A New Kind of Family Separation

– – –

Read more from Nick Miroff.

Read Stephanie McCrummen’s story: The Message Is ‘We Can Take Your Children’

– – –

Get more from your favorite Atlantic voices when you subscribe. You’ll enjoy unlimited access to Pulitzer-winning journalism, from clear-eyed analysis and insight on breaking news to fascinating explorations of our world. Subscribe today at TheAtlantic.com/listener.

Learn more about your ad choices. Visit megaphone.fm/adchoices

Press play and read along

Transcript

Speaker 1 You're cut from a different cloth.

Speaker 1 And with Bank of America Private Bank, you have an entire team tailored to your needs with wealth and business strategies built for the biggest ambitions, like yours.

Speaker 1 Whatever your passion, unlock more powerful possibilities at privatebank.bankofamerica.com. What would you like the power to do? Bank of America, official bank of the FIFA World Cup 2026.

Speaker 1 Bank of America Private Bank is a division of Bank of America NA member FDIC and a wholly owned subsidiary of Bank of America Corporation.

Speaker 2 This episode is brought to you by Progressive Insurance. Fiscally responsible, financial geniuses, monetary magicians.

Speaker 2 These are things people say about drivers who switch their car insurance to Progressive and save hundreds. Visit progressive.com to see if you could save.

Speaker 2 Progressive Casualty Insurance Company and affiliates. Potential savings will vary, not available in all states or situations.

Speaker 3 Usually, when a kid encounters a Lego set, they know what to do. Put the driver in the race car, the flamingo in the pond, the astronaut in the spaceship.

Speaker 3 But the Lego set this kid is playing with, it's not so obvious what it is or who goes where.

Speaker 3 It features a lot of random characters. Chef, painter, a robot, a knight.

Speaker 3 The kid picks up the knight, turns him over, and pops off the helmet.

Speaker 3

Also bald. He sticks the pirate behind one of the desks.

That's where the lawyers would sit. He tries the knight at the witness stand and the robot on one seat that's higher than all the rest.

Speaker 3 That is where the judge would sit.

Speaker 5 It's really cute, but this is exactly what an immigration court would look like. So the stenographer would be there, and that's where they have to go and talk.

Speaker 3 And so that's where the judge comes from. This is Asia Sarwari, managing attorney at the Atlanta Office of the International Rescue Committee, or IRC.

Speaker 3 She and her staff built this Lego court as a makeshift solution to an impossible problem. How do you explain to a six-year-old what immigration court is?

Speaker 5 I mean, immigration court is frightening for everybody across the board, adults and kids, but this is a way for the kids to understand that this is a time for them to be able to tell their story and also to just give them some comfort.

Speaker 5 It really calms the kids down because when they go to court, then they're like, oh, okay, this is where the judge sits. This is where I sit, sort of thing.

Speaker 3

I'm Hannah Rosen. This is Radio Atlantic.

Today, Trump's immigration policy meets a six-year-old boy. Many of you listening might remember the phrase family separation from Trump's first term.

Speaker 3 Images of babies being torn from their mother's arms, hysterical parents, children in what look like cages.

Speaker 3 We haven't seen a spectacle like that yet, mainly because there aren't as many families crossing at the border. But that doesn't mean that things are any better for unaccompanied minors.

Speaker 3 This time around, the Trump administration is going after special protections for these kids, protections that have been carved out over the last decade.

Speaker 7 The United States government, you know, by and large, takes care of children and affords them a special treatment regardless of how they enter the country, even if they enter illegally.

Speaker 3 That's Nick Miroff, an Atlantic staff writer who covers immigration.

Speaker 7 There was no need for them to try to evade capture by the U.S. Border Patrol.

Speaker 7 As minors, they could simply cross over and seek out the first Border Patrol agent they could find, turn themselves in, and knowingly be treated differently than other illegal border crossers.

Speaker 7 Because there have been some very horrible cases of deaths of children in U.S.

Speaker 7 Border Patrol custody, Border Patrol agents who are effectively border cops know that they have to be careful and handle these children with sensitivity, and they generally do.

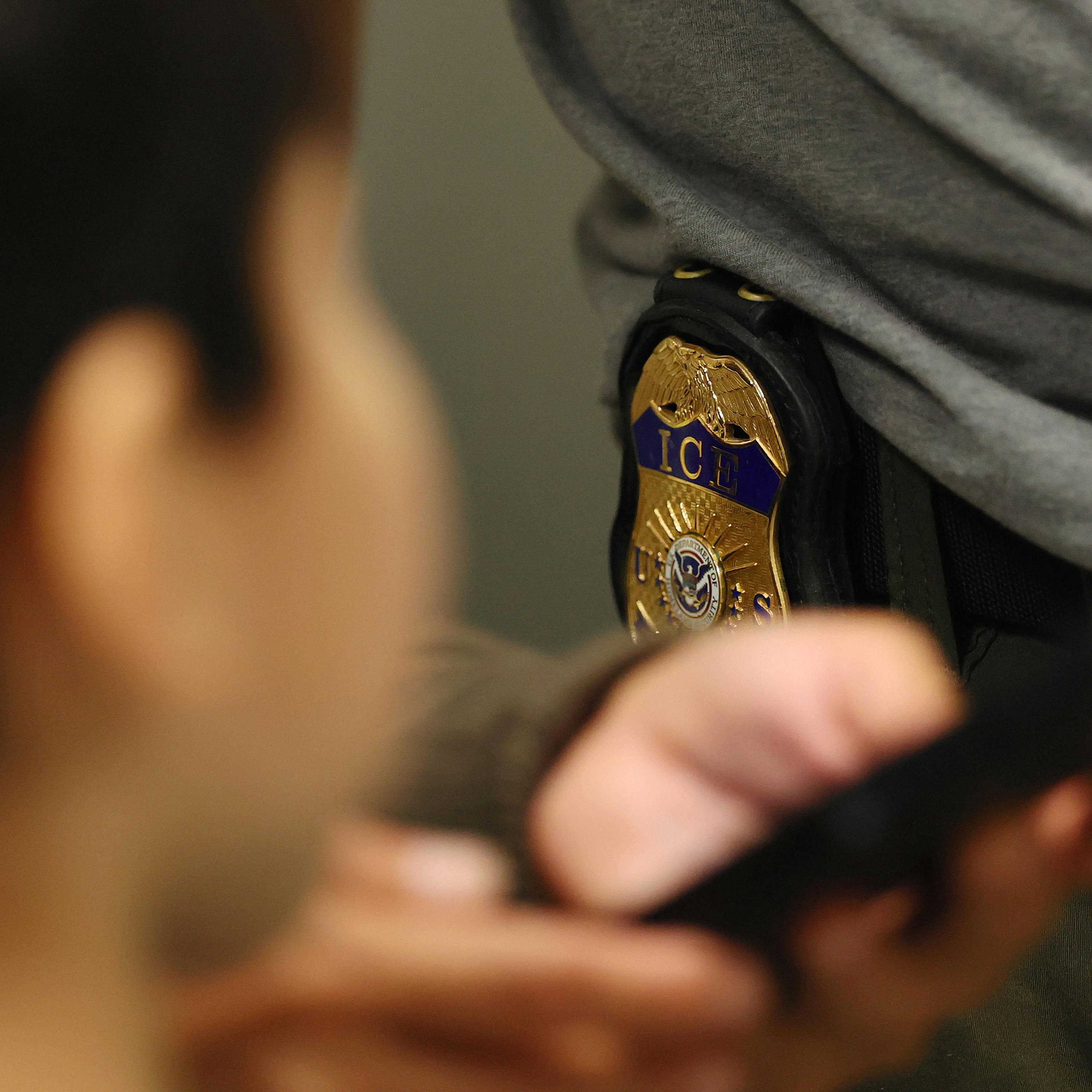

Speaker 3 The way the system is currently set up, children who cross the border without a parent find their way to a border patrol agent who then quickly turns them over to another agency called the Office of Refugee Resettlement, or ORR.

Speaker 3 ORR tries to place them quickly with a sponsor who's typically a relative. ORR is part of health and human services, the idea being to keep minors out of the ICE system.

Speaker 3 Or that was the idea before the Trump administration.

Speaker 7 They have for the longest time wanted to kind of break down that firewall firewall between ICE, Immigration and Customs Enforcement, which is looking to arrest and deport immigrants who are here illegally, and Health and Human Services, whose mandate is to take good care of these kids, make sure nothing happens to them, get them to sponsors safely.

Speaker 7 You know, it's a pivot toward an all-out kind of enforcement-only oriented model whose goal is to, you know, carry out the president's mass deportation campaign and to really to break up the model that has been in place for much of the past 10 years.

Speaker 3 What specifically are they doing to break up the model?

Speaker 7 They have stripped the funding for the legal aid organizations that represent children and minors in federal custody and have worked with them.

Speaker 7 You know, they've just really deprived the system of resources.

Speaker 3 One of those was the non-profit that funds OSIA's office.

Speaker 3 Earlier this year, as part of an executive order titled, Protecting the American People Against Invasion, funding was cut and these legal service providers received a stop work order, which would have affected about 26,000 kids.

Speaker 7 You know, conservatives have been very adamant that federal tax dollars should not go to defend and advocate for illegal immigrants and to help them get funding to stay in the United States.

Speaker 3 Legal aid groups went to court, citing a law passed by Congress in 2008 creating certain protections for unaccompanied minors.

Speaker 3 A federal judge in California ordered the funding temporarily restored until a final judgment expected in September.

Speaker 5 If it happens again or if the litigation doesn't work the way we want it to, it's going to be very difficult to help these kids.

Speaker 3 What percent of your funding is this government funding?

Speaker 5 99.9%.

Speaker 3 Okay, yeah, that's a lot.

Speaker 5 We do have some private backing, but the needs are so great that it's just not feasible to move forward without programmatic funding.

Speaker 7 There aren't the resources to hire lawyers for every single person that comes across and makes a claim.

Speaker 7 We're talking about hundreds of thousands of unaccompanied minors just in the Biden administration.

Speaker 3

The Trump administration has said that it wants to save money. Another reason to cut the funding might be that it's effective.

It increases the chance that the kids get legal status.

Speaker 5 If a person has a lawyer, they're five times more likely to win their immigration case.

Speaker 5 So these kids qualify for legal status. They just need someone to guide them on the path.

Speaker 3 And just to clarify, five times as likely does not add up to likely. How hard is it to get asylum? Like what percent of people who apply for asylum get asylum?

Speaker 5 Well, for immigration court in Atlanta, it's less than 2% approved.

Speaker 3 Oh. It's really hard.

Speaker 5 Yes. And so nationwide, if a person does not have an immigration attorney, they're five times more likely to lose.

Speaker 3

Asylum is a many-step process. It can take years and years.

And all of it is predicated on proving convincingly that you've been persecuted in your own country.

Speaker 5 We do have kids who have physical scars of what happened to them, why they had to flee their home country.

Speaker 5 You know, we have kids who were beaten by military in their home country because of who they're affiliated with or who their parents or extended families are affiliated with.

Speaker 5 I mean, just for example, we had a 14-year-old who had a six-week old child, and that's because she was fleeing extreme danger in her home country, and then she was assaulted on the way over.

Speaker 5 So that's the type of cruelty that our clients are facing. We really do see some graphic signs of violence and abuse.

Speaker 3 Absent the obvious signs, the lawyers have to find a way to get kids to describe what they've been through.

Speaker 5 So we just, you know, try to get some information from the kids.

Speaker 5 And we had a little four-year-old who every time we asked her just some basic questions but she would get scared and turn off the lights and hide under the table and so then she had a little fake phone and so she would hand the phone to the little girl and ask the questions and go back and forth but a lot of the kids are so they just don't want to discuss what's happened in the past whether they're very young or very you know older so we spend a lot of time to not re-traumatize them

Speaker 3 the majority of the kids who go through the system are pre-teens or teens teens. The boy we met in the office that day crossed the border with his younger sister.

Speaker 3 They were five and two when Asia first met them.

Speaker 5 What was the most difficult, at least for us, was trying to

Speaker 5

talk to them about what happened to them. The little girl couldn't share.

any information, of course, because she was only two years old.

Speaker 5 But the older child, the five-year-old, he was able to express fear, but not exactly what happened.

Speaker 3 Here's what she learned. The family was targeted by gangs and experienced severe violence in their home country.

Speaker 3

They made it to the U.S.-Mexico border, but the situation there became dangerous for the kids. So the mother sent them ahead with a group crossing to the U.S.

She had to wait for her own papers.

Speaker 5 They had to cross in a makeshift raft and they fell into the river and they were fished out.

Speaker 5 And so, you know, the children were

Speaker 5 I keep using the word traumatized, were deeply traumatized, but you could tell from the Office of Refugee Resettlement documents, because usually the kids are pretty calm when it's time for them to take their picture, because there's a little passport photo that's attached.

Speaker 5 And the kids were just crying. You could tell in the photo that they were sobbing in the photo.

Speaker 3 To help kids understand the process and feel safe enough to tell their story, Assie and her staff try to make their Atlanta offices as child-friendly as they can.

Speaker 3 During our visit, the siblings sat in a room full of toys and stuffed animals, including a cow named Bacalola, and they tried very hard to sit still while they received what's called a know your rights presentation.

Speaker 3 An IRC legal assistant talks with them as they squirm on two beanbag chairs. As unaccompanied minors, the brother and sister need to know the basics about their rights and about the legal process.

Speaker 3 But the result is like a surreal kindergarten law school school where little kids are learning about things like attorney-client confidentiality.

Speaker 4 Tenemos un especially

Speaker 4 que siama confidencial dad.

Speaker 8 Oyités.

Speaker 3 Aha.

Speaker 4 Lo puesde sí? Sí. Confidencialidad.

Speaker 4 Lo puedesde sí?

Speaker 5 Si.

Speaker 4 Cortido.

Speaker 4 Muy bien, si, confidencialidad.

Speaker 4 Lo que significas que nos otros siempre tenemos que o tener tu permiso para compartir tu información.

Speaker 3 Being there in the room really underlines how absurd it is to think of kids like this navigating this situation without an attorney. The staffer asks the kids if they remember what a lawyer does.

Speaker 3 The little girl answers, I want vaccalola.

Speaker 4

Te recuerdas lo que hace una vogado. Si.

Si que hace.

Speaker 4 Una.

Speaker 1 U la vaca la.

Speaker 4 Ellos que?

Speaker 3 After the break, how the system isn't just getting defunded, it's being turned against the people it's supposed to help.

Speaker 6 Some tech leaders question whether we're in an AI bubble, but others say the best of what AI has to offer is yet to come.

Speaker 9 Maybe in 10,000 years, AI will be based on physics that we don't even understand right now, and we'll have many different approaches.

Speaker 6 Join us weekly starting October 15th for the most interesting thing in AI, brought to you by Rethink, the Atlantic's creative marketing studio, in collaboration with PwC, wherever you get your podcasts.

Speaker 10

This is an Etsy holiday ad, but you won't hear any sleigh bells or classic carols. Instead, you'll hear something original.

The sound of an Etsy holiday, which sounds like this.

Speaker 10 Now that's special.

Speaker 3 Want to hear it again? Get original and affordable gifts from small shops on Etsy.

Speaker 5 For gifts that say, I get you, shop Etsy.

Speaker 10 Tap the banner to shop now.

Speaker 3

The U.S. immigration system, as it currently stands, has two goals.

One, to manage immigration itself. Who gets to enter the country, when, where, and for how long.

Speaker 3 The other is to ensure the welfare of children that cross the border. Make sure they're not subject to trafficking.

Speaker 3 Bring them to safety, return them to relatives once those relatives have been vetted as so-called sponsors. As Nick Miroff describes, Those two goals are sometimes in tension.

Speaker 7 Up until now, there has existed basically, you know, a firewall between the sponsorship process and immigration enforcement by ICE.

Speaker 7 The idea being that if you have a kid in custody and you're looking for a sponsor in order to get them out of government custody, then you shouldn't have that sponsor fear arrest and deportation by coming forward and saying, I will take custody of this child.

Speaker 3 The idea was to make it as easy as possible for a sponsor to come forward so the child would be safe. But that idea seems to be fading.

Speaker 7 Stephen Miller and the aides around him who are leading this broader immigration crackdown have had in their sites for a long time this system of unaccompanied minors who are crossing the border, going through the sponsorship process, and in many cases are being reunited with their relatives who are already here.

Speaker 7 They view this system as basically a broader kind of trafficking scheme, and they want to attack it at its weak point, so to speak.

Speaker 3 That weak point is reunification, the moment where the government has your child and you have to show proof in order to get them back. Under the Trump administration, the requirements have changed.

Speaker 3 Before, a sponsor might have taken a DNA test to prove they were related to the child.

Speaker 3 Now, though, they're required to take a DNA test, and they also need to prove they're living and working in the U.S.

Speaker 3 legally, which means they have to show an American ID or a foreign passport with proof of entry. It means proof of income, like a letter from an employer.

Speaker 3 The way the Trump administration explains these changes, they are protecting children from being picked up by people who don't have their best interests at heart.

Speaker 3 But there are signs that in practice, these changes are keeping kids from landing in a safe place.

Speaker 3 Our colleague Stephanie McCrummin reported that one family had submitted baby photos, baptism records, text messages, all to try and get their kid back. And all not enough.

Speaker 3 As she reported, the family had been rejected for three months and counting.

Speaker 7 And obviously the concern is that if sponsors are too scared to come forward and take custody of the child, then the child will remain in

Speaker 7 the custody of the government for far longer than they should.

Speaker 3 Just that already appears to be happening.

Speaker 3 It varies from case to case, but the Office of Refugee Resettlement has typically housed an unaccompanied minor for about a month before they're released to a sponsor.

Speaker 3 After Trump took office, the average stay for children released each month started rising. 49 days, 112 days, 217 days, all in facilities never intended to house children for so long.

Speaker 7 As we know, in a lot of these group home settings, it can be very stressful. It's not a good environment for children.

Speaker 7 There's tons of pediatric literature about the impact on the psychology of children to be kept essentially in a kind of government custody in which they're living under very strict rules and they're separated from their loved ones.

Speaker 7 And so

Speaker 7 no one until now has really wanted to prolong this process.

Speaker 7 But I think with this administration, we're seeing a willingness to do that and to really try to deter families from potentially using this route in order to do the kind of phased migration that they are so opposed to.

Speaker 3 For Trump officials who want to slow this pipeline of unaccompanied minors, it's a win-win.

Speaker 3 Either families get their kids and the government gets data they could use to pursue immigration enforcement, or they don't get their kids and the pain of the situation creates deterrence on its own.

Speaker 3 It's a kind of family separation 2.0, one that seems more carefully constructed than the first one.

Speaker 3 Americans aren't regularly regularly seeing children in what look like cages or videos of agents taking babies from their mothers.

Speaker 3 Instead, it uses the system that already exists, and it generally does so away from cameras and microphones.

Speaker 7 You know, preventing them from reuniting is part of an enforcement mindset that is similar to zero-tolerance family separation in that there's a willingness here to, you know, potentially inflict trauma on children to achieve an immigration enforcement purpose or some kind of, you know, deterrence.

Speaker 7 It's not the same thing as physically pulling a child away from its parent at the border, but

Speaker 7 the willingness to leave a child in a group home in the government's custody for weeks and weeks and weeks and scare their parents into not coming to get them is also a very serious thing.

Speaker 3 The White House says they're doing this in the name of child welfare. And children getting exploited is, in fact, a vulnerability of this system.

Speaker 3 In 2023, a New York Times investigation showed that amid a huge influx of unaccompanied minors, many ended up working unsafe jobs in places like factories and slaughterhouses.

Speaker 3 They also showed that in 2021 and 2022, the Office of Refugee Resettlement couldn't reach more than 85,000 children.

Speaker 3 Now, that was during a period when the system was overwhelmed by this huge influx of unaccompanied minors.

Speaker 3 But losing contact like that simply meant they they couldn't easily reach the kids by phone, which could happen for any number of reasons.

Speaker 3 And ultimately, it's maybe not so surprising that a family that got their child back has less reason to pick up when the federal government calls.

Speaker 3 During his campaign, though, Trump spun these statistics into a much more sinister and much more certain story.

Speaker 8

88,000 children are missing. You know, 88,000, think of that.

88,000 children are missing under this administration.

Speaker 3 In a matter of weeks, Trump's number grew.

Speaker 8 The Biden-Harris administration has lost track of an estimated 150,000 children, many of whom have undoubtedly been raped, trafficked, killed, or horribly abused. Think of it.

Speaker 8

150,000 children are missing. 325,000 children are missing.

Many are dead.

Speaker 8 Many are involved in sex operations.

Speaker 8 Many are working as slaves in different parts of probably this country and probably many others.

Speaker 3 Now, in his current immigration crackdown, the administration has leaned into this story as a rationale for how it's treating undocumented minors.

Speaker 5 What's frustrating with that is that I think on both sides, everybody believes that there should be anti-trafficking initiatives. But our program is an anti-trafficking initiative.

Speaker 5 If these kids have a way forward, if they have a legal status, they're less likely to be put in dangerous situations.

Speaker 7 We have seen Tom Homan, the White House Borders R in particular, talking about finding the children.

Speaker 7 He has told me in interviews that this is as much a priority for him as carrying out the president's mass deportation campaign, and that he believes that hundreds of thousands of minors have been trafficked into the United States and may be in danger, and that he wants to mobilize the resources of ICE and the Department of Homeland Security to do essentially wellness checks on this group to make sure that they're not in some kind of danger.

Speaker 7 However, I think that the underlying message of those checks by the authorities is very clear in that

Speaker 7 it's part of this broader effort that they have going to gather information on families living in the United States illegally, who have come across illegally, who have participated in some of these arrangements so that they can take enforcement action against them.

Speaker 3 The wellness checks are done by ICE, but carried out with help from a hodgepodge of law enforcement, including the FBI and even the DEA.

Speaker 3 Asia told us that some clients her team works with have had agents show up at their door.

Speaker 5 What's happening now is there are these wellness checks where people from various law enforcement agencies show up at the sponsors' homes, bang on the doors, they're masked, they don't show any identification, And also the wellness people who are conducting the wellness checks are not contacting us, their attorneys, so we can provide them the information that they need.

Speaker 3 And then, so what is the purpose then, do you think?

Speaker 5 To frighten them, I guess, because we have reached out.

Speaker 5 We've had other clients who have had wellness checks and we've driven out to go speak to whoever is there, but then they're gone by the time we get there and then we leave our information, nobody will contact us.

Speaker 5 There doesn't seem to be any rhyme or reason to them, and it's not making anybody safer. What if it's just some strange person who is not affiliated with law enforcement agencies?

Speaker 5 None of them show any badges, none of them show any official paperwork, they're masked. How are we supposed to know that one person is a law enforcement agent versus a bad actor?

Speaker 3 We're not hiding our clients.

Speaker 5 So it just doesn't seem to result in what they want. It's not really a wellness check.

Speaker 3 About the wellness checks, which the White House officially calls a national child welfare initiative, an iSpokesperson said in a statement, our agents are doing what they should have been doing all along, protecting children.

Speaker 3

I'm trying to think of this from an oppositional point of view. Like if I'm listening to this and thinking, like, why should the U.S.

government provide

Speaker 3 funding for lawyers for people who cross unlawfully?

Speaker 5

Well, I would say this is the overall focus is the kids need help and we're able to provide this help. We're trying to protect children.

But then I also say seeking asylum is a basic human right.

Speaker 5 These kids and their sponsors, their parents or whoever is guiding them, they're trying to do things the right way. Most of them qualify for legal status.

Speaker 5 They just need someone to guide them on the path.

Speaker 3 And when you say doing things the right way, what do you mean? Well, you know,

Speaker 5 I use this phrasing because I've heard this, but

Speaker 5

the right way is that they have presented themselves to the government. They're not hiding.

They are trying to find a legal status.

Speaker 3 I think about this

Speaker 3 often just kind of

Speaker 3 What is the nature of a country that opens itself up for asylum versus the nature of a country that doesn't?

Speaker 3 Like, what decision are you making when you decide, oh, yes, we are a country that's going to, you know, support a process, a legal process through which you can apply for asylum?

Speaker 3 Like, what does that say about you as a country versus a few? Because many countries don't.

Speaker 5 I mean, well, and I also think that if you look at the other countries, they don't have the opportunity. It's not safe there either for them to

Speaker 5 seek asylum. So they really are coming to the first country that they are able to have some semblance of safety.

Speaker 3

In this family's case, that's the country they came to. One where there was a system of protections in place, where they had an attorney to guide them.

A known asylum process, even if not an easy one.

Speaker 3 But now, the game has changed.

Speaker 3

This episode of Radio Atlantic was produced by Kevin Townsend. It was edited by Claudina Bade.

Erica Wong engineered, Rob Smersiak provided original music, and Sarah Krulewski fact-checked.

Speaker 3 Claudina Bade is the executive producer of Atlantic Audio, and Andrea Valdez is our managing editor.

Speaker 3 Listeners, if you like what you hear on Radio Atlantic, you can support our work and the work of all Atlantic journalists when you subscribe to the Atlantic at theatlantic.com/slash listener.

Speaker 3 I'm Hannah Rosen. Thank you for listening.

Speaker 11 This holiday, discover meaningful gifts for everyone on your list at Kay. Not sure where to start? Our jewelry experts are here to help you find or create the perfect gift, in-store or online.

Speaker 11 Book your appointment today and unwrap Love This Season, only at K.