The Cockroach Cure

Learn more about your ad choices. Visit megaphone.fm/adchoices

Press play and read along

Transcript

Speaker 1 and Alyssa are always trying to outdo each other. When Alyssa got a small water bottle, Mike showed up with a four-litre jug.

Speaker 1 When Mike started gardening, Alyssa started beekeeping.

Speaker 2 Oh, come on.

Speaker 1

They called a truce for their holiday and used Expedia Trip Planner to collaborate on all the details of their trip. Once there, Mike still did more laps around the pool.

Whatever.

Speaker 1

You were made to outdo your holidays. We were made to help organize the competition.

Expedia, made to travel.

Speaker 3 Chronic migraine is 15 or more headache days a month, each lasting four hours or more.

Speaker 5 Botox, onobotulinum toxin A, prevents headaches in adults with chronic migraine before they start. It's not for those with 14 or fewer headache days a month.

Speaker 5 It prevents on average eight to nine headache days a month versus six to seven for placebo.

Speaker 6 Prescription Botox is injected by your doctor. Effects of Botox may spread hours to weeks after injection, causing serious symptoms.

Speaker 6 Alert your doctor right away as difficulty swallowing, speaking, breathing, eye problems, or muscle weakness can be signs of a life-threatening condition.

Speaker 6 Patients with these conditions before injection are at highest risk. Side effects may include allergic reactions, neck, and injection, sight pain, fatigue, and headache.

Speaker 6 Allergic reactions can include rash, welts, asthma symptoms, and dizziness. Don't receive Botox if there's a skin infection.

Speaker 6 Tell your doctor your medical history, muscle or nerve conditions, including ALS Lou Gehrig's disease, myasthenia gravis, or Lambert Eaton syndrome, and medications, including botulinum toxins, as these may increase the risk of serious side effects.

Speaker 3 Why wait? Ask your doctor, visit BotoxPronicMigraine.com, or call 1-800-44-BOTOX to learn more.

Speaker 7

This is Radio Atlantic. I'm Hannah Rosen.

A few weeks ago, one of our science editors, Dan Engber, said he had a story to tell me. It's a little weird, definitely gross, but it's amazing.

Here it is.

Speaker 7 We'll first close the door behind you.

Speaker 2

Hey. Hello.

What's up?

Speaker 1 So I have a story about a scientific discovery made in very recent times that no one thought was possible,

Speaker 1 which changed the lives of millions,

Speaker 2 but no one remembers it. Wow, that sounds fake.

Speaker 2 Do you want to tell me what it is? Sure.

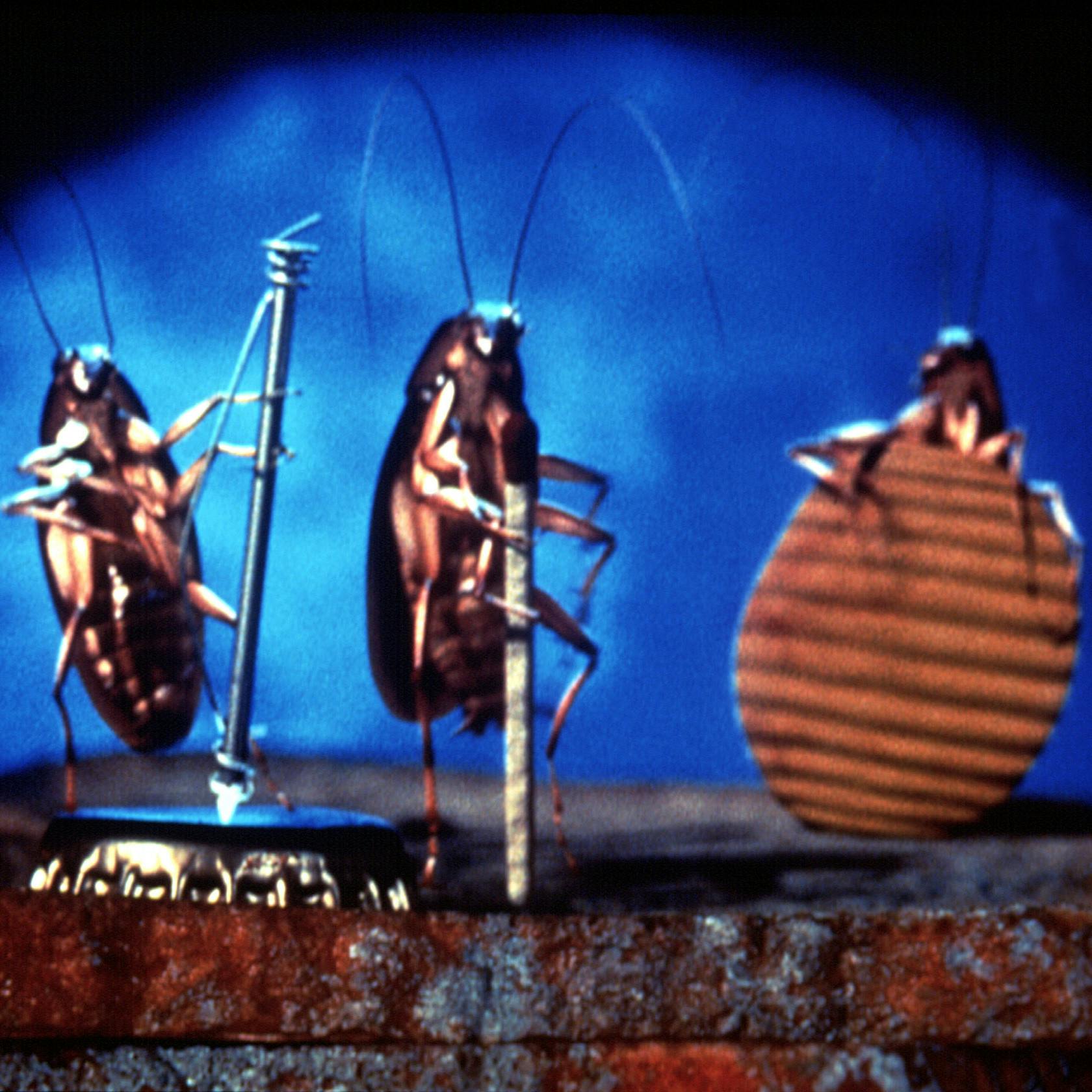

Speaker 1 Well, okay, so this is a story of a forgotten solution, but also of a forgotten problem, and that problem is cockroaches.

Speaker 2 Cockroach?

Speaker 7 What do you mean cockroaches are a forgotten problem? I feel like I saw one recently.

Speaker 1

Right. You saw one, one cockroach.

Yeah. In the 1980s, there were a lot of cockroaches everywhere.

Cockroaches were like a national news story and almost like a public health emergency.

Speaker 1 So there would be articles with various levels of alarmism about how the risk of being hospitalized for childhood asthma was three times higher in kids who were exposed to cockroach infestations.

Speaker 1 There were stories about how cockroaches could carry the polio and yellow fever viruses.

Speaker 2 Okay.

Speaker 7 So cockroach is everywhere, cockroach is bad for your health.

Speaker 1 Cockroach is everywhere, cockroach is bad for your health, cockroaches in the nation's capital.

Speaker 8 Congress certainly has its hands full these days with the deficit, the MX, Central America, and now debugging.

Speaker 1 So this is an NBC nightly news story with Tom Brokoff from the spring of 1985, which is a very important moment in the history of cockroaches.

Speaker 8

It's very serious. The problem, they're in our desks, they're under tables, they're everywhere.

Some members of Congress are trying valiantly to fight back.

Speaker 8 Congressman Al McCandless has installed this black box. It exudes a sexy scent which attracts female roaches, which are then roasted by an electric grill.

Speaker 1 I mean, I think just in that short clip, you hear

Speaker 2 how...

Speaker 1 completely helpless we were to deal with the cockroach problem. We were trying everything.

Speaker 7 Yes, it does have a throw spaghetti at the wall. Like this is the nation's capital and we can't, we don't really have an answer nor is anyone pretending to.

Speaker 7 It's just like they tried this, they tried that.

Speaker 8 Congressman Silvio Conti, dressed to kill today, proclaimed a war on capital cockroaches.

Speaker 8 A company from his home district has donated 35,000 roach traps to the Capitol, but Conti said more help than that is needed.

Speaker 9 And I want to appeal to the President of the United States. I am certain that President Reagan wants to get rid of many troublesome cockroaches who run around the halls of Congress as possible.

Speaker 9 So please join me in this war on the Capitol cockroaches and squash one for the gipper.

Speaker 1 But you know, listening to all this kind of has almost like a dreamy quality for me

Speaker 1 because

Speaker 1

I actually lived through this myself. Like I was a child of the cockroach 80s.

I had cockroaches in my house all over the place too. And it's almost like hard to remember how pervasive they were.

Speaker 1 So I grew up in New York City.

Speaker 2 Where?

Speaker 1 In Morningside Heights.

Speaker 2 In an apartment.

Speaker 1

In an apartment. Okay.

So middle-class families in the 1980s in New York City had a lot of cockroaches, as I can say from personal experience.

Speaker 1 Just a number of cockroaches that I think is unimaginable to

Speaker 1 younger people, to my my younger colleagues here at the Atlantic?

Speaker 7 Against my

Speaker 7 really like every fiber of my being, I'm going to say, paint me a picture.

Speaker 1 They'd be all over the place all the time, like in full view in day, in night. Certainly if you went into the kitchen at night and turned on the light, they would scatter.

Speaker 1 It wouldn't be like you'd see individual insects. You'd see like a wave pattern.

Speaker 1 You and your brother, let's say, might be taking the Cheerios out of the cabinet and open it up and pour into the bowl, and cockroaches would come out with the Cheerios,

Speaker 1 which

Speaker 1 I think sounds really terrifying to today's New Yorker. But at the time, it was just like time to get a new box of Cheerios.

Speaker 1 There's really this feeling that it was like

Speaker 1 a natural phenomenon, like an endless sense of being enveloped in roaches, like it was an atmosphere of roaches

Speaker 1 or an ocean.

Speaker 1 You're speechless.

Speaker 7 Actually, just to weigh in, I do 100% relate.

Speaker 7

I grew up in an apartment building in Queens and exactly your memory. Like the only difference is it was cornflakes and not Cheerios, but they were everywhere.

Although, you know, it's weird.

Speaker 7 I can't seem to remember if they freaked me out or not. Like, what, did they freak you out? Like, did you scream when you saw cockroaches or call for your mommy?

Speaker 1 Or, like, what did you do?

Speaker 1 So, I don't think we were that squeamish about them. In fact, I know we weren't squeamish because the other thing I remember vividly was my brother and I would play with the cockroaches.

Speaker 1 We would use our wooden blocks and build like obstacle courses, sort of, and try to do cockroach Olympics.

Speaker 7 Did you actually touch them with your fingers?

Speaker 1 I mean, it's kind of hard to imagine that I didn't, but it must be the case. I mean, like I said, it's it, there's sort of a dreamy quality to all this where I almost doubt my own memories.

Speaker 1

And so just to do kind of a gut check, I wanted to call my brother. Okay.

First of all, did we have cockroaches in our apartment growing up?

Speaker 1 We

Speaker 10 had a lot of cockroaches in our apartment growing up. And I, being a little bit older than you, remember it extremely clearly, but it still seems somewhat fantastical,

Speaker 10 the prevalence of cockroaches in our life.

Speaker 1 Okay, so first I asked him about the cereal.

Speaker 2 Okay.

Speaker 10 I loved rice krispies.

Speaker 10 And they used to have like a slightly over-toasted rice krispie that was like a darker brown.

Speaker 1 Yeah, the occasional brown one.

Speaker 10 The brown one.

Speaker 10 And

Speaker 10 I definitely remember a lot of arguments about whether

Speaker 10 something

Speaker 10 was a over-toasted rice krispie, a small over-toasted rice krispie, krispie, or a roach duty. And we would frequently have these arguments.

Speaker 7 He's like completely chill about the roach duty for breakfast situation.

Speaker 1 If only it was just the rice krispies, Anna.

Speaker 10 We had these special medicine cups. They were sort of like plastic hollow spoons.

Speaker 10 And I remember one time

Speaker 10 mom poured the whatever it was, probably

Speaker 10 dimetap or something like that, in, and I saw something swimming in it.

Speaker 10

And I'm like, there's a roach in there. I swear there's a roach in there.

And then she held it up to the light and there was nothing in there.

Speaker 10 I didn't want to take it.

Speaker 10

Finally she convinced me. I drank the whole thing.

I felt the roach crawling around all over my mouth.

Speaker 10 And I spit it all into the sink.

Speaker 10 And she said, oh, there was a roach in it.

Speaker 10 Roaches were just everywhere in our lives. So if we were constantly like throwing out something just because a few roaches walked over it, we wouldn't have anything.

Speaker 1

So that's how we lived. But here's the important part from that conversation with Ben.

Do you remember if that was in apartment 44? I forget when we moved from apartment 44 to apartment 44.

Speaker 2 That was after.

Speaker 10 No, that was all... That was after it was solved, because we moved when I was

Speaker 10 12 or 13, and it was done by then.

Speaker 1 You said that by that time the cockroach problem was solved.

Speaker 1 What's your memory of the solving of the problem in our home?

Speaker 10 Very simple.

Speaker 1 Combat.

Speaker 1 So remember when I told you that the problem we forgot was roaches?

Speaker 7 Yeah.

Speaker 1 This is the solution we forgot.

Speaker 7 Combat. Wait, you mean the combat roach trap, like that little plastic disc where the roaches go in and then they die or something? Like, like that's what this is about?

Speaker 1 Yes.

Speaker 1 That is the amazing American invention that we have all forgotten.

Speaker 7 The thing that sits in aisle 13 on the top shelf, that's the amazing invention.

Speaker 1 The thing that should be sitting in a museum.

Speaker 1

The people who invented combat... are American heroes.

They did something. I mean, you have to think about the fact that the cockroach was and is a symbol of indestructibility, right?

Speaker 1 This is the animal that's going to outlive us after a nuclear war.

Speaker 1 This isn't, if you've ever seen WALL-E, it's a post-apocalyptic Earth. All that's left is a robot and a cockroach.

Speaker 1 It's the animal that cannot be killed. And then in the 1980s, we did it.

Speaker 1 I think it's fair to say we solved the problem. And I don't mean solved it completely and eliminated cockroaches forever, but really took a huge problem and made it much smaller.

Speaker 1 And that wasn't just true in my apartment, but across the country. In fact, I found evidence that that is exactly what happened.

Speaker 1 And so

Speaker 1 I just was fascinated by the question of who did that and what it means that we don't even really fully remember that it happened.

Speaker 7 Wait, there's a who? Like there's a person who did that?

Speaker 2 Yeah.

Speaker 1 Let me introduce you to a very important figure in the history of cockroaches

Speaker 1 who has a catchphrase, and his catchphrase is always bet on the roach.

Speaker 1 He's a member of the Pest Management Hall of Fame. Are you familiar with Pi Chi Omega? The fraternal organization dedicated to furthering the science of pest control.

Speaker 1 They have an annual scholarship called the Dr. Austin Frischman Scholarship.

Speaker 7 Wait, are we going to hear from Austin Frischman himself?

Speaker 2

Dr. Cockroach.

Wow. Okay.

Hello.

Speaker 1

Hi, Dr. Frishman.

Speaking. Hi.

My name's Dan Angles. And so I'm a student.

I got him on the line, and he turns out to be sort of like

Speaker 1 a cockroach mystic almost.

Speaker 7 What is that?

Speaker 1 Just any question you ask, you might get an answer like this.

Speaker 1 I want you to picture. a landfill.

Speaker 1

It's snowing. It's about 28 degrees out.

Okay.

Speaker 1 And you're there with seven or eight men, and you're digging away at the snow because you're teaching them how to bait on a landfill.

Speaker 1 All right.

Speaker 1 And then out of the snow, in that cold, comes American roaches running up, bubbling up, 5, 10, 15, 60, 100, 200

Speaker 1 from the smoldering heat down below.

Speaker 7

I just love this man. He makes it seem like biblical.

So, okay, so where does this cockroach mystic, Dr. Frischman, fit into the story?

Speaker 1 So Frischman is in this story almost from the very start. In 1985 and in the lead up to 1985, Frishman had been hired by a company called American Cyanamid.

Speaker 1 And American Cyanamid researchers had had this product that they were selling for use in controlling fire ants.

Speaker 1 And the researchers were aware of the fact that this fire ant poison worked on cockroaches. And in fact, they used it in the lab to control cockroaches.

Speaker 7 Their own cockroach, frost. Yes.

Speaker 1 Yeah. They put it in peanut butter and they put it around the lab just so they could continue to do their work on fire ants.

Speaker 1 But then the company was making this effort to try to figure out, well, can we repurpose some of our industrial products for consumer use and so forth?

Speaker 1 So you've got a hot new roach control product. Who do you call?

Speaker 1 Oh. Austin Frischman.

Speaker 7

Yes, Austin Frischman. And I said, well, this is going to be difficult, and it may not work.

And the girl said to me, listen, do you want to do the project or not?

Speaker 12 I said, no, I'll do it, just so you know what we're up against.

Speaker 1

Okay, so everything we had up into that point. were these, you know, these insecticides that we'd just been using for years.

And the roaches had just developed resistance to them.

Speaker 1 Even if you, you know, you killed 99% of them, the ones you didn't kill would have some mutation that protected them, or they'd have a thicker shell or something, a thicker exoskeleton, and they'd survive and reproduce.

Speaker 1 And now your insecticides weren't working anymore.

Speaker 7 Right. So they would just keep outsmarting us.

Speaker 1

Right. And so one of the things, this new product that made it different from the old ones, was it wasn't just a spray that you'd put in the corners.

It was actually a bait.

Speaker 1 That little, the black disc had something in it that sort of like tasted like oatmeal cookie that roaches loved. And they would come in and get it and then take it out.

Speaker 13 We were filming the cockroaches and we found that only 25% of the cockroaches ate the bait, but 100% of the cockroaches would die.

Speaker 1 That's Philip Kaler.

Speaker 2 He's another cockroach expert.

Speaker 1 And what he's talking about here is the fact that like this stuff would kill roaches that hadn't even eaten it.

Speaker 7 Like, what do you mean? How?

Speaker 1 Well, that's what I asked Phil Kaler.

Speaker 13 It was a slow-acting toxicant that allowed transfer to other members of the colony.

Speaker 1 They would regurgitate it, or how does it get transferred?

Speaker 13 Well, there are several mechanisms of transfer. The main one would be that cockroaches will eat another cockroach's poop.

Speaker 13 It was actually after this work with combat baits that it became known that cockroaches actually feed poop to their young.

Speaker 7 Amazing. I love it when researchers are put in a position where they have to say words like poop,

Speaker 7 which is very seriously.

Speaker 13 And there are actually other methods of transfer of toxicant as well.

Speaker 13 There is, like you said, regurgitation, where they get sick and they regurgitate some, and other cockroaches will come and feed on that vomit.

Speaker 13 There's also cannibalism, where

Speaker 13 a cockroach will attack another cockroach and eat it. And there's also necrophagy where the cockroaches will eat the dead.

Speaker 7 Each method more charming than the other.

Speaker 2 Yeah. Okay.

Speaker 1 Vomit, poop, or cannibalism.

Speaker 7

This seems exciting. No, I mean, if I were them, this would be really exciting.

Like, I'm just imagining them, you know, like an Oppenheimer, sort of

Speaker 7 sitting in their lab, like figuring out every element of this and how are we not going to, you know, how are we going to make it safe? How's it going to work? It's exciting. Yeah.

Speaker 1 they were on the verge of something big.

Speaker 1 We would run to the lab early in the morning to see the results from the night before or stay up half the night and watch.

Speaker 12 And we began to see, you know, what was happening. In the beginning, I was hesitant in the whole thing, but as we began to do the work and I saw the results first in the lab,

Speaker 12 it was a breakthrough. Okay.

Speaker 1 So Frischman was among the first to take this breakthrough product, put it in a syringe, take it out of the lab, and start using it in restaurants, diners, to see if it worked. And I went into a small

Speaker 1 diner, a little luncheonette place,

Speaker 1

and a bunch of guys were sitting and eating sandwiches. And I was behind the counter, so I was down low.

And I

Speaker 1 had the bait, and I saw the roaches in a crack, and I just put a little tab.

Speaker 1 As I went to go do it, the roaches started coming out and they were

Speaker 1 gobbling it up.

Speaker 1 And I saw in real time them come to the bait.

Speaker 2 I was the first person in the world.

Speaker 12 I was shaking. Okay.

Speaker 12 I'm telling you, I was shaking. I still have that syringe, that original one.

Speaker 1 This is the moment.

Speaker 1

This is the brink of the relatively roach-free world that we live in today. Now we had the little black discs.

I would say

Speaker 1 two inches across or something.

Speaker 7 With an entrance?

Speaker 2 With an entrance.

Speaker 1 With an entrance and an exit.

Speaker 12 I had written a book called the Cockroach Combat Manual.

Speaker 2 So that's how it got its name.

Speaker 1 And Frishman is going to take this product on the road. People would write in

Speaker 1 horror stories, and they won a prize, the product, and me.

Speaker 12 And we would go into those places and knock out the population.

Speaker 1

So he takes this to Texas. He takes this to Georgia.

They do an event at the Museum of Natural History in New York City. They go to the Capitol.

Remember the Tom Brokaw report? Those are combat traps.

Speaker 1 Yeah. And then ads start appearing on television.

Speaker 14 Combat discs. Use roaches to kill roaches.

Speaker 15 I had roaches in my cereal.

Speaker 16 Put combat discs where roaches are, in places you wouldn't dare spray.

Speaker 15

Combat works. The roaches are not in my cereal.

They're gone.

Speaker 14 Control roaches where they live.

Speaker 2 Combat.

Speaker 14 Because where they live is where they dunk.

Speaker 1 So this wasn't just a marketing campaign. I mean, the product really did work.

Speaker 7 What do you mean it worked?

Speaker 1 Well, cockroach numbers were going down.

Speaker 1 You can find signs everywhere.

Speaker 1 Actually, a guy I went to high school with wrote an article for the New York Times in 2004, and he reported that a, there had been a survey of federal buildings and their cockroach complaints between 1988 and 1999.

Speaker 1 So this is combat rollout era. And the number of complaints fell by 93%.

Speaker 1 Wow. I also found a 1991 story from the New York Times, again, right in that combat zone.

Speaker 1 And a New York City housing official is quoted as saying, There was a time when people were horrified at roaches running rampant. And now everybody keeps saying, where did they go to?

Speaker 7

So it's a thing. It's like an actual documented thing.

Yeah. And yet it's not a huge moment.

Like there aren't a lot of stories saying, yay us, we've conquered the cockroach problem.

Speaker 2 No, there are not.

Speaker 1 There are stories about combat success as a almost like a business case study.

Speaker 1 There are stories that remark upon the fact that there are fewer cockroaches than there used to be.

Speaker 7 But nothing that's like, this enormous giant urban problem has finally been solved by this ragtag crew of amazing scientists.

Speaker 1 Nothing of that nature. There's a reason why I had to introduce Austin Frischman to you as a member of the Pest Management Hall of Fame.

Speaker 1 And you weren't like, oh, you mean the guy in the back of the quarter?

Speaker 2 Yeah.

Speaker 7 Right.

Speaker 7 Right. But

Speaker 7 why?

Speaker 1 I mean, that is the question that has been keeping me up at night. And I have some ideas.

Speaker 11 This episode is brought to you by Progressive Insurance. Do you ever find yourself playing the budgeting game?

Speaker 11 Well, with the name Your Price tool from Progressive, you can find options that fit your budget and potentially lower your bills. Try it at Progressive.com.

Speaker 11

Progressive Casualty Insurance Company and Affiliates. Price and coverage match limited by state law.

Not available in all states.

Speaker 17 At blinds.com, it's not just about window treatments. It's about you, your style, your space, your way.

Speaker 17 Whether you DIY or want the pros to handle it all, you'll have the confidence of knowing it's done right.

Speaker 17 From free expert design help to our 100% satisfaction guarantee, everything we do is made to fit your life and your windows. Because at blinds.com, the only thing we treat better than windows is you.

Speaker 17 Visit blinds.com now for up to 50% off with minimum purchase plus a professional measure at no cost. Rules and restrictions apply.

Speaker 7 Dan, you said you had some ideas about why this discovery didn't get the credit and hoopla that it deserved.

Speaker 1 So my brother had a good theory about this. I said, well, how come we, we just are family? Why didn't we celebrate and like go out to dinner or something? The roaches are gone.

Speaker 1 And he said, Well, it's because we just assumed they would come back.

Speaker 1

So, I think it was that must be part of it, right? That there was like, oh, this new thing works, but like, yeah, everything works the first time you do it. Right.

So, there was never one moment

Speaker 1 where you realized that the world had changed.

Speaker 1 Or it could be that, you know, when things change for the better, we just have a tendency to just accept, you know, the new, better reality and pretend the old thing didn't happen.

Speaker 1 Like, hey, that's done. I'd rather not discuss it.

Speaker 7 Like, what's an example of that?

Speaker 1 Like the Spanish flu, for example.

Speaker 2 There's a

Speaker 1

famous gap in art and literature about the Spanish flu. There is not a great literature of this cataclysmic event in the 19 teens.

You'd think there would be, but there isn't. Why not?

Speaker 7 Probably because it was traumatic. And actually, you know, I think that's similar to the experience with cockroaches because when,

Speaker 7 at least in my memory, when I was living with them, it wasn't just like kind of gross or annoying or an inconvenience. It's really unsettling.

Speaker 7 Like it lives as this constant undercurrent of anxiety and a sense that you just don't have control over things. It's like a terrible feeling.

Speaker 1 Like a free-floating, pervasive anxiety hanging over you at all times.

Speaker 2 Yes.

Speaker 1 Yes. Can we talk about the Cold War for a second?

Speaker 7 Yeah.

Speaker 2 Yeah.

Speaker 2 Yeah.

Speaker 1 So we were talking about how the cockroach was this symbol of indestructibility that would outlast us in the event of nuclear war.

Speaker 2 Yeah.

Speaker 1 This was, I mean, the cockroach was in a way a symbol of the Cold War. Like the

Speaker 1 nuclear disarmament groups would put ads in the newspaper with just a picture of a cockroach to try to be like, wake up, America, we have to disarm now, or this is the future.

Speaker 7 So it all just got blended in our heads, like nuclear war anxiety, cockroach anxiety.

Speaker 1

Yes. And then those two anxieties were being unwound at almost exactly the same time.

I mean, just to be frank, this is a highly tenuous theory, but I do want to line these things up.

Speaker 1 So, you know, 1985, the Tom Brokaw report, the combat is coming out, you know, spring of 1985, that's also when Mikhail Gorbachev comes to power.

Speaker 1 In fact,

Speaker 1 Silvio Conti, the congressman who on the steps of the Capitol is saying squash one for the Gipper,

Speaker 1 touting combat traps which are manufactured in his district. Five days later, he's in Moscow.

Speaker 1 for a historic meeting with Gorbachev at the Kremlin that is considered a watershed moment in the wind down of the Cold War.

Speaker 16 Gorbachev says at the present time, relationships are in an ice age. However, he said spring is a time of renewal.

Speaker 1 I'm just saying the guy wearing the exterminator outfit on the steps of the Capitol, touting combat, gave Ronald Reagan the advice. to meet with Mikhail Gorbachev.

Speaker 7 Like

Speaker 7 in the span of a week?

Speaker 1 In less than a week. In less than a week,

Speaker 1 he was in Moscow.

Speaker 1 And you start to see combat traps are

Speaker 1 spreading through the country as glasnost is spreading through the USSR.

Speaker 1 And in the years that follow,

Speaker 1 we have the fall of the Berlin Wall and the collapse of the Soviet Union.

Speaker 1 Those are exactly the years when the cockroach populations are finally diminishing, when we're winning the war on cockroaches and we're winning the Cold War. It's happening concurrently.

Speaker 7 So what you're saying is our nuclear fears dissipate. Our cockroach fears dissipate.

Speaker 2 And what?

Speaker 1 What I'm saying is it was the cockroach that took over the imagination as this thing. So they made sense to stand in for nuclear fears.

Speaker 1 Going the other way, once we were free of that nuclear anxiety, we just sort of glided into a roach-free world.

Speaker 1 Okay, Hannah, there's one more thing.

Speaker 1 So the roaches are coming back.

Speaker 2 No.

Speaker 1 Yes, I'm sorry to say.

Speaker 2 What?

Speaker 1 It seems clear that the roaches are coming back, but it has taken a really long time, right?

Speaker 1 So that it's true that the poison, they couldn't develop biological resistance to the poison, but then roaches did develop what's called a behavioral resistance to the baits.

Speaker 1 Basically, roaches stopped preferring sweet foods.

Speaker 1 So the poison would still kill them, but they weren't interested in the oatmeal cookie bait in the center of the combat trap. So roach numbers are slowly going up again.

Speaker 1 And if you read publications of the Pest Management Association newsletter, which maybe I've done recently, you can see that there's, you know, there's some chatter about how roach calls are increasing.

Speaker 1

So I pulled some numbers. I went to the American Housing Survey from the federal government.

In 2011,

Speaker 1 13.1 million estimated households had signs of cockroaches in the last 12 months. In 2021, 14.5 million.

Speaker 1 So

Speaker 1

creeping. That's the word.

Creeping. The numbers are creeping upward.

Speaker 7 Does that raise the possibility that future generations, my children, their children will actually have to contend with roaches?

Speaker 2 They might.

Speaker 1 It's possible.

Speaker 1 But

Speaker 1 I'd be lying if I didn't say it's also

Speaker 1 a little bit appealing in a way?

Speaker 7

No. I mean, no.

Did you say appealing?

Speaker 2 Well,

Speaker 2 okay.

Speaker 1 This came up when I was talking to my brother. What's the attitude of your children towards cockroaches?

Speaker 10 My children are total wusses about it.

Speaker 1 Right.

Speaker 10 They run away and they scream.

Speaker 10 Shosh is terrified of insects, but...

Speaker 1 Is she better or worse for that?

Speaker 10 I would say she's worse for that.

Speaker 7 I mean, isn't that what everyone says? Like, we were the toughest generation and everything has gone downhill since then.

Speaker 7 I mean, I feel that there's a little bit of that in this conversation we're having.

Speaker 1 Yes, that is exactly the conversation we're having.

Speaker 1

And it's embarrassing, but true. I can't shake it.

Like, I have some pride in the fact that we did the Roach Olympics.

Speaker 1

I don't, that it might be a ridiculous thing to be proud of, but I feel like it was we were being imaginative and fearless and having fun. My kids are imaginative and have fun.

They are not fearless.

Speaker 10 Falling to pieces at the sight of an insect

Speaker 10 does not strike me as a healthy way to attack life.

Speaker 10 As a species,

Speaker 10 We would not have made it very far if just a little filth took us out. And

Speaker 10 maybe the roachy upbringing

Speaker 10 is what instilled that in me.

Speaker 1 So you're pro-roach.

Speaker 1 Mom has been vindicated for feeding you a roach in medicine.

Speaker 11 Oh, yeah. Mom is absolutely vindicated.

Speaker 7 So the thing you're actually nostalgic for is this both freedom and maybe even a little bit of courage.

Speaker 1 Yeah, but you know, it's more than that. Not only did my brother and I get to enjoy the feeling of being unafraid of cockroaches, we also got to enjoy the feeling of things getting better.

Speaker 1

Yeah. An intractable problem gets solved.

And I feel like that's, you know, that's a really nice lesson to learn even as a kid.

Speaker 1 And unfortunately, I don't, I don't know that my kids have had many opportunities to learn that specific lesson. So I'm nostalgic for that too.

Speaker 2 You know what, Dan?

Speaker 7 Yeah.

Speaker 7 I think that it's time that me and you and your brother go and have our celebratory dinner that we never had all those years ago. Like instead of going to a steakhouse,

Speaker 7 we'll just each get bowls of cereal. Be bowls of cereal for everyone.

Speaker 1 Rice krispies. Yeah.

Speaker 7 This episode of Radio Atlantic was produced by Ethan Brooks. It was edited by Jocelyn Frank, fact-checked by Michelle Soraka, and engineered by Rob Smirciak.

Speaker 7

Special thanks to Sam Schechner for his roach reporting in the New York Times. Claudina Bade is the executive producer for Atlantic Audio, and Andrea Valdez is our managing editor.

I'm Hannah Rosen.

Speaker 7 Thanks for listening.