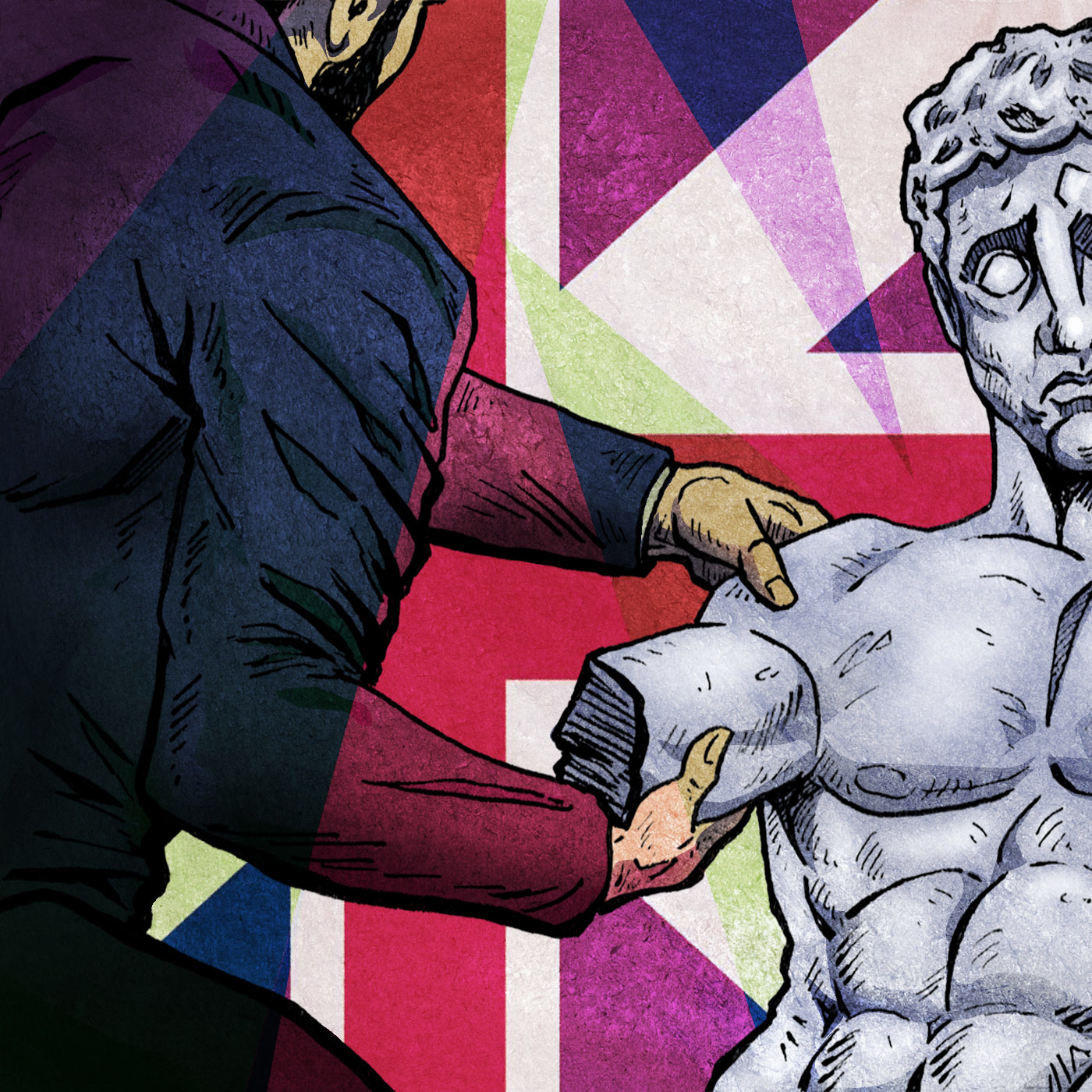

Episode #234 - Was The Parthenon Robbed? (Part I)

The Parthenon Sculptures, also known as the Elgin Marbles, are some of the most controversial museum objects in the world. In the early 19th century the Scottish aristocrat Thomas Bruce, the seventh Earl of Elgin, used his position as Ambassador Extraordinary to the Ottoman Empire to gain access to Athens' historic acropolis and remove priceless works of ancient art from the Parthenon. Since that time both the legality and the morality of the acquisition has been the source of controversy. Unfortunately, the debate around the Parthenon sculptures has been clouded by many historical myths and misconceptions. Should the marbles remain in the British Museum, or should they be returned to Athens? Tune-in and find out how a gift of ammunition, an "Old Turk", and lies to Parliament all play a role in the story.

Join Sebastian in Greece in 2026! Click HERE for a full itinerary and booking.

See Privacy Policy at https://art19.com/privacy and California Privacy Notice at https://art19.com/privacy#do-not-sell-my-info.

Press play and read along

Transcript

Transcript is processing—check back soon.