899 - Nut Up feat. Yasha Levine & Rowan Wernham (1/13/25)

Watch The Pistachio Wars documentary now: https://www.pistachiowars.com/

Press play and read along

Transcript

Speaker 1 Hello, everybody. It's Will here.

Speaker 1 And before we get into today's episode and guests, I would like to enlist your support, you are wonderful listeners, for your participation in this upcoming Thursday's episode, in which we are once again doing a call-in show.

Speaker 1 So please use this as my plea to, if you'd like to submit a question for us to answer on Thursday's show, we would love to hear from you. Any queries that you'd like to pick our brains on?

Speaker 1 Politics, pop culture,

Speaker 1

personal questions. We'll give some advice.

We'll answer your questions.

Speaker 1 But your instructions, should you wish to participate in our Thursday call-in show for episode 900 of Chapo Trap House, is to email a voice note or recording of yourself asking a question.

Speaker 1

And please limit yourselves to 30 seconds or less. If it's over 30 seconds, we will not consider your call.

But please email a voice note or recording of your question to calls at chapotraphouse.com.

Speaker 1 Once again, if you'd like to submit a question for this upcoming Thursday's call-in show,

Speaker 1 the address to email your recording to is calls at chapotraphouse.com. Without any further ado, let's get to Monday's episode.

Speaker 1 Hello, everybody. It's Monday, January 13th, and Chapo is coming at you.

Speaker 1 Obviously, since last week's show, very much the catastrophic wildfires that have devastated LA are very much at the forefront of our mind.

Speaker 1 So, I figured for Monday's episode, I would have on a guy who has been covering the water beat in California for many years.

Speaker 1 So, and now also joining us with his co-director has a new documentary out about the pistachio wars in California. So, a very, very appropriate time to talk about water in California.

Speaker 1 So, without any further ado, I'd like to welcome to the show Yasha Levine and his co-director on the new documentary, Pistachio Wars, Rowan Wernham. Rowan, Yasha, welcome to the show.

Speaker 2 Yo, hey, hey, hey, thanks for having us on.

Speaker 1 Well, first of all, congratulations on finding the perfect news hook to your documentary.

Speaker 1 I know that a lot of people are assessing blame for these wildfires in California, but I have heard that mobs of Antifa are pouring gasoline into the sewers.

Speaker 1 And I'm wondering, Yasha, were you involved in that at all, just to get people interested in this documentary?

Speaker 2 Yeah, yeah, yeah. I mean, I was definitely, I mean, well, I can't, I don't want to say anything, but if you follow my Venmo history, I think you'd be able to connect the dots.

Speaker 1 You know,

Speaker 3 it's going to go down in history as one of the most destructive marketing campaigns.

Speaker 1 But one of the most destructive, but hopefully one of the most effective as well.

Speaker 2 Well, you have to, you have to destroy to create, you know, that's the main, that's the main thing, you know? Um, yeah.

Speaker 1 All right. Well, if any of you were in Brett Easton Ellis's neighborhood, I just please, please stop pouring gasoline into the sewers.

Speaker 1 But obviously, like, so the wildfires that have, like I said, devastated Los Angeles, I mean, assessing blame for this or like trying to figure out why or how something like this could happen is a long story, but it obviously has to begin with water.

Speaker 1 So, Yasha,

Speaker 1 I'll start here. Who owns the water in California? And is like, is the owner, is it water ownership in California, is it an outlier as far as like the rest of the states in the union?

Speaker 1 Or is California an extreme example? Or

Speaker 1 is it unique in how water is managed and owned in the state of California?

Speaker 2 Yeah, I mean,

Speaker 2 I think California, but I think just generally the Southwest. you know,

Speaker 2 sort of the dry desert states,

Speaker 2 they do stand out from the rest of California, from the Midwest or from the East Coast,

Speaker 2 because

Speaker 2 usually like development is happening or takes place or farming takes place where there isn't any water. And so,

Speaker 2 you know, getting control of water, right, and moving water to where it's needed, you know, is like central. So

Speaker 2 water ownership and

Speaker 2 control of water and control of water systems that deliver this water is unique to the West, to the Southwest.

Speaker 1 It is unique unique to america so there is a very particular thing that's going on you know in california that it doesn't take place in the rest of the country for the most part yeah i mean what's like not unique to california is that like a lot of things it's supposedly public resource but it's basically quasi-privatized so there's numerous ways that industry has captured control of the water uh even though technically they're not supposed to have yeah so one of the one of the words you use to describe uh southern california that i really like is terraforming And like really like the human settlement of the massive like development of Southern California is a project of terraforming, like similar to what you would do to like, I don't know, Mars or something like that.

Speaker 1 And water is a crucial part of that. But like the sort of the mechanism of terraforming Southern California is largely controlled by a cartel of real estate developers and industrial agriculture.

Speaker 1 Could you describe like that that partnership and how it has led to things like what we're seeing in California now with these devastating wildfires.

Speaker 2 I mean, you know, I think

Speaker 2 probably the best thing, what a lot of people could have a cultural reference, kind of a cultural understanding of it, is the movie Chinatown, right? I mean, it's kind of about that process.

Speaker 4

Oh, that's all taken care of. See, Mr.

Gibbs,

Speaker 4 either you bring the water to LA

Speaker 4 or you bring LA to the water.

Speaker 3 How are you going to do that?

Speaker 4 By incorporating the valley into the city. Simple as that.

Speaker 2 It's about creating systems that move water around, right? And then essentially taking water and sort of sucking areas of life,

Speaker 2 basically sucking them dry and killing them in one place, taking that water and bringing it to another place so sort of like artificial life can bloom, whether it's like a suburban sprawl or some kind of monocrop like pistachios or alfalfa or cotton like that.

Speaker 2

You have to move water around. And it's a huge state.

So you basically the system works like this.

Speaker 2 You have

Speaker 2

most of the water in California is seasonal. It only falls in the winter for the most part.

Also, it's sort of concentrated in the mountains, a lot of the water.

Speaker 2 So, it falls also as snow in the mountains. So, what the system sort of does is there are these huge dams that are built in the mountains, more to sort of north of Los Angeles.

Speaker 2 Some of them are kind of slightly north of Los Angeles.

Speaker 2 Others are really like far north. Like, I'm talking about, you know, 600 miles north in Los Angeles.

Speaker 2 And these dams capture water, you know, behind these giant reservoirs and these artificial lakes high up in the mountains.

Speaker 2 and then there is this whole system of concrete rivers and pumping stations and switches and gates and all these things. And it's all kind of computer controlled that basically moves this water.

Speaker 2 It moves this water, you know, for hundreds and hundreds of miles around the state. So, I mean, essentially redirecting the natural flow of rivers and the natural flow of water throughout the state.

Speaker 2 And it has to, this, like I said before, this has to be done because where the cities are, kind of in these lowland valley areas, where the farms are, there isn't a constant supply of water.

Speaker 2 It just, it just, there isn't enough water to sustain life on a massive scale. So, let's say if LA didn't have these massive systems feeding it, it'd still be like a little town.

Speaker 2 It'd be like a little Pueblo, essentially, like a shit kicker town, you know, like that you'd see in a Wild West movie or something like that, because there's not a lot of water there.

Speaker 2

And so, in order to sustain massive development like the kind that you see today, LA gets water from three sources. All the sources are hundreds of miles away.

One is the Colorado River.

Speaker 2 It basically there's a canal that goes across state lines into Arizona that grabs water from there.

Speaker 2 Another canal, another source of water is like 350 miles away and about 4,000 feet up in the mountains. It grabs water from the Sierra Nevada mountains.

Speaker 2 Another source of water is sort of even further up north, where this, you know, Mount Shasta area, that's about, I think, 550 miles away.

Speaker 2 So LA is like this octopus that has all of these tentacles kind of spread around, you know, far, far away, almost like an imperial octopus that's sucking water from all around, right?

Speaker 2 Destroying those areas, you know, killing life there, but and redirecting that life force and that life energy to LA so that it can, you know, build suburbs without end.

Speaker 2 So it can build up in the mountains, in the hills, in these areas where, you know, that are very fire prone that we've seen kind of burning, you know, in the last week.

Speaker 2 I mean, that's the terraforming system, and it's vast and

Speaker 2 it's been slowly built out over the

Speaker 2 plus or minus, you know, last century. And it has all these different components, but it is the largest sort of terraforming aqueduct canal system

Speaker 2 in

Speaker 2 the world, you know, in human history, like way better than anything that the Romans had or anything like that, you know.

Speaker 1 Rowan, you mentioned that, like, water, water is, or at least theoretically, is a public resource in California. But, like, what are some of the ways in which it is really not?

Speaker 1 Or that, like, how, like, how can so much water be privately owned in a supposedly public system

Speaker 3 yeah well i mean um i mean if you look at the wonderful company for example uh when you get out into the central valley which is where all the industrial farming is um you have like localized water districts so uh you know they've got the westlands water district and they're like supposedly public utilities but the control of them goes is based on land ownership

Speaker 3 so you know because the wonderful company essentially owns like half of the west side of the valley they have complete effective control of the Westlands Water District.

Speaker 3 Uh, then, like, the Westlands Water District, with negotiations by like the Resnicks and some other big water owners out there, there's a few other big companies like the Boswells and you know, other old families, they kind of pushed the state to give up this thing called a water bank, the Kern Water Bank,

Speaker 3 which is kind of like this underground aquifer that can store enough water to supply LA.

Speaker 3 Uh, you know, kind of in the 90s when privatization was the ideology, but also, you know, whatever, no one really knows, backroom deal.

Speaker 3 The Resnicks didn't give up very much.

Speaker 3 They kind of gave up some water rights to water they probably wouldn't have gotten, like this kind of like crazy system in LA of water rights where, you know, it's based on an abundant year, but usually there's maybe twice as much, half as much water, you know, as there is water rights for in any given year.

Speaker 3 So they gave up some water that didn't really exist to get this water bank.

Speaker 3 And yeah, you know, like, I think like when you think about America as a whole, it's always against centralized government, you know, like the idea that the government in Sacramento or whatever could make decisions.

Speaker 3 So they've broken it up into these little water districts. And the water districts in the center of California are very sympathetic to industry.

Speaker 3 So they tend to just be effectively run by the local industry and make all the decisions about water allocation based on those businesses.

Speaker 2 I want to add one thought to this is that like you have to kind of to understand, I think, you know, how water can be privately owned if it's like a public resource.

Speaker 2 You kind of, yeah, I think you have to go back to the very beginning of the state and the way that like what the political forces were in play, you know, when California kind of became what it is today right after the gold rush.

Speaker 2 And essentially, farmers and ranchers were like the original power base of California, right? Like, so agriculture, that was like the, they, they ran. California.

Speaker 2 And so successively, they kind of built these sort of government structures that are, you you know, on a kind of a superficial level, publicly owned and controlled by public water agencies that are, you know,

Speaker 2 run by these people appointed by a democratically elected governor and all these things, right? But these structures serve agricultural interests.

Speaker 2 And because agricultural interests are intertwined with a real estate interest, because it's all about land, you own, you know, a chunk of land can be a farm, it can be a suburb.

Speaker 2 It doesn't really matter. And in fact, a lot of farms in California became suburbs, like the entire Orange County essentially were orange groves, right?

Speaker 2 And so they were flipped and now they're like, you know, just a continuous suburban sprawl. And so you have farmers that are at like the core political

Speaker 2

or core political power. And that hasn't really changed much, you know, and they're like local.

So they're not like coming from New York City.

Speaker 2 There is like obviously some Wall Street connections and stuff like that, but they're like, it's like, it's homegrown, it's local, and they are really at the at the core of power in California.

Speaker 2 And so even if like the water that they get is paid for by taxpayers or heavily subsidized by taxpayers, the entire water system is controlled by the government, built out by the government, both the state government and the federal government.

Speaker 2 The farmers and the sort of the real estate developers who are the ultimate beneficiaries of this water aren't

Speaker 2 in essence in full control of the system. So

Speaker 2 it's a de facto privatized, right? Like because it's private control over public resource, if that makes sense.

Speaker 1 Yeah.

Speaker 1 I mean, like, so, you know, when these wildfires happened and then they're still going on, a lot of the news headlines are about people's outrage about the fact that like there wasn't enough water in the reserve reservoirs.

Speaker 1 There wasn't water coming out of the fire hydrants when firefighters are trying to put out these fires.

Speaker 1 So obviously to have a city of 20 million people in the middle of a desert takes, you know, as you as you pointed out, it takes moving an astonishing amount of water over an astonishing distance to like make life possible in places like Southern California, Los Angeles County.

Speaker 1 So like, is it a matter of like there's just not enough water in California or is it a matter of how like the water resources are utilized, like where they go?

Speaker 1 Like, so what do you think accounts for the fact that like there were no water coming out of the fire hydrants in LA?

Speaker 2 Well, I could answer that because I kind of looked into it. I mean, that

Speaker 2 has nothing to do with like, you know, water allocation on like this bigger scale because the reason I think

Speaker 2 you know, basically water pressure fell because there was so much water being used to put out these fires. And because essentially,

Speaker 2 they have to pump water into these giant water tanks that

Speaker 2

sit in the hills and that essentially provide kind of like water pressure. Like in New York, you'd have water tanks on top of on the roofs of buildings and stuff like that.

So they essentially

Speaker 2 use so much water that

Speaker 2 there's no water pressure in the fire hunters' lines. I mean, there was another thing, there was a one reservoir that was kind of offline because they were fixing it.

Speaker 2

But Los Angeles is like, controls more water than any other entity in California. I mean, LA is has a huge amount of water right now.

There isn't a lack of water that LA has, right?

Speaker 2 So it isn't about like that there isn't, I know that there's basically these sort of me, there's like these kind of funny things.

Speaker 3 We have a like a thread going at the moment that somebody has watched our film and just posted like a thread that's gone to like millions of people about how the Resniks, you know, are to blame for the water.

Speaker 3 I mean, it's, it's kind of like there's so many things that you can blame them for that they're getting away with.

Speaker 3 It's like you don't really want to to do their public relations work and pour cold water on this one.

Speaker 3 Because, you know, like Yasha said, you know, it's probably a bit more indirect. You know, the causes are more indirect and systemic.

Speaker 3 But yeah, like it's kind of like a local water problem with the flood.

Speaker 2 Well, but I but it's connected in a way that I think, you know, I think, you know, I would to give these sort of influencers like who have kind of problems, I don't know, reading comprehension issues or whatever, you know, like to give them credit, because I kind of

Speaker 2 sympathize because they're more right than wrong because the the Resniks

Speaker 2 are tied into this larger, like terraforming aqueduct system, right?

Speaker 2 And the way that water is allocated and who gets to control or decide how that water is allocated are basically people who are involved in real estate development and people who are farmers.

Speaker 2 And frequently those two parties can overlap pretty heavily.

Speaker 2 And so the way that the Resniks are tied into the system that is kind of responsible for the fires because the system has allowed development in the Los Angeles area to just go unchecked.

Speaker 2 You You know, they're just built out homes in areas where they shouldn't be homes, largely because they have access to water that can be put anywhere, right?

Speaker 2 And it's because of this terraforming system that creates a sort of artificial layer of society.

Speaker 3 And so like when you, when you have like the water bank we talked about before as well, it's kind of owned by farmers, they're selling water to suburban developments.

Speaker 3 And

Speaker 3 often when you have like the lobbying, the Resniks are going to be a big party lobbying to bring water, say, from like the Delta, the the river that feeds to San Francisco Bay south and to build this infrastructure.

Speaker 3 But, you know, they're also going to be in partnership with the Metropolitan Water, you know, the LA Water District and real estate developers.

Speaker 3 So they're all working together to achieve the same things,

Speaker 3 even if it's like suburban development versus agriculture that. might be the real problem here in the fires.

Speaker 2 I mean, the main thing is this. It's like, I think the takeaway message for me is like, California is this very like artificial civilization, right?

Speaker 1 Everything is built in places where they it shouldn't be you know like it's like building it it's like building at the bottom of a river you know during during a dry spell and the decisions are like purely profit-driven as well just like opportunistic short-term profit i mean when i think about i want i want to get into the resniks and the wonderful company and just like the pistachios in general uh but before like but along the lines of what you're saying like as someone who didn't grow up in california who is just merely a visitor of california if you've never been or you visit there for the first time chances are you're going to be in LA or San Francisco, the two major cities, but like you're going to see the Pacific coast of California, which if you're visiting it for the first time, seems like paradise.

Speaker 1

It seems like heaven on earth. It's like one of the most beautiful parts of the country.

You think, oh my God, like, why, why doesn't everyone just live like this?

Speaker 1 But then I'll never forget the first time that I drove from LA to San Francisco through the Central Valley.

Speaker 1 And the first time you see the Central Valley, if you've never seen it before, it is one of the most disturbing things I've ever encountered.

Speaker 2 It really feels, it feels like the apocalypse.

Speaker 1 It's like six hours straight of just driving through what could be the surface of the moon, basically. But it's just like.

Speaker 3 And it used to be beautiful.

Speaker 1 It used to be a river valley,

Speaker 3 you know, like a river valley full of birds and wildlife and stuff.

Speaker 3 That's the crazy thing about it. It was like the California, like the savannahs of Africa.

Speaker 3 But there's no record of it because as before, we kind of got there with. invented video cameras and things.

Speaker 1 Well, yeah, I mean, it just like I, that doing that drive, I mean, I just remember the first time time I did it, I was just struck by the feeling that like this is what the end of the world looks like.

Speaker 2 It's a it's scary, man.

Speaker 2 And it's one of the things that why I this this this topic, you know, of the water and the history of California and like the the and essentially sort of the I guess the larger story is like how the West was colonized and developed and sort of exploited, you know, how it fascinated me because like

Speaker 2 I when I came from the Soviet Union, my, you know, we we moved to Brooklyn and then to San Francisco. And so I grew up from the time that I was nine years old in San Francisco.

Speaker 2 And, you know, I went, like, I swam in all the fake reservoirs that in California they call lakes. You know,

Speaker 2

I drove through the Central Valley so many times and also just wondered at how just bleak and miserable it seemed. And you just, you try not to think about it.

You just try to get past it.

Speaker 2

You know, and I think you try to go as fast as possible. You know, I got once pulled over.

I was like going like 115 miles an hour. at night and I didn't even know I was going that fast.

Speaker 2 Like I was like a cop. I saw a cop do a U-turn from the other side of the highway to chase me and and I was like, man, who is he chasing? Like that's how fast,

Speaker 2 that's how much you want to just get past that shitty.

Speaker 1 Well, I mean, you can zone out because like there's literally like you don't have to turn the wheel at all. It is just straight.

Speaker 1 No brake.

Speaker 1 And everything you see out of either side of your window looks the same for

Speaker 1 six hours.

Speaker 2 And the Resnicks, you know, we can get to it a little bit later, but they own so much land that like you could be driving for an hour and still essentially be like a budding one of their properties.

Speaker 2 Like it's a it's a bleak thing. And look, and that's kind of what

Speaker 2 this is what California is. It's like this totally

Speaker 2 artificial place where

Speaker 2 water, you know, again, like what Rowan was trying to say before, actually, the Central Valley used to be a kind of a beautiful, pleasant place to be because it would just be seasonally very lush in the winter when it would rain, and all the rivers that weren't dammed would drain into the Central Valley, and it would become this.

Speaker 2 the largest freshwater lake in

Speaker 2 like, you know,

Speaker 2 in America, right?

Speaker 2 Seasonally, and then it would slowly dry out and there'd be like there'd be bears there'd be elk there'd be like all these all these um all these birds that would just you know be huge flocks of birds so it was full of life it was lush and so but what happened was all the rivers are dammed water no longer comes down into the into that valley and all that land because it's so fertile from the thousands and thousands of years of uh you know sediment runoff

Speaker 2 that's sort of naturally nutrient-rich land, it's like been turned into a giant factory, you know, an outdoor factory where it's monocrops, it's just industrial agriculture, it's just there are no people on these farms.

Speaker 1 Like you can drink, you can like-that was the thing that was so disturbing to me about it.

Speaker 1 It was like six hours, and the only people I saw were in cars. Like, you do not see human beings.

Speaker 1 I mean, the only life, I mean, other than plant life that you see is like the stretch where you go through, Yasha, as you described it, Kauschwitz,

Speaker 1 the huge, where it just smells like death for an hour straight.

Speaker 2 Yeah, yeah. No, it's, it's a bleak, it's a crazy bleak place.

Speaker 2 I mean, it's what I do kind of imagine if Mars was ever terraformed, you know, and there was like some kind of semblance of atmosphere that was like put there. I mean, that's what it would be like.

Speaker 3 It's a little bit warmer up there in Mars.

Speaker 2 Yeah, that's what it would be like. And yeah,

Speaker 2 it's a, it's an engineered, it's a totally engineered landscape in the desert, you know? And so it's

Speaker 3 and it's been plundered by, you know,

Speaker 3

successive extraction industries. So oil has been in there.

Farming now is basically an extraction industry, just taking the water and turning it into cash in a completely unsustainable way.

Speaker 3 And of course, real estate development, you know, the gold, you know, gold was the original, you know, basically the reason everyone came here to ruin the place.

Speaker 2 Yeah, gold, silver,

Speaker 2

you know, then agriculture, then suburbs. You know, now it's, I don't know what it is.

It's like

Speaker 2 they're going to mine woke. Out there from the

Speaker 1 water they need to create funny AI-generated images.

Speaker 1

Everyone can do that. That's right.

Yeah.

Speaker 2

Exactly. Yeah.

No, it's fucking brutal. Yeah.

Speaker 1

All right. So, like, you've brought them up.

So, like, let's talk about the Resnick family and the Wonderful Company, which I think is an aptly named

Speaker 1 corporation for them to

Speaker 1 be in charge of. The wonderful people, the wonderful company, the Resniks, who have, Rowan, as you mentioned, has sort of been pegged as next to, I suppose, Karen Bass and Gavin Newsom, the kind of

Speaker 1 culprits of this latest disaster. Could you talk about who the Resniks are, where they come from, and like this pistachio empire that they are sit at the top of?

Speaker 2 Oh, yeah, yeah.

Speaker 3 Well, I mean,

Speaker 3 it is funny that the Resniks are getting pulled into this. I mean, it's, you know, it's great to see it

Speaker 3 because they kind of have flown under the radar, I think.

Speaker 3 You know, they're these billionaires that you might have seen their name on, you know, the museum at LA, LACMA, Hammer Museum, they're big donors to the arts.

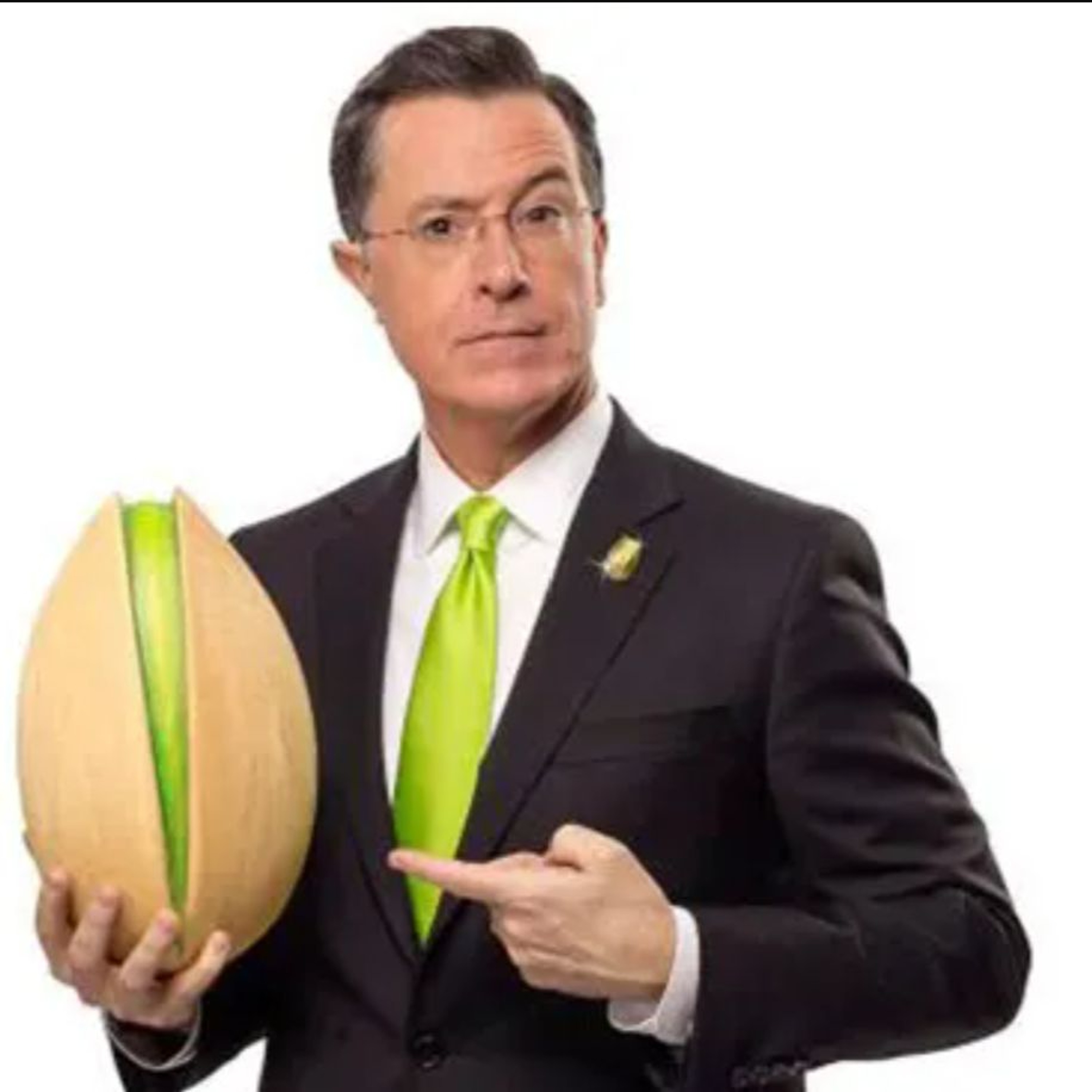

Speaker 3 You know, they've kind of got this liberal image. They've got Colbert as they mascot.

Speaker 3 They live on Sunset Boulevard. They're going to the biggest mansions there.

Speaker 3 And they happen to be the biggest nut farmers in the world.

Speaker 3 They've kind of built this pistachio empire, this wonderful company with all this crazy marketing.

Speaker 3 So, I mean, Linda and Stewart, yeah, they're like an interesting couple.

Speaker 3 We kind of go through it all in the film, so you should go and watch, go to pistachiowars.com and watch the movie. I'm just plugging it in the middle of my speech here.

Speaker 3 You know, like Stewart came from New Jersey. He's kind of like,

Speaker 3 you know, had a pretty rough start to life, might have kind of grown up around his dad, might have been adjacent to the mob or something like that, he says sometimes.

Speaker 3 And he escaped that, came to California to make a better life and had a whole pile of businesses that just did really well.

Speaker 3 You know, like a janitorial business that was suddenly a $10 million business.

Speaker 3 And then a security company, like a college student, you know, and then he had a security company who was doing security at LAX

Speaker 3 with like a chief of police running it.

Speaker 3 And they got busted smuggling like large blocks of heroin through LAX. You know, basically, they were running the TSA.

Speaker 3 So, you know, at the time they said it was a mob-connected company.

Speaker 3 You know,

Speaker 3

nothing's ever really come of that. But, I mean, that was what happened at the time.

So he had a lot of money. He met Linda.

Speaker 3

Linda was the child of like a Hollywood producer who made the blob. And, you know, she kind of came from Pennsylvania to Hollywood with her dad.

And she was kind of like a marketing protege.

Speaker 3 So, you know, at the age of 19, she started a marketing agency you know she was kind of like around the radical counterculture so she has this moment in history where

Speaker 3 she

Speaker 3 was dating one of the guys that leaked the Pentagon papers and then she got pulled into the indictment and you know you know whatever I don't know

Speaker 2 I mean the story is that she actually Xerox the Pentagon papers

Speaker 3 her yeah at her marketing agency in her office yeah so and uh yeah anyway so they met when she was pitching this agency and they I don't know what it's some beautiful fireworks exploded and they got together and just started building a business empire, but buying up companies like they bought up the Franklin Mint and Teleflora, these kind of trinket companies and things they could market, maybe move drugs with, who knows?

Speaker 3 The speculation.

Speaker 1 Don't quote me.

Speaker 1 Is it harder to cultivate poppies or pistachios? I have no experience cultivating poppies.

Speaker 2 I actually do have some experience cultivating poppies for purely aesthetic purposes, you know, decorative purposes.

Speaker 2 And I think it's I think it's a lot more labor and capital intensive to plant pistachios, you know, just because

Speaker 3 they're stealing the pistachios from Iran, whereas the poppies, I guess, Afghanistan, so it's naturally next

Speaker 2

target. California would be a fucking incredible place to grow some poppies, I'm just saying.

You know, like

Speaker 2 I don't know why they don't

Speaker 2 take back our drug industry, it would be more sustainable, you know, local and all that.

Speaker 3

Yeah, I think it's great. Let's make that the takeaway.

Like, stop pistachios, grow, grow poppies.

Speaker 1 For

Speaker 1 I mean, like, well, I mean, like, like an aspect to pistachios in particular, but also almonds as well.

Speaker 1 I mean, like over the last 20 years, there's been this huge explosion and like almond milk and almond-based lotions and almond products.

Speaker 1 These nuts are incredibly, they take an incredible amount of water to produce even one nut. Like, what is it, like a thousand gallons of fresh water needed to create like how many?

Speaker 1 What, one pistachio or like one pound?

Speaker 1 One pound of pistachios, yeah.

Speaker 3

Something like that. You know, it's a lot of water.

And there's there's also this factor where they need like constant water.

Speaker 3 So, you know, other things, if you're just growing vegetables and like, you know, normal food that people need to eat, you can just not plant your crops if there's a bad year or drought.

Speaker 3

But the pistachios, they just constantly need the water. Otherwise, you've got to rip out the orchard.

It takes about seven years before you can start like basically harvesting.

Speaker 3 So there's this huge political pressure that comes from the nuts. Because no one wants to rip out their orchards if they run out of water.

Speaker 3 So they increase the lobbying and they increase their control and their grip on water infrastructure.

Speaker 3 And I mean, you know, mistachios are particularly pronounced because the wonderful company kind of has a monopoly. They basically created the market with advertising.

Speaker 3 So they did these crazy Super Bowl ads and stuff and put them everywhere.

Speaker 1 Well, you said the wife comes out of a marketing background. So, like, how has her skill in marketing been led to the Resnick sort of

Speaker 1 supplanting a lot of these, like the older oligarch families? Like, for instance, Nellie Bowles' family.

Speaker 2 Yeah, yeah. I caught I like to call her bowels you know I don't know so Nellie Bowles

Speaker 2 I don't know it just somehow fits her better but you know I'm an immigrant I can't pronounce things so I don't know

Speaker 2 yeah well yeah I mean look it's they're interesting I mean in a way they're they're they are like they represent a newer kind of

Speaker 2 like hungrier greed I don't know greedier but just hungrier you know generation of people because yeah, farming really goes back to this little clique of families that had essentially intermarried and like created this aristocracy um you know going back to again like around the gold rushes when all these families established themselves um people

Speaker 2 you know in these clans intermarried from like san francisco to la i mean you have like the owners of the los angeles times uh kind of intermarrying with you know the the uh farming families more from up north and yeah and they fractured and so you have these older families that have i guess they like also like kind of divvied up their inheritances and so they're like their fortunes have gotten kind of smaller you know and they're just like you know sitting on passive income for the most part.

Speaker 2

Whereas Linda and Stuart Resnick, you know, they came in hungry. I mean, they are basically like East Coast Jews and they were hungry for money, man.

They wanted to make a name for themselves.

Speaker 2 And so they were like trying to exploit anything that they could, you know, and so let's not have any anti-Semitic attacks here.

Speaker 3 Yeah, I'll show you.

Speaker 2 As a Jewish person, I can talk about...

Speaker 2 Well, no, no, but they were just like the rumors, you know, encountered, yeah.

Speaker 2 Well, they are like they represent a kind of a newer generation, you know, and where is, I mean, there is actually kind of an interesting, ethnic difference here here because I think a lot of the old, um, a lot of the old farming families are like Anglo, they're Anglos, you know, they're like, they're very, very uptight, very, uh, very white.

Speaker 3 So keep their head down. Yeah, they keep down.

Speaker 2

They keep their head down. They're like, they don't, they don't make waves.

They're, they, they like to stay behind, behind the scenes. And, uh, and, you know, these, yeah, so they're hungry.

Speaker 2 And so, yeah, she used her marketing skills to essentially create a whole a market for pistachios.

Speaker 2 I mean, her whole like innovation, I guess, is she looked at some of these crops like and said, wait a minute, people are selling, I don't know, these things, but they're not branded.

Speaker 2

Like we can create our own brand of pistachios. We can create our own brand of mandarins.

We can create our own brand of a juice that's like branded to our company and that we then push.

Speaker 2 And so it's not like you're, you know, buying just a random orange or a random, you know, pistachio or a random almond.

Speaker 1 It's like, it's like their brand, you know, and so she have the sort of color-coded packaging. You know, if you've been in an airport anywhere in this country, you get a little tube of pistachios.

Speaker 1 They'll tie you over for the flight.

Speaker 2 And so she just used it to create a market. And, you know,

Speaker 2 I think one of the other things about pistachios is that why it's they're kind of a problem.

Speaker 2 I mean, environmentally, I think, is because half or even more than half of the entire crop that's grown in California is exported. Right.

Speaker 2 So what you're doing is actually exporting water, right, by like by another means. So it's not even being, you know, consumed by Americans or in America.

Speaker 2 So it's like being exported as like a very, very expensive snack that has, in a lot of cultures around the world, pistachios are seen as having all these health benefits and stuff like that.

Speaker 2 So they're exporting water by other means in a state that's essentially

Speaker 2 chronically just overtapped to the point where all the rivers in California, it's like no one really knows this, but all the rivers in California are essentially lifeless.

Speaker 2 Like there is no, there are no fish there.

Speaker 2 And the entire ecosystems that these rivers supported have collapsed so there's this like massive uh ongoing extinction event that's been taking place in california and it's largely because of all the water that's being extracted for uh agriculture and and agriculture that isn't even uh necessary for you know to sustain life you know for people in california or people in america it's like it's just frivolous you don't even need to like you don't even need to end it you know you just need to you could cut it back by 10 or 20 percent and a lot of the stresses would come off you know

Speaker 3 maybe i'd go for more than that but it's one of these things it's just a growth-driven mentality and that's all it knows how to do. And they're really killing everything to make these snacks.

Speaker 2 But they're, but they're not the only ones. I mean, they're, in a way, they've made it kind of a problem.

Speaker 2 They've, they, because they're so upfront, because they, they want to be recognized for their business success, they want to be recognized for everything.

Speaker 2 They, they put, they put their names in all the museums, all the, you know, all these cultural institutions in LA. They really want to be recognized, right?

Speaker 2 And so, but the other farmers that are, you know, doing just as like basically doing similar things to them aren't up front.

Speaker 2 they're not like their face isn't plastered everywhere their names aren't plastered everywhere and so in a way the resniks have set themselves up in a massive way you know like so when these fires are happening they're they're the name they're the name that's sort of out there because they're recognizable right and so they're they're almost making themselves like the the the face of everything that's wrong with california agriculture everything that's wrong with like water politics in in california you know they are also probably the biggest you know so let's let not left not let them off the hook they are like i think the biggest i mean they're literally the biggest.

Speaker 1 So, yeah, they are the biggest.

Speaker 3 Yeah, they're not the only ones.

Speaker 1

Well, you mentioned their political power. And now, an interesting thing, Yashin, you mentioned it before.

Sorry, Rowan, you mentioned it. Pistachios heretofore mostly usually come from Iran.

Speaker 1 And now, I recently realized that every pistachio I've ever eaten in my life is an inferior, bastardized version of what should be a proper pistachio, which is what was produced in Iran or much of elsewhere in the world.

Speaker 1 How do the Resniks use their political influence in ways that are unexpected as it relates to U.S. foreign policy? You'd think

Speaker 1 they'd use their political influence to just seize water rights in California, but no, they're heavily invested in a lot of lobbying efforts that are directed against the nation of Iran.

Speaker 1 Could you explain that?

Speaker 3 I've never actually tried

Speaker 3

a real proper Iranian pistachio. I don't think so.

They're dyed red. That's how you can tell.

They have a different process over there.

Speaker 3 But yeah, this is one of the things about the pistachio industry that, I don't know, kind of inspired us to make this movie, which is that, you know, like America didn't used to have a pistachio industry.

Speaker 3

It used to be dominated by Iran. They were the biggest exporter.

And then in like the end of the 70s, start of the 80s, of course, there was the revolution.

Speaker 3 They threw out the U.S.-backed dictator, the Shah,

Speaker 3 and took some Americans hostage. And, you know, relations went rapidly downhill between America and Iran.

Speaker 3 So they put an embargo on all of the products coming into the United States, which included pistachios.

Speaker 3 So now the pistachio industry is very conscious that part of their success, or definitely their market and price point, is dependent on keeping Iranian pistachios out, which probably be cheaper and flood the market.

Speaker 3 You know, whereas at the moment, in American pistachios, partly because it's a wonderful company, it has a monopoly, they sell them only in snack packs, you know, for a ridiculously high price per pound.

Speaker 3 So it's kind of almost distorted the market. Like pistachios are so profitable that,

Speaker 3 you know, like fuck everything else, you know. Like, we don't need vegetables, we don't need fish in California, just pistachios.

Speaker 5 Hot nuts, anybody here want to buy my nuts? Selling nuts,

Speaker 5 hot nuts.

Speaker 1 I've got nuts for sale,

Speaker 5 selling one for five,

Speaker 5

two for ten. If you buy them once, you'll buy them again.

Selling nuts,

Speaker 5 hot nuts, I'm from the peanut man.

Speaker 5 Nuts.

Speaker 1 I mean, like, I mean, this is all sort of like apocalyptic because, I mean, like,

Speaker 1

nuts are fun. They're good to snack on.

But, like, and Yashi put out, like, this is essentially such a frivolous food product.

Speaker 1 Like, nobody really needs pistachios, unlike, for instance, other forms of produce or protein.

Speaker 2 Yeah, I mean, exactly.

Speaker 2 It's like, it's a, it's a, and it's interesting because because they created this market, like Rowan was saying, every time I, every time I go back to California and drive through the Central Valley, it's like I see more and more and more land that used to be dedicated to growing something else basically popping up with trees.

Speaker 2 And because it is like, I think,

Speaker 2 because the amount of, because they're so valuable, it's such a high-value crop, you can get, you know, a really nice return on your investment as a farmer.

Speaker 2 So they've essentially set like the pace of the market and they've convinced everybody to grow these things. So it's like the entire fucking California is like planted with pistachio nuts, man.

Speaker 2 And it's, And it is wild because one of the things that they do, because they are, you know, they are, you know, part of the America. And so America kind of defends their market share.

Speaker 2 So the American trade missions will like go to India and they'd be like, no, no, no, we want you to put high tariffs on Iranian pistachios.

Speaker 2 You know, we want you because they, so they're so by like, and that works for the Resniks, right? And it works for America because America wants to.

Speaker 2 cripple Iran any in any way it can and pistachios are a big export crop for for Iran right that's how it makes sort of brings in foreign currency and things like that for Iran.

Speaker 2 So the Resniks, by trying to increase their market share and by battle their main competitor, Iran, are also

Speaker 2 helping America achieve its foreign policy aims.

Speaker 3 We went down to this pistachio growers convention in Palm Springs at the peak of the drought, and it was this pretty dry little affair.

Speaker 3 But they're talking about water, but number two on the agenda is the Iran nuclear deal and

Speaker 3 how they can lobby against the sun setting of some tariffs. And,

Speaker 3 you know, they were like basically doing a sales pitch there to these pistachio farmers, how much they could spend on lobbying.

Speaker 3 You know, and then in terms of the Resniks, you know, like they, there's articles where they'll talk about how they don't mind stealing market share from Iran, their company representatives, and stuff.

Speaker 3 We don't really know what they're doing,

Speaker 3 but I mean, obviously, the Resniks, they have like a kind of a double-pronged thing. They're,

Speaker 3 you know, they do give a lot of money to like kind of pro-Israel organizations, like Friends of the IDF and, you know, that whole just massive blob of slush funds that kind of feed both anti-Iran and pro-Israel propaganda.

Speaker 3 And, you know, they're also kind of maybe more surprisingly on the board of some think tanks.

Speaker 3 So they've been on the board of this think tank called the Washington Institute Beneries Policy for, you know, over a decade.

Speaker 3 And like the WinAP, Washington Institute is kind of like an APAC spin-off, but it was kind of like APAC like needed to have kind of a neutral neutral seeming information arm.

Speaker 3 So I don't know what these like LA liberals, you know, are on the board of WinEP for, but it's, you know, it's a hardcore neoconservative think tank.

Speaker 3 It's got, you know, all of the Iraq war architects go through there. You know, Dick Cheney is like pulling people out of their first administration during the Bush years.

Speaker 3 So, you know, for some reason, you know, for maybe multiple reasons, they're like...

Speaker 3 they have their you know up to their elbows in American foreign policy and with organizations that are incredibly hostile towards Iran you know, basically to the point of just like workshopping, you know, spitballing ideas to start a war with Iran.

Speaker 3 Like, how can we get this going?

Speaker 2 Yeah, no, I think, I think for them, it's like it is interesting. It is an interesting synergy because they, their, I think, personal politics and their business politics, I think are really

Speaker 2 work together very well and strengthen each other. You know, I mean, they're American Jews and

Speaker 2 like from their even family foundation, just on a personal level, they do give a huge amount of money to Israel.

Speaker 2 And we're talking about just to the IDF, like up to, up to $500,000 a year just to the IDF. They like are funding various cultural institutions in

Speaker 2

Israel. So that's sort of their family foundation.

And then like sort of more on the more of the business side, but then the line between business and personal kind of starts to get erased.

Speaker 2 Yeah, they are on the board of these really, really hawkish think tanks and they're giving money to these Republicans because, you know, the Central Valley in California, the sort of the heart of California is basically dominated still by Republicans.

Speaker 2 California might be a blue state, but all the congressmen in these agricultural regions are Republicans, and they are some of the most kind of looniest, weirdest, dumbest fucking Republicans you can possibly imagine.

Speaker 2 And of course, they're all extremely, you know, I don't know, hawkish on Iran, and, you know, and

Speaker 2 they fund them while, you know, also funding Obama, who was like negotiating the, you know, the nuclear deal with Iran. So they're like working both sides of the issue, you know?

Speaker 2 But clearly, they are like,

Speaker 2 you don't expect, you know, a little pistachio nut to be like so heavily involved in the intrigues of the American empire, you know?

Speaker 2 And yet they like, it's, it's right there, like along with Lockheed Martin,

Speaker 2 you know,

Speaker 2 along with the oil industry, just like basically lobbying and pushing for the most dangerous and, you know,

Speaker 2 kind of horrible foreign policy initiatives America's involved in. Yeah.

Speaker 1 Well, in the wonderful company sort of marketing and sloganeering,

Speaker 1 their tagline is, we can do well by doing good.

Speaker 1 So they seem to be doing quite well. But another aspect to the Resnicks that I thought was interesting is that

Speaker 1 they are hearkening back to an earlier era of American oligarchy. Because one of the things you explore in the film is their sort of weird company town called, what is it,

Speaker 2 Lost Hills? Lost Hills.

Speaker 1 Yes, Lost Hills. Could you talk about your journey to Lost Hills and what you encountered there?

Speaker 2 I don't know, Roe. You want to take that? Because I know you've, you know, we've spent quite a lot of time in Lost Hills, man.

Speaker 2 I really feel for the people who live there. It's a really

Speaker 2 tragic environment, I think. But yeah, go ahead, man.

Speaker 3

Yeah, I mean, yeah, so Lost Hills, I don't know how you describe it. It's a little town at the intersection of two highways on the west side of the valley.

It's a long way from anywhere.

Speaker 3 It's a long way from Bakersfield or Fresno.

Speaker 3 And it probably started out there because there was an oil refinery. So,

Speaker 3 you know, this land out there, it's not the best land, but the Resnicks got it cheap when they were buying up farmland from the oil companies.

Speaker 3 So now you basically have this, you know, this pretty barren little town where half of the people work for the wonderful company

Speaker 3 and it's sort of surrounded by an overlapping grid of orchards and oil fields.

Speaker 3 You know, that sounds like

Speaker 3 a kind of a toxic combination. You're right, you know, because the oil industry and the agriculture out there, you know, intersect in ways you probably wouldn't expect.

Speaker 1

Yeah, I would love to eat an orange grown 10 feet away from a petroleum refinery. Exactly.

We got

Speaker 3 oil wastewater

Speaker 3 and irrigation.

Speaker 3 But yeah, so I mean, like a lot of towns in Central California, there's like terrible water problems locally.

Speaker 3 So they draw their water out of, you know, whereas the orchards get this water that's drawn from the mountains and pumped across the whole state. The towns are stuck with local aquifers.

Speaker 3 So they'll take whatever water they can pump out of the ground. And because there's so much water pumped out of the aquifers, the naturally occurring

Speaker 3 toxins like arsenic concentrate in that water.

Speaker 3 So there's bad things in the water. And then they dump a whole pile of chemicals in it to treat that.

Speaker 3 So the people in these towns are like dealing with this pretty nasty water and nasty chemical treatments. They're dealing with like fumes from the oil refinery.

Speaker 3 They're dealing with agricultural chemicals, which the company says it doesn't drop from planes, but it does.

Speaker 3 It sprays all around the place.

Speaker 3

So you're in this pretty barren little town where a lot of the older workers have already got like thyroids removed. They've had cancers.

They've got all sorts of health problems.

Speaker 3 But then, of course, the wonderful company got some bad public relations. I don't know, back in the 90s, I think, some of their first bad PR.

Speaker 3 And so they decided to drop a whole pile of corporate philanthropy on the town. So they went in and built this.

Speaker 3 you know, wonderful park, like a water park, you know, ironically, like a fucking water park in the middle of town for kids and like a community center. And they did some

Speaker 3 basic things that you would do if you had a tax base in there because i assume the wonderful company doesn't pay a lot of taxes in kern county um so they built streetlights and you know kind of like just pulled the town out of like the desert you know basically from being a dirt street kind of town into like a town with one boulevard and some streetlights and a park uh but you know of course they didn't fix any of the problems about with the water yeah it's a pretty bleak environment man i mean because it's like you just yeah you have essentially a corporate run town like like the stuff that you'd you know you'd you'd hear about like a mining town or something that you know basically all the workers live in this town that's owned by the mining company they're paid in script you know they have to shop at the company store

Speaker 2 well it's true because everyone everyone has pistachios in their houses and stuff you know like and and it's and it's like and it's very bleak man because you have essentially these sort of uh

Speaker 2 kind of several generations of immigrants, you know, usually from Mexico or from sort of Central America. And

Speaker 2 they live in this world where they're just being slowly poisoned to death, you know, by, again, like what Rowan was saying, by the fact that the oil industry is right there.

Speaker 2 So you have like orchards, you know, and like you'll have pistachio orchards like

Speaker 2

surrounding, you know, these pumps that are actively pumping oil out of the ground. I mean, they're like, they actually are like integrated completely.

You'll have sort of produce, right?

Speaker 2 Things that you eat like right next to on top on it being grown in an oil field,

Speaker 2 to put it simply. And so you have these people who live in this world and they're being poisoned to death.

Speaker 2 And like the Resniks, you know, just like basically threw some millions of dollars down to create like a little playground for the kids and like create a little community center.

Speaker 2 And they bring in all like

Speaker 3 programs, you know, so they try to feed the workers healthy food, kind of like LA fad food and the cafeterias and do exercise programs.

Speaker 3 But then they'll go on like a video and they'll talk about how it makes their workforce more productive. They're pretty naked and they're like,

Speaker 3 you know, self.

Speaker 3 It creates a funny dynamic in these towns because it's basically a split between the people that get on the company track.

Speaker 3 Like, you know, because I think still for a fair number of the workers, they come there and they're like, well, you make like slightly more than minimum wage as a pistachio harvest guy.

Speaker 3 And, you know, you can get your kid a scholarship in the charter school, you know, run by the Wonderful Company, the corporate-branded charter school.

Speaker 3 So if you've got good English and you're like looking for like a middle management career at the Wonderful Company, you know, you think they're great.

Speaker 3 But I don't don't know, the reality is the company is just sucking that area and the people completely dry.

Speaker 2 And the kids, man, I mean, I don't know, we haven't done a systemic study, but like, you know, some of the kids clearly have developmental problems because they've spent their entire lives and were, you know, basically carried to term in an extremely toxic environment, you know?

Speaker 2 And so like you have this kind of pathway to success, I guess, for people, you know, like you get into the charter school.

Speaker 2 If your kid does really well, they might get like a corporate scholarship to like one of the local universities but that's all predicated on the fact that if if the parents have to remain workers at the company and workers of good standing so they shouldn't be agitating for any kind of union uh and all this stuff you so like it's all very tight in it's very it's very bleak man and because they are you know because they're so supported by like the liberal establishment in los angeles i mean they're um you know they'll bring out like an la times reporter or a new york times reporter um and like show them the the park they that they put there, you know, and they'll like be presented as these almost like liberal saviors, like these, that they're actually helping these people, right, live a better life rather than like sucking the life out of them and poisoning them.

Speaker 2 And it's it's a really bleak because it gives you this insight into, I don't know, the liberal flank of American capitalism. And it doesn't really differ much from

Speaker 2 the rightist flank of liber American colours.

Speaker 1 You can treat the cancers that your job has given you with coupons for Erewhon smoothies, which are quite good.

Speaker 2 Yeah, yeah, yeah, yeah, exactly. Well, you know, it's like you got to be like, you know, doing, I don't know,

Speaker 2 meeting quotas for like 10 years or something to get an arrow on.

Speaker 1 You can get one smoothie, yeah.

Speaker 2 I mean, come on, man, that stuff is expensive, you know?

Speaker 2 Yeah. So

Speaker 2 it's bleak to just be there. I don't know, it just puts you like all the liberal like facades that is,

Speaker 2 all the facades that are slapped under this liberal capitalism, I mean, really fall apart, fall away when you're out there, you know?

Speaker 2

Because you just see it at like the savage core of it. It's just like they just really, nothing has really changed in America, you know, since the Robert Barron days.

Yeah.

Speaker 1 So, like, Yasha, like, I said, like, you've been, you've been covering water and use in California and like the Central Valley in California for a while.

Speaker 1 I mean, that's how I first started reading your stuff.

Speaker 1 But in the process of doing this documentary, Pistachio Boys, for you and Rowan, was there anything that you found while you were making this movie that surprised you or that like changed like your perception of how power works in California?

Speaker 2 Oh, that's a good question.

Speaker 1 Hmm.

Speaker 2 Rowan, do you have a answer that?

Speaker 3 Yasha was already jaded, you know, but I come from New Zealand, so I'm like definitely ripe for some shocking. I mean, I think the oil thing was pretty surprising.

Speaker 3 I mean, just how captured Central California is by the oil industry.

Speaker 3 You know, you think of California as this environmental, you know, bastion of progress.

Speaker 3 But, you know, the reality is they've got these oil companies just dumping waste into open pits that are like leaching into the water system out there and even being recycled into agricultural water.

Speaker 3 And

Speaker 3 the state basically enables it.

Speaker 3

Even the Democratic governors. So that shocked me a little bit.

I mean, I'd already read about the Resnicks from Yasha's reporting. So I knew a little bit about that.

Speaker 2 I'd say for me, I'd say for me,

Speaker 2 probably

Speaker 2 It didn't really open up any new vistas of how horrible America is or how horrible California is.

Speaker 2 I enjoyed just doing a documentary because it gave me a lot more time to hang out and like talk to people.

Speaker 2 You know, because when I was doing a lot of reporting on my own, like kind of going in solo and I just didn't have the resources when I was doing my reporting to really talk to people and hang out in these little towns, you know, because we hung out in this one town called Porterville and like we just got into this weird like drama at the center of this town between like this the guy who owned you know i don't know like a concrete plant and some orchards and like there's like some, he's like, you basically, I don't know, he didn't steal

Speaker 2 this other guy's wife, but like, it's all tied to like this feud over water.

Speaker 1 Do you get it?

Speaker 1 How are wife rights appropriated in California?

Speaker 2 Well, the wife goes with the money.

Speaker 2 It's like, it's in pistachios, I think. It's like they put them on a big scale and the guy with the biggest nuts, you know, wins.

Speaker 2 But, you know, it's like, I think that was the most kind of bleak and kind of, but also interesting because there are real people. and and like um

Speaker 2 and I know and then connected to that I think is like a more of a kind of a political realization that like even you know like the people in Lost Hills who are essentially being worked to death and poisoned by the Resnicks still like hold the Resniks in like good regard you know because they see them as like compared to what how how bad other

Speaker 2 like employers can be or their experience you know and other and with other employers like they're like decent they're okay okay, you know, they're not like the worst, you know?

Speaker 2 And I think that's, there's some perks that they give.

Speaker 2 And so I think that's sort of like really floored me, you know, and it kind of goes to this idea of like, what's your political consciousness, you know?

Speaker 2 So these workers, you know, who are being worked to death

Speaker 2 by this oligarch, poisoned on every level from the water they drink to the air they breathe, you know?

Speaker 2 Yet like they still like say, oh, they're all right. They're not too bad, you know?

Speaker 2 And that's really, I think, did fuck me up a little bit because I don't really know what to say you know about that

Speaker 1 so i mean like in trying to like sort of uh think think about the this entire issue like obviously uh water next to you know breathing is probably you know just about one of the most foundational things for maintaining human life anywhere california you know what we sketched out what you guys have sketched out here is that like the way it's used in california seems to be uh almost like designed to to destroy human life rather than sustain it.

Speaker 1 So like using using California California as but one example, like, and I'm not asking like to fix the problems of the world, but like

Speaker 1 going forward in like the next century or so, like if American society wanted to utilize its water resources in a way that would sustain human life for another 100 years or so rather than doom it,

Speaker 1 what would that look like?

Speaker 1 What would a state that was interested in marshaling its natural resources for the benefit of the people who live in that state and like and their health, either whether it's mitigating disasters caused by fire or drinking preparing food washing like what would how would water use be different in a in a better more sane society

Speaker 2 I could take a crack at this question and then maybe you can add something Rowan I mean look

Speaker 2 The way that decisions are made right now in America about the way that water is distributed and the way that anything happens in California is just through profit. Like it's just straight up.

Speaker 2

You know, it's like, how can you make money off something? That's it. There's just like the profit motive.

That's the only thing that's in operation. Right.

Speaker 2 And so you have to basically take that out of considerations.

Speaker 2 If you want to have a society that is about human thriving, that is about retaining some semblance of natural life on this planet and like having people enjoy natural life, you know, and not living on a totally denuded, destroyed, like fucking nub of

Speaker 2 a planet, you know, you have to think about like maximizing like the use of resources for public for the public benefit right so that means that you're probably not going to be building homes using pumping water hundreds of miles you know and and and building suburbs you know that without end or homes in in in mountains and hills where that are naturally fire prone you know like like in los angeles that you know

Speaker 2 routinely go up in flames and like then you know cause all sorts of destruction and and human suffering you're probably gonna you know have to decide as society

Speaker 2 how to maximize water use,

Speaker 2 because water needs to be used to farm, right? So, what are the things that should be farmed? What are the crops that should be grown?

Speaker 2 Who should they profit? What kind of crops should they be? Who can extract value out of it?

Speaker 2 It should be a kind of a holistic

Speaker 2 conversation and discussion

Speaker 2 about it, right? And that's just, we're so far away from that, like that it's, you know,

Speaker 2

people aren't even aware that the problem exists exists at this point. You know, we're not even at a point of like discussing what to do.

It's most people aren't even aware that there is a problem.

Speaker 2 And just to put a number out there that I think is important, 80% of water that's used in California goes to agriculture, right? So if you get rid of

Speaker 2 all, you know, human life in California, like

Speaker 2 you zap LA, you zap San Francisco, you zap all the suburbs, and there are no more people there, You only like will achieve like a 15, 20% reduction in water use, right?

Speaker 2 So like all the low-flush toilets and things like that, like that's like, that's like a percentage of a percentage of a percentage point.

Speaker 2 So 80% of the water goes to agriculture, and a lot of that stuff goes to like low-value crops like alfalfa that is then grown to feed cows, that produce, you know, dairy, you know, milk.

Speaker 2 or to, you know, to, that, that produce meat. So you want to, or, or a lot of that water goes to, you know, to grow pistachios and things like that.

Speaker 2 So you, as a society, you're going to have to figure out like, okay, what are the things that we're going to grow?

Speaker 2 In what amount are we going to grow it? What are we going to use this precious resource for? And how are we going to use it? Right. So that's like allocation of resources is like key.

Speaker 2 And it's just, and right now it just happens in a very monopolistic, profit-driven way that people have no control over.

Speaker 1 And I, you know, ideally, like, the state would be the one deciding in some sort of democratic process, like how you allocate those precious resources. But

Speaker 1 we have a state that's fully captured just by profit. So decisions can't be made in terms of what will maximize human potential in life.

Speaker 1 It's what will maximize the bank accounts of the Resnick family. Basically,

Speaker 3 we have like, we use the blob as a metaphor in the film because it's kind of like the market momentum, you know, just around greed and overdevelopment is.

Speaker 3 the only thing driving anything in California.

Speaker 3 I mean, I'd like to think that a democratic process could allocate things more effectively.

Speaker 3 You know, that's an optimistic view of society.

Speaker 3

Maybe they would just keep plundering it because it's out of sight. You know, like people don't need fish.

They can just have fish on their screensaver or something, you know, but

Speaker 3 I mean, yeah, I don't know. Yeah, I don't know what it takes.

Speaker 2 We live in a really

Speaker 2 kind of an incredible moment, man. I mean, like, you have, you know, like access to, you know, the most amount of information, you know, possible in human history, right?

Speaker 2 And then all that that sort of gets boiled down to is like people

Speaker 2 screaming at each other about woke, woke, fucking this, lesbian firefighters, you know, like, and it's like, that's the level of conversation we're at. And it's like,

Speaker 2 or just even understanding or even like the level of interaction that people have with

Speaker 2 their lived reality.

Speaker 2 And so, yeah, I don't think that the systems that are in place now, the media systems, the political systems are capable of having that kind of, you know, are capable of actually having,

Speaker 2 I don't know, it's what is it, like the discussion, the debate, the process by which these things get hashed out, because I don't think we can even agree on what it means.

Speaker 2 What does human thriving mean? What does it mean?

Speaker 2 It means different things to a lot of different people, you know? And so I think even though these terms are contested, it are like not even clear. And so.

Speaker 1 I don't know.

Speaker 1 I think a good place to start with what does human thriving mean would be like the most amount of drinkable water from the number of people that currently exist.

Speaker 1 I think that would be like a good place to start. Yeah,

Speaker 2 but it can be.

Speaker 3 You know, like water privatization is like, because we've grappled with this a lot, people think of like, I think a very like a binary idea of water privatization.

Speaker 3 It's like, well, you know, when the water is privatized, there's going to be some robot out of like a, you know, Blomkamp film.

Speaker 3 You'll go down to get you a cup of water to keep you alive for the day and it'll, you know, shoot you in the knee or something if you don't stand in line.

Speaker 3

And, you know, if you don't have a dollar, you're going to die. You know, and anything less than that is not real water privatization.

But, you know, I mean,

Speaker 3 the reality in California is it's this kind of like behind-the-scenes privatization where, you know, like they're probably a long way away from stopping you to have anything to drink.

Speaker 3 But we have sort of seen it already in little towns like Porterville, where there was a crisis and suddenly there was a shortage, and people realized, or maybe didn't even really realize, but the local industry took all the water.

Speaker 3

And I think, you know, California could have a moment like that. I don't know if the fires are that.

I think people are kind of thinking it's that and the fires.

Speaker 3 California could have a moment where they're like, fuck, we need some water. You know, LA is short of water for drinking.

Speaker 3 And suddenly, wonderful company's like, well, we own that.

Speaker 3 And of course, they believe in capitalism.

Speaker 3 They own it fair and square. They're not giving it up.

Speaker 2 Yeah, I mean, just to add, I want to say something because, like, look, the thing about water is that

Speaker 2 water is at the root of all life in California. I'm in upstate New York, and it's water is also,

Speaker 2 I'm in upstate New York right now, but water is also at the root of all life, but there's like water everywhere.

Speaker 2 You can't like you, you try to get rid of water, it's like it flows up from the freaking.

Speaker 1 You can't say many good things about New York State, but one of the good things you can say about New York State is that they're very careful about development near their watersheds.

Speaker 1 Yeah, yeah, yeah, yeah. New York City has good tap water.

Speaker 2

Exactly. And there's a lot of water, abundant water around.

But in California, it's the same is true, but water is not around. And so if you are like the Resniks,

Speaker 2 and you are able to put yourself as a middleman

Speaker 2

in this water pipe, which is essentially what they are. They control this water bank and water that goes in there, they can do with it as they like.

They can use it for their farms.

Speaker 2 They can use it sort of to crush their competitors, basically to give, to undercut their competitors by giving people subsidized water who are like on their side, which they have done.

Speaker 2 Or you can, if like, let's say farming is no longer valuable, you can just turn around and sell that water to Los Angeles or sell that water to some other city. And so they are like

Speaker 2 they're these water barons in a way, because right now they're farming because that's what brings in the most amount of money for them.

Speaker 2 But if, for instance, the price of water grows to the point where it's just easier for them to just sell it, right? And just to be a middleman, they can do that too.

Speaker 3 And then that's the thing. That's interesting is when they start selling the water back to the state for environmental uses.

Speaker 3 So, you know, they've made millions of dollars selling water back to the rivers in Northern California.

Speaker 3 So when there's not not enough water to keep the fish alive and the state's like, wow, the flows are low. They'll go and buy some water off the Resniks.

Speaker 3

And it's not even clear if they actually move the water. It's just kind of like this paper deal.

But now

Speaker 3 they're paying the Resniks not to kill the fish, basically.

Speaker 1 Boy, selling water to a river.

Speaker 1

That sums up. That's a great summation of capitalism in the 21st century.

You can make money doing anything.

Speaker 2 No,

Speaker 2 California is a really, you know, it's in an innovative place like that.

Speaker 3 That's the thing about all these big systems they were developed in the new deal and everybody tends to have a pretty rosy idea of the new deal because it was you know like maybe a rosy period in American history but um it was that kind of techno utopian idea of development and this idea of humans basically conquering nature you know and I think a lot of people are starting to look at these big dams that have been built in California and realize the problems around them.

Speaker 3 You know, there's like one dam reclamation project

Speaker 2 that's happened where they're trying to bring a river back to life, but it's like yeah, but you know, that whole thing is, it's great yeah they've taken down a dam but the only reason it was taken it's taken down is because the the company that owned it like it was like it cost them more it cost more for them to maintain it uh yeah so it's like no one's really i i actually kind of disagree no one no one's really um for

Speaker 2 in a serious way talking about like oh what should we do do we need to like dam every single fucking river in california um so we can grow pistachios it's like it's not a conversation it's not even a you know it's not in on people's minds Yeah, yeah.

Speaker 3 And like going back to the New Deal, it wasn't just this benevolent idea. It really was driven by industry.

Speaker 3 And it came at a time when the farmers basically had a huge pressure to bail themselves out because they had already drained all the groundwater.

Speaker 3 So, you know, the New Deal deal side of things with industry

Speaker 3 shouldn't be forgotten.

Speaker 2 Yeah, we kind of poo-poo the New Deal a little bit in our documentary, you know, because there are aspects to the New Deal that are actually,

Speaker 2 in hindsight, very destructive, you know, and kind of driven by corporate um lobbying and sort of the corporate sort of uh behind the scenes corporate needs uh to plunder california for its water supplies and yeah it's kind of an interesting part of the story that even i didn't really know and you know until we really got into the history of it all right well i think we should uh leave it there for today but the the film is pistachio wars that's uh available now at uh pistachiobars.com correct That's right.

Speaker 3 You can go there. You'll click through to the VOD thing.

Speaker 3 Get it. Special advanced release.

Speaker 1 All right, we will have the link in the episode description. Rowan, Yasha, thanks for your time and thanks for coming on and talking about water in California.

Speaker 2 No, it's a pleasure. Thank you.

Speaker 3 Yeah, thanks a lot, man.

Speaker 1

Cheers, guys. That does it for us today.

Till next time, everybody, bye-bye.

Speaker 6 All day I face the barren waste without the taste of water.

Speaker 6 Old Anne and I, with throats turned dry, and souls that cry

Speaker 6 for water

Speaker 6 Cool,

Speaker 6 clear

Speaker 6 water

Speaker 6 Dan, can you see that big green tree Where the water's running free And it's waiting there for you and me