BONUS: Y2K feat. Colette Shade

Purchase “Y2K: How the 2000s Became Everything”:

Bookshop: https://bookshop.org/p/books/y2k-how-the-2000s-became-everything-essays-on-a-future-that-never-was-colette-shade/21416954?ean=9780063333949

Audible: https://www.audible.com/pd/Y2K-Audiobook/B0D3G5JV6P

Catch Colette on here book tour, dates here: https://www.coletteshade.com/

Press play and read along

Transcript

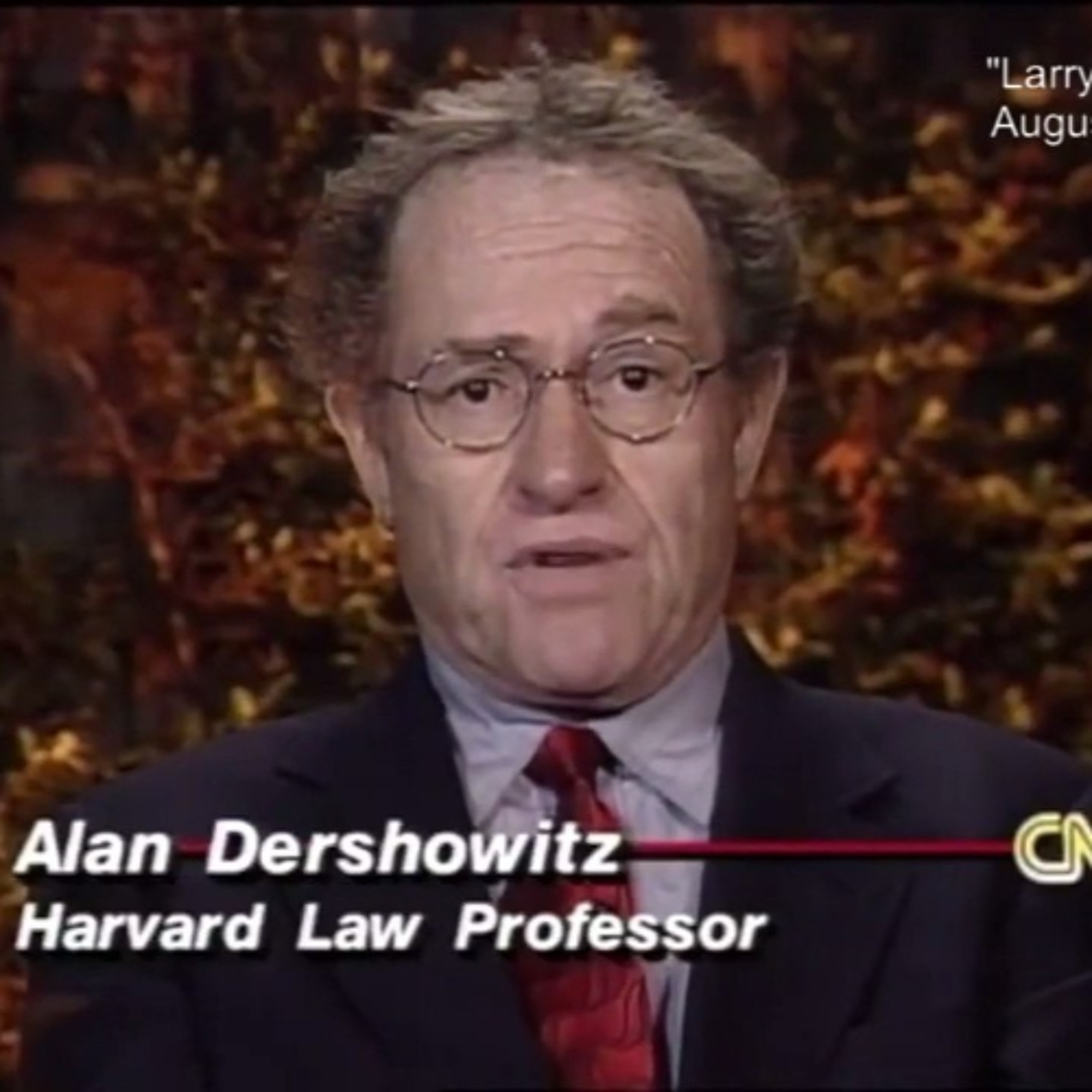

Speaker 1

Greetings, everybody. We've got some bonus shoppo coming for you today.

It's me, Will, here today.

Speaker 1 And on this episode, I will be talking to the author and critic Colette Shade about her new book, Y2K, a collection of essays that

Speaker 1 examines the phenomenon of millennial nostalgia for the late 90s and early 2000s as a kind of

Speaker 1 an examining some of the fissures that

Speaker 1 sort of the

Speaker 1 crevices and sort of a darkness that undergirded an era that is mostly remembered now as an area of stupid, good times, good vibes, and endless fun and hope for the future.

Speaker 1 Colette, welcome to the show.

Speaker 2 Hey, Will, thanks for having me. I haven't been on the pod since I was writing that Pacific Standard piece in 2016.

Speaker 1 Well, there you go. Yeah, that's a little payola, you know,

Speaker 1 write a piece about Ciapo in 2016, and we'll have you on to talk about your book in 2025.

Speaker 2 Yeah, well, thanks for that.

Speaker 1 It's been a long time coming, Colette. So yeah, your book, Y2K,

Speaker 1 I really enjoyed it

Speaker 1 as an elder millennial myself.

Speaker 1 The years and era you're talking about is an era that encompasses, like, you know, I'm a little bit older than you, but it's an era that encompasses high school, college, and then like what should have been adulthood for me, but then like the sort of delayed or permanent recession of adulthood in the millennial generation is sort of a theme of this book.

Speaker 1 But I want to begin by,

Speaker 1 you talk about the Y2K era in American culture. And like, I mean, and as we talk about it, like, you know, the features of that era, I think, will slot into people's minds pretty easily.

Speaker 1 But, like, what is the actual time period we're talking about here?

Speaker 1 What years encompass the Y2K era as you perceive it?

Speaker 2 Yeah, so the years that I pick for the purpose of scope for this book are 1997 through 2008. So that is the kind of burgeoning growth of the dot-com bubble.

Speaker 2 Technically the dot-com bubble started in 1995, but I picked 97 because that's when I feel that the excitement and optimism of the dot-com bubble started to inform fashion and popular culture.

Speaker 2 And then the book ends in 2008 with the spectacular meltdown of the entire global economy.

Speaker 1 So yeah, it begins with an era that was sort of created out of the optimism of both

Speaker 1 the rise of the internet and the real like coming to the fore of like the computer as probably the most society changing innovation in human culture since the atom bomb, but also a kind of end of history moment for the world, like

Speaker 1 the post-collapse of the Soviet Union and the kind of instantiation of like a global democratic liberal hegemony in the world before it all started coming apart, which is also a theme of the book.

Speaker 1 But I guess

Speaker 1 in considering this collection of essays,

Speaker 1 the first thought I had was thinking about the actual Y2K panic.

Speaker 1 This idea, for those who remember it, the idea was that on New Year's Eve, 1999 into 2000, like computers would like when it switched over from 99 to 2000 to two zeros, that that would somehow crash the entire global computing infrastructure and then like everything it would instantiate essentially a computer-based apocalypse.

Speaker 1

And I remember when that fear was happening, nobody really took it seriously. I like, it seemed dumb.

And then, like, in retrospect, it seems even dumber.

Speaker 1 However, however, Colette, I really do think that the essential mythology, the myth, the idea of Y2K has come true. Computers have destroyed the world, and the 21st century has been a horror show.

Speaker 1 What do you make about like this sort of subconscious yearning in our society or communication of the idea that like the era of endless hope and a bright future was bound to be doomed in early in the 20th 21st century.

Speaker 2 Yeah, I mean, I think that there was an awareness that this was all too good to last.

Speaker 2 So like, just for some background, the late 90s, the stock market is hitting records. We've got the Dow hitting 10,000 for the first time in its history.

Speaker 2 Rudy Giuliani, who's the mayor of New York City at the time, wore a little hat that said Dow 10,000 as he rang the closing bell in March 1999.

Speaker 2 You had an MIT economist in 1998 saying, we will never have another recession again.

Speaker 2 Another guy, George Gilder, who's kind of a conservative gadfly and policymaker, who's still around, by the way, he wrote a book, I believe it's called The Israel Gene, is his most recent hit.

Speaker 2 The Israel Gene about how I think it's basically like phrenology for why Israel is good and should keep doing what it's doing but anyway so this guy this guy basically said that the and he said this in the early 90s that the internet would allow us to finally finally overcome those pesky laws of physics that had enslaved humans for all of history and we would just be able to transcend the brute physical world and essentially have unlimited prosperity, peace, and understanding for all.

Speaker 1 Like the Y2K hysteria was was perhaps misplaced, but

Speaker 1 did accurately capture a kind of a collective unconsciousness that the good times were soon to end and that they would be ended by this combination of kind of end of history, capital hegemony, capitalist hegemony, and the internet and computing.

Speaker 1 But when you talk about like this feeling that the good times would never end, I think like one of the main parts of your book is about sort of decanting and investigating the popular culture of that era.

Speaker 1 What are some of the ways in which the sort of pop music, television, like whatever you're thinking, but like, what are some of the ways in which like the pop culture of the late 90s, right before 9-11 and the era of good vibes ended forever?

Speaker 1 How did that reflect this kind of end of history, endless optimism, and good hope?

Speaker 2 Yeah, so you've got

Speaker 2 like the fashion.

Speaker 2 Suddenly everything becomes silver, white like silver eyeshadow and nail polish was the look Maybelline had a campaign for like it was like silver makeup for the new millennium because we're all just going to be wearing silver I guess

Speaker 2 one of the things that I begged my mom for the opening essay of the book talks about how I begged my mom to buy me a silver inflatable chair from Target in 1999 because it was essentially advertised as this is the chair of the future.

Speaker 2

This is the chair of the new millennium. And I was like, my God, I don't want to get left behind.

I want to have silver furniture just like everyone else will have in the new millennium. And

Speaker 2 I mean, God, there was like body glitter, that sort of look that girls and women would wear.

Speaker 2 And then also in terms of, I think one of the places you actually see this most is in hip-hop and RB and pop videos. So like TLC had a super like multi-platinum album called Fan Mail, and the

Speaker 2 theme of the album was email, email on the internet. And there

Speaker 2 and

Speaker 2 in there's their video for no scrubs. They're wearing these silver, like futuristic, cool, sexy space suits.

Speaker 2 They're dancing around on a space station.

Speaker 2 That was 1999. A couple years before in 1997, Puff Daddy and Mace had a song called Mo Money, Mo Problems.

Speaker 2 In the video, Mace and Puff Daddy are wearing these amazing like silver like streetwear outfits, bright, shiny yellow, latex, like, white, just really cool, shiny black, like, really cool looking.

Speaker 2 They're floating around in zero.

Speaker 1 Yeah, a huge element to this video was both

Speaker 1 the bright red sort of like coveralls, these sort of like, these shiny, bright red coveralls. But it was Puffy and Mace, and they were like, they were floating in some sort of zero gravity simulator.

Speaker 1

And it's both the message of the song and the visual images of it is that like literally you're never going to come down. That like the world the world is now weightless.

It's shiny.

Speaker 1 And like the only problems that we have is that there's too much goddamn money for everyone.

Speaker 2 Yeah, there's

Speaker 2 problems that are coming from the money.

Speaker 1 The problems are coming from within the money.

Speaker 1 Yes, actually.

Speaker 1 But like, I feel like this is but one example. And I think the interesting thing is like to look back on it now, both because of the people making it in terms of Mr.

Speaker 1 Diddy himself, but also like the message,

Speaker 1 there was a real darkness undergirding all of this that seemed, that was like maybe hard to discern in the moment. But looking back on it now, what are some of the ways in which this kind of the

Speaker 1 poptimism of the late 90s and this kind of like

Speaker 1 weightless fantasy world it created?

Speaker 1 What are some of the ways in which we should have anticipated like a coming darkness or a darkness that it was communicating in perhaps an unconscious way.

Speaker 2 Well, I think the best example of this is the fact that this inflatable chair that I begged my mom for in 1999 until she finally bought it for me popped in about a month.

Speaker 1 So

Speaker 1 sitting on a balloon was not, in fact, the chair of the future?

Speaker 2 Well, it was, but not the way that I thought. It then turned into a piece of

Speaker 2 flaccid, cold plastic that wound up in the trash.

Speaker 1 Well, you know, now we live in the plastic plastic trash reality. We're still waiting for some chair innovations in the 21st century.

Speaker 1 I don't think they've come up with anything better than the old model, but hopefully Silicon Valley will come up with a new and better chair.

Speaker 1 But yeah, like you also talked about like that era when like every Mac computer had that like sort of soft bubble with the colored plastic on it.

Speaker 2 Yeah, and I write about that. One thing that I wanted and never got

Speaker 2 was the Mac G3 which was designed by Joni Ive and it was it came out in 1998 the first color was Bondi blue because get it Bondi Beach is a surf spot and you're going to use it to surf the web oh

Speaker 2 interesting yes and then the next year 1999 they came out with like I think it was like five colors it was like orange, raspberry, lime, blueberry. They're all named after fruits.

Speaker 2 So it, you know, it was keeping it light and fun and quirky. But I think the thing that really sticks out to me about this design is that you can see inside of the computer.

Speaker 2

So it's almost saying like, hey, technology is fun. It's not scary.

It's it's round. It's soft.

It's not going to hurt you with angular lines. And

Speaker 1 almost supple and breast-like and contours.

Speaker 2

It's a breast-like, yeah, yeah, kind of sexy. And yeah, and you can see what's going on.

It definitely is not spying on you. You can spy on it.

Speaker 2 It's not spying on you and just dragnetting all of your data to sell off to mysterious data brokers in the NSA.

Speaker 1 I mean, I should note that the laptop I'm recording this on now is like a black rectangle, like gunmetal box that's completely impenetrable.

Speaker 1

Exactly. Yeah.

But like

Speaker 1 in terms of like

Speaker 1 some of the some of the examples of like the pop culture of the era, when I think about about the 90s,

Speaker 1 what's interesting is that some of the most popular, some of the most long-lasting and memorable culture of that era, I think about shows like the X-Files, which sort of came out of nowhere in that it was so much different than this dominant mode of sort of like

Speaker 1 witless optimism and

Speaker 1 this frictionless reality of eternal abundance and optimism.

Speaker 1 But nonetheless, kind of similar to the way in which people needed to believe that the world was going to end because of the computers rolling over to zero. Shows like the X-Files,

Speaker 1 it captured this bone-deep suspicion that people weren't really ready to

Speaker 1 communicate consciously, but that there is a real, like I go back to this idea that there's a real darkness underneath all of this, that something is wrong. And it would not last.

Speaker 2 Yeah, and the other thing I want to say is that there were non-subconscious signs of this too, right? So I was born in 1988

Speaker 2 in an inner ring suburb of Northern Virginia.

Speaker 2 And like four days before I was born and like maybe five or six or eight miles from where I was born, James Hansen testified for the first time in the Capitol saying that climate change posed an existential threat to humanity.

Speaker 2 And so throughout the 90s, we like knew that climate change was happening and was getting worse and was going to be a big problem.

Speaker 2 But it was, of course, at the time in the Y2K era talked about as a problem of the future or a problem for quote-unquote our children's children, not like people actually living at the time.

Speaker 2 Despite when we actually look back now, we can see that some of the disasters that happened, whether that was like heat waves and floods in the 90s or like Hurricane Katrina, these were exacerbated by climate change.

Speaker 1 To return to P. Diddy and Mace, More Money, More Problems,

Speaker 1 it's such a different era of pop music, particularly in rap music. Like, the tone and look of that whole song could not be more out of place with today's rap and hip-hop music, which is like,

Speaker 1 if I had to describe it, it would mostly be like, I've taken so many pills, I can't feel anything anymore.

Speaker 1 That seems to be the dominant ethos of today.

Speaker 1 But, like, what are some other examples of, and like, the other thing that's interesting about your book is that, like, you're not, you're not criticizing the pop culture of this era.

Speaker 2 You said that you're an unabashed uh like enjoyer of this like uncritical i love all of it everything basically everything that i write about except for maybe like girls gone wild i would not say i'm a fan of that you're not a fan of that no i'm not

Speaker 1 I mean, it was all, yeah, it was just bosoms. It was just bosoms and breasts over and over again.

Speaker 2 Well, here's the thing. If it was just bosoms and breasts, I think I'd be more of a fan of it.

Speaker 1 Yeah, I was actually... Well, yeah, talk about like

Speaker 1 another stupid, awful thing from that era era that like at the time was just like, oh, here's a bit of

Speaker 1 a ribald bit of a good time. But like of what we know now about Joe Francis, this was just like

Speaker 1 pure sexual assault and exploitation.

Speaker 2 Yeah, pretty much. Yeah.

Speaker 2 Right.

Speaker 2 I mean, like there was, I talk about, there's an essay that I have about sort of sexuality and porn and purity culture and kind of comparing and contrasting different approaches to sex and sexuality during the 90s.

Speaker 2

And I think that one of the really interesting things, well, not interesting. I don't know why I said it was interesting.

It's actually horrifying.

Speaker 2 One of the horrifying things about, like, say, specifically about Girls Gone Wild is that there's been a lot of investigation about how this stuff wasn't just, you know, in some cases, sure, it was girls consensually flashing and performing for the camera.

Speaker 2 But in other cases, you know, girls have said, hey, I was too drunk to consent.

Speaker 2 You know, they ambushed me on the street of New Orleans while I was on spring break and blackout drunk and were like, hey, sign this paperwork and be on Girls Gone Wild. And I was like, sure.

Speaker 2

And then I didn't remember it. And then my face was and breasts were being used to market this thing.

And it was just terrible. Right.

Speaker 2 And, and the other thing I want to add is I think that because one of the big things that I talk about is that there was a real aversion to any kind of politics during this era, whether that was like a socialist or leftist economic politics, whether that was an anti-racist politics, and certainly feminism.

Speaker 2 Like it was an extremely anti-feminist time. And so people who raised questions about this, who were like, hey, this doesn't seem so good, were sort of seen like, oh, you're a boar.

Speaker 2 You're, you know, you're a wet blanket. Like, get out of here and shave your hairy pussy.

Speaker 1 I don't remember that part of the.

Speaker 1 Actually, you know what? I do remember that. This is when this is when Brazilians became like.

Speaker 2 Yes, this is actually when Brazilians became a thing. So it was like, if you were perceived,

Speaker 2 I definitely had someone say something like that to me at one point.

Speaker 1 Well, I mean, like, it fits in with like what you're trying to communicate about, like, the sort of the dominant communication of sexuality in this era.

Speaker 1 Like, I think about Britney Spears and Christina Aguilera and like these highly sexualized, sort of like teenage pop stars that were beginning to borrow heavily from the aesthetics of pornography, but it's this mix of purity and degradation and sleaze like mixed together.

Speaker 1 And like,

Speaker 1 what do you make of the messages of the sort of like female pop music of that era?

Speaker 2 Yeah, so actually I do want to draw a distinction because Christina Aguilera always stood out among the female pop stars because she, I don't think to my knowledge, ever was like wearing a purity ring or talking about purity.

Speaker 2 And she also sang

Speaker 2 in many ways like more explicitly and confidently about sex and sexuality like come on over, baby, is literally about like a woman who's horny and wants to have sex and the guy's not sure if he wants to have sex.

Speaker 2 And she's like, no, it's cool. It's, it'll be fun.

Speaker 1 Genie in a bottle. Got a rubber right over here.

Speaker 2

Genie in the bottle. No, exactly.

She's literally saying, she's literally saying.

Speaker 1

And then want to get dirty. Wanna get dirty.

Yes, want to get dirty.

Speaker 2

Right. Want to get dirty.

Right. Like, genie in a bottle is literally saying, like, you're bad at foreplay.

Like, here's how you can be good at it.

Speaker 1 Right.

Speaker 1 I think that's a good point. I I mean, I guess

Speaker 1 I threw Christina in there because she was like the other really huge pop star.

Speaker 1 This is more in line with Jessica Simpson. Jessica Simpson.

Speaker 1 Who advertised that she was staying pure until marriage.

Speaker 2 Yes, right.

Speaker 2 And so here's what was really strange about the marketing at this time is that female pop stars were expected to be like essentially style themselves after porn stars like Jenna Jameson, like have like the blonde hair, wear like super skimpy clothing,

Speaker 2 be just like waxed and tanned to every inch of them and sing and dance in sexualized ways.

Speaker 2 But then they were in a lot of cases also expected to present kind of a virginal, not kind of, like a literal virginal

Speaker 2 vibe, right? Like Brittany.

Speaker 2 She was, you know, she said for at least a couple years that she was staying a virgin until marriage. And this was very much a big part of her image.

Speaker 2 And there was this interview, I forget who it was with, where she said like she didn't understand why

Speaker 2 people found her dancing in a schoolgirl mini skirt to be sexual.

Speaker 2 And, right? And so it's like,

Speaker 2 what this says to me is that it's saying like, This is all for the purpose of men, right?

Speaker 2 Because if a woman is like knowingly sexual, then she's scary and then she can like, I don't know, tell you you're doing foreplay badly.

Speaker 2 But if you, if she's like essentially sexualized to be almost like a little girl right so there's like this David LaChapelle rolling stone shoe and look again I love David LaChapelle's work I think he's a great photographer and this was kind of a smart winking nod to this perhaps but like there is a picture of her riding a child's bicycle um wearing shorts that say baby There is a picture of her in bed in like satin lingerie holding a teletubby, which is a

Speaker 2

yes, no, exactly. We all do.

It's seared into our elder millennial brains. And to me, what this is communicating, and again, I was born in 1988.

Speaker 2 And so, and the book covers from when I was nine in 1997 through when I was 20 in 2008. And so, this is like right when I'm hitting puberty, like 10, 11, 12, 13.

Speaker 2 And so, the message I'm getting is, I have to be a sexy woman, but I'm not allowed to like say what I like sexually or be or sexually pursue voice.

Speaker 1 You have to present yourself in a way that's highly sexualized and informed by the aesthetics of pornography,

Speaker 1 which is, yeah, which is, thanks to the internet, has became like more, more saturated into people's brains and the culture than it ever had before.

Speaker 1 But at the same time, you have to do this while also like portraying this very childlike, we're like childlike.

Speaker 1 So it's like you you are you are sexual to be consumed by other people but you have no sexuality of your own right you have no sexuality of your own right which is like pretty creepy and give me a sign

Speaker 1 kiss me baby one more time

Speaker 3 well uh

Speaker 1 less creepy is i think i think one of the one of my favorite chapters in the books is about how you learned about sex through a ludicrous song how you learned about sex through what's your fantasy and like you know ludicrous is another another rapper of an era, like, who, whose songs were very fun, goofy.

Speaker 1

They were very, like, tongue-in-cheek. And they were about like having fun and like good times.

But, like, what was it about the song, What's Your Fantasy?

Speaker 1 Your confusion about like, you were like, you're like, I'm aware of what sex is, you know, like P and V and whatnot. But like, is everyone doing it on the 50-yard line of the Georgia dome?

Speaker 1 Like, what is this? On a library on a stack of books? How would that even work?

Speaker 2

Correct. Yes.

Yeah. So this was a big thing.

It's funny.

Speaker 2 I was talking to someone else at, I did an event at McNally Jackson a couple nights ago, and someone came up to me and was like, oh yeah, I had the exact same experience hearing that song where I was like, this is a nasty song.

Speaker 2 Like,

Speaker 2 yeah, right?

Speaker 1 Like, it's like, the funny thing is it's not, it's not really that nasty.

Speaker 1 It's actually like, if you listen to lyrics that song, they're actually like, I mean, yeah, they're, they're, they're, they're, they're dirty, but like, it's, I would never be. Disrespectful of women.

Speaker 2 It's like, it's actually like not, it's interesting because I talk about like misogyny and rap music which i can get to in a minute but this song is actually like not disrespectful of women this is like hey what are you into tell me what you're into like what's your fantasy what's your fantasy what are you into yeah what are you into um right but so so how i came into this song i was in seventh grade and one of my best friends calls me up and she's like oh my god have you heard of this song it's so nasty and she tells it to me she tells me about this and so i i turn on mtv and i'm like waiting for it to come on and then when it comes on of course, I'm shocked because I assume it, she describes the video as being nasty.

Speaker 2 And it's just like him driving around in a car and like dancing in a parking lot with some people.

Speaker 2 I thought it was going to be like porn. But he talks about like he basically lists every conceivable sexual fantasy, right?

Speaker 2

So he says like, um, we can do it with whipped cream and strawberries and cherries on top. We can do whips and chains.

We can do role playing.

Speaker 1 By the way, that's no, that's nobody's actual sexual fantasy.

Speaker 2

Right. I know.

I don't.

Speaker 1 strawberries and cream yeah yeah whipped cream i mean once again it's one of those things that like when you're a kid and like look long before you become sexually active and but you're interested in sex and you want to know what what is this whole undiscovered continent of adult life going to be like and i thought the under undiscovered continent of adult life was going to be having sex with whipped cream and in the library

Speaker 1 it's like yeah is this sex or working at baskin robbins like what is going on

Speaker 2

he does talk about food a lot. I think he says chocolate is involved at one point.

Yeah, he says chocolate, chocolate, make it melt.

Speaker 1 But

Speaker 1 another aspect of the book is like,

Speaker 1 what was your introduction to the internet and like, and then like the attendant social realities of sex and like adult life as like, you know, as teenagers.

Speaker 1 as the generation that sort of became teenagers as the internet blossomed into what it is today.

Speaker 2 Like, what was your first experience with the internet yeah so the internet first came to my house in 1995

Speaker 2 meaning like again what I think is important to note about the millennial cohort is that we basically all remember getting the internet for the first time which

Speaker 2 as children basically and I think that that's very very interesting because like for older cohorts you know this occurred this change occurred as they were adults For younger cohorts, they were just born into it, right?

Speaker 2 The internet was already in their houses and not just in their houses, but like on their phones.

Speaker 2 Right. So in 1995, my mom says, hey, do you want to go on the internet? And I go, what's the internet? And

Speaker 2 she takes me on and she's like,

Speaker 2 so we go to a search engine, you know, Yahoo.

Speaker 2 And she's like, well, what are you interested in? I was like, Xena Princess Warrior.

Speaker 2 So I type in Xena Princess Warrior and I go to some fan site and it, you know, it takes two whole minutes for a single picture to load like line by line. Oh, yeah.

Speaker 1 You know, if you're, and like, yeah, and if you're a horny teenage boy of that era, I cannot, I cannot underscore to you how, how much of like a ceiling was put on your,

Speaker 1 shall we say, youthful energies by dial-up speed.

Speaker 2 Yeah, like, The youth today do not know, do not know what that was like to have to just like watch something blink into view very slowly.

Speaker 1 I remember going to a playboy.com and like waiting five minutes for an image to render down to where the nipples were exposed.

Speaker 2 You're like, okay, go down.

Speaker 1

Line by line. I'd be like, okay, I've seen her earlobes.

This is going to get really good in about another four and a half minutes here.

Speaker 2 Yeah, no, I mean, so I specifically remember.

Speaker 2 going you know logging on and then you know it was dial up and so i think another really interesting thing is it wasn't until 2005 that wireless surpassed dial up so there was this real buffer

Speaker 2 between internet and non-internet life so you would have to actually say okay I'm logging on see if the phones are free dial up that takes like a minute 60 seconds or so you're online and then oh someone picked up the phone you're offline And it wasn't until 2005 that you had wireless where you could just open up your browser and be on.

Speaker 2 And then it wasn't until 2017 or 2017. I'm sorry, 2007 that you had iPhones where now suddenly you can

Speaker 2 be online on the toilet. That was not a possibility before.

Speaker 1 Well, unless you had a computer in your bathroom, which, you know,

Speaker 2 I'm sure some people did. But yeah, like I talk in the book about how around like 1999, AIM and chat rooms became the place to be.

Speaker 2 My screen name, Will, what was your screen name?

Speaker 1 Oh my God, this is so dorky.

Speaker 1

Oh my God. This is the worst question anyone has ever asked me.

My AOL screen name was Theseus 12 because I was a fan of Greek mythology.

Speaker 2 That's good. That's good.

Speaker 2 That actually makes a lot of sense to me.

Speaker 1 Well, I like Theseus because unlike Hercules, like he was sort of a, he was a smaller guy who survived by his wits rather than his brawn and muscle. So very fitting, very fitting.

Speaker 1

Way to get out of the labyrinth. But, you know, the labyrinth is a good, good, actually a good metaphor for the internet.

Yeah. So I guess I chose wisely.

Speaker 2

Yeah, I think you did. Yeah.

So I was a little alien too.

Speaker 1 You also wrote about your experiences of

Speaker 1 chatting. I mean, like, you know, because the internet, like, sort of previous, like, to have like our, like, like the boomer generation, like,

Speaker 1 the mass proliferation of the automobile. and like cars.

Speaker 1 That was like, if you were a teenager and you had access to a car, that was your access to social life, to sex, to a world outside your parents' authority.

Speaker 1 And I think for our generation, the internet really was that for us, creating this kind of virtual space of lawlessness, free of adult supervision. So, like,

Speaker 1 how did you take advantage of that?

Speaker 2 Yeah, so I write about, I write in

Speaker 2 the essay about sex about how in 2001, when I was in eighth grade, I was 13, I went in a chat room and I think it was like a, supposedly like a local teens chat room. And I was like, hey, I'm

Speaker 1 everyone in that chat room is a pedophile. Right.

Speaker 2 Well, I'm getting to that.

Speaker 2

Don't worry, this doesn't go anywhere too dark. But so I go in and I'm like, hey, I'm a hot 13-year-old girl.

Are there any hot 13-year-old guys?

Speaker 1 These 12 has entered the chat.

Speaker 2 Yeah.

Speaker 2 These 12 or whoever, he like private IM'd me and we're chatting and he's like, oh, what do you look like?

Speaker 2 And so I lied because I basically, but I lied in a way where it wasn't like so extreme, but I was like, oh, I have B cup breasts and I'm 5'5

Speaker 2 instead of I'm an A cup and I'm 5'1.

Speaker 2 I thought, well, maybe if we meet, maybe he just like won't notice or something.

Speaker 2 And then he is like, okay, okay cool do you want to like meet and suddenly something started to click in my head and i was like wait wait a second and then he's like where are you from and i said i was from the town that was like two towns next to the town where i was from and then i logged off

Speaker 1 lock the computer in a safe and threw it into a reservoir

Speaker 1 so that like

Speaker 1 the dividing line here between the end of the 90s and the end of history and the world that we're currently living in now is essentially two events, 9-11 and the economic collapse of 2008.

Speaker 1 First of all, Colette, I got to ask you, do you remember where you were when 9-11 happened?

Speaker 2 Yeah, I watched it live on CNN in my civics class.

Speaker 1 They wheeled the TV into the class?

Speaker 2 Well, no, no, actually, it's crazier than that. So our civics class in eighth grade was having a unit on current events and the news.

Speaker 2 So we started off every day for that unit watching CNN and we turn on the TV and you were just supposed to watch a regular CNN that morning? Yeah.

Speaker 2 And then there's smoke pouring out of the Twin Towers and everyone starts freaking out and then the TV and the entire school gets cut.

Speaker 1 That must have been frightening. Well,

Speaker 1 actually,

Speaker 1 to return to sex and pornography for a second,

Speaker 1 the one thing I learned in your book that was genuinely jaw-dropping to me was that in the famous, in the 2004 paris hilton sex tape one night in paris uh you said that uh you you write that uh the the the the the paris hilton sex tape opens with the following in memory of 9-11 2001 we will never forget yeah

Speaker 1 that's exactly

Speaker 1 that

Speaker 2 was the book

Speaker 2 like

Speaker 1 collette like i if you wanted to have like like the the poll quote the elevator pitch for this book that describes what we're talking about here it's the fact that the paris hilton sex tape opens with a 9-11 we will never forget Memorial.

Speaker 2 Yes, and it's also shot in night vision, which I know. Which is like, which is like the

Speaker 2 Iraq War basically all the time.

Speaker 1 I had never considered that. I mean, like, I remember like, I remember I saw stills from this Paris Hilton sex tape, but it looked like they were performing door-to-door raids in Fallujah.

Speaker 1 In Fallujah, yeah.

Speaker 1 But, like, but like, but 9-11 is like the years that followed 9-11 and like the Bush war on terror or war on Iraq years.

Speaker 1 You see the like, because like it took popular culture a while to catch up to like what the war on terror actually was.

Speaker 1 And I think only now we're sort of like finally having a culture that has caught up to that era or like is beginning to communicate or like to sort of express the reality of what that what that was and like have a culture that catches up to it.

Speaker 1 But like in the two in the Bush era, in the war on terror era, we still had a popular culture that was like Total Request Live, the P Diddy, the frictionless, endless optimism,

Speaker 1 but it had curdled and it had curdled and it had gotten and it was starting to go off. Like, what are some examples of that?

Speaker 2 Well, right. So basically, the classic one is the Clear Channel memorandum, which I think you've talked about on your show

Speaker 2 a couple years ago with Felix.

Speaker 2 So this was an internal memorandum from what's now iHeartRadio where they were basically like, hey, guys, considering this tragedy, we should maybe not play certain songs. And

Speaker 2 okay, maybe, but some of these songs were like the entire, the entire

Speaker 2 like discography of Rage Against the Machine because they criticized the United States and it was considered

Speaker 2 inappropriate to criticize the United States after 9-11.

Speaker 2 Oh, the other thing too is like the really interesting thing is that the line that people were saying after 9-11 is, well, like in the immediate aftermath, you would get like peace and love, and let's all like donate to our local blood bank type of messaging, which is great.

Speaker 2 I think that that's positive. But, but what you really got, what Eclipse did almost immediately was talk about being patriotic.

Speaker 2 The only appropriate way to respond to 3,000 people being murdered was to be patriotic, to fly your American flag, to wear your American flag t-shirt,

Speaker 2 and absolutely do not cons don't even consider

Speaker 2

critiquing the U.S. government because that's unpatriotic.

Oh, also go shopping. George Bush told us to go shopping.

Speaker 1 Khaled, was it you who shared that quote from Fred Durst of Limp Biscuit when he was asked about the war in Iraq? And he was just like, yeah, shit, shit, it's really crazy.

Speaker 1

Like, it's times we're living in right now. We have no choice.

We all got to support our country. And by the way, our album,

Speaker 1

Girl's Asshole Smelling, is out next week. Please.

Yeah.

Speaker 2 Someone, no, it wasn't me, but I reposted that. And I was like, yeah, this is pretty much my book.

Speaker 1 That's, that's another, you know, but this is my thesis. This is my thesis.

Speaker 1 I guess when I think about it is that like,

Speaker 1 like I was saying, that there was like, there was a darkness inherent in the pop culture of the late 90s, but like the cruelty that undergirded all of it and like the kind of sadism became more pronounced in the war on terror years where it was still running the same pop culture algorithm, but the kind of the nastiness, the sadism of it started to come to the fore, I think.

Speaker 2

Yeah, and it got stupider. Like, we all got stupider.

This was the era of the swan and flavor of love and rock of love.

Speaker 1 Colette, like, when I think of a film that I think, like, it was released in the year 2000, but I think like it's very much of a part of like, of what is like the high canon of the Y2K era.

Speaker 1 I don't think you mentioned it in your book, but a film that I always think about in terms of like how it very funnily and very like accurately like sort of prophesies the coming of the 21st century is the film Bring It On.

Speaker 1 Are you familiar with Bring It On? Oh, yeah.

Speaker 2 Oh, I love Bring It On. Yeah.

Speaker 1 Bring It On is a great movie. It's very funny, but like essentially, like, I think it captures the hyper-sexualized teenage culture of the era where like...

Speaker 1 The entire community is essentially behind these girls as they perform their public rituals of boastful cruelty and teen and sort of like titillating teenage sexuality that's kept within the bounds of a very strict like as you were saying like sexuality is for women to display to a proud town and community not to be used by them to have sex for their own reasons.

Speaker 1 Yeah, also

Speaker 1 the other big part of that movie, which is about rival cheerleading squads in Southern California.

Speaker 1 Another big aspect of that movie is that the popular San Diego cheer squad of all white girls are only popular because it's revealed that they stole all of their dances from the uh the black high school in in

Speaker 2 los angeles oh god yeah and this is like what i think that's such a brilliant read of it too because like

Speaker 2 there was a lot of sublimated racial angst that came out in really interesting psychoanalytic ways so i have you know and i want to say here that like i talk about when i talk about like rap there were different kind of types of it at the time, even within popular culture.

Speaker 2 Like, I'm not talking about someone like Missy Elliott with what I'm about to talk about. She's much more like, I mean, she's also, God, talk about like creating the look of the future.

Speaker 2 I mean, she and like Timbaland were so essential in terms of creating this, like, it was like an Afro-futurism of like, oh, yeah, like, we're in the 21st century, we're going to be able to like transcend.

Speaker 1 And like, Timbaland's production sounded so futuristic, too. It sounded like very like sci-fi almost.

Speaker 2

Right, exactly. It sounds like it's right.

It sounds like it comes from the future and it's going to give us this wonderful, peaceful, new, new millennium that we're all excited about.

Speaker 2 But there was another trend within

Speaker 2

rap that I talk about. And I talk about it specifically in terms of how it was received by many types of white people.

And this was bling era rap.

Speaker 1 The sort of dirty South, like, you know, when New Orleans and Atlanta started to become like the cultural epicenters.

Speaker 2 Like the the classic, the classic, yeah, like the classic one is Bling Bling

Speaker 2 by BG featuring big timers.

Speaker 2 That's from 1999. And

Speaker 2 basically, all these guys, there's like a very young Lil Wayne in it.

Speaker 2 There's all these guys are just like hanging out at this mansion. They're driving around on speed boats, tossing money everywhere, flying around in helicopters and driving luxury cars.

Speaker 2

There are nude women, or not nude, but like women in bikinis dancing around. Scantily clad.

Scantily clad. Thank you, Will.

Speaker 2 Yeah. And it's just sort of this like this celebration of pure wealth and acquisition.

Speaker 2 And what ends up happening is you also have like someone like Jay-Z, I think, is a good example of this, but you have clips.

Speaker 2 you have a lot of other popular rappers at the time singing about like or rapping about like coming up in the drug trade and talking about sort of the nitty-gritty of like the violence and the sort of

Speaker 2 acquisitive aspects of the drug trade. And what I argue with actually with help from a couple academics, including Lester Spence, who has some good stuff on this.

Speaker 2 But basically what I argue is that this was a way for Americans to sublimate what was actually happening in our country, both in terms of how capitalism was operating at that point in time, which was just sort of this really.

Speaker 1 Low interest, easy credit, like endless money. Yes.

Speaker 1 And that, yeah, like, yeah, like the rap music shifted from a kind of an almost like a

Speaker 1 documentary style eye for like the stories of the informed by the lives of people who lived a criminal lifestyle into

Speaker 1 sort of an evolution of that where it became and I remember not liking this music at the time, which was a huge oversight on my, because I love all of it now. I love all of it now, too.

Speaker 1 But like, yeah, like to me, at the time, it just struck me as like a purely nihilistic expression of just like having money for no other reason than but also violence.

Speaker 2 Like oftentimes these, not always, but oftentimes these songs will talk about, you know, the violence that's required to obtain and keep the money,

Speaker 2 which really is not so different um from the violence that's required to obtain and keep money in any other sector of society it's just that this is you know a little bit more kind of maligned yeah like the other thing is uh there's there was a lot of military imagery in hip-hop at the time yeah no limit soldiers no limit soldiers right the tank with the tank comes onto the basketball court and shoots a missile into the backboard

Speaker 1 and then

Speaker 1 that was a great video

Speaker 1 we have to go we have to go back. We have to go back.

Speaker 2 We have to return. I know.

Speaker 1 I know.

Speaker 1

We have to return to tradition. I know.

But can we talk about T.I.? Yeah, please.

Speaker 2 Yeah. So

Speaker 2

T.I. has a song where he compares himself to the Taliban.

He says that he's wild as the Taliban, nine in my right, 45 in my other hand.

Speaker 1 I'll never forget,

Speaker 1 we were driving in California, Catherine and I, and she had never heard the Jay-Z and diplomat song, Welcome to New York City. Yes.

Speaker 1 And the line in that word, jewel santana in the chorus says we from home in 9-11 the place of the lost towers we still bang it and she he was just so like like perplexed and like i mean she just found it like it was it was so she was overjoyed to have a song of that era where rappers were immediately appropriating 9-11 as like the coolest thing and like that's why that's why new york still matters is because people flew planes into our buildings it wasn't new orleans or atlanta it was atlanta it was fucking new york where it happened yeah yeah fair point.

Speaker 1 But Colette, like during this same period, during this same Y2K period, is the exact era in American popular culture that saw the rise of rap music from being a genre into being the dominant pop music form.

Speaker 1 And conversely, the complete supplanting of rock and roll as like as an American pop culture product. Because like, unfortunately, I have to, I hate to say in today's world, rock and roll is dead.

Speaker 1 What do you think accounts for that? And why do you think like rap music was so perfect to as a vehicle to sort of communicate and anticipate like these trends you're talking about?

Speaker 2 Yeah, I mean, so there are a couple of people whose work I talk about, like I talk about Lester Spence, who writes about like

Speaker 2 how rap music essentially,

Speaker 2 or not all rap music, but like a lot of this type of rap music we're talking about essentially

Speaker 2 expresses like neoliberal ideas about personal responsibility

Speaker 2 and, you know, getting rich and all of this. And then

Speaker 1

I'm Richard Die Trying. That was another foundational album.

Foundational album of this era.

Speaker 2 And also,

Speaker 2 yeah, like there's, there's a section in that essay where I compare some Clips lyrics to some statements by Bill Clinton when he passed the Welfare Reform Act.

Speaker 1 Do you remember which Clips lyrics?

Speaker 2

Yeah, they said, put it on your, what did they say? Put it on the scale. Help your goddamn self.

get it how we live it. We don't ask for help.

Speaker 1 Yeah. And well, I mean, like, a lot of clips lyrics also reflect what was going on in the Arkansas airport when Bill Clinton was governor.

Speaker 2 Yeah, right.

Speaker 1 Moving a lot of snow in and out. Yeah, yeah.

Speaker 1 But like, what, but like, like for rock music, because like, you know, in the 80s and like in the early 90s, before the

Speaker 1 Y2K era, was like the last gasp of rock and roll in the grunge, in the grunge genre. Cause like, like, I remember

Speaker 1 Nirvana, Alice and Shanes, and Pearl J. Like, that was the

Speaker 1 first music that I listened to that was like my music.

Speaker 1 It wasn't just like my parents are like, oh, like, this is the Beatles, this is what we listen to, this is the music of our generation that I liked.

Speaker 1 But, like, the grunge era was really like, that was music for me as I came into adolescence.

Speaker 1 The prevailing message of grunge was like that kind of, it was the same kind of Gen X nihilism, but it was a real anger and depression about the world.

Speaker 2 Although it's interesting because because I do feel like rap at this point, like you were talking about earlier, like a lot of rap is kind of back. Rap is almost like the vibe of grunge now.

Speaker 2 It's like, oh, I'm really addicted to drugs and I want to die.

Speaker 1 And like, I don't know, like, and like, also, the rap music at that era, like, you know, for me, one of the most foundational songs of my youth is Wu-Tang Clinton's Cream, Cash Rules Everything Around Me.

Speaker 2 Cash Rules Everything Around Me, right.

Speaker 1 However, but like, it was a little before, but like, and you can tell that it is right on the cusp of that era because you think about it, like, cash rules, everything around me sounds very much in line with the get rich or die trying or sort of like bling-bling era of the early 2000s.

Speaker 1 But the actual lyrics of that song are intensely depressing. And they're basically about like just how poverty makes you insane.

Speaker 2

Yes, exactly. Right.

And the other thing I wanted to mention is I talk a lot about how like

Speaker 2 there really wasn't so throughout the 80s and 90s the reaction to the neoliberal turn which I know I have to define on a lot of interviews I do but I know here, hopefully not.

Speaker 2 But like the reaction to the neoliberal turn and sort of like this growing inequality,

Speaker 2 racialized in a lot of cases, was essentially just let's lock up a bunch of mostly black people in destroyed urban centers.

Speaker 1 Like as you remove manufacturing, as America deindustrializes.

Speaker 2 Yeah, deindustrialization.

Speaker 1 What are you going to do with all these people that like no longer have a place in the economy? Yeah.

Speaker 2

Right. And so essentially, like throughout the 80s and 90s, you had the growth of these surplus populations.

And through the Y2K era,

Speaker 2 it's just that there was this discourse during the late 90s and early 2000s that, well,

Speaker 2

the tide is rising and it's lifting all boats, but it's not. We're just like locking up the people who aren't rising with the tide, basically.

And I think that like...

Speaker 2 the way that this could be processed was through kind of mass

Speaker 1 mass popularity of particular styles of rap music because it did give you glimpses into this stuff but it sort of let you compartmentalize it in a sense now like to return to the question of rock and roll what was it like what it what was it about rock and roll that didn't that that that that was like out of place with the y2k era but i'm like because like you know like this like rock and roll had a brief moment coming back with the rap rock rap hybrid rap rock but like what what was it about like and then like the kind of indie rock boom loop like the strokes which is you know harkening back to like an earlier era of like the velvet underground and the stooges but like what was it about rock music that made it insufficient or like no longer be was relevant to like the the y2k era what do you what do you think the counts for that that's an that's an interesting question and no one's asked me that one yet i mean so the what i was saying i think was that there was there's a book uh called why why white kids listen to rap from 2005 by a former editor-in-chief of the Source.

Speaker 2 And he basically argues, Bakari Ketwana, he basically argues that after Kurt Cobain died, there's just this sort of void

Speaker 2

in terms of he was like the voice of that generation. And after he died in 1994, it kind of, it caused grunge to kind of peter out.

And then

Speaker 2 rap, which had already been, you know, growing throughout the 80s and 90s, was able to kind of fill this void of youth rebellion.

Speaker 2

Right. You know, at around that time, you had like the height of the careers of Big In Tupac.

And then, of course, you know, their deaths very shortly after. And so

Speaker 2 like, it was almost like, I mean, the way he argues it, and he also does have a sort of

Speaker 2

a similar read to what I was just saying about like. deindustrialization and all of this.

But

Speaker 2 yeah, he basically argues that it was, it was sort of contingent.

Speaker 2 It was just like, well, there's a hole in the marketplace and this is an interesting form of music and interesting innovative stuff is happening here and rock's feeling sort of stale.

Speaker 2 And so here we go. And it just sort of steps in and then it becomes the dominant kind of voice of youth rebellion

Speaker 2 and

Speaker 2 displaces rock, basically.

Speaker 1 It's interesting because

Speaker 1 we're living in a world now in 2025 where rock has been displaced.

Speaker 1 But I'm wondering if you noticed the interesting thing now is that country music is becoming mainstream in a way that it has never been in American culture.

Speaker 1 Because if you look at guys like you know, Post Malone, who was doing like, who's a white guy doing like rap RB stuff five, six years ago, he's putting out a country album now, like he's leaning heavy into wearing cowboy boots and fucking 10-gallon hats everywhere with the face tattoos and everything.

Speaker 1 But like,

Speaker 1 what do you make of this, like, the rise of country music now, like,

Speaker 1 fitting into this current, perhaps more right-wing era that we're living in now.

Speaker 2

Yeah, I don't know. I mean, I wonder, though, if it is necessarily more right-wing.

I mean, I don't know. We're definitely in a more right-wing era.

Speaker 2 Like, I've gotten asked about this a couple of times elsewhere, and I basically feel like

Speaker 2 in some ways we're sort of going back to the sort of like reactionary nihilist anti-politics of the Y2K era these days. But I also think it's different because

Speaker 2 the reason things were so reactionary and so anti-political in those days was because

Speaker 2 people generationally had not experienced things like the war, the decade-long war, global war on terror. They had not

Speaker 2 lived with or continued to live with the effects of the Great Recession. And so

Speaker 2 there are these generational events that shape cohort, that shape politics at a cohort level. And so you kind of can't say, oh, we're just totally redoing it because conditions are different.

Speaker 2 But yeah, I don't know i mean i sort of feel like and maybe this is just boring and not um i have to think on this more but my my kind of gut reaction is just that there's an opening in the marketplace again like people are i don't think people are like done with rap but they're like in the same way that they were sort of seemingly done with rock in the 90s but it is there is sort of a hunger for something different and i think just country's there and it's starting to you know fill the void

Speaker 1 I mean, like, again, like, this is just speculation on my part, but, like, I don't know if it accounts for it, but like, I guess what I, what I, what I would have, what is interesting to me about country music as a genre as compared to rap music is that the content of country music song, essentially the lifestyle, the goals that it is advertising to its listeners are essentially so much more attainable.

Speaker 1 Like,

Speaker 1 the world that country music describes is a world that is a world of, and I'm not saying, and I'm not saying this as a criticism of country music at all but it is a world that is predictable it's a world that is knowable and that it is small and containable in your own life you fit into it and the content of what is going to happen to you next day it tomorrow is somewhat similar to what happened to you today and like the touchstones of like your town your community the people in it are knowable and legible and that like that that everyday normal people

Speaker 1 like like you know like friday night you're going down you're gonna like you're gonna two-step you're gonna have a a shot of Jack Daniels, you're going to drink, you're going to dance, you're going to drive home, you're going to listen to the radio, you're going to have some beers with your friends.

Speaker 1 But, like, this is not a world of unimaginable wealth or of like unimaginable nihilism and contempt for being alive.

Speaker 2 Right. I think that, and I think that that's a good thing.

Speaker 2 And the other thing to remember, too, about country music is that even though it had this right-wing turn, basically, and like, well, actually, especially after, like, I would say, like, sort of during the 90s, but not even, like, particularly post-9-11.

Speaker 1 Toby Keith, we'll put a boot in your ass.

Speaker 2 Yeah, we'll put a boot in your ass. It's the American way.

Speaker 1

Which, to be fair, it is the American way. Another song.

That song. Well, that song does stop, too.

I mean, I got to say,

Speaker 1 I did like, I did like all those jingoistic Toby Keith songs.

Speaker 2 It goes as a song.

Speaker 1 Perhaps ironically, and then perhaps unironically, who knows at this point.

Speaker 2 He's also, to be fair, he's like, Like, here's the thing. I don't endorse putting a boot in anyone's ass, but I do think that

Speaker 2 it's a fair description of American foreign policy.

Speaker 1

Yeah, that's true. Well, I'll just remember RIP Chris Christopherson who said of him.

Oh, God. Guys like him did to country music what Pennyhose did to finger fucking.

Speaker 2 Yes, exactly. Right.

Speaker 2 Chris was like, you know, like a comrade. Like, I think that,

Speaker 2 I think it's important.

Speaker 2 to remember, like I was going to say, with country music, that it was not always right-wing.

Speaker 2 And in fact, for the majority of its um its history it was a not always right wing and in fact not even white well i mean one of the biggest country artists now is uh shibuzi is a black guy yeah and then yeah and beyonce do is doing her country album and what she's you know made very plain in in interviews is and things and is just saying that she's like re reclaiming it right she's reclaiming country um or i don't know if interviews i know she doesn't really like do interviews but whatever she's made plain that essentially she is

Speaker 2 reclaiming like a black, a specifically black lineage of country music that's kind of been marketed out of it.

Speaker 1 I was just going to think about like the politics of country music and Chris Christopher Sen.

Speaker 1 Have you ever seen like people people shared this clip when he died, but like it was an interview that he did with the Highwayman, the sort of country music super group with like him, Waylon Jennings, Johnny Cash, and Willie Nelson.

Speaker 1 And like the interviewer was asking like, you know, like, what do you feel?

Speaker 1 Like, how do you feel about American society today and Chris Kirs Alperson goes basically says like well we've got a government and a media that's not too different than Nazi Germany but other than that I think we're doing fine

Speaker 2 I think that was from 1991 too so he got it he got it yeah

Speaker 1 um Colette I've I've had a great time at talking to you and remembering of the these culturalist touchstones that have uh ordered both your and my lives but I guess like uh the the the the last area I want to discuss with you is like this this is a book very much about nostalgia.

Speaker 1 It's about your own personal memories and reflections on your life and like how these things connect to these larger shifts in political economy and culture.

Speaker 1 But, like, obviously, now in 2025, I've been like, I don't know how you feel, but I feel like I'm speaking for a lot of people where it really seems like it's never been worse than it is now.

Speaker 1

And it's not getting better. And it's like the dominant feeling is that it's only going to get worse.

So, understandably, people retreat more into the past and then

Speaker 1 nostalgia becomes a thing that becomes sort of like a,

Speaker 1 I don't know, like an anesthetic for living in a present of which there doesn't seem to be a future.

Speaker 2 I mean, that's why I wrote this book, right? Like the inspiration for this book, like. In 2018, I was like more depressed than I've ever been in my entire life.

Speaker 2

I mean, things seem like actually worse now, but just things in my personal life are a little better. So that kind of makes it more tolerable.

But

Speaker 2 yeah, like I found this letter from 1999 from this time capsule where I was like, oh, in the new millennium, I will attend Stanford University.

Speaker 1 Your time capsule letter was hilarious.

Speaker 1 You really called it. You really got a lot of it.

Speaker 1 You got a lot of it right. I mean, some things wrong, but I think the broad strokes you got correct.

Speaker 2 Yeah, we definitely started to quote unquote do something about our environment.

Speaker 1 But I guess guess what I'm saying is like,

Speaker 1 I don't think, I think nostalgia is like a natural human tendency. And like, I think there is something distinctly pleasurable about it.

Speaker 1 Like, and, but, like, we live in a world now, we live in a pop culture now that just seems to be only nostalgic. And I guess, like, do you have an idea about like when nostalgia stops being

Speaker 2 wholesome or like reverential or when nostalgia like at what point for you does nostalgia become a problem or become something bad yeah so yeah like i was saying i i was super into nostalgia in i mean i still am but i was like obsessively following these nostalgia y2k nostalgia instagram accounts and like only listening to music that i listened to in middle school during like you know 2018 which is like one of the worst years of my life um

Speaker 2 to to get away and to just like you said like have a reprieve from the present and

Speaker 2 One of the things I wanted to do in this book was not only explore the nostalgia specifically, but to explore what nostalgia means.

Speaker 2 And yeah, I basically think it becomes a problem when you retreat so fully into it that you basically say, well, there's nothing we can do.

Speaker 2 Everything was better in the past. Oh, well.

Speaker 1

And I guess like another point of your book is that like it really wasn't better. And it wasn't really better in the past.

All these same problems were there.

Speaker 1 It only looks better or like it only feels better to us because we were all like, you know, not adults then or not living in this,

Speaker 1 not having to live.

Speaker 2 That's part of it, but that's part of it. But also like, what I'm saying is like, to me, I see it, I see it as this analogy, right?

Speaker 2 So like, it would be like saying that, it would be like me saying, like, oh, um, my, my inflatable chair was really well made before I sat on it and it popped because it was constructed shittily.

Speaker 2 And, you know?

Speaker 1 Yeah, or like, I mean, I think about like, you know, we made fun of them on the show quite a bit, but like the sort of like right-wing sort of like engagement forming accounts where they're like, they've become nostalgic for like

Speaker 1 1994. Yeah, and like, you know, just sort of like

Speaker 1 an era in which like, you know, we were all alive in, but it was just sort of like the window for what you can be nostalgic about is getting shorter and shorter and shorter.

Speaker 1 And I think in like about five years' time, there's going to be this, there's going to be nostalgia accounts for like January 2025.

Speaker 1 And we'll all remember like, yeah, we'll all remember like how things look differently.

Speaker 1 But I think the problem is now is like the last, if you think about the last 20 years or so, like there hasn't been any of these big, noticeable shifts in like the way people dress or what things look like.

Speaker 1 It really just feels like we are living in an

Speaker 1 ever-expanding horizon of this kind of like of nostalgia, of a past that like never really stopped, but like of which there is less and less juice to be squeezed out of.

Speaker 2 Yeah, I mean, it's the Mark Fisher thing, right?

Speaker 2 Like we're all just stuck in this capitalist realist world where because we're trapped in this political economy that is like causing Los Angeles to burn and like causing Elon Musk to become like de facto God emperor, like we just feel like there's nothing.

Speaker 2 Yeah, we just all feel trapped.

Speaker 2 And it's not like I have any like special sauce for how we get out of this, but I think that it's a reaction to this sense that like, there's there's nothing that we can do.

Speaker 2 And I also trace this there's nothing we can do idea to like

Speaker 2

the late 90s neoliberal turn because it was like, hey, look at how great it is. There's nothing we can do.

And now it's like, wow, we live in hell. There's nothing we can do.

Speaker 2 I mean, but they're actually, I mean, I don't know. I don't, I'm not like a solutions person, unfortunately, but I mean, I ultimately believe that if there was some kind of

Speaker 2 like forward-looking left project that was focused on like essentially like

Speaker 2 increasing union power and like

Speaker 2 regulating fossil fuels and other, you know, dangerous business idea.

Speaker 1 How will most people like live in the coming century?

Speaker 1 Are we going to make it easier for them or harder for them?

Speaker 2 No, exactly. We need to have, there needs to be some kind of project that is forward-looking that says, hey, here's a radically different idea.

Speaker 2 We've had the like, like one of the things I talk about, so I have an essay in there about California because I spent a lot of time in the Bay Area as a kid because I have family there actually who

Speaker 2 was participating in the dot-com bubble. I write about like

Speaker 1 you say that like it was like

Speaker 1 they were like did the Holocaust or something.

Speaker 1 Unfortunately, I have several family members who participated in the dot-com bubble.

Speaker 2 Well, yeah.

Speaker 1 They fell out of a guard tower at Google or Pets.com.

Speaker 2 No, honestly, it actually wasn't like, and I'm not just saying this as like defending my own family, but actually it was like, it was a communications company in the late 90s.

Speaker 2 So it wasn't like, it was like, hey, this is decent, you know?

Speaker 2 This is like, this is like, at least this is something that sort of socially has some kind of social value versus whatever the hell is going on there now.

Speaker 2 But like, I talk about California and the two visions of the future that it can offer.

Speaker 2 So the future that I saw in California when I was a kid, when I wanted to go to Stanford University, like this family member had,

Speaker 2 and and like all of my idols did like Chelsea Clinton I loved Chelsea Clinton as a kid

Speaker 1 she was the first kid she's the first

Speaker 2 yeah and and

Speaker 2 you know but I talk about I talk about California seemed like it would bring us this wonderful future future full of transparent computers and this wonderful peaceful internet and eternal pros and endless prosperity for all.

Speaker 2 And then what it actually brought us was like tech oligarchy, self-driving cars that crash into each other and giant wildfires.

Speaker 1 Yeah.

Speaker 1 And like

Speaker 1 AI prompt bars that will be like, oh, show me a picture of Tony Soprano riding a horse or, you know, into into,

Speaker 1 I don't know, into a ball pit at Chuck E. Cheese.

Speaker 1 Yeah, the creation of that image required 10 million gallons of fresh water to produce.

Speaker 2 Right, right, right. But what I talk about,

Speaker 2 you know, and also, God, speaking of like stuff, you know, predictions of the future,

Speaker 2 I had this experience when I was 10 where I'm walking around San Francisco with my uncle and I wandered off and this homeless guy starts screaming at me. And I'm like, what the hell is going on?

Speaker 2

Because I'm like from the suburbs of D.C. and didn't have a lot of experience with that sort of thing.

And at the time, you know,

Speaker 2 I was just like, well, that was weird. And now I kind of look back and he almost is like the ghost of the future in a way, because it's like, this is what's the problem.

Speaker 2 This is going to be a massive problem in the 21st century, right? So you have, yes, you have like, you have sort of the utopian California, you have the dystopian California. But basically

Speaker 2 the problem with the utopian California is it created the dystopian California

Speaker 2 in a lot of ways, right? And

Speaker 2 so what I would like to see is a forward-looking project

Speaker 2 that

Speaker 2 gives us, that like gives us a vision of a future that's like hopeful and livable and like makes people excited about like being alive. And it just doesn't feel like we have that right now.

Speaker 1 No, it does not. But

Speaker 1 to quote another Wu-Tang song, can it be that it was all so simple then? Can it be? And the answer is no, it was never all so simple.

Speaker 1

I think we should leave it there. Colette Shade, thanks for joining us.

And the book is Y2K. We will have links in the episode description.

Speaker 3

I wanna lick, lick, lick, lick you from your head to your toes. And I wanna move from the bed, down to the down, to the to the flow.

When I wanna, I, I, you make it so good, I don't wanna leave.

Speaker 1 But I gotta, lift, lip, lift, know, what's your your back to say? I wanna get you in the door.