Episode 220: The Zipper

The Memory Palace is a proud member of Radiotopia from PRX. Radiotopia is a collective of independently owned and operated podcasts that’s a part of PRX, a not-for-profit public media company. If you’d like to directly support this show and independent media, you can make a donation at Radiotopia.fm/donate. I have recently launched a newsletter. You can subscribe to it at thememorypalacepodcast.substack.com.

Music

- Swiming by Explosions in the Sky

- Walking Song by Kevin Volans and the Netherlands Wind Ensemble

- I Walk on Guilded Splinters by Johnny Jenkins

- Seduction by the Balanescu Quartet

- Lunette by Les Baxter and Dr. Samuel J. Hoffman

- Running Around by Buddy Ross

- September by Giles Lamb

Notes

- This episode was pieced together from a ton of little fragments but I wanted to steer folks to a couple of resources in particular: this excellent article from a few years back in the Toronto Star by Katie Daubs, and this documentary from filmmaker, Amy Nicholson, that primarily uses the Zipper as a way to talk about changes at Coney Island but has some great details from Harold Chance and his sons.

Learn about your ad choices: dovetail.prx.org/ad-choices

Press play and read along

Transcript

Speaker 1 This episode of The Memory Palace is brought to you by Progressive Insurance. Fiscally responsible, financial geniuses, monetary magicians.

Speaker 1 These are things people say about drivers who switch their car insurance to Progressive and save hundreds. Visit progressive.com to see if you could save.

Speaker 1 Progressive Casualty Insurance Company and affiliates, potential savings will vary, not available in all states or situations.

Speaker 1 This episode of Memory The Palace is brought to you by Life Kit. When you're a kid, you need all sorts of help, learning your ABCs, tying your shoes.

Speaker 1 Then you become a teenager and a young adult, and if you are like I was, you need all sorts of help, but you are hardly asking for or accepting any of it.

Speaker 1 Then you get older, you start looking around and thinking there has got to be a better, or faster, or safer way to do this thing,

Speaker 1 whatever that thing might be. And while you are looking around, you will notice that there's a ton of nonsense,

Speaker 1 a lot of quick fixes, a lot of just mumbo-jumbo.

Speaker 1 But then there's Life Kit, a podcast from NPR, where you can find thoughtful, expert-guided ideas and techniques about tackling issues in this thing we call Life.

Speaker 1 LifeKit delivers strategies to help you make meaningful, sustainable change. And the show is fun.

Speaker 1 You're flipping through episodes and bopping around thinking, yeah, I do kind of want to know what this whole thing is with seed oils and hear from people who really know and sort out the science from the hype.

Speaker 1 And then you put it on and it is delightful and informative. And then you're kind of idly listening to this one about how you can avoid buying counterfeit products online.

Speaker 1 And you're like, Yeah, I do that technique, and yeah, I know that one too, and yeah, sure, that one, I'm no dummy.

Speaker 1 But then you hear a couple more, and you're like, oh, shoot.

Speaker 1

Yeah, I almost fell for that yesterday. And oh, yeah, I need that one for my back pocket.

LifeKit isn't just another podcast about self-improvement, it's about understanding how to live a better life.

Speaker 1 Starting now, listen now to the Life Kit podcast from NPR.

Speaker 1 This is the Memory Memory Palace. I'm Nate Tomeo.

Speaker 1 This one was different.

Speaker 1 You don't know where the ideas come from all the time when part of your job is coming up with ideas. But it seems that one day at work, Joe Brown saw something in a piece of plywood.

Speaker 1 There was something there. Maybe he took it to a table saw and cut out a shape.

Speaker 1 A little different than the ones that folks there at Chance Amusements of Wichita, Kansas typically use when they made their rides.

Speaker 1 A change from those flat bottom circles, the little setting suns that might hang from a Ferris wheel, or if you flip them over, could spin like a teacup.

Speaker 1 He cut out a new shape that looked a bit like an apostrophe, or a particularly cartoony lowercase B, depending on how you oriented it. Hadn't tried a shape like that before.

Speaker 1 Could be something, but how would he attach it? Pictured people sitting in a cart the shape of that piece of wood.

Speaker 1

He picked up a metal rod and placed it to one side behind the imagined backs of the imagined people. That wasn't anything.

That was just another affairs.

Speaker 1 Put the rod on the top, and the cart would swing about a bit. But so what?

Speaker 1 That had been done.

Speaker 1 But then a light bulb went off. One of those blinking carnival light bulbs.

Speaker 1 Maybe one that's fritzing out a bit, maybe making you worry that maybe the carnies aren't really keeping up with maintenance like they should at this carnival.

Speaker 1 Anyway, Joe Brown has an idea.

Speaker 1 He drills a hole in the plywood, just a bit off center, puts the rod through the board and holds onto each end of the rod, and starts to move the model up and around through space. This was something.

Speaker 1 This one was different.

Speaker 1 Harold Chance first found business success helping people take it easy. In the middle of the 1960s, he was America's foremost manufacturer of miniature railroads.

Speaker 1 The tiny engines that pull tiny cars filled with passengers big and small slowly around amusement parks, public gardens, and the occasional sprawling estate.

Speaker 1

But he was born Harold Chance, and one does not waste a last name like that playing it safe all the time. So he bet on excitement.

He purchased the patent for a ride called the Trabant.

Speaker 1 It was his company's first foray into thrill rides. Looked a bit like a teetering roulette wheel that spins and rocks up and down and thrills or nauseates depending on the rider.

Speaker 1 And it was a huge moneymaker. Thanks in large part to Harold Chance's first major contribution to the history of amusements.

Speaker 1 He figured out a way to build the Trabant, sometimes branded as the Wipeout or the Mexican hat.

Speaker 1 He figured out a way to build that ride such that it could be easily disassembled and put onto the back of a single flatbed truck.

Speaker 1 And so now he didn't just have an exciting ride that he could sell to amusement parks, but one he could sell to folks who ran traveling carnivals, who can now take the Trabant with them as they went from town to town.

Speaker 1 The one truck ride. It was a revolution in the business of things that make lots of revolutions.

Speaker 1 So he was very excited to hear that Joe Brown, his plant manager and primary ride designer, had a new one-truck ride to show him.

Speaker 1 There is an interview that Harold Chant sat for not long before his death in 2010 at the age of 88. In it, he remembers the first day he encountered Brown's new ride.

Speaker 1

The day that would change his life. He is pretty nonchalant about it.

He says as the founder of the company, he had to be the first person to test it out.

Speaker 1 He kind of shrugs and says he wouldn't build anything he wouldn't ride.

Speaker 1 But was he that nonchalant at the time?

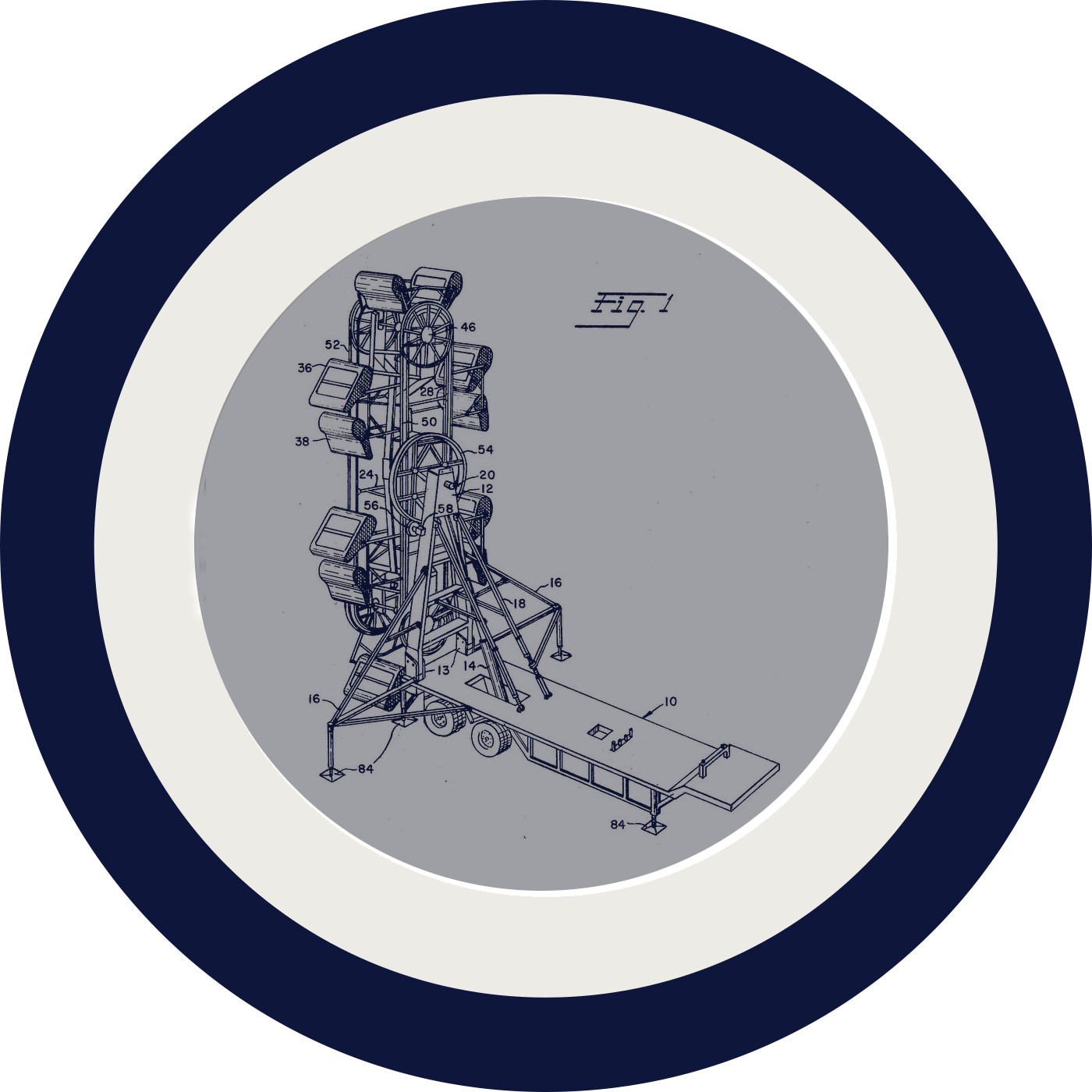

Speaker 1 On that day in 1968, when he first took in the sight of the zipper, rising 57 feet off the ground, a long oblong tower that spins in its center like a Ferris wheel.

Speaker 1 But along its edge run parallel cables that pull a dozen cars carrying two passengers each around that tower, as it turns in the opposite direction.

Speaker 1 And the cars are attached, like Joe Brown's original plywood apostrophes, a bit off-center. So they wobble as they hang there as the ride is loading.

Speaker 1 Rocking back and forth as anxious passengers adjust in their seats and wait for the ride to start spinning. Spinning in three directions at once.

Speaker 1 The tower turning at the center, the carts going around that tower, then each of those carts tumbling and flipping as they go up and over and around and around.

Speaker 1 Harold Chance hopped in.

Speaker 1

Strapped in. And off he went.

The tower whipping around, the carts zipping about the tower, as the whole thing is whipping around. Those carts tumbling, going around and around.

Speaker 1

Harold Chance's little apostrophe cart almost flipping over with all that whipping and zipping. The thing was fast.

It was scary. And it was going to be huge.

Speaker 1 Never again did anyone ride the zipper the way that Harold Chance did that day.

Speaker 1 Turns out that the next time they tested it, they loaded the passenger seats with passenger-sized sandbags and belted them in and turned on the zipper and it zipped and whipped and the cars flipped and the zipper flung those pretend passengers out to smash down in in a cloud of sand when they hit the concrete.

Speaker 1 So they installed a metal cage around each of the carts and the zipper went on sale.

Speaker 1 It was a sensation.

Speaker 1

The carnival operators loved it. One truck, two carneys, two hours, and the zipper would be up and running.

It was new, it was flashy, and it was tall.

Speaker 1

It could be seen for miles, blinking above the treetops or a glow in the fog by the shore. And it was loud.

Not the ride itself, that was just the typical generator hum. It was the screams.

Speaker 1

A siren call across the dirt parking lot. Teens running to try this new monster.

Little kids gawking, wondering if they would be that brave one day.

Speaker 1 Older folks wondering at the way that summers just seemed to slip away. Carneys love the zipper too.

Speaker 1 Because an off-label benefit of all that flipping and spinning was stuff would just rain out of the passengers' pockets as they tumbled through the air.

Speaker 1 Put up the sign that says the management isn't responsible for lost articles, and the Carneys could just rake it in at the end of the night, change by the cupful, lost wallets.

Speaker 1 This became such an added attraction for the Carneys that the folks back at Chance Rides actually changed the spacing in the mesh in the cages so it was big enough to allow coins up to a silver dollar size to slip through.

Speaker 1

But for the riders, it was probably worth it. To say you had dared to ride the zipper.

To have managed to hold on to your lunch, if not your lunch money, to have defied death.

Speaker 1 But not everybody did.

Speaker 1 By the late 1970s, there were 93 zippers operating around North America. Thousands of people riding them each day and night during the fleeting summer carnival season.

Speaker 1 A handful of those riders died.

Speaker 1 After two girls were thrown from two separate rides, one in Arizona, one in Pennsylvania, and killed two weeks apart in the summer of 1977, a congressman tried to ban the zipper.

Speaker 1 The Consumer Product Safety Commission sought an injunction to shut down the ride until a task force, eventually led by the mother of one of those girls, made sure it wouldn't happen again.

Speaker 1 And thanks in large part to her effort,

Speaker 1 the zipper still rises above fields and clearings and church parking lots each summer,

Speaker 1 as it has for more than 50 summers.

Speaker 1 Even as time marches on, as roller coasters get wilder and wilder, adding new thrills, new twists on twists.

Speaker 1

The zipper endures. It is safer now, with latches and locks that can't as easily come undone.

The whole ride spins more slowly than it used to. But it still terrifies.

Speaker 1 The newspaper stories about injuries and deaths, about a possible ban, made the zipper into something of a legend, added to its allure to the kids staring up.

Speaker 1

Maybe thankful that they weren't this tall yet to ride the ride. Not this summer.

Maybe wondering the whole next year whether they could really do it.

Speaker 1

For the teenagers high-fiving, jumping up and down in the Midway Lights, having conquered it. Swearing they weren't scared at all.

You were screaming, they weren't screaming.

Speaker 1 To the dad, wobbling away, having kept a promise, maybe needing to sit down for a minute, but having made a memory that will last a lifetime.

Speaker 1 There is still some summer left.

Speaker 1 This episode of The Memory Palace was written and produced by me, Nate DeMayo, in the summer of 2024. This show gets research assistance from Eliza McGraw.

Speaker 1 It is a proud member of Radiotopia, a network of independent artist-owned and operated listener-supported podcasts from PRX, a not-for-profit public media company.

Speaker 1 If you listen to this show regularly, you know that from time to time I like to shine a little light on one of my fellow Radiotopia shows.

Speaker 1 And today, I want to tell you that if you have not made Song Exploder a regular part of your podcast listening experience, it is time.

Speaker 1 Rishi, the host, and I have been friends for years. We joined the network at the same time, and getting to be in this thing with him has has been one of the great pleasures of my professional life.

Speaker 1 Song Exploder is simply one of the best podcasts that there has ever been. You can listen each episode to artists breaking down a single song, how it started, how they put it together.

Speaker 1 You will be introduced to new artists.

Speaker 1 And then sometimes you will hear a beloved song from your past, like I just look down on my feed and there are the flaming lips talking about how they wrote Do You Realize?, which is one of the best songs there has ever been.

Speaker 1 Learn about Song Exploder and all the Radiotopia podcasts at radiotopia.fm.

Speaker 1 You can learn more about this podcast by following me on Twitter and Facebook at Thememory Palace. On Instagram and threads at thememory palace podcast.

Speaker 1 And on Substack, there's a newsletter at thememorypalaspodcast.substack.com.

Speaker 1 Follow me wherever you'd like to find out more about what's happening with the show, about the Memory Palace book that is coming out on November 19th, 2024 from Random House.

Speaker 1 And you always also welcome to write me an email at nate at thememorypalace.us.

Speaker 1

Just yesterday I got like the nicest emails from a few people who had heard me on an episode of Radiolab, and it was just lovely. It is always nice to hear from folks.

I will talk to you guys again.

Speaker 1 Radiotopia

Speaker 1 from PRX