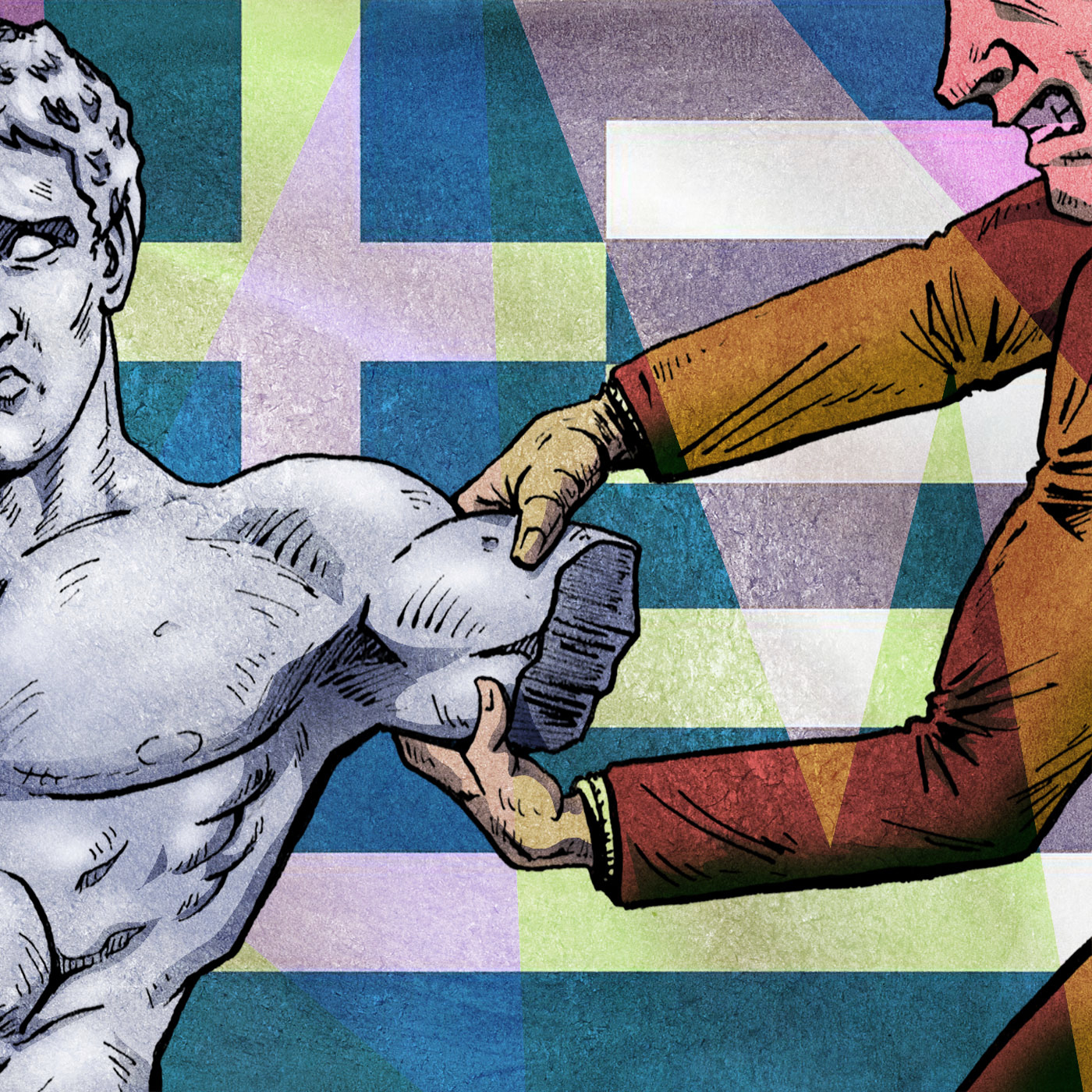

Episode #235 - Was The Parthenon Robbed? (Part II)

The Parthenon Sculptures have been hugely controversial objects from the moment that they arrived in England. The British public has long been split over the morality of keeping these famous works of art in London. In the early 1800's the famous poet Lord Byron went so far as to write angry poems castigating Lord Elgin for defiling Athena's temple. Over the last 200 years the topic of the sculptures has remained a perennial topic of public debate. Where are we at with that debate in 2025? Tune-in and find out how 19th century diss tracks, half a nose, and the "universal museum" all play a role in the story.

Come with me to Greece in September 2025! Check out the full itinerary HERE

Rula patients typically pay $15 per session when using insurance. Connect with quality therapists and mental health experts who specialize in you at https://www.rula.com/fakehistory #rulapod

See Privacy Policy at https://art19.com/privacy and California Privacy Notice at https://art19.com/privacy#do-not-sell-my-info.

Press play and read along

Transcript

Transcript is processing—check back soon.