For Love of the Game

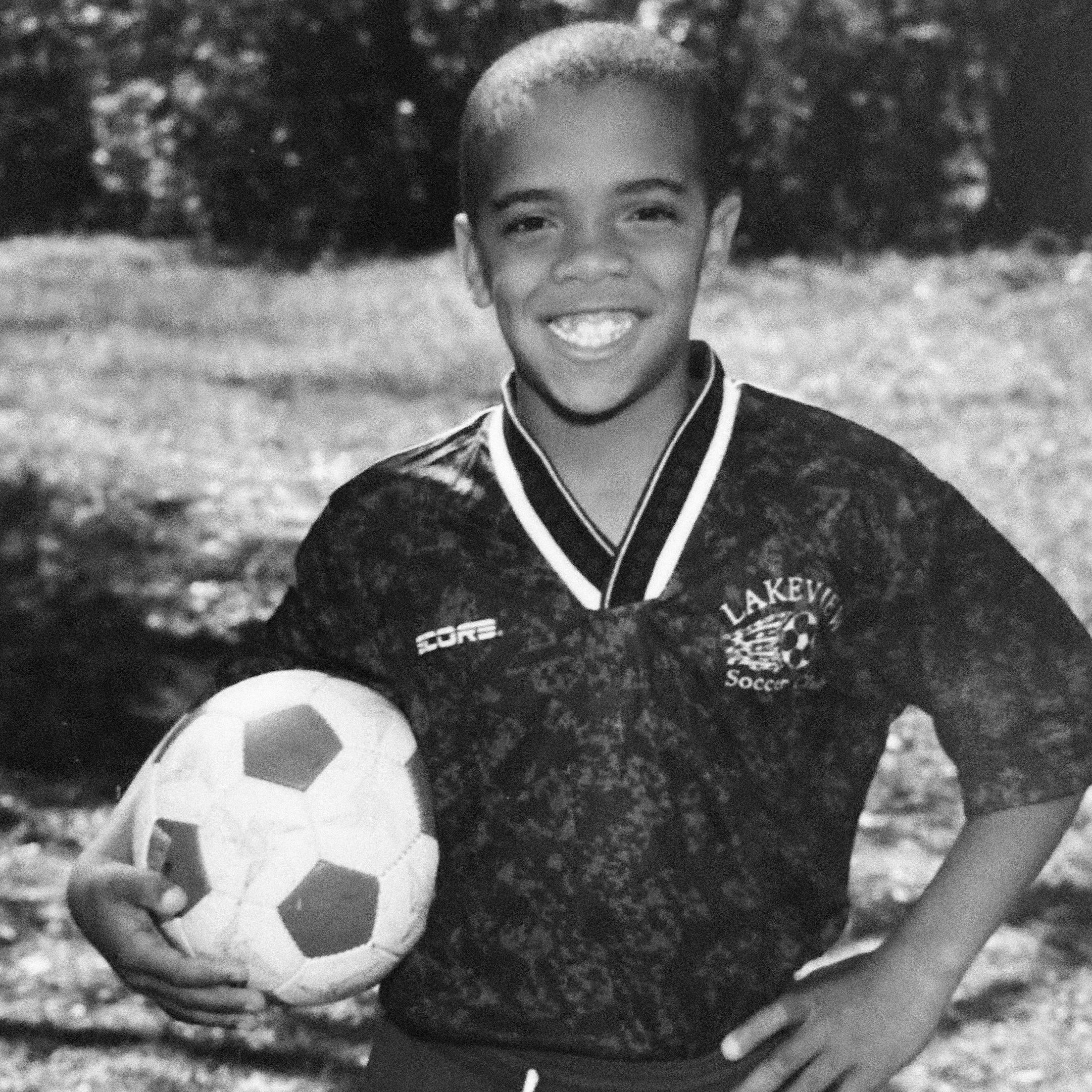

Smith’s attachment to the game is personal, stretching back to when he first started soccer playing as a little boy. In this episode of Radio Atlantic, Smith talks about the joy of soccer, the overt racism in the game, and why he’ll be cheering for the team of a small country in West Africa.

Tape in this episode comes from FIFA, UEFA, ESPN, and TRT.

Learn more about your ad choices. Visit megaphone.fm/adchoices

Press play and read along

Transcript

Speaker 1 Hattiday presents in the red corner the undisputed undefeated weed whacker guy

Speaker 1 champion of hurling grass and pollen everywhere and in the blue corner the challenger extra strength patted

Speaker 1 eye drops that work all day to prevent the release of histamines that cause itchy allergy eyes

Speaker 1 and the winner by knockout is patted

Speaker 1 pattiday bring it on

Speaker 3 There's a reason Chevy trucks are known for the dependability because they show up no matter the weather, push forward no matter the terrain, and deliver.

Speaker 3 That's why Chevrolet has earned more dependability awards for trucks than any other brand in 2025, according to JD Power.

Speaker 3 Because in every Chevy truck, like every Chevy driver, dependability comes standard. Visit Chevy.com to learn more.

Speaker 3

Chevrolet received the highest total number of awards among all the trucks in the JD Power 2025 U.S. Vehicle Dependability Study.

Awards based on 2022 models and newer models may be shown.

Speaker 3 Visit jdpower.com/slash awards for more details. Chevrolet, together, let's drive.

Speaker 2 Hey there, I'm Clint Smith, staff writer at the Atlantic. And joining me for a couple special episodes this year about the World Cup is my fellow staff writer and fellow Arsenal fan, Franklin Forer.

Speaker 2

What's up, Frank? Come on, you gunners. Come on.

So, Frank, there's a little bit of the age difference between us.

Speaker 2 Not much. Not much.

Speaker 2 It's all in your head.

Speaker 2 What is age? It's an imaginary construct. But if we are to lean into that imaginary construct, for me, in the 90s, I was a kid who was just beginning to fall in love with the game.

Speaker 2 I started playing for the first time in 1994 when I was six years old. And I'm curious what your relationship to the game was.

Speaker 2 Like when I was discovering my love for the game and making my way through grilled cheese sandwiches and rec league soccer. You were thinking about the game in much more sophisticated terms.

Speaker 2 Don't let the grays in my beard confuse you, Clint.

Speaker 2 I'm not your grandfather.

Speaker 2 But my defining World Cup experience, I think, was 1990, the Italia World Cup. I was going into 10th grade, and I fell in love with Cameroon.

Speaker 2 And they had a player, Roger Mila, who was the indomitable lion himself. He was an aging player.

Speaker 2

And he just kind of single-handedly took this team and carried it through the tournament. He's very underrated in the history of the game.

Doesn't get his due. Totally doesn't get his due.

Speaker 2

And nearly knocked out England in that tournament. That was the game that I was kind of hanging everything on.

And I just so desperately wanted Cameroon to knock out England. And that English team.

Speaker 2

had a lot of great players on it. There was something about him and the way that he played.

And to me, the game has always, I've always loved the political undercurrent of it all.

Speaker 2 I viewed this through the lens of anti-colonialism.

Speaker 2 And that was always the thing that kind of unlocked the game for me was that I could latch on to the fact that it was a morality tale, but I loved what I was seeing in the stands.

Speaker 2 And for me, the contrast between the passion of supporters there and the crowds that I would experience at an American sporting event just left me envying just the sheer authenticity of what I was seeing, not just on the pitch, but in the stands.

Speaker 2

So during the 1990 World Cup, I was two. So I don't have much of a memory of it, unfortunately.

But for me, in the 90s, the World Cup I remember the most is the 1998 World Cup.

Speaker 2

I think I was nine years old, nine going on 10. And I was sitting down and I had this grilled cheese sandwich.

The Louisiana heat and humidity, it was like 120 degrees outside or something.

Speaker 2

And so I was inside sort of getting respite. And we didn't really watch a lot of soccer in my house.

I was the first person in my family to ever play soccer.

Speaker 2 I still didn't watch it, but that changed in 98.

Speaker 2 I was watching South Africa play France, and it was, I caught the tail end of the game, and they had this sort of 20-year-old, super-fast, lightning-quick-winger named Thierry Henry.

Speaker 2 And makes the heart go Pitter Patter. Oh, Pitter Patter.

Speaker 2 And there's this incredible moment at the end of the game where, you know, it's like the 90th minute. We're in stoppage time.

Speaker 2 He collects the ball, he nutmegs the South African defender, pushes it past another one, runs around them, dinks it over the keeper, like feathers over the goalie.

Speaker 4 Tierry Uri

Speaker 4 picking up this ball and a little bit of brilliance here finally working it in. Ari, little trip and goal.

Speaker 2 Does sort of like a Roger Federer drop shot where the ball, you know, when it hits the ground, it has this backspin and it wrongs, puts another defender and then it goes in and the crowd goes crazy.

Speaker 2 And I'm sitting there with my grilled cheese and it's getting cold and my mouth agape. And I was just like, that was incredible, right? And this happened all in like five seconds.

Speaker 2 And the thing that I love too is that he looked like me. And this was a moment when, you know, especially in Louisiana, especially in the 90s, like there weren't a lot of black kids playing soccer.

Speaker 2 I think I was either always one of two, if not the only black kid on my team. For me to be able to look up and see

Speaker 2 a player who was so exciting and surrounded by teams like the South African team and the French team was like a really special and really affirming thing, even though I didn't necessarily have the language for it in that moment.

Speaker 2 It was so important for me to see him because it allowed me to see or project onto him a version of myself. And I needed that.

Speaker 2 So now we're in 2006, just graduated from high school, about to start college. And I have a far more developed understanding of the world.

Speaker 2 And one of the things that I'm beginning to more fully understand are the ways that the history of racism are baked into contemporary American life.

Speaker 2 And one of the ways I think I began to more fully understand that was because the year prior, Hurricane Katrina had swept across my hometown.

Speaker 2

80% of New Orleans was underwater. We were so far removed from any notion of a post-racial society.

And part of what shaped my increasing consciousness around

Speaker 2 what racism is and what it looked like and how it manifests itself wasn't just Katrina, but it was also the previous few years of watching some of the things that had happened in the global soccer community.

Speaker 2 I remember seeing Samuel Etto, who was this Cameroonian player who played for Barcelona, being taunted by fans, being called a monkey. There were black players who had banana peels thrown at them.

Speaker 2 There were black players who were physically assaulted, and it just felt like it kept happening.

Speaker 2 And sometimes what happened is that these players would try to walk with the feel and say, I'm not going to allow myself to be subjected to this.

Speaker 5 But the reality is, throughout Europe, soccer players of color are often subjected to racist acts and language as they play what is known as the beautiful game overseas.

Speaker 2 People coming from Osa are living in

Speaker 6 Germany, no, not just in Germany, but everywhere in the world.

Speaker 2 In France, they have the same problems.

Speaker 7 And the idea that this is a new Germany that they've merged over the last few years, a very inclusive one where it doesn't really matter what your last name is and what your skin color is, that's all seems to have blown up in our faces.

Speaker 2 They created this big hoopla and uefa the european soccer federation said that they were going to be more stringent in punishing racist acts both from players and from fans but it was becoming clear that even though for so many of us soccer is a sort of sanctuary

Speaker 2 there were limits to how much of a sanctuary it could be

Speaker 2 i was on my high school team i was a sophomore We played this high school Dutchtown

Speaker 2 and we ended up winning. It was just one of those moments where your feet feel light, your lungs feel full, and you just feel like anything is possible when you touch the ball.

Speaker 2

I dribbled past a few of their defenders and sent a cross into the box. And one of my teammates headed it in and really solidified the victory for us.

I was enthralled.

Speaker 2

We were moving to the next round. We would eventually win the state championship that year, our school's first ever boys' soccer state championship.

I was just excited.

Speaker 2 And then the game ended, and I walked over toward the stands where our parents were, where some of the other kids from our school were.

Speaker 2 And people's faces seemed

Speaker 2 incongruent. And why does everybody seem uneasy or stressed or anxious? And I would come to learn later when I dribbled past a bunch of defenders and crossed it into the box.

Speaker 2 That one of the folks in the stands on Dutchtown side, they said, take that nigger out.

Speaker 2 And,

Speaker 2

you know, my dad turned around. He tried to see who it was who said that.

There was like this

Speaker 2 situation in the stands. And

Speaker 2 I'm struck by how I didn't even notice when I was on the field, but

Speaker 2 I remember the sort of feeling in my body, even just being told that that had happened, the stress that felt like it stretched out its tentacles across my whole body.

Speaker 2 And so when I saw these black players in Europe being called monkey, being being having bananas thrown at them, being called all sort of racial slurs and epithets, I realized that no matter if you were playing on a high school field in Louisiana or if you were playing in a stadium in Barcelona, none of us were immune to that.

Speaker 2 And going into the World Cup in Germany, that was a big fear that a lot of people had, is that some of the big moments of sometimes violent assaults of racism would take place in Germany.

Speaker 2 And obviously, when so many people think of Germany, they think of the violence that the German state has enacted on the proverbial other with the World Cup coming up.

Speaker 2 And it felt like it was heightened with some of the things that were happening on the field. So in 2009, I was a junior in college and I decided to study abroad in Senegal.

Speaker 2 I had taken French my whole life and still wasn't as good as I thought I should be. I wanted to go to a French-speaking country,

Speaker 2 but I wanted to go to a place that I

Speaker 2 didn't know if I would go otherwise. It's almost cliche to talk about it this way, but like I went there and it changed my life.

Speaker 2 I mean, it was my first time ever on the African continent, and it was such an interesting moment, too, because Obama had just been elected in the United States.

Speaker 2 And when you show up in Dakar, I mean, his face was everywhere.

Speaker 2 His face was on buses, it was on cars, it was on bumper stickers, it was in inside of shops, it was in barbershops, it was in grocery stores, right?

Speaker 2 And I think there was a sort of diasporic proximity that they felt to him. It was an interesting experience because I'm the descendant of enslaved people, but clearly, I am someone of African descent.

Speaker 2 Living in Senegal was also this moment where I gained like a clear sense of how

Speaker 2 soccer was really this connector across nationalities, across cultures,

Speaker 2

across lines of difference. But I remember you show up in Senegal and you bring a soccer ball to the beach and you're immediately 20 people's best friend.

Everybody's barefoot.

Speaker 2 The waves are sliding up and down the shore. You're playing as much against each other as you are against the tide.

Speaker 2 It was just so

Speaker 2

free. And that was so different from my previous soccer experiences, which, you know, I played competitive soccer as a kid.

I always thought I was going going to be a professional soccer player.

Speaker 2 And it was the first time in a long time where I was able to play free of any expectation, free of any underlying sense of competition.

Speaker 2 I was just kind of learning to love the game again on its own terms.

Speaker 8

Your sausage McMuffin with egg didn't change. You receipt it.

The sausage McMuffin with egg extra value meal includes a hash brown and a small coffee for just $5.

Speaker 8 Only at McDonald's for a limited time.

Speaker 2 Prices and participation may vary.

Speaker 3 Charlie Sheen is an icon of decadence. I lit the fuse and my life turns into everything it wasn't supposed to be.

Speaker 2 He's going the distance.

Speaker 5 He was the highest paid TV star of all time.

Speaker 3

When it started to change, it was quick. He kept saying, no, no, no, I'm in the hospital now, but next week I'll be ready for the show.

Now, Charlie's sober. He's going to tell you the truth.

Speaker 3

How do I present this with any class? I think we're past that, Charlie. We're past that, yeah.

Somebody call action.

Speaker 3 Aka Charlie Sheen, only on Netflix, September 10th.

Speaker 2

So now it's 2010, a year after my time in Senegal. The memories of that time are in so many ways still very fresh.

And the World Cup is being held in South Africa.

Speaker 2 And what you should know is that an African team has never made it past the quarterfinals of the World Cup. Every four years, five African teams qualify for the World Cup.

Speaker 2 And as of 2010, only two African countries had had ever qualified for the quarterfinals. None had made it to the semifinals.

Speaker 2

But in the 2010 World Cup, which was held in South Africa, Ghana was playing Uruguay in the quarterfinals of the World Cup. And they had a real shot.

And it looked that way.

Speaker 2

You know, the game was tied. It was tied 1-1.

Then a minute left was in the game. And ultimately, Ghanaian captain Stephen Appia has this header.

Speaker 2 cleared off the goal line by Uruguayan forward Luis Juarez. But then another Ghanaian player heads the ball toward the goal, and it looks like it's going to go in.

Speaker 2

It looks like Ghana is going to be the first African team in the semifinals. It's this historic moment on the African continent.

African team makes it to the semifinals.

Speaker 2

Maybe they'll make it to the finals. Maybe they'll win.

All of these thoughts are going through everybody's head as they watch this ball about to go into the net.

Speaker 2 But then Luis Suarez, the same player on Uruguay, who had blocked the ball from going in before, he blocks it again, but this time it's with his hands.

Speaker 9

What a dramatic hit. There's a red card coming out as well.

Well, the answer is drama right at the end here.

Speaker 9 And the red card is shown.

Speaker 2 And so there's this wild moment where like all the Ghanaian players are going crazy. Everybody's like, you know, they can't believe what they just...

Speaker 2

It's like the number one thing you learn about soccer when you're a kid. It's like, don't use your hands.

And he very explicitly used his hands. So he gets a red card and he's sent off.

Speaker 2 And Ghana have a penalty kick. And so now everybody's like, all Ghana has to do is score this penalty kick.

Speaker 2 And they will be the first African team in history to make it to the semifinals of the World Cup. Everybody in the stadium in Johannesburg is cheering for Ghana, right?

Speaker 2 There's again this sort of diasporic proximity, this collective sense of African-ness.

Speaker 2 And for those of us who are black Americans, we're watching and we're like cheering for the proverbial motherland.

Speaker 2 And so, Asimojian, this Ghanaian forward, he scored two penalty kicks in the World Cup so far.

Speaker 9 Asamoa Gian has the opportunity to send Ghana into the semifinal.

Speaker 2 He steps up,

Speaker 2 kicks the ball,

Speaker 2 and he hits the bar.

Speaker 2 And then it hits the crossbar. Unbelievable.

Speaker 2 And it doesn't go.

Speaker 2

And all of the Ghanaian players drop to their knees. They can't believe it.

The whistle blows. Uruguay can't believe they're still in this.

Speaker 2 And then they go on to win the game just a few minutes later on penalty kicks. And Africa's best chance, maybe in history, of making the World Cup semifinals are just gone.

Speaker 2 This moment it still hurts so much because you just see how close they were. What would it have meant if Ghana had won the World Cup in Africa? But we'll never know.

Speaker 2

And now, you know, Luis Juarez is like this huge villain. Yeah, it sucked.

It really sucked.

Speaker 2

And so this year in the 2022 World Cup, there's Ghana, Morocco, Cameroon, Senegal, and Tunisia. Senegal is the reigning African champion.

They won the Africa Cup of Nations not too long ago.

Speaker 2 They have the reigning two-time African player of the year, Sadio Mane, who previously played for Liverpool, now plays for German Powerhouse Bayern Munich.

Speaker 2 And I think Senegal has a really good chance to make a very solid run in this tournament. I mean, they're the champions of Africa.

Speaker 2 They have one of the best players, not only in Africa, but like Sadio Mane is one of the best players in the world. And so who knows?

Speaker 2 This might be the moment where an African team makes it past the quarterfinals. Maybe it's the moment where more than one African team makes it past the quarterfinals.

Speaker 2 So I would love nothing more than to see Senegal make a strong run, than to see Ghana get what they deserve from that World Cup where they were robbed of a trip to the semifinals in so many ways.

Speaker 2 But it's going to be exciting either way.

Speaker 2 You know, it's interesting. My kids,

Speaker 2 until recently, I think

Speaker 2 very much felt like soccer was daddy's thing. But I took them to an arsenal game and we got the kids their chicken nuggets and french fries and pizza.

Speaker 2

And we were watching this new generation of players from all over the world. It felt so real to them.

It felt so three-dimensional to them.

Speaker 2 They understood the sort of human texture of the game in ways that they

Speaker 2 hadn't before, right? Before it was this thing that only existed on TV and now it was this thing that was real. You could feel the stadium vibrating under your feet.

Speaker 2 You could, you know, smell the person's french fries next to you. You could see the players on the field right in front of you celebrating.

Speaker 2 Now, my five-year-old, especially, he's like so into the game. I mean, it's almost striking how

Speaker 2

much this moment impacted him. And I told him, I was like, oh, yeah, and the World Cup is coming.

And he was like, the World Cup is coming?

Speaker 2 I mean, I didn't even know he really knew what the World Cup was, but I am

Speaker 2 very excited to be able to share that with my kids.

Speaker 2 And one thing that's really different about the 2022 World Cup as compared to the 1998 World Cup when I started watching over 20 years ago now is the fact that the United States men's national team has far more black players than they previously did.

Speaker 2 But now, I mean,

Speaker 2 there's so many black players on that team. I mean, I remember in one game during World Cup qualifying, I think there might have been eight black players out of 11 in the starting lineup.

Speaker 2 I mean, it was at a moment. I remember I texted Adam Serber and Adam Harris, two staff writers here at the Atlantic, and I was like, do y'all see this? Like, this is, I mean, it's, it's amazing.

Speaker 2 And they're all like in their early to mid-20s, you know?

Speaker 2 So it very much represents this new generation of black players who have come through the system and who represent, I think, a new set of possibilities for the game.

Speaker 2 You know, Tyler Adams, Weston McKinney, Tim Wea, Anthony Robinson.

Speaker 2 And that makes me really excited for nine or ten year old kids who might be watching the World Cup for the first time, like I did, you know, back in 1998,

Speaker 2 who are going to see so many different versions of themselves. And who might not, you know, in 2022, more black players are playing the game than ever before.

Speaker 2 And that represents something really exciting. And it represents like

Speaker 2 the country that we live in more accurately than

Speaker 2 previous teams.

Speaker 2 This episode was produced by Acey Valdez with help from Kevin Townsend. It was edited by Claudine Ebade and Sam Fentress is our fact checker.

Speaker 2 For more big picture takeaways about the 2022 World Cup from me and other Atlantic writers, check out our newsletter, thegreatgame at theatlantic.com slash newsletters.

Speaker 6 Popsicles, sprinklers, a cool breeze.

Speaker 2 Talk about refreshing.

Speaker 6 You know what else is refreshing this summer? I'll brand new phone with Verizon. Yep, get a new phone on any plan with Select Phone Trade-In and MyPlan.

Speaker 6

And lock down a low price for three years on any plan with MyPlan. This is a deal for everyone, whether you're a new or existing customer.

Swing by Verizon today for our best phone deals.

Speaker 6 Three-year price guarantee applies to then-current base monthly rate only. Additional terms and conditions apply for all offers.