The BLS has a $700 million budget. What's its ROI?

Budget cuts may be in the Bureau of Labor Statistics' future. But the data collected by the BLS is critical for federal decision making. In this episode, we calculate if the $700 million investment is worthwhile. Plus: Firms that spend the most on AI slash tons of jobs, economic uncertainty drives up the price of gold, and mortgage rates fall — which is good for buyers but a bad sign for the overall economy.

Every story has an economic angle. Want some in your inbox? Subscribe to our daily or weekly newsletter.

Marketplace is more than a radio show. Check out our original reporting and financial literacy content at marketplace.org — and consider making an investment in our future.

Press play and read along

Transcript

Since 2011, American Giant has been making everyday clothing with extraordinary effort, not in far-off factories, but right here in the USA.

We obsess over fabrics, fit, and details, because if you're going to wear it every day, it should feel great and last for years.

From the cut of a hoodie to the finishing of a seam, nothing is overlooked. Our supply chain is tight-knit and local, which means less crisscrossing the country and more care in every step.

The result is durable clothing, t-shirts, hoodies, sweatpants, and denim that become part of your life season after season.

This isn't fast fashion, it's clothing made with purpose by people who care as much about how it's made as how it fits. Get 20% off your first order with code STAPLE20 at American-Giant.com.

That's 20% off your first order at American-Giant.com with code STAPEL20.

This podcast is supported by Odo. Some say Odo business management software is like fertilizer for businesses because the simple, efficient software promotes growth.

Others say Odoo is like a magic beanstalk because it scales with you and is magically affordable.

And some describe Odoo's programs for manufacturing, accounting, and more as building blocks for creating a custom software suite. So Odo is fertilizer, magic beanstock building blocks for business.

Odoo, exactly what businesses need. Sign up at odo.com.

That's odoo.com.

Yes, it's a lot of jobs not added. Yes, it is not great.

But also, yes, it's important to understand exactly what is going on. From American Public Media, this is Marketplace.

In Los Angeles, I'm Kyle Risdoff. Tuesday 9, September.

Good as always to have you along, everybody. We begin today with the number 911,000.

As you have surely heard by now, that's how many fewer jobs the economy added from April of last year to March of this year than we had thought.

As I said, not great, but as I also said, or more accurately perhaps implied, it is complicated. Catherine Ann Edwards is a labor economist.

She's also the host of the Optimist Economy Podcast.

Welcome back to the program.

Thank you so much for having me. So this is a big number.

Let's do the gut check first. What was your first thought?

It was actually about in line with what I thought it would say. Really?

Yes, it's a big number, but we've known for a while that our labor market is slowing.

We've essentially had a weak and weakening labor market for the past two and a half years.

This twice over weakness has first come in trying to beat back inflation, and then the labor market itself is being beaten back by tariffs.

The number of jobs posted has been slightly rosy, and so this is really bringing this in line with expectations. All right.

So do me a favor and

acknowledgement that this is a laypersons podcast. The nuts and bolts of how this revision happened, please.

I think the easiest way to understand it is to start at the end.

What is the most accurate version that we can get of the number of jobs in the U.S. economy? Well, that's easy.

We have payroll tax records.

These people by law have to tell the federal government or their state government how many jobs they have because they pay taxes on them. So that is the answer.

We just need to count the number of jobs that employers are paying taxes for. The problem is that that can take six months to a year.

And so the question for agencies like the BLS is how to extract information out of what we know to be the most accurate data in a more timely fashion.

The very first version of it comes from the initial release just days after the month ends. That comes from the current establishment survey.

And in between that first number and this last number is simply working our way back to the answer that we know is there.

Can we talk, though, about the monthly numbers for a second as well

as a way to sort of, as you said, begin at the end? There are known secular issues

with the monthly jobs numbers that we get, right? There's lack of resources, there are survey responses, all of those things, which contribute to

the delta here, right? The difference?

Yes. And then

there's the survey itself, which is a sample of the universe or the census of all payroll tax paying employers in the U.S.

So there's kind of one batch of problems is with the actual survey and its collection. And then the second batch of problems is with the survey and sampling design and if it's matching the census.

So what we get from the monthly revisions is really problems with the survey collection. What we get from the annual benchmark revisions is where the survey design itself is drifting from the census.

So, it's testimony to both the integrity and the commitment of the Bureau of Labor Statistics that we get to have all of this information on hand because we learned something not just about the number itself, but about the economy through each revision.

Up and down, that tells us something. Yeah, I want to get to the integrity of the BLS here in a second, second, but I do want to do

a contrarian point of view here. There are 160, 165 million people in this economy who are employed.

In that context, 911,000 jobs just doesn't seem like that much.

No, it's not. And even in terms of revisions, it would be the largest one since 2009 if it holds, because of course, they'll revise this number again, too.

Right. But

the size itself is less worrying than the direction and the trend. So the link between the monthly survey and the census that we get has to have some assumptions that go with it.

And so, how's this for the laid person podcast? This is really about the economy drifting away from the predictions of the birth-death model.

Oh, my.

In regular human terms. Birth death of firms, right? We should be clear about that.

Birth-death of firms.

So in human language, the BLS, when it sends out the survey of employers to get an estimate of the monthly number of jobs that we're producing, has to make some assumptions about how quickly firms are entering and leaving basically business.

And when there's a big revision, that means most of the time it means that the birth-death model assumptions are off, which means either it goes in both directions.

Either it means there's a bunch of firms joining that are above the pace predicted by the model, or there's firms leaving that are slower than the pace predicted by the models, which again makes these revisions their own kind of indicator.

A big downward revision means that we thought there were more businesses joining the economy than there were. Right.

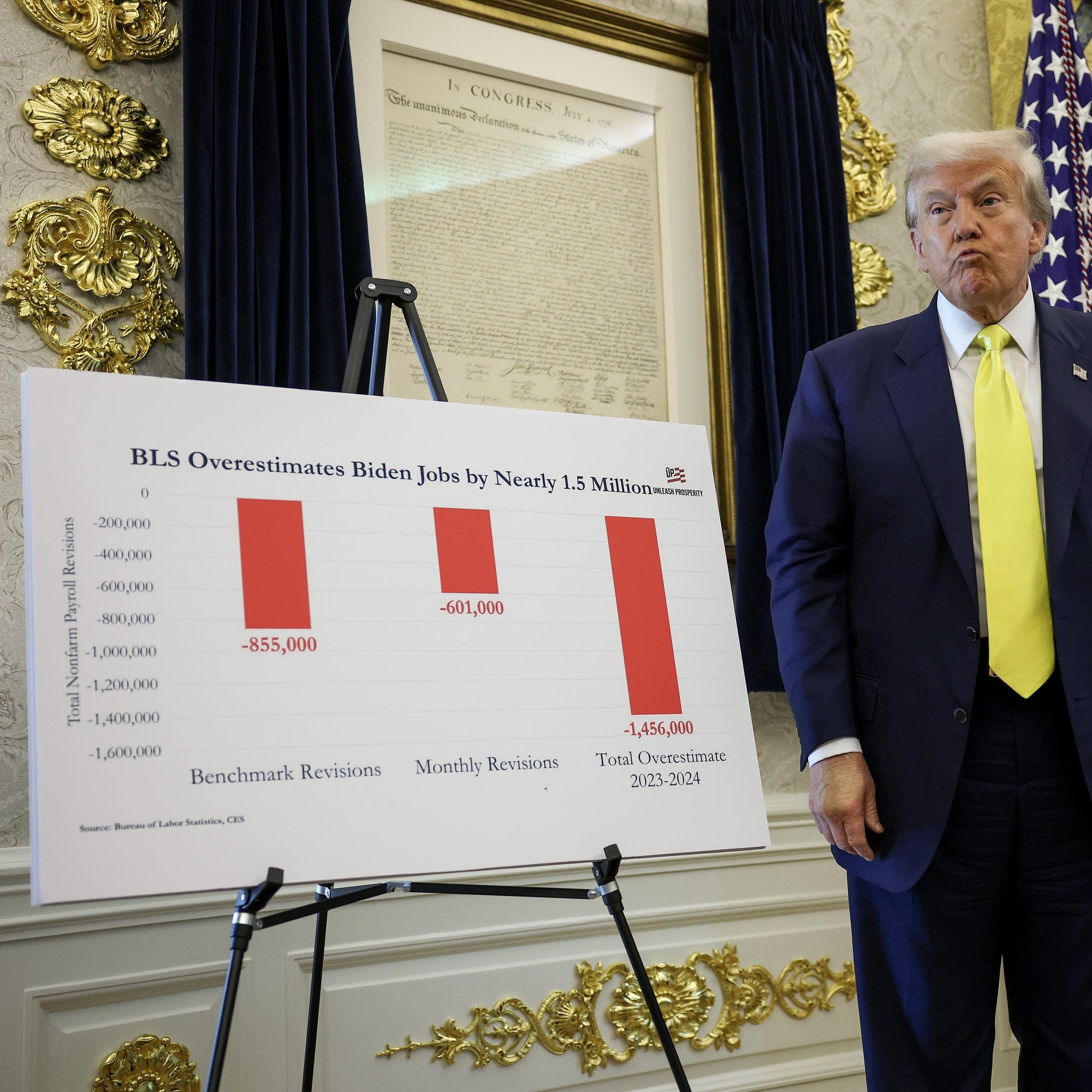

About the quality of this data, the Trump administration and his advisors and cabinet officials are doing their darndest to politicize the Bureau of Labor Statistics.

Is there anything in this revision that makes you question the accuracy and the integrity of any of these numbers?

Absolutely not.

Katherine Ann Edwards, labor economist, also the host of a podcast called The Optimist Economy. Thank you for your time.

Really appreciate it. Thank you for having me.

Wall Street on this Tuesday.

Tell you what, revision schmavision. Traders just didn't care.

Details, numbers, when we get there.

Shares of Oracle were up 1.25% during the session today, another 27%

after hours and after the company's quarterly earnings report. Oracle is making banks snapping up Nvidia's AI chips and then renting out cloud computing power that uses them.

Company shares up 66.0%

in the past year.

However,

all of that said, Oracle has been cutting jobs, hundreds in the United States over just the past month. So too have other leaders in the AI boom.

Microsoft and Google and Meta have all laid off thousands this year.

The irony, of course, is that while AI productivity gains, that's in air quotes, are sometimes cited for reasons why companies don't need as many humans, the enormous piles of cash they are sinking into AI are limiting factors too.

Marketplaces Megan McCarty Carino has that one. The companies riding the highest on the AI wave are also making some of the deepest cuts.

And no, it's not just because of AI coding, says analyst Eric Suffert at Mobile Dev Memo.

I think what you're seeing with these layoffs is really more of a strategic realignment based on resource constraints. He says even the richest companies in the world have to prioritize.

The more attractive the opportunity, the sort of like more aggressively you want to pursue it. Even if it means sacrificing other parts of the business.

Oracle has scaled back its health division.

Microsoft cut gaming, and Meta trimmed the metaverse.

It's normal for a business to pivot to new opportunities, but the cost to play the AI game is on a whole new level, says Daniel Newman at Futuram Group.

There's physical data centers, there's real estate, there's energy. Immediately before the AI frenzy, Google and Microsoft spent 20 to 30 billion a year on infrastructure.

Now, it's two to three times that. Then there's the war for AI talent.

So instead of hiring, you know, a thousand workers at $100,000 a year, now you have one employee taking $100,000, $200 million.

Demand for AI is strong, but there's no guarantee this gamble will pay off, says Sarah Myers-West at the AI Now Institute.

There's just so much spend on this one really big bet, and they're shortchanging other areas, including

their own human resourcing. Still, companies keep upping the ante.

Last week, Meta said it's planning to spend about $600 billion on AI infrastructure in the next few years.

I'm Megan McCarty-Carino for Marketplace.

Here's today's, you know, market forces move in mysterious ways, man. Story.

Gold hit an all-time high today, above $3,700 for a single ounce of the shiny yellow metal.

It's up 38% year to date as both individual investors and big banks pile in. Marketplaces at Rebenishwar explains what is going on there.

Gold's current kick was actually born out of war.

This is the beginning of a Russian Russian invasion of Ukraine. The U.S.

would then freeze some of Russia's central bank assets. Chantel Skeven is head of research at Capital White Research.

Really, the sanctions that the Western world put on Russia was the start to an underlying change in

how gold is thought of as a safe haven, a store of value. When central banks around the world saw what happened to Russia, they started taking out a little insurance policy called gold.

Because you can freeze or seize money in international bank accounts, it is a lot harder to seize gold bars from a vault. But that's not the only reason gold is in such demand.

Global uncertainty is the major driver. Konstantinos Chrysikos is with online brokerage Kudo Trade.

Central banks and investors both have looked at the U.S. and backed away slowly.

Concerns about slowing economic growth, geopolitical tensions, and of course fears of prolonged inflation have all pushed investors actually towards safe haven assets like gold. Safe haven assets.

You probably won't lose money in them, but you might not make much either. The thing with gold, it's a real asset that doesn't pay any interest.

Hamad Hussein is an economist at capital economics.

Bonds, for example, do pay interest, but those interest rates are falling.

So when interest rates fall, then that increases the relative attractiveness of gold compared to bonds. So, investors say, Yeah, I'm not missing out on too much if I park my money in gold.

And the way things have gone this year, they did just fine. In New York, I'm Sabri Benishore for Marketplace.

Gold's been going up. The price of borrowing to buy a house has been going down.

The average 30-year fixed-rate mortgage fell to 6.5% last week. That's according to Freddie Mac.

Mortgage Daily News reports that this week it's averaging just 6.3%.

Regular listeners might know mortgage rates tend to follow the yield on the 10-year Treasury note, which, again,

regular listeners, those yields have been sliding. Marketplace's Mitchell Hartman is on housing for us today.

Home sales typically surge in the spring and summer. Not this year, though.

Portland, Oregon real estate broker Israel Hill has seen list prices, especially on the most expensive homes, get cut again and again to attract buyers.

Out of the 70 deals he's done recently, I think 58 of them or 60 of them were all sold for well under where they started.

Nationwide, home prices have flattened out, just as mortgage rates are falling.

Lawrence Yoon at the National Association of Realtors expects the 30-year fixed rate to hit 6% by the end of the year and make life easier for some would-be buyers.

Anytime mortgage rate moves lower, even a small amount, we do see additional people who qualify to purchase a home and the situation is likely to get even more favorable for homebuyers as the fed moves to juice a flagging economy says susan wachter at the wharton school the likelihood is that the economy will slow down further and that rates will fall further

but that flagging economy also has negative consequences which portland broker israel hill is already seeing more affordable homes hitting the market as local employers lay off thousands of workers hand in hand with lower mortgage rates, that's good for would-be buyers, but he doesn't exactly want to celebrate.

We try to be gentle about going on and getting all super excited about the interest rates going down because it's like, yeah, we're going to the recession, rates are coming down, buy a house.

Still, he says, for folks who do have steady jobs, lower rates could help unlock the dream of home ownership. I'm Mitchell Hartman for Marketplace.

Coming up. She's 78 years old, and every morning she starts her day with a bowl of cereal.

There is data in everything, gang, even in a bowl of rice krispies. First, though, let's do the numbers.

Dow Industrial is up 196 points today, a bit more than 4 tenths percent,

711 the nasdaq added 80 points just shy of four tenths percent twenty one thirty hundred and seventy nine the s p 500 up 17 points just over a quarter percent 65 and 12

17.4 billion dollars that's how much microsoft is going to pay cloud infrastructure provider nebius group to provide ai capacity at a data center in new jersey nebius accumulated 49 and 4 tenths percent today microsoft basically unchanged to see also though megan mccarti Shirino's story on AI just a minute or two ago.

Bonds down, yield on the tenure, T-note up 4.08%.

You're listening to Marketplace.

The year-in-clarance sale is going on now at your local Honda dealer. Honda cars, SUVs, and trucks are on clearance during happy Honda Days.

Get 2025 accords, pilots, and ridge lines on clearance with big savings on the full Honda line. Gas, hybrids, and EVs.

All new Hondas are in stock. Honda, KBB.com's best value and performance brand.

This is the time to get a new Honda with clearance savings. Search your local Honda dealer today.

Base Out 2025 Consumer Choice Awards from Kelly Blue Book. Visit KBB.com for more information.

A 150-foot-tall Branosaurus? That's something you have to see to believe.

Make sure to fill up with Chevron with Techron along the way, giving cars unbeatable mileage and helping to keep critical engine parts clean so you can fuel up on memories.

Chevron with Techron, fueled by possibility.

When you fill up with 76, you're ready to go to that music festival you see posted about each year but have never been to.

And you're ready to go?

Do a sunrise yoga class before work.

And go

dog sitting and try to get get the zoomies under control. Know who wants to go?

Go here, go there, go anywhere with 76.

With Venmo Stash, a taco in one hand, and ordering a ride in the other means you're stacking cash back. Nice.

Get up to 5% cash back with Venmo Stash on your favorite brands when you pay with your Venmo debit card.

From takeout to ride shares, entertainment and more, pick a bundle with your go-to's and start earning cash back back at those brands. Earn more cash when you do more with Stash.

Vimmo Stash Terms and Exclusions apply. Max $100 cash back per month.

C terms at venmo.me slash stash terms.

This is Marketplace. I'm Kai Rizdahl.

Catherine Ann Edwards and I were talking about the big BLS revision up at the top of the program, both the why of it and what it's going to mean for how we're thinking about this economy.

But there is a lesson in there as well for the field of economics as a whole, in particular for the people teaching the the next generation of economists.

Abdullah Al-Birani teaches economics at Northern Kentucky University. We got him on the phone back at the start of the school year.

I read a column this morning, a newsletter actually, because that's what people do now,

by a law professor who was talking about the difficulty of teaching the law right now, his pedagogical obligations, at a time when law is being challenged, shall we say, in the current political environment.

And I wonder how you think, as a teacher, how you think about your obligation to your students with this data and

how they should think about it?

This has become a bigger conversation that we have. So errors, biases, and data with response rates being so much lower become a bigger concern.

So our teachings have evolved to make sure that we're

early, even in undergraduate levels, talking about measurement measurement error and confidence intervals in more detail than we probably did in the past.

Does this add, do you think,

to the economic friction that's happening right now?

I think trust is

a concern. And

economics requires you to have trust, either trust in the information, trust in the people talking about the economics and definitely in the policymakers.

If we don't trust the data, then we can't use it.

And if we don't use the data, then how's that going to impact our ability to decide in an economy and especially a capitalist economy that relies on information for us to make the best decisions for ourselves?

Are you worried?

I am concerned. I am concerned because

I'm a big believer in the capitalism that we have and the individual's right to make the decisions that are best for them.

And once you don't have data and information, your decisions are no longer probably optimal for you so regret becomes a big part of economic decision making because we're operating under incomplete information

so put yourself back in the classroom for me

as you stand in front of you know the class of 150 people or whatever it is in in econ 101 what's your uh What's your elevator pitch?

What's your, you know, here's why this matters to you, pitch.

yeah you're you're speaking my language now kai economic literacy is something that i'm extremely passionate about uh i believe every person uh in the world needs to know how the economy works and know how to navigate it and for my students what i really want them to to know is if they want to improve their overall well-being a good basic understanding of economics and the economic movements will help them navigate the complexity.

So if we're focused on improving the overall well-being of our society, economic literacy is a necessity. Aaron Powell,

I was perusing your CV before we came in and sat down, and I note that

in addition to your PhD, you've got a master's in economic theory.

What does economic theory tell you about this moment, about the changes that are happening in the American workplace, because of the pandemic, about global trade, because of the President's tariffs, because of the politicization of large parts of our economic system?

What I am seeing happen is we're starting to see more friction, and economists like to call it stickiness. And

the more friction you have in the economy, the more stickiness, the less likely that people will be able to respond to shocks and changes in the economy.

So we should probably expect more volatile business cycles in the near future because people are not utilizing information or don't have access to it. And

this creates

even more focus on how do we respond to shocks from a political standpoint, but from an economic standpoint as well.

Abdullah Al-Marani in Northern Kentucky. Professor, thanks for your time, sir.

I do appreciate it. My pleasure, Kanye.

Thank you.

You should know, just to add a little context to my conversation with Professor Alberani and with Catherine Ann Edwards, too, for that matter, that the White House wants to cut the budget for the Bureau of Labor Statistics for next year by about 8%

or so.

The BLS does produce the monthly jobs report, of course, but also the Consumer Price Index, a new version of which we are going to get on Thursday. But measuring prices for everything in this economy

don't come cheap, if you'll pardon the pun. Marketplace of Maria Hollandhorst has more now on the return on investment, the ROI, on the CPI.

What exactly goes into measuring inflation? Oh, how much time do we have?

Four minutes, maybe. Omer Sharif is president and founder of Inflation Insights, a research and analytics firm.

And he says to produce the CPI, the government first does an annual survey to figure out what consumers actually buy.

Once consumers are selected and agree to participate, they're essentially tracking their own spending. And so they're visited every three months over the course of a year by an analyst.

Who will ask what they bought recently. Like, I personally bought a used fridge and a new rug last month.

It was on sale.

And then separately, we're also doing what's called the diary survey, where they're asked to keep track on their own of different purchases that they make.

Just how much did you pay for that latte this morning? How much was your electricity bill? That information helps the BLS figure out how to weight items in the CPI.

And then to produce that monthly number on price changes, the good old-fashioned send somebody into the shop with a scanner and scan the price of the item.

The BLS collects around 100,000 prices across the country with just 2,000-ish full-time employees. Which is actually not a lot of people, quite frankly.

Especially when you consider that those employees also produce the jobs report, the producer price index, and other indicators as well. So that's the investment side of the equation.

But what are we getting from all that effort? Well, only three minutes left here, but private companies and researchers use the CPI all the time to understand how prices are moving.

And the government itself uses it too. It is the basis for the annual cost of living adjustment, or COLA, for both Social Security and the Supplemental Security income.

Kathleen Romig is Director of Social Security and Disability Policy at the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities.

That annual cost of living adjustment gets announced in October and goes into effect in January for most recipients. In 2025, it was 2.5%.

Let's talk about my mom, for example, who she's a Social Security beneficiary. She's 78 years old, and every morning she starts her day with a bowl of cereal.

Specifically?

My mom is a Rice Krispies girl. And like a lot of retirees, she pays for those Krispies.

Primarily through her Social Security benefit.

And that benefit increases every year along with the growth in prices, or also known as inflation. Inflation, as measured by the CPI.

If it's too low, seniors won't be able to keep up with rising costs. And if it's too high, the government could potentially overpay from the Social Security Trust Fund.

It's really in everyone's interest that we get it just right.

So I was kind of doing a little back-of-the-envelope calculation. Deborah Lucas is a professor of finance at MIT's Sloan School of Management.

Last year, the Social Security Administration paid about a trillion and a half dollars in benefits, which means that just one small data error in the CPI one that increased payments by a tenth of 1% or 10 basis points would cost taxpayers $1.5 billion annually.

And that's just one of the many ways the U.S. government uses the CPI.

The Treasury Department sells inflation index treasury bonds. Some government contracts have CPI adjustments built in.

And the IRS uses the CPI to adjust income tax brackets.

And the value just there covers the cost of the data collection and processing by many, many multiples. One wrinkle here is that the BLS's job is getting harder.

As Kai and Abdullah Al-Birani were just talking about, survey response rates have declined over the past decade, which makes collecting data more time-consuming and expensive.

At the same time, they've had big staff cuts, and that means they don't have enough people anymore to go to all of those stores in person that they used to go to.

Kathleen Roaming again at the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities.

And that means instead of getting real actual data about the prices of goods and services, BLS is forced to rely more on estimates.

The share of different sell-imputed figures in the CPI, which is basically a fancy way of saying educated guess, has increased to around 30% for the past few months. This time last year, it was 10%.

That means the BLS is doing fewer price checks on the actual cost of those rice krispies. I'm Maria Hollenhorst for Marketplace.

This final note on the way out today, brought to you by the Supreme Court of the United States and the International Emergency Economic Powers Act of 1977, sometimes referred to as AIPA.

The court announced this afternoon, kind of as expected, truth be told, that it is going to hear on an expedited basis the administration's appeal of a Court of Appeals ruling a couple of weeks ago that said the president's reciprocal tariffs, air quotes again, are illegal.

Arguments will be the first week in November. Jordan Manji, Zonio Maharaj, Janet Wynn, Olga Oxman, Virginia K.

Smith, and Tony Wagner are the digital team. And I'm Kyle Riznow.

We will see you tomorrow, everybody.

This is APM.

The year-end clearance sale is going on now at your local Honda dealer. Honda cars, SUVs, and trucks are on clearance during happy Honda Days.

Get 2025 accords, pilots, and ridge lines on clearance with big savings on the full Honda line. Gas, hybrids, and EVs.

All new Hondas are in stock. Honda, kbb.com's best value and performance brand.

This is the time to get a new Honda with clearance savings. Search your local Honda dealer today.

Face out 2025 Consumer Choice Awards from Kelly Bluebook, visitkvb.com for more information.