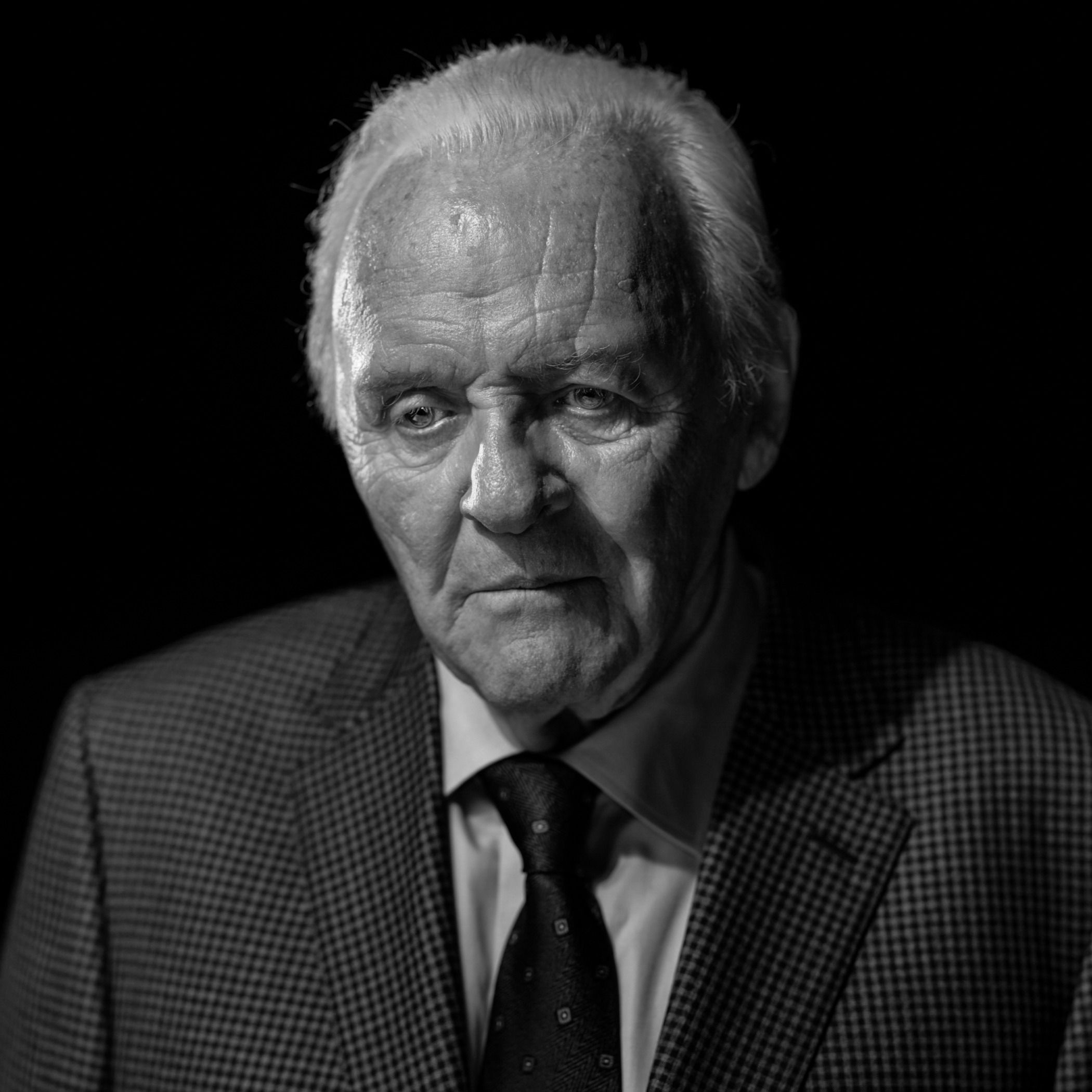

'The Interview': Anthony Hopkins on Quitting Drinking and Finding God

The legendary actor, 87, is looking back with tears in his eyes.

Press play and read along

Transcript

Transcript is processing—check back soon.

The Daily — 'The Interview': Anthony Hopkins on Quitting Drinking and Finding God