S2 E4: The repo man of the seas

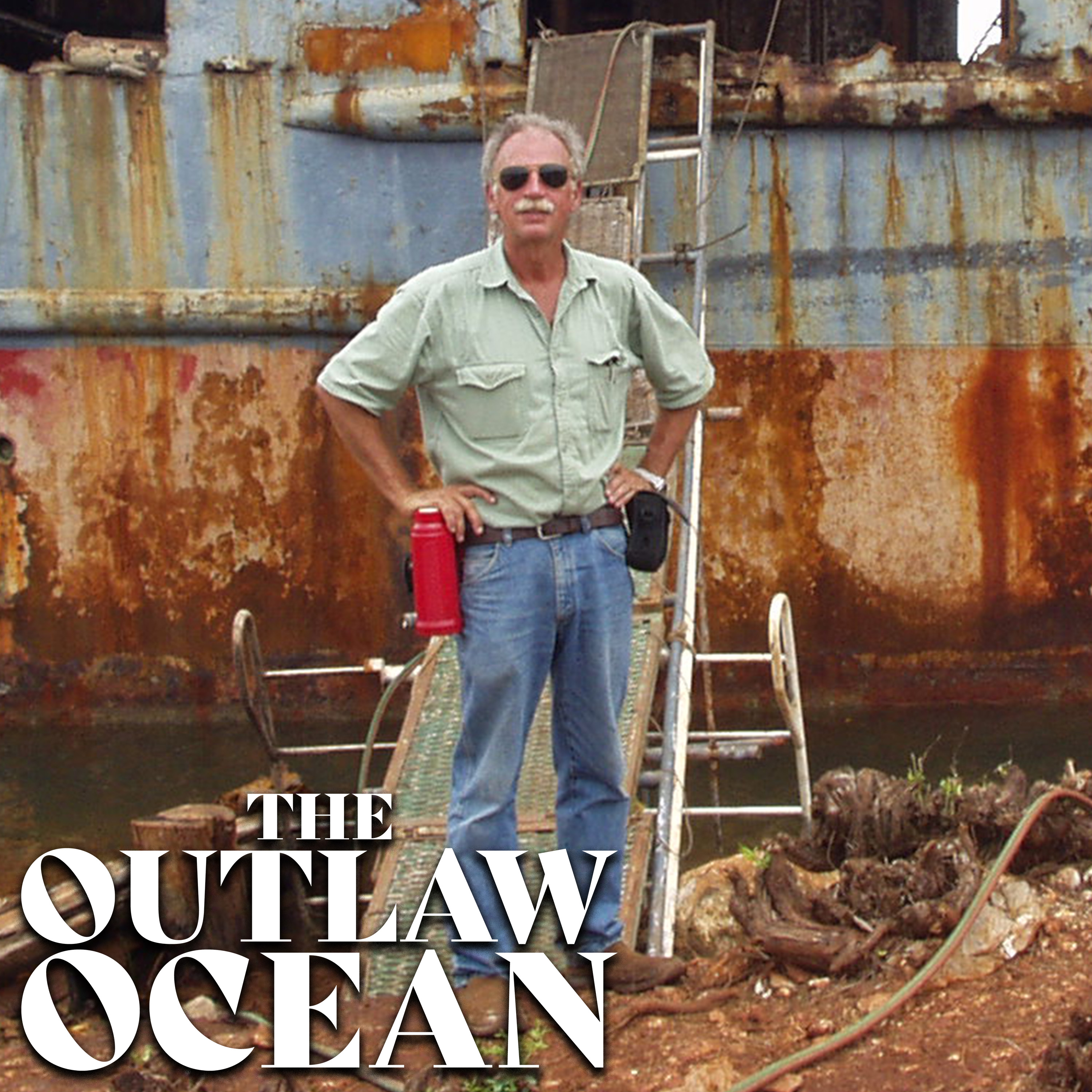

Depending on who you ask, Max Hardberger is either a seagoing James Bond or a swashbuckling pirate. Hardberger runs a rare kind of repo service, extracting huge ships from foreign ports. His company is a last resort for ship owners whose vessels have been seized, often by bad actors, and over the years he’s built a reputation for taking the kinds of jobs others turn down. Hardberger’s specialty is infiltrating hostile territory and taking control of ships in whatever way he can – usually through subterfuge and stealth. Whatever part of the world his missions take him, Hardberger thrives in its grey areas.

Episode highlights:

- Host Ian Urbina takes us back to the beginning, when a young Max was teaching himself to sail and piecing together a living by doing odd jobs. That is until the gig that changed it all. After Hardberger successfully recovered a stolen ship from Venezuela, his phone just kept on ringing.

- Some of the most lucrative stealing happens in the world’s murkiest waters. Hardberger explains that his “sweet spot” is in extra-judicial areas, and walks us through his unconventional toolkit of tactics and tricks. He’s worked with sex workers, witch doctors, and many persuadable security guards. But we learn there are some laws even he won’t break, and some places even he won’t go.

- Urbina finally gets the chance to see Hardberger’s work up close, and follows him on a mission to Greece. There he hopes to repo a 261-foot freighter called The Sophia - but the job immediately proves to be more complex than even Hardberger expected. On this job, we find out where the repo man draws his line. “I like not getting killed … I like even more not going to jail in a foreign country.”

Press play and read along

Transcript

Speaker 2

It's finally summertime. I'm Nala Ayed, host of Ideas.

These last several months, maybe longer, have tested our Canadian pride.

Speaker 2 So that's why this summer we have some special programming lined up for you. We're revisiting conversations with Canadian artists and thought leaders who are moving this country forward.

Speaker 2 You'll also hear a special series I did where we traveled across the country asking people how to make Canada better. So join me for a special Canadian summer on ideas.

Speaker 3 This is a CBC podcast.

Speaker 1 I was down in Venezuela working for a company that had a ship that got seized, and I had to take it out.

Speaker 1

I had to sneak on board in the middle of the night. I had to bribe the guard to get off.

We had a very close call there and almost ran into the rocks, but managed to get out and get 12 miles offshore.

Speaker 1 But then the problem was that Venezuela reported us to Interpol as a stolen ship. So we had to sneak into a little harbor I knew in Haiti where, you know, where almost anything could be done.

Speaker 1 I'm Max Hardberger, and I steal ships for a living.

Speaker 4 I think the modern view of piracy is the kind that you see off the coast of Somalia.

Speaker 4 You know, a fast boat carrying a half dozen guys with RPGs or AK-47s approaches a huge tanker or container ship, throws a ladder over the side, climbs on board, and takes over the ship.

Speaker 4 But a lot of the piracy that happens in the world is actually white-collar piracy. It's these schemes where ships get held captive in port through bureaucratic or administrative means.

Speaker 4 The pirates are actually different groups of mortgage lenders, lawyers, ship owners, or shipping companies, and they might be sitting in an office a half a world away from the ship.

Speaker 4 And sometimes, when the ships are caught up in this kind of piracy, one side will decide to call in a repo man.

Speaker 1 I like dealing in a world where anything goes and the devil takes the hindmost, and you have to live by your wits or

Speaker 1 you have to get out.

Speaker 4 I'm Ian Urbina, and this is The Outlaw Ocean.

Speaker 4 One of the things that's fascinating me about the idea of thievery at sea is how it can manifest in ways that are really unique and often quite different from how theft usually happens on land.

Speaker 4 So, I mean, sure, you still have things like insurance fraud, sinking your own ship to make a false claim and get a payout, but some of the most lucrative types of theft at sea happen in the gray areas of the law, where what looks absolutely illegal to one party seems completely above board to another.

Speaker 4 Sometimes port officials and local judges will detain a ship under false pretenses and run up fines to an absurd degree, such that the ship owner can't actually pay off the debt.

Speaker 4 The ship is then seized and auctioned off.

Speaker 4 So to the shipowner, that feels like straight-up theft, but on paper at least, it looks entirely legal. And then what about fishing on the high seas?

Speaker 4 Does anyone really own those fish or have the right to say who can take massive amounts of them out of the ocean for profit?

Speaker 4 I mean, to some, that's also a type of stealing, in this case, stealing from the global public.

Speaker 4 But sometimes, theft at sea is a little less theoretical, and it involves getting a very large ship out of a very dicey legal situation by physically moving it out of port and into international waters.

Speaker 4 So enter the repo man.

Speaker 4 So a repo man's job on the high seas isn't too different from the job on land.

Speaker 4 Someone takes out a loan or a mortgage to buy something, they stop paying their bills and the bank who owns the mortgage or gave out the loan takes possession.

Speaker 4 If the bank is having trouble doing that, they call a repo man.

Speaker 4 This all gets a lot more complicated though when the ship is huge, hundreds of feet long.

Speaker 4 Or you're talking about a ship that, say, was bought with a mortgage from a bank in the US but is flying a flag of a country from, say, the Caribbean.

Speaker 4 Or a ship that's currently docked in a country whose property and repossession laws don't exactly match up with those of the US.

Speaker 4 So you can imagine the number of people with the skills to pull off these kinds of repo jobs is pretty small.

Speaker 4 When I looked into this world of maritime repo, the name that just kept coming up over and over again was Max Hardberger.

Speaker 1 Like many young fellows in South Louisiana, I worked on the offshore supply boats in the summers and on Christmas vacations and so on.

Speaker 1 Over the years doing that, I had earned a captain's license from the U.S. Coast Guard.

Speaker 4 Max is kind of famous in the field. He's in many ways the grandfather of the industry, and over the course of two decades, he's done about two dozen repos.

Speaker 4 He's special not just because he's been doing it for the longest time, but also because he's known to take the jobs that other repo men turn down.

Speaker 4 The guy's name is Max Hardberger. So in my head, I was envisioning envisioning a kind of hulking, tattooed, you know, six foot two guy with a lot of swagger.

Speaker 1 I bought my first sailboat the summer I graduated from college and taught myself to sail. Didn't have anybody to do it.

Speaker 1 I just opened a book on the cockpit and went out and learned by running into things.

Speaker 4 I came to find out that Max is a fairly small guy, an almost nerdy-looking academic type. He has a white beard, he's extremely well-spoken, very well-read.

Speaker 4 He looks kind of like your favorite uncle, if your favorite uncle happened to be from Alabama.

Speaker 4 I first met Max in 2016.

Speaker 4 He struck me as this sort of tin-tin type character who had done the oddest things in surprising places around the world.

Speaker 4 I mean he started flying crop dusters to help put himself through college and then he transitioned into working some odd jobs on boats.

Speaker 4 He was an adventurous guy who wanted to see the world, so he figured that sailing would let him do that. Max went to Miami, bought a ship, and from there he decided to head to Latin America.

Speaker 4 He figured he might be able to make some money shipping goods in and out of Haiti.

Speaker 1 That didn't work out,

Speaker 1 but it was an educational lesson.

Speaker 4 So Max fell back on his captain's license and began jumping from ship to ship, taking whatever work he could find.

Speaker 4 That's when he got this job in Venezuela, recovering the stolen ship, the one you heard about earlier.

Speaker 4 He snuck on board, sailed the ship to Haiti, and hid its identity.

Speaker 1 You have to take a grinder and you have to grind off the raised, welded-on names on the hull in three places, and then you have to weld on a fake new name.

Speaker 1 You have to take all the ship's documents and they have to be altered. If you've done it right, then it looks like the ship's original documents and you can get past the inspectors.

Speaker 1 You have to deliver the ship to some place where the officials will not inquire too carefully into the ship's past. So we took her to Puerto Limon, Costa Rica and sold her.

Speaker 1 Sold her to ourselves of course.

Speaker 4 By selling the ship to themselves, or as it's called in the maritime world, scrubbing the bottom, Max and his partners were able to wipe out its previous trail of ownership and erase any official record of its previous identity.

Speaker 4 Max thought the repo in Venezuela was a one-time thing, so he went back to the U.S. to work as a shipping consultant.

Speaker 4 But the maritime community is pretty small and word traveled fast about the job he'd pulled off. And then his phone started to ring.

Speaker 1 The next thing I knew, a fellow from the Bahamas was losing his ship to a corrupt shipyard in Trinidad.

Speaker 1 And I knew that shipyard and I knew its reputation and I knew that he would never get his ship back legally. It was a bad situation down there, and I had no way of sneaking it out under power.

Speaker 1 So we just had to cut the deck lines and let the ship drift to international waters where I had a tugboat waiting.

Speaker 1 I didn't think of it as a career. It was just an issue of not letting the bad guys get away with it.

Speaker 4 Among Max's many interesting jobs, he was a high school history teacher.

Speaker 3

I was 16 years old, getting ready to turn 17, and I had just enrolled in a world history class at high school. Max was my teacher.

And I found him to be just a fascinating character.

Speaker 3 Everybody in the class did. And we came to the conclusion that he was a CIA agent on the run from the Russians and took refuge in the small suburban town outside of New Orleans.

Speaker 3 But what prompted that was things like, on show-and-tell day, he brought in a crossbow.

Speaker 3 My name is Michael Bono. I am managing director of Vessel Extractions LLC.

Speaker 1

I taught Michael history, and then we had no contact for many years. And I went on and got a law degree and became a maritime lawyer.

He went on to become a maritime lawyer.

Speaker 3 So when I practiced law at a specialized maritime firm in New Orleans, one of the things I did was handle ship repossessions on behalf of major shipping lenders.

Speaker 3 And it gave me an idea that maybe there should be a dedicated service to help banks handle the logistics of a ship repossession. But I didn't have an operations guy, somebody with technical expertise.

Speaker 3 I needed a man who knew the sea.

Speaker 4 By pure coincidence, Bono stumbled across a copy of a book called Freighter Captain, and he realized he knew the author.

Speaker 3 That's my world world history teacher, Max Hardberger.

Speaker 4 Writing is another one of Max's many interests. He actually has an MFA in fiction and poetry from the University of Iowa.

Speaker 4 In Freighter Captain, Max recounts some of the more outlandish stories from his time captaining an aging ship in dangerous parts of the world.

Speaker 1 So I said, this is perfect. I looked him up.

Speaker 3

I called him. I said, Mr.

Hardberger, This is Michael Bono. Do you remember me?

Speaker 1

He was looking for someone to be on the operational side. So I said, well, I'm already doing it.

That's fine. Let's do it.

So we formed Vessel Extractions LLC.

Speaker 3 What we do is we get ships out of bad places. And we can do that on behalf of banks who have a mortgage on a vessel.

Speaker 3 We do that for ship owners when they run out of options and they come to us as basically a last resort.

Speaker 1 Yeah, you would do anything you can other than hire us.

Speaker 3 Why do people come to us instead of elsewhere? We operate in the extrajudicial area. That's our sweet spot.

Speaker 4 One of the main criticisms aimed at RepoMen is that the work they do undermines local authorities. Often they're seen as exerting vigilante justice.

Speaker 4 And that's an especially big problem in places where the laws are already a bit wobbly. you know, places like Haiti, a place that Max really likes to work.

Speaker 4 And so when you have these these outsiders, wealthy white Westerners in particular, coming in and doing things that are on the edge or across the line of the law, it really does further erode any legitimate authority that the government and local police might have.

Speaker 4 I raised this point with Max, and he didn't totally disagree.

Speaker 1 All corruption contributes to corruption.

Speaker 1 And no matter how minor my corruption might be in the overall scheme of, say, Haitian or Venezuelan corruption, no matter how corrupt they are and how minor my corruption might be, there's no question.

Speaker 1 I am circumventing the laws of shipping and I'm circumventing, I certainly am circumventing the overall law of that country. Even in Haiti, even though the laws are not enforced, Haiti has law.

Speaker 4 You know, Max is a perfect example of the outlaw ocean in the sense that he has this odd relationship with the law.

Speaker 1 I will not break any U.S. laws.

Speaker 1 That's a promise I made to my bar association, and I've been very faithful to that promise so far.

Speaker 1 As far as breaking the laws of uncorrupt countries, they have systems of laws where my client can go to the court and seek redress in the system of courts.

Speaker 1 So that's what Michael and I tell them to do when they have an issue in a country with law. The only time I'll take on a job is when the law has failed my client.

Speaker 4 Do they prioritize some people's laws and some specific laws over others? For sure. Are they breaking laws to protect other laws? Quite possibly.

Speaker 4 Oftentimes, they get pulled in because some other players have clearly broken or bent the law to do something that's completely extra-legal, illegal, or immoral.

Speaker 3 Despite Max's use of words like stealing ship out of port and things of that nature, you know, that's shorthand for what we do.

Speaker 4 Before vessel extractions takes on a job, they do some vetting, they do due diligence. They want to figure out the basics, like, does the client have a legitimate claim on the ship?

Speaker 3 I remember someone in naval intelligence said that, you know, there are not a lot of rules in this area, but to the extent there are rules, Max follows them.

Speaker 4 Most mortgage agreements between banks and ship owners tend to have a self-help provision.

Speaker 4 And what that means is that the ship owner, if they default on the mortgage, then the bank has a right to exert ownership and they can appoint someone, an individual or a company like Vessel Extractions, to go and get the ship back.

Speaker 4 And so Max comes in to try to relocate the ship to another another system of law that is, in their view, more fair, or at least more favorable to their clients.

Speaker 3 Max is someone, he's an extraordinary person, and he has an incredible sense of right and wrong and of justice. And when he sees something that

Speaker 3 seems wrong to him, he is determined to take action, even if it puts himself in harm's way.

Speaker 3 The big example that I always cite is for the job that really put us on the map in 2004 in Haiti with the Maya Express extraction during the middle of the Haitian rebellion.

Speaker 3 It's a low-level civil war, I guess you could say.

Speaker 4 The Maya Express job revolved around a ship that was being held somewhere in Haiti. The mortgage was owed money and wanted to take possession of the ship, but there were a few complications.

Speaker 1 The Mortgage didn't know where the ship was, and so he hired us to find the vessel first.

Speaker 1 And interestingly enough, I called my friend Ronald in Haiti and said, oh, we're looking for the Maya Express. He said, well, Captain, the Maya Express is in Miraguan.

Speaker 4 Miraguan is a small Haitian port village where Max actually owned some property. Max lives in Haiti part-time and has done a bunch of jobs there.

Speaker 4 It's the sort of place that has a lot more art than science in how people live and survive.

Speaker 1 Oh, there's a lot of things you can do in Haiti that you can't do anywhere else, like kill people and get away with it.

Speaker 1

Everything to do with Haiti is completely corrupt. Haitian ship owners are scoundrels.

Haitian shippers are scoundrels. Haitian receivers are scoundrels.

Speaker 1 A ship captain finds himself in the middle of a nest of scoundrels.

Speaker 4 He knew the locals and was quickly able to figure out what had happened.

Speaker 4 A local justice of the peace had issued an order to seize seize the Maya Express, which would keep it docked until it could be sold at a judicial auction.

Speaker 4 Selling the ship at auction would quickly bring a lot of money into Miraguan, and everyone with a connection to the port stood to profit.

Speaker 4 If they were going to get the ship out of Haiti, they'd have to work pretty fast.

Speaker 3 We had to do something in two days' time.

Speaker 1 We could not wait because the judicial auction was coming on Thursday. Once the auction takes place, then I cannot act act because the ship actually belongs to the buyer at the auction.

Speaker 1 The situation there, though, was that the country was in revolution. All the police had run up in the hills and tore off their uniforms and were hiding out.

Speaker 1 And all the police stations that you passed on the road down to Miriguan had been burned, and police cars overturned and burned out. And the roads were all controlled by bandits.

Speaker 3

We have a system where Max makes regular hourly cell iPhone calls. And he got to the point where we're getting getting close to the operation beginning.

And he says, Michael, we're about to start.

Speaker 3

If I don't make the next call, that means I'm probably dead. Please tell my wife and don't send anyone for the body.

It's not worth it. And I remember the hair standing up on my arms.

Speaker 1

The ship was at anchor. It had two anchors out in front, and then it was tied with ropes at the stern to the old Reynolds dock.

And there were two Dominican guards on board.

Speaker 1 But those Dominican guards had been selling diesel off the ship, of course, without the owner knowing.

Speaker 4 Max had his fixer Ronald go aboard the Maya Express and tell the watchman that he knew someone looking to buy some of the ship's diesel. The guards met Max on the dock and agreed to a price.

Speaker 1 I was going to have to use a tugboat to tow it.

Speaker 1 So to keep them from being suspicious, and seeing a tugboat approach, I told them the tugboat would be coming to get diesel, and we had to do it at night so the Haitian authorities

Speaker 1 wouldn't know about it and wouldn't know that they were selling it and they agreed to that of course.

Speaker 4 Max left Miraguan and headed to Port-au-Prince to quickly put together another plan. Later that night he headed back to the Maya Express and brought some extra guys.

Speaker 1 I hired two SWAT team members from Port-au-Prince and they had two Uzis

Speaker 1 and so I brought them on the dock.

Speaker 1 And so as soon as the guards got off the ship, I told the guards that I would pay them $300 each for the belongings they had left on board, but they couldn't go back on board.

Speaker 1 They were happy with that and they took off as quickly as they could.

Speaker 4 With the guards gone, Max hitched the Maya Express to his tugboat and his small crew set to work cutting the anchor chains.

Speaker 1

Unfortunately, it was a full moon. and not a cloud in the sky.

As they were cutting the anchor chain, the entire bay was lit up. So people came running down from the hills to see what was going on.

Speaker 1 And I had those those two guards, whenever somebody came down to the dock, keep them on the dock and not let anybody leave until we had finished cutting the anchor chain.

Speaker 1 Then the tug towed it out and we towed it to the Bahamas.

Speaker 3 And he is putting himself in harm's way. And he was willing to possibly sacrifice his life for this particular job because of his sense of justice.

Speaker 3 He knew that the ship was stolen from the owner and we had to step in and do something about it.

Speaker 1

It was the worst possible condition for an extraction. And it was pretty hairy.

But we managed to get it out.

Speaker 5 Kathleen Folbig was known as Australia's worst female serial killer.

Speaker 5 She was convicted of killing her four infant children until a scientist uncovered the truth.

Speaker 6 Scientists want to know the truth and want to get to the bottom of things, particularly in a case like this where science can solve it.

Speaker 5 The Lab Detective is a story of a shocking miscarriage of justice and an investigation into why Kathleen's story might not be the last. Listen wherever you get your podcasts.

Speaker 4 I'd been super fascinated in Max for a long time and when I heard that he had a job in Greece coming up, I leapt at the opportunity to go with him and see him work.

Speaker 4 The ship that Max was supposed to repo was a 261-foot freighter called the Sophia.

Speaker 1 The first thing I knew about the vessel Sophia was that there was an issue with the vessel's mortgageee, and we had been hired to try to get the ship out of Greek waters.

Speaker 4 Max's job was to get on this specific ship, to get it out to the high seas somehow, and then once it was on the high seas, take over the ship, take command of it from the captain, and sail that ship to a more favorable port where the laws would give the mortgage lenders on the ship a better chance at succeeding in a court fight.

Speaker 4 If the ship got stuck in Greece, there were two groups who stood to lose.

Speaker 4 First was the ship's mortgage lender, which is who hired Max, and this was this New York firm called TCA Fund Management Group, and they were owed over $4 million by the ship owner.

Speaker 4 The second was a management company called New Lead,

Speaker 4 which ran the ship's day-to-day operations, including looking after the crew. And these guys were owed tens of thousands of dollars in back wages.

Speaker 1 When I got there, the man I met up with who was most helpful was the crewing agent. He was a Greek man and a very nice fellow, and we became good friends.

Speaker 1 And he was very helpful because he was very concerned about the Filipino crew, who had been going without payment for months and months and months on a ship that was in poor shape and getting in poor shape by the month.

Speaker 4 So the crew is one concern, but the ship's cargo is another. The Sophia was carrying something called bitumen, which is essentially liquefied asphalt.

Speaker 4 Bitumin is used to build roads, so there's a lucrative market for it all over the world.

Speaker 1 The ship has to maintain a lot of heat in the cargo through steam pipes in order to keep bitumen liquid.

Speaker 1 If the ship's machinery goes down, the bitumen will harden up to asphalt and it cannot be gotten out. In other words, that's the end of the ship.

Speaker 1 So it was critically important that the ship be taken to some port where it could get the maintenance it needed because the ship was on its last legs.

Speaker 1 Luckily, the cargo heating apparatus was still working.

Speaker 4 When I got to Greece, the job seemed more chaotic than I expected it to be. It wasn't clear to me, and I wasn't sure it was clear to Max,

Speaker 4 when we were going to launch and in what direction or how we would know our queue had come.

Speaker 4 The risks here were pretty intense.

Speaker 4 Number one, the phase of getting the ship from its anchorage out to the high seas is extremely dangerous because at any given moment, the authorities, you know, Greek authorities, Coast Guard, the port captain, anyone, could realize what's going on and they would essentially send the police out to arrest Max.

Speaker 4 And that's a huge problem in Greece, partially because of the cast of characters tied to this ship, who were essentially mafia.

Speaker 4 These were really connected, really well-financed, politically powerful players in Greece.

Speaker 1 I've heard about the owner's background, which was quite questionable, and that figured into my plans.

Speaker 4 Sophia was owned by a guy named Nicolas Zolatas, who at the time was a widely feared shipping magnate with friends in pretty high places.

Speaker 4 Zolatas was caught up in a corruption scandal surrounding the collapse of the Cypriot banking system, and he'd been arrested and extradited to Cyprus on corruption charges a few weeks before I got to Greece.

Speaker 3 He was still very powerful. He was still a Greek ship owner with a vessel, his vessel, in Greece, with a large support network in Greece.

Speaker 3 So we were facing a situation where the mortgage was looking at possible hometown justice being used against them.

Speaker 3 And they desperately wanted to get the ship out of Greece and into a more favorable jurisdiction, one that follows British law. First choice was Gibraltar.

Speaker 4 In the maritime world, Greece is a superpower. Roughly half of the country's prominent shipping families come from one island called Chios, which is this minuscule, mountainous little spit of land.

Speaker 4 It's like five miles off the coast of Turkey, and it's for many years been this outpost of underworld activity.

Speaker 4

Zolatas was from Chios, a third-generation ship owner. He had his tentacles in banking and politics as well as shipping.

And he was as respected as he was feared.

Speaker 4

You really didn't want to go up against this guy. I figured it made sense for me to go to Chios and see what the island was like.

And so I flew there and began poking around.

Speaker 4 One person I talked to in Kios, you know, said to me quite bluntly, he's not someone you should be asking questions about. It's not safe.

Speaker 4 Zolatas owed a lot of people money, but until his arrest, no one had the spine to demand repayment.

Speaker 4 Once he was arrested and extradited, it was open season on everything he owned.

Speaker 4 By the time Hardberger touched down, Four of Zolatas' ships had already been seized in other ports in the world.

Speaker 4 Creditors were lining up at the Greek courthouse to put liens on the Sophia in particular.

Speaker 3 So, in the case of the Sophia, creditors would come in, they'd assert liens, the court would issue an arrest warrant preventing the ship from leaving and mobilizing it.

Speaker 3 Then, the mortgagee would have to come in and pay off those liens because the liens that were being paid off outranked the mortgage lien.

Speaker 4 A big reason why Max's clients, the bankers that owned the mortgage on the SOFI, wanted to get the ship out of Greece was because of this concept called lien ranking.

Speaker 4 That's the order in which debts get paid off, and it varies from country to country.

Speaker 4 Greece prioritizes smaller local liens, while Gibraltar and other countries that follow British common law put big debts like mortgage defaults at the top.

Speaker 4

The SOFIA was stuck in Greece until all of those small local debts were paid off. And the longer it sat, the more debts piled up.

To leave port, the Sophia needed something called a clearance.

Speaker 1 A clearance is your permission to depart a port and you cannot get the clearance from the captain of the port until all the ship's debts have been paid.

Speaker 4 And because this was Greece, not Haiti, a lot of Max's usual tactics weren't going to fly.

Speaker 1 If we had attempted a surreptitious extraction, then all of those things would have been moot.

Speaker 1 I would have just figured out some way to get out without a clearance in the dead of night, in the middle of a storm, or whatever.

Speaker 4 This meant sending a local agent to the courthouse in Piraeus and paying off dozens of small claims against Solatas that were keeping the Sophia tied up in port.

Speaker 3 But then it was like a game of whack-a-bowl. It was

Speaker 3 you pay off one set of claimants, and as soon as that happens, then another set of claimants pile on. It's like blood chumming the water and the sharks start coming.

Speaker 3 And so you have to find ways to stop the hemorrhaging.

Speaker 3 And one way that we did this in the Sophia case was by making sure to pay off liens on a Friday afternoon and then immediately making arrangements to sail the vessel out of port.

Speaker 4 Paying the debts and securing the Sophia's clearance on a Friday afternoon would give them a full weekend to get the Sophia into international waters before the cycle of claims and liens started again on Monday morning.

Speaker 3 It's a matter of timing. And if you don't get the timing right and there's some kind of glitch and you can't free the vessel until the next weekend, well, you might be in for a long stay.

Speaker 4 So Max and Bono needed to get the SOFI out of Greece and get it somewhere that it could be repaired so the bitumen could eventually be delivered.

Speaker 3

We are caught in the middle of this because we have a client that wanted action. That's why they hired us.

I remember one heated conversation.

Speaker 3 I don't recall who said these words, but I do remember the words. that what they were looking for from us was pirate action, quote unquote.

Speaker 3 We had difficulty explaining that you can't do what you would do in Haiti, for example, in Greece. You had to follow the rules.

Speaker 4 Max and Bono were playing by the rules on the Sophia job, and that made things a little bit complicated. It meant Max couldn't sneak on board to do reconnaissance.

Speaker 4 Normally, that would be one of the first things he'd do. What condition is the ship in? Do the engines work? Can it get out of port under its own power?

Speaker 4 And most importantly, what's the state of mind of the crew and the captain?

Speaker 4 These are all things Max needs to know, and over the years, he's fine-tuned his bag of tricks for getting on board to find them out. Whenever possible, Max prefers to talk his way on board.

Speaker 4 He's not a guy that tries to muscle his way or to use guns.

Speaker 1 You know, I've always found that if you present yourself in such a way that there is nothing out of sorts, there's nothing that's questionable, that in all aspects you resemble what you are claiming to be or you want to be taken as.

Speaker 1 Then most of the people in this business are so preoccupied with their own problems that they don't look beyond what they first see. They will pretty much accept you for what you claim to be.

Speaker 4 He's got a plethora of fake uniforms and official sounding business cards that he can pull out at any given moment, show whomever to convince that he's legit.

Speaker 1 You say, I'm Port State Control. I'm here to inspect your ship, Captain.

Speaker 1 When is your lunch ready?

Speaker 1 And as soon as you say that, he assumes

Speaker 1 you're the local and

Speaker 1 you're ready to have lunch and then take a leisurely look around the ship. Other ways to get on board are to befriend somebody on board.

Speaker 1 You go to the local bar, you make friends with the prostitutes in the bar, you make friends with the crew where they're hanging out, and get yourself invited on board for just for social reasons, if no other reason.

Speaker 1 And then there are more surreptitious ways of getting on board too. Like you can have a local bring you onto the oceanside at night, dead at night, without a moon, with no lights.

Speaker 1 Then you actually can pull yourself up the anchor chain and get on board that way.

Speaker 4 Max has an interesting toolkit of tactics he uses to get the job done.

Speaker 4 In years past, he's plied guards with booze, distracted them with prostitutes he mentioned to me the prostitutes are the best actors because they've got a lifetime of practice

Speaker 1 well that's their job

Speaker 1 they have to pretend to be attracted to their to their clients i one time hired a lady in the dominican republic who uh was a great actor and i had to hire her to to convince a guard on board to take a drink which he obviously shouldn't be doing when he's on board.

Speaker 1 But she did a great job. She convinced him to take a drink that was loaded with,

Speaker 1 I forget the name of the drug, but anyway, he went to sleep on deck, got carried down to the dock, and paid her off and told her she would soon be a star in Hollywood and got the ship out.

Speaker 4 Max said that the worst thing he'd ever done to get a guard off a ship was to pay someone to lie to the guard, saying that the guard's mother had just been hospitalized.

Speaker 4 At times, he's had to use some even less conventional tactics, like using a curse to keep people away and hiring a shaman.

Speaker 1 When I was a ship captain, I got tired of thieves stealing stuff off my ship at night.

Speaker 1 So I hired a witch doctor to come on board and put the powder on the ship, as they like to call it, you know, to sprinkle some stuff out of his snuff box.

Speaker 1 And of course, the bad thing about it was that, one, is all the girls ran off the ship. My crew didn't like that.

Speaker 1 And then the stevedores wouldn't come on board to unload the ship when they heard about the witch doctor. So my owner got charged a half day's delay for the stevedores not coming on board.

Speaker 4 Most often, he exploits the crew's desperation. He says that's the easiest way to get onto a ship.

Speaker 1

Sometimes you can offer to help the crew. You can tell the crew, well, I'm sorry for you guys.

I know it's really bad. You know, here, let me come on board and see if I can help.

Speaker 1 Quite often, these ships are for sale. And the crew on board, even if they haven't heard about a particular buyer, they are so hopeful that the ship will be sold.

Speaker 1 And when the ship is sold, they'll get paid that they will welcome a buyer's inspector on board. So then you can take all the photographs and video you want.

Speaker 1 Nowadays it's much easier because I have a pair of glasses that record so I just have to show up wearing my glasses and I can record everything I see.

Speaker 4 During these tours, sometimes he'd go to the bridge and he'd leave a tape recorder running in some corner where no one would notice it.

Speaker 4 He'd continue on the tour, leave the bridge, and in that interim, officers would probably, you know, show up at the bridge and say things that Max wasn't supposed to hear, but was nonetheless captured on the tape recorder.

Speaker 4 At the end of his tour, Max would swing back by the bridge and pick up the tape recorder and see what intel he had netted.

Speaker 4 So, Max is in Piraeus and the clock is ticking. I'd been there for a few weeks, mostly just drinking way too much coffee and losing my mind waiting for the operation to go down.

Speaker 4

Everyone agreed that they needed to get the Sophia out of Greek waters. The issue now was where to take it.

Max's clients wanted to sail to Gibraltar.

Speaker 4 The ship's management company, the other side in the dispute, had connections in Libya and Egypt and wanted to take the Sophia there.

Speaker 4 With the weekend approaching, it was time to make a move. So all the parties agreed to get the Sophia to international waters and settle things once they were on the high seas.

Speaker 4 So they cleared the liens against the Sophia on a Friday afternoon and gave Max the go-ahead to board.

Speaker 1 I had no real preparation for the night that I got a call that said, go to the waterfront in Piraeus, get on a crewboat.

Speaker 1 The crewboat is going to take you to the ship and you're going to get out of Greek waters as fast as possible.

Speaker 4 Remember, this was the first time Max had actually been on the Sophia. He had no idea what kind of condition the ship was in, or if it could even get out of port under its own power.

Speaker 4 He'd also never talked to the crew of the Sophia nor its captain. He couldn't get the ship out unless they agreed to go along with the plan.

Speaker 4 And just as a side note, the terms master and captain in this case are interchangeable. Master just means someone with a captain's license who's actively in charge of a ship.

Speaker 3

So Max got on board the vessel and he went around, first of all, looking at the condition of the vessel, seeing if it's seaworthy. Then he had to assess the crew.

And

Speaker 3 he uses techniques like just being a regular guy with the crew and

Speaker 3 having a few beers and telling stories and trying to get a read for them and what their feeling was.

Speaker 3 And the impression we got was that they were all on board. They hadn't been paid in months.

Speaker 3 And here we were coming and offering them to pay everything that they were owed and give them a plane ticket home. And the master, the captain, was also on board with this plan up until a point.

Speaker 3 And that was the glitch in this operation.

Speaker 4 So as this whole thing is unfolding, I'm essentially sitting in a skiff, which is a small rubber boat with an outboard motor, and we're hiding behind another much bigger vessel that's parked alongside the Sophia.

Speaker 4 I had hired a boat driver and a videographer for a couple days, so I was with a team. And there's this whole negotiation that's happening on board the Sophia.

Speaker 4 I need to stay close to the Sophia so that I can maintain radio contact with Max and keep track of what's going on.

Speaker 4 Max, meanwhile, is on the bridge of the Sophia, trying to hash out with the captain the next steps and trying to convince him to race to the 13 mile mark, meaning to get to the high seas.

Speaker 1 My first instruction to him was just to get out of Greek waters.

Speaker 3

Piraeus is a port that's near Athens, Greece. And if you look at a map of Greece, you see a coast that's dotted with islands.

And imagine maritime boundaries. extending 12 miles from each island.

Speaker 3 So if you look at the map, you see that Piraeus is really tucked in, and the ship had to sail all past all those islands before it could reach international waters.

Speaker 3

Something like, I think it was like a 14-hour voyage to get to international waters. There's no place to hide.

You can't make a mad dash like you could in other jurisdictions.

Speaker 4 We'd been discreetly shadowing the Sophia on the water for about four hours, trying to stay close enough to maintain radio contact.

Speaker 4 But we were at risk of running out of gas, so we had to turn back and from then forward rely on a satellite phone to communicate with Max.

Speaker 3 Everything was going fine. Everything was going according to plan.

Speaker 3 And as we got closer to international waters, that's when Max gave the instruction to the master that he was taking over command of the ship.

Speaker 3 under the authority granted to him by the mortgageee and instructed the master to sail the vessel to Gibraltar.

Speaker 3 The master did not like those orders and immediately consulted with the vessel's operator and received a conflicting order, do not sail to Gibraltar under any circumstances.

Speaker 3 So we were in a limbo situation here.

Speaker 1 The master got cold feet when he was threatened with jail for barretry. Baratry is the technical term for when a master disobeys his owner's orders.

Speaker 3 He was paralyzed with fear. He then sailed the ship in circles and basically told the size, you guys work it out and then let me know what to do.

Speaker 3 I'd rather take no action than take some action that could jeopardize my license.

Speaker 1

He was very new as a master. This was his first or second job as captain as opposed to chief officer.

He was being whipsawed by a bunch of different interests.

Speaker 1

It was a situation that for him was fairly intolerable and became pretty intolerable for me too. too.

So we dropped anchor behind this uninhabited island without a blade of grass on it, just a rock.

Speaker 1 And there we spent at least a week while I became less and less popular with the crew, even less popular with the captain, and found myself at one point wading through sewage to get to the hospital berth where I hold myself up.

Speaker 4 That's when the weather turned harsh and the seas got rough.

Speaker 1 It was a bitter, bitter winter in the Mediterranean, which can be a cold and rough place. And we were going against the seas, and so it would have taken us a very long time to reach Gibraltar.

Speaker 3

This process dragged out for many days at sea. Max was stuck on the vessel, couldn't get off.

He was essentially a prisoner there.

Speaker 1 You can imagine the frustration of lying in your bunk for 10 straight days when you're used to seeing things get done.

Speaker 1 And also not knowing what's going on on shore, not having any idea what's behind the sometimes contradictory orders that I'm getting.

Speaker 4 A lot of the legality of what Max is doing depends on where the ship ends up. Is Max legally repossessing a ship on behalf of the bankers, or is he stealing it from someone who has a more valid claim?

Speaker 4 Different courts are going to have different answers to that question.

Speaker 4 So the stakes here for Max are pretty high.

Speaker 1 If the ship went to Egypt, where Egypt is as corrupt as any North African country,

Speaker 1 I and the crew, and maybe especially I, could find myself in an Egyptian jail, and the Egyptian court would give the ship to

Speaker 1

the owner. Even more so Libya.

Libya, of course, would be even worse in that respect than Egypt. So we could not let that happen.

Speaker 1 If that had happened, then I would have had to have gotten off at the nearest island.

Speaker 1 I don't care if it's a rock with no water on it, and just give me a five-gallon pail of water and put me off at this rock because I'm not going to Egypt and I'm not going to Libya.

Speaker 4 While Max waited things out on board the Sophia, Bono kept negotiating on behalf of the bankers and was eventually able to reach an agreement.

Speaker 3 I remember seeing it described as being extortion, where the mortgagee had to make a substantial payment of some monies that were claimed owed by the operator.

Speaker 3 Once that payment was made, then the operator finally gave authorization to the master to sail. This time, not to Gibraltar, but to an alternative port in Malta.

Speaker 1 Well, yes, it was frustrating. However, I like not getting killed.

Speaker 1 So

Speaker 1 in one sense, it was a very nice experience and quite unusual for an extraction.

Speaker 1 And I like even more not going to jail in a foreign country.

Speaker 4 Max is getting older, and it's easy to see him as a kind of relic of a different era.

Speaker 3 These jobs are not frequent.

Speaker 3 We get calls about ships in trouble and we go on the ground and assess the situation, provide options to the client, and the client decides it's too risky or in the meanwhile they worked it out with the opposing party and the repossession doesn't actually go forward.

Speaker 3 We do all the legwork, but we don't follow through. When we do follow through, it's usually because we are an option of last resort.

Speaker 3

So, when we do act, when we take repossession action, you actually get it out of court. It's infrequent.

And it's even more so now that Max is semi-retired, writing books

Speaker 3 in his seclusion in the backwoods of Mississippi, enjoying his life. A few years ago, he said, called me up and said, Michael, I don't know, maybe we need to reduce our efforts.

Speaker 3 Just the prospect of me spending my remaining days in a third world prison are not too enticing. So we pared things down, but occasionally we get that call and he springs into action.

Speaker 3 He says, I have a passport in hand, ready to travel.

Speaker 4 I asked Max how much longer he thinks he can keep doing this work.

Speaker 1 Well, I don't know. As long as I can run to the end of the dock and jump in the water and swim to safety, I guess I will.

Speaker 4 I've come to realize that there's something about the sea that attracts characters like Max Hardberger.

Speaker 4 There are few laws, big money, and plenty of opportunity if you're quick-witted and know your way around the ship.

Speaker 4 And who's to say who's a thief and who's not when it's hard to even define what stealing is out there?

Speaker 4

Max says he follows the laws of the U.S., he says he obeys his own sense of right and wrong. He's free to make some of that up as he goes along.

He's a free agent operating in a poetic space.

Speaker 4 Make no mistake here though, the folks on the other end of Max's extractions think of him as a thief, and even some of his own clients imagine him to be some sort of swashbuckling pirate.

Speaker 4 Ultimately though, at least in my opinion, which side of the law you're on depends on which shore you're viewing it from.

Speaker 4 Next time on the Ottawa Ocean, a whistleblower peels back the shell on India's shrimp processing plants.

Speaker 4 Josh Farinella thought he'd been offered his dream job, managing a shrimp processing plant in southern India. It turned out to be a nightmare.

Speaker 4 Behind the friendly, wholesome packaging exists a world of inhumane working conditions and egregious health concerns. You'll never look at all-you-can-eat shrimp the same way again.

Speaker 4

This series is created and produced by the Outlaw Ocean Project. It's reported and hosted by me, Ian Urbina, written and produced by Michael Catano.

Our associate producer is Craig Ferguson.

Speaker 4 Mix sound design and original music by Alex Edkins and Graham Walsh. Additional sound recording by Tony Fowler.

Speaker 4 For CBC podcasts, our coordinating producers Fabiola Carletti, senior producer Damon Fairless.

Speaker 4 The executive producers are Cecil Fernandez and Chris Oak.

Speaker 4

Tanya Springer is the senior manager, and R. F.

Narani is the director of CBC Podcasts.

Speaker 4 This is Ian Urbina, the host of this show and the executive editor of the Outlaw Ocean Project.

Speaker 4 I just wanted to take a second to let you know that if you're enjoying the show, you can find more stories like this one on our website, theoutlawocean.com.

Speaker 4 The Outlaw Ocean Project is a non-profit journalism organization that produces investigative stories about human rights, labor, and environmental concerns in the ocean around the world.

Speaker 4 On our site, you'll find print articles, interactive features, documentary films, and full seasons of our podcasts.

Speaker 4 So please take a moment, visit the outlawocean.com and support this important not-for-profit journalism.

Speaker 3 For more CBC podcasts, go to cbc.ca/slash podcasts.