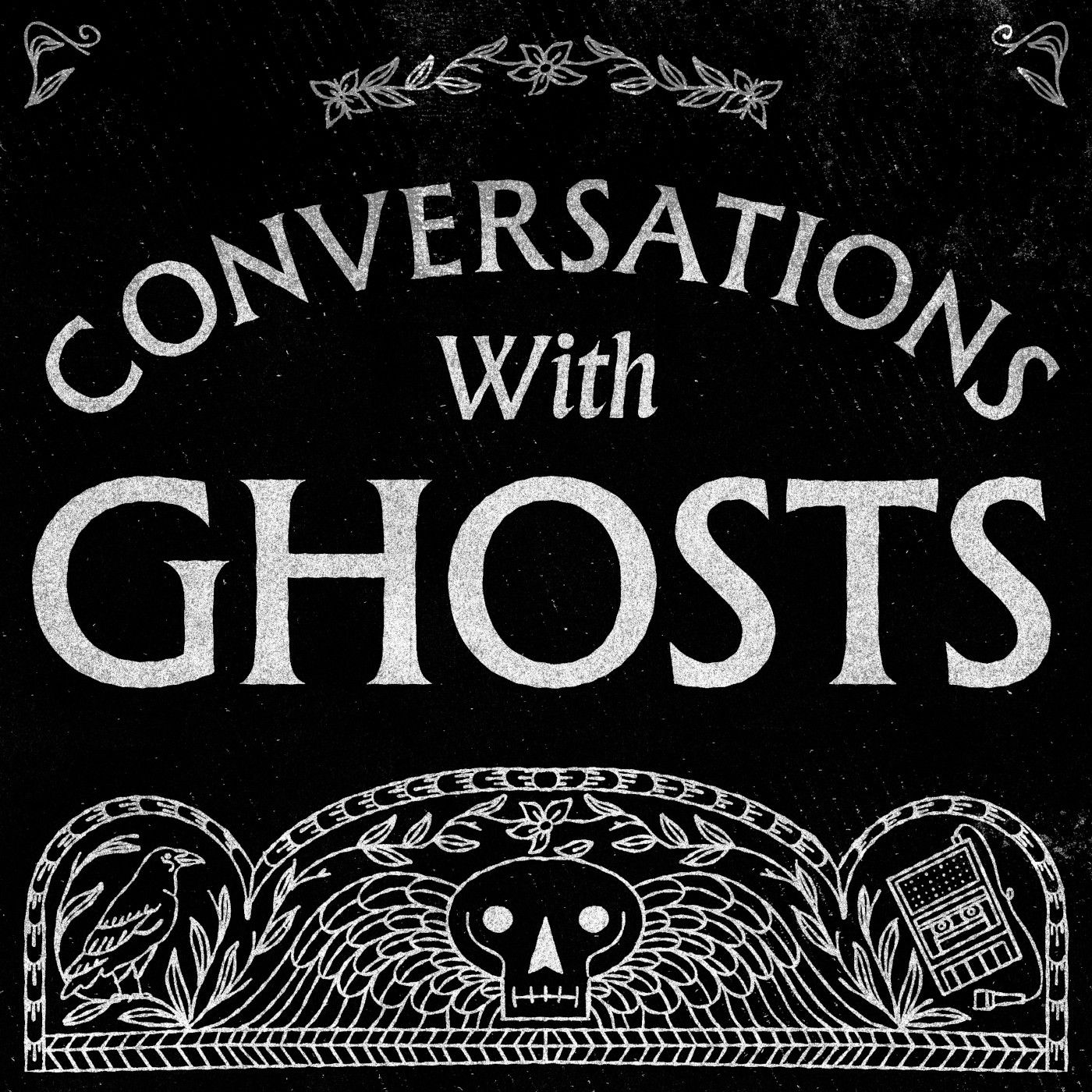

NoSleep Podcast Summer Hiatus 2025 #1

"Dead Man's Hands" written by Andrew McRae (Story starts around 00:01:50)

Produced by: Jesse Cornett

Cast: The Little Man - Graham Rowat, Journalist - Dan Zappulla, Boudreaux - Peter Lewis, Margie - Mary Murphy, Lonnie Fincher - Reagen Tacker, Priest - Jesse Cornett, Lonnie's Mother - Erin Lillis, Mother's Friend - Sarah Thomas, Undertaker - AllontÈ Barakat, Sheriff - Jeff Clement

"The Raven Man" written by Daniel J. Greene (Story starts around 00:45:45)

Produced by: Jesse Cornett

Cast: Narrator - Graham Rowat, Receptionist - Marie Westbrook, Old Woman - Erika Sanderson, Young Cashier - Tanja Milojevic, Bartender - Jake Benson, Bar Patron - David Cummings

Click here to learn more about The NoSleep Podcast team

Executive Producer & Host: David Cummings

Musical score composed by: Brandon Boone

"Summer Hiatus 2025 01" illustration courtesy of Alexandra Cruz

Audio program ©2025 - Creative Reason Media Inc. - All Rights Reserved - No reproduction or use of this content is permitted without the express written consent of Creative Reason Media Inc. The copyrights for each story are held by the respective authors.

Press play and read along

Transcript

Speaker 1 What does Zinn really give you?

Speaker 2 Not just smoke-free nicotine satisfaction, but also real freedom to do more of what you love, when and where you want to do it.

Speaker 1 Why bring Zinn along for the ride?

Speaker 3 Because America's number one nicotine pouch opens up all the possibilities of right now.

Speaker 2 With Zinn, you don't just find freedom, you keep finding it.

Speaker 4 Find your Zin.

Speaker 1 Learn more at Zinn.com.

Speaker 2 Warning, this product contains nicotine.

Speaker 3 Nicotine is an addictive chemical.

Speaker 3

Ah, this is the life. Sun, sand, and surf.

Such a refreshing break from the dark, dank dungeon of the no-sleep universe. Children playing, waves crashing, beach bodies as far as the eye can see.

Speaker 3 My tiny Speedo is a bit snug, but that's alright. People are looking at me with horror in their eyes, but I assume that's because they recognize me as the sleepless podfather.

Speaker 3 And yes, in case you're wondering, I'm David Cummings, and you've joined me for the No Sleep Podcast's Summer Hiatus Volume 1.

Speaker 3 I realize it's not technically summer yet, but when the temperatures rise and the sun shines, you can't help but embrace the season of warmth.

Speaker 3 On our our episode this week, we have two tales for you which were first featured on our Sleepless Sanctuary premium episodes. And, um,

Speaker 5 now where is he?

Speaker 3 I was supposed to be joined by Graham Rowet down the shore here.

Speaker 3

Where could he be? He might be hanging out at the carnival over there. He really does love the carny life.

Or maybe he went for a swim and he's now under the sea.

Speaker 3 Either way, Graham will be leading the stories this week, so keep an ear out for him.

Speaker 3

So enjoy your summer break, as it were. I'll be here all day and night.

Because, as you know, it's always good to be sleepless.

Speaker 6 Lily is a proud partner of the iHeartRadio Music Festival for Lily's duets for Type 2 Diabetes Campaign that celebrates patient stories of support. Share your story at mountjaro.com slash duets.

Speaker 6 Mountjaro terzepatide is an injectable prescription medicine that is used along with diet and exercise to improve blood sugar, glucose in adults with type 2 diabetes mellitus.

Speaker 6 Mount Jaro is not for use in children. Don't take Mount Jaro if you're allergic to it or if you or someone in your family had medullary thyroid cancer or multiple endocrine neoplasia syndrome type 2.

Speaker 6 Stop and call your doctor right away if you have an allergic reaction, a lump or swelling in your neck, severe stomach pain, or vision changes.

Speaker 6 Serious side effects may include inflamed pancreas and gallbladder problems. Taking Manjaro with a sulfinyl norrhea or insulin may cause low blood sugar.

Speaker 6 Tell your doctor if you're nursing, pregnant, plan to be, or taking birth control pills, and before scheduled procedures with anesthesia.

Speaker 6 Side effects include nausea, diarrhea, and vomiting, which can cause dehydration and may cause kidney problems.

Speaker 6 Once-weekly Manjaro is available by prescription only in 2.5, 5, 7.5, 10, 12.5, and 15 milligram per 0.5 milliliter injection.

Speaker 6 Call 1-800-LILLIERX-800-545-5979 or visit mountjaro.lilly.com for the Mountjaro indication and safety summary with warnings. Talk to your doctor for more information about Mountjaro.

Speaker 6 Mountjaro and its delivery device base are registered trademarks owned or licensed by Eli Lilly and Company, its subsidiaries or affiliates.

Speaker 7 Start your journey toward the perfect engagement ring with Yadav, family owned and operated since 1983. We'll pair you with a dedicated expert for a personalized one-on-one experience.

Speaker 7 You'll explore our curated selection of diamonds and gemstones while learning key characteristics to help you make a confident, informed decision.

Speaker 7 Choose from our signature styles or opt for a fully custom design crafted around you.

Speaker 7 Visit yadivejewelry.com and book your appointment today at our new Union Square showroom and mention podcast for an exclusive discount.

Speaker 3

In our first tale, we enter the world of the traveling carnival. The sideshows, the rides, the carnies.

It's a life lived by those who have usually veiled themselves off from the general public.

Speaker 3 But in this tale, shared with us by author Andrew McRae, we meet a journalist who is interviewing a lifelong carny, and the carney has much to share about what goes on behind the scenes.

Speaker 3 Performing this tale are Graham Rowett, Dan Zapula, Peter Lewis, Mary Murphy, Reagan Tacker, Jesse Cornett, Aaron Lillis, Sarah Thomas, Alante Bariquet, and Jeff Clement.

Speaker 3 So get your tickets and roll up to hear the tale of the dead man's hands.

Speaker 4 We sat down to eat at the worn picnic tables the Carneys had set up in the center of their circle of steel wagons, wagons, the airstreams gently rusting in the salty Florida sunshine.

Speaker 4 A man without legs ankled, well, wristed past,

Speaker 4 and another with skin as crinkly as the gators in the swamps played Chinatown my Chinatown on a phonograph.

Speaker 4 Gulls wheeled overhead, squawking for garbage scraps.

Speaker 4 The worn little man across from me chewed the end off of his cigar and spat it on the the ground.

Speaker 8 A retrospective, huh? Can't believe the way I let you newspaper types badger me.

Speaker 4 Guess you need to be better at the cards.

Speaker 8 Well, when do you want me to start?

Speaker 3 Twenty, ten, further back than that, back before McKinley got himself shot. Garfield, too?

Speaker 4 I shrugged.

Speaker 8 Tease, but you're a closed-lipped son of a bitch when you want to be.

Speaker 4 I'd long since learned to just let my interviews unravel themselves.

Speaker 4 I shrugged again.

Speaker 4 The little man reached over and clapped the thunderous buttocks of a large woman in a hibiscus print dress who rippled past us. He had a fake eye, but tipped a wink with his real one as she turned.

Speaker 3 Oh, you.

Speaker 4 She had tin plates clasped in her baseball mitt hands, a rich growth of beard beard obscuring much of her face, aside from the made-up eyes and the rouged lips.

Speaker 4 The little man caught my glance and struck a match on the table.

Speaker 8 Don't ask. Who understands the mysteries of true love, anyway?

Speaker 4 I said nothing and just smiled gently. I wanted to encourage the speaker before me.

Speaker 4 He puffed his cigar alight.

Speaker 8 And don't worry about the mechanics, neither.

Speaker 3 Fair.

Speaker 4 I had been staring at the woman whose pale skin reminded me of a custard, complete with all the folds, divots, and dimples you'd find in a bowl of the stuff in your mother's kitchen.

Speaker 4 And I had been trying to do the math on the whole shebang.

Speaker 4 You worked with a lot of circuses over the years?

Speaker 8

Carnivals, sure. Not so many circuses.

Never been that classy. Or lucky.

Zepper Brothers, they were pretty good. Had an elephant.

Funny old thing. Loved boiled eggs for some damn reason.

Speaker 8 Afforded to beat the band.

Speaker 8 Didn't mind the Carnival Obscura outfit neither.

Speaker 8

Fortune teller there was a Lulu. Told my fortune once when I had an extra four bits in my pocket.

That profile of Lady Liberty leapt from my palm to hers.

Speaker 8 She told me that I'd live an interesting life full of danger.

Speaker 8 Well, I laughed and laughed and says to her, I says, you old fraud, I was already born no bigger than a tater bug and worked the freak circuit for the past 20 years, and my eye was out before I ever met you.

Speaker 8 You ain't reading my fortune. You're just describing me.

Speaker 8 She laughed too. Truth is, she said, I'm mostly a fake, so you can have your four bits back.

Speaker 8 When I was leaving her trailer, my blood froze up something awful, though. She mentioned in an offhanded way how she sometimes got twinges, and one of them was of my somehow being a daddy.

Speaker 8 Though Though she knew I was a lifelong bachelor and bon vivant, a daddy of all things.

Speaker 8 When I closed the door, I left a 50-cent piece on her step.

Speaker 3 May I ask?

Speaker 4 The man gestured dismissively.

Speaker 8 Later, later.

Speaker 4 Then, instead, what would you say was the worst?

Speaker 4 His eyes darkened immediately, and he spat again, this time like an old gypsy cursing something too evil to mention.

Speaker 4 Before he could answer, the bearded lady was back, squeezing her bulk into an armchair set up at the head of the picnic table, shaded by a paper parasol wired to an old standing lamp.

Speaker 4 She set down three plates of breakfast, scrambled eggs, bacon, toast, and a carafe of coffee. Her nail varnish was perfect.

Speaker 4 The little man poured a cup of joe for each of us, moved his eggs around for a few moments. The scowl he'd adopted when I asked him his worst experience, deepening with each rotation of his food.

Speaker 3 I can't.

Speaker 4 He pushed away the plate.

Speaker 8 Margie, me and this fella are gonna take a walk. You uh keep yourself busy while we're gone.

Speaker 4 She leaned forward and kissed him on the cheek, patting a carry-all of knitting she had. She held up something that looked like a birdcage cover.

Speaker 7 For the baby,

Speaker 8 oh, that's well.

Speaker 4 The little man nodded, shuddered.

Speaker 3 Baby, I thought.

Speaker 4 He poured some bourbon from a pocket flask into each of our cups and got up from the table.

Speaker 8 Follow me me if you care to hear.

Speaker 4 He grabbed his cup and glugged half of it in one go.

Speaker 4 My coffee now tasted like kerosene, but I choked some down too.

Speaker 8 Homebrew.

Speaker 3 A paint thinner?

Speaker 8 Silver polish.

Speaker 8 Come on.

Speaker 4 We left the caravan behind and strolled along the marshy edges of the beach they were parked along.

Speaker 4 The wet earth sucked gently on our shoes.

Speaker 4 Why'd we have to meet in that bar last night?

Speaker 8 Why'd I have to play so badly?

Speaker 4 I shrugged.

Speaker 8 Ah, hell, it's probably good that I get this off my chest.

Speaker 8

The worst outfit I've ever known in this business. Well, that's easy.

Even though it was 50 years or more more ago when I was but a pup of 22.

Speaker 8 It was ran by the fellow I lost my eye over.

Speaker 3 A fellow I'm probably going to hell for.

Speaker 3 Professor Branson Boudreaux.

Speaker 4 He continued while I simply listened.

Speaker 8 Most men's principles can be had had incredibly cheap. Or at least that was what I learned when I was with Professor Branson Boudreaux's traveling show.

Speaker 8 I've been with Boudreaux since I was 14, back when he'd been known as Colonel Archibald Wanamaker.

Speaker 8 I, quite literally, had run away from home to join the circus, though said circus turned out to be a dipshit rip-off of Buffalo Bill's show with all the failure that endeavor implies.

Speaker 8 I knew he'd originally have been christened Elmer Harlow when he'd slithered out of his mama, but I hadn't been with him then.

Speaker 8 He'd learned in his time that a man had to spend money to make money, but his more valuable lesson had been in discovering that the amount of it that it took to grease most men's levers was next to nothing at all.

Speaker 8 A soul could be bought for pennies on the dollar.

Speaker 8 That was how he'd found himself first on the jury for Lonnie Fincher's trial for the murder of some deputy.

Speaker 8 Nobody had actually seen him do, after the mildest of contribution to hanging Judge Hacker's re-election fund.

Speaker 8 How he'd secured that guilty verdict amongst a few of the more reticent rubes in the farm trade with promises of a round on the house at the local saloon and tickets to a show he'd be too long out of town to ever provide.

Speaker 8 Lastly, it was on how he'd gotten an undertaker with more oat at the Pharaoh table than the man had the spread for to agree to lop off the boy's gunslinger hands and drop them in the glass jar of whiskey to feature them as Boudreaux's newest centerpiece.

Speaker 8 Me alongside him all the while.

Speaker 8 Law said the lad had fallen in with a bad crowd, but what of it?

Speaker 8 He was allegedly a robber, if the wanted posters had been anything to go by, but that didn't much phase the folks gathered around for the hanging.

Speaker 8 Lon had never taken a man's wallet, only robbed high-interest banks and a payroll coach or two, and he'd put most of that money back into those who'd most needed it.

Speaker 8 Local word was Widow Talmadge had gotten her property loan paid off with a mysterious pile of greenbacks that appeared on her porch one one day, secured down with a half a broken brick.

Speaker 8 Pete Johnson had seen his boy get an expensive doctor and a fine new leg brace from a small bundle that had been tucked into his saddlebag.

Speaker 8 And all that was aside from how the whorehouses and saloons up and down the Rio Grande had all seen generous increases in their incomes whenever Lonnie Fincher and his Wranglers went riding through.

Speaker 8 So it was hard for the townsfolk of Cherryville to feel much in the way of joy at the prospect of the boy being hung by the neck until dead for his crimes.

Speaker 8 His mother was near the front of the crowd, being supported by a friend and worrying a leather pouch she wore around her neck in the same hand that kneaded her hanky.

Speaker 8 Nearby stood a few young women who had their own private reasons to be sad about the demise of Lonnie Fincher.

Speaker 8 The preacher recited the Lord's Prayer and was halfway through the 23rd Psalm when Lonnie kicked his boots.

Speaker 9 Ain't you done yet?

Speaker 3 I was just trying to.

Speaker 9 I know what you was trying to, Reverend, but prolonging it is just going to be a waste of these folks' time.

Speaker 9 And mine, too, for that matter.

Speaker 9 Heaven or hell, whatever awaits me at the end of this rope is not going to be put off just because you can recite half the Bible standing here.

Speaker 9 Besides, you'll go and find you've spoiled your sermon for this Sunday by giving these fine people too generous of a preview beforehand.

Speaker 8 A little laughter sprang up at his boldness. I couldn't help but join in.

Speaker 8 With that, Lonnie cleared his throat, turned his head, and spat.

Speaker 8 And the executioner spat on him before yanking the black bag down over his head.

Speaker 8 That killed the breeze of mirth.

Speaker 8 It earned the brood a reprimand from the sheriff.

Speaker 8 John Laud even gone so far to take out his own handkerchief and wipe the boy's cheek clean before replacing the bag again, trying to avoid Lonnie's gaze.

Speaker 8 The faces in the crowd that were sad far outweighed those who felt justice was being done.

Speaker 8 Lonnie was well-liked, and someone most of the townsfolk had known back when he was in his ditties.

Speaker 8 A creak of wood, a bang, and there Lonnie Fincher was, dangling for all the crowd to see.

Speaker 8 His mother was the first to scream.

Speaker 8 Lonnie hadn't broken his neck, but danced in the air, the rope far too long for a man of his size and weight.

Speaker 8 His legs bucked and jigged, and the crowd wailed at the spectacle.

Speaker 8 Partway through, the bag which had been placed on his head, but not under the rope, began to come off.

Speaker 8 People could see Lonnie's face, tongue purpling and bloating out of his mouth, a scum of pink foam dripping down his chin, his eyes veined and red and bugging out grotesquely as he tittered and thrashed.

Speaker 8 I ain't seen a bull trout buck as much as that boy chaked on that rope.

Speaker 8 Bloody foam spattered down, and his eyes was pinker than a sick money's as they popped out.

Speaker 8 One woman fainted, even as his mother screamed and screamed.

Speaker 8 Even Judge Hacker turned from his upstairs window across the street and pulled the shade down.

Speaker 8 The sheriff grabbed for the boy's crawfishing legs, suffered a kick, redoubled his efforts, and then dropped himself.

Speaker 8 The crowd heard a crunch, and then Lonnie Fincher finally died. His body seizing up, trembling slightly.

Speaker 8 And just swinging there as it should have done from the start if the drop had been clean.

Speaker 8 The sheriff sat under the gallows for a second, catching his breath before crawling out and dispersing everyone as best as he was able.

Speaker 3 Show's over.

Speaker 8 He was right.

Speaker 8 But it had been one hell of a show.

Speaker 8 As ugly a picture as anybody'd ever wished for.

Speaker 8 Professor Boudreaux shook his head.

Speaker 3 Hell's Bells. If I could recreate that every night, I would make a goddamn fortune.

Speaker 8 Certainly.

Speaker 8 I said, put off by his glee at the genuine disgust and horror we'd just witnessed.

Speaker 8 Certainly, boss.

Speaker 8 He looked down at me.

Speaker 3 Oh, who gives a shit?

Speaker 8 He pushed past a lady, gasping behind him.

Speaker 3 Here I am talking to a sawed-off little bastard who goes to the whorehouse just for a free sniff about his views on entertainment.

Speaker 3 I must be out of my goddamned mind.

Speaker 8 That was the extent of the professor's friendship.

Speaker 8 When he wanted something, he could be purest honey. But when he didn't,

Speaker 8 the venom flowed even faster and goddamn you either way.

Speaker 8 Boudreaux was the kind of mean that's hard to put to words. He was so cynical, his views on life could curdle rancid milk.

Speaker 8 If you'd ever asked him about Cain and Abel, he'd say Cain's real problem was that he'd stopped after his brother.

Speaker 8

The crowd parted for Boudreaux as he strode along. Me scrambling to keep up, dodging horse apples and mud wallows all the way.

My world a constant curtain parting of coattails and skirts.

Speaker 8 Maybe that's why I took to the stage.

Speaker 8 I was so used to stepping out into the limelight as part of my daily existence.

Speaker 8 We passed the boy's mother, I still red-rimmed and spilling tears, weeping into her handkerchief. She clutched the small leather bag in her fist.

Speaker 3 We shall get you to the church, my dear.

Speaker 8 Her friend patted the grieving woman's shoulder as she got at her.

Speaker 3 This

Speaker 3 will provide better than that.

Speaker 8 She shook the bag

Speaker 3 The traveling medicine man told me this would not only offer me protection

Speaker 3 But revenge itself upon my enemies

Speaker 3 I don't know who got long to kill

Speaker 3 But it's worth no law

Speaker 3 if you say so

Speaker 3 Boudreaux went on never breaking stride

Speaker 3 Goddamn the morons. No wonder you can shear them blind.

Speaker 8 We reached the saloon and went in.

Speaker 8 The professor set himself to a card game and proceeded to best the table while the clock went round and round.

Speaker 8

How he never got shot, I'll never know. But he must have had the devil's own luck.

For a time at least, along with what had to be a half deck of aces and kings tucked into his sleeves.

Speaker 8 Cherryville rolled up its sidewalks around five or so and came alive again shortly after.

Speaker 8 Dry goods stopped, wet goods, in the form of baths and whores, started up.

Speaker 8 As evening drifted across the town, we ambled our way toward the funeral parlor, where Lonnie's body now lay, ready for the parting out for Boudreaux's wishes.

Speaker 8 The boy's corpse would end up with a pair of cowhide gloves stuffed with carrots, straw, whatever the undertaker saw fit to use in the place of Fincher's own flesh and bone at any rate.

Speaker 8 And there'd be no one the wiser when it was all said and done.

Speaker 8 Only someone richer.

Speaker 8 And that someone was Boudreaux.

Speaker 8 As he saw it, folks would come from far and wide just to see the genuine article. No fooling, powder-burnt hands of a cold-blooded murderer afloat in high-proof brine.

Speaker 8 Then they'd drag their moron friends back with them and pay two more bits just to gawck at those severed appendages all over again.

Speaker 8 Throw in an old pistol he'd bought to pawn off as the tool of the trade of said killer's hands, with me having notched the grip a dozen or so times to fit the patter he was cooking up about the numbers those hands had accrued, and the roofs might even pay four bits at a time when that was half a man's wages for a day.

Speaker 8 Boudreau's show had bits of your typical sideshow.

Speaker 8 A dog-faced gal named Irma, old 98-pounds and Joe, our six-foot-three human shadow, a couple of self-made freaks, You know, the type, a tattooed guy that looked just like a damn road map called Grady, and a fella that hammered nails into his face and bit the heads off chickens.

Speaker 8 Blockhead and a geek, all in one.

Speaker 8 Thomas

Speaker 8 always had a hunk of something shiny poking out of his nose. And me, I guess.

Speaker 3 The dwarf.

Speaker 8 We weren't what the people really came to see, though. What folks came for was Boudreaux's Grizzly Museum.

Speaker 8 The type of thing showmen like Barnum or this new fella, the one that does the comic strips, Ripley, have perfected.

Speaker 8 Ours was the raw version, a little less suitable for a family atmosphere, barring, of course, that we didn't have a Hoochie-Coochie show, though, not for Boudreau's lack of trying.

Speaker 8 Displayed amongst the shriveled apples, carved to look like genuine South American shrunken heads, and a collection of bottled snakes and mounted spiders, were the bones of Chief Runnin' Wolf, danded up in a buckskin outfit that Boudreaux claimed was a former companion of Sittin' Bull, who had died after taking down 20 cavalrymen himself at the Little Bighorn, armed with nothing more than one of them little hatchets the engines use.

Speaker 8 In reality, it was some two-bit medical skeleton he'd bought from a country doctor for six pints of whiskey.

Speaker 8 Then there came the head of Watro Tejas, and this one was honest, more or less. Floating in its jar of brandy wine, it was a Nickelodeon version of that old scoundrel, Joaquin Murieta.

Speaker 8 Tejas was the terror of almost no place at all. A trouser stain of a robber who'd failed almost every time until an angry Federale got fed up with him one day and out came his saber.

Speaker 3 Boudreaux happened to be around.

Speaker 8 A few greasy dollars changed hands and bango, Wancho Tejas, the terror of the West, joined the show, even if it was just the above-the-neck part.

Speaker 8 The last bit of pickled humanity was the one that always gave me the willies.

Speaker 8 It was a Siamese twin infant. Two heads split on a neck like a Y.

Speaker 8 One with a hair lip that made it look even more tragic.

Speaker 8 I dreaded every time I had to dust the show wagon and had to be near that thing.

Speaker 8 It's the idea of a child, and one in such a monstrous shape, made twice pitiable, once for Miss Carrion and once for knowing he'd have never lived even if he'd been born.

Speaker 8 I never asked how Boudreaux acquired the punk.

Speaker 8 There are some things I knew better than to ask.

Speaker 8 We stood side by side there in the dim, flickering light at the back of the mortuary parlor, among the hexagonal pine boxes, short at the top, long down the sides, and me with the shivers all the while.

Speaker 8 Loudreau rubbed his own hands together and waited.

Speaker 8 Sawdust coated the otherwise bare boards, and along one wall was a collection of saws and knives, rusty dull in the glare of the oil lamps.

Speaker 8 As much as folks complain about today, I guess nobody's ever really taken pride in their work.

Speaker 8 The undertaker came in presently, a cigarillo burning in his clenched teeth, and he made his way over to the board table where Lonnie Fincher was laid out after that morning's spectacle.

Speaker 8 Everybody had been there for the hanging, and the chatter about it would last for weeks.

Speaker 8 Partly, we knew, because in dusty little coach towns like Cherryville, new gossip would be chewed until the marrow was slurped from the bones, but also on account of how ugly it had been.

Speaker 8 As the fellow laid out Lonnie's body, we could see the horror up close.

Speaker 8 That tongue still bloated out like a salami, the eyes still bulged hens' eggs, and with them a pair of fresh hells.

Speaker 8 The raw burn where the rope had sawed into his throat as he bucked and twisted, and the gorder that had sprung up when the sheriff had broken his neck.

Speaker 8 The Undertaker recoiled.

Speaker 3 Damn shame.

Speaker 3 Boy was well lacked Would you get a hustle on?

Speaker 3 I was just saying I do not give a damn get to it

Speaker 8 I Stood to the side holding a large jar ready for the terrible prizes

Speaker 8 Up went the cleaver

Speaker 8 Down went the cleaver

Speaker 8 then came the cursing

Speaker 3 Son of a bitch

Speaker 8 The Undertaker nearly nearly bit his cigarillo in two.

Speaker 8 He braced the table with his foot and wrenched the cleaver out.

Speaker 8 As he rocked back and forth, the left hand of Lonnie Fincher came loose.

Speaker 8 He scraped it off the side of the table and I caught it in the jar with a meaty clunk.

Speaker 3 Hurry your ass up. I am.

Speaker 3 Damn it.

Speaker 8 The Undertaker gestured with the meat cleaver.

Speaker 3 This ain't easy work, mister. But if you're unhappy, by all means, roll up your sleeves.

Speaker 8 Boudreaux just crumbled. I smiled to myself at that, although I didn't know how bad things would get.

Speaker 8 And soon.

Speaker 8 We heard a commotion in the front of the Undertaker's shop.

Speaker 8 The parlor where he had his samples and frilly things set up to entice the locals into spending more than they could to bury their loved ones in style.

Speaker 8 Boots could be heard heading toward the back where we all stood before the Undertaker could even think of shifting his freight to head them off.

Speaker 3 What in the blue peat is going on in here?

Speaker 8 Behind the sheriff entered Lonnie Fincher's mother and her friend we'd seen earlier.

Speaker 3 These two fellas, they just came to pay their respects.

Speaker 8 It might have been a good answer, were he not holding a meat cleaver in one hand, dully gleaming where it wasn't streaked with blood, and there wasn't a showman and a dwarf would have one of the lad's severed hands in a jar standing there like our peckers was hanging out.

Speaker 8 Well, maybe not Boudreaux.

Speaker 8 That man never showed shame in his life.

Speaker 8 Boudreaux shot forward lightning quick and snatched the cleaver from the Undertaker, bringing it down through the boy's other wrist and tossing the hand to me.

Speaker 8 I caught the clammy thing and dropped it in the jar with its opposite, wiping my own up and down against my pants leg to relieve the feeling of Lonnie's dead flesh.

Speaker 8 That one

Speaker 8 Lannie's mother pointed at the boss. She snatched the leather thong from around her neck.

Speaker 3 You're the one done, got my boy killed.

Speaker 3 Now, Loretta May. Shut up! This man bribed the court and you knowed it!

Speaker 3 And for what?

Speaker 3 For my boy's hands,

Speaker 3 so he could add up to that threadbare flea circuit liz.

Speaker 3 Well, I'll be goddamned!

Speaker 8 She flung her leather bag at Boudreaux, and it hit him square in the chest.

Speaker 3 What is this shit?

Speaker 8 He emptied it into his palm.

Speaker 3 Oh, some feathers, a tooth, a chicken foot, and a dried something or other.

Speaker 3 Trash.

Speaker 8 He dropped them to the floor and grounded all into the sawdust with his boot, taking up the cleaver again.

Speaker 8 As he strode past the sheriff, me following along, the sheriff tried to grab his wrist, and he turned and buried the cleaver in the man's shoulder.

Speaker 8 The women started shrieking, joined by the tenor, banshee wail of the undertaker.

Speaker 8 I stared as a suspender strap slithered down the sheriff's shirt to hang there, even as the cleaver jutted from the now spouting wound.

Speaker 8 Boudreaux yanked my collar, and I followed him out onto the back of his waiting horse and out of Cherryville.

Speaker 3 That's the last time we can set foot in this

Speaker 3 hole.

Speaker 8 After that, it seemed like we was cursed.

Speaker 8 Everywhere we went, either nobody came to the show or Boudreaux found the local law's palms couldn't be greased.

Speaker 3 Or both.

Speaker 8 At the border of one town, we found a lynching party was there to greet us and to let us know neither we nor our coin was welcome in town.

Speaker 8 We said a lot for those days when even the money of recently freed men spent the same out of water and hole. We couldn't explain it.

Speaker 8 Communities were often wary of carney folk, sure, still are, but they were never this manner outright hostile.

Speaker 8 It was getting where we were having trouble getting enough feed for the horses pulling our wagons.

Speaker 8 We plodded our miserable carcasses up and down Texas, our outfit getting more and more fed up with each failed stop.

Speaker 8 I couldn't blame them. We was all mighty tired of beans and cornbread for supper, and not just for the horrendous toots we cracked day in and day out.

Speaker 3 A mutinous crew ain't ever a boon.

Speaker 8 A mutinous crew of angry freaks and wannabes worse.

Speaker 8 And to top it all, I was getting mighty tired of dusting that damn display wagon.

Speaker 8 The air felt closer inside than ever, and more than once I'd shocked myself reaching out to clean off some knick-knack in the back.

Speaker 8 Worst of all, those damned hands floated there like they'd signed our very own death warrants.

Speaker 8 We were on the verge of total collapse when Boudreaux took up a bottle one night and forced me to join in.

Speaker 8 Dragging me away from the fire where the rest of the crew was gathered, themselves passed out in whiskey slumber already.

Speaker 8 We walked to the back of the oddities wagon and sat on the steps leading up to it.

Speaker 8 He seemed like he'd had a snort already.

Speaker 3 We're ruined.

Speaker 8 He tilted the bottle back.

Speaker 8 I watched a fourth of it head down his throat in three huge swallows. I'd never heard Boudreaux express anything with such a fatleness.

Speaker 8 We'll scratch something up,

Speaker 8 I said, before tipping the bottle myself.

Speaker 8 I didn't really mean what I said.

Speaker 8 I didn't see how we could.

Speaker 3 I had such a pitch lined up, too.

Speaker 8 He pushed himself upright and staggered a few feet away.

Speaker 3 Ladies and gentlemen.

Speaker 8 And here he belched, though I doubt it would have been a regular part of the show.

Speaker 3 Ladies and gentlemen, you have here before you the hands of

Speaker 8 another belch, followed by a bump from the wagon behind me.

Speaker 8 A

Speaker 3 killer.

Speaker 3 That's right. Lonnie Fincher, who robbed banks and citizens alike up and down the Rio Grande, and even raised no little hell in New Mexico with this here pistol.

Speaker 8 He pulled out the pistol I'd notched and began waving it to and fro.

Speaker 8 I ducked, not wanting to get shot.

Speaker 3 And these here hands you see before you, that's right, folks. These are the genuine hands of a kid.

Speaker 8 A clattering thump shook the trailer behind me, and I hopped off the steps, staggering away.

Speaker 8 The door to the wagon burst open, and a body stepped out.

Speaker 8 The body, I call it that because there wasn't no other word for what it was, even though that's also not real close, was made of all Boudreaux's vile collection.

Speaker 8 The chief's dusty bones provided the frame.

Speaker 8 The severed head of Huancho Tejas, hair and mustache still sopping with brandy, eyes gone milky white, skin shriveled, snapping and gnashing its teeth led the way on top.

Speaker 8 Lonnie Fincher's hands sprouted from the wrists, grasping and closing on nothing as the thing tottered forward.

Speaker 8 I swung my head and spewed out my supper in a tobacco juice gush that steamed in the cold desert night.

Speaker 8 Wiping my mouth as I continued backing off, my lantern illuminated the thing as it lurched again. The chief's deerskin blouse flapping open to reveal the diabolical heart of the whole mess.

Speaker 8 It was the goddamn two-headed infant still floating in the jar, jammed up inside the ribcage and crying, gurgling, wet cries that it might have made when all the juice it should have known had been in its mama's teats instead of sloshing in its eternal pickle brine bath.

Speaker 8 I think that was the thing that first made me scream.

Speaker 8 All of it was terrible, awful, but that damned punk staring at me with four roving moon-blind eyes was the tipping point.

Speaker 8 The creature, revenant, undead, take your pick, swung one of those grasping starfish pale mitts at me and caught me up, boosting me free of the ground.

Speaker 8 And lordy, how monstrous strong that damn thing was. Every god-awful foot and inch of it, lurching like a sailor fresh off the boat.

Speaker 8 I hollered, yelled my fool head off, even as it kept going.

Speaker 8 Boudreaux stumbled along as best as he was able, turning every now and then to aim a shot at the thing.

Speaker 8 Though I don't know what he intended on hitting, since it was mostly bones and rags, and I was the only viable target in his line of sight.

Speaker 3 Crachow!

Speaker 8

The first shot whizzed past me and straight on through the ribs of the thing. Not even chip and bone.

Watch out!

Speaker 8 I said, turning to look at him as I was carried along.

Speaker 3 Watch out your own goddamn self.

Speaker 8 He cocked a hammer for another bite at the apple.

Speaker 3 Kerchow, Kerchow!

Speaker 8 The shot zipped past. One so close it left me with this groove in my earlobe, you see here.

Speaker 8 The other caught the head of Huacho Tejas right in the eye.

Speaker 8 And And damned if it didn't spin that two-bit pepperguts clean around in a confetti of pink gristle and chunks of jaw wider than a saucer plate and knocked his head free of that ghastly concoction of vinegar and bone.

Speaker 8 And damned if Lonnie's free hand didn't spring out and catch that head by the hair like a damned juggler and jam it right back on the neck with a squelch.

Speaker 8 Even as the right half of Tejas's face, most of the ear still present, flapped up and down like a seesaw in a high wind.

Speaker 8 The thing continued its march toward Boudreaux, flinging me away.

Speaker 8 I spun through the air like a Catherine wheel and landed face first in the dirt, my left eye spanging hard on a rock.

Speaker 8 Old Wancho's head and my own were now a mirrored pair in terms of missing parts.

Speaker 8 I pushed myself upright, not knowing exactly what had happened on account of how the eye itself don't really have a lot of nerves, or so the docs told me.

Speaker 8 And also because I was in shock from a hell of a lot of things that night.

Speaker 8 But I still watched as Boudreaux emptied the other three chambers on that gun he'd wanted to try to pass off as Lonnie's.

Speaker 8 Each shot blew nothing but hot air through that buckskin blouse.

Speaker 8 Then he tried to reload that pistol, spilling his pills in a jingling puddle of brass at his feet.

Speaker 3 Getting one in, then trying to spin the chamber, dropping more, getting another one.

Speaker 8 But as this pathetic attempt went on, the lane-handed thing closed distance on him.

Speaker 8 He looked up, flinging the gun at its chest, where it smacked to no effect and flumped into the dirt.

Speaker 8 He turned to flee as it got closer and caught his boot on a rock, going down.

Speaker 8 He then tried getting up again, half crawling, half limping on his newly twisted ankle. Neither good for trying to escape something from out of the pits of hell.

Speaker 8 Those hands closed and opened for Boudreaux now, and he knew it.

Speaker 3 No, you sons of bitches.

Speaker 8 He stumbled ran a few more steps, and then was caught up.

Speaker 3 Let me go.

Speaker 3 And that was it.

Speaker 8 For a man seemingly made to spite and patter, there wasn't much of either in his final pronouncement.

Speaker 8 The thing spun him round, and those hands closed on his neck.

Speaker 8 Wancho Tejas's broken smile grinned down at him, whispers of horse laughter issuing like a bellows sucked in through the ragged neck stump and out of that shattered, fluttering mouth.

Speaker 8 Lonnie's hands closed around Boudreaux's throat, tightening.

Speaker 8 The tendons on the back standing out as they squeezed and crushed and mangled.

Speaker 8 Boudreaux beat at them, pulling, and I watched the tendons holding them to the bones of the chief's wrists give way, wiry strands of gristle stretching before snapping under Boudreau's collapsing weight.

Speaker 8 And still the hands clung. Still they dug in as if they was trying to knead dough made of Boudreaux's neck.

Speaker 8 Boudreau's gasping noises had long since ceased, and now there was only a creaking, cracking noise as his eyes bugged out and his tongue purpled, and a pink foam curdled out of his mouth, just like Lonnie had gone through at his botched misery of a hanging.

Speaker 8 Dirt gritted under him as those hands closed around his neck, his own hands trying and failing to rest them free, themselves now opening and closing on little handfuls of meaningless soil, his feet digging smaller and smaller furrows as his strength faded.

Speaker 8 A final crunch and a spasm saw his end.

Speaker 8 And with it, Lonnie's hands let go.

Speaker 8 The chief skeleton took a juddering step forward, pitched to its knees, and collapsed, nothing holding the bones but whatever wire strung them together.

Speaker 8 Wancho Tejas' head rolled off and into the desert, whatever had animated it gone with the force behind the rest.

Speaker 8 I crawled over to Boudreau's corpse, half expecting the old devil to reanimate his own self. But he didn't.

Speaker 8 He just lay there, dead and pathetic. I saw it even wet his trousers as he'd gone.

Speaker 8 An odd frog splashing noise made me turn back to the remains of the thing that had flung me across the desert only a moment before.

Speaker 8 Those parts were scattered almost everywhere. Inside the rib cage was the jar containing that two-headed punk.

Speaker 8 I pulled the buckskin shirt apart and saw it still flopping around in the liquid.

Speaker 3 I don't know why.

Speaker 8 What made it different?

Speaker 8 Maybe because it had started out as a baby and never got to live the same amount of life the other bits had gotten.

Speaker 3 I don't know.

Speaker 8

Not even why they'd come alive. Was it Mrs.

Fincher's curse? Years of wickedness?

Speaker 3 All of it or none of it?

Speaker 8 I only know I picked up that jar, tucked it under my arm, and made my way back to the exhibit wagon.

Speaker 8 I collapsed into unconsciousness trying to get up the stairs.

Speaker 8 When I awoke a day later, head bandaged, everyone asked me what had happened.

Speaker 8 Everyone, included the local sheriff. I told him someone had robbed us, tacking me and then Boudreaux.

Speaker 8 The sheriff made mention of wondering where the thieves had got to, being there weren't no hoof prints or a load of boot heels leading the way.

Speaker 8 But seeing as how there weren't a better explanation, he ultimately accepted it.

Speaker 8 Boudreaux got a perfunctory funeral, wrapped in an old army blanket and rolled into a shallow pit.

Speaker 8 The show collapsed soon after and I moved on. That jar tucked into the bottom of my trunk with each outfit I joined.

Speaker 3 Why I kept it, I don't know.

Speaker 8 I mostly just drank and watched it jerk around in its soup as the nights wore on.

Speaker 8 But that's about it.

Speaker 8 That's the story of the worst show and man I ever worked for.

Speaker 8 Professor Branson Boudreaux.

Speaker 8 Wherever he is,

Speaker 3 I hope it's goddamn hot.

Speaker 4

I sat back as the little man finished speaking. Of course, I couldn't publish much of anything he'd told me.

It was foolishness.

Speaker 4 The years certainly take their toll.

Speaker 4 He flicked the saliva-slick butt of his cigar into a pile of seashells.

Speaker 4 A hermit crab prodded it a couple of times before scuttling off to find better pickings.

Speaker 4 The little man got up, dusting his knees, and began walking back toward the encampment.

Speaker 4 I followed along.

Speaker 8 Sorry I couldn't give you more, young buck, but it is what it is.

Speaker 8 Sometimes the truth can't be believed.

Speaker 3 Truth?

Speaker 8 Every last lick of it. That's the type of thing you don't ever forget.

Speaker 8 Not if you lived a hundred lifetimes.

Speaker 4 I said nothing as we walked.

Speaker 4 I'd wasted my time.

Speaker 4 Beat the guy at cards, gotten the promise of his story, then received this fishtail big enough to spit out Jonah himself.

Speaker 4 His lady had cleared up the breakfast plates and was finishing her knitting when we arrived back at the encampment.

Speaker 4 I sat on the stoop of their trailer, emptying the sand out of my boots, clapping the heels together as a pair of pinheads wandered past.

Speaker 4 I'd just finished retying my shoes when the little man tapped me on the shoulder and motioned me inside.

Speaker 4 He had the woman's newly knit cover in his hand. The trailer was dim, old furnishings and photos everywhere, a sunken-in mattress on the far end.

Speaker 4 At the other was a shelf with a worn drape.

Speaker 4 The little man parted that moth-eaten velvet curtain with one gnarled hand and stood back.

Speaker 4 Inside, I saw a jar.

Speaker 4 And in that jar, Floated a two-headed baby, bereft of life, face gnarled gnarled in a grimace of simultaneous birth and death.

Speaker 4 The hair lip not aiding it in the beauty department.

Speaker 4 It swirled gently in the murky bourbon-brown amniotic fluid in its glass womb.

Speaker 4 And then it put a hand against that glass and yawned.

Speaker 4 The hair lips spreading wide with the effort.

Speaker 4 Bubbles floated toward the lid of the jar as it did so.

Speaker 4 I started, stepping back and catching myself as I nearly tripped over the little man who strode forward with the knitting in hand.

Speaker 8 Earlier, you asked me about my being a daddy, like the fortune teller told me.

Speaker 4 He glanced back at me.

Speaker 4 Well,

Speaker 4 now you know.

Speaker 8 How much the rest you believe is up to you.

Speaker 4 He held up the cover and began to pull it over the jar.

Speaker 3 Now, if you excuse me,

Speaker 8 the baby is cold.

Speaker 6 Lily is a proud partner of the iHeartRadio Music Festival for Lily's duets for type 2 diabetes campaign that celebrates patient stories of support. Share your story at mountjaro.com/slash duets.

Speaker 6 Mountjaro terzepatide is an injectable prescription medicine that is used along with diet and exercise to improve blood sugar, glucose in adults with type 2 diabetes mellitus.

Speaker 6 Maljaro is not for use in children. Don't take Maljaro if you're allergic to it or if you or someone in your family had medullary thyroid cancer or multiple endocrine neoplasia syndrome type 2.

Speaker 6 Stop and call your doctor right away if you have an allergic reaction, a lump or swelling in your neck, severe stomach pain, or vision changes.

Speaker 6 Serious side effects may include inflamed pancreas and gallbladder problems. Taking Maljaro with a sulfinyl norrhea or insulin may cause low blood sugar.

Speaker 6 Tell your doctor if you're nursing pregnant plan to be or taking birth control pills and before scheduled procedures with anesthesia.

Speaker 6 Side effects include nausea, diarrhea, and vomiting, which can cause dehydration and may cause kidney problems.

Speaker 6 Once weekly Mount Jaro is available by prescription only in 2.55, 7.5, 10, 12.5, and 15 milligram per 0.5 milliliter injection.

Speaker 6 Call 1-800-LILLIRX 800-545-5979 or visit mountjaro.lilly.com for the Mountjaro indication and safety summary with warnings. Talk to your doctor for more information about Mountjaro.

Speaker 6 Mount Jaro and its delivery device base are registered trademarks owned or licensed by Eli Lilly and Company, its subsidiaries or affiliates.

Speaker 3 In our final tale, we deal with war. War, as we know it, isn't limited to large conflicts like world wars.

Speaker 3 For years, countries around the globe have dealt with regional wars which are just as devastating to their populations.

Speaker 3

And in this tale, shared with us by author Daniel J. Green, we meet a man returning to his homeland to grieve his brother.

And this is a man whose past is soon to catch up with him.

Speaker 3 Performing this tale are Graham Rowett, Marie Westbrook, Erika Sanderson, Tanya Milosevic, and Jake Benson.

Speaker 3

So understand this. Citizens don't soon forget the horrors of war.

Especially not the Raven Man.

Speaker 3 In the back of the cab, I chew my lip to shreds and wait to present my passport.

Speaker 3 I haven't been back here in 30 years,

Speaker 3 but oddly, it still feels like home.

Speaker 3 They say there's no place like home, that home is where the heart is, all that shit.

Speaker 3 I have a much more complicated relationship with Bosnia and Herzegovina.

Speaker 3 For me, home has always been a place of dread and unimaginable suffering. A place where flaming steel rains from the sky at random.

Speaker 3 Or your friends and neighbors can turn to bleeding pulp at any moment.

Speaker 3 But it's still home.

Speaker 3 Home is important,

Speaker 3 but it's never simple.

Speaker 3 The border guard scans the empty pages of my passports, glances at me over his glasses and then stamps it with black ink.

Speaker 3 The driver hands the document back to me, and I exhale.

Speaker 3 I'm home

Speaker 3

for most of its history. Bosnia has inhabited a liminal state.

Half European, half Asian, half Christian, half Muslim,

Speaker 3 half alive, half dead.

Speaker 3 In the 90s, it was apt to compare the endless rows of cemetery crosses in the hills around every town to the teeth of an ever-growing beast.

Speaker 3 For nearly a decade, that beast fed on women, children, and hollow-eyed men, only growing in strength and size by the year.

Speaker 3 Today, the beast still lives, but its fangs have grown sallow and brittle.

Speaker 3 Its fat, green belly no longer swells with the blood of youth, but with that of the old, sick and jaded.

Speaker 10 Merkowski,

Speaker 3 the hostel receptionist eyes my passport.

Speaker 10 That's not a Serbian name.

Speaker 3 She's sucking a cigarette under the no-smoking sign in the lobby, as if the hypocrisy were intentional.

Speaker 3 No, it's not.

Speaker 10 So, how do you speak Serbian so well?

Speaker 3 I was born here.

Speaker 10 Of Polish parents?

Speaker 3 What do you care?

Speaker 3 She clicks her tongue and takes another drag off her cigarette.

Speaker 10 Your 214 laundry is four marks. There's a market down the street where you'll find everything you need.

Speaker 3 Like I said, I was born here.

Speaker 10 Then you will have no problems.

Speaker 3 She slides the room key across the counter and with that, it's as if I no longer exist.

Speaker 3 The floorboards groan under the weight of my step as I enter the room.

Speaker 3 For an extra extra five marks, I booked a queen bed, which now turns out to be two singles pushed together and draped with a sheet.

Speaker 3 The big luxury here is the private balcony. I pull open the sliding door and lean against the railing to peer down at the street below.

Speaker 3 Beyond the asphalt, I can see the woods, black and green, and as ominous as I remember.

Speaker 3 Even before the 90s, before they were littered with land land mines and booby traps, the locals would tell stories about the evils that lurk there.

Speaker 3 These woods have always exhibited an odd shifting quality, making them almost impossible to navigate. Just when you think you've found your bearings, you step out into an unrecognizable plain,

Speaker 3 or stranger yet,

Speaker 3 into a familiar street in the town itself.

Speaker 3 Attempting to memorize the woods, twisting valleys and rugged terrain is like trying to memorize the swirling patterns of the wind.

Speaker 3 This phenomenon is so commonplace to locals that it's rarely discussed. It merely looms in our collective subconscious, like the inherent danger of fire.

Speaker 3 Of course, this never kept children, myself included, from playing in the woods. In my younger days, I was considered one one of the few who could navigate them with success.

Speaker 3 This reputation followed me into the war, where my skills were put to tactical use.

Speaker 3 I know all the places where people wander, the force shortcuts, the trails where the trees seem to herd you into endless, infuriating loops.

Speaker 3 These are the places where the Bosnian soil drank most deeply the blood of traitors.

Speaker 3 I'm about to leave the room to head to the market when I find a letter on the floor by the door and immediately recognize my uncle's writing.

Speaker 3 The receptionist must have slipped it into my room and the time it took me to step out onto the balcony. I tear open the envelope and read:

Speaker 3 Peter Merthnitz.

Speaker 3

Sorry about your brother. My lawyer will meet you at the Golden Falcon Bar Thursday at noon.

He will finalize the sale of Darko's property and the funds will be transferred to your account.

Speaker 3 He is very good, so you do not need to worry. Then you can go back to your imperialist swine country.

Speaker 3 With love,

Speaker 3 Ivan Mertnits.

Speaker 3 I smile as I read the last lines. If Uncle Ivan weren't the last living Mertnitz in all of Bosnia and Herzegovina, I wouldn't waste a second with the old socialist bastard.

Speaker 3 Such complex processes as selling foreign property become a lot easier when you have a man on the inside, though.

Speaker 3 Since I left, Bosnia's system of government has devolved into a bureaucratic shit show.

Speaker 3 That's part of the reason few of my blood relatives remain here. They all left for greener pastures.

Speaker 3 USA, Australia, Switzerland, or in my case, Canada.

Speaker 3 However, I can't truly say I left for greener pastures. A better way to put it would be that my political differences forced me out.

Speaker 3 This new EU puppet state doesn't approve of my kind, nor my ideology.

Speaker 3 Thus, the new name,

Speaker 3 Murkowski.

Speaker 3 A Serbian name like Mersniets, aside from being nearly impossible for most English speakers to pronounce, raises far too many questions.

Speaker 3 A A nice Polish name is much easier in Canada, a land where every white person is a third immigrant of some confused European ancestry, where bloodlines mean nothing, and where a Polish accent and a Bosnian Serboan are, for all intents and purposes, indistinguishable.

Speaker 3 I fold the letter and tuck it away before continuing down the hallway and the stairwell. Before I can step out the front door, I hear the receptionist's voice ring out from behind the desk.

Speaker 10 See you later, Mr. Musnitz.

Speaker 3 I freeze.

Speaker 3 Before I can turn to speak, she disappears.

Speaker 3 Goddamned Snoop.

Speaker 3 The market is farther away than I remember. Once inside, I waste no time finding the brandy aisle.

Speaker 3 Here, even the cheapest Bosnian plum brandy is better than the bottles of Swill exported from Croatia.

Speaker 3

A few glasses of this should make up for lost time. I reach for a bottle, but stop as I sense someone staring at me.

When I turn, I see an ancient Bosnian woman, her eyes locked on mine.

Speaker 3 I try to ignore her as I choose my bottle and head for the register. But my efforts prove fruitless when I realize she's the cashier.

Speaker 3 She waddles behind the counter and holds out a plastic bag for my bottle.

Speaker 3 Don't need one.

Speaker 3 She croaks back in Bosnian.

Speaker 3 Whatever you say, Mr. Mersnitz.

Speaker 3 Hearing my family name in that dialect, in this part of the country, takes my breath away.

Speaker 3 When I look at her, I see my own confused terror registering in the black pits of her eyes, and she laughs.

Speaker 3 No,

Speaker 3 you didn't kill all of us.

Speaker 3 Let's give Dean Max for the brandy.

Speaker 3 But

Speaker 3 oh,

Speaker 3 thoughts, questions, nightmares were through my mind?

Speaker 3 It said ten marks on the sheriff.

Speaker 3 And how did you.

Speaker 3 Your money should be the least of your worries.

Speaker 3 Fifteen marks for the brandy.

Speaker 3 What?

Speaker 3 You're a crook?

Speaker 3 and you're a murderer.

Speaker 3 I open my mouth to speak, but nothing comes out.

Speaker 3 I place the 15 marks on the counter as I step away, watching her the whole time as if at any moment she might turn into a rabid beast and leap the counter.

Speaker 3 I'm about to cross the threshold when she begins shrieking at an unholy pitch.

Speaker 3 Nobody has forgotten!

Speaker 3 Nobody!

Speaker 3 I bolt out of the store, heart pounding in my ears. But in my panic, I trip and drop the bottle to the ground, where it explodes against the ashwork.

Speaker 3 In a reflexive attempt to break my fall, I put my hands forward, just in time to lodge the broken shards of glass into my palms. Red rivulets pour down my wrists as I writhe on the ground.

Speaker 3 Bloody and doused in brandy, my next thought is to turn and protect myself from the old woman, who I assume will be standing over me, ready to bash my skull in.

Speaker 3 But when I look, I see that it's just me, alone,

Speaker 3 panting in my own filth.

Speaker 3 That is until a young girl in a red store apron bursts through the door and gasps upon seeing me.

Speaker 3 My God!

Speaker 3 She hurries to me, unties her apron, and presses it to my leaking hands.

Speaker 3 I knew you should have taken a bag for that.

Speaker 3 She clicks her tongue as I pull away the apron to look at the carnage.

Speaker 3 She gasps again as I extract a shard of glass from its scarlet socket.

Speaker 3 You need a doctor.

Speaker 3 Never mind.

Speaker 3 I say, maybe a little too gruffly. I stand, keeping the pressure on my wounds while ignoring the growing static in my ears.

Speaker 7 Well, at least let me replace that.

Speaker 3 She disappears for a moment and returns with a new bottle.

Speaker 3 Here.

Speaker 3

I smile at her. So innocent.

So caring.

Speaker 3 Then, for the first time, I notice her Serbian accent.

Speaker 3 That couldn't have been your mother yelling at me, could it?

Speaker 3 Is the old woman always so miserable?

Speaker 3 She tilts her head, confused. An uncomfortable silence grows between us.

Speaker 3 You must have heard the commotion.

Speaker 3 I'm sorry if I said something to offend her, but my god, the way she was screaming.

Speaker 3 again, she looks at me silently, like I'm speaking a foreign language.

Speaker 3 Maybe get home and rest, sir.

Speaker 3 You sure you're all right?

Speaker 3 I wait for her to say something, anything that makes sense, but it doesn't come.

Speaker 7 I need to watch the register now,

Speaker 3 and then she's gone.

Speaker 3 Back in my room, I tear the sleeves from an old shirt and wrap my palms. When I'm finished, the bathroom reeks of blood and plum liquor.

Speaker 3 The static in my ears has grown to a steady din after a few shots of brandy. And the last thing I need is to faint and bust my teeth on the floor, so I stumble to the bed and collapse.

Speaker 3 I paw at the remote control and, after a bit of fumbling, managed to switch on the television.

Speaker 3 The news shows demonstrations in the Bosnian Serb capital Bonjoluka, where young men brandish signs and guns.

Speaker 3 I switched to a singing show where a beautiful Macedonian girl belts out a melody about her homeland.

Speaker 3 I'm about to switch to the next channel when a commotion on the balcony diverts my attention.

Speaker 3 I look, but at first can't make out what I'm seeing or hearing, being that I'm drunk on brandy and blood loss.

Speaker 3 But when I squint, I can see black, undulating shapes just through the space where the drapes almost meet.

Speaker 3 Then that sound again-a clicking, dragging sound, like a dog with long toenails scampering across hardwood.

Speaker 3 But there's another sound accompanying it too. A cavernous croaking, singular at first before growing into a chorus.

Speaker 3 Despite my dizziness, I leap from bed to see what the hell is going on. When I tear the drapes apart and slide open the door,

Speaker 3

I see ravens. At least a dozen of them.

Perched on the railing of my balcony and along the metal backs of the chairs. As one, they turn their glassy eyes on me and fall silent.

Speaker 3 Shoo!

Speaker 3 Shoo!

Speaker 3 I try to scare them away by waving my bloody hands, but they stand their ground.

Speaker 3 Alright then,

Speaker 3 I step back into my room and retrieve the broom from the closet.

Speaker 3 Come on now. Shoo!

Speaker 3 I swipe at them with the broom, but they dodge it by leaping to the air and beating their long saffin wings.

Speaker 3 The moment I stop, they simply land on the railing again and glare at me.

Speaker 3 You sons of bitches!

Speaker 3 I cock the broom back and prepare to deliver a fatal blow. But just then a high-pitched whistle, sharp as a scalpel to my eardrums, cuts the air.

Speaker 3 I stop and watch in awe as the ravens lift into the sky in unison before swooping down to the street.

Speaker 3 I didn't notice him at first, but I see now there's a man standing there. He lifts his arms to create makeshift purchase for the birds.

Speaker 3 Those that can't find space on his arms congregate at his feet like a shadow.

Speaker 3 Hey,

Speaker 3 your birds shit on my balcony.

Speaker 3 Silence

Speaker 3 dozens of dead obsidian eyes stare back at me

Speaker 3 If they come up here again, I'm going to kill them you understand

Speaker 3 I strain my eyes to read the features of his face, but it's too dark All I can see is the blank oval of his head atop narrow shoulders.

Speaker 3 He's tall, rail thin, wearing a black coat that falls to the pavement.

Speaker 3 You hear me, Raven Man?

Speaker 3 The asshole is ignoring me.

Speaker 3 He drops his arms and his shadow of birds transforms into a storm cloud that thrashes and screeches above his head.

Speaker 3 As he turns to the woods, I catch a glimpse of the sight of his face in the streetlight, and sour bile stings my throat.

Speaker 3 By the time I can process what I've seen, he and his ravens are gone.

Speaker 3 Am I losing my mind?

Speaker 3 How much blood have I lost?

Speaker 3 The man's face

Speaker 3 looked melted or burnt right down to the muscle. He had no nose, no cheeks, hardly any flesh at all.

Speaker 3 There's a pounding on my door, and my heart nearly stops.

Speaker 3 Christ what now

Speaker 3 When I open the door I see the receptionist with a cigarette in her mouth looking thoroughly unamused

Speaker 10 You haven't been here two hours and have already received complaints

Speaker 3 She glances at my hands but doesn't comment

Speaker 3 about

Speaker 3 what

Speaker 11 you were just yelling from the balcony, threatening Dragon that you would kill his birds.

Speaker 10 I heard it from downstairs.

Speaker 11 I didn't need the phone calls from the other guests to know that you were coming unraveled.

Speaker 10 I'm going to kick you out if you don't smarten up.

Speaker 3 Wait, Dragon

Speaker 10 Raven Man, as you called him.

Speaker 3 You know that freak?

Speaker 10 Of course.

Speaker 11 I thought you were born here.

Speaker 3 Well, his damburn's made a mess of my balcony. I hope you have fun cleaning that up.

Speaker 10

Mind your own business, Mr. Musnitz.

I mean, Merkowski.

Speaker 3 Oh, that's rich coming from you.

Speaker 3 Stay the hell away from me. And if you tamper with my mail again, I'll go to the police.

Speaker 3 Her cigarette smoke curls around her face as she glares at me she turns to leave but i have to ask

Speaker 3 what happened to him

Speaker 3 she stops but refuses to give me another look

Speaker 11 you of all people should understand what happened to dragon you and your paramilitary thugs

Speaker 3 she shakes her head and disappears down the hall.

Speaker 3 When I return to the market the next morning, I see the same young girl at the register.

Speaker 3 She gives me a quick double take, but otherwise ignores me as I saunter through the aisles and collect my ingredients.

Speaker 3 Flour, yeast, rat poison, more plum brandy, and everything else I can get from the communal kitchen at the hostel.

Speaker 3 There's terror in the girl's eyes as she rings up my items.

Speaker 3 And a pack of Dorinas, king-sized.

Speaker 3 She nods, reaching for the cigarettes.

Speaker 3 Anything else?

Speaker 3 No.

Speaker 3 I smile.

Speaker 3 This will do just fine.

Speaker 3 When the loaf of bread comes out of the oven, it looks ominously delicious.

Speaker 3 Crisp brown crust, worn, fluffy middle, intoxicating aroma.

Speaker 3 Those damned birds won't be able to resist.

Speaker 3 Back in my room, I tear it the crumbs and scatter it evenly across the balcony. Then, just for good measure, I throw some over the railing like a fisherman chumming at sea.

Speaker 3 My work complete, I wash my hands of the poison and plop onto my bed to watch the shore.

Speaker 3

The room fills with smoke as I burn through my cigarettes and drink my brandy. There's nowhere I'd rather be.

Nothing I'd rather be doing, I think to myself.

Speaker 3 Vengeance is in my blood. It's who I am.

Speaker 3 My eyelids grow heavy as I stare out the balcony window and wait for the ravens to return. I close my eyes and, for what seems like only a few minutes, I disappear into the oblivion of sleep.

Speaker 3 I awake with a start to the familiar clack of talons on metal.

Speaker 3 Looking out the window, I see black feathers bobbing and pecking at the floor of the balcony, the toxic crumbs having long disappeared down the birds' silken gullets.

Speaker 3 I jump from bed and fling the balcony door open, causing the birds to flee to the railing. An evil, guttural laugh builds momentum in my stomach as I realize their defeat.

Speaker 3 I merely double over when a familiar whistle cuts the afternoon air, and the birds flock to their gaunt and ragged master on the street below.

Speaker 3 Oh, hello there, Raven Man!

Speaker 3 I thought I would miss you today!

Speaker 3 Being closer to him now, in the light of day, I can better make out the scars on his face. It looks as though he's wearing a bad Halloween mask.

Speaker 3 All of his extremities appear to have been eaten away by fire. Ears, nose, chin, all gone.

Speaker 3 What skin remains droops like cheap plastic left to warp in the sun. Black gloves cover his hands, and a long black coat conceals everything else.

Speaker 3 I figured that after all their shooting last night, your little friends would need a snack.

Speaker 3 I start to laugh again.

Speaker 3 I can't help it.

Speaker 3 It's just so sweet.

Speaker 3 Are they full now, or do you suppose they need some more?

Speaker 3 Whether by choice or because his wounds prevent him from speaking, he says nothing and retreats into the woods, his loyal black storm cloud close behind.

Speaker 3 Farewell, my friends!

Speaker 3 Come back soon!

Speaker 3 I'm grinning ear to ear as I return to my room. It's not even noon yet, and I've accomplished so much.

Speaker 3 I snatch the brandy from the dresser and take a long, celebratory swig.

Speaker 3 The sweet, fiery liquid stings my belly as I drop to my bed in a fit of laughter.

Speaker 3 I imagine those damned birds dropping from the sky, twitching on the ground, contorting the various angles of death as their master kneels before them, himself broken inside and out.

Speaker 3 God, it's sweet

Speaker 3 after a few moments, though, the feeling passes,

Speaker 3 and I'm left empty.

Speaker 3 I hadn't planned on succeeding so quickly, and now my mind begins to spin.

Speaker 3 How will the Raven Man react?

Speaker 3 Will he confront me? Will he, in turn, seek revenge?

Speaker 3 Oh, how I would love to see him try.

Speaker 3 My face flushes with rage as I imagine it. In one motion, I rise from bed to grab the bottle, but as I tip it back, only a few warm drops of backwash drip onto my tongue.

Speaker 3 Son of a bitch.

Speaker 3 I squeeze the bottle, my knuckles stretching white as I consider chucking it across the room.

Speaker 3 Patience, Peter.

Speaker 3 I take a deep breath as I pace the room. I shake my head as if to clear the image of the Raven Man scorched onto my retinas.

Speaker 3 He's just a freak.

Speaker 3 What's he going to do? Sick his birds on me.

Speaker 3 I try to laugh again, but it feels forced now.

Speaker 3 Damn it, Peter. It's time to celebrate, not mope around.

Speaker 3 I find my shoes and begin tying the laces.

Speaker 3 I need a drink.

Speaker 3

The Golden Falcon Bar is one of the few establishments in this town that hasn't changed much since the war. Inside, they still display the Serbian cross.

They still serve Nectar Pivol.

Speaker 3 A Bosnian Serb beer that's hard to get in other parts of this country.

Speaker 3 And on the menu, they use the Serbian spelling for the word bread.

Speaker 3 They've even hung the Serbian flag on the wall, albeit right next to the Bosnian one.

Speaker 3 I smile as the bartender rounds the corner and takes my order for a beer.

Speaker 3 Anything else?

Speaker 3 Give me a plum brandy. It's homemade, right?

Speaker 3 He smiles, revealing two rows of jaundice teeth.

Speaker 3 Of course, brother.

Speaker 3 When he returns, he's carrying two glasses. One for me and one for himself, I presume.

Speaker 3 You speak our language like a local, but that's a unique accent you've got. You're from around here,

Speaker 3 of course.

Speaker 3 Republica Srpska, born and raised. The greatest country that never was.

Speaker 3 He laughs and looks around the empty bar before taking his seat across from me.

Speaker 3 Don't get me started.

Speaker 3 He lifts his glass.

Speaker 3 To Bosnia.

Speaker 3 And to Serbia.

Speaker 3

Something flashes across his eyes. A thought, a memory, a flicker of recognition.

But whatever it is, he keeps it to himself.

Speaker 3 She will

Speaker 3 down the brandy.

Speaker 3

It's homemade, all right. Fiery and undiluted.

As we finish, I catch him with that look in his eye again.

Speaker 3 I'm about to bring it up, but he speaks first.

Speaker 3 You look like you've been to war.

Speaker 3 The comment catches me off guard, but then I see him looking at the bandages on my hands.

Speaker 3 Yeah,

Speaker 3 in more ways than one.

Speaker 3 I chase the homebrew with a deep swallow of beer.

Speaker 3 Speaking of which,

Speaker 3 who is this freak I keep seeing? He's tall, dressed in black, horrible face, followed around by birds.

Speaker 3 He crosses his arms and smiles.

Speaker 3 Ah, yes.

Speaker 3 Dragon.

Speaker 3 So, who is he?

Speaker 3 An old sergeant of the Bosnian army. There's still a few of them around.

Speaker 3 And what happened to his

Speaker 3 I gesture vaguely to my upper body?

Speaker 3 They all know how things ended.

Speaker 3 The spark of his lighter casts deep shadows under the bags of his eyes as he lights a cigarette. He speaks as if he's saying the most obvious thing in the world.

Speaker 3 He and his men, they were fighting with what was left behind, finding a gun here, some ammo there.

Speaker 3 The Bosnians were a bunch of ragged, starving teenagers back then. They had all the men digging trenches so their grandchildren could go out with shotguns to fight the entire Serb army.

Speaker 3 It was pitiful.

Speaker 3 We all knew how it would end.

Speaker 3 Just not when.

Speaker 3 He takes another drag off his cigarette, and then I see it again.

Speaker 3 That implacable look of knowing, of remembrance, of a memory that no words can express.

Speaker 3 Well, one night it ended.

Speaker 3 The Serbs surrounded the farmhouse where he and his men had been hiding out from the shelling, laid down some heavy machine gun fire to keep them away from the doors and windows, and sealed the place up tight.

Speaker 3 You know,

Speaker 3 barricaded the doors, put it up the windows. Then they doused the place in gasoline.

Speaker 3 I'm waiting for him to continue when I see his hands are shaking.

Speaker 3 Somehow, Dragan lived.

Speaker 3 All those young men burnt up, and somehow, he lived.

Speaker 3 Of course,

Speaker 3 he was a mess.

Speaker 3 Reports got out that the Bosnian army had finally been defeated here, so a UN convoy came through to look for evidence of war crimes.

Speaker 3 The Serbs would have just executed the poor bastard on the spot.

Speaker 3 But they had to be on their best behavior.

Speaker 3 He was taken to a big military hospital in a safe area and nobody saw him again until the end of the war.

Speaker 3 Even after all that, he refused to leave this town.

Speaker 3 Never spoke again, though.

Speaker 3 Over the years, the locals have come to regard him as a sort of folk hero, as some kind of chosen one, protected by a higher power.

Speaker 3 Those ravens, you see? They say they are the souls of the boys who burnt up in the farmhouse.

Speaker 3 He snorts and rises to his feet.

Speaker 3 It's all magical western thinking.

Speaker 3 Those men are ash now.

Speaker 3 Dead.

Speaker 3 They've been absorbed by the Bosnian soil.

Speaker 3 Like so many of our brothers.

Speaker 3 He steps away from the table and returns with the whole bottle of homemade brandy.

Speaker 3 We drink another round before he shoots me that look again.

Speaker 3 I'm sure you have your fair share of stories. Where are you in all that hell?

Speaker 3 My head is spinning from the day's drinking, but I managed to keep from slurring my words too much.

Speaker 3 This war was over thirty years ago now,

Speaker 3 but as I look around, I realize that in many ways, it never ended.

Speaker 3 I used to call these woods my home, you know.

Speaker 3 I played in them as a boy, and then I hunted in them as a man.

Speaker 3 My motor crews trusted me to navigate these woods.

Speaker 3 My infantry would follow me because they trusted me to lead them around the mines, I'd said.

Speaker 3

Of course, as an engineer, laying mines was my bread and butter. I set them perfectly.

I was the best. I hid them between rocks, next to tree roots.

It was all a deception.

Speaker 3 I built paths to death, you see.

Speaker 3 I laughed and sucked down another gulp of beer.

Speaker 3 I'd hear the mines going off as I laid in my bunk at night. Sometimes the sound would be followed by moans or calls for help.

Speaker 3 Then another blast and another.

Speaker 3 In the morning, we'd go in there and clean up the pieces and collect the weapons

Speaker 3 as I speak I catch a twitch in the bartender's eye

Speaker 3 He's not smiling anymore, but I can't seem to stop talking

Speaker 3 Then there were the tripwires

Speaker 3 setting those was glasses empty brother

Speaker 3

Before I can check he's already collected it now. He's filling it at the bar.

He's teleported there somehow, it seems. The liquor must be really hitting my bloodstream.

My reaction time is delayed.

Speaker 3 Events around me seem to finish before I can comprehend that they've even begun.

Speaker 3

The next thing I know, I'm holding a fresh glass of beer. I'm bringing it to my lips.

And when I look down, I see that half the drink is gone, and my lips are wet and sweet.

Speaker 3 As I was saying, I wait.

Speaker 3 Don't tell me I'm talking to who I think I'm talking to.

Speaker 3 I try to look into his eyes, but somehow I can't seem to find them on his face.

Speaker 3 I was the

Speaker 3 best at setting tripwires.

Speaker 3 I try again.

Speaker 3 You're not.

Speaker 3 You're not Sergeant Muznich, are you?

Speaker 3 I swallow the rest of my beer and slam the glass on the table.

Speaker 3 You're damn right I am.

Speaker 3

I look up in time to see two men standing over me. Two unfamiliar faces.

Two impossibly unfamiliar faces.

Speaker 3 Where did they come from?

Speaker 3 They grabbed me under the arms and drag me to the front doors.

Speaker 3 Get your hands off me!

Speaker 3 You're drunk.

Speaker 3 I open my eyes in time to see black asphalt careening toward my face.

Speaker 3 I don't feel the impact as I hit the ground, but I taste the blood flowing into my mouth. The collision jars me back to lucidity, and with it comes a wave of fresh pain.

Speaker 3 I run my tongue over my front teeth and feel two jagged nubs of enamel. With legs of rubber, I manage to stumble back to the door from which I was just flung.

Speaker 3 You sons of

Speaker 3 your mothers are

Speaker 3 I don't have time to finish my curse before I notice the barrel of a shotgun pointed at my skull.

Speaker 3 Go home, Peter.

Speaker 3 The bartender grips the gun. All of his previous hospitality has dissolved.

Speaker 3 All the way home, wherever the hell that is he stays. You're not welcome here anymore.

Speaker 3 Oh, come on!

Speaker 3 I spit a mouthful of blood and tooth fragments onto the street.

Speaker 3 Don't tell me they got you too!

Speaker 3 Fuck me! You're all puppets of a European state!