S2 E2: A place “worse than hell” (Libya Pt.2)

The Libyan Coast Guard is doing the European Union’s dirty work, capturing migrants as they attempt to cross the Mediterranean into Europe and throwing them in secret prisons. There, they are extorted, abused and sometimes killed. An investigation into the death of Aliou Candé, a young farmer and father from Gineau-Bisseau, puts the Outlaw Ocean team in the cross-hairs of Libya’s violent and repressive regime. In this stunning three-part series, we take you inside the walls of one of the most dangerous prisons, in a lawless regime where the world’s forgotten migrants languish.

Ep. 2 highlights:

- The EU has claimed they play no role in this migrant crisis, even as they provide boats, buses, petrol — even the tablets the Libyans use to count up their captives.

- Once captured and counted, those migrants are often held in a network of secretive prisons run by competing militias, where exploitation, abuse, and death are common. They are also routinely “rented” as everything from farm labour to soldiers in battle.

- Aliou Candé was sent to a prison, where he died at the hands of prison guards, while trying to protect himself from a melee. “I’m not going to fight. I’m the hope of my entire family.”

Press play and read along

Transcript

Speaker 1 Hi there, Steve Patterson here, host of The Debaters. We're very excited to be celebrating our show's 20th anniversary, and we can't believe our years either.

Speaker 1 If you're a longtime fan, thanks for being a glutton for punishment. If not, come laugh with us to all the topics you didn't even know were funny until we started arguing about them.

Speaker 1 Find us wherever you get your podcasts for extended episodes and special behind-the-scenes features you won't hear on any other airwaves.

Speaker 1 The Debaters' 20th anniversary season: Comedy worth arguing about.

Speaker 2 This is a CBC podcast.

Speaker 2 On June 30th, 2021, an NGO called SeaWatch received a distress call from a vessel attempting to cross the Mediterranean Sea.

Speaker 2 The call came from a blue wooden boat with an open top and a small outboard motor. On board were at least two dozen migrants, most likely trying to make the journey from Libya to Malta.

Speaker 2 Part of SeaWatch's mission is to commission ships to help rescue migrants in these waters. What you're hearing is audio recorded by SeaWatch.

Speaker 3 So-called Libyan Coast Guard, so-called Libyan Coast Guard. This is Hotel Bravo Ghost Mike Mike on channel 7-2.

Speaker 3 You are endangering the people.

Speaker 2 The video was filmed by Seabird, a SeaWatch airplane, as it circled over the Mediterranean. It was about 15 miles into the Maltese search and rescue area, well outside Libyan waters.

Speaker 2 Shortly after Seabird arrived on the scene, it spotted a Libyan Coast Guard vessel, the Raz Jadar, closing in.

Speaker 3 You are getting too close to the case.

Speaker 2 Over.

Speaker 2 You can hear the aid worker from SeaWatch make radio contact with the Libyan Coast Guard.

Speaker 2 The situation quickly worsens.

Speaker 2 They're shooting into the water, probably trying to hit the migrant vessel's engine to disable it.

Speaker 3 So-called Libyan Coast Guard, please keep more distance. Don't shoot at the people.

Speaker 3 Keep a distance to the boat. Over.

Speaker 4 This is really bad.

Speaker 4 They're shooting again.

Speaker 3 So cried Libyan Coast Guard, stop shooting in the water.

Speaker 2 When the Libyan Coast Guard is unable to shoot out the migrant vessel's engine, they try to snag the engine with heavy ropes attached to a buoy.

Speaker 4 Ah no.

Speaker 4 no, okay, they're trying to go in front of the boat now, and they have the chain in the water. Okay, so that the boat is sliding into the chain.

Speaker 4 It's gonna be very awful.

Speaker 2 Finally, the Libyan Coast Guard resorts to throwing sticks and other debris.

Speaker 4 Were they throwing sticks at the boat?

Speaker 4 They got them, yeah.

Speaker 2 The Raz Jaddar buzzes by the migrant vessel in an attempt to capsize it.

Speaker 2 After 90 minutes of attempting to disable the migrant small boat, the Libyan Coast Guard turns south and leaves the scene.

Speaker 2 These migrants were able to avoid capture by the Libyans and reach Italian waters. Thousands of other migrants that attempt a similar crossing aren't so lucky.

Speaker 2 They're successfully intercepted and brought forcibly back to Libya.

Speaker 2 From there, those migrants are often held in a network of secret prisons run by militias where exploitation, abuse, and death are common.

Speaker 2 Aliu Kande, a young migrant from Guinea-Bissau, was among the unlucky ones. This is his story.

Speaker 2 I'm Ian Urbina, and this is the Outlaw Ocean.

Speaker 2 Aliu Konde was a 28-year-old from a small village in Guinea-Bissau, one of the poorest countries in Africa.

Speaker 2 Like hundreds of thousands of other migrants from sub-Saharan Africa, Aliu decided to leave his village and make the dangerous journey across the Mediterranean to Europe.

Speaker 2 His hope was to get a job, send money back home, and provide a better life for his pregnant wife, two small children, and parents.

Speaker 2 He spent months traveling across Africa and eventually landed in Tripoli, Libya. It's a popular launching point for migrants who can't afford shorter, safer, more expensive options.

Speaker 2 Aliu found under-the-table work as a house painter. After about three months, he had saved enough money to pay a trafficker to take him to Italy.

Speaker 2 There are a lot of launching places that migrants can leave if they're trying to get to Europe and they're crossing the Mediterranean.

Speaker 2 They can leave from Algeria, they can leave from Tunisia, they can leave from Morocco, but the most popular route for migrants is to leave from Libya.

Speaker 2 And what that means is they're going to arrive most likely in Italy, specifically an island called Lampedusa.

Speaker 2 If you look at a map, you'll see that Lampedusa is actually closer to mainland Libya than it is to mainland Italy. That makes it a relatively quick journey by boat.

Speaker 2 But the big reason why many migrants choose Libya as a launching point is that Libya is a failed state. Since Qaddafi was toppled in 2011, Libya has become a realm run by various militias.

Speaker 2 And that lack of a functioning central government and the sort of general lawlessness has been a boon for human traffickers who get people across the Mediterranean for a fee.

Speaker 2 The boats they use are small, underpowered, often overcrowded, and the sea can be rough. Boats capsize, people fall off.

Speaker 2 Reports say that more than 2,250 migrants died while trying to cross the Mediterranean in 2023.

Speaker 2 And because this route is so heavily used by traffickers, the EU and Italy have put a lot of resources into making sure these migrant vessels never make it out of Libyan waters.

Speaker 2 The trip from Libya to Italy costs the equivalent of about a thousand euros. That boat trip is where Mohamed David and Aliu first met.

Speaker 2 They were with about 130 other migrants. They launched from a beach roughly 50 kilometers west of Tripoli in a city called Zawiya.

Speaker 2

The migrants weren't carrying much. You know, they had maybe a small baguette, some juice, and a couple of personal effects like a change of clothes or a copy of a Koran.

Around 10 p.m.

Speaker 2 on February 3rd, 2021, they climbed into a small rubber boat and pushed off.

Speaker 2 One thing to understand about these crossings is that the trafficker's boat isn't always intended to make the entire trip.

Speaker 2 The idea is that the trafficker gets the migrants out into the Mediterranean and then calls for help.

Speaker 2 Ideally, a bigger, more powerful ship, maybe one belonging to an NGO or maybe a merchant vessel, will respond and take the migrants the rest of the way.

Speaker 2 But it's that first part of the journey, the trip from Libyan soil to international waters, that's the most dangerous part.

Speaker 2 There are three main people that are kind of the bosses on the boat that are working on behalf of the traffickers.

Speaker 2 One is handling the satellite phone and is controlling the motor and thus the direction of the boat.

Speaker 2 That person is supposed to call alarm phone, which is this NGO that helps to try to get people rescued on the Mediterranean.

Speaker 2 and that guy is supposed to call an arm phone at a specific moment, you know, when they get far enough from shore.

Speaker 2 Second guy is supposed to sort of man this plug. You know, if you pull that plug, the boat deflates, and someone needs to stay on top of that because everyone's lives at stake.

Speaker 2 And the third guy is meant to understand the route and keep control of the people on board.

Speaker 2 So, Muhammad David was sitting next to Aliyu

Speaker 2 and

Speaker 2 he recounts how when they called Alarm Phone, Alarm Phone asked them a couple of key questions. How many people are in the boat? 130.

Speaker 2 How big is your boat? 11 meters.

Speaker 2 And alarm phone then tells the migrants that there's a merchant vessel near and they need to head towards it because the merchant vessel under international law is obligated to rescue them.

Speaker 2 So indeed the migrants do just that.

Speaker 2 But as the migrants get near the boat, Muhammad David says, number one, this merchant vessel is huge, so it's producing a sizable outflow, a wake around it, and it's causing all sorts of water to come in.

Speaker 2 the migrant raft. But number two, the merchant vessel radios down to the migrants and says, we can't rescue you.

Speaker 2 And they say, Because they don't have zodiacs, they don't have lifeboats to use to help get the migrants up onto the merchant vessel. Whether that's true or not is unknown.

Speaker 2 These merchant vessels are legally obligated to have lifeboats, so if they don't have it, they're breaking a different law.

Speaker 2 But nonetheless, the merchant vessel turns away, and the migrant boat in desperation, Mohammed David, describes as they sort of try to chase the merchant vessel, taking on more of its wake, more water into the migrant boat, which is causing an even greater sense of panic.

Speaker 2 And the merchant vessel is much faster and it leaves.

Speaker 2 The waves pick up, the water gets pretty choppy, everyone starts getting sick. And so the bottom of the boat fills with this fetid liquid that's a combination of vomit and pea and

Speaker 2 petrol and baguette crumbs and wrappers. And it's just this toxic mix.

Speaker 2 And the petrol in particular is relevant because a lot of these migrants don't realize that by sitting in water that's mixed with gasoline, you slowly are burnt without realizing it and you start peeling away skin.

Speaker 2 And so a lot of migrants have third-degree burns without knowing it when they do get rescued because they've been sitting in that water.

Speaker 2 Tensions get high, people are sick, no one is supposed to go and try to defecate or urinate over the side of the boat because that's how people fall over, so they're doing it in the boat.

Speaker 2 A fight breaks out, guy pulls a knife, threatens to take the whole boat down, he's wrestled down,

Speaker 2 everyone is afraid.

Speaker 2

Around 5 p.m. the next day, the migrants noticed a plane overhead.

They were about 20 hours into their journey and pretty far out into the Mediterranean.

Speaker 2 So plane traffic isn't something you typically see.

Speaker 2 What air traffic anyone might see out this far over the water are planes that either belong to NGOs or planes that belong to the European Union.

Speaker 2

So let me explain this a bit. So on the one side, you have NGOs, groups like SeaWatch.

SeaWatch operate a single plane. that's called Seabird.

Speaker 2 Their job is to spot migrants and coordinate rescue attempts. The other types of aircraft out there are those that belong to the government.

Speaker 2 Mostly, these are aircraft and drones operated by Frontex, which is the European Border Patrol Agency. And that agency operates a huge fleet of aircraft,

Speaker 2 pretty much 24-7 patrols over the water.

Speaker 2 When those drones and government-run planes spot migrants, they call in the information of the location to coastal states like Italy and Malta, and those countries then report that information to the Libyans.

Speaker 2 The Libyans then go and capture the migrants. So the flow of information is totally different.

Speaker 2 One set of information from the NGOs goes towards rescuing them and bringing them to safety.

Speaker 2 The other information from the far better resource 24-7 patrols, mostly by drones, goes towards Italy and Malta, which then hands it over to Libyans who capture, arrest, and bring the migrants back to a place not of safety, namely Libya.

Speaker 2 Frontext also has a clear policy of not alerting NGOs in the area that would attempt to coordinate a rescue. Again, the strategy here is not about getting migrants to safety.

Speaker 2 It's about making sure sure they never reach European waters.

Speaker 2 So the migrants in Aliu's boat saw something overhead.

Speaker 2 It circled for about 10 minutes and then left. Three hours later, they spotted a ship approaching quickly.

Speaker 2 Mohammed David told us that as soon as this new ship got close enough, they could see that it was flying a Libyan flag. People started to panic.

Speaker 2 Clearly, the Libyan Coast Guard had been tipped off and sent a boat out to intercept the migrants.

Speaker 2 During the time Aliu and Mohammed David were at sea, at least 30 emails were exchanged between Frontex and the Libyan Coast Guard.

Speaker 2 Now, what the substance of the emails was and whether they were talking about the specific vessel that he was in, we don't know. because the Europeans won't release those documents to us.

Speaker 2 But we do know that as Aliu was attempting this voyage, there was a massive amount of of communication happening between the Libyans and the Europeans.

Speaker 2 The official narrative from the EU and Libya is that this is a rescue. So the Libyan Coast Guard is rescuing these people, preventing them from being trafficked, preventing them from drowning.

Speaker 2 Now let's look at the events.

Speaker 2 This Coast Guard cutter pulls up. It first, over the loudspeaker, instructs Aliu's boat that they have to stop.

Speaker 2 They're in international waters, they don't have the legal authority to do that, but nonetheless they do. And they tell these folks they have to stop.

Speaker 2

Aliu's boat doesn't stop. The Coast Guard cutter then proceeds to ram the raft three times.

This is a large boat ramming a tiny raft.

Speaker 2

Finally, the migrant raft stops. Then the migrants are told to climb aboard the Libyan Coast Guard vessel.

And, you know, obviously they're being told by men with guns pointing at them.

Speaker 2 As the migrants climb aboard, the migrants are hit with rifle butts and whipped with hoses and ropes and told to kneel down in the center of the Coast Guard boat.

Speaker 2 You know, for any rational viewer, that's not a rescue. That's an arrest.

Speaker 2 The vessel that ends up engaging with Aliu's raft is a P-350 cutter.

Speaker 2 This is relevant because it's the very same type of vessel that the EU had made a big show of donating to the Libyan Coast Guard, the purpose being to facilitate these so-called rescues.

Speaker 2 And it just shows, again, the sort of hand-in-glove relationship between the brutality on the water and EU policy.

Speaker 2 You know, at this point in their voyage, the migrants are over 70 miles from the coast of Libya, which means they're officially out of Libyan waters.

Speaker 2 They're officially in international waters, which means the migrants don't have any obligation to listen to the Libyans.

Speaker 2 And the Libyans don't actually have any real jurisdiction to force the migrants to do anything except that they have guns.

Speaker 2 So the Libyan Coast Guard carries the migrants back to port, in this case the port of Tripoli.

Speaker 2 And when they arrive to port, the Libyan officials and UN officials who count and tally and take some basic information about the migrants are doing so using tablets donated by the EU.

Speaker 2 The migrants are then loaded into buses for transport from the port to the prisons. These buses are purchased and donated by the EU.

Speaker 2 When they get to the detention facilities, they're given bottled water donated by the EU.

Speaker 2 This matters because so often the EU says that it has no role

Speaker 2 in the infrastructure of detention, in the brutality of what's happening to these migrants.

Speaker 2 But if you actually look at each step of this process from their capture, who gave the boats, who gave the intel as to where they are, who gave the petrol to run those boats,

Speaker 2 who bought the tablets to count them up, who bought the buses to transfer them to the prison, and on and on and on. All that is EU.

Speaker 2 So this is where you start seeing the lie in the claim that the EU has no culpability.

Speaker 2 I spoke with Saleh Margani, the Libyan justice minister from 2012 through 2014,

Speaker 2 and this is what he said to me.

Speaker 2 The Europeans like to cast themselves as the saviors and their narrative

Speaker 2 and that of the Western press is often at least in subtext that the Libyans are savages and they're doing awful things in the stateless place called Tripoli to these migrants.

Speaker 2 And what the Libyans will tell you is: wait a minute, first of all, we wouldn't be engaged in this kind of migration control if it weren't for the Europeans.

Speaker 2 So the Europeans are being dishonest and trying to act like this isn't all their orchestrated and funded and equipped mission. And secondly, they are not engaged in a humanitarian mission.

Speaker 2 They, the Europeans, are engaged in a migration control mission. They don't want these people in their country, and they're paying us to do their dirty work.

Speaker 2

Look, there's some truth in what they're saying, at least to my ears. The amount of arrivals in Europe and in Italy has decreased drastically.

And the amount of departures has not.

Speaker 2

Those numbers continue to go up. And that's hugely because of the work of the Libyan Coast Guard.

So that's success if all you care about is the mission of migration control.

Speaker 2 If you actually believe the humanitarian rhetoric and that you're worried about the migrants themselves, then this has been a policy disaster because where those people that are getting captured are ending up is in a place worse than hell.

Speaker 2 And the extortion rates, the murder rates, the abuse rates, and the sheer number of bodies in those facilities has gone through the roof because of all the captures.

Speaker 2 After Mohammed David and Aliu Khande's boat was intercepted by the Libyan Coast Guard, they were forced onto the Libyan vessel at gunpoint, brought back to Libyan soil, and bussed to the secret migrant prison called Al-Mabani.

Speaker 2 Under Libyan law, foreigners can be detained indefinitely with no access to lawyers.

Speaker 2 In northern Libya, in particular, there are roughly 15 official detention centers and maybe a half dozen unofficial ones where tens of thousands of migrants have been held.

Speaker 2 Out of all the detention centers operating in 2021, Al-Mabani had a reputation for being the most brutal.

Speaker 2 It's one of the last places on earth you'd want to end up.

Speaker 2 Aliu was brought back to Al-Mabani and placed in cell block 4. The walls of the cell were covered with graffiti, things like, soldier today, soldier tomorrow, soldier for life.

Speaker 2

A soldier never retreats. With our eyes closed we advance.

God only knows our victory. You know, they were encouraging each other to soldier on.

They saw this as a fight for a better life.

Speaker 2 But I think the soldier metaphor, the war metaphor, also says something about the stakes for these people.

Speaker 2 how migrants see this as not just a choice they've made, not just sort of a hope that they'll succeed, but a matter of life and death. If they fail, they'll most likely die.

Speaker 5 Kathleen Folbig was known as Australia's worst female serial killer.

Speaker 5 She was convicted of killing her four infant children until a scientist uncovered the truth.

Speaker 5 Scientists want to know the truth and want to get to the bottom of things, particularly in a case like this where science can solve it.

Speaker 5 The Lab Detective is a story of a shocking miscarriage of justice and an investigation into why Kathleen's story might not be the last. Listen wherever you get your podcasts.

Speaker 2 Aliu managed to sneak a cell phone inside the prison in the waistband of his pants. He used it to send his brothers, Hakaria and Denbas, a voice message from inside his cell.

Speaker 2 Alio tells them that he made it through Tunisia to Libya, but was caught trying to cross to Italy.

Speaker 2 He asks his brothers to call their father in Guinea-Bissau and to let him know that he's been taken prisoner.

Speaker 2 So officially, there's a federal government in Libya, but in reality, the federal government consists of warring militias.

Speaker 2 Just within the city of Tripoli, there are different militias that control different neighborhoods and different federal agencies. And migrant detention is the spine of militia control and finances.

Speaker 2 All the detention centers are run by militias and it's a booming business.

Speaker 2 So I think it's important to understand the business model of these migrant detention centers like Al-Mabani and how the migrants are used for profit by the Libyan militias that control them.

Speaker 2 On the simplest level, the migrants are extorted. The fastest way out of one of these places is to simply buy your way out.

Speaker 2 And so the beatings and the food deprivation and the captivity and the crushing their sense of hope is all for the purpose of getting them to become more and more desperate so that when a guard comes by and offers them access to a cell phone to call their loved ones, they're that much more aggressive in trying to get someone to send the requisite $200 or whatever it is to get released.

Speaker 2 Another way the migrants get used by the militias is as forced labor.

Speaker 2 This could be as part of a legally sanctioned system where businesses and individuals are allowed to essentially rent the migrants for use on farms, in factories, or wherever.

Speaker 2 This is old-style slavery and the Libyan militias profit significantly from it.

Speaker 2 Migrants are also sent in groups to aid militias in their war efforts.

Speaker 2 So there are cases where migrants are taken out of detention centers and moved to frontline battle posts where they work on fixing military vehicles, stacking artillery, whatever job is needed.

Speaker 2 One of the major consequences of Libya's lack of a functioning centralized government is there's basically no accountability for these detention centers.

Speaker 2 Because these are militia-run, there's no ability to actually engage with the people that operate the facilities.

Speaker 2 These places are operated in darkness and secrecy, and as a result, they're especially inhumane and brutal. And Al-Mabani had a reputation for being the worst of all.

Speaker 2 Al-Mabani was a former cement depot where a Libyan militia stored building supplies until it was converted into a migrant detention center.

Speaker 2 The militia spent a fair amount of time converting it.

Speaker 2 It's roughly a square city block that had been turned into a fully functioning prison with high walls and guard towers and men walking around and camouflaged armed with semi-automatic weapons.

Speaker 2 Inside the walls, there were about eight different huge holding cells, each with the capacity to house about 200 or 300 migrants at any given time.

Speaker 2 Aliu was in cell block four. He was cramped in there with about 200 other people.

Speaker 2 There were so many people in that cell that there was barely any place to walk.

Speaker 2 In the corner of the cells, there were these buckets, and that was where, when the bathrooms were too crowded or things were clogged or whatever, people used the buckets to defecate.

Speaker 2 So the cells were horrific in terms of how they smelled, and they were also beastly hot.

Speaker 2 Overhead, there was this hum of fluorescent lights, and in the rafters on the roof, there were birds that were nested there.

Speaker 2 And so occasionally, there were bird droppings and feathers that would sort of cascade down over the migrants.

Speaker 2 It's a tense place, hot, sweaty, not a lot of food, people sick, scared.

Speaker 2 And layer onto that, you have all the sorts of tensions that you can imagine to exist on the outside world are only intensified inside.

Speaker 2 So you have a dozen different countries all crammed in there together.

Speaker 2 And so you had, you know, different religions, different tribes, different ethnicities, different nationalities clustered in a place where fuses were quite short. So fights were common.

Speaker 2 Muhammad David was held with Aliyu in al-Mabani's cell block 4.

Speaker 2 He told us how migrants who made trouble inside the prison could be held for days in an abandoned gas station that had been converted into an isolation room.

Speaker 2

The isolation room was pitch black for most of the day. It had no bathroom, so prisoners had to defecate in a corner.

The smell was so bad that the guards wore masks when they visited.

Speaker 2 Mohamed David told us that he was taken to the isolation room after he organized a hunger strike to protest how the migrants were being treated.

Speaker 2 When asked what happened to him inside, he said, quote, a lot of atrocities, a lot of wickedness.

Speaker 2 He told us the guards had strung him up upside down and beat him.

Speaker 2 In the course of our investigation, we spoke to dozens of migrants, many of whom had been held inside Almabani. They told us how they were beaten by the guards for almost any reason.

Speaker 2 Men, women, children would be brutalized for things like whispering to one another, speaking in their native tongues, or even laughing.

Speaker 2 Women were especially vulnerable inside Almabani, and several migrants we spoke to described seeing sexual abuse. Female detainees would be taken from their cells to be raped by guards.

Speaker 2 I went to Tripoli with Pierre Qatar, an editor named Joe Sexton, and another filmmaker named Maya Doles.

Speaker 2 We were supposed to be given a tour of Almabani, and we'd actually gotten that commitment in writing. But instead, we got, you know, the runaround for three straight days.

Speaker 2 And at that point, we sat down and said, look, it's pretty obvious we're not getting into Almabani, so what might we be able to do instead to get visuals of this brutal, invisible place?

Speaker 2 Because visuals really move the heart, it moves the public. It's what you need to produce to really show the true existence of something in journalism.

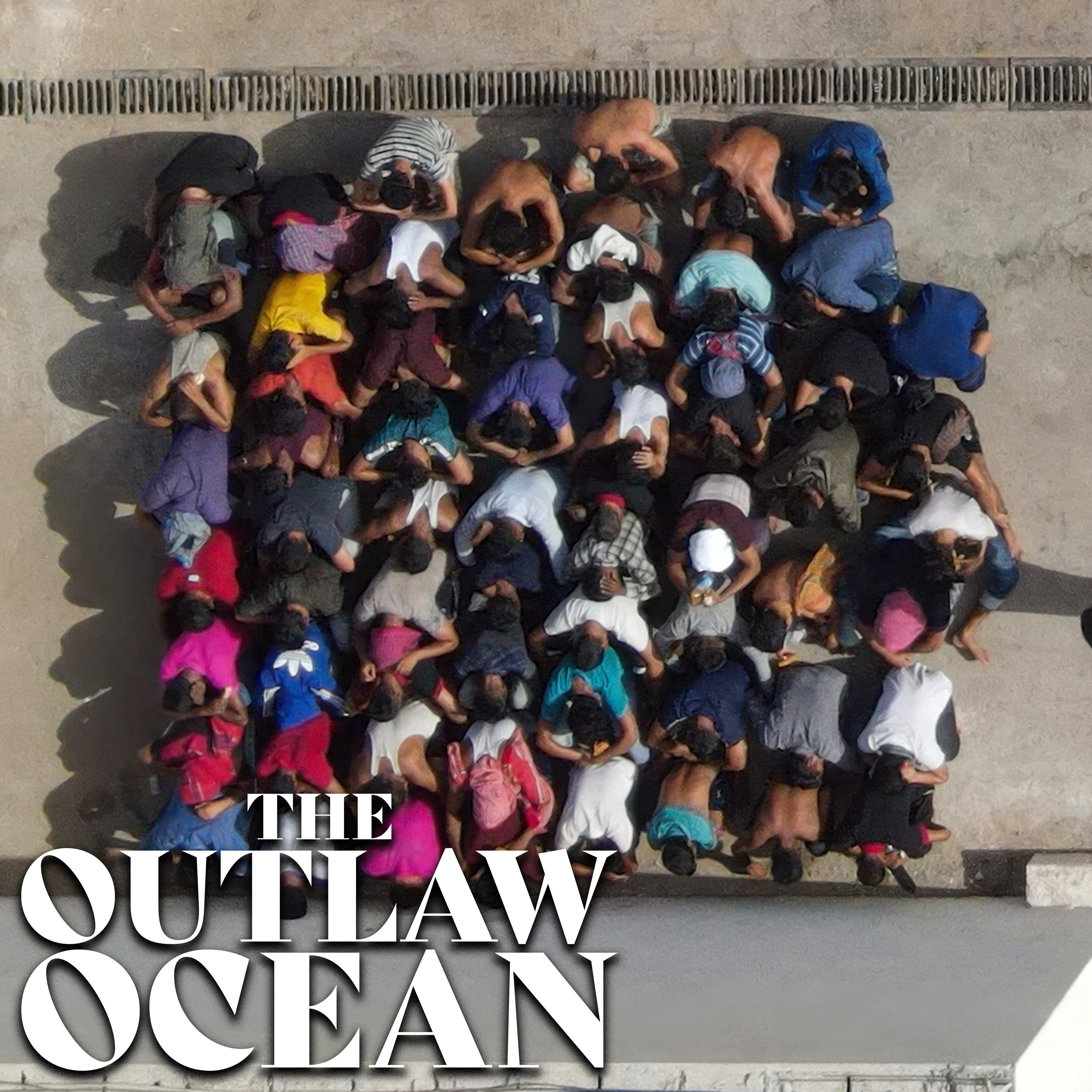

Speaker 2 So, we found this surreptitious way to get close enough to Almabani that we could launch a drone for the purposes of filming the facility and launch the drone really quickly, straight up into the air.

Speaker 2 We needed to get it high enough that no one could see it and then we traveled about you know a quarter mile away so that we got directly above Almabani but we stayed pretty high again so that the guards wouldn't see or hear it.

Speaker 2 Slowly, we then brought the drone down in altitude closer and closer.

Speaker 2 It was around lunchtime at Almabani, so there was a lot of activity going on in the open air in the central courtyard of the facility. There were maybe 50 to 100 migrants all bunched together.

Speaker 2 They were kneeling on the ground. They were supposed to stay down and forward with their foreheads tight on the back of the person kneeling in front of them.

Speaker 2 At one point, we had the drone close enough over the crowd that we could actually see exactly what was going on. And we saw one prisoner look to the side, and a guard came over right away.

Speaker 2 And the guard reached in a couple of rows over a few other guys, and he began beating this migrant for having looked to the side, hitting him with some sort of object, a hose or something.

Speaker 2 The prisoner obviously put his head back where it was supposed to be. After a few more minutes, sitting like this, the guards marched everyone back inside.

Speaker 2 when the shooting happened does he know roughly how long he had been in al-Mabani comien

Speaker 2 al-Mabani

Speaker 2 mois diminishing

Speaker 2 two and a half months

Speaker 2 that's Martin Luther he came to us through Muhammad David the two of them are friends and spent time together in Al Al-Mabani.

Speaker 2 Mohammed David had told us that Martin Luther had kept a detailed journal of his time inside the prison. So we were eager to talk to him.

Speaker 2 One of the few things that aid organizations like Doctors Without Borders can do inside these prisons is make sure migrants have access to basic needs like soap and toothbrushes and things like that.

Speaker 2 So sometimes they also provide pens and notebooks. That's where Martin Luther got his from.

Speaker 2 Martin Luther told us that he was inspired to start writing after witnessing a particularly violent incident inside Al Mabani.

Speaker 2 Some prisoners had tried to escape, and the guards responded by barricading the doors and randomly beating everyone inside the cell block. It didn't matter if they had tried to escape or not.

Speaker 2 Martin Luther had been in Al Al-Mabani longer than anyone else we spoke to, and he was able to give us some pretty incredible insight into what daily life was like inside the facility.

Speaker 2 You know, the migrants didn't know any of the guards' names, so they would refer to the guards by the orders they barked at them in the cells.

Speaker 2 So there's one guard they called Hamsa Hamsa, which apparently is Arabic for 5-5.

Speaker 2 It's It's what that guard would yell at the migrants during mealtime to remind them that it was five men to one bowl of food.

Speaker 2 Another guard was called Gamis. That means sit down.

Speaker 2

Another guard would yell, keep quiet in English. So that's what they called him.

That was his nickname from then forward.

Speaker 2 If you think about those nicknames, it just gives gives you sort of a window on what survival and existence was like for these migrants and how fearful they must have been of the guards.

Speaker 2 There were some trees and they would cut down the trees to use the wood to beat people.

Speaker 2 They also used pipes for gas pipes. Basically whatever they could find, they would use to beat people.

Speaker 2 All the migrants we talked to describe brutal treatment inside Al Mabani, Martin Luther included.

Speaker 2 But the guards used psychological violence just as frequently. One of the worst examples was this rumor that guards circulated that all the migrants would be released to celebrate Ramadan.

Speaker 2 That rumor gave Aliyu and all the other prisoners in cell block 4, most of whom were devout Muslims, a deep sense of hope, and they all clung to it.

Speaker 2 If you think about that, I think it tells you a few things. One, when you're desperate, you'll believe anything, and Aliu is desperate.

Speaker 2 So from an outside view, of course, the guards are not going to respect the religious tradition of Ramadan and let the migrants go.

Speaker 2 When you're inside a prison, you cling to whatever you can, and that's just what Aliu did.

Speaker 2 I think it also speaks to some of the sinister psychological brutality of what these guards were doing to these people, giving them a false hope on something that they hold deep, you know, their religious conviction.

Speaker 2 In any case, you know, after a couple weeks, the rumor was dispelled and hope lost, and the only option that remained for Aliu or anyone else to get out was the standard option, which is pay up.

Speaker 2 What you're hearing here is a voice message that Aliu Kande sent his family from inside Al Mabani.

Speaker 2 He lets his brothers know that someone from inside the prison will be contacting them. Aliu's hope was that his family could pull enough money to pay the ransom and have him released.

Speaker 2 One of the other prisoners inside cell block 4 was a guy named Suma. Suma had ingratiated himself to the guards and earned some extra privileges.

Speaker 2 He had access to a phone, so he was the guy you spoke to if you wanted to arrange a ransom payment. Suma would call your family and tell them what they needed to do to get you out.

Speaker 2 On April 7th, 2021, Aliu Khande arranged for Suma to call his two brothers. Aliu believed he would soon be free.

Speaker 2 Before he went to bed that night, he found his friend, Mohammed David. Mohammed David told us what happened next.

Speaker 2 Around 2 a.m.,

Speaker 2 Aliu woke up to a loud noise.

Speaker 2 Several Sudanese detainees were trying to escape. They were in cell block 4 with him, and they were trying to pry open the door.

Speaker 2

Mohammed David woke up and approached the Sudanese and said, don't do it. You know, it's a terrible idea.

It's never worked before. We've just gotten beaten.

Speaker 2 But the Sudanese were resolute.

Speaker 2 They were going to go through with it. And so they just kept working on the door.

Speaker 2 The guards saw what was happening, tried to get in front of it by backing a sand truck up against the door.

Speaker 2 That way, even if the migrants pried the door off, this huge truck would be blocking their way out.

Speaker 2 Once the guards backed the truck up against the door, the migrants realized they weren't going to be able to escape and the rage turned inward.

Speaker 2 There was a split. On one side, there were the Sudanese and others who wanted to escape.

Speaker 2 On the other side, there was Mohammed David and Aliu and some others who thought it was a really bad idea to even try. A fight broke out in the cell, and pretty soon it turned into a full-on melee.

Speaker 2

Oh my god. So basically, when the fight broke out, it was like 100 against 100.

The Sudanese guys went into the bathroom.

Speaker 2 They began pulling rebar out of the walls, you know, metal poles to use in their fight. And they began hitting other migrants in the head with it.

Speaker 2 Other migrants were grabbing chunks of cement and bottles of shampoo and anything else they could use as projectiles and they were throwing it at each other.

Speaker 2

There were fist fights happening over here and over there. They were pleading with them saying, help us, guys.

We need something to to fight with these guys. Help us, take us out of here.

Speaker 2 The brawl lasted roughly three and a half hours, and the guards mostly sat outside egging it on. At one point, one of the guards even told the migrants: If you can kill each other, go for it.

Speaker 2

In the middle of this, Ali said, I'm not going to fight. I'm the hope of my entire family.

I need to sit out.

Speaker 2 And he hid in the shower to try to bide his time and hope that things might calm down.

Speaker 2 At roughly 5:30 a.m., the guards left and came back with semi-automatic rifles.

Speaker 2 And then they started hearing, they kept fighting. And then they heard footsteps on the roof.

Speaker 2 And without warning, for no real clear reason, they began firing into the cell through the bathroom window.

Speaker 2

And all the shots were coming out of you through there. And for ten minutes, they strafed the room.

You know, Muhammad David said it sounded like a battlefield.

Speaker 2 Two teenagers, both of them from Guinea Conakry, were hit in their legs. Aliu was hit in the neck.

Speaker 2 He was trying to hide in the shower, but when he was hit, he came staggering out, blood streaming down him, and he fell to the ground.

Speaker 2 How many days between

Speaker 2 his boat getting captured and the shooting? How many days were there?

Speaker 2 Two months?

Speaker 2 Four days? Four days.

Speaker 2 Aliu Khande was shot and killed on April 8th, 2021. Mohammed David's two-month imprisonment in Al-Mabani ended the next morning.

Speaker 2 Mohammed David told us that the shooting stopped once the guards realized that they'd killed Aliu.

Speaker 2 The guards who had fired into the cell were young, and it was clear to Mohammed David, at least the other migrants, that they were panicking.

Speaker 2 They quickly offered to free everyone in cell four in exchange for Aliu's body.

Speaker 2 They said, sorry, listen, we swear to God, if you give us the body, we will let you go.

Speaker 2 They said, we swear, you give us the body, we'll let you go. The migrants barricaded themselves in the cell and told the guards that they could only have the body after everyone was freed.

Speaker 2

The stalemate continued until a guy named Nordine Al-Greeatli showed up. He's the militia commander who was in charge of Al-Mabani.

Their boss came and said, I want to see the bodies.

Speaker 2 Greetley looked into the cell. He saw the blood filling the plastic sheet that covered Aliu's body, and he went ballistic.

Speaker 2 The guy said, we can do everything to these guys. We can torture them, but not kill them.

Speaker 2 He said this.

Speaker 2 Muhammad David and the other prisoners demanded that Greatley call one of the NGOs that monitored Al-Mabani. So the International Organization for Migration or Doctors Without Borders.

Speaker 2 Greetley said that the NGOs couldn't do anything. He told them, we are the police, we are the law.

Speaker 2 He said, I promise.

Speaker 2 I promise in front of God.

Speaker 2 That you guys will leave today, you'll be free today, but let me talk to you.

Speaker 2 As the stalemate between Greeley and the prisoners inside cell block 4 continued, Greatley called in Suma to help negotiate.

Speaker 2 He's the prisoner I mentioned earlier who facilitated ransom calls and was friendly with the guards inside Almabani.

Speaker 2 Suffice it to say, Suma was not well liked by the other prisoners.

Speaker 2 So

Speaker 2

when he came back, he said, guys, I know you don't trust me. I know you think I'm on their side, but I'm telling you, today you're going to be free.

But I want you to be able to do that.

Speaker 2 Suma promised the other migrants that if they walked out calmly without causing more chaos, they'd be allowed to leave Almabani safely.

Speaker 2 So then they all go running out. They walk or run or run.

Speaker 2 Run. Yes.

Speaker 2 Everyone? Yes.

Speaker 2 And this was what time of day? I can't remember.

Speaker 2 And then when did everyone disperse? And were people in the middle of the day?

Speaker 2 Everyone just dispersed. Yes.

Speaker 2 And people ran from here all the way, or they walk here and then they start running.

Speaker 2 Run.

Speaker 2 Like ta-jogging.

Speaker 2 Sprinting.

Speaker 2 All men. All men.

Speaker 2 And there would have been people seeing on the street traffic at 9 a.m., right?

Speaker 2 Ali's life ended in cell block 4.

Speaker 2 He was never able to fulfill his dream of improving his family's fortunes, of providing a better life for his wife, his children, his parents.

Speaker 2 To the EU, Aliu was a threat, a symbol of what is to come as more and more migrants make the same decision to seek a better life in Europe.

Speaker 2 To the Libyans, Aliu was a thing to be exploited, a way to make money through extortion or slave labor.

Speaker 2 And in the end, for his fellow prisoners inside Almabani, Aliu was kind of a way out.

Speaker 2 My team had been in Tripoli for about a week, looking into Aliu's death and trying to learn more about the network of migrant prisons like Almabani.

Speaker 2 We'd made some pretty good headway on the story despite the roadblocks we'd encountered from the Libyan government.

Speaker 2 The bulk of our reporting was wrapped up and we were all looking forward to getting out of the country.

Speaker 2 It was a Sunday night and the rest of the team decided to leave our hotel with the security detail and head to a nearby restaurant for dinner.

Speaker 2 I had some work to finish and I wanted to call my family, so I decided to hang back.

Speaker 2

I was on the phone with my wife when I heard a knock at the door. I walked over to the door, phone in hand, and opened it.

Standing there were a dozen armed men in military uniforms.

Speaker 2 They started screaming at me in a mix of Arabic and English, and then pushed me backwards as they forced their way into the room. They put a gun to my head and ordered me to the ground.

Speaker 2 I remember feeling the cold metal on my forehead, and that I was moving very slowly and very deliberately because I was afraid they were going to shoot me.

Speaker 2 I had no idea what was going to happen next, but whatever was coming, I knew it wouldn't be good.

Speaker 2

This series is created and produced by the Outlaw Ocean Project. It's reported and hosted by me, Ian Urbina, written and produced by Michael Catano.

Our associate producer is Craig Ferguson.

Speaker 2 Mix sound design and original music by Alex Edkins and Graham Walsh, additional sound recording by Tony Fowler. For CBC podcasts, our coordinating producers Fabiola Carletti,

Speaker 2 senior producer Damon Fairless.

Speaker 2 The executive producers are Cecil Fernandez and Chris Oak.

Speaker 2

Tanya Springer is the senior manager, and R. F.

Narani is the director of CBC Podcasts.

Speaker 2 Special thanks to Pierre Katar, Joe Sexton, and Maya Doltz.

Speaker 2 For more CBC podcasts, go to cbc.ca slash podcasts.