What Up Holmes?

Special thanks to Jenny Lawton, Soren Shade, Kelsey Padgett, Mahyad Tousi and Soroush Vosughi.LATERAL CUTS:Content WarningFacebook Supreme CourtThe Trust EngineersEPISODE CREDITS: Reported by - Latif NasserProduced by - Sarah Qariwith help from - Anisa Vietze

Signup for our newsletter!! It includes short essays, recommendations, and details about other ways to interact with the show. Sign up (https://radiolab.org/newsletter)!

Radiolab is supported by listeners like you. Support Radiolab by becoming a member of The Lab (https://members.radiolab.org/) today.

Follow our show on Instagram, Twitter and Facebook @radiolab, and share your thoughts with us by emailing radiolab@wnyc.org.

Leadership support for Radiolab’s science programming is provided by the Simons Foundation and the John Templeton Foundation. Foundational support for Radiolab was provided by the Alfred P. Sloan Foundation.

Press play and read along

Transcript

Speaker 1 WNYC Studios is supported by ATT.

Speaker 1 Hearing a voice can change everything, so ATT wants everyone to gift their voice to loved ones this holiday season, because that convo is a chance to say something you'll hear forever.

Speaker 1 ATT, Connecting Changes Everything.

Speaker 2 I'm Alex.

Speaker 3 I have osteogenesis imperfecta. Most people know it as brittle bonus disease.

Speaker 4 Shriner's Children's provides specialized care to kids who need it most. Your donations make all the difference.

Speaker 5

I honestly have lost track of how many surgeries Alex has had. Without Shriners' Children's, there'd be so many kids that would go unhelped.

They really are a family.

Speaker 4 Go online to love shriners.org to give now. Thank you.

Speaker 2 Hear that?

Speaker 6 That's me in Tokyo learning to make sushi from a master.

Speaker 7 How did I get here?

Speaker 6 I invested wisely.

Speaker 7 Now the only thing I worry about is using too much wasabi.

Speaker 6 Get where you're going with SPY, the world's most traded ETF. Getting there starts here with State Street Investment Management.

Speaker 8

Before investing, consider the funds' investment objectives, risks, charges, and expenses. Visit state street.com/slash I am for prospectus containing this and other information.

Read it carefully.

Speaker 8

SPY is subject to risks similar to those of stocks. All ETFs are subject to risk, including possible loss of principal.

Alps Distributors Inc. Distributor.

Speaker 7 Wait, you're listening.

Speaker 2 You are listening

Speaker 2 to Radio Lab.

Speaker 2 Radio Lab from

Speaker 2 WNYC.

Speaker 2 Hey, it's Lothiff. This is Radio Lab.

Speaker 2 So just last week here on the show, we had a conversation between our own Simon Adler and law professor Kate Klonick, talking about how the idea of free speech in this country is playing out and often not playing out online.

Speaker 2 right now.

Speaker 2 But

Speaker 2 these questions of free speech in the United States go back literally to the beginning. It's the First Amendment for crying out loud.

Speaker 2 And as we argue over what people should be seeing on these apps, on social media apps, it took me back to a story we did a couple years ago that feels like it gets to the origin of the modern notion of free speech.

Speaker 2 In particular, the idea that there should be an open marketplace of ideas, right?

Speaker 2 That's the reason any of these social media platforms are allowed to be as wild as they are, because they are theoretically open marketplaces of ideas.

Speaker 2 And as I told our then host, Jad Abimrod, surprisingly, that whole idea of the marketplace of ideas came from one moment, and even more surprisingly, from one guy.

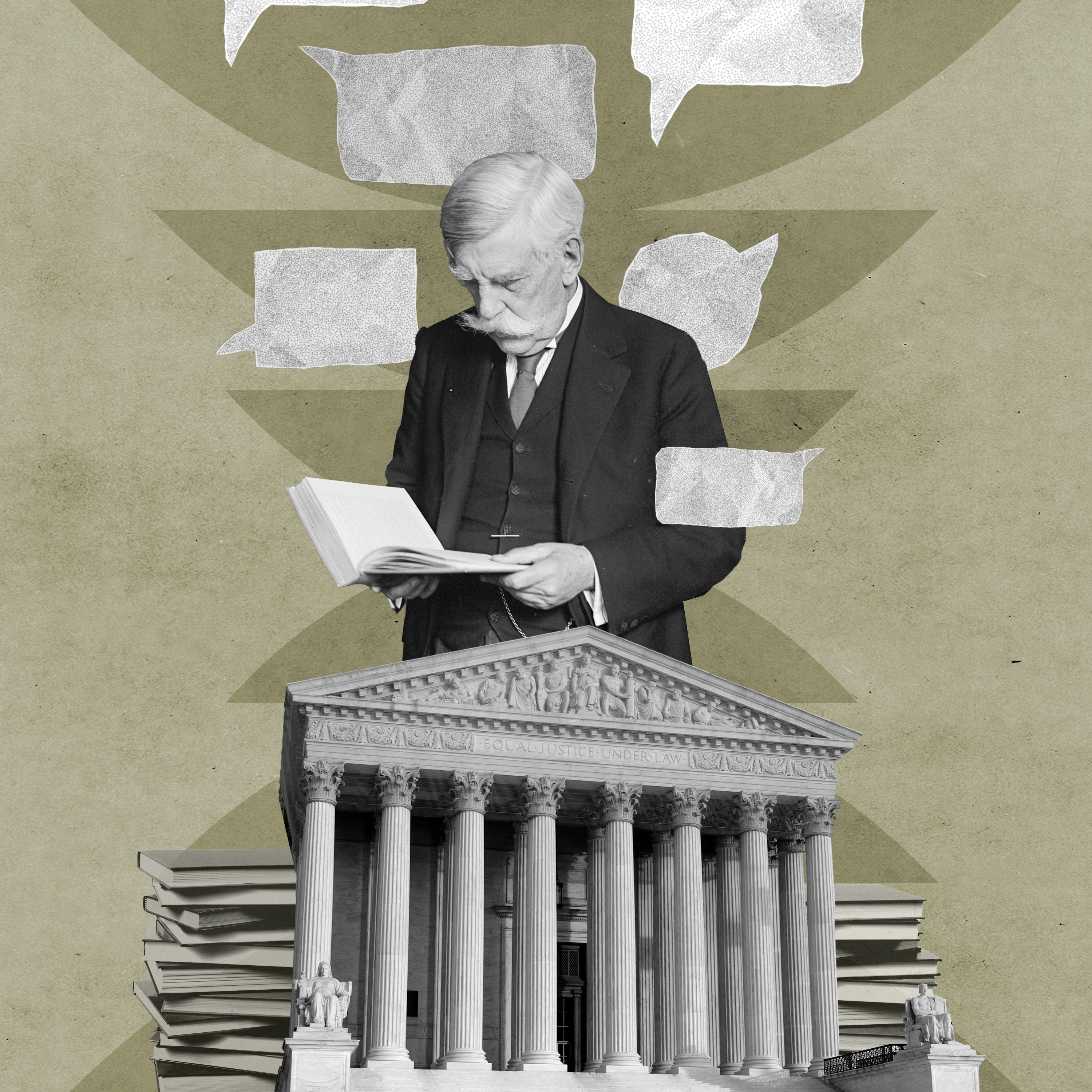

Speaker 2 Oliver Wendell Holmes.

Speaker 10 Magnificent is the word for Oliver Wendell Holmes.

Speaker 7 Regarded today as the greatest Supreme Court justice in our history.

Speaker 2 That story was told to me by this guy, Thomas Healy.

Speaker 7 Professor of Law at Seton Hall University School of Law, who wrote a book about Oliver Wendell Holmes. He essentially laid the groundwork for our modern understanding of free speech.

Speaker 2 And, you know, Holmes, he's from this wealthy Boston family, fought in the Civil War on the Union side.

Speaker 2 And by the time he's sitting on the Supreme Court, he's in his 70s and sort of an imposing figure.

Speaker 7 Piercing blue eyes. He had this sort of shock of very thick white hair on his head.

Speaker 11 Mustache, right? He has a great mustache.

Speaker 2 Yes. Great mustache.

Speaker 7 That expanded out past the edges of his face.

Speaker 2 But the most important thing to know about Oliver Wendell Holmes is that he was stridently anti-free speech as we know it today

Speaker 2 until he changed his mind.

Speaker 2

Huh. And it happened.

That switch happened at a very particular moment in his life.

Speaker 2 So

Speaker 2 1917,

Speaker 2 World War I is happening.

Speaker 10 And in Washington, the draft is invoked. President Wilson draws the first number.

Speaker 7 And Congress was worried that if people criticized the draft, then they wouldn't be able to raise an army.

Speaker 2 Congress passed something called the Espionage Act.

Speaker 7 Made it a crime to say things that might obstruct the war effort.

Speaker 2 Part of it had to do with spy stuff, but there was another part that made it a crime to say things.

Speaker 7 Anything that was critical of the form of the United States government or of the president, anything that was disloyal or scurious.

Speaker 2 Which covered pretty much everything.

Speaker 7 It made it a crime to have a conversation about whether the draft was a good idea, about whether the war was a good idea.

Speaker 2 And so all of a sudden, people were getting thrown in jail.

Speaker 7 People who forwarded chain letters that were critical of the war.

Speaker 2 People who gave speeches against the draft.

Speaker 7 Or people who said that the war was being fought to line the pockets of J.P. Morgan.

Speaker 2 And several of these cases actually made it all the way up to the Supreme Court.

Speaker 2 So, in March 1919, three different cases come up in quick succession: Schenk versus United States, Froerk versus United States, Debs versus United States.

Speaker 7 And the court upheld these convictions.

Speaker 2

Saying, First Amendment does not apply here. Like Espionage Act, lock these people up.

And Holmes, in all three of these cases,

Speaker 2 he actually writes the majority opinions.

Speaker 7 They're pretty dismissive of free speech.

Speaker 2

Like, look, we are in the middle of a war. You cannot shut your damn mouth.

Joke around. Shut your mouth.

Otherwise, you're going to prison. Absolutely.

Speaker 7 Yeah.

Speaker 7 He saw a sign that said, damn a man who ain't for his country, right or wrong. And he wrote to a friend and said, I agree with that wholeheartedly.

Speaker 2 It's like his bumper sticker.

Speaker 7 Exactly.

Speaker 2 Now, Holmes had his reasons for believing that. A lot of them going back to his experiences fighting in the Civil War.

Speaker 7 That experience, that had a huge effect on him.

Speaker 2

Like he had these kind of two complicated feelings about it. One was that it was a war to end slavery.

It was a righteous war. But at the same time, it was a brutal and barbaric fight.

Speaker 7 You know, he watched a lot of his young friends die.

Speaker 2 He almost died himself.

Speaker 7 He felt like he was an accidental survivor. He was part of the 20th Massachusetts Regiment and at Gettysburg, the vast majority of the officers in his regiment were killed.

Speaker 2 It was

Speaker 2

so devastating. For him, it was unforgettable.

Sort of forged him and made him who he was and really influenced the way he thought about the world.

Speaker 2 I mean,

Speaker 2

the war was like 50 years earlier, but he was still thinking about it. He still had his uniform hanging up in his closet and it was still stained with his blood.

And so when World War I was happening.

Speaker 7 When people were out on the battlefield risking their life, it wasn't too much to ask people at home to support that.

Speaker 2 His argument was basically that the good of the country mattered more than one person's right to say what they want.

Speaker 7 He made the analogy to vaccination. If there's an epidemic.

Speaker 2 Which for them, like us, was probably top of mind because the Spanish flu had just happened.

Speaker 7

And you think that vaccination might stop the epidemic? You force people to get vaccinated against their will. You infringe on their liberty and you force them to get vaccinated.

For the greater good.

Speaker 7 For the greater good. And he thought the same thing applied when it came to speech.

Speaker 2 Later on in his career, Oliver Wendell Holmes took this same argument to a pretty disturbing place, using it to support the practice of forced sterilization in Buck v. Bell.

Speaker 2

We actually did a whole episode about that case. But going back to speech, these three cases come to the Supreme Court.

That's in March 1919, right?

Speaker 2 Then for some reason,

Speaker 2 eight months later, in November, there's another case, the Abrams case, very similar circumstances of the case. And he switches sides.

Speaker 2 Almost all the other justices are still agreeing with the conviction, but he writes a dissent. Right.

Speaker 2 So here, so here's a quote. We should be eternally vigilant against attempts to check the expression of opinions that we loathe.

Speaker 2 And you're like, wait, that's the, you're the same guy that nine months ago was like, lock up everybody?

Speaker 2 Had he said this sort of thing ever?

Speaker 7 No, this is no, he hadn't.

Speaker 2 What happened?

Speaker 7 Right, exactly. Why did he change his mind between the Debs case in March and the Abrams case in November?

Speaker 2 Why would this nearly 80-year-old

Speaker 2 heterosexual, cisgender, white,

Speaker 2 privileged, powerful, wealthy man. Like, what made him in those eight months change his mind so radically, so quickly? Right.

Speaker 2 So really, the question is, if you boil it down into three words, the three words are, what up, homes?

Speaker 2 You're so sorry.

Speaker 2 Ridiculous.

Speaker 2 So, so in a way, it's like, it's a mystery of one man, but it's a mystery that has this ripple effect into kind of the, the, the, what is now perceived to be like the quintessential freedom in the land of the free because that dissent, that argument he made after he changed his mind.

Speaker 7 It's the reason why people like Healy say that Holmes laid the groundwork for our modern understanding of free speech.

Speaker 2 So this 180 in Holmes's head over the course of eight months, this is one of the biggest mysteries in the history of the Supreme Court. And Healy gets obsessed with this very specific question.

Speaker 2 Like, why did Holmes change his mind?

Speaker 7

Yeah, absolutely. And I I basically tried to reconstruct every day in his life for about a year and a half time period.

You're laughing, but I did. I had a spreadsheet with every day.

Speaker 2 In this spreadsheet, he only tracked each of those days in that

Speaker 2 year and a half around those eight months, right? And he microscopically pores over Holmes's life, including what Holmes was doing.

Speaker 7 And the letters he was writing, the books he was reading.

Speaker 2 He kept a log of every book that he read wow he even reads the books that holmes's friends are writing and reading just in case they had a conversation with holmes that's great and like what possibly they could have said to holmes that would have made him change his mind wow so

Speaker 11 did he find something was there like a little smoking gun or something buried in all that data

Speaker 2 Well,

Speaker 2 one thing he notices as he's digging into the daily doings of Oliver Wendell Holmes is that he became very close with a group of young progressive intellectuals in Washington, D.C.

Speaker 2 He had a group of very young friends, these brilliant progressive legal scholars.

Speaker 2 Among them was future Supreme Court Justice Felix Frankfurter, the editors of the New Republic magazine, Herbert Crowley and Walter Lippmann, this young socialist named Harold Lasky, who at the age of 24 was already teaching at Harvard.

Speaker 7 And this group, they all gathered in this house in Washington, D.C. called the House of Truth.

Speaker 2

The House of Truth. Wow.

The House of Truth. It was a townhouse.

It's like a little like clubhouse for like young progressives.

Speaker 7 And Holmes was a frequent visitor there. He would stop in on his way home from court and have a drink.

Speaker 2 And he would like play cards with them.

Speaker 7 And debate truth with them.

Speaker 2

So it's like a kind of a funny pairing. Like this nearly 80-year-old guy, like hanging out with these like young whippersnapper 20-somethings.

And like, yeah, just like laying down truth bombs

Speaker 2 holmes loved to talk to people um he loved to be challenged he loved debate and as he got older he found himself not really having anyone to do that with anymore like the sort of intellectual friends that he had who were his contemporaries those people were all dead by this point holmes was holmes was pretty old the other members of the supreme court he didn't really care for he thought that they were all sort of stodgy and he didn't think that they were that smart.

Speaker 7 Funny duddies.

Speaker 2 Yeah.

Speaker 7 And all of these young men, they worshipped Holmes.

Speaker 2 They would write him fan letters and they would write articles about him in magazines.

Speaker 7 And so he sort of found a new group of friends.

Speaker 2 They actually, they got so close that when it was Holmes's surprise 75th birthday party, his wife Fanny snuck a bunch of them in through the cellar for the for the birthday party.

Speaker 7 And he felt like some of these young men were the sons that he never had. You know, he would write letters to them and he would call them, my dear boy, my dear lads.

Speaker 2 And they'd write letters back to him saying stuff like, yours affectionately or yours always.

Speaker 7 And they would talk about how much they loved him.

Speaker 11 How did they feel about his

Speaker 2 stance

Speaker 2 on the lipolis speech stuff? Great question.

Speaker 2 They were not fans.

Speaker 7 This group essentially engaged in a kind of lobbying campaign over the course of a year, year and a half to get Holmes to change his views about free speech.

Speaker 2 So in May of that year, so remember March is when he has those first opinions.

Speaker 2 In May, they publish an article in The New Republic criticizing his opinion in the Debs case, which again was one of those earlier three cases. So they're knocking him publicly.

Speaker 7 And Holmes was so worked up by it that he sat down and he wrote a letter, kind of in a huff, to the editor of The New Republic defending himself.

Speaker 2

Essentially saying, you know, again, look, there were lives on the line. There was a war happening, a draft happening.

And he's like about to send it to the magazine.

Speaker 2 And then he like pulls back and he's like, no, no, no, I'm not going to do it.

Speaker 7 He thinks maybe it's not such a good idea to be commenting on this issue because he knows that the court has another case coming before it in the fall, the Abrams case.

Speaker 2 So in October of 1919, this case, the Abrams case, has oral arguments at the Supreme Court. Now, let me kind of hit pause on Holmes for a second and tell you about the Abrams case.

Speaker 2 So it was a Friday morning in 1918, and some random men who are on their way to work see a bunch of pamphlets on the sidewalk. They were all scattered around.

Speaker 2 Some are in English, some are in Yiddish, because it's like, it's the Lower East Side. So there would have been at that time there were like a lot of Russian Jewish émigrés like in that area.

Speaker 2

The pamphlets basically say workers wake up. The president is shameful and cowardly and hypocritical and a plutocrat.

And right now he's fighting Germany, whom we hate.

Speaker 2 but next after that he's gonna go for newly communist Russia where you guys are from and so if you don't stop working especially those of you who are working in factories who are making bullets and bombs that these weapons that these people were making were going to be used to kill their loved ones back home so

Speaker 2 quit it go on strike some detectives get on the case they find the culprits they were russian immigrants who were anarchists three men one one woman.

Speaker 7 They went on rooftops in lower Manhattan and threw these leaflets from the rooftops.

Speaker 2 They're convicted under the Espionage Act.

Speaker 2 And the case ultimately makes its way to the Supreme Court.

Speaker 7 In the fall of 1919, eight months after the earlier cases had been handed down by the court.

Speaker 2 It's a similar case to the ones before. And you'd imagine that Holmes just had that same old argument, like, you know, in his back pocket, ready to go.

Speaker 2 But

Speaker 2 Healy discovers that something happens right as the court is considering the Abrams case.

Speaker 7 Something happened to these young friends, in particular to Lasky and Frankfurter.

Speaker 2 One of Holmes's young friends, Harold Lasky, who's this socialist

Speaker 2 24-year-old teaching at Harvard, he comes out in favor of a citywide police strike. So the police

Speaker 2 in Boston are going on strike.

Speaker 7 And to the conservative alumni at Harvard,

Speaker 7 this was was just anathema. And so there was this effort at Harvard.

Speaker 2 To get Lasky fired from his job.

Speaker 7 There was a fundraising effort going on at Harvard, and a lot of the alums were saying they wouldn't give money as long as Lasky and Frankfurter were there.

Speaker 2 And he is like, if I had, if only I had a sort of a prominent Harvard alum who could stand up for me right now.

Speaker 2 And so he goes to Holmes and he's like, Holmes, they are about to fire me. He's like, please, can you write an article saying that I should be allowed to say this?

Speaker 2 And in doing so, you will save my job and my reputation, right?

Speaker 2 So Holmes is in this really tough spot because on the one hand, should he write this letter, put his neck out, but he's already as a judge said the exact opposite.

Speaker 2 And as a soldier, he believes that no, like Lasky, shut up. Or should he stay quiet and stay consistent, but then he's going to let his friend get publicly stoned, basically.

Speaker 2 So he's in this spot. And well, guess what he does?

Speaker 11

I think I know what he's going to do. He's going to write the letter.

He's going to help out Lasky.

Speaker 2 So he does not write the letter. No? He does not write the letter supporting Lasky, but instead that same week, he writes this 12-paragraph dissent to the Abrams case.

Speaker 2 The Abrams case is about a young socialist. Do you know what I mean? Like, it's like Lasky is this young radical who's getting punished for something something he said.

Speaker 2 And then at the same time, he has this case in front of him of young radicals who are getting arrested for something they said. Oh, wow.

Speaker 2 So he doesn't step in for his friend, but then he does step in for Abrams and company.

Speaker 7

So seven members of the court voted to uphold the convictions, but Holmes dissented. Here's what he wrote.

It's short. It's 12 paragraphs.

Speaker 7 So the first thing he's saying is that we should be skeptical that we know the truth.

Speaker 2 When men have realized that time has upset many fighting faiths.

Speaker 7 We've been wrong before

Speaker 7 and we're likely going to be wrong again.

Speaker 2 That the ultimate good desired is better reached by free trade and ideas.

Speaker 7 In light of that knowledge that we may be wrong, the best course of action, the safest course of action, is to go ahead and listen to the ideas on the other side.

Speaker 2 The best test of truth is the power of the thought to get itself accepted in the competition of the market.

Speaker 7 Those are the ideas that we can safely act upon. He says every year, if not every day, we have to wager our salvation upon some prophecy based on imperfect knowledge.

Speaker 2 That, at any rate, is the theory of our Constitution. It is an experiment, as all life is an experiment.

Speaker 2

Whoa, that's beautiful. Really beautiful.

Yeah. Yeah, absolutely.

Speaker 7 And

Speaker 7 the other justices on the Supreme Court, they went to his house and they tried to talk him out of it. And he said, no, it's my duty.

Speaker 2 And over the next decade or so,

Speaker 2 when other free speech cases come up.

Speaker 7 Holmes continues to write very eloquent, passionate defenses of free speech. And gradually, the other members of the court start to listen.

Speaker 2 The great legal journalist Anthony Lewis, this is the way he writes it, those dissents, and in particular the Abrams dissent, quote, did in time overturn the old crabbed view of what the First Amendment protects.

Speaker 2 It was an extraordinary change, really a legal revolution. And in particular, it's because he wrapped it in this metaphor

Speaker 2 that it caught on so quickly and widely. The idea of the marketplace of ideas exploded.

Speaker 2

The First Amendment was about the marketplace of ideas. Not just in the court.

The school is supposed to be the ultimate marketplace of ideas. But also beyond it.

The answer is more speech, not less.

Speaker 2 But as soon as you scratch the surface.

Speaker 3 That is not how the marketplace of ideas works.

Speaker 2

And start to think about how the marketplace actually works. No matter how offensive, repugnant, repellent language or image.

Like what it lets in the room.

Speaker 9 You know what we should do with Nazis? We should defeat them in the marketplace of ideas.

Speaker 2 Or how you even find it.

Speaker 7 I don't really know where that is.

Speaker 2 The metaphor that has propped up our notion of free speech for the last 100 years

Speaker 2 just starts to fall apart.

Speaker 2 And we'll get to that right after this break.

Speaker 2

Radiolab is supported by ATT. AT ⁇ T believes hearing a voice can change everything.

And if you love podcasts, you get it. The power of hearing someone speak is unmatched.

Speaker 2

It's why we save those voicemails from our loved ones. They mean something.

AT ⁇ T knows the holidays are the perfect time to do just that. Share your voice.

Speaker 2

If it's been a while since you called someone who matters, nails the time. Because it's more than just a conversation.

It's a chance to say something they'll hear forever.

Speaker 2

So spread a little love with a call this season. And happy holidays from AT ⁇ T.

Connecting changes everything.

Speaker 12 Radiolab is supported by Capital One. With no fees or minimums on checking accounts, it's no wonder the Capital One bank guy is so passionate about banking with Capital One.

Speaker 12 If he were here, he wouldn't just tell you about no fees or minimums. He'd also talk about how most Capital One cafes are open seven days a week to assist with your banking needs.

Speaker 12

Yep, even on weekends. It's pretty much all he talks about in a good way.

What's in your wallet? Terms apply. See capital one.com/slash bank, capital One, NA, member FDIC.

Speaker 13

Radio Lab is supported by Ripling. Finance teams often spend weeks chasing receipts, reconciling spreadsheets, and fixing errors across disconnected spend tools.

This can be frustrating.

Speaker 13 And that's not software as a service. That's sad.

Speaker 13 Software as a disservice. If you've been thinking about replacing stitched together tech stacks with one platform for all departments, Rippling can help.

Speaker 13 Rippling is a unified platform for global HR, payroll, IT, and finance, helping people replace their mess of cobbled-together tools with one system designed to help give leaders clarity, speed, and control.

Speaker 13 By uniting employees, teams, and departments in one system, Rippling works to remove the bottlenecks, busy work, and silos in business software.

Speaker 13 With Rippling, you can choose to run HR, IT, and finance operations as one, or pick and choose the products that best fill the gaps.

Speaker 13

Right now, you can get six months free when you go to Rippling.com slash Radiolab. Learn more at R-I-P-P-L-I-N-G.com/slash slash radiolab.

Terms and conditions apply.

Speaker 12

Hi, I'm Lulu Miller, and this episode is sponsored by BetterHelp. The holidays are a time of old traditions, lighting candles in the window, singing centuries-old songs.

But why stay wed to the past?

Speaker 12 I've heard all kinds of stories lately of people inventing new traditions, like my friends Lena and Jamie, who celebrated what they called trash giving last year by picking up trash trash in the morning and then eating trashy food together at night.

Speaker 12 Or my friend Terry, who skipped out on Thanksgiving altogether last year for a solo camping retreat of replenishment. Holidays can bring up the feels, good feels and hard feels.

Speaker 12 It's natural and a great way to navigate all of them is through the regular practice of therapy. Why not try something new and different? like giving yourself the gift of therapy.

Speaker 12 And one of the easiest ways to get you going on this journey is BetterHelp. BetterHelp does the initial matching for you so you can focus on your therapy goals.

Speaker 12 A short questionnaire helps identify your needs and preferences, and their 12-plus years of experience means they typically get it right the first time.

Speaker 12 And if you aren't happy with your match, you can switch to a different therapist at any time from a list of recommendations tailored to your needs. This December, start a new tradition.

Speaker 12

Treat yourself by taking care of you. Our listeners get 10% off at betterhelp.com/slash radio lab.

That's betterhelp.com/slash radio lab.

Speaker 7 Jad.

Speaker 11 Lothiff. Radio Lab.

Speaker 2 And we're back

Speaker 2 freely talking about talking freely and Oliver Wendell Holmes and the marketplace of ideas.

Speaker 11 And just what a powerful metaphor that has become for us.

Speaker 2 Right. And in a way, I do think that there's something so beautiful about the fact that this came out in a dissenting opinion that his fellow Supreme Court justices tried to quash.

Speaker 2 That's in a way, it's its own argument. It's like the most persuasive evidence of all for the marketplace of ideas is that if Holmes hadn't himself dissented,

Speaker 2 we wouldn't have the free speech we have today.

Speaker 11

I love that, what you just said. I think that's beautiful.

The way in which his argument won is itself proof of the very thing he's saying. Right.

Speaker 11 But the problem with the marketplace of ideas is that it expresses an ideal that is so much more powerful and beautiful than the reality.

Speaker 2 Well, so

Speaker 2 what's interesting is that Holmes' argument, argument, it's a functional argument. It's in the barter, right, in the marketplace that the truth will rise to the top.

Speaker 2

This will function as a way to sift out the good ideas and the truth. So it's actually a measurable thing.

Like we have marketplaces of ideas. Like Twitter is a marketplace of ideas, right?

Speaker 2 Where things get, you know,

Speaker 2 shouted down and shamed and shouted down and shamed or spread and celebrated. And the the amazing thing about Twitter is that you can see that happen.

Speaker 2 There's real data there about retweets and likes and whatever else that you could actually use it to test Holmes's idea. Like, does the truth, do the good ideas, actually rise to the top?

Speaker 9 That's exactly right. I mean, as we started to see fake news on Twitter and on Facebook, we realized we had the data to study this kind of question.

Speaker 2 So I talked to this data and marketing researcher, Sinan Aral, professor, MIT. A couple of years ago, he and some of his colleagues at MIT, they took a quantitative look at this exact question.

Speaker 2 Like, how do truths and falsehoods fare in the marketplace of Twitter?

Speaker 9 Every verified story that ever spread on Twitter since its inception in 2006, we captured it.

Speaker 2 They started by gathering up stories from a couple of fact-checking websites: Snopes, PolitiFact, Truth or Fiction, Factcheck.org, Urban Legends, and so on and so forth.

Speaker 2 And they just listed all the stories that those sites had fact-checked, like about anything. Politics, business, all kinds of stuff.

Speaker 9 Science, entertainment, natural disasters, terrorism, and war.

Speaker 2 And of all the stories they looked at, some were true and some were false.

Speaker 9 Then we went to Twitter.

Speaker 2 And they found for each story the first tweet, basically its entry into the marketplace.

Speaker 9 And then we recreated the retweet cascades of these stories from the origin tweet to all of the retweets that ever happened.

Speaker 2 And so for each story they ended up with a diagram that showed how it spread through the Twitterverse.

Speaker 2 And when you look at these diagrams...

Speaker 9 They look like trees spreading out.

Speaker 2 And the height and width of each tree would tell you how far and wide the information spread.

Speaker 9 Some of them are long and stringy, with just one person retweeting at a time. Some of them fan out.

Speaker 2 Tons of people retweeting the original tweet, then tons more people retweeting those retweets.

Speaker 9 Lots of branches.

Speaker 2 On top of that, they could see just how fast the tree grew.

Speaker 9 How many minutes does it take the truth or falsity to get to 100 users or 1,000 users or 10,000 users or 100,000 users?

Speaker 2 And Sinan says that when they analyzed and compared the breadth and the depth and the speed of growth of all those different tree diagrams,

Speaker 9 what he got was the scariest result that I've ever uncovered since I've been a scientist.

Speaker 2 The trees of lies spread further, wider, and faster than the truth trees.

Speaker 9 It took the truth approximately six times as long as falsity to reach 1,500 people.

Speaker 9 So falsehood was just blitzing through the Twitter sphere. You know, we're in a state now

Speaker 9 where the truth is just getting trounced by falsehood at every turn.

Speaker 2 So in this marketplace of ideas, the truth does not rise to the top.

Speaker 11 Well, that does not surprise me, not even a little bit.

Speaker 2 That's part of what we reported back in 2021.

Speaker 2 And listening back now, the way we were talking about it then feels almost quaint.

Speaker 2 Now that the platforms themselves have become more political with the rise of better and easier to make deep fakes, and we just had the release of Sora 2, it's like we're in this whole new, more complicated phase of misinformation online.

Speaker 2 But I do think, even given all of that, this next conversation that I'm about to play for you from the same episode, totally holds up. It reframes the conversation about

Speaker 2 and free speech, which I think is half the battle to finding a way out of this mess. Hello.

Speaker 2

This is my friend Nabiha Syed. How are you? Good.

Did this work? And I called her because she knows more about the First Amendment than anyone else I know.

Speaker 2 She's an award-winning media lawyer and just someone who is really earnestly trying to imagine the best way forward.

Speaker 14 And I'm the president of the markup, a nonprofit news organization that investigates big big tech.

Speaker 2 And one of the first things she told me was that one of the problems with the marketplace of ideas is that there's

Speaker 14 no

Speaker 14 reckoning for the fact that some people have bigger platforms than others, meaning their ideas get heard first. Their ideas also get heard more often.

Speaker 14 Their ideas are also, you know, surrounded by joiners who are like, that idea is popular. I'm going to join it.

Speaker 2 And part of it, she was saying, like, look, like, as a Muslim woman, um, who grew up like right after 9-11.

Speaker 14 You know, not that all things in the American Muslim experience boil down to a single date in 2001, but to the extent that like the aftermath of 9-11 was formative, it was because I felt like there was all of a sudden a narrative about who I was that was playing out in the media.

Speaker 2 You know, like as we all know, it's like Muslim terrorists blah, blah, blah, blah.

Speaker 14 That bore no relationship to my Orange County, Pakistani, like Kardashian-esque life, right?

Speaker 2

Like I just didn't, I was like, who are these people? Who this? And she's like, and I never, my people never got the mic. It's about power.

It's about megaphones.

Speaker 14 But here's the thing to remember: like the marketplace of ideas was one theory, right?

Speaker 14 It's the, it's the idea that we glommed onto, and it's the idea that really took off because a variety of social platforms were like, yep, that's the one.

Speaker 2 Because it was this sort of idealistic metaphor, but also because it was the most convenient, laissez-faire, set it and forget it sort of model for free speech.

Speaker 14 But it's not the only one.

Speaker 2 Historically, there have been a bunch of other models and metaphors that people have used to talk about free speech.

Speaker 2 Some of which take the view not so much that, you know, argument and dissent lead to truth, but instead

Speaker 2 that like there's a truth out there in the world and that people have a right to hear it.

Speaker 14 You should know, is the well in your neighborhood poisoning you? Yes or no?

Speaker 2 Like, what are the facts that you need to know to live your life and operate in society?

Speaker 14

That's not a a subjective set of opinions. Like, is water poisonous? Yes.

Why?

Speaker 2 And what was interesting to me about this view is, is unlike Holmes' argument, and for that matter, unlike the, you know, attitude of this is America, I can say whatever I want, this view.

Speaker 14 Conceives of like the rights of a listener, not just the rights of a speaker.

Speaker 2 The way that we do things now.

Speaker 14 We focus a lot on who gets to talk. right and everyone's talking somehow blah blah magic happens

Speaker 14 we don't ever talk about the listener Like if you're listening to all these people talking, do you have a right to accurate information? And you see some glimmers of that throughout American history.

Speaker 2 So for example, in 1949, the government actually set a policy, basically a rule saying if you are a news broadcaster, you know, you have to present both sides of an issue.

Speaker 14 You have to provide facts on these different sides of issues.

Speaker 2 And so Nabiha's feeling about all of this is like, if we're going to rethink the marketplace as it exists now, maybe we should incorporate some of this other kind of thinking.

Speaker 14 We should start from the vantage point of the facts and information you need to participate in democratic deliberation, which could be local, which could be national, but we're going to focus on information health, not just the right of someone to speak.

Speaker 11 Although it's interesting, like

Speaker 11 it doesn't negate the metaphor.

Speaker 2 Uh-huh.

Speaker 11 The problem is the metaphor is so beautiful,

Speaker 11 it distracts you from those key questions.

Speaker 2 It totally does.

Speaker 11 But those questions can be used to repair the the metaphor into something that's actually functional.

Speaker 2 Can't you just say the marketplace of ideas, asterisk?

Speaker 11 Okay. And then in the asterisk, it's like

Speaker 11 assuming that everyone has equal access to the marketplace, assuming that each voice is properly weighted, assuming that truth and falsehood are somehow taken into account,

Speaker 2 that

Speaker 11 I mean, what we're talking about is a regulated market of ideas.

Speaker 2 Yeah, I mean, I think that's good. But then the question is: like, who regulates it? How do we regulate it?

Speaker 2 Right now, the people who's regulating it, like, we have the courts with like Citizens United being like, we don't. Unfortunately, yeah.

Speaker 2 And now it's going to be Facebook and the CEO of Twitter is the one regulating.

Speaker 2 It doesn't make sense, like, who has that power and how do we negotiate over that power, which sort of just feels like we're back at square one, right?

Speaker 2 Like, like, we're back to the original problem, like, who should regulate speech? And then, and then, so I went back to Healy

Speaker 2

just to put all this in front of him to see if he had any thoughts. Yeah, I actually do.

And the first thing he said was, okay, yes, the marketplace idea, the way it works now, it's broken. And

Speaker 2 in general, it's just an odd way to think about speech.

Speaker 7 This kind of weird, you know, commercial understanding of free speech. What about thinking about us all as scientists?

Speaker 2 Because you're not buying and selling potatoes. You're looking for truth.

Speaker 7

Absolutely. Right.

We're not buying and selling potatoes. We're testing the theory of relativity.

Speaker 2 Yeah.

Speaker 2 But he pointed out to me something something else that Oliver Wendell Holmes said in that Abrams Descent.

Speaker 7 It turns out that Holmes relied on another metaphor in his Abrams descent as well.

Speaker 2 There's a thing he says right after the marketplace idea.

Speaker 7 He writes, that at any rate is the theory of our constitution. It is an experiment, as all life is an experiment.

Speaker 2 And so Healy says what he thinks about is that one word, experiment.

Speaker 7 And what Holmes could have possibly meant by that.

Speaker 2 And he's come to the view that Oliver Wendell Holmes was probably acutely aware through all of his experiences that reckoning with free speech when you're trying to build a democracy.

Speaker 7 It doesn't end.

Speaker 2 We don't win the game.

Speaker 7 The whole point of free speech is not that, oh, we've got free speech. Now democracy is easy.

Speaker 2 No, democracy is hard. And so to Holmes, the point wasn't to get to some definitive moment of triumph.

Speaker 2 It was just to keep the experiment itself going for as long as possible.

Speaker 7 And one of the ways to promote the success of an experiment is to build in some flexibility.

Speaker 2 When the experiment doesn't go the way that you expect, when your initial ideas are challenged, you adapt. You come up with new ideas.

Speaker 7 Even new metaphors. And so that's another way to think about free speech.

Speaker 2 That we constantly have to be rethinking what we even mean by free speech. Okay.

Speaker 2 It's a constantly tweaking thing. Like it's a thing that we, it's, it's never set, but it's something we need to kind of keep tweaking as we're going and keep refining.

Speaker 14 The marketplace of ideas has been such a beautiful idea and it served us for about a century. And maybe it's time to think about what a different theory could look like.

Speaker 2 So what's the better theory? I mean, now is the time for you to kind of lay down this bombshell of this new theory. What is it? Oh, cool.

Speaker 14 Yeah. No, I don't have it yet, but

Speaker 2 I'm working on it.

Speaker 2 Speaking of which, what is a better metaphor? What is a better way to think about free speech in a modern society?

Speaker 11 Email us at radiolab at wnyc.org.

Speaker 2 Yeah. Email us, tweet at us.

Speaker 2 Maybe don't tweet at us given what we've learned, but let us know what you think.

Speaker 2 If you want to keep tabs on the wonderful Nabiha Syed,

Speaker 2 you can find her at themarkup.org.

Speaker 2

Obviously, this whole episode started with Thomas Healy's book, The Great Descent. And he actually has a new book out called Soul City.

This episode was produced by Sara Kari.

Speaker 2

Thanks to Jenny Lawton, Soren Shade, and Kelsey Padgett, who actually did the initial interview with Thomas Healy with me back in the more perfect days. I'm Jad Ab Umraad.

I'm Latif Nasser.

Speaker 11 Thanks for listening.

Speaker 3

My name is Rebecca, and I'm from Brooklyn. And here are the staff credits.

Radio Lab is hosted by Lulu Miller and Latif Nesser. Soren Willer is our executive editor.

Speaker 3

Sarah Sandbach is our executive director. Our managing editor is Pat Walters.

Dylan Keefe is our director of sound design. Our staff includes Simon Adler, Jeremy Bloom, W.

Speaker 3 Harry Fortuna, David Gable, Maria Paz Gutierrez, Sindhu Nyanan Sabanan, Matt Kilty, Mona Magavgar, Annie McEwen, Alex Neeson, Sara Kari, Anissa Vice, Arianne Wack, Molly Webster, and Jessica Jung, with help from Rebecca Rand.

Speaker 3 Our fact-checkers are Diane Kelly, Emily Krieger, Anna Bahol Mazzini, and Natalie Middleton.

Speaker 15 Hi, I'm Victor from Springfield, Missouri. Leadership support for Radiolab Science Programming is provided by the Simons Foundation and the John Templeton Templeton Foundation.

Speaker 15 Foundational support for Radio Lab was provided by the Alfred P. Stone Foundation.

Speaker 12 Hear that?

Speaker 16 That's me with a lemonade in a rocker on my front porch.

Speaker 12 How did I get here?

Speaker 16

I invested to make my dream home home. Get where you're going with MDY, the original mid-cap ETF from State Street Investment Management.

Getting there starts here.

Speaker 8

Before investing, consider the fund's investment objectives, risks, charges, and expenses. Visit state street.com/slash IM for prospectus containing this and other information.

Read it carefully.

Speaker 8

MDY is subject to risks similar to those of stocks. All ETFs are subject to risk, including possible loss of principal.

ALPS Distributors, Inc. Distributor.

Speaker 1 NYC Now delivers breaking news, top headlines, and in-depth coverage from WNYC and Gothamist every morning, midday, and evening.

Speaker 1 By sponsoring our programming, you'll reach a community of passionate listeners in an uncluttered audio experience. Visit sponsorship.wnyc.org to learn more.