

Speaker 2

No one was saying, oh, look, the ratings from last night's game were higher than the night before. Oh, ticket sales are up around baseball.

We are being more entertaining. No one cares about that.

Speaker 2 Nor should they.

Speaker 3 So the players feel one way, and we, the fans, feel another.

Speaker 3 So I guess that's why Padre Manny Machado, in his very first pitch clock game, was like, no, thank you.

Speaker 6

That's a strikeout. There's a violation.

Ron Culpa just wrung up Manny Machado.

Speaker 6 Ron Culpa, the crew chief, behind the plate.

Speaker 6 And somebody's been ejected. Looks like Machado.

Speaker 3 After the break, can Mark learn to love baseball again?

Speaker 8 CRM was supposed to improve customer relationships. Instead, it's shorthand for customer rage machine.

Speaker 8 Your CRM can't explain why a customer's package took five detours, reboot your inner piece, and scream into a pillow.

Speaker 2 It's okay.

Speaker 8 On the ServiceNow AI platform, CRM stands for something better. AI agents don't just track issues, they resolve them, transforming the entire customer experience.

Speaker 2 So breathe in and breathe out.

Speaker 2 Bad CRM was then. This is ServiceNow.

Speaker 3 There's only one place where history, culture, and adventure meet on the national mall,

Speaker 3 Where museum days turn to electric lights.

Speaker 3 Where riverside sunrises glow and monuments shine in moonlight.

Speaker 3 Where there's something new for everyone to discover.

Speaker 3 There's only one DC.

Speaker 3 Visit Washington.org to plan your trip.

Speaker 3 You've been to a pitch clock game.

Speaker 2

The first pitch clock game. Ooh.

Well, the first spring training pitch clock game.

Speaker 3 You were like in a box sitting

Speaker 3 with all these guys, right?

Speaker 2

It wasn't a box. It was actually a couple of rows up from the field in a spring training game with basically the orchestrators of this from Major League Baseball.

One of them was Theo Epstein.

Speaker 2 Another guy was Morgan Sword, who is basically the director of baseball on-field operations for Major League Baseball, who has been putting this all in place.

Speaker 3 And what were you guys talking about?

Speaker 2 Well, mostly we were watching the game. I mean, this is like the first day of school for Morgan and Theo.

Speaker 2 This is this thing they had been envisioning and trying to put in place for months and even years. And this was the first game in which it was actually happening.

Speaker 3 And were they nervous, like on edge? Like, what was the vibe?

Speaker 2

Morgan was extremely nervous. He was a basket case, and usually he's pretty chill.

So, yeah, that was pretty glaring.

Speaker 3 Why was he a basket case?

Speaker 2 He was a basket case because he has been thinking about everything that could possibly go wrong. First of all, he's being scrutinized.

Speaker 2 Everyone in baseball is watching to see how this first pitch clock game is going to go off.

Speaker 2 But he's also spent so much time talking to umpires, talking to players, talking to managers, talking to game officials, talking to clock operators.

Speaker 2 It's basically starting up a whole cabinet department within baseball that didn't exist before. And so obviously on day one, you're going to be nervous.

Speaker 2 So what's your um what's your

Speaker 2 yeah that's my experience as a fan been during this uh interrectum for you

Speaker 2 what about your son yeah i mean my son my 15 year old he was not

Speaker 2 i i can't help but notice his

Speaker 2 lack of desire to sit through a few and a half hour game really and

Speaker 2 so who is that uh that was theo epstein he was telling me about what his personal experience is as a baseball fan during this time when he's not affiliated with the team And he's saying his son is bored, like, can't watch baseball anymore.

Speaker 2 Yeah. Especially during the pandemic, I noticed so much of his life existed through

Speaker 2 gaming, Fortnite,

Speaker 2 10-15 and again.

Speaker 2 Obviously, it's a bit of a cliche that

Speaker 2 Gen Z generation that grew up on their phones

Speaker 2 lacked the patience.

Speaker 2

It's not a cliche, it's brain chemistry. It's real, yeah.

It's

Speaker 2 very real.

Speaker 3 So it's not just about our attention span. I guess what he is panicking about is that he's got these two sons who should be baseball fans, but they can barely pay attention for more than 10 seconds.

Speaker 2 Yeah, so this is a multi-tiered problem, right? So not only are older

Speaker 2 former fans' brains adapting to a faster life and moving away from baseball, there's also this new generation that doesn't even see what the fuss is about to begin with and aren't exactly reading Moneyball and reading George Will columns and watching Field of Dreams to sort of see what the fuss is about.

Speaker 3

It's It's actually pretty cool that you were present at the creation of new baseball. Yes.

The new era of baseball.

Speaker 2

I'm glad you appreciate this. Yes, because this was a momentous day.

And of course, you know, it was also a very mundane day. But yeah, it felt momentous.

Right.

Speaker 3 The first ever game in the new era of baseball. Yeah.

Speaker 3 Like, was it more fun? Did you like it? Did time move faster?

Speaker 2

So the game was very crisp. It was three to two.

I think Seattle won. Basically, you know, all these executives, they were rooting not for the Mariners or the Padres.

Speaker 2

They were rooting for this game to be very, very fast because they knew everyone would look at this as like, oh, this is the new baseball. We want it to work.

And, yeah, it was very enjoyable.

Speaker 2 I was very glad that the game took less than two hours and 30 minutes. I know Theo Epstein was, and he wanted to go take a nap.

Speaker 2 The person to my right wanted to catch a flight back to New York or wherever he was going.

Speaker 3 So people were like living their lives, I got to catch a flight, I got to do this, I got to do that, and it fit into their busy lives.

Speaker 2 Much more so.

Speaker 3

I can't really tell if you, Mark Liebovich, were into the game. Personally, I prefer just fast games.

You know, I like watching basketball. I like watching soccer.

Yeah.

Speaker 3 I want to maybe get on board with faster baseball.

Speaker 2 Yes.

Speaker 3 And so I guess I'm wondering where you are. Like, are you on board with faster baseball? Like, when you were there, were you like, oh, this is going to work?

Speaker 2

Yeah. I saw a minor league game a few years ago that had a clock clock, and I was like, yeah, this is it.

This is totally it.

Speaker 2 I mean, I was watching an NBA playoff game with my wife and my daughter, Nell, who said, you know, there's something really nice about a game that you know is going to last two hours and 20 minutes, which is, you know, there's a clock on the NBA game.

Speaker 2 And if you're a soccer fan, it's going to take two hours.

Speaker 2 The commissioner of baseball himself, Rob Manfred, said to me, Look, what in your life do you really want to do for more than two and a half hours at a shot?

Speaker 2 Even people sitting up in the front office or the commissioner of baseball would be like, wow, do we really have to watch this for more than two and a a half hours? Yeah. Yeah.

Speaker 3 Like the people who are supposed to be

Speaker 2 management, managers, commissioners, things like that.

Speaker 3

It's weird. I mean, I guess I just have to accept that this is where we are now.

Like we're just not people who have patience for a three-hour pastime. We don't.

We just don't have it.

Speaker 2

Right. And, you know, but here's the thing.

I mean,

Speaker 2

games literally did not take three hours in 1969. They took, you know, much less, like two and and a half hours or probably less than that.

I don't know.

Speaker 2 Maybe people then would have had less patience then. But again, these two things are moving in opposite directions.

Speaker 3 Aaron Powell, let's say we shaved enough time off baseball that it lasted the same amount of time as it did when you were a kid. Right.

Speaker 3 Do you think you could ever feel about baseball the same way you felt about baseball when you were a kid?

Speaker 3 Do you actually feel like you could feel the same way?

Speaker 2 I mean, look, can you feel the same way about something as a 50-something-year-old as you did when you were seven or eight?

Speaker 2 I mean, you have sort of a much less mature brain when you're a kid, for better or for worse.

Speaker 2 You know, you see the world much more clearly, much more innocently, much more, you know, with much less sense of proportion and so forth. So I don't know.

Speaker 2 And maybe my fandom growing up is shaped by nostalgia now that I think about it and talk about it. I would think so, because right now I associate it with good times for my youth.

Speaker 3

Trevor Burrus, Jr.: So it feels like where we are this summer is that we, the fans, really want baseball to change. The players are somewhat resistant.

The rules are in place.

Speaker 3 Do you think that this will save baseball?

Speaker 2 I think it will help baseball. I think early results are that it has helped baseball.

Speaker 2 If you go by the actual shrinking time of games, if you go by the ratings and the ticket sales and so forth, the first few months of the season has been very encouraging.

Speaker 2 The larger point is, you know, is this sort of putting a band-aid on a larger sort of existential problem that baseball is ultimately not going to be able to deal with?

Speaker 3 All right, so now that you're done with your reporting and there are no legends inviting you to sit in their boxes with them and talk to Juan Soto,

Speaker 3 are you going to go to any games?

Speaker 2

Yeah. I mean, again, a lot of it comes down to.

Was that like, yeah.

Speaker 3 No, you know, or was that like, yes.

Speaker 2 I will, yes. And I'll tell you what what probably

Speaker 2

the decider will be. I mean, I'm parochial.

I care about my team, the Red Sox. Red Sox were not supposed to be good this year.

Speaker 2 They're kind of mediocre, but they're an entertaining team, and I have cared about them, so I have watched. If they

Speaker 2 completely implode, I'll probably stop watching. So like Juan Soto and him wanting good numbers, I want my team to do well, and I will probably drop off.

Speaker 2 You know, if I do go to a game this year, I'm thrilled that it's not going to go past 11 11 o'clock. Right.

Speaker 3 So it's, it's love, but it's conditional love.

Speaker 2 Totally.

Speaker 3 Like they've won you back, but conditionally.

Speaker 2 100%.

Speaker 3 I think where I'm at is I still would rather see a Washington Spirit game.

Speaker 3 But if somebody,

Speaker 3 say a child of any, any child, anybody's child, asks me to go to a game, I won't recoil in horror.

Speaker 2

Like, I'll be like, yeah, okay, sure, I'll try it. Here's what I'll say to you, and it's very intimate, but I'm going to invite you to a game.

We both live in Washington, so we're going to go.

Speaker 2

And whoever wants to join us can join us. And hopefully the recoiling in horror will not transpire.

And if it does, we can just leave.

Speaker 3

This episode of Radio Atlantic was produced by AC Valdez. It was edited by Claudina Bade.

Our engineer is Rob Smirciak. Our fact-checker is Michelle Soraka.

Speaker 3 Thank you also to managing editor Andrea Valdez and executive editor Adrienne LaFrance.

Speaker 3 Our podcast team includes Jocelyn Frank, Becca Rashid, Ethan Brooks, Kevin Townsend, Theo Balcombe, and Van Newkirk. I'm Hannah Rosen and we'll be back with a new episode every Thursday.

Speaker 3 If you like it, tell some Red Sox fans or some Yankees fans.

Speaker 2 Whatever.

Speaker 3 Tell all the fans.