#52 Lenny

Press play and read along

Transcript

Speaker 1 Do you wear shoes with shoelaces?

Speaker 1 Or you wear Velcro?

Speaker 2 Do you come up with these questions by yourself?

Speaker 1

No, I have a writer's room. No, I'm just curious.

I remember you used to like Velcro. You said that anybody who is foolish enough to have to stoop down and tie their shoelaces deserves what they get.

Speaker 1 That shoelaces get covered in urine and bile, and that Velcro is the fabric of the future. That's That's what you'd always say.

Speaker 1 You have shoes with shoelaces, right? I have shoes with shoelaces, yes. Do you always double-knot them? No, you don't.

Speaker 2 Any other compelling questions, Johnny, that you have?

Speaker 1 If you showed up to a bowling alley with a watermelon, you think they'd let you bowl with them?

Speaker 1 I'm Jonathan Goldstein, and this is Heavyweight.

Speaker 1 Today's episode, Lenny.

Speaker 1 Right after the break.

Speaker 4 This is an iHeart podcast.

Speaker 5 In today's super competitive business environment, the edge goes to those who push harder, move faster, and level up every tool in their arsenal. T-Mobile knows all about that.

Speaker 5 They're now the best network, according to the experts at OCLA Speed Test, and they're using that network to launch SuperMobile, the first and only business plan to combine intelligent performance, built-in security, and seamless satellite coverage.

Speaker 5

That's your business, Supercharged. Learn more at supermobile.com.

Seamless coverage with compatible devices in most outdoor areas in the U.S. where you can see the sky.

Speaker 5 Best network based on analysis by UCLA of Speed Test Intelligence Data 1H 2025.

Speaker 6

There's more to San Francisco with the Chronicle. There's more food for thought, more thought for food.

There's more data insights to help with those day-to-day choices.

Speaker 7 There's more to the weather than whether it's going to rain.

Speaker 6 And with our arts and entertainment coverage, You won't just get out more, you'll get more out of it. At the Chronicle, knowing more more about San Francisco is our passion.

Speaker 6 Discover more at sfchronicle.com.

Speaker 4

You've probably heard me say this. Connection is one of the biggest keys to happiness.

And one of my favorite ways to build that? Scruffy hospitality.

Speaker 4

Inviting people over even when things aren't perfect. Because just being together, laughing, chatting, cooking, makes you feel good.

That's why I love Bosch.

Speaker 4 Bosch fridges with VitaFresh technology keep ingredients fresher longer, so you're always ready ready to whip up a meal and share a special moment.

Speaker 4 Fresh foods show you care and it shows the people you love that they matter. Learn more, visit Bosch Homeus.com

Speaker 1 Back when I was a kid, I often carried around a tape recorder. An outstretched mic created a buffer between me and the world.

Speaker 1

Recording was my way of managing life, and so I recorded everything. My parents' arguments.

She's good natured.

Speaker 3 There's a difference between super and good natured.

Speaker 1 Their phone calls.

Speaker 3 And I'm telling you it's rock and fish, but fuck.

Speaker 1 My mom pretending to audition for soap operas.

Speaker 9 Amanda, darling, how are you today?

Speaker 1 Mostly, though, I recorded myself. I made radio plays.

Speaker 9 Wittstein Productions present

Speaker 1 the adventures of Nedley!

Speaker 1 With no one to share in my love for a medium DOA since the Truman administration, I put on the plays alone, all the voices performed by me for an audience of zero.

Speaker 11 Our story opens up where Nedley is about to get off.

Speaker 11 What a lousy day!

Speaker 11 That's our Nedley.

Speaker 1 Nedley was an 11-year-old Spitfire who did as he pleased. Since I myself was an 11-year-old rule-following nerd, Nedley was my id.

Speaker 11 Here comes Boom Boom.

Speaker 9 She's my dream girl.

Speaker 9 Hi, Nedley.

Speaker 9 I'm Boom Boom Boom.

Speaker 1 And the whole psychodrama played out as a one-man show.

Speaker 11

This movie was directed by Jonathan Goldstein, screenplay by Jonathan Goldstein. All voices in it are done by Jonathan Goldstein.

This is a Jonathan Goldstein production.

Speaker 1 It was all just me and my microphone. Until the day Lenny came along.

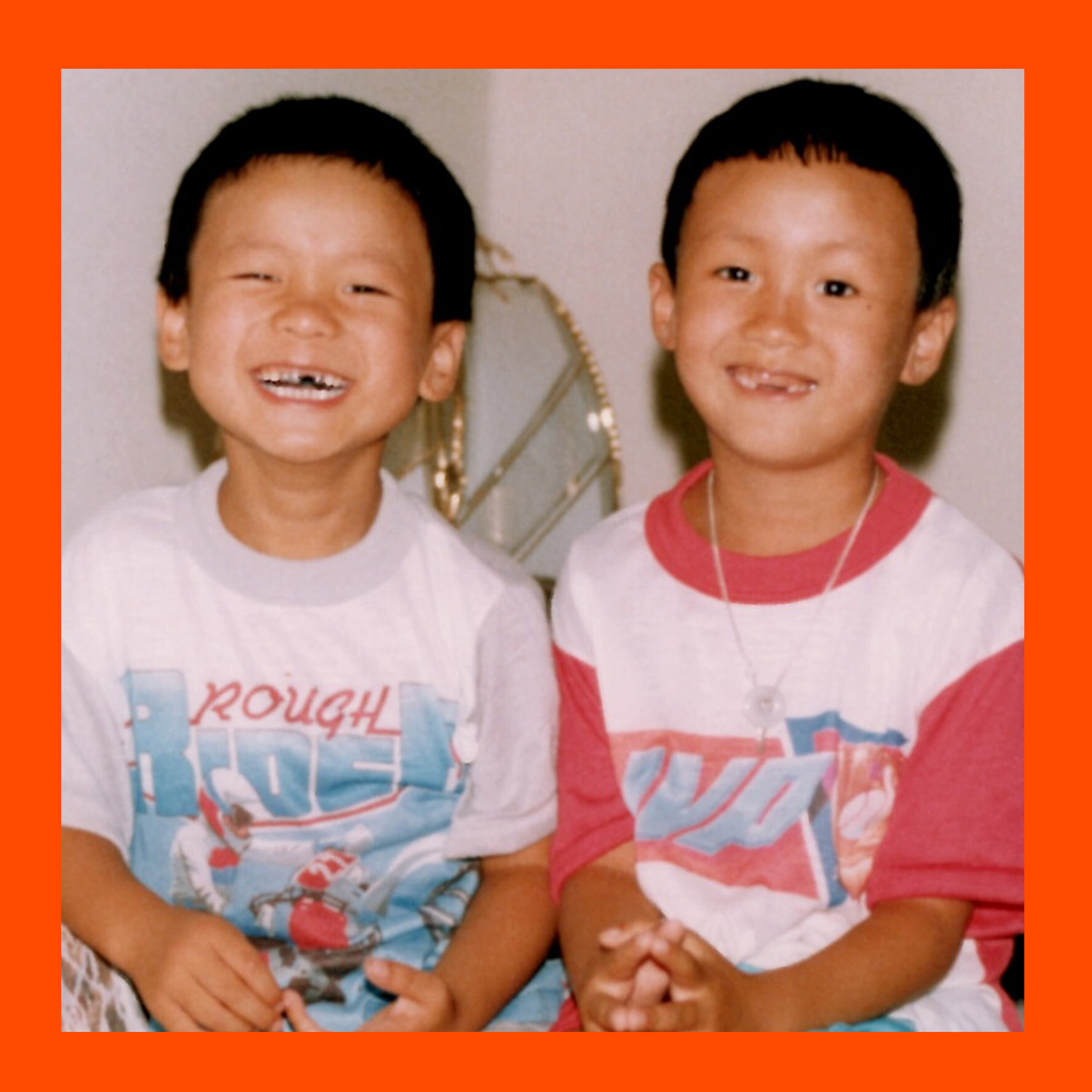

Speaker 1 I was 12 years old when we were first introduced at a birthday party. Immediately, Lenny asked me what blood type I was.

Speaker 1 Oh, I said uncertainly.

Speaker 1 Me too, he shouted, genuinely excited to find some small thing we shared.

Speaker 1 I was an aloof kid, but was quickly won over by Lenny's goodness, and the fact our mothers were already best friends made our best friendship feel faded.

Speaker 1

Plus, that Lenny proved as obsessive about recording as I was sealed the deal. The weekends revolved around our recording radio plays.

Lenny and I would sleep in the same fold-out in his parents' den.

Speaker 1 His dad, Izzy, a large man with a thick Polish accent, would make us breakfast in just his underwear, his undershirt tucked into his jockeys like it was some style imported from the old country.

Speaker 1 One time, trying to explain to Izzy how I liked my eggs and having no success with fried, I described two suns in a cloud. Lenny loved that so much that he started ordering his eggs that way too.

Speaker 1 Two Sons in a Cloud.

Speaker 1 After breakfast, we'd head to Lenny's bedroom, shut the door, and record all morning.

Speaker 1 We were a gang of two. Gold and Lennox presents.

Speaker 1 The Lennox was from Lenny, the Gold from Gouldstein. For the first time, I no longer felt alone.

Speaker 1 Together, Lenny and I recorded prank phone calls, our parents' dinner parties, and we made radio play after radio play, creating characters like Flip and Will, two burned-out radio DJs.

Speaker 10 Flip is taking you to Will, okay? Will.

Speaker 1 As a part of the Flip and Will radio show, we did live phone outs to our quote-unquote listeners.

Speaker 1 In the 80s, dialing a phone was so arduous, it's surprising people even bothered. But without driver's licenses or money, Lenny and I made the effort.

Speaker 1 The phone brought us a sense of freedom and adventure.

Speaker 10 Okay, it's me.

Speaker 10 It's me.

Speaker 10 Hello, what would you do if you had a million dollars? This is a television survey.

Speaker 10 Why, thank you. This station needs it.

Speaker 9 Bye.

Speaker 9 The Cold War is not over.

Speaker 13 It never was.

Speaker 1 This is Lenny now, age 52.

Speaker 13 John, what is not understandable about this?

Speaker 13 Because I'm getting frustrated now.

Speaker 1

I'm in Minnesota and Lenny is in Canada. We haven't spoken in nine years.

And at the moment, for some reason, we're discussing Russia's role in Ukraine. Well?

Speaker 1

In our late teens, Lenny and I began to have less and less in common, and we drifted apart. Our first conversation in almost a decade is not going well.

I mean, I'm not sure that I fully get it.

Speaker 1 You mean that... It's really simple.

Speaker 13 I mean, it's not that complicated.

Speaker 14 It's not.

Speaker 5 Yeah.

Speaker 13 We destroyed communism using their communism. Now they're destroying capitalism using our capitalism.

Speaker 1 With the way he kept his arms crossed and his posture erect, that evening Lenny had something of the dictator about him.

Speaker 1 He was living in the bachelor's apartment in his parents' basement in Chomity Laval, a suburb we grew up in just outside of Montreal.

Speaker 1 Lenny drove a school bus for Orthodox Jews and said the Hasidim had nicknamed him the surgeon because of how he zipped through narrow streets with such precision.

Speaker 1 At the end of the meal, Lenny asked if I wanted to go outside and smoke a joint, a for old time's sake kind of thing.

Speaker 1 The idea of smoking a joint outside a suburban strip mall restaurant while our aged parents waited inside was unappealing, so I said no.

Speaker 1 At least stand outside with me, Lenny said, and keep me company. But I dug my heels in, and Lenny grew angry.

Speaker 1 We parted on bad terms that evening, almost 10 years ago, and that was the last time I saw Lenny or thought too hard about him. Until now.

Speaker 1 The reason Lenny and I are speaking right now is because he has only months to live.

Speaker 1 Lenny is dying of pancreatic cancer and is undergoing chemotherapy and radiation. He's recently gone through 11 hours of surgery to keep the cancer from spreading, but it was no use.

Speaker 1 Even though that first conversation went poorly, I continue to spend my evenings talking to Lenny.

Speaker 1 Because somewhere in the back of my mind is the memory of the kid from my childhood, the kid who stayed by my side tending to my adult-sized depression.

Speaker 1 In the darkest hours of my teens, I remember days and nights spent in Lenny's bedroom, just lying in his bed under the black bulb of his light fixture, listening to Pink Floyd and Iron Maiden, too scared to face the world.

Speaker 1 Back then, Lenny would reassure me, telling me to think all the bad thoughts I could, to get them out of my system, to exhaust them, so that eventually I'd only be left with the good ones.

Speaker 1 Being with Lenny was one of the few places where I felt safe.

Speaker 1 And so, I call him again and again.

Speaker 1 Hey, Lenny, how are you doing?

Speaker 15 Uh, same shit.

Speaker 1 Yeah.

Speaker 1 Our conversations usually occur at night, with Lenny still in his parents' basement, the same basement where we spent our childhoods, and me wandering the silent streets of my Midwestern neighborhood.

Speaker 1

During these phone chats, I never know what to say. I struggle to find common ground, but always come up short.

When I bring up old mutual friends, Lenny speaks of them resentfully.

Speaker 1

With jobs, it's the same. The idiots at the trucking firm, the anti-Semites at the refrigeration company.

On the rare occasion I raise something personal about myself, it gets no traction.

Speaker 1 When I tell him how I'm now a father of a five-year-old, Lenny, a bachelor, says that people who have kids only do it for ego reasons.

Speaker 1 Mostly, we stick to the subject of Lenny's pain, which is brutal. He can't eat without pain, stand, or even lie down without pain.

Speaker 1

Sometimes he'll put the phone down and I'll listen to him as he howls from the bathroom. There are drugs, some prescribed and some not, but no matter there's always pain.

And anger at the pain.

Speaker 1 And anger at, what seems like,

Speaker 1 me.

Speaker 1

On most nights after a typical conversation, I come home and say to my wife Emily that maybe this is a bad idea. We drifted apart for a reason, I say.

We're strangers.

Speaker 1 And yet, even though Lenny doesn't seem to even want to talk to me, we continue to talk night after night. I'm beginning to get the impression that maybe he has no one else.

Speaker 1

You'll find if I eat while we're talking about it. No, no, no, of course not.

Well, wish me luck. Lenny says he wants to leave something behind, and so we record, just like we did when we were kids.

Speaker 1 Back then, we performed different characters. Now, ostensibly, we're just ourselves.

Speaker 13 rice.

Speaker 1 Great. And how's your sleep been?

Speaker 14 I sleep like shit. What do you think? I have to take a med every two hours.

Speaker 16 A horrible life.

Speaker 13 When you spend your life vainly,

Speaker 13 the universe likes to punish you.

Speaker 13 All the anger, all the hatred.

Speaker 14 What do you think? You could get away with it.

Speaker 1 Lenny is no longer the sweet, lonely kid who told me not to swat the house fly in his bedroom because he was his pet.

Speaker 1 The boy with whom I'd been so close that I'd run my hands through his thick black hair as though it were my own.

Speaker 1 Smooshing it up into the air, I pretended I'd invented the latest in men's hairstyles, the Beethoven.

Speaker 1 That Lenny seems to be long gone.

Speaker 1 Even though Lenny and I weren't in touch, over the years when I'd ask after him, my mother would always say the same thing. Lenny and his parents were fighting like cats and dogs.

Speaker 1

Lenny's father died about a year ago. Now it's just him and his mom.

Do you

Speaker 1 see your

Speaker 1 mother every day?

Speaker 13 Unfortunately, I

Speaker 13 make an attempt to treat her like a human being.

Speaker 14 And every day she disappoints me. She's gross, my mother.

Speaker 14 My father, too, he was gross.

Speaker 1 Too gross to be.

Speaker 1 You loved him. You loved your dad.

Speaker 13 Yeah, I did, but he was a gross man.

Speaker 14 Always did everything that makes his life easier.

Speaker 14 My life harder.

Speaker 1 Lenny's parents had had another son before him, but because of profound mental and physical disabilities, he was institutionalized. After that, they adopted Lenny.

Speaker 1 Both Lenny and I were raised by parents who saw screaming and hitting as the solution to all of life's child-rearing dilemmas. But from Lenny's perspective, worse than that was the neglect.

Speaker 1 Lenny's dad worked a lot, and his mom always seemed to have more time for her friends than for him. It's something Lenny still can't let go of.

Speaker 13 It's called normal responsibility.

Speaker 13 You know what I mean? All my friends got it.

Speaker 14 How come I didn't?

Speaker 1 Yeah.

Speaker 13 Well, what's so unspecial about me that I get the shitty fucking neglect?

Speaker 14 Yeah.

Speaker 14

I did my best. That's my favorite wine.

I did my best.

Speaker 14 You know, if that's the best, maybe you shouldn't have bothered.

Speaker 1 Yeah. That's your best.

Speaker 13 I'll tell you the truth.

Speaker 14 I'm looking forward to having that one last week, knowing that it's finally done, and I can just like

Speaker 14 rest.

Speaker 16 Because it's been a bitch. This life has been a bitch.

Speaker 14 And it's supposed to be because the people have been a bitch. And they remain bitches.

Speaker 1 What does one owe a childhood friend? Especially when that friend seems to have changed so much.

Speaker 1 Over the course of our phone calls, a question that keeps kicking around in the back of my mind is whether all of Lenny's anger has somehow eaten up the goodness.

Speaker 1 I continue to phone Lenny over the next couple months in hopes of seeing it, feeling that goodness again.

Speaker 1 And so we talk about the sex ed books at the YMHA library, watching the love boat on Saturday nights when his parents were out with my parents, raiding his mom's freezer for TV dinners while playing ColecoVision.

Speaker 1 Mostly though, I just listen and try to be there. And over time, Lenny grows softer with me, and I grow less afraid of offending him, afraid of offending a dying man.

Speaker 1 And then one night, I receive a message. Listening to it now, I'm struck by how much Lenny's voice had mellowed since our first conversations.

Speaker 1 Instead of Jonathan or John, Lenny calls me Johnny, just like he did when we were kids, like he did when we were best friends.

Speaker 16 Hi, Johnny. I'm sorry to call you directly like this without signaling or anything, but

Speaker 16 it's been a development and I needed to talk to you

Speaker 16 as soon as you can.

Speaker 15 Yeah, hey, John, is it too late?

Speaker 5 No, no, no, it's okay. How are you?

Speaker 15 Not well, John. You know, it's hard to tell you anything else.

Speaker 1 I'm sorry.

Speaker 1 What's going on?

Speaker 15 I'm just, I'm weak. I'm going to go into palliative care.

Speaker 1 Okay.

Speaker 15 There's no other recourse.

Speaker 1 Yeah.

Speaker 15 It's getting harder and harder to function at home.

Speaker 1 Yeah.

Speaker 15 Because I'm not too good with pain, John.

Speaker 1 Well, you've been dealing with so much of it.

Speaker 15 No, I mean, my whole life, I've never been good with pain.

Speaker 15 I'm a whiner, Mois.

Speaker 15 I'm just a big ones.

Speaker 15 It's funny, through everything, the pain's still there.

Speaker 15 Pain never ends.

Speaker 15 Even with the drugs, yeah.

Speaker 15 That's that bad, John.

Speaker 15 I don't foresee getting better.

Speaker 15 If I suddenly disappear or, you know, I can't talk to you,

Speaker 15 no, I'm probably like, you know, gone.

Speaker 15 I had my last drive yesterday. I drove around Laval.

Speaker 15 Yeah, just like one last highway ride.

Speaker 15

It's not a huge deal. I did a lot of driving in my time.

I have plenty to remember.

Speaker 15 I'm dying anyway. I have bigger things to think about.

Speaker 1 What do you find yourself thinking about?

Speaker 15 Nothing.

Speaker 15 I lived as well as I could in my capacity.

Speaker 15 Had good experiences at least.

Speaker 1 You know,

Speaker 15 wasn't the best life well lived, but it wasn't the worst either.

Speaker 15 Could have been worse.

Speaker 15 That's the legacy of my life. Could have been worse.

Speaker 15 Just got

Speaker 15 I just want to enjoy looking at the sky, looking at things, you know, yeah,

Speaker 15 revealing it to be my life while I still want.

Speaker 15 I remember the last lady, she was scary.

Speaker 1 Who's this?

Speaker 15 The lost lady witch. She's a little pudgy.

Speaker 15 Remember?

Speaker 1 Lenny would sometimes drift into delusions, imaginary flights that would weave throughout our conversation.

Speaker 1 But other times, the delusions were mixed up with childhood memories, like time had collapsed and Lenny was all ages at once, dying, but also back to an age when his parents drove us to the mall in their cutlass supreme.

Speaker 15 So if you want the front seat, go grab it now.

Speaker 1 The delusions were tender and vulnerable, and observing them was like standing over his bed, watching him dream.

Speaker 15 Maybe I should just go home.

Speaker 15 I'm dead tired.

Speaker 15 For some reason, we're at the Y taking a course.

Speaker 15 We're at the Y. We're at the YMHA taking a course.

Speaker 15 Fuck, I'm really delusional.

Speaker 1

No, it's okay. It's okay.

It's okay. I'll tell you if I can't follow.

Speaker 15 It's so weird, though, that I would have such a delusion. Maybe it's a subconscious desire to visit with you in a normal,

Speaker 15 in a normal setting.

Speaker 1 Yeah, yeah.

Speaker 15 We're visiting for holidays, normal, everything's normal.

Speaker 15 So, um,

Speaker 15 when was it when were we going to see each other

Speaker 1

in a couple weeks. The plan is for me to see Lenny during a visit back home.

My first since COVID.

Speaker 15 Hope I last that long. Yeah.

Speaker 15 No, I'm serious. I'm not being facetious.

Speaker 5 Yeah.

Speaker 1 Yeah.

Speaker 15 It's down to the wire.

Speaker 15 Maybe the last few weeks of things.

Speaker 15 Maybe, I don't know.

Speaker 15 Don't get depressed or anything, huh?

Speaker 1

Lenny wasn't just saying, I don't want to bum you out. He was one of the few people who knew how fragile I could be.

Even now, he was trying to protect me, even as he was dying.

Speaker 15 It's hard to say that, but I wish you were here.

Speaker 1 Yeah.

Speaker 1 Recently, my therapist recommended ketamine to me, a drug sometimes prescribed for untreatable depression.

Speaker 1 In my case, she thought it might help shift my perspective, which still tends towards darkness.

Speaker 1 A day after Lenny and I had this conversation, while taking several hits from my ketamine inhaler and about to go for a Saturday morning run, I was suddenly overcome with sobbing and a feeling of unreality.

Speaker 1 As a man inured to epiphanies, I was shaken.

Speaker 1 Like most, I don't often see my existence on Earth approximating anything close to a quote-unquote arc. Instead, things come in flashes.

Speaker 1 I'm four years old eating a chocolate bar at my Aunt Tilly's house, taking such tiny bites that Tilly calls me the mousy. My theory is that if the bites are small enough, it will last forever.

Speaker 1 I'm six, regretting having told my father about my kindergarten crush because he's just told a table full of relatives about it. I will never trust this man again, I think.

Speaker 1

I'm 15 and seeing a breast for the very first time. European sunbathers are at the same beach as me.

The image will claw its way into my thoughts over and over for the next 10 years.

Speaker 1 I'm 16, getting turned down to prom on a city bus. Lorraine Kaufman is telling me that only I would ask someone to prom on a city bus.

Speaker 1 Then, for some reason, I'm 50. and moving to Minnesota.

Speaker 1 While waiting at JFK for the flight that will take me and Emily and our then two-year-old son Aggie to our new life, Agi walks up to a stranger and hugs his legs and I burst into tears.

Speaker 1 A smell, a meal, a day at the beach, and so goes a life.

Speaker 1 Without the record button pressed down, life is fragmented and fast and nearly impossible to make sense of. Narrating it helps me to shed light, but always in retrospect.

Speaker 1 With the ketamine coursing through me, though, I saw the dots illuminate and connect, each handing off with purpose, one to the other like a succession of dominoes.

Speaker 1 Tracing the seemingly useless years that got me to where I was, with the wife, the child, the job, it all felt so precarious, like I was standing on a narrow column of shoeboxes.

Speaker 1 It filled me with vertigo.

Speaker 1 To the question of what one owes a childhood friend, in my case, I owed Lenny everything.

Speaker 1 It was through knowing him in those early years that the base of the tower was formed. It was in making tapes together in his bedroom that I discovered a feeling I'd pursue towards a career.

Speaker 1 Suddenly, I could see how everything counted, that Lenny counted, that my love for Lenny counted. I wanted Lenny to know this.

Speaker 1 I wanted him to know that while our personalities might have driven us apart, a deep-rooted love brought us back together.

Speaker 1 But later that day, I got a call from my mother, informing me that Lenny had died.

Speaker 5 In today's super competitive business environment, the edge goes to those who push harder, move faster, and level up every tool in their arsenal. T-Mobile knows all about that.

Speaker 5 They're now the best network, according to the experts at OOCLA Speed Test, and they're using that network to launch Super Mobile, the first and only business plan to combine intelligent performance, built-in security, and seamless satellite coverage.

Speaker 5 With Supermobile, your performance, security, and coverage are supercharged. With a network that adapts in real time, your business stays operating at peak capacity even in times of high demand.

Speaker 5 With built-in security on the first nationwide 5G advanced network, you keep private data private for you, your team, your clients.

Speaker 5 And with seamless coverage from the world's largest satellite-to-mobile constellation, your whole team can text and stay updated even when they're off the grid. That's your business, Supercharged.

Speaker 5

Learn more at supermobile.com. Seamless coverage with compatible devices in most outdoor areas in the U.S.

where you can see the sky.

Speaker 5 Best network based on analysis by UCLA of Speed Test Intelligence Data 1H 2025.

Speaker 6 There's more to San Francisco with the Chronicle. More to experience and to explore.

Speaker 6 Knowing San Francisco is our passion.

Speaker 6 Discover more at sfchronicle.com.

Speaker 12 At Blue Dot, we're designers. Before you see any new furniture from us, we've already seen it a hundred times.

Speaker 12 From that first sketch to our fifth prototype, we dig at every detail and scrutinize every sit until the final silhouette emerges into everything good design should be.

Speaker 12

Useful, timeless furniture enjoyed by everyone. Blue Dot.

Visit us at blue dot.com, B-L-U-D-O-T.com to enjoy 20% off at our annual sale.

Speaker 1 In the months after Lenny's death, I'm unable to let go of how I wasn't there for him in his last days. I obsess over what his final moments might have been like.

Speaker 1 I begin accidentally calling my son by Lenny's name. I do this so often that eventually, my son begins to ask, who in the world is Lenny? I try to answer him but never know quite how.

Speaker 1 We were best friends when I wasn't much older than you, I say.

Speaker 1 And then I get COVID and I isolate in my basement. I watch all the old movies Lenny and I used to watch, Animal House, Monty Python, Annie Hall, but instead of laughing after each punchline, I cry.

Speaker 1 Lenny had an older cousin named Betsy, who taken on the task of cleaning up Lenny's basement.

Speaker 1 I reached out to see if Betsy could set aside some of Lenny's art or photos for me, but she said that wasn't something I should pursue.

Speaker 1 It's not a situation where I don't think you'd want any of his coveted items.

Speaker 1

That place was a hoarder's paradise. It was filthy.

That place has not been cleaned in 40 years easily.

Speaker 1 And there was vermin. It probably could have been condemned.

Speaker 1 Betsy says that Lenny had taken the baseboards off the walls with an eye towards renovation, but then he let the project go and never put them back, which allowed mice into the house, and the mice got into everything.

Speaker 1 My dad had stopped by to do an errand for Lenny's mom and had the same kind of report.

Speaker 1 It was like going into a dark subterranean world, he said. My father described Lenny's room as cluttered with books and DVDs from floor to ceiling, the windows blocked out so the sun couldn't get in.

Speaker 1 How could anyone live under those circumstances, my father said.

Speaker 1 How could anyone? And especially how could Lenny? I keep thinking about how when we were kids, winding up in our parents' basements would have been our worst nightmare.

Speaker 1 How could Lenny have ended up living out his last days in the very place he despised most?

Speaker 17 That was always the thing that he never wanted to happen.

Speaker 1

This is Lenny's ex-girlfriend, Louise. Lenny and Louise dated in their 20s.

I first met her at a bar one night after having not seen Lenny in years.

Speaker 1 They were coming from a Kiss concert, and both Lenny and Louise's faces were painted. Louise as Peter Chris, and Lenny as Ace Freely.

Speaker 1 They both wanted to go as Ace, but Lenny said that would have been ridiculous.

Speaker 17 I think I was 18 years old when I met him.

Speaker 17 Oh, I remember he just,

Speaker 17 there was this

Speaker 17 depth

Speaker 17 about him that I recognized immediately. And it just automatically attracted me to him.

Speaker 17 I remember being on the back of his motorcycle and being scared shitless every time.

Speaker 17 Holding on to him so tight. I remember his dog, Max, and how much he loved that dog.

Speaker 1 Yeah.

Speaker 17 I mean, to know that he finished there in the basement.

Speaker 17 Why?

Speaker 1

Not only did Lenny hate the basement, he hated the whole suburb of Chaomity. We both did.

We attended Chaomity High, nicknamed Comedy High, because it was so bad it was laughable.

Speaker 1 Pipe bombs in the bathrooms, a geography teacher who was a flat earther, and a music teacher who married a student. I eventually left Chaomity, but Lenny never did, never even left his childhood home.

Speaker 1 How could our lives have diverged so?

Speaker 1

He was very unhappy. This is Dimitri, a high school acquaintance who Lenny reconnected with on Facebook in the last year of his life.

Dimitri was the person Lenny saw most during his illness.

Speaker 1 He works at a local Greek restaurant and would bring Lenny salads at the end of his shift. He was lonely.

Speaker 1 He used to talk about how it would have been nice if he had a girlfriend and some kids, or if he had a kid, it would have been nice.

Speaker 1 She was always alone.

Speaker 1 I never saw him with anybody, ever.

Speaker 1 He would like,

Speaker 1 he would ask me to hug him a lot.

Speaker 1 When he was sick, he would always ask me to hug him.

Speaker 1 I think Leonard didn't feel really much love in his life, man.

Speaker 1

Dimitri also knew that Lenny didn't want the basement for his home, let alone his final home. When I tell him how I've been trying to make sense of how it happened, he has a theory.

Drugs.

Speaker 1 Drugs. When you say drugs, you mean pot.

Speaker 1 Pot, mushrooms, LSD.

Speaker 1 Leonard used to like to take acid, a lot of acid, and just trip out in his room in the dark.

Speaker 1 I have a dog lookout for whatever works, bro. Whatever keeps the demons away there, but that's a little fucked up.

Speaker 1 Ending up in the basement solely because of drugs doesn't ring true to me. While the drugs might have helped with the demons, they didn't create the demons.

Speaker 1 Plenty of people smoke pot, take LSD, and still leave the house, travel the world.

Speaker 9 Lenny, I'll kill you!

Speaker 1 Among my childhood cassettes is another of my mother's performances, but this one wasn't a soap opera audition. It's of my mother pretending to be her best friend, Lenny's mom, Hannah.

Speaker 9 I'll kill you! I'll take the blade! I'll kill him!

Speaker 1 During those last conversations, Lenny confessed to not only feelings of resentment towards his own mother, but towards my mother too, for taking up so much of his mother's time, time she could have spent on him.

Speaker 1 As for his dad, Lenny saw Izzy as a constant threat. This is from another flip and wheel tape.

Speaker 9 Okay, the lines are open now.

Speaker 1 In the play, I perform the part of Lenny's father, who crashes straight into the flip and wheel show.

Speaker 3 Oh, shit. What is this?

Speaker 9 You stupid good, smack it up.

Speaker 1 You stupid. Ava, come on, you stupid ass.

Speaker 1 Izzy would get physical on occasion, but our parents weren't so different. My father favored the belt while Izzy delivered what he called pachkas or slaps.

Speaker 1 And in terms of our mothers, if Hannah had been so often absent because of her friendship with my mother, then it meant my mother was absent too. So was Lenny just more sensitive than I was?

Speaker 1 Or was he dealing with more than I knew?

Speaker 1 Okay,

Speaker 17 you just jogged in memory.

Speaker 1 This is Louise again, Lenny's ex-girlfriend, with another theory. Louise recalls a day in college when she stumbled upon what felt like a key, a key that predates the drugs, me and Lenny's friendship.

Speaker 1 It even predates the upbringing he received from his parents.

Speaker 17 It was my class for developmental biology.

Speaker 1 Okay.

Speaker 17 And we were studying the brains of children at that point between zero and 12 months.

Speaker 17 And we were looking at separation anxiety, and we were studying that.

Speaker 17 And I remember

Speaker 16 being appalled

Speaker 17 when I learned

Speaker 17 that at seven months, that is when

Speaker 17 a child's separation anxiety develops. That's when they know what their mother's face looks like, and that's when they start crying when you're handed to another person.

Speaker 17 And I remember being appalled because I remember Lenny telling me that he was adopted when he was like six months old

Speaker 17 and that his mom told him that all he ever did was cry.

Speaker 17 And I remember coming home that day after school and going, oh my God, no wonder you cried all the time because you knew that this wasn't your mom.

Speaker 1 To heal from the loss of his biological mother, to help him deal with just being a sensitive kid, Lenny could have used extra support. But instead, he got less.

Speaker 3 Just before his mother was kicked out of the convent, he was christened Andy Asphelt.

Speaker 1 Just as I had created the alter ego of Nedley to feed my id, Lenny created an alter ego named Andy that fed Lenny with something I could never put my finger on.

Speaker 1 But re-listening to the numerous Andy tapes we recorded all these years later, Andy feels like an expression of Lenny's vulnerability, his desperate need for more love from a parent.

Speaker 3

Through the years, he was raised with fellow orphans. He never knew the meaning of mother or father.

All he knew the meaning was of hate.

Speaker 3 All the kids would nickname

Speaker 3 him.

Speaker 3 You're a bastard.

Speaker 3 Andy was the only four-year-old child in the um orphanage who every day would sit down in his bed and contemplate suicide.

Speaker 3 Oh, no one loves me.

Speaker 9

Everyone hates me. What did I do? I've got to leave.

I've got to get out of here.

Speaker 9 I got to get out of here somehow. Well?

Speaker 2

I knew by age six I was in trouble. I knew by age 12 that life's going to to be a little harder than I thought.

And I knew by the time I was 18, 19 that I got to get out of here and then stay out.

Speaker 2 I just, you know, I'd already learned helplessness, I guess.

Speaker 1 I've always wanted to write a book, Lenny said during one of our late-night conversations, where everything the hero does is wrong. I think a lot of books are like that, I said.

Speaker 1 A lot of lives are like that.

Speaker 1 You don't understand, Lenny said. And maybe I didn't.

Speaker 1 Perhaps a lot of what we take as a life choice is already encoded in us at a very young age, younger than we can even remember. And by then, it's already too late.

Speaker 1 The moments are already handing off, one to the other, like those dominoes that cannot be stopped.

Speaker 1 Supposedly, Lenny's biological mother was a 15-year-old girl who eventually came to realize she couldn't raise him on her own.

Speaker 1 Who knows what those first six months were like for Lenny and how they dictated the life to come? Maybe Lenny was wrong.

Speaker 1 Maybe his paralysis, his inability to leave the nest, wasn't, as he said, learned helplessness, but innate helplessness, the kind a baby feels. Maybe for Lenny, the feeling just never faded away.

Speaker 1

I was with him all the way to the end. This is Dimitri again.

I remember the last day there.

Speaker 1 She goes to me, he calls me up, he goes, look, he goes, can you come over and be with me tonight? tonight he goes because i'm gonna die he said it

Speaker 14 i was like shut up i'm half i go you're gonna die he goes no he goes i'm gonna die he goes i'm gonna die tonight he goes can you just come be with me he goes i don't want to be alone you know i'm like yeah yeah of course

Speaker 14 then i stayed with him and um

Speaker 14 we smoked a couple of joints together

Speaker 14 um

Speaker 14 Had a couple of drinks, a couple shots of whiskey, I did.

Speaker 14 And I was just telling him, you know, Leonard, I go, it's okay. You know,

Speaker 14 you can go if you want, you know, don't worry about it. You know, just if you need to go, just go.

Speaker 1 Because I never made it to Shamity before Lenny died, because I wasn't there to hug him or to just hold his hand, I'm left with a terrible sense of loss.

Speaker 1 Of the many questions I have about Lenny's last days, the one that weighs on me most heavily is about Lenny's anger. and whether it ever subsided.

Speaker 1 Do you remember what his state of mind was

Speaker 1 on that last day when you went there? Did he?

Speaker 1 Oh, yeah, yeah, he was completely at peace. He wasn't worried or scared at all.

Speaker 1 I think he had accepted his fate.

Speaker 1 I think he was just, honestly, I think he was just tired.

Speaker 8

I think he wanted to just go. He seemed really okay, though.

He wasn't nervous. He was just quiet.

Speaker 1

I have a video of his last words. Oh, wow.

I'll go. What message do you want to share with everybody, bro? Now that you're at the end,

Speaker 1 dimitri sends me the video he took and when i hit play i gasp i knew how sick lenny had been but i guess irrationally i'd been imagining him on the other end of the phone line looking more like the last time i'd seen him at the restaurant with his parents in the video though lenny looks cadaverous

Speaker 1 and he sat for about ten seconds he thought a bit and he goes

Speaker 8 love more fight less

Speaker 12 Fighting doesn't get you far.

Speaker 1

Love more, fight less. Fighting doesn't get you far.

Nor does anger.

Speaker 1 In one of our last phone calls in the final days of his life, Lenny said that he was so weak he could hardly lift himself from the toilet without his mother's aid.

Speaker 1 I asked if, in general, his mother was being helpful.

Speaker 15 She's trying. She really is trying.

Speaker 1 Oh.

Speaker 15 I have to hear, and she's succeeding, too.

Speaker 15 She's the only help I got. I need her.

Speaker 1 It was the first I'd ever heard Lenny acknowledge his mother's effort. Which is to say, it's the closest I'd ever heard Lenny come to forgiving her.

Speaker 1 I knew Lenny in the beginning and can only speculate about the middle, but I do see that in the end, in spite of the pain and the delusions, he allowed his sweetness to shine through.

Speaker 1 While I may never know where Lenny's anger came from, I do know where it went.

Speaker 1 He laid it down at long last

Speaker 1 to rest.

Speaker 1 Now that the furniture's returning to its goodwill home

Speaker 1 now that the last month's rent is scheming with the damaged deposit, take this moment to decide

Speaker 1 if we meant it, if we tried,

Speaker 1 but felt around for far too much

Speaker 1 from things that accidentally touched.

Speaker 1 This episode of Heavyweight was produced by me, Jonathan Goldstein, and supervising producer Stevie Lane, along with Phoebe Flanagan. Our senior producer is Kalila Holt.

Speaker 1

Production assistants by Mohini Medgauker. Special thanks to Lauren Silverman and Neil Drumming.

Editorial guidance from Emily Condon.

Speaker 1 Bobby Lord mixed the episode with original music by Christine Fellows, John K. Sampson, Blue Dot Sessions, Katie Condon, and Bobby Lord.

Speaker 1

Additional music credits can be found on our website, gimletmedia.com/slash heavyweight. Our theme song is by The Weaker Thans, courtesy of Epitaph Records.

Heavyweight is a Spotify original podcast.

Speaker 1 Follow us on Twitter at heavyweight, on Instagram at heavyweight podcast, or email us at heavyweight at gimletmedia.com.

Speaker 1 You can also follow our show on Spotify and tap the bell to receive notifications when new episodes drop. We'll be back next week with a new episode.

Speaker 7 This is Justin Richmond, host of Broken Record. Starbucks pumpkin spice latte arrives at the end of every summer like a pick-me-up to save us from the dreary return from our summer breaks.

Speaker 7 It reminds us that we're actually entering the best time of year, fall. Fall is when music sounds the best.

Speaker 7 Whether listening on a walk with headphones or in a car during your commute, something about the fall foliage makes music hit just a little closer to the bone.

Speaker 7 And with the pumpkin spice latte now available at Starbucks, made with real pumpkin, you can elevate your listening and your taste all at the same time. The Starbucks pumpkin spice latte.

Speaker 7 Get it while it's hot or iced.

Speaker 18 Witness the new season of Reasonable Doubt streaming on Hulu September 18th. LA's most successful attorney, Jack Stewart, defends a young actor accused of murder.

Speaker 18 Follow Emayati Coronaldi, Morris Chestnut, Joseph Sokora, and guest stars Cash Dahl and Laurie Harvey as they face off in the year's most sensational trial.

Speaker 18

In the pursuit of justice, every move counts. Reasonable Doubt Season 3 is streaming on Hulu and Hulu on Disney Plus September 18th.

Hulu on Disney Plus for bundle subscribers. Terms apply.

Speaker 4

You've probably heard me say this. Connection is one of the biggest keys to happiness.

And one of my favorite ways to build that? Scruffy hospitality.

Speaker 4

Inviting people over even when things aren't perfect. Because just being together, laughing, chatting, cooking, makes you feel good.

That's why I love Bosch.

Speaker 4 Bosch fridges with VitaFresh technology keep ingredients fresher longer, so you're always ready to whip up a meal and share a special moment.

Speaker 4

Fresh foods show you care, and it shows the people you love that they matter. Learn more, visit BoschHomeus.com.

This is an iHeart podcast.