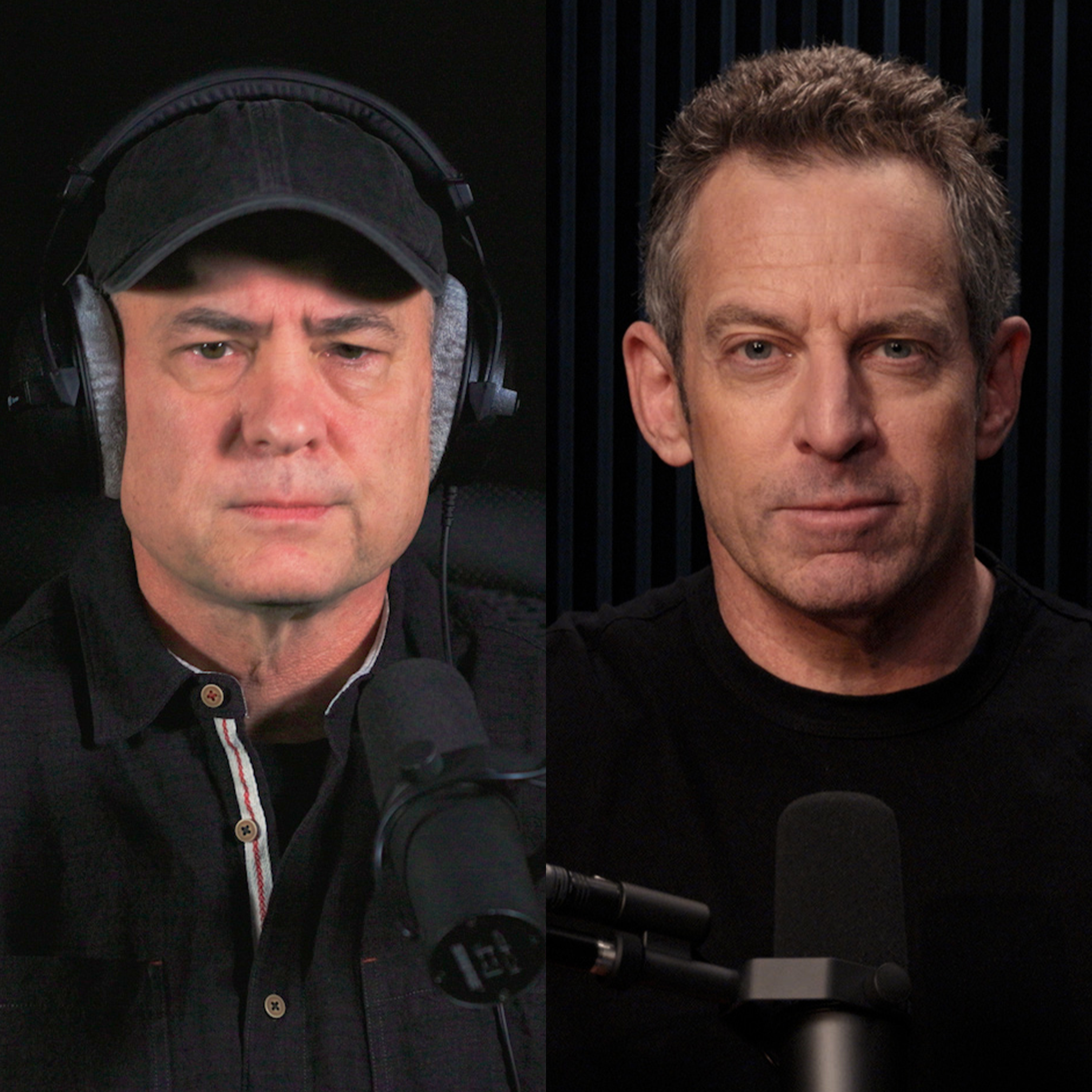

#433 — How Did We Get Here?

Sam Harris speaks with Dan Carlin about the decades-long buildup to our current political moment. They discuss the growing powers of the presidency, executive orders, different factions within the Republican Party, the fragmentation of our society, Libertarianism, the growing prospect of political violence, racism and scapegoating, foreign interference in American politics, immigration, global trends towards autocracy, whether “gatekeepers” in the media are necessary, holocaust denialism, and other topics.

If the Making Sense podcast logo in your player is BLACK, you can SUBSCRIBE to gain access to all full-length episodes at samharris.org/subscribe.

Press play and read along

Transcript

Transcript is processing—check back soon.

Making Sense with Sam Harris — #433 — How Did We Get Here?