#0018 - Terrence Howard

We break down Joe’s interview with Terence Howard, from May 2024.

Clips used under fair use from JRE show #2152

-

Snopes | Terrence Howard Holds Patent on Virtual Reality Technology?

-

Response to Terrence Howard’s AR/VR Patent Claims…from an XR Pioneer

-

Terrence Howard’s Gravity Theory: Rethinking Gravity and Its Public Impact

Intro Credit - AlexGrohl: https://www.patreon.com/alexgrohlmusic

Outro Credit - Soulful Jam Tracks: https://www.youtube.com/@soulfuljamtracks

Press play and read along

Transcript

Speaker 1 It's that time of year again, back to school season.

Speaker 1 And Instacart knows that the only thing harder than getting back into the swing of things is getting all the back-to-school supplies, snacks, and essentials you need.

Speaker 1 So here's your reminder to make your life a little easier this season.

Speaker 1 Shop favorites from Staples, Best Buy, and Costco all delivered through Instacart so that you can get some time back and do whatever it is that you need to get your life back on track.

Speaker 1 Instacart, we're here.

Speaker 2 Ready for a great night out? Top concerts are headed to Shoreline Amphitheater this September.

Speaker 2 Don't miss the chance to see your favorite artists like Neil Young, The Who, Thomas Rhett, Conan Gray, Above and Beyond, and many more.

Speaker 2

Nothing beats a great night of live music with your friends. Tickets are going fast, so don't wait.

Head to live nation.com to see the full list of shows and get your tickets today.

Speaker 2 That's live nation.com.

Speaker 3 On this episode, we cover the Joe Rogan Experience, episode number 2152, with guest Terence Howard. The No Rogan Experience starts now.

Speaker 3 Welcome back to the show. This is the show where two podcasters with no previous Rogan experience actually listen to and get to know Joe Rogan.

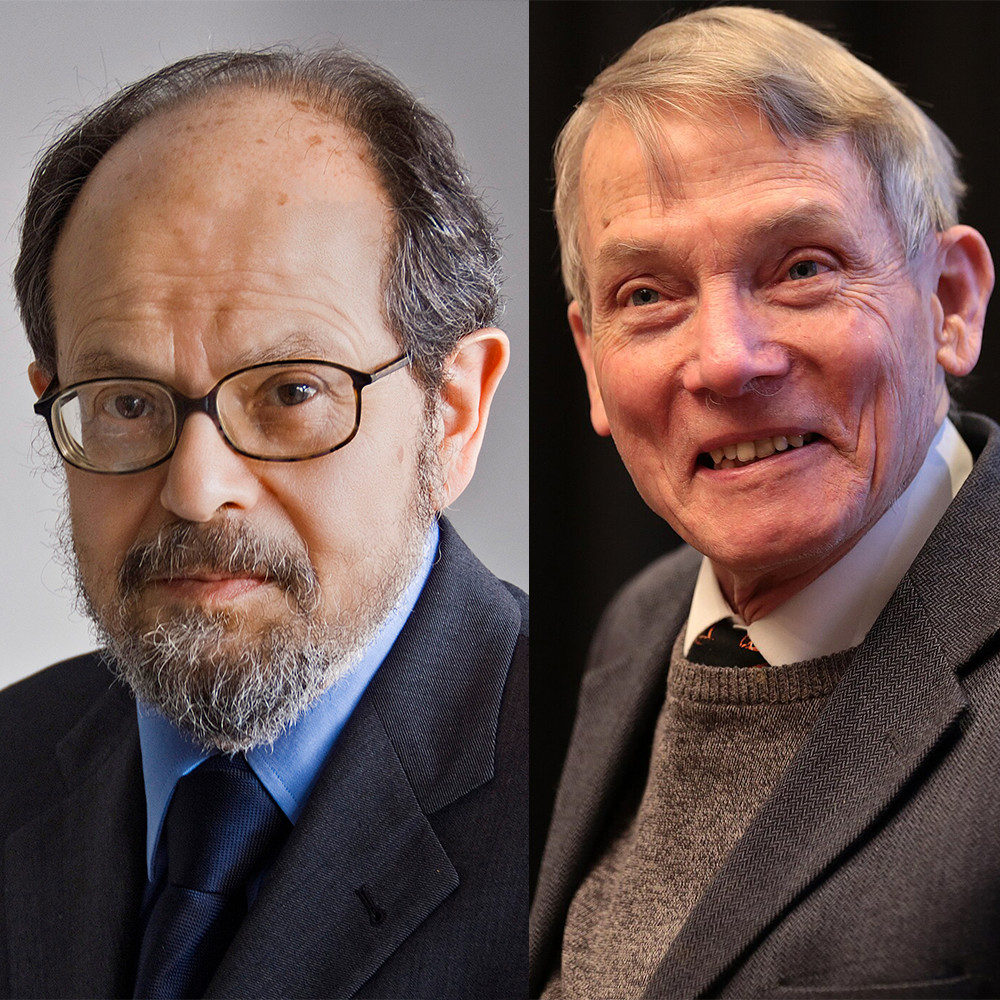

Speaker 3 It's a show for anyone who's curious about Joe Rogan, his guests and their claims, as well as just anyone who wants to understand Joe's ever-growing media influence. I'm Michael Marshall.

Speaker 3 I'm joined by Cecil Cicarello. Today, we're going to be covering Joe's May 2024 interview with Terrence Howard, an interview which has to date been viewed 11 million times on YouTube alone.

Speaker 5 Woof.

Speaker 3 So how, Cecil, did Joe introduce Terrence on the show?

Speaker 5 I'm just still reeling from 11 million views. Give me a second.

Speaker 3

Spotify numbers on top of that as well. We don't even know how many on Spotify.

I know.

Speaker 5

Insane. All right.

Here we go. So here's how he describes Terrence.

Speaker 5 Terrence Howard is an actor of stage and screen, lauded for his work in Crash, Iron Man, Empire, and Shirley, as well as a musician and researcher in the fields of logic and engineering.

Speaker 3 I got you. In Crash, was he the one that Don Cheadles played?

Speaker 5 Oh, no,

Speaker 3 he wasn't the one. He's not just being chased around

Speaker 3

by Don Cheadles. Sorry, that was unfair.

That was unfair. Is there anything else we should know about Terrence Howard?

Speaker 5 Yeah, so a couple things. First, Howard has had some very difficult marriages in his past, and that's something the media has written about.

Speaker 5 He pleaded guilty after punching his first wife in 2002, something he admitted in a Rolling Stone interview later.

Speaker 5 His second wife took out two separate restraining orders across a period of three years due to his physical abuse.

Speaker 5 His divorce agreement with his second wife was overturned in 2015 after a judge ruled Howard had signed it under duress

Speaker 5 because his former wife was threatening to sell nude pictures of him and other personal information.

Speaker 5 And I only bring this up because Terrence himself during this episode alludes to his previous marital woes and he significantly downplays his portion of it in a very big way to sort of, it makes it feel like he's sort of coming off as a victim.

Speaker 5 And I just wanted to make sure we mention that.

Speaker 3 Yeah, it's very much part of his kind of hero story that he tells to Joe as to how he came to all these amazing revelations and how much hardship he's overcome.

Speaker 3 So I think it is worth us knowing that the hardship he's overcoming includes this stuff where he admitted in court to domestic violence.

Speaker 5 Yeah, absolutely. There's also another piece too that we should mention.

Speaker 5 Howard's educational background. So Howard has stated that he went to school for chemical engineering and applied materials, though he didn't complete his engineering degree.

Speaker 5 Howard thinks of himself as an engineer and intends one day to complete the what he calls three credits worth of material that he's currently short.

Speaker 5

In February of 2013, Howard also said on Jimmy Kimmel Live that he earned a Ph.D. in chemical engineering from South Carolina State University.

Howard never attended that university,

Speaker 5 and it does not confer doctorates in chemical engineering.

Speaker 5 Instead, Howard was awarded an honorary degree of a doctorate of humane letters at DHL from that university when he spoke at the commencement in 2012.

Speaker 3

Gotcha. Okay.

So what did Howard and Joe talk about in this episode?

Speaker 5 You know, a lot of math, physics, engineering, how far back Terrence can remember, more math, several stops and starts about linchpins, how vortices placed perfectly create planets, how the sun poops out planets, and we would absolutely know a whole bunch more if Jamie could finally get that damn movie to play.

Speaker 3 There is a lot of issues with the tech going on here. Well, before we get to our main event, we do, as always, want to say a big thank you to our Area 51 all access past patrons.

Speaker 3 Those are Darlene with like four A's in a row in the middle of that sort. If you're a Darlene with three A's in a row, that wasn't for you.

Speaker 3

You have to actually subscribe yourself to get your shout out there. There's also definitely not an AI overlord.

Fred R. Gruthius.

Chonky Cat in Chicago Eats the Rich.

Speaker 3

Laura Williams, no, not that one, the other one. Stone Banana, Am I a Robot? Capture says no, but maintenance records say yes.

Martin Fidel and 11 Gruthius.

Speaker 3 They all subscribed at patreon.com forward slash no Rogan. You can do that as well.

Speaker 3 All patrons get early access to every single episode, as well as a special Patreon-only bonus show every single week.

Speaker 3 This week we're going to be talking about rebuilding Saturn, the sexuality of basic elements, and Terrence will keep trying to tell us about a new type of drone that he's invented, and he'll keep being distracted from doing so.

Speaker 3 You can get all of that, as well as all of our previous gloves-off segments from every other episode, for as little as a dollar an episode at patreon.com forward slash no Rogan.

Speaker 3 But for now, we're going to talk about Terrence Howard's revolutionary contribution to maths and physics in our main event.

Speaker 3 A huge thank you to this week's veteran voice of the podcast. That was Ash from Washington announcing our main event.

Speaker 3 I remember that you too can be on the show if you send us a recording of you giving us your best rendition of It's Time.

Speaker 3 You can send that to noroganpod at gmail.com and you can tell us how you're going to be credited when we mention you on the show.

Speaker 5 All right. So, much of this episode, the beginning portion of the episode, is going to be about Terrence Howard, who he is, and what he is revealing to the world.

Speaker 5 So, there's going to be some background information that we cover that Terrence covers, and then we'll be talking about that.

Speaker 5 And then we'll move into sort of the critique he's received, as well as the ideas that he's sort of

Speaker 5 expounding on most of the show with Joe Rogan. So, we're going to start out very early with with Terrence Howard talking about

Speaker 5 the first thing he remembers.

Speaker 4 How did you get started with all this?

Speaker 4 I didn't come into this world the way everybody else does, I don't think. I used to think that everybody had the similar experience, but like if I asked you, what was your first memory in life?

Speaker 5 What would it be? I don't think I know.

Speaker 4 My first memory was

Speaker 4 almost like when you're dreaming and you're falling and you hit the bottom and you wake up.

Speaker 4

That was my first memory, but I didn't wake up here. I was inside my mother's womb and I was about maybe six months inside the womb.

And I'm like, okay, don't forget, I'm here.

Speaker 5 Okay, okay.

Speaker 4

Don't forget, don't forget, don't forget, don't forget. You go to sleep, wake up again.

Now something's moving in front of you and you're like, oh, that's my friend. But I had a different name for it.

Speaker 4

I didn't know it was my hand, but I knew I had a title for it. Go back to sleep, all of those things.

Then ultimately you get ready to come out. I remember all of that.

You remember coming out.

Speaker 4 You remember being compressed, you know, and there's, you want to panic, but there's, you're flooded with like some serotonin and dopamine to where you feel relaxed. You go right back to sleep.

Speaker 3 So Terence thinks he can remember when he's born. Now, this isn't actually a terribly uncommon thing that some people will think.

Speaker 3 There's a percentage of people around the world who will think they can remember their birth. People can't actually remember their birth, though.

Speaker 3 What's normally happening is this will be an example of a constructed memory. So you know that your birth happened because you're here and everyone is born through a normal birth anyway.

Speaker 3 You've probably even been told stories about your birth, kind of the circumstances, whether it was a cesarean or a natural birth, all of that kind of stuff, you'll have been told at some point.

Speaker 3 And you will have osmosed, like just osmosed that information about your own birth and also about the information about what it's like to be in the womb, what a baby would experience, what the birth would be like.

Speaker 3 You kind of put all of that together from your family memories and your society and your culture. And then without realizing, you'll construct a memory of that as if it's your own.

Speaker 3

Because that's the weird thing about memory. It's incredibly weird and malleable.

It's not a snapshot. People like to think that you remember a thing and it's exactly as you remember it.

Speaker 3 And it's much more likely that you're remembering the last time you remembered something, which is only like remembering the time before you remembered something.

Speaker 3 And you kind of have this morphing of what was real. And because the memory works this way, people can actually be made to remember things that never happened to them.

Speaker 3 And this is interesting.

Speaker 3 There's lots of studies in this kind of area around false memories. Elizabeth Loftus is one of the, published one of the

Speaker 3 biggest kind of most respected studies in this area.

Speaker 3 She and her researchers managed to get people to remember a time that they got lost in a shopping mall, even though they never got lost in a shopping mall. They checked ahead of time.

Speaker 3 That never happened. But they would recount detailed memories of what it was like and how scared they were.

Speaker 3 Other people have recounted memories of going on a hot air balloon trip when they've never been on a hot air balloon trip and the picture that they're looking at was photoshopped to

Speaker 3

fake them into thinking that. So our memories are incredibly fallible and malleable.

And I suspect that's what's happening with Terrence here.

Speaker 3 But it does tell us literally 12 seconds into the episode, right out of the gate, maybe Terrence isn't the most reliable narrator about his own story and about how the universe works.

Speaker 5 Yeah, that's a great point. And I think that's why we're playing this, right? Like

Speaker 5 I'm not playing this to poke fun

Speaker 5 at Terrence.

Speaker 5 I'm playing this to show you that like within a few moments of the episode starting, we've already got somebody who's telling us something that is almost like, there is almost no way that this is true, right?

Speaker 5

There's almost no way that this is true, but it's something that they, that they genuinely believe. So we have to understand that that's how they're approaching the world.

And

Speaker 5 I just want to, can I be pedantic just for a second, really quickly? I just want to be, just, just for a second. Joe answers the question,

Speaker 5

what was your first memory with? I don't think I know. Yes.

And

Speaker 5 that is, then that's not your first memory, Joe.

Speaker 5

Your first memory is the first thing you remember. And I just want to, like when he said that, I was like, well, then it's not your memory.

Come on, man. Like, it's a real easy question.

Speaker 3 I think there's a line in Tom Stoppard's Rosenkrantz and Guildenstern that's exactly around that. Like, what's the first thing you remember? I've forgotten.

Speaker 5

Okay. So building on that last clip.

is another piece. This is literally the next part of this.

We cut it in the middle. So this is the next piece of that.

Speaker 5 This is, again, this is is his proof that he has a birth memory.

Speaker 4 You remember being born? I remember being circumcised. I remember the whole nine.

Speaker 4 And the proof of it was when my wife Mira, that you just met, when she was six months pregnant with my son, Kieran, I wanted to prove to her what I was talking about.

Speaker 4 So I put a light on her stomach every day at six o'clock at night. And I would move that light back and forth and I'd put a song on for a week straight.

Speaker 4

On Saturday, after a week, I didn't put the light there and I didn't do the music. And he pushed up on her stomach.

And then when I put the light there, he started following the light.

Speaker 4 And for the next two months, we did this every night. And he would go all the way around her belly, back and forth, always pushing on it.

Speaker 4 You know, I didn't understand at the time that maybe I've interfered with the development process and maybe he's wrapped the cord around his neck.

Speaker 4

I shouldn't have done all of this, but it came out wonderful and fine. And this little boy, first thing he wanted to do is see light.

He loved lights from that early stage.

Speaker 5 There's a, you know, certainly part of this that feels like you could easily misremember something like this by counting the hits and forgetting the misses, you know, putting a light there and not and nothing happening and then forgetting that that happened, but only remembering if the light was there and then there was a touch underneath.

Speaker 3

Yeah, exactly. You remember the significant things.

You don't

Speaker 3

recall the things that seem insignificant. But like I'm not a pregnancy expert.

I've never had kids. I understand you've never had kids.

Speaker 3 We're probably the worst people to fact check Joe and Terence Howard about what it's like to be pregnant.

Speaker 3 But from what I understand and what I've kind of read around, after about 29 to 31 weeks, somewhere in that kind of area, babies in the womb can respond to changes in light generally.

Speaker 3 There's videos online of people holding a flashlight to pregnancy bumps and watching the baby kick and react.

Speaker 3 I don't know how common that is, how legitimate all those videos are, but conceptually, at least, isn't that much of a surprise?

Speaker 3 I mean, babies, their eyes are developing so that they're useful for when they're born. A strong light is obviously going to make its way through the skin.

Speaker 3 We see that if you hold a flashlight up to your own hand, you can sort of see through a bit.

Speaker 3 And if you're a baby in a dark amniotic sack, even with kind of untested eyes, and it suddenly gets a bit lighter around you, it's not out of the question that you might respond.

Speaker 3

This isn't a sign of something like mysterious and mystical that Terence House has discovered. A lot of people kind of done this.

But sure, once the baby's born, the baby likes light.

Speaker 3

Babies are going to react to light. Their eyes are pretty rubbish to begin with.

They can't focus on things particularly well, so they haven't got a a great sense of vision.

Speaker 3 But light sources, you can't really miss. So babies are going to be mystified by the light.

Speaker 3 So it's not, again, a surprise that he's trained his son to love light and now the baby can see light when it's out.

Speaker 3 These are just normal things that babies do that he's kind of wrapping into this sense of something mystical and otherworldly and insightful.

Speaker 5

Yeah. And very specifically, he starts that whole thing out with, I wanted to prove to my wife that this sort of thing was happening.

So I did this experiment. Well, that it doesn't prove anything.

Speaker 5 What you're saying is that, and if the, and, and at the only, again, the only reason I think to bring this up is to show you what his mind is putting together as what is a proof of something, because it may prove to you that a baby is reacting to stimuli.

Speaker 5 If that was, you know, undertaken in a way that you could actually measure and pay attention to it and you know, record results, et cetera, you might be able to come to a conclusion that the baby is reacting to stimuli.

Speaker 5 But that doesn't mean that the baby's going to remember that stimuli as 57, right? When the baby is 57 years old, is it going to remember

Speaker 5 that this happened at that time? And there's not a proof of that. And so

Speaker 5 I think the reason to talk about this is because his mind is saying, this is what proves this.

Speaker 5 And now for the rest of this episode, we get to hear him make really spurious connections through kinds of different disciplines. the conclusions don't follow.

Speaker 5 So it's something to pay attention to early on. That's why we're we're playing this clip.

Speaker 3 Yeah, we've established what his standard of proof is, and now we'll see where he goes with that standard of proof.

Speaker 5

All right. So, and here's another reason why Terrence believes and is proving to the world that what he's putting out there is true.

He has many patents.

Speaker 4 The proof of it is the 97 patents that I have now. The proof of it is the industries that I've innovated.

Speaker 4 It's like waking up, having a dream that you have a diamond in your hand and out of nowhere, you wake up and you're hoping you're holding it and you try and hold it and it's gone when you wake up.

Speaker 4 But the proof is all the stuff that I've been able to do now.

Speaker 3 So to be clear, patenting something doesn't mean that you've definitely made it work or even that the thing really exists.

Speaker 3 It means that you've had an idea and you can sort of map out how that idea works and you think it's an idea that nobody else has had. Maybe it's an idea no one else has had because it's brilliant.

Speaker 3 Maybe it's an idea that nobody else has had because it's not brilliant. Maybe it could just be terrible, but novel.

Speaker 3 For example, if you just look around the patent system, I found one patent which is for not by by Terence Howard, but as an illustration of what you can patent.

Speaker 3 There's a patent I found for a system of how police could stop cars during a police chase.

Speaker 3 And the patent involves every car in the world being equipped with bullets that are pointing at their own rear tires and then a barcord on the back.

Speaker 3 And then if police scanned the barcord, the car would shoot its own tires out.

Speaker 5 That feels difficult to do during a high-speed chase, but continue. Yeah.

Speaker 3 Now,

Speaker 3 it is a real patent. I would argue it's not evidence of the inventor's genius innovation or how it has revolutionized police safety techniques, but it is a real patent that exists.

Speaker 3 And that inventor can say, I have a patent for it. Yeah.

Speaker 5

Yeah. And I looked up his patents.

You can find them on a link. I'll actually show an image now of one of the patents.

Speaker 5 And it's, he basically has many of them are blocks and shapes with magnets and LED lights, and they vibrate when they're put together.

Speaker 5

And he, throughout this entire episode, is showing different types of shapes. And these shapes mirror those shapes that he's talking about.

And it's what he referred to as a learning tool.

Speaker 5

So he's talking about it as like a child's tool, something that a child could put together. And these are different from sort of just your regular shapes.

They're very fractal looking.

Speaker 5

And so that's the sort of shapes that he created. He also created something we'll mention later.

We'll actually play a clip of this later. This is a virtual environment that he supposedly created.

Speaker 5 And it's for VR that he's, and I'm not going to read the the actual description of this but it's basically a VR room that would react as you move things around in it yeah and that's what he's talking about in terms of having innovated industries he's talking about VR which we will come to and when we come to it you'll see that he hasn't really material materially contributed to how VR works or really how anything real works with those 97 patents yeah and and you know like you suggest there isn't a person at the patent office that is testing your claim there's not somebody you hand a patent to and he says, yep, that's right.

Speaker 5

That's going to work. That goes in the good pile.

They just take your money. So like

Speaker 5

it's not anything at all. So that's something to remember.

He's going to bring up these patents throughout. It doesn't mean anything.

Anybody can get a patent.

Speaker 5 Now he's going to mention a person by the name of John Keeley. This is someone who will come up throughout the entire discussion.

Speaker 4 As I moved along, I got in touch with Michael Hudak.

Speaker 4 He was the president of the University of Science and Philosophy because I was studying a guy named John Keeley, you know, who had worked with frequency back in the 1870s, had built

Speaker 4 the first,

Speaker 4 what do they call it, self-sustaining engine

Speaker 4 back in 1872, but he wouldn't tell people how he built it.

Speaker 4 And I was watching a program with Del Pons, who was, and somebody in the audience said, doesn't John Keeley's work remind you a lot of Walter Russell? And a bell went on.

Speaker 4 And so I got in touch with the University of Science and Philosophy after watching some stuff about Walter Russell. And

Speaker 4

Michael Hudak took me under his wing and started talking to me. But he was more into the philosophy and the love that Walter was talking about.

But my intention was to rebuild the periodic table.

Speaker 3

And he will fulfill that intention. We will come to that as well.

But yeah, he's talking about John Keeley. So who is John Keeley that was such a fascinating person that Terence was studying? Well,

Speaker 3 in the 1870s, John Keeley was an American inventor who invented a machine that he said could run on ether. And ether was at the time believed to be this mysterious substance that

Speaker 3 existed everywhere, that could pass through everything, that wouldn't interact with us, but would allow light to travel from space.

Speaker 3 Because they knew light were waves and they thought that space was a vacuum and they couldn't understand how a wave would move through a vacuum. This is before we discovered radiation.

Speaker 3

So they hypothesized that it wasn't a vacuum. Everything is ether everywhere.

And so John Keeley claimed that this machine that he invented ran on ether.

Speaker 3 He had this machine at his own workshop he showed that he could power it up to more than 10 000 psi just by inputting a little bit of water like a couple of gallons of water and then using some tuning forks to kind of tune that water and from there it would run a generator and it would actually power machinery So just put water in and bang a few tuning forks and you could get a generator running.

Speaker 3 And this was seen to be incredible.

Speaker 3 He got a patron in the form of Clara Jessup Bloomfield Moore, who paid a huge sum for him to continue his work, something like the equivalent of $2 million in today's money.

Speaker 3

But this mortar that he had, it weighed 200 pounds. It ran on nothing but water and tuning forks.

But he claimed it was capable of delivering 10 horsepower of power in 1870.

Speaker 3 So this was quite remarkable. And when he died, people decided to investigate that workshop where this small machine was

Speaker 3

built and where it was housed. And they found how the machine actually worked.

Here's just a quote from Wikipedia. I've got an image that will show you of it.

Speaker 3

But here's a quote. The floors of Keeley's workshop were taken up and a brick wall was removed.

Inside the wall, they found mechanical belts linked to a silent water motor two floors below the lab.

Speaker 3 In the basement, a three-ton sphere of compressed air ran the machines through hidden high-pressure tubes and switches. The walls, ceilings, and even solid beams were found to have concealed tubes.

Speaker 3 Journalists documented everything photographically to leave no room for doubt.

Speaker 3 Two of the people involved in looking into this thought that the tubing and the large steel sphere in the basement indicated the use of regular forces and possibly deception.

Speaker 3 And they said that in their signed statement, Keeley had probably lied and deceived, and they were satisfied that he'd actually used highly compressed air to power his demonstrations.

Speaker 3 So, this wasn't a self-sustaining engine or a perpetual motion machine, as Terence Howis was describing it.

Speaker 3 This was a scam with somebody who'd built a regular machine that was hidden away in order to make it look like he's invented something remarkable.

Speaker 3 And that is one of the foundational pioneering figures on whose work Terence Howis has been following.

Speaker 5 Yeah, it's either that or Big Ether is trying to hide what is

Speaker 5 big ether we think

Speaker 3 anyway.

Speaker 5 Big Ether would be pro, so it would be whatever is opposite of ether.

Speaker 3 It would be anti-movement.

Speaker 5 Anti-ether.

Speaker 5

All right. Now we're going to talk about another couple of people.

This is Einstein and Walter Russell.

Speaker 4 You can go to my in my book. There's a there's a picture of Einstein reading Walter Russell's first book, second book, The Universal One.

Speaker 4 Because when Walter wrote this in 1926, he sent it out to all to 300 different universities and physicists.

Speaker 4 And one of the quotes that Walter Russell said that Einstein says on his deathbed, I should have spent more time reading Walter Russell's work. That's how, and now they're taking it under their wing.

Speaker 3 So again, Walter Russell, one of these figures that he clearly looked up to, based a lot of his work on it.

Speaker 3 Walter Russell was an artist and a sculptor who late in his life, in his 50s, started to decide to revolutionize physics, having no previous experience.

Speaker 3

So the idea that Einstein would like his book so much that he'd be photographed reading it and wish that he'd read more of it was intriguing. So I tried to check this.

I tried to fact check this.

Speaker 3 Now, I could see zero evidence online that Einstein ever said that he wished he'd spent more time reading Walter Russell's work on his deathbed or otherwise.

Speaker 3 Let's give him a bit of leeway and say it wasn't literally on his deathbed, but did Einstein say it? Not that I can see.

Speaker 3 I can find people online claiming that he said it, but everything they're citing is this clip from Joe Rogan as proof, which is kind of why it's worth us looking at Terence Howard's conversation.

Speaker 3 There'll be some things that we talk about that seem incredibly unlikely and maybe even not particularly harmful, but really out there. And you might wonder, why is it worth spending time?

Speaker 3 Well, what I think is interesting is even if Joe Rogan comes away from this conversation thinking, ah, Terence isn't right.

Speaker 3 Clearly, Joe Rogan's fans believe a lot of what Terence has said here or some of it because they're saying Einstein said this about Russell.

Speaker 3 no he didn't that's a great point so what i did find however was a copy of the book that howard was talking about he links to it on his website you can download it skim through the whole thing i had a quick skim through so i found the image that he's referring to so he's he's got a picture of einstein reading a book um as you can see if you go to the show notes or if you go on to uh if you look at this uh on the on youtube you'll see a picture of einstein reading a book and it is next to a picture of Russell's book.

Speaker 3 It's just a meme where it's Einstein holding a book next to a picture of Russell's book next to it in the meme.

Speaker 3

That is it. That is what he's referring to as you can see a picture of Einstein, a fortune of Einstein reading Russell's book.

I can't tell that that's Russell's book. It's just a dark covered book.

Speaker 3 Who knows? Below that image in Howard's book is this meme, well, this evidence rather of Einstein expressing this regret in his deathbed. And that evidence is a meme.

Speaker 3

It is a meme that quotes apparently a book by J.B. Yount, or Junt, who was the biographer of Walter Russell's wife, Lao Russell.

To be clear, Lao Russell was an English lady born Daisy Stebbing, and

Speaker 3 in the 1940s, she decided to take a Chinese name instead. I haven't looked into why, but we can sort of see what's happening here.

Speaker 3 So the excerpt from this biography, it claims that Ben Novik was a very good friend of Einstein's who knew Lao Russell as well.

Speaker 3 And apparently it was Ben who, quote, had confirmed the reports that Lau often heard that Einstein regretted not reading more of Russell's work.

Speaker 3 If I search for any sign that Ben Novik said anything at all about Einstein, I can only find references to Howard's book. So there's not even signs that I could find of

Speaker 3 Ben Novick talking about Einstein.

Speaker 3

Look how far removed we are from the proof now. So Howard said, Einstein read Russell's book and regretted not studying it more.

His source for that is a biography of Russell's widow.

Speaker 3 who told her biographer that her friend had told her that Einstein had told him that he liked her late husband's work.

Speaker 5 Is that six degrees? Yeah, no.

Speaker 3 Therefore, all of physics as we know it is wrong.

Speaker 5 On that bounds,

Speaker 3 we can say, that Russell's work is good and we can carry on. Look at the amount of steps as well that I had to go through here to even understand what Howard was saying and why it was wrong.

Speaker 3

I checked. It took him five seconds to say all that.

And it took me more than 20 minutes to unpack it all. And we'll be touching on what that actually says more in our toolbox section.

Speaker 3 We'll be covering that phenomenon a bit more.

Speaker 3 And I'll also just point out, it's really telling that he describes this as one of the quotes that Einstein said. Because people don't say quotes, they say things that you then quote.

Speaker 3

And I think it's a really minor point. But the thing is, for a lot of people, Einstein has just become this sayer of quotes.

You know, it's Einstein or Mark Twain or Nikolai Tesla.

Speaker 3

These are just people who said quotes. You know, they say things that you come up and quote.

And all of those names, they come up a lot in Howard's world as well.

Speaker 3 But when you actually look into the quotes attributed to lots of these people, you'll find very few of them are things those people actually said.

Speaker 3 So Einstein, in many ways, is kind of an avatar for what you want to be true about the thing that you believe.

Speaker 3 And like I say, even if Joe comes away from this conversation thinking Terrace is completely wrong about all this, his audience don't seem to realize that because they're the ones repeating this Einstein and Russell connection all over the internet.

Speaker 5 Yeah. And the purpose of this is to launder Russell's ideas through someone who has actual physicist cred.

Speaker 5 And the other thing, too, I want to mention is that throughout this, there's a bunch of times that Terrence Howard is suggesting that Einstein is incorrect about many of his theories.

Speaker 5 If that's the case, then why do you care what Einstein had to say anyway? If you thought he was wrong, why even quote him?

Speaker 5 But the reason why is because it's trying to convince people rhetorically that Russell is more important than Einstein, because there's not a physicist out there who would say Russell is more important than Einstein.

Speaker 5

You need to do it rhetorically here. And so that's why he's trying to show you.

And if you look at the two different sort of ideas on physics, if you stack them up,

Speaker 5 Terrence Howard's ideas are a lot closer to Russell's than they would ever be to Einstein.

Speaker 3 Yeah, that's true. And he's also bringing Einstein in specifically with this classic deathbed conversion to say that even at the end, Einstein realized he was wrong and my guy was right.

Speaker 3 So he's even sort of using Einstein to add extra credibility to say that Einstein overthrew his own work in order to follow Russell's here.

Speaker 5 This is the next clip is something I've talked about on the show before. This is Terrence Howard talking about an interaction he had when he handed off a paper to Neil deGrasse Tyson.

Speaker 4 So I reached out to Neil deGrasse Tyson, Neil deGrasse Tyson. I saw him at an event up front, you know, at Fox.

Speaker 4

And he was like, hey, man, yeah, I'd love for you to come on my show, do my radio, do my TV thing. I would love that.

I was like, yeah, but let me, I've got something I want to introduce to you.

Speaker 4

And it was only 36 pages. It was a a treatise.

And I told him it was controversial. And I sent him over that the 36-page thing that had the wave conjugations in it.

Speaker 4 But I started it off with one times one equaling two.

Speaker 4 And he went in on my treatise, wrote, redlined everything.

Speaker 4 You attacked that immediate, that I talked about Walter Russell and Victor Schauberger and John Keeley and Tesla as the people that I looked up to. He attacked them.

Speaker 4 But then he started attacking, you know, the one times one equaling two.

Speaker 5 How did he attack them?

Speaker 5 And they go into it a little bit, but I just wanted to play this clip so people could, if they wanted to, there's a full video on this. It's 18 minutes long, but it is definitely worth your time.

Speaker 5 It's Neil deGrasse Tyson breaking down the paper he got, the interaction they had, what he did with that paper. And really, Neil deGrasse Tyson is

Speaker 5 treating this as if a colleague were to give him a paper and before they submitted it, they would hand it to Neil, who would then look at it,

Speaker 5 red pen it, mark up the things that they know for sure aren't true or that are not following through the text.

Speaker 5 And then they would hand it back and say, Fix this stuff before you send it off to the journal, because the editor is just going to do what I did and send it back to you. So fix it beforehand.

Speaker 5

And so that's what he did. And this is actually a really genuinely nice thing for somebody to do.

The problem is, is Terrence Howard is not a scientist. So he sees it as trashing.

Speaker 5

He sees it as going off on. He sees it as attacking him, but it's not.

It's just someone who is taking the care to correct his work so that he can then build on this thing.

Speaker 5 And in the in the video, you can hear Neil deGrasse Tyson talk about this and talk about how

Speaker 5 important it was for him to

Speaker 5 help nurture this spark in Terrence by giving him what he would give any other physicist.

Speaker 5 And I think that that's like understand that while he is not taking it well, I think that it was, it was delivered in a way that I think was, it was not as, as vicious as Terrence portrays it.

Speaker 3 Yeah.

Speaker 3 And I think it's evidence that Terrence comes not from a research culture where you're trying to check if you're right and spot your mistakes, but from a maybe a place where he's surrounded by people who are just going to say yes to him and follow what he's saying and then spend money on animations and product designs and patents rather than checking what's true or not.

Speaker 5

All right. So now we get to one of the main points of this entire episode.

We're going to get into what I call math and what Marsh calls maths. And it's one times one equals two.

Speaker 4 How is it that multiplication, if it means to make more and increase a number, how is one times one equaling one part of the multiplication tape? Now, I understand it if you're seeing it one time.

Speaker 4

Right. But we call that once.

But the moment that you had that, add the times in there, that multiplicative indicator, that means there's more than one So now each equation is supposed to be balanced.

Speaker 4 You know that equal sign is supposed to show that there's a balance between these two numbers over here and a balance on this one over here. What happened to the other one in this equation?

Speaker 3 It does not it didn't equate So he's saying he doesn't know how math works So basically, yeah, and I think it's important to touch on this briefly because this got a lot of play at the time.

Speaker 3 This was kind of all over the internet

Speaker 3 What's happened is he's got a very faulty initial assumption because he's assuming that to multiply something always means to make it bigger, which is true of a lot of the numbers that we encounter in daily life because typically we deal in whole numbers.

Speaker 3 You know, you've got an apple or a book or a car. You haven't got negative apple and

Speaker 3

a fifth of a book, fifth of a car. So we can picture what a multiple of apples would look like.

It would look like more apples.

Speaker 3 But of course, there are negative numbers, which we can actually easily put in terms that Terence would get if you kind of try and work around the concept a little bit more.

Speaker 3 Terence, for example, could make a bet with a friend for $5

Speaker 3 and then lose that bet and he's down $5. He's got negative $5.

Speaker 3 But if he made that bet with three different friends, so three times, he'd lose three lots of five and his bank balance would be down by negative $15.

Speaker 3

So the amount of money he'd have would get smaller because of the magnification. The magnification would have made it smaller.

And then obviously there's fractions.

Speaker 3 Again, we can put that in terms that people could understand. You've got 20 grapes and you eat half of them or 50%.

Speaker 3

The number of grapes that you've eaten is 20 multiplied by half, which is a smaller number than 20. It's 10.

So you can multiply things and make them smaller here.

Speaker 5 So, so what are you saying then?

Speaker 3

I'm saying he doesn't know how maths works. Yeah.

Okay.

Speaker 5

All right. Okay.

Okay. All right.

Speaker 5

All right. So now we're going to talk about, we're going to shift back to Neil deGrasse Tyson.

And then he's also going to talk a little bit about astrophysics here.

Speaker 6 The Neil deGrasse Tyson thing is so confusing to me that he, so he was critical of Tesla.

Speaker 4

He was critical of Tesla. He was critical of Walter Russell, and he was critical of John Keeley.

But

Speaker 5 this is not his field of study, though, right?

Speaker 4 No, he's astrophysicist.

Speaker 4 He's an astrophysicist, but Walter Russell talked about that the Earth, Walter Russell talked about the fact that the Sun gave birth to the Earth, that it didn't coalesce from some field.

Speaker 4 And the proof of this. Do you guys know that the Earth is drifting away from the Sun?

Speaker 5 Yeah, slightly.

Speaker 4 This is a mistake I made at the Oxford

Speaker 4 because they wouldn't allow me to bring my notes or anything. So I said

Speaker 4 the drift was six inches a year. It's 0.6 inches a year.

Speaker 4 So if you add up how long it would take the Earth to move, and all of the planets in every solar system is drifting away from their primary at this same exact rate, like

Speaker 4 1.5 centimeters. So this is a universal expansion that's happening with everything moving away.

Speaker 5 Okay, I want to touch on just the field of study comment he makes because what I think Joe is trying to do is defend Terrence. Joe is saying, well, it's not his field of study.

Speaker 5 Why is he commenting on this sort of thing? And I think it's, you know, this is the problem is that he's getting really fundamental things wrong.

Speaker 5 And he's basing his work off of people who have been, who are not

Speaker 5 credited with anything really that they've actually discovered. They just had ideas in the sort of astrophysics realm or in the physics realm, and none of those ideas panned out experimentally.

Speaker 5 So I think what he's saying is, is if you're basing your stuff off of these already known things that are known not to create a good result, then perhaps you should rethink much of what you're doing.

Speaker 5 And I think like it's not hard to be out of maybe your field of study a little bit if you're talking about math and you're a physicist.

Speaker 5 You don't have to be an oncologist to know that eating 50 grilled cheese a day isn't a cure for cancer, right?

Speaker 5 And in the same, in the same vein, thinking that certain things that have not shown any evidence for them to be true, saying that stuff doesn't appear to be true isn't a stretch of any kind.

Speaker 3 Yeah, I think that's true. And I think, again, if we look at what Joe is doing here, I think you're absolutely right that he's trying to say, well, why is Neil deGrasse Tyson getting involved?

Speaker 3 It's not his field. Neil deGrasse Tyson isn't an expert in this kind of area.

Speaker 3 But Walter Russell was primarily an impressionist painter and sculptor until his 50s when he started writing about this new concept of the universe.

Speaker 3 Terrence Howard is an actor who's now telling you he's reinvented maths and reinvented the periodic table. So, why is staying in your lane important only when you disagree with Joe Rogan?

Speaker 3 How come Neil deGrasse Tyson isn't a free-thinking intellectual maverick when he's talking about a topic outside of his field?

Speaker 5

That's a really good point, Marsh. Really good point.

A little intellectual consistency would go a long way here.

Speaker 5 Now, we're going to move on to

Speaker 5 more math. This is a bunch of different numbers that he's talking about about and adding things up.

Speaker 4

So this is the math. This is the math.

So it would, so

Speaker 4 5,280 feet in a mile, 12 inches in a foot. Therefore,

Speaker 4 it's 60, one mile equals 63,360 inches. So the number of years that it will take for the Earth to move one mile is 105,600 years.

Speaker 4 So in order for the Earth to reach where we are at 93 million miles, it would take 9,820,800,000,000,000 years for the Earth to get here.

Speaker 4 Likewise, Mars at 147 million miles away from the Sun, it would take 15,780,480,000,000 years for Mars to get where it was. So at a given point, Mars was here in the Goldilocks zone.

Speaker 4 And now Venus is going to inherit the Goldilocks zone next. The Sun will get, Mercury is under a higher pressure because they're still under the

Speaker 4

mistake thinking that there's a void in space. So they forget that mercury is under the highest pressure possible.

So it can't expand. It's like hydrogen.

It's like those octaves before hydrogen.

Speaker 4 So the atmosphere, the iron isn't able to release any oxygen and the oxides.

Speaker 5 Okay, so this is just a, this is why Neil deGrasse Tyson is commenting on this. It's a fundamental misunderstanding of how astronomy and how planets are formed.

Speaker 5 They're not birthed by the sun.

Speaker 5 They're created when an explosion happens and then there's dust in certain areas and then they're created in the areas where that dust coalesces. So that happens to be out where we are.

Speaker 5 The idea that they would travel 1.5 centimeters a year from the sun doesn't make any sense because the sun is only 4 billion years old.

Speaker 3

Yeah, I think that's true. It's funny.

I hadn't really sort of fully grasped what he was saying.

Speaker 3 And partly because he's throwing around so many different numbers that it's genuinely difficult in this part of the conversation to follow exactly what his argument is.

Speaker 3 But his argument is that everything everything starts at the sun and goes outwards. And you're right, that's not where planets come from.

Speaker 3 Other planets, I believe, can enter from outside the solar system, ejected by explosions elsewhere, and can be pulled into the gravitational pole of our sun and can end up in

Speaker 3 an orbital path, depending on their angle of kind of entry.

Speaker 3

But that relies on gravity. And of course, what Terence doesn't believe in is gravity.

So

Speaker 3 all of his constant speeds and things that he's talking about are off by a bit because of gravity. Listening to it again, it's funny how much it reminded me.

Speaker 3 I went to, in 2018, I was undercover at the Flat Earth Conference in the UK in Birmingham, and I saw a speaker speak for three hours about the shape of the Earth being a cosmic egg.

Speaker 3 And what he was saying was very similar, but instead of planets being sort of birthed out of the sun, it was landmasses being birthed out of the Arctic Circle, pushing everything else out.

Speaker 3 And he was even saying about how every layer of this different part of the world had its own sun and moon, and that Mercury and Venus were in the sun and moon position for the furthest in ring.

Speaker 3 But when a new ring is released from the Arctic Circle, everything gets pushed out concentrically, and the planets that were the sun and moon become just external planets while new sun and moons be.

Speaker 3 And it just occurred to me how similar that is to what Terence Howard is suggesting here.

Speaker 3 Like, Martin Kenny, that I saw speaking at this conference, he was saying it about the Earth, but it seems like Terence Howard is picking on similar ideas, but just doing it at a one stage up.

Speaker 3 And it's the sun that's birthing this stuff.

Speaker 5 It's flat universe.

Speaker 3 Yeah, it really is. It really is.

Speaker 5

Wow. Wow.

That's really interesting. And this whole argument that he's talking about is

Speaker 5 much of what he spends his time on and a lot of what their video that they spend their time on, because he's talking about how the sun is the creator of that pressure.

Speaker 5 And that pressure is what creates the worlds and the atmospheres around those worlds, which is why there's gaseous planets out in the farthest reaches of our solar system and there's rocky planets planets in the center of our solar system.

Speaker 5 And so that's what his hypothesis is, is that

Speaker 5

there's no vacuum in space. It's a pressure system.

So that's what he talks about throughout, which is completely provably false.

Speaker 5 Like, I mean, it's like 100% provably false, but that's what Terrence believes.

Speaker 3 Yeah, he's trying to

Speaker 3 do all that in order to replace gravity as a fundamental force, which he's just not accepting.

Speaker 5 Now the next one is talking about how planets are formed.

Speaker 6 Before we do that, can you tell me how a planet is formed under this theory? So, you have a sun, and how does the sun give birth to these planets?

Speaker 4 The same way we defecate and have gas, like Jupiter's,

Speaker 4

that red spot on Jupiter, that's spinning on it, that's going to become a moon. It may take a billion or two billion years.

That will ultimately become a moon off of Jupiter. Where is it?

Speaker 4

Right at the equator. Where do we discharge it? Right at our equator.

And then it will rotate its way around and slowly be pushed out by the solar wind of, well, by Jupiter.

Speaker 6 So like coronal mass ejections.

Speaker 4 Coronal mass ejections.

Speaker 6 So some kind of ejection of matter leaves the Sun, and over billions and billions of years, enough of it collects, and there's enough of a force.

Speaker 4 To where ultimately... that coalescing idea that they have,

Speaker 4 that's where it happens. It's not from materials that's just been left over from the Big Bang.

Speaker 4 You know, like Rupert Sheldrick, Sheld Sheldrick says, you know, the physicists of the day asked for, you give us one miracle and, you know, show us how everything came from nothing and we'll explain everything else.

Speaker 4 And they can't explain everything else.

Speaker 3 I just want to say just briefly here, we often don't give Joe credit where he may be due it. I actually think he's doing a reasonably good job of trying to get clarity here.

Speaker 3 He's asking very specific questions. Could you tell me this? Could you elaborate on this? This isn't too bad.

Speaker 3 So we should actually give credit to Joe for trying to ask some decent follow-up questions in this.

Speaker 5 Yeah, and this is something he clearly knows about, right? Because he's mentioning things that

Speaker 5 i think he probably understands or at least has watched as many youtube videos as i have about astronomy so he understands sort of the very basics of how planets are formed and so he's trying to push and trying to understand what terence believes um you just want to point out a couple of things that terrence says here it's not the the the spot is not right at the equator on jupiter it is below the equator it's right the equator is where most of the fastest currents are on jupiter and so it's below it so again it's it's just not what he's suggesting.

Speaker 5 If you look at it, it is not in the center of the planet. And I mean,

Speaker 5 should we believe someone who thinks that because we human beings poop out of our midsection, that all planets poop out of their midsection?

Speaker 5 I mean, it feels like a, like when you hear this out loud, you have to think like, why are we listening to this person?

Speaker 5 Why is this, this person getting a platform that has, you said 11 million people listen to it. And, you know,

Speaker 5 you and I can hear this and say, okay, well, much of what he's going to say now at this point, I'm not going to listen to or at least pay deep attention to. But what if I miss this part of Joe's?

Speaker 5 Joe's show's three hours long. What if I miss this part? What if I come in later? What if I wasn't, what if I was zoned out at this point?

Speaker 5 What if I was zoned out at some of these really important points where he's saying something really obviously untrue and that most people would look at and say, okay, no, that's just ridiculous.

Speaker 5 What if they're zoned out at that point? And then they do hear this other stuff about Russell and Einstein and other places. And then they repeat that stuff.

Speaker 5 that's the real problem with what joe is putting out there there's no i mean even though he is doing what you suggest which is pushing back a little he's not correcting it all he's not saying well that doesn't make any sense and that's not uh that's not how anybody else thinks how the universe works yeah no i completely agree i also again it's worth pointing out that terrence howard is uh is citing rupert sheldrake here and i didn't expect rupert sheldrake to become a recurring character on this show but no we talk about him in the telepathy tapes i suspect it's not the last time we'll come across rupert Sheldrick.

Speaker 3 So these same, these same kind of coterie of characters keep circling back to the surface as to be the reliable people to cite when you're getting rid of the

Speaker 3 mainstream academics who disagree with you.

Speaker 5 Okay, so we're going to shift back to talk about patents. This is where Terrence describes one of his patents in detail.

Speaker 5

And I did cut a piece of this out because it's literally just Joe reading the patent. And if you want to read the patent, you can go to our show notes, click on it.

It's right there.

Speaker 5 But we're not going to play Joe reading the patent out loud.

Speaker 4 So you're going to look over to, you'll see my name, inventor, Terrence Deshaun Howard, worldwide application. And let's just read the abstract just so they go.

Speaker 6 System and method for merging virtual reality and reality.

Speaker 4 Scroll it so I can see it.

Speaker 6 To provide an enhanced sensory experience. A system and method of merging virtual reality sensory detail from a remote site into a room environment at a local site.

Speaker 4 Now you see it. This is all you.

Speaker 5

Look, look at the inventor. Go back.

Go up a little bit.

Speaker 4

Slido says Terrence Deshaun Howard. Yeah.

Worldwide patent 2010. It was abandoned.

Now go to Cited By. You see that 131, Cited By.

Tap on there. It's right under where it says abandoned.

Speaker 4 Yep, heightened patent.

Speaker 6 Cited by 31.

Speaker 4

Cited by 31. It's to the right.

Yep, right there.

Speaker 5 Tap on there.

Speaker 4

And look at all the companies. And if you look at the patent, these companies have all earned, they have multi-billion dollar companies they've built off of my patent.

Just roll through.

Speaker 5

Sony, Microsoft, Amazon, Hewlett-Packard. Yeah.

Keep going. Keep going.

Speaker 4

Keep going. IBM, and it's still making money.

This patent has earned over $7 trillion.

Speaker 5 They got $7 trillion, but they only got 1.5 centimeters a year. So it takes a really long time to get that $7 trillion.

Speaker 3 So obviously, this is a pretty kind of big claim here.

Speaker 3 First of all, you could say that even if Sony and Microsoft and Amazon and Hewlett-Packard were citing

Speaker 3 his work and were using his work, it's hard to say that they've earned over $7 trillion off his work because prior to him filing this patent in 2013,

Speaker 3

Microsoft already existed. Sony already existed and was already pretty rich.

So it's not true to say that all of their wealth is based on this patent. Right.

Speaker 3 But it's also not true to say that their wealth at all really is based on this patent.

Speaker 3 So first of all, you can go to Snorpes, you can see here that Howard did file a patent application related to this AR and VR technology in 2010, but he abandoned that application in 2013.

Speaker 3

So he doesn't actually get this patent. He never had it.

He never sort of followed it through. I did actually look around for somebody else who are familiar with how patents work writing about this.

Speaker 3 I can see there's a post on Medium from a guy called Robert Rice, who is quite interesting. I'll put a link in the show notes here.

Speaker 3 But he writes out that it should be pointed out that citing prior patent applications, such as Howard's, doesn't mean that a potential patent holder agrees with or finds value in that patent.

Speaker 3 It simply shows that the applicant is aware of that patent and has considered their relevance, which can make the new application stronger and more credible.

Speaker 3 So you could cite something, essentially, this is me saying this now, not a court, you could cite something to say, I've done something in this area.

Speaker 3 Other people have tried to do stuff in this area that wouldn't work for these reasons. See, for example, Howard's patent, but mine overcomes that issue for these reasons here.

Speaker 3 So, you can actually, so don't reject me for the, for the reason they got rejected because I've dealt with that here.

Speaker 3 So, you can actually use the prior applications that got abandoned or rejected or even accepted but were flawed to improve on what you're doing, as long as you're pointing out that you know that they existed.

Speaker 3 And you can even highlight

Speaker 3 where you differ from them sufficiently. So, the the fact that it was cited 31 times doesn't mean they're using his technology.

Speaker 3 It might mean that they've just done a patent search for anyone else who said stuff about this technology and said, we've reviewed all of these patents and we still think ours is sufficiently novel to deserve a patent.

Speaker 3

Also, Terrence Howells, he did file this patent application. It was never granted.

It was effectively rejected outright due to an existing patent covering the same material.

Speaker 3 That patent was marked as abandoned, not because he didn't want to pay the additional fees, but rather because he chose not to respond to the office action rejection.

Speaker 3 Not that there was much room left for him to make his case to get around the rejection.

Speaker 3 So he said he abandoned it because it was too expensive to pay the fees and he didn't want the hassle of the admin, et cetera. But in reality,

Speaker 3 at least according to

Speaker 3 this claim here on Medium, it was rejected and didn't leave much wiggle room. And so he didn't bother responding to the rejection as a result.

Speaker 5 Next clip is talking about a lot of math and a visit to Oxford.

Speaker 6 How many people have you? I know you spoke spoke at Oxford about this, but you didn't speak. Yeah, no, they didn't.

Speaker 4 Oxford did something that broke my heart. Five minutes before the presentation, they wouldn't allow me to have a screen and show and show my proof.

Speaker 5 Why?

Speaker 4

Oh, their computer was down. And I was like, well, you can use my computer.

No, we have sensitive things attached to it. You know, I just need the projector.

Speaker 4 I don't need anything else because they just, they didn't want me to go and talk about this. And that's why I went out there and said, hey, pull out your calculator.

Speaker 4

I talked about acting for a couple of minutes, for 20 minutes. And then I was like, pull out your calculator.

And I want you to enter the square root of 2 in there.

Speaker 4 And let's walk through this loop that is the square root of 2. I was like, let's walk through this, where the square root of 2 cubed is the same value as the square root of 2 times 2.

Speaker 4

And then when you divide it by 2 and cube it again, you get back to the... you take the square root of 2, 1.414, 2135, 62373095.

You cube it, it's 2.828, 4271, 21, 74, 61, 90.

Speaker 4

Divide it by 2, it gets back to 1.414. Cube it again is back to 2.828.

Divided by two, back to 1.414. Here we're making, here we're taking one, two, three big steps.

Speaker 4 We're dividing it by two, and we get back to the same value as we had in the very beginning.

Speaker 5 I'm going to touch on, I'm going to let Marsh handle the math on this, but I am going to touch on what Joe talks about in the beginning, because Joe starts out this clip by saying, you spoke at Oxford.

Speaker 5 And then.

Speaker 5 Terrence responds with what happened at Oxford. They didn't want to give him a computer, et cetera, et cetera.

Speaker 5 And throughout this whole episode, Joe spends much of his time talking about how no one is taking Howard seriously at all because he's an actor first.

Speaker 5 And now he's venturing out into this mathematical and physics and engineering territory. And no one is taking him seriously because they just think of him as an actor.

Speaker 5 But in reality, multiple times, Terrence Howard has used his acting background to

Speaker 5

open doors to get this very idea out there. He tried it with Neil deGrasse Tyson.

If you listen to that clip, I ran into Neil deGrasse Tyson. I wanted to talk to him about this physics stuff.

Speaker 5

Neil deGrasse Tyson wanted to talk to him about his acting stuff. So the description of the video, I found this video.

You can find it.

Speaker 5

You can watch this full address, his full address at Oxford Union. I'll get to what Oxford Union is in a second.

I want to talk about what they say.

Speaker 5 I'm not going to read the whole thing, but they basically say in this, in this YouTube description, and you could go check it out for yourself, they basically say, His acting CV.

Speaker 5 There's nothing in it whatsoever about

Speaker 5

what his physics ideas are or his mathematics ideas are. He was invited as an actor to speak to a group of students.

Now, this is the Oxford Union, not Oxford University.

Speaker 5 So he's not being asked by the physics department to come in and give a talk. The Oxford Union Society is a

Speaker 5 group of students.

Speaker 5 It's a group whose membership is primarily drawn from University of Oxford, but it exists independently from the university. And they, you know, it's also very distinct from the Oxford Student Union.

Speaker 5 So it's not actually part of Oxford University, though many people who go to Oxford University are part of this group.

Speaker 5 But I, but the, the entire, the entire endeavor is come here and talk about your acting.

Speaker 5 And he even admits, I talked about it for 20 minutes and then I started talking about this other stuff because that's what they expected from him. So he's opening doors using his popularity in acting.

Speaker 5

And Joe is treating this throughout the entire episode as that is the detriment that's holding him back. And I would say it's not.

I say that the the thing is propelling this idea forward.

Speaker 3 Yeah, I mean, he wouldn't be on the Joe Rogan show talking about his physics ideas if he was an actor.

Speaker 3 Maybe actually, maybe Joe Rogan would have him on. Yeah, maybe Joe's the one exception.

Speaker 5 I know that's true, Marsh.

Speaker 3

Yeah, you're absolutely right about the Oxford Union. I didn't pick up on that at the time.

But yeah, I mean, the Oxford Union is a debating society.

Speaker 3 They will often have unusual people come to speak and sometimes even quite controversial people. Like they had Tommy Robinson, the far-right activist, come and do a debate at Oxford Union.

Speaker 3 That wasn't Oxford University. It was this debating society for students to get together and have a drink and have this kind of weird conversation that's kind of going on.

Speaker 3 But still, let's do the maths because in another part of my part of my current career, I occasionally do some maths tutoring. So I'm used to showing some equations and stuff at the moment.

Speaker 3

So he is making the maths here sound way more complicated than it is. You know, he's talking about the square root of 2 cubed.

Well, 2 cubed is also called 8. Because obviously

Speaker 3

he's squaring it, he's cubing it, he's going around, he's saying, it's weird how these numbers keep coming back to each other. It's not weird at all.

It's just maths and the way that maths is written.

Speaker 3 So 2 cubed is also called 8, which you could write as 2 times 2 times 2. If you wanted the square of that, you could do the square of 2 times 2 times 2, or you could notice that 2 times 2 is 4.

Speaker 3 So we're looking at the square root of 4 times the square root of 2, and that's the same as the square root of 8. It's also the same as saying, you know, we know that the square root of 4 is 2.

Speaker 3

So we know that what we've got now is the square root of eight is two times the square root of two. None of this is mystical.

None of this is mysterious. None of this is like mind-blowing.

Speaker 3 This is just regular maths. You can write stuff down in different ways.

Speaker 3 It's the strength of maths that allows you to express things in different ways and then do different things to them based on the way that you've expressed them.

Speaker 3 None of this certainly is, quote, a lie they've fostered for so long. Yeah.

Speaker 3 So it's just bringing this conspiratorial aspect in, but showing he just doesn't understand the fundamentals of maths as to why these principles, why those numbers end up the same if you manipulate them in the way that he was doing.

Speaker 5 And the way he presents it, just like you suggest there when you say the lie they fostered for so long, is Oxford is trying to repress this information because they won't give him a link to the HDMI so that he could plug his computer in when really they just wanted him to talk about acting.

Speaker 5 And there's no reason to be a, no reason to bring a PowerPoint for that. We could just talk about acting without that.

Speaker 3 Yeah. But every tech issue he experiences is

Speaker 3 they trying to silence him.

Speaker 5 I will say that there is going to be many tech issues later and in the gloves off section where we talk about how they are trying to silence him.

Speaker 5 Okay, now we're moving on to the discussion about straight lines.

Speaker 6 Is it because we can create straight lines that we get confused?

Speaker 4 We can't create it because even when you look at it under an electron microscope, you'll see all the little curved dots that make it up.

Speaker 4

There are no straight lines. Like if you look at it, even in a box.

If you looked at this, you'll say, oh, that's a square right there, right in the middle. Sure.

Speaker 4 You'll see that square happening right there.

Speaker 4 But if you look at it from the side, from its real perspective, you see that it's not. The straight lines are an illusion.

Speaker 4 Again, we are being fooled by our senses because there is no motion in the straight line. So all these homes that they're building, and they keep wondering, why do they keep blowing over?

Speaker 4 Why don't you make the homes look like a mushroom? Follow the curvature of nature, and you won't have to worry about rebuilding them in hurricane zones or in tornado zones.

Speaker 5 I live in this tornado zone, but I don't want to live in a mushroom.

Speaker 5 I just don't want to.

Speaker 3

It could be adorable. You can get yourself little hats.

You could be like like a little gnome.

Speaker 5

I'll fish and roll. So many gnomes.

So many gnomes.

Speaker 3 Look, he's right that you might not be able to draw a measurably straight line with your pen, even with a ruler, even if you're incredibly accurate.

Speaker 3 You know, you zoom right in, you're going to be able to see that it's not perfectly straight just because of the nature of drawing. But you can hypothesize a straight line pretty easily.

Speaker 3 If you say, for example, imagine a perfect square where all four sides are parallel and there's 90 degree, exactly 90 degrees at each corner.

Speaker 3 You can hypothesize that you can conceptualize that that has to have straight lines because straight lines are an are an inevitable consequence of the thing you just described there we can draw a good approximation of that square on paper it won't be perfect it'll be as close you can get but the concept of it is still a straight line we can also express a straight line mathematically if you want to draw a straight line okay plot a graph plotting the function x equals y.

Speaker 3 That necessarily has to be a straight line because for every measurement you go along the x-axis, you also go up the y-axis. So one is going to be one and two is going to be two.

Speaker 3

And you're always going to draw a straight line. There is no way to fulfill that function except with a perfectly, literally perfectly straight line.

So you can do straight lines.

Speaker 3 We just have to be a bit more conceptual about it.

Speaker 3 And I think that's interesting because elsewhere in this conversation, he actually spends a lot of time talking about the platonic forms, the platonic solids. And we'll even see that.

Speaker 3

We'll cover that in the toolbox. But he doesn't seem to accept that perfect shapes can exist hypothetically, which is what the the platonic forms are about.

But they can.

Speaker 3

All you have to hypothesize, just hypothetically imagine, conceptualize a square. And there you go.

There's actually straight lines. It has to be.

Speaker 5 And Terrence is talking about this because his whole idea, the bigger idea here is that humanity is stuck in

Speaker 5 this sort of rut.

Speaker 5 We are in this platonic universe that has been sort of imposed upon us by the ancient people who say that squares and triangles and dodecahedrons is what's what it is and he's saying it's all curves he's like no no no it's all curves and you should follow what nature has that's all curves well just to get back to the practical side of this joe actually it to his credit rightfully mentions right after this clip that it costs more to make a mushroom shape and an organic shape it just costs more to do that and he doesn't mention this but we also have standardized furniture for a box because that's what we've been using for a long time is a box so him saying well we should just follow these things well it's not practical to do that.

Speaker 5 It's not that we're just hindered by our platonic ideals, it's that we just sometimes look at things for their practicality, and it's not practical to make a bunch of mushroom houses.

Speaker 3

Yeah, absolutely. I hate wallpapering.

I especially would hate wallpapering a mushroom shape.

Speaker 5 That would be a nightmare.

Speaker 3 How are you going to put pictures up as well? If you've got a curved wall, how are you going to get a picture?

Speaker 5

Yeah, everything's kind of hanging all weird, and yeah, it really is not a great idea. All right, uh, last clip in the main event segment.

This is talking about the universe.

Speaker 4

Because of the Michelson-Morley experiment in 1887, and because special relativity took off. And that meant, oh, everything is dead.

So we have no responsibility to anything.

Speaker 4

Everything is happenstance. We all got here by one big explosion, and therefore life has no purpose.

Nothing has a purpose. And so now we can kill off these things.

Speaker 4 And but they haven't looked at hemoglobin and chlorophyll. They haven't looked and said, okay, wait a minute.

Speaker 4

Let's do the law of similarities of A is equal to B and B is equal to C, then A is equal to C. My view is this.

If you know one thing about one thing, you know one thing about all things.

Speaker 4

Find a common factor and either multiply or divide. That common factor happens to be hydrogen.

Everything in the that we, in the observable universe that we see is 99% hydrogen.

Speaker 4

Well, now we have the geometry of hydrogen. So now we can manipulate 99% of the universe.

And there's nothing we can't accomplish.

Speaker 3 So again, there's so much in there. There's a lot of technical jargon.

Speaker 3 We'll actually come to technical jargon in the toolbox because you can see how it's used here to kind of baffle you from what you're trying to say. But let's just pick up one piece of that.

Speaker 3 He's talking about the Michelson, the Michelson-Morley experiment. So, this was an experiment that was actually designed to try and test that notion of ether that I was talking about earlier.

Speaker 3 So, this idea that there's this infinite substance in the universe that we can't see and doesn't interact with anything, but they did think it conveyed light.

Speaker 3 So, they try to essentially test how light can

Speaker 3 get from the sun by having this experiment to see does light move in waves is there an it we know that light moves in waves is there a a wave form to the ether so does light move at different speeds depending on which direction it's going so if you bounce light around inside of a glass box will it travel faster in one direction than another And if it does, that's indication that when it's traveling in the faster direction, that's kind of going with the wind, with the ether wind.

Speaker 3 They even called it the ether wind. And when it goes slower, it's going upwind.

Speaker 3

They tried all that. There wasn't.

They did the experiment. Light traveled the same speed in the same medium.

And they threw the notion of ether out.

Speaker 3 And a few years later, they discovered radiation and they realized how light can travel.

Speaker 5 I want to talk about something he mentions early on when he mentions hemoglobin and chlorophyll. And he says, if you look at them, they're similar and they don't really spend a lot of time on this.

Speaker 5

And so I did a little bit of looking to see. And he's right.

They are very similar. They have, he does at one point, I think we didn't, we're not going to play the clip, but he says essentially the

Speaker 5 sort of main piece of it or the main piece of the molecule that's sort of holding it all together in one is is one thing and another it's iron, et cetera.

Speaker 5 And he talks about how these things are so similar. Well, we share a common ancestor with plants.

Speaker 5 So it would make sense that something in us matches something in plants, that there is some similarities between the two of us.

Speaker 5 So it's not like it's some sort of big mystery that both hemoglobin and chlorophyll seem to be very similar chemically.

Speaker 5

If you look at the way they're set out, like as a chemical, they look very similar when they sort of diagram them out. And it's because we share common ancestors.

That's just how it works.

Speaker 5 And also, he says a very quick rhetorical thing here that I just want to repeat. He says, if you know one thing about one thing, then you know one thing about all things.

Speaker 5

And it's like, sure, yeah, man, I guess so. because my one is part of that Venn diagram.

Like if I know one thing about one thing, it's still part of that big Venn diagram.

Speaker 5 But just because I know my waist size doesn't help me understand much about the universe except for where I fit. That's all it helps me understand.

Speaker 5

So again, it's like a rhetorical device he's using to make it seem like he's saying something profound. It's not profound.

All right, let's move on to our toolbox section.

Speaker 5 If you thought goldenly breaded McDonald's chicken couldn't get more golden, thank golder because new sweet and smoky special edition gold sauce is here.

Speaker 4 Made for your chicken favorites.

Speaker 3 I participate in McDonald's for a limited time.

Speaker 7 Hey, this is Dan Harris, host of the 10% Happier podcast. I'm here to tell you about a new series we're running this September on 10% Happier.

Speaker 8 The goal is to help you do your life better. The series is called Reset.

Speaker 7 It's all about hitting the reset button.

Speaker 8 in many of the most crucial areas of your life. Each week, we'll tackle a topic like how to reset your nervous system, how to reset your relationships, how to reset your career.