Our Strange New Era of Space Travel

“Space is a vacation now… a status symbol,” Marina Koren explains to Adam Harris. The two staff writers discuss this new age of commercial space flight and the changes it’s bringing to how we see our place in the universe.

Today’s spaceflight has taken a wider variety of people, billionaires or not,beyond Earth’s gravity. As people with diverse perspectives take the journey, will that complicate how we as a species think about space?

Koren also spoke with William Shatner about his trip at age 90 and he reflects on why his experience ran counter to that of his most famed character: Star Trek’s intrepid optimist, Captain Kirk.

Learn more about your ad choices. Visit megaphone.fm/adchoices

Press play and read along

Transcript

Speaker 1 What makes a great pair of glasses? At Warby Parker, it's all the invisible extras without the extra cost.

Speaker 1 Their designer quality frames start at $95, including prescription lenses, plus scratch-resistant, smudge-resistant, and anti-reflective coatings, and UV protection, and free adjustments for life.

Speaker 1 To find your next pair of glasses, sunglasses, or contact lenses, or to find the Warby Parker store nearest you, head over to WarbyParker.com. That's warbyparker.com.

Speaker 1 Running a business comes with a lot of what-ifs. That's why you need Shopify.

Speaker 1 They'll help you create a convenient, unified command center for whatever your business throws at you, whether you sell online, in-store, or both.

Speaker 1 You can sell the way you want, attract the customers you need, and keep them coming back. Turn those what-ifs into why-nots with Shopify.

Speaker 1 Sign up for your $1 per month trial at shopify.com/slash special offer. That's shopify.com/slash special offer.

Speaker 1 Would you want to go to space?

Speaker 3 Um, yes, because it's really cool and interesting. I want to be a scientist when I grow up.

Speaker 4 Would you want to go to space?

Speaker 5 Yeah, buy one fly rocket ship.

Speaker 5 What's in space?

Speaker 5 Planets and stars and a rocket ship.

Speaker 1 I love that so much.

Speaker 1 That was really cute. What is in space? That's a great question.

Speaker 4 It is a great question.

Speaker 4 This is Radio Atlantic. I'm Adam Harris.

Speaker 1 And I'm Marina Coren.

Speaker 4 This week on the show, we're talking about space. We just heard some of our colleagues' kids talking about space.

Speaker 4 And as a parent myself, it feels like, you know, the images of space are inescapable, right? One of the first t-shirts I remember buying my daughter was a NASA t-shirt, right?

Speaker 4 We have blankets in our house that have, you know, moons on them and rocket ships. Was that sort of your recollection of childhood?

Speaker 1

Definitely. I had those glow-in-the-dark stars on my ceiling and, you know, occasionally one would fall off and spook me.

But I recently got a set for my three-year-old nephew.

Speaker 1 I mean, this is a go-to source of wonder and excitement for kids, for sure.

Speaker 4 And I should say that we are both staff writers, but you're the one on the space beat.

Speaker 1 Yeah, I am the Atlantic's Outer Space Bureau Chief.

Speaker 4 And it's been a big year to be a space reporter, right?

Speaker 1

It has. Yeah, we are definitely in this strange new era of exploration.

It's been 50 years since the last time human beings have set foot on the moon. 1972, that was the Apollo 17 mission.

Speaker 1 It was the final moon landing. I think the universe is a lot more familiar to us now because we've come such a long way.

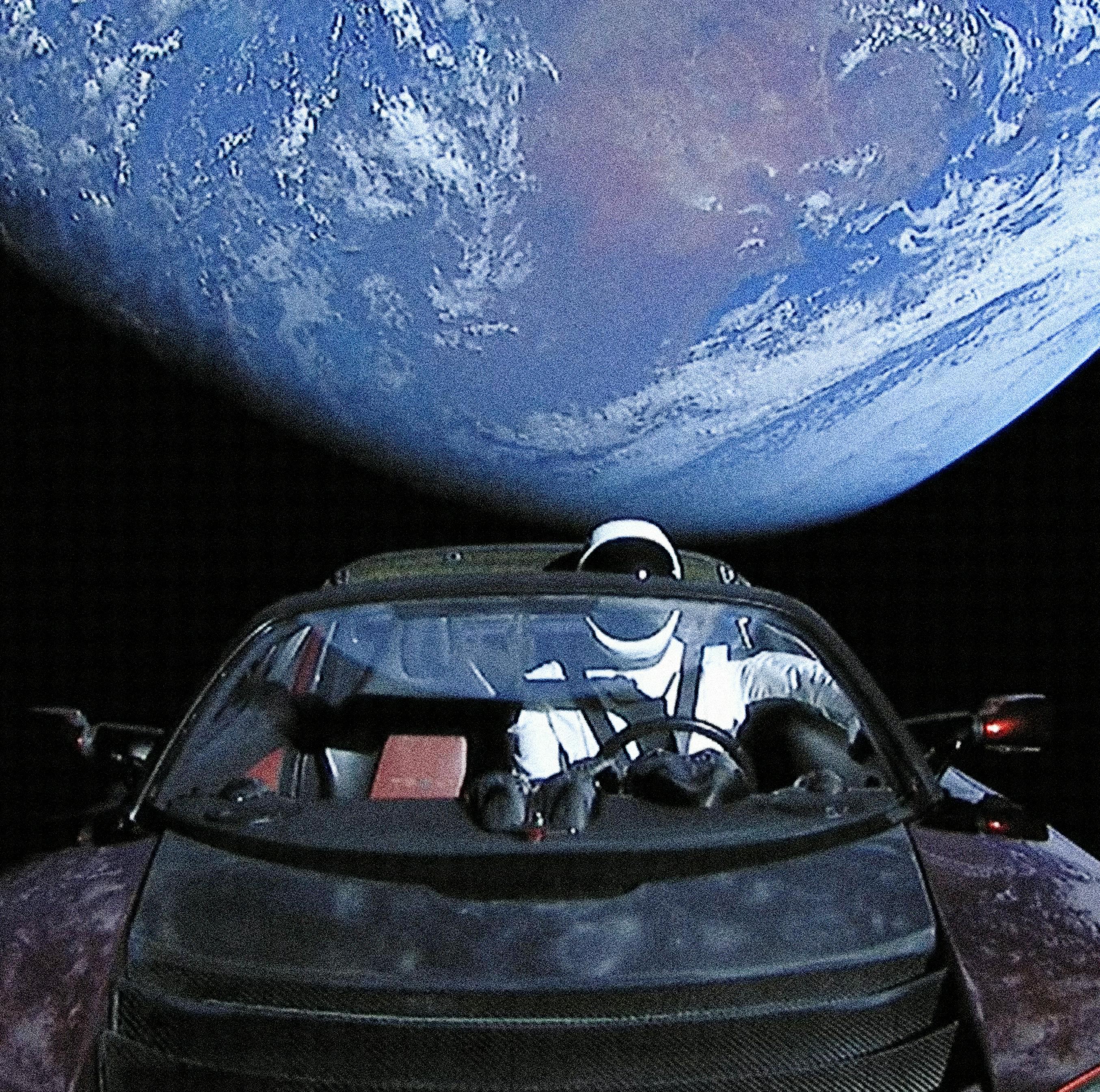

Speaker 1 But something that's really, really different now is that you have commercial companies that are doing the work that was traditionally done by governments.

Speaker 1 There's SpaceX, Elon Musk's company, and Blue Origin, Jeff Bezos' venture.

Speaker 1 And even 10 years ago, if you told someone, yeah, I think SpaceX is going to be launching people to the International Space Station, they might have laughed at you. It seemed ridiculous.

Speaker 1 But this is the reality now. I mean, it feels like we're in this strange sci-fi future where space travel is something you can buy.

Speaker 1 It's a type of vacation, you know, and it becomes a status symbol in a way. Now people can go to space and come back and tell everyone, well, I've been to space.

Speaker 1 I've done something that only about 600 or so people have done in the history of humankind.

Speaker 4 Before you sort of have the private space travel, you think of folks like John Glenn or you think of folks like Buzz Aldrin, someone with military training who has studied to be an astronaut like their entire life, right?

Speaker 4 What does it mean that that that's no longer the only type of person that's going into space?

Speaker 1 I think that spaceflight is about to get really, really interesting because the stories that we've heard from spacefarers, they've come from a specific group of people.

Speaker 1 Like you said, you know, these were more often than not, white men with military backgrounds, trained in a certain workplace culture that values the right stuff and values being stoic and unafraid in the face of something dangerous.

Speaker 1 But in this new era of commercial spaceflight, you're going to be seeing a wide range of participants.

Speaker 1 There will hopefully be more women, more people of color, people from underrepresented groups, from different educational and socioeconomic backgrounds, and people with just a wide range of experiences.

Speaker 4 What are the stories that we've heard about the experiences in space, right? These professional astronauts, when they come back, What do they say space was like?

Speaker 1 Yeah, there are a few common themes. So people, when these astronauts have gone to space and they've seen Earth from that perspective, they have been overcome with emotion at the beauty of Earth.

Speaker 1

And it suddenly becomes very clear just how thin our atmosphere is. And that is the only thing that really protects our planet from everything else.

So, they're struck by the fragility of the planet.

Speaker 1 And then, something else also happens to a lot of astronauts when they go to space.

Speaker 1 They suddenly feel a sense of connectedness with their fellow human beings down below because from space, you can't see any borders. There are no national borders, right?

Speaker 1 It's just continents and seas and clouds. And so many astronauts have come home and described these feelings.

Speaker 1 And the stories are indicative of a cognitive shift almost that is known as the overview effect.

Speaker 1

You know, I've talked to astronauts who say that they were taken aback by the borderless world. world and how beautiful that is.

And that made them feel like, you know, why are we at war?

Speaker 1 Why is there conflict? Why are all these things when you have like, we're a one planet? And it made them feel whole.

Speaker 1 I've also talked to one academic who did an extensive study of astronauts, and she couldn't reveal this astronaut's name to me, but she said that this person, when he went into space, he took one look out the window and was convinced that humanity was going to destroy itself in, you know, some hundred number of years, right?

Speaker 1 And so that experience could be profound and inspiring to one person, but it could also actually make another feel despair.

Speaker 1 And what's happening now with space tourism and private spaceflight is that the people going into space now, they've heard these stories of the overview effect. It's a thing.

Speaker 1 And so they're expecting to feel a certain way when they go to space. They're expecting to have a profound change on their perspective of the world and even maybe on their personalities.

Speaker 1 And so I wonder if we're kind of overhyping that. And I have talked to a few astronauts, professional NASA astronauts, who agree.

Speaker 1

They worry that these spaceflight companies and their sales pitches to customers are overselling the effects of the overview effect. It's not a guarantee.

It's not a gift from the universe.

Speaker 1 It's something that a person experiences and feels individually. And your mileage will vary.

Speaker 4

Yeah. And you said these flights are like a couple of minutes.

Is that enough time to change you?

Speaker 1

That is a great question. So I talked to Frank White, who is the person that coined the term term the overview effect.

He came up with it when he was flying on a plane.

Speaker 1 So not in space, but he had a pretty good view. And he got to thinking future generations of humans who might be living and working in space would have this distant view of Earth all the time.

Speaker 1 And they would have these insights that regular Earthbound people lack.

Speaker 1 And he was surprised that people who were flying on Blue Origin and having a few minutes of weightlessness were coming home and talking as if they had had this profound experience.

Speaker 1 They were saying it changed them.

Speaker 1 And he was surprised because he thought that in order to really get the full hit of the overview effect, you had to spend some time in space, you know, weeks to months in orbit around Earth or even all the way out on the moon.

Speaker 1 That's kind of the literature that we're working with here.

Speaker 1 And I think that's what's going to change in this era of commercial spaceflight because you are going to have people who are not like the Apollo astronauts.

Speaker 1 And they're going to be coming home with different stories and really widening the overview effect that we've become familiar with as a public.

Speaker 1 And the future participants won't be restricted by some of the constraints that the professional astronauts were.

Speaker 1 So, if you were a professional astronaut and you went to space and you didn't have a great time,

Speaker 1 I don't think you could say that once you came back from space and you came home to Earth because that could potentially affect your future flight assignments.

Speaker 1 You know, you had to have a certain response on your way home. And so, I think we're about to hear some of the most honest stories of spaceflight that we've ever heard before.

Speaker 4 Yeah, I was actually going to ask, you know, is the overview effect real, right? If we only have this limited pool of stories to pull from, is that theory a sort of real thing?

Speaker 4 Have all of the folks who have gone up to space sort of shared that view?

Speaker 1 That's a great question. And I think the way we talk about the overview effect, it becomes like this mystical, magical thing,

Speaker 1 right? Like astronauts are revered people.

Speaker 1 Even when I have in the past interviewed astronauts, when they walk into the room in their full flight suits with all their mission patches on the fabric, and you can't help but feel intimidated because you think, wow, this person has seen something that I've never seen.

Speaker 1 And so we think of the overview effect and the experience that people should have in space as something that the universe gives us, but it's actually a cultural phenomenon, right?

Speaker 1 It has been shaped by a certain group of people working under a certain set of pressures who wanted to make sure that they could fly again so they couldn't say anything outrageous.

Speaker 1 And the overview effect also came out of a certain time and place, right? Many of these stories come from the midst of the space race in the middle of the Cold War.

Speaker 1 That definitely shapes a person's perspective.

Speaker 1 So I would say that seeing Earth from space is not a one-size-fits-all reaction.

Speaker 4 What are some of the interviews that stuck out because they may have differed from this idea of an overview effect?

Speaker 1 So I spoke with the William Shatner about his space flight, which he was, he was 90 years old when he took that trip.

Speaker 1 I recorded some of my conversation with Shatner, and he said it was a really transformational experience, but not for the reasons that we're used to hearing.

Speaker 1 We're going to take a quick break and we'll be right back.

Speaker 6 Charlie Sheen is an icon of decadence. I lit the fuse and my life turns into everything it wasn't supposed to be.

Speaker 1 He's going the distance. He was the highest paid TV star of all time.

Speaker 6 When it started to change, it was quick. He kept saying, no, no, no, I'm in the hospital now, but next week I'll be ready for the show.

Speaker 2 No.

Speaker 6

Charlie's sober. He's going to tell you the truth.

How do I present this with any class? I think we're past that, Charlie. We're past that, yeah.

Speaker 1 Somebody call action.

Speaker 6

AKA Charlie Sheen, only on Netflix, September 10th. Tires matter.

They're the only part of your vehicle that touches the road. Tread confidently with new tires from Tire Rack.

Speaker 6 Whether you're looking for expert recommendations or know exactly what you want, Tire Rack makes it easy.

Speaker 6 Fast, free shipping, free road hazard protection, convenient installation options, and the best selection of BF Goodrich tires.

Speaker 6 Go to tire rack.com to see their BF Goodrich test results, tire ratings, and reviews, and be sure to check out all the special offers. TireRack.com, the way tire buying should be.

Speaker 7 Space, the final frontier.

Speaker 4 So you got to talk to Captain Kirk.

Speaker 1 I did, yes.

Speaker 7 These are the voyages of the starship Enterprise.

Speaker 7 Its five-year mission. to explore strange new worlds, to seek out new life and new civilizations,

Speaker 7 to boldly go where no man has gone before.

Speaker 1 I will admit, I have never seen Star Trek before.

Speaker 4 So we have a Space Beat reporter who's never seen Star Trek.

Speaker 1 But you've seen it.

Speaker 4

I have seen Star Trek. It was playing pretty frequently on our TVs when I was a kid.

My dad rarely missed episodes or reruns.

Speaker 4 So, for people like Marina who don't know who Captain Kirk is, he was the captain of the Starship Enterprise on Star Trek in the 1960s, the original captain.

Speaker 7 Do you wish that the first Apollo mission hadn't reached the moon, or that we hadn't gone on to Mars and then to the nearest star?

Speaker 4 And he was this really optimistic figure, this really sort of classical hero.

Speaker 2 Risk.

Speaker 7 Risk is our business.

Speaker 7 That's what the starship is all about.

Speaker 4 What did Shatner have to say about going to space? Like actually being there?

Speaker 1

Yeah, when I talked to him, it was about a year after his experience. And the flight was still really, really fresh in his mind.

I mean, I asked him, how was it? How are you feeling a year out?

Speaker 1 And he just dove right into a Shatner-esque monologue about going to space.

Speaker 2 We had emerged from the film of air that surrounds the Earth, and we're weightless. I got out of my five-point harness and made my way to the window.

Speaker 2

And I saw a wake of air, like a submarine might be in the water, leaving a wake. And then I looked to my right, which was facing space.

And when I looked up there, I saw nothing but blank.

Speaker 2

palpable space. The blackness was so overwhelming.

My immediate thought was, My God, that's death.

Speaker 2 And then I looked back and I could see with great clarity the beginning of the circumference line of the earth, the color of the desert that I had just left, which was beige, the whiteness of the clouds, and the blueness of the air.

Speaker 2 Those three

Speaker 2 colors, in deference to the blackness, I was overwhelmed by the sense of death and overwhelmed by the sense of nurturing by the earth.

Speaker 1

When Shatner came back from his quick trip to space, he's standing outside the capsule. There's other people around him.

Jeff Bezos is there.

Speaker 1 Bezos is popping champagne like a frat boy and like flinging that in the air. And Shatner is just standing there super still.

Speaker 2

First of all, I didn't know what I was feeling, but I was weeping. And I didn't know why.

And everybody else is celebrating.

Speaker 2 It took me a couple of hours sitting by myself to understand that what I was feeling was grief and the grief for the earth.

Speaker 1

He is overcome with emotion. He is weeping.

And I'm watching that and I'm thinking, oh no, what's going on? Is this man okay?

Speaker 1 And then he starts saying how he was just taken aback by the blackness of space, the ugliness of space, how it looked like death.

Speaker 1 And I don't know if I'm making this up, but I swear I could see Jeff Bezos' face like twitching. Like, that's not going to be good for the marketing materials, right?

Speaker 1 So Shatner was super, super honest about his experience. And when I talked to him, he said that that grief was still with him.

Speaker 1 You know, Earth was beautiful and gleaming and delicate from that perspective, but it just reminded him of everything that's wrong on the ground and particularly made him think about how unstoppable climate change feels.

Speaker 1 And so for him, this was in many ways a negative experience. And Shatner was starting to cry when we were talking about it because the experience is so fresh in his mind.

Speaker 1 And, you know, nothing about climate change and the prognosis there has really changed in the last year since he went to space. So that grief was still with him.

Speaker 4 How was his experience different than what he may have imagined that he would feel after going up to space?

Speaker 1

Yeah, he told me that he expected... to see Earth and just be reminded of how beautiful and wonderful this planet is.

And I think he expected it to be reaffirming in a positive way.

Speaker 1 And it's interesting to think of this man who played a character who was this really big space optimist in real life going to space.

Speaker 1 And his initial emotional reaction to that is grief and sadness and all kinds of negative emotion.

Speaker 1 I think what Shatner shares with other astronauts is, you know, when people have gone to space, they have felt an overwhelming desire to take care of the planet, right?

Speaker 1

You really see that this is all there is. This is all we know, at least.

And if this is our one home on this floating ball of rock in the void, then we should take care of it.

Speaker 1 And so, you know, there's a case to be made that the more people go up into space, that feeling will trickle down and lead to some type of meaningful improvement on Earth.

Speaker 4 You know, if somebody gives you a ticket on a $20 million flight, you're not going to be able to say,

Speaker 4 well, that wasn't, you know, exactly what I expected it to be.

Speaker 1 But Shatner.

Speaker 4

was able to do something different. Why was his experience different than, say, others who have been up to space and came back down and just said, oh, it was great.

Thanks. Thanks, Jeff Bezos, for

Speaker 4 putting me on this flight.

Speaker 1

Right. Thanks, Mr.

Bezos.

Speaker 1

I mean, William Shatner is William Shatner, right? He was 90 years old during his space flight. He's Captain Kirk.

I think he doesn't owe Jeff Bezos anything.

Speaker 1 Yes, Bezos comped his ticket and that's lovely, but someone like William Shatner going into space,

Speaker 1 they can come back and say what they want because the public looks at them in a different way.

Speaker 1 You know, if a very wealthy person decides to comp the tickets for an electrician, for a nurse, you know, and they go up and come down,

Speaker 1 can they speak their minds very freely? I don't know.

Speaker 4 Say a billionaire called you up and was like, hey, Marina, love your stories. You want to go to space? Would you go if you got the opportunity?

Speaker 1

Oh, man. Well, there would be some conversation about journalistic ethics and all that to get through.

But would I ever go to space? I'm going to say no. Really?

Speaker 1 Because

Speaker 1 space flight is risky. You never know what might happen, what could happen.

Speaker 1 I don't want to die on the job not having filed my story.

Speaker 1 Like if something happens, if I'm somehow incapacitated, I come back and I can't write the story, that will haunt me.

Speaker 1 I still, planes freak me out. I still can't believe that we can get planes off the ground and land them back in one piece.

Speaker 1 And, you know, space is not at that level yet, but maybe maybe someday it will be. And that's pretty wild to think about.

Speaker 4 Yeah, actually, to that point, right? Thousands of people fly at high altitudes every day.

Speaker 4 Do you think that there's a future where spaceflight is going to feel as sort of commonplace as taking a flight to LaGuardia?

Speaker 1 I think that future is possible. I think what we have to be careful about is making too many promises.

Speaker 1 Like if you listen to Elon Musk or Jeff Bezos talk about spaceflight right now, you know, they're suggesting that this future is right on, like, this is happening next week.

Speaker 1 And I don't think that future will happen that quickly. It's true that more people than before are going to have the opportunity to go to space now.

Speaker 1 I'm not sure if in my lifetime there are going to be spaceships full of people going into the moon. There might be.

Speaker 1 I mean, SpaceX and Elon Musk are working really, really hard to make that future a reality.

Speaker 1 You know, SpaceX's next generation moon rocket could reach orbit on a test flight, but could reach orbit as early as next year.

Speaker 1

SpaceX has already sold tickets to people to go on a trip around the moon. Like these things are happening.

How quickly they actually become reality, I don't know.

Speaker 1 Maybe 50 years from now, when we're 100 years out from the Apollo program anniversary, maybe it will feel a bit more mundane, just like a plane ride.

Speaker 4 And is some of the mystique fading from space or space travel? Are we sort of becoming desensitized to space travel?

Speaker 4 Because I mean, those first couple of commercial flights, it was, you know, 24-hour news cycle. Like it was, you know, they broadcast all of them, but that sort of slowed down.

Speaker 4 Are we sort of becoming desensitized to the awe and wonder of space travel?

Speaker 1

I think that's possible. I think of the Earthrise picture that showed the whole complete Earth that was taken by the Apollo 8 crew in 1968.

And I think that picture was mind-blowing to people, right?

Speaker 1 They'd never seen Earth like this before.

Speaker 1 50 years later, I think our brains are so spoiled, maybe even rotted by special effects that I do wonder if the sight of Earth from space is going to be that shocking, especially when you have, you know, so many people going into orbit and coming back and posting on Instagram, like, here's what it looked like.

Speaker 1

Yeah, like we've seen what Earth looks like. We've seen some incredible CGI.

I do wonder if our modern brains might be less impressed impressed by the view than maybe people were in the 1960s.

Speaker 1 But I also don't know if that's just some dumb millennial take.

Speaker 4 It's like if somebody goes up and they're like, this isn't what interstellar looked like.

Speaker 1 Where's the wormhole?

Speaker 4 Where's the wormhole? I was expecting wormholes and all I see is, you know, as Shatner said, right, this great blackness of space.

Speaker 1 This episode of Radio Atlantic was produced by me, Kevin Townsend, along with Theo Balcombe and Claudina Bade. It was engineered by Erica Wong and fact-checked by Anna Alvarado.

Speaker 1 Thank you to Adam Harris and Marina Corin for hosting and a special thanks to the kids of the following Atlantic staff. Jocelyn Miller, Honor Jones, Anna Bross, and Claudina Bade.

Speaker 1 Thanks for listening and have a wonderful new year.

Speaker 1 What do you think space is?

Speaker 2 Um

Speaker 3 Space is space.

Speaker 1 I love space is space. That sounds like me on a day with Writer's Block trying to write the first sentence of my story.

Speaker 1 What do you think space is?

Speaker 5 Well, I think space is a deep black void of nothingness.

Speaker 5

And when you get far into it, there are no stars and planets. It's just blackness, and there's no escaping.

Also, I think at the end of space, there is heaven.

Speaker 1

Wow. Minnie William Shatner, Minnie Shatner.

I love it.