869: Harold

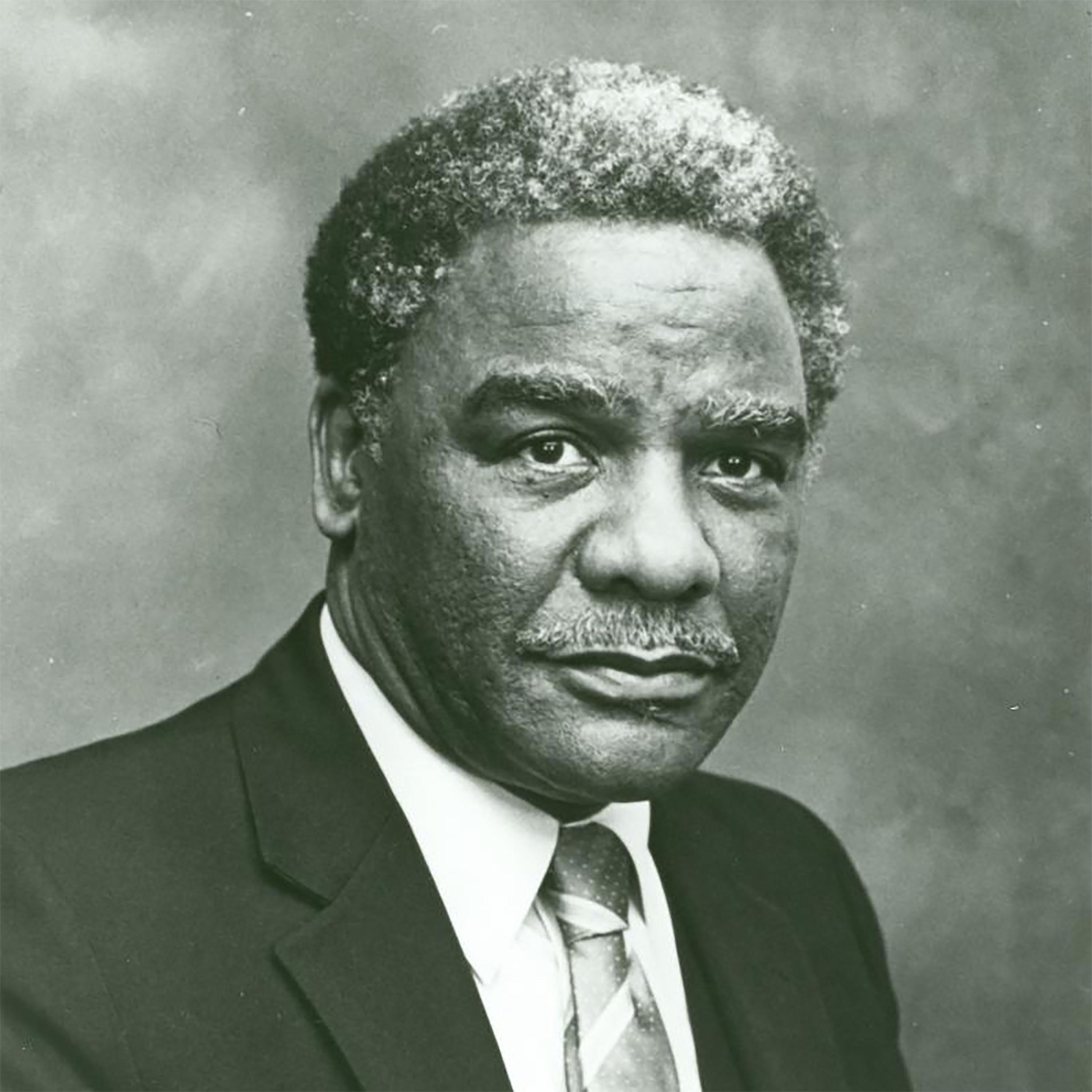

When Zohran Mamdani won the primary race for New York mayor, the Democratic establishment's lukewarm response echoed the treatment of another charismatic, unconventional candidate decades earlier. This week, we bring you the story of Harold Washington, the greatest politician you've probably never heard of, and the backlash that ensued when he became Chicago's first Black mayor.

Visit thisamericanlife.org/lifepartners to sign up for our premium subscription.

- Prologue: As New York City’s Democratic establishment attempts to resist the candidacy of Zohran Mamdani, we look back at another mayoral candidate who upset the established political machine. (7 minutes)

- Act One: A history of the brief mayoral career of Harold Washington and its lessons for Black and white America, as told by people close to him. (39 minutes)

- Act Two: Ira revisits interviews with Chicago voters from the 1997 and 2007 rebroadcasts of this episode. In 1997, ten years after Harold Washington’s death, not much had changed in Chicago. By 2007, attitudes had begun to shift slowly, and another Black politician from Chicago was on the rise — Barack Obama. Ira also speaks to David Axelrod, an advisor to both Harold Washington and Barack Obama. (10 minutes)

Transcripts are available at thisamericanlife.org

This American Life privacy policy.

Learn more about sponsor message choices.

Press play and read along

Transcript

Speaker 1 Support for this American life comes from ATT. You know that feeling when someone's already looking out for you before you even need it?

Speaker 1

ATT brings that kind of reliability to your connection with the ATT guarantee. Staying connected matters.

That's why ATT has connectivity you can depend on, or they'll proactively make it right.

Speaker 1

That's the ATT guarantee. Terms and conditions apply.

Visit ATT.com/slash guarantee for details.

Speaker 2 One thing that's been interesting watching the rise of the New York mayoral candidate, Zoron Mamadani, who's a Democrat, is watching precisely how much of the Democratic machine has come out to support him.

Speaker 2 After he won the Democratic primary, of course, normally the party would fall in behind him. And in fact, some prominent Democrats have come forward and endorsed him.

Speaker 2

But not all of them. Not some of the most important New York Democrats.

Senate Minority Leader Chuck Schumer. House Minority Leader Hakeem Jeffries.

Former New York Mayor Michael Bloomberg.

Speaker 2 And I'm bringing all this up today because watching this, it reminded me of the story of another charismatic politician ages ago, Harold Washington, the first black mayor of Chicago.

Speaker 2 Harold became mayor back in 1983, and that was so revolutionary at the time that a black man would become mayor of the city of Chicago that after the primary, the Democratic Party turned on him.

Speaker 2 And an old school Democrat, a white guy, ran as an independent against Harold in the general election,

Speaker 2 much like Andrew Cuomo has done with Mamdani.

Speaker 2 Back then, most in the Democratic machine endorsed the white guy in the general election.

Speaker 2 And then, once Harold took office, Democrats continued to fight him and the changes that he wanted to make.

Speaker 2

I want to be clear, like, I don't want to oversimplify in comparing these two stories. So much of Harold's story is very different than Zoran Mamdani's.

The opposition to Harold was over race.

Speaker 2 The opposition to Mamdani is more about his views on Israel and his socialism or progressivism or whatever you want to call it.

Speaker 2 The race in religion, the fact that he's Muslim, is definitely in there too.

Speaker 2 But Harold's story is a parable about a Democrat whose very existence made the party have to question what it was all about,

Speaker 2 which seems very much like Mamdani.

Speaker 2 So we're going to replay his story today.

Speaker 2 Back in 1997, 10 years after Harold died, we did a full episode about him. And can I say, if you don't know anything about Harold Washington, you're in for a treat.

Speaker 2 He is this charismatic, idealistic man, very funny, very smart, great talker, a Democrat framing issues with a skill that it is really hard to think of any Democrat in office right now who does it as well.

Speaker 2 But also, a pragmatist, somebody who got elected, somebody who got things done.

Speaker 2 So I hope you like this. It's one of my favorite episodes we've ever done.

Speaker 2 Here we go. Here's that show from 1997.

Speaker 2

Before our story begins, let's remember how it used to be. Jackie lived on the south side in a black neighborhood.

City didn't enforce the housing code properly, didn't investigate arsons.

Speaker 8 There would be fires going on in Woolworth daily, several times a day, and it was just fire engines all the time. And so,

Speaker 8 my daughter started to believe that when buildings got old

Speaker 8 and died, like people got old and died, that you knew a building was old and was dying because it would burn up.

Speaker 2 Before our story begins, Chicago was run by the Democratic machine and black alderman of Danny Davis. We turned out to vote for the machine election after election.

Speaker 2 But the machine didn't reward the black wards for those votes the way it paid back the white wards on the north side, with street cleanings and sewers with newly paved roads and sidewalks economic development money well actually uh you know they we we we had called the areas um colonies as i mean i mean and and and

Speaker 4 just basically picking up the garbage in these wards just trying to keep them clean was a real problem

Speaker 4 Person who was elected, you know, there would be so much focus on garbage pickup that, you know, you'd almost have to just be the garbage alderman.

Speaker 4 I mean I recall telling people time and time again that I was tired of just being the garbage alderman.

Speaker 2 Before our story begins, the Chicago political machine squeezed black kids into mobile trailers behind public schools rather than let them attend white schools just blocks away.

Speaker 2 Before our story begins, the Chicago machine built high-rise public housing to hold blacks on the south side and keep them from moving into white neighborhoods.

Speaker 2 Before our story begins, the Chicago political machine built a system of highways that coincidentally divided black neighborhoods from white and particularly insulated the mayor's all-white neighborhood, Bridgeport.

Speaker 2 Typical inequities? Unemployment in the white 11th ward was 0%.

Speaker 2 Unemployment in the 4th ward, where blacks lived, was 25%.

Speaker 2 This is a story about one ethnic group doing what so many other ethnic groups have done in this country. Put its own candidate in City Hall, won the mayor's office.

Speaker 2 But because this ethnic group happened to be black, what happened was unlike anything that happens when an Italian politician or an Irish politician or Jewish politician takes City Hall.

Speaker 2 White voters deserted their own political party. White politicians tried to stage a public, slow-motion coup.

Speaker 2 And the mayor faced pressures that were different from those faced by any white mayor of any city in America. And nobody tried to pretend that the fight was not about race.

Speaker 10 Good evening, you're on with Harold Washington.

Speaker 12

Good evening, Mr. Washington.

Could you clear up a point for me?

Speaker 12 I understand that once you move into City Hall, you're going to remove all the elevator boxes and replace them with vines.

Speaker 12 Is that true?

Speaker 12 What? Replace them with what? With vines.

Speaker 12 Vines? Yeah, yes.

Speaker 13 You know what?

Speaker 9 I'm not even going to ask you why.

Speaker 9 No, I don't think we have three million TARS in this city.

Speaker 13 Randall is gone.

Speaker 2

Welcome to WBEZ Chicago. It's This American Life.

I'm Aaron Glass. Today we bring you the story of Harold Washington, Chicago's first black mayor.

Speaker 2

He died early in his second term of office, back in 1987. Act one of our program today is about what happened during Harold's life.

Then we we have a short act two about what came afterwards.

Speaker 2 A word about the voices you're going to be hearing over the course of this hour. It's mostly people who are close to Harold Washington.

Speaker 2 Many of them activists and politicians, Lou Palmer, Judge Eugene Pincham, Congressman Danny Davis, then Alderman Eugene Sawyer.

Speaker 2 There are people from his administration, Jackie Grimshaw, Grayson Mitchell, Tim Yule Black, and some reporters who followed his story, Vernon Jarrett, Monroe Anderson, Gary Rivlin, Laura Washington, who later became his press secretary.

Speaker 2 There will also be an occasional opponent or voter. Stay with us.

Speaker 2 Support for this American Life comes from Squarespace. Their AI-enhanced website builder, Blueprint AI, can create a fully custom website in just a few steps.

Speaker 2 Using basic information about your industry, goals, and personality to generate content and personalized design recommendations. And get paid on time with branded invoices and online payments.

Speaker 2 Plus, streamline your workflow with built-in appointment scheduling and email marketing tools. Head to squarespace.com/slash American for 10% off your first purchase of a website or domain.

Speaker 1

This message comes from Apple Card. Each Apple product, like the iPhone, is thoughtfully developed by skilled designers.

The Titanium Apple Card is no different.

Speaker 1 It's laser-etched, has no numbers, and rewards you with daily cash on everything you buy, including 3% back at Apple. Apply for Apple Card in minutes.

Speaker 1 Subject to credit approval, AppleCard is issued by Goldman Sachs Bank, USA, Salt Lake City Branch.

Speaker 3 Terms and more at applecard.com.

Speaker 2 Do you have a question that no one in your life can help with?

Speaker 7 Something that makes the people around you go, yikes, what a weird question.

Speaker 2 Well, freak, here on How to Do Everything, we want to help you out. Each week, we get fantastic experts to answer your questions.

Speaker 7 People like U.S. Poet Laureate Ada Limon, bodybuilder Arnold Schwarzenegger, and rapper Rick Ross.

Speaker 2 Season two two just launched to go listen to How to Do Everything from NPR.

Speaker 2 Yesterday.

Speaker 2 For decades, Chicago politics had been run with an iron hand by the legendary political boss Richard J. Daley.

Speaker 2 Our story begins just after his death in 1976, when the machine was sputtering a bit with no strong leader and the possibility, a small possibility, of change.

Speaker 2 To give you a sense of what it meant to be a loyal black alderman in the Chicago machine at at that time, consider what happened in City Hall the day Richard Daly died.

Speaker 15 By tradition,

Speaker 6 the president pro tem of the city council should have at least occupied the mayor's office until such time as a process was determined for the election of a new mayor.

Speaker 3 And who was the

Speaker 14 black alderman? A loyal black alderman from the 34th ward, a daly Democrat, a lawyer,

Speaker 6 impeccable reputation, impeccable credentials.

Speaker 14 The only

Speaker 16 misqualification he had was he's black. God ordained that he'd be born black.

Speaker 6 And the power structure sent police officers to the fifth floor, armed to sit at the door to prevent Frost from even entering the mayor's office.

Speaker 15 That was a tremendous insult.

Speaker 2

It was an insult, but it was not unusual. The white machine picked who the black leaders would be.

And And mostly, those leaders did what they were told.

Speaker 2

Blacks in Chicago had nowhere to go but the Democratic machine. They were stuck.

But then, there were a series of famous and especially infuriating insults from the white political establishment.

Speaker 2 Biggest among them, black voters finally elected an anti-machine candidate named Jane Byrne, who, once in office, betrayed them.

Speaker 2 sucked up to the white machine, made appointments and decisions specifically to prove she was not in the pocket of black Chicago.

Speaker 2 Then, circumstances came together, some by planning, some by luck, that made it possible to elect a black mayor. The planning.

Speaker 2 Organizers registered over 100,000 minority voters, held rallies and meetings declaring it was time to elect a black mayor.

Speaker 3 The luck.

Speaker 2

Two white candidates split the white vote. One more piece of luck.

The Chicago Democratic Party had created, in spite of itself, Harold Washington.

Speaker 2 Vernon Jarrett was an old friend and a local newspaper columnist.

Speaker 17 And Harold was in that party now.

Speaker 21 Don't forget, Harold had been a precinct captain.

Speaker 22 His father had groomed him as a precinct captain since he was, what, 11 years old. But his father was doing wrong.

Speaker 21 So Harold

Speaker 22 is an unusual person in that he nursed this resentment of how the Democratic Party had deserted his father at one time, and his father ran for alderman of the third ward.

Speaker 22 He's a confused guy, got a little sense of mission in him, and wanting to do the right thing, but yet he was balanced off by this pragmatism that you got to play ball to a degree with the organization.

Speaker 22 And he was correct.

Speaker 22 He wouldn't have made it without the Democratic machine.

Speaker 2 Usually in Chicago, political activists had a choice. They could go with politicians who were good on the issues but then had no political experience dealing with the machine.

Speaker 2 Or they could get hacks who knew the machine but were terrible in the issues. Washington was the rarest kind of politician, delivered on the issues, knew the machine.

Speaker 2 Which is why, in fact, he did not want the job. Lou Palmer was at the center of the effort to draft a black mayor.

Speaker 9 Well, we talked to Harold.

Speaker 13 He was reluctant, very reluctant.

Speaker 9 At the time, he was in Congress and was enjoying being a Congressman.

Speaker 2 Enjoying it partly because he was far from the machine.

Speaker 9 He set some requirements or how much money we'd have to raise, we'd have to

Speaker 23 get 50,000 new voters.

Speaker 9 Do you ask that thinking, well, you'll never get that. He used 50,000 knowing that nowhere in the world are they going to come up with 50,000 new registered.

Speaker 9 That was hard in those days to come up with 50,000 registered voters.

Speaker 2 They registered 130,000 new voters.

Speaker 21 May I jump ahead a moment? You know what put Harold Washington over

Speaker 22 with the broad masses of black people was when they had the primary debates.

Speaker 22 Oh,

Speaker 8 the triumph was a televised debate.

Speaker 9 You know, because you had Daly, you had Byrne, and then you had somebody who could talk, Harold.

Speaker 2

Let's review that lineup. Daly was Richard M.

Daley, son of the late Mayor Richard J. Daly.

Speaker 2 Byrne was Jane Byrne, the then incumbent mayor. And Harold, you already know Harold.

Speaker 2

Those were the three Democratic contenders in the mayoral race. It is the fall of 1983.

Here's a typical exchange between them.

Speaker 2 Three of them were asked at one point what they would do, if anything, about the police department's Office of Professional Standards, the place in the police department which handles complaints about police misconduct and brutality.

Speaker 2 Jane Byrne and Richard Daly

Speaker 2 sound basically like normal politicians. They offer dull truisms like.

Speaker 25 I believe that the members of the police board, chaired by Reverend Wilbur Daniels, really do take that job very seriously.

Speaker 2 Here's the most specific that Richard Daly, then state's attorney, got that day.

Speaker 26 I think like anything else, there must be improvement, and there is nothing wrong with improvement in the Office of Professional Standards.

Speaker 2 When Harold Washington comes on, what is most noticeable is that he sounds like a human being.

Speaker 11 The precise question is what would I do to improve the Office of Professional Standards? When I answer it, I'll be the only one who answered the question.

Speaker 11 The Office of Professional Standards was arrived at after a long and torturous situation in this city in which members, not all, but members of the Chicago Police Department consistently refused to be adequate and professional in their handling of Hispanic black people.

Speaker 11 It's just that simple.

Speaker 24 What happened was he became plausible to the black community.

Speaker 24 Suddenly, they heard somebody who was articulate

Speaker 24 knew what he was talking about

Speaker 15 and was forceful.

Speaker 11 In the first place, the appointees, all but nine, are political appointees. Many of the investigators are wedded to or related to police members of the Chicago Police Department.

Speaker 22 A lot of people, black people, had felt all along

Speaker 22

that we've been bossed by Dunderheads. They are not that bright.

They don't know that much. And

Speaker 22 Harold Washington standing there between Jane Bryan and Richard M. Daley, the son.

Speaker 3 So cool, so well read,

Speaker 22 that people, black people, just thrilled. It was like watching Michael Jordan with a basketball.

Speaker 11 Mr.

Speaker 10 Brezak, unfortunately, at the behest of this mayor, as a minion of this mayor, as a subaltern of this mayor, as a subordinate of this mayor, has restored his credibility.

Speaker 28 How used to use words that even some of these journalists, these white journalists, had to scratch their head and go to the dictionary.

Speaker 13 But black people love that.

Speaker 19

And he jumped on Jane Byrne and took her by surprise, shocked her, and she was still reeling from the shock. And I shall never forget it that night.

This man got it made.

Speaker 17 He's in.

Speaker 2 Here's one way that being a black candidate for office is different from being a white candidate.

Speaker 2 If you're black, you get thrown into the chasm of misunderstanding that divides white America from black America in a way that white politicians almost never are.

Speaker 2

Two Americas simply see certain things differently. For instance, what should Harold Washington say about the late Mayor Richard J.

Daley?

Speaker 2 Many white Chicagoans still held him in awe, while black and Latino Chicago, for good reasons, had a different take.

Speaker 2 Daly openly stood against integration of the city's neighborhoods. The night after Martin Luther King Jr.'s death, he ordered police to shoot to kill rioters.

Speaker 2 Well, here's what Harold decided to say.

Speaker 30 When he says that he would hope that I would have all the good qualities of past mayors, there are no good qualities of past mayors to be had. None, none, none,

Speaker 30 none.

Speaker 30

I did not mourn at the bar of the late late mayor. I regret anyone dying.

I have no regrets about him leaving. He was a racist from the core, head to toe and hip to hip.

Speaker 30 There's no danger of doubt about it.

Speaker 30 And he spewed and fought and oppressed black people to the point that some of them thought that was the way they were supposed to live.

Speaker 30 Just like some slaves on the plantation thought that was the way they're supposed to live.

Speaker 31 It was just like everything else he did and said it was historic.

Speaker 31 No one would challenge the late mayor on anything, much less call him that kind of name. And I think that was what made him so provocative.

Speaker 31 It's what made him so loved by the people who supported him and so hated by the people who wanted to deny him the office. He didn't miss any words.

Speaker 30 I give no husanas to a racist, nor do I appreciate or respect his son. If his name were anything up than Daly, his campaign would be a joke.

Speaker 30 He has nothing to offer anybody but a bent-up tin can smile,

Speaker 30 no background,

Speaker 30

and he runs on the legacy of his name, an insult to common sense and decency. Everything I've ever got in the world, I worked for it.

Nobody gave me anything.

Speaker 20 The primary taught him that He could transcend being the third candidate, being the black candidate. And he could take that Adam Powell positioning.

Speaker 20 He could take that Marcus Garvey positioning, where you're the hybrid between the politician and the public man. And you become somewhere between Muhammad Ali, Michael Jackson, somewhere in superstar.

Speaker 30

And although I may sound abrasive, I have no malice toward anybody. I have a job to do.

I've got places to go and things to do.

Speaker 30

And I approach this job just like any masterful surgeon when you have to cut out a cancer. I cut it out with no emotion.

Get it out. Get it out.

Speaker 30 This dominant culture may have messed up my pocket, but they haven't messed up my head one bit.

Speaker 30 I believe in the powers of redemption and I simply cannot believe in the God I worship that he would permit us to sit on this earth for 400 years or rather in this country for 400 years and suffer the indignities which we have suffered, piled time after time, high after high, and so heavy it has almost broken the backs backs of one of the most powerful people in this world.

Speaker 30

I can't believe there is no redemption. But that redemption is not going to come out in hatred.

It's going to come out in positive attitude toward our fellow man.

Speaker 30 We've come into the 1980s with an understanding that we have not just a right but a responsibility to give the best that we have to a society.

Speaker 30 We want to give it, and we're going to give it if we have to beat them across here and knock them down and make them take it. We're going to give it to them.

Speaker 2 During this election and during Harold Washington's terms as mayor, in Chicago, every day was the day after the OJ verdict.

Speaker 2 Every day was the day when black and white Chicago took a look at the same set of facts and drew two different conclusions.

Speaker 2 For instance, when the media raised questions about Washington's past, it made white Chicagoans question his qualifications for office, but it made minority voters more loyal.

Speaker 15 In 1983, when Harold announced his candidacy,

Speaker 17 95% of black people never heard of him.

Speaker 3 And what happened was

Speaker 3 the

Speaker 3 white

Speaker 17 power-structured media

Speaker 17 first criticized Harold

Speaker 3 for

Speaker 16 having been convicted of a tax violation.

Speaker 6 He failed to file his returns.

Speaker 2

We should be precise about this. It wasn't that he hadn't paid.

It's that he hadn't filed the returns.

Speaker 3 Henry filed the return, that's right.

Speaker 17 He'd paid withholding.

Speaker 15 Right.

Speaker 17 It was nothing to it.

Speaker 3 So, what difference is made?

Speaker 15 But the point is, when this occurred, it gave him publicity that he otherwise would not have gotten.

Speaker 16 Many people in the black community resented the criticism being leveled against him.

Speaker 17 They then said, well,

Speaker 19 you're not married.

Speaker 16 You can't be mayor if you're not married.

Speaker 19 We made Jane Byrne marry Mullen. We made Jim Thompson marry Jane Thompson.

Speaker 17 We made Kennedy in the Senate go back to his wife.

Speaker 16 You cannot be a viable politician if you're not married.

Speaker 19 Here again, he did something that blacks aren't accustomed to seeing blacks do.

Speaker 18 He stood up and he said, I'm not going to get married.

Speaker 3 Everybody thought, man, go marry Mary.

Speaker 16 If this is going to make

Speaker 16

not. Nothing can tell me to marry.

I don't want to marry.

Speaker 19 My marital status has nothing to do with my qualifications as mayor.

Speaker 19 And here again, the black community looked at him with a great deal more respect now because many of the people, black folks who married, don't want to be married no way.

Speaker 16 So they said, go on Harold.

Speaker 17 But he got some more publicity.

Speaker 16 And quite frankly, you will have to concede,

Speaker 19 I certainly will say it, that it had a white candidate with the same baggage been running, there's no way in the world he would have been elected mayor.

Speaker 2 How do you figure that?

Speaker 16 Well, that's true.

Speaker 17 Your white candidate who'd been in jail for failing to file the tax returns, who wasn't married, rumored being homosexual.

Speaker 16 Everybody know Harry wasn't a homosexual, but that was the rumor they tried to create.

Speaker 3 And a disbarred lawyer, no way in the the world

Speaker 15 he'd be elected.

Speaker 2 What should we think of that?

Speaker 17 What I think of it? I think it's here again, well,

Speaker 17 if South Africa can elect a man who's a felon.

Speaker 3 Nelson Mandela.

Speaker 17 Another Mandela for the same years.

Speaker 2 You know what's interesting about it is another criticisms also go to what the white fear was. I wonder,

Speaker 2 as far as you can tell, what was at the heart of the white fear?

Speaker 18 Because he's black.

Speaker 2 And so the two Chicago's headed to primary day. White Chicago, mostly ignoring the Washington candidacy, Black Chicago a buzz about it.

Speaker 2 And when he won, the two Chicagos had wildly different reactions, as you might expect. Monroe Anderson was a reporter at the Chicago Tribune at the time.

Speaker 2 He was one of the few blacks who worked in the newsroom the day after Harold Washington's primary victory.

Speaker 24 I mean, there was such a somber

Speaker 13 feeling around that place.

Speaker 24 I mean, it was like

Speaker 24 somebody's family member, beloved family member, had died or something. I mean, it was just really somber.

Speaker 24 And we were in this jubilant mood, except you did not feel comfortable expressing it, looking it. So we walked around,

Speaker 24 and then we would go into somebody's office or someplace aside and go, yes, jump up and down and then come out and walk around.

Speaker 32 Yes.

Speaker 32 We're reporters too. Yes, we understand it.

Speaker 2

After primary day, things got ugly. Usually, winning the Democratic primary for mayor in Chicago means you've won the office.

The Republican Party doesn't count in city elections.

Speaker 2 But in this case, as Chicago moved toward the general election in April 1983, 90% of white Chicago deserted the Democratic Party to vote for a Republican named Bernie Epton.

Speaker 2 One of his campaign slogans? Epton, before it's too late.

Speaker 2 Black Chicago saw the Democratic defections as racism, pure and simple. Meanwhile, white policemen circulated hate literature illustrated with chicken bones and watermelons.

Speaker 2 And in perhaps the most famous incident in the campaign, while stumping with Walter Mondale, Harold Washington stopped at St. Pascal's Church on the city's white northwest side.

Speaker 3 It was almost a riot.

Speaker 2 And Rao Anderson covered it for the Tribune. There's a racial slur in this next quote that we're leaving in, so you get the full picture here.

Speaker 24 When Harold showed up and the press entourage showed up,

Speaker 24 I mean, there was this, I mean, there was this angry, I mean, people were like

Speaker 24 approaching the car. I mean, it was just,

Speaker 24 people were out of control. I mean, they were,

Speaker 24

I thought that we were in physical danger. And then we get to the church, and somebody spray painted on the church, graffiti.

It said, die, nigger, die.

Speaker 2

On the Catholic Church. Yes.

Meanwhile, something curious happened. Occasionally, Harold Washington or one of his supporters would say in passing, something like, it's our turn now.

Speaker 2

And when they did, it made headlines. White Chicago and the mainstream press saw it as more than just ethnic pride.

It was seen as threatening.

Speaker 2 This is one of the ways that being a black politician in America is different than being a Polish politician or an Irish politician. Judge Pyncham.

Speaker 6 The difference is very, very simple.

Speaker 19 And that is, when the the Polish attempt to get a Polish mayor, it's good ethnic politics. When the Irish try to get an Irish mayor, it's good ethnic politics.

Speaker 19 But when the blacks try to get a black mayor, it's racism.

Speaker 2 Glenn Leonard grew up in the white southwest side of Chicago. Didn't vote for Howard Washington.

Speaker 27 I think a lot of people thought that he was going to bring in a lot of people that

Speaker 27

were going to be black and were going to change the city. Now we have our chance.

Now let's go ahead and do it.

Speaker 27

Let's right all these so-called wrongs, whether they were right or wrong, it's another story. Let's right these wrongs.

Let's move in. Let's take over.

Speaker 27

Let's have more of a say in the local government. And people just saw that as a threat.

They thought, well, these people are going to come in.

Speaker 27 move into the corner house and or whatever and another white flight starts again. I think that that was a big fear.

Speaker 2

Chicago will become another Detroit, people said, another Cleveland. Property values would fall, businesses leave.

Many whites had already fled one set of neighborhoods during white flight.

Speaker 2 Glenn says that white Chicago was used to having the late Mayor Daly protect their neighborhoods, for instance, by blocking federal schemes to bring in low-income public housing all over the city.

Speaker 2 Howard Washington wouldn't do that.

Speaker 27 He was going to obviously no longer block these, and these low-income housing units would come into every neighborhood in the city or whatever, and that would start the ball rolling your, what do they call it, on the the uh in the far east uh when the communist uh the domino effect thank you

Speaker 2 this is one thing that black politicians have to deal with the white politicians don't and this is true from chicago to washington dc from north carolina to south africa they have to deal with white fear howard washington we have 670 000 black medicine voters in this city When you get right down to it, the votes are here.

Speaker 12

They're here. They're here.

And every group, and I've said it before, and I'll say it again, and the press takes it and runs out left field with it.

Speaker 12

Every group that gets our percentage of population, they don't go around baking. They don't go around explaining.

They don't have any excuses to make.

Speaker 12

They just move on in and take one of their own and put them in office. That's what we should do.

That's what democracy is all about.

Speaker 2 Problem is, when your opponents don't see your election, it's just the normal workings of democracy.

Speaker 2

How Harold Washington tried to rise above their fear after he squeaked out a narrow victory in the general election and took office. That's in a minute.

Wayne Our program continues.

Speaker 1

Support for this American life comes from Mattress Firm. A good night's rest matters, but it's tough when every move wakes you.

Mattress Firm's sleep experts will match you with a bed for deeper rest.

Speaker 1 like the Temper Lux Adapt. Its temper material absorbs motion to minimize disruptions from partners, pets, or kids.

Speaker 1 For the great sleep you deserve, visit Mattress Firm and upgrade to a Temper-Pedic with Next Day Delivery. They make sleep easy.

Speaker 1 Restrictions apply, Next Day Delivery available on select mattresses and subject to location. See Store for details.

Speaker 1 Support for This American Life comes from 20th Century Studios, presenting Springsteen, Deliver Me from Nowhere.

Speaker 1 Scott Cooper, director of Academy Award-winning film Crazy Heart, brings you the story of the most pivotal chapter in the life of an icon, starring Golden Globe winner Jeremy Allen White and Academy Award nominee Jeremy Strong.

Speaker 1

Experience the movie that critics are raving is an intelligent journey into the soul of an artist. Springsteen, Deliver Me from Nowhere.

Only in theaters October 24th. Tickets on sale now.

Speaker 1 Support for this American Life comes from Charles Schwab with their original podcast, Choiceology, hosted by Katie Milkman, an award-winning behavioral scientist and author of the best-selling book, How to Change.

Speaker 1 Choiceology is a show about the psychology and economics behind people's decisions.

Speaker 1 Hear true stories from Nobel laureates, historians, authors, athletes, and more about why people do the things they do.

Speaker 1 Download the latest episode and subscribe at schwab.com slash podcast or wherever you listen.

Speaker 2 This is American Life, Myra Glass.

Speaker 2 If you're just tuning in today, what we're doing is that in this moment when a Democratic socialist, a Muslim candidate, Zoran Mamdani, stands poised to become the next mayor of New York, sending the Democratic Party into a kind of identity crisis as he does it.

Speaker 2 We're rerunning this show that we first broadcast back in 1997 about another big city mayor who forced the Democrats to re-examine what the party was all about and pick sides.

Speaker 2 Harold Washington, Chicago's first black mayor, who took the mayor's office in 1983 and died just four years later, just a few months into his second term. We rejoin that old episode now.

Speaker 2 So in Chicago and most American big cities, the way it used to work, and I say used to with some reservations, you could argue that a version of this still exists lots of places, but the way it used to work was that when Irish Americans took the mayor's office, or Italian Americans or Polish Americans, they channeled contracts and patronage jobs and other municipal goodies to their own communities.

Speaker 2 Lou Palmer was one of the people at the center of the movement to elect a black mayor in Chicago. He convened the early organizational meetings in his basement.

Speaker 2 It is hard to imagine that Harold Washington would have ever come to office without him. And he was disappointed by Harold.

Speaker 13 I don't know, but he never

Speaker 9 became

Speaker 9 what I would consider the black mayor.

Speaker 9 Black people wanted something that

Speaker 9 was so simple,

Speaker 29 fairness.

Speaker 9 And I used to get upset with Harold after he became elected because Harold

Speaker 9 was too fair.

Speaker 9 In fact, he would say in his speeches, you know, I'm going to be fair. I'm going to be more than fair.

Speaker 9 No one,

Speaker 9 but no one

Speaker 9 in this city,

Speaker 9 no matter where they live or how they live, is free from the fairness.

Speaker 12 of our administration will find you and be fair to you wherever you are.

Speaker 4 I used to cringe

Speaker 9 when he would say, I'm not only going to be fair, but I'm going to be fairer

Speaker 16 than fair.

Speaker 3 Well, come on.

Speaker 3 You know,

Speaker 13 you don't have to go overboard.

Speaker 13 And Harold did.

Speaker 9 Those of us who are considered radicals,

Speaker 9 we simply believe that

Speaker 9 since Dalies, the Dalies,

Speaker 9 Byrne and all the rest of the white males, had always put white people first without any question, without any apology,

Speaker 9 we said Harold got to put black people first, and that's what we wanted.

Speaker 9 I'm not sure we wanted

Speaker 9 to be to white people what Daly was to black people. That is, you know, he was just ridiculous.

Speaker 13 But people wanted,

Speaker 9 they wanted to see the opportunity to have our community thrive like other communities.

Speaker 2 It wasn't just black nationalists like Lou Palmer who felt this way.

Speaker 2 Old-time machine loyalists like Eugene Sawyer, it was the black Alderman that the white Democratic machine wanted to secede Harold Washington as mayor, said the same thing.

Speaker 36 And that was part of the thing that I think we probably were too fair.

Speaker 36 I think Harold was too fair.

Speaker 36 A lot of people think it was too fair by giving a lot more

Speaker 36 and giving everybody the same thing.

Speaker 13 And

Speaker 36 people didn't expect it. A lot of black folks think that, you know, you should have given your own people a little bit more.

Speaker 24 Well, a major problem with being a black person in America

Speaker 9 is you're in this trap.

Speaker 24 Because, I mean, and this is sort of

Speaker 24 our curse and our blessing because of this racial history, is that we have been complaining and pointing out all these inequities

Speaker 32 for a very long time.

Speaker 24 And therefore,

Speaker 24 all these things that you have pointed out that have been an injustice to you now that you're in power, you can't do because it would be injustice to whites.

Speaker 24 And therefore, the rules have to be this great, even, everything's fair and square.

Speaker 2 People close to Harold Washington say that it was smart politics for him him to be fairer than fairer.

Speaker 2 After all, black wards had been treated so unfairly in the past, and simply giving them the same services that the rest of the city got would be a huge step forward.

Speaker 2 It was also the political stance he felt most comfortable with by disposition.

Speaker 2 And when black politicians or community activists came to City Hall, trying to get more for one neighborhood over another, he was so enormously popular in black Chicago, where 85% of the black electorate turned out to vote for him, and where everyone simply referred to him as Harold that he could ignore the pressure.

Speaker 2 Jackie Grimshaw was a staff person.

Speaker 8 I think there's a difference between the black population and the black politicians.

Speaker 8 I think on the part of the black politicians, it was definitely it's our turn.

Speaker 8 And I had to deal with some of these folks. I mean, they'd come in and they want 10 jobs and crap like that.

Speaker 8

10 jobs. But I think on the part of the people, I mean, they were into fairness.

I mean, I think the fairness thing played with them. You know, I mean, they were proud of Harold.

Speaker 8 They supported him, what he was doing.

Speaker 2 Privately, Harold Washington talked about the danger of doing away with the old patronage system, how it could make the first black mayor weaker than any of his white predecessors.

Speaker 2 But publicly, for all intents and purposes, patronage was over.

Speaker 12 It's gone. It's gone.

Speaker 12 In the words of Cornell Davis, they said he wasn't dead.

Speaker 12 So I went to his grave, and I walked around on that grave, and I stomped on that grave, and I jumped up and down, and I called out, Patronage, Patronage, are you alive? And Patronage didn't answer.

Speaker 12 It is is dead, dead, dead.

Speaker 2 Washington attacked the machine. The machine struck back.

Speaker 2 From the first day of Washington's first city council meeting, 29 aldermen, all of them white, the old Democratic machine, teamed up to oppose him.

Speaker 2 For the first time in memory, a Chicago mayor did not control City Hall.

Speaker 2 For the first time in memory, clout, that's what we call it in Chicago, clout, sheer bullying force that was at the heart of Chicago politics, clout was no longer in the mayor's control.

Speaker 2 It was the machine's 29 votes to Harold's 21 votes. The 29 not only blocked his appointments, it never brought them up for consideration.

Speaker 2 It blocked most of his legislative initiatives and dedicated enormous energy to looking for ways to embarrass him and thwart him. It was Mayhem.

Speaker 2 A battle so divisive and chaotic that it sustained the animosity and suspicion between black Chicago and white Chicago for years.

Speaker 2 It came to be known locally as Council Wars, after a local African-American comic named Aaron Freeman began staging moments in local politics as scenes from the Star Wars trilogy.

Speaker 2 Harold appeared as Luke Sky Talker, leader of the rebellion, constantly spouting off long, difficult words.

Speaker 2 Harold's main political opponent, Ed Vredoliak, the alderman who led the 29, also got a big part.

Speaker 34 What are you doing in my office, Lord Darvs Vredoliak?

Speaker 34 I wish to discuss committee assignments for the new council.

Speaker 34

I don't have to talk to you. I'm the mayor.

I can do whatever I want. I can.

Speaker 34 I find your lack of respect disturbing.

Speaker 34 It is obvious you do not know the power of the clout

Speaker 34 it has served all of the mayors before you it can bring you great wealth and power or it can destroy you as easily the choice is yours

Speaker 34 You do not consternate me, Vridoliak. Take this parliamentary maneuver.

Speaker 34 Well done, Mayor, but I counter with this negotiated majority.

Speaker 34 Then I file a suit in court.

Speaker 34 But the decision is in my favor.

Speaker 34 You may have prevailed at this juncture, Vidoliac, but I will assiduously pursue your disestablishment.

Speaker 34 Perhaps, Mayor, but to do so, you must use the dark side of the clout.

Speaker 34 You must make deals and compromises.

Speaker 3 Never!

Speaker 34 Yes, Mayor, to defeat me, you must become me. Look at my face, Sky Talker, for I am your mentor.

Speaker 3 No

Speaker 2 Even under these adverse conditions, Washington did manage to pass budgets and get some things done. Black wards finally got the same street repair and garbage pick up as all the other wards.

Speaker 2 Jackie Grimshaw describes one scheme Washington came up with to do some improvements around the city, designed to be, of course, fairer than fair, to give every ward the same benefits.

Speaker 2 But the 29, of course, opposed it, and Washington needed their approval because to pay for it, he wanted to issue a city bond.

Speaker 8 So every ward was to get, I think, 10 miles of street resurfacing and alleys, a certain number of alleys done, and street lighting. And

Speaker 8 so he had all of these on the bond issue, and they were refusing to pass it. So he put all of the reporters on the bus and he would go around to these various wards.

Speaker 8 And we went out to Mountain Greenwood,

Speaker 8 another area of the city that

Speaker 8 did not welcome blacks at the time,

Speaker 8 to say, your alderman is refusing to support this bond issue that I want to use to give you real streets.

Speaker 8 And if you want it, you better tell your alderman to vote for it. And so, by the time he got through doing this, you know, the folks in the communities were pretty much outraged.

Speaker 8 You know, black mayor or not, they wanted their streets, they wanted their sewers, they wanted their vaulted sidewalks repaired and so forth.

Speaker 2 What happens to American politics when one of the politicians happens to be black?

Speaker 2 In this case, what happened was that everything in city politics was seen through the prism of race, even though often it had nothing to do with race. Often it had more to do with reform.

Speaker 2 Gary Rivlin is the author of a very even-handed history of Washington's years, Fire on the Prairie.

Speaker 28 You know, everyone wants to understand Harold Washington as the first black mayor, and it's true, he was the first black mayor, and that that was a very significant thing.

Speaker 28 But he was also the mayor who beat the Chicago political machine.

Speaker 28 He was the first reformer in 30 years to take on the machine, and he did it more successfully than anyone else before him, purely on a reform point of view.

Speaker 28 And so he was a different kind of politician, but no one could ever see

Speaker 28 beyond his race.

Speaker 29 In fact, there was a political cartoon at the time

Speaker 28 I loved, and it was an editor asking a reporter covering covering the election,

Speaker 28 so anything changed, anything new?

Speaker 28 And the reporter answered, nope, he's still white and he's still black. And really it was never,

Speaker 28 it really wasn't that much more sophisticated than that cartoon

Speaker 28 indicated.

Speaker 12

You pick up a local paper and these guys just wax so eloquent, they don't know what the deal they're talking about. Don't have the slightest idea about the phenomenon.

Don't understand the history.

Speaker 12

Don't understand the mindset. Don't understand what pushed people.

All they say is, gee, black black folks must be angry.

Speaker 12

Gee, black folks vote for black folks. They must hate white folks.

Ain't got nothing to do with nothing.

Speaker 12

Nothing. Crazy stuff.

But that's what you read around in Chicago. That's what I have to put up with every day when I look in the reporter's eyes.

Speaker 12 All those silly business, you know. How many white folks did you convert today, Harold?

Speaker 35 Wow!

Speaker 35 Wow.

Speaker 12 And the answer is more than you did, boy.

Speaker 12 Because I do my job, irregardless of race, color, creed, or sex.

Speaker 2 Because everything he did, even things that were more about reform than about race, was seen through the lens of race.

Speaker 2 It gave Washington's opponents a tool that they could use against him, which they did. A typical example.

Speaker 2 Some crime rates went up between 1985 and 86, even though overall crime was lower under Washington than under his white predecessor.

Speaker 2 But his opponents tried to make the case that this proved that the black mayor did not care about crime.

Speaker 2 Hate literature had said that he would do nothing about crime, because most crime is caused by blacks.

Speaker 28 So they were using this statistical

Speaker 28 bump between 85 and 86 to prove what the hate literature was saying that the black mayor is going to be indifferent to crime. See,

Speaker 28

that's playing the race card and playing it in a dirty way. It's a way of distorting statistics to play to racial fears out there.

So did Washington talk about race?

Speaker 28 Did he talk about the Chicago political machine?

Speaker 28 always being biased against the black community. Sure, is that playing the race card? Sure, but I also happen to think it's true what he was saying.

Speaker 28 Whereas what I think the opposition was doing much more of was playing the race card and playing it in a dirty way, you know, trying to tweak and abuse statistics any way they could to prove their point and play into the worst fears of the white community.

Speaker 28 I never saw Washington playing into the worst fears of the black community. In fact, his rhetoric was, I'm going to be fairer than fair.

Speaker 2 Fact is, by the time he died, just a few months into his second term of office, Harold Washington had put together a working majority on the council.

Speaker 2 Not many more whites voted for him in his second election than in his first, but every political observer in Chicago says that he was making headway.

Speaker 2 Patrick O'Connor was one of the 29 aldermen who opposed Washington, though he was one of the few swing votes who sometimes sided with the mayor.

Speaker 23 We invited him up to a picnic in our ward,

Speaker 23 and he showed up at our picnic, and

Speaker 23 he got a great reception.

Speaker 23 People that really didn't vote for him and probably wouldn't vote for him the next time respected the fact that he came out there, that he wanted to say hello, that he wanted to participate.

Speaker 23 And bear in mind that I was voting consistently with a bloc that was voting against him and he came out and we spent the day and it was fine.

Speaker 23 I remember one time we were both invited to a place that neither of us were particularly popular in the ward

Speaker 23 and so I got a call from his office and this is again at a time when there was a council war going on asking was I going to

Speaker 23 this

Speaker 23 festival or whatever it was and if I was would I meet the mayor on on a corner in our ward and go in there together with him? And I told the guy, no, I'm not meeting him on the corner.

Speaker 23

I said, he wants me to go. He's going to pick me up at my house.

So the mayor pulls up to the front of my house. He comes in.

Speaker 14 We have

Speaker 23 a glass of wine that he had, and I had a beer. And

Speaker 23

we sat around for a couple minutes. And he met my family.

And

Speaker 23

he looks in my dining room. We didn't have any dining room furniture at the time.

The kids were all young and we just moved into the house. So he says,

Speaker 23 he says, where's your dining room furniture? My wife says, you don't pay him enough money. And Harold goes, I knew this cheese was going to cost me something.

Speaker 23 I mean, and he was just that quick. He was really very, very good.

Speaker 23 But my point is, is that we got in the car, we went to this festival, and by the time he left, he had people dancing with him. He

Speaker 23 went over,

Speaker 23 he was talking with folks. By the time he left, it might not have changed the mind of everybody in there that he was okay.

Speaker 23 But he had made a significant impact.

Speaker 23 And he understood by keeping that schedule and going to areas where he was not expected to show up or would traditionally not be the most welcome person, that he was winning percentages of people.

Speaker 23 And that's all he had to do.

Speaker 2 Vernon Jarrett says that if Washington had lived, he would have done a lot to ease the strains of modern Chicago apartheid.

Speaker 22 Hell was going to win over

Speaker 22 a big chunk of the white population, and I don't mean Gold Coast liberals.

Speaker 22 They were beginning to like this guy, and they could see something in him

Speaker 22 that represented them. He was chubby, warm, friendly, and not only that, he was going into some lower-class white neighborhoods having their streets paved for the first time.

Speaker 22 And they were slowly beginning to lose their fear.

Speaker 2 Act two, the present and the future. Today's rerun, first broadcasted in 1997, 10 years after Harold Washington's death, continues.

Speaker 31 There are ways I think that the marriage changed the city forever, but they're not things you can necessarily measure by doing headcounts and using a lot of numbers.

Speaker 2 Laura Washington, Harold's former press secretary, now editor at a sort of muck-raking called The Chicago Reporter.

Speaker 31 I think he opened up the city in ways that it will never be closed again. If you look at the numbers, you'll still see a lot of inequity.

Speaker 31 You'll still see neighborhoods that are poorer, probably poorer than they were 15, 20 years ago.

Speaker 31 You'll see neighborhoods that still probably don't get their fair share of city services, but you'll see, I think, a dramatic difference in the attitude that public officials and policymakers have to equity in the city.

Speaker 2 Ten years after Harold Washington's death, people who follow politics in Chicago say that if nothing else, current mayor, Richard M.

Speaker 2 Daley, son of Richard Jay, has to worry about making black voters angry. He's been careful to have black press secretaries and kept a number of appointees from the black administration before him.

Speaker 2 He's done nothing so far to infuriate black Chicago the way his white predecessors regularly did.

Speaker 2 City services are distributed more fairly, even today, though there's been a bit of backsliding here and there. And Richard Daly's latest proposed bond issue follows the model of the Washington years.

Speaker 2 It gives all of Chicago's wards equal benefits, something that was unheard of in the years before Washington.

Speaker 2

Okay, so this is Ira in 2025 again. Hi.

At the end of Harold Washington's first term, 88% of white voters still voted against him.

Speaker 2 And 10 years after his death, when we first broadcast the program that you're listening to right now, we sent a reporter, Rachel Howard, to the 39th ward out near O'Hare Airport, a mostly white ward that voted against Washington, to see if times had changed, to see if they would consider voting for a black mayor.

Speaker 2 Short answer, no. Longer answer: she talked to people in a bar who got totally riled up as soon as she mentioned Harold Washington, called him the N-ward.

Speaker 38 They would start ranting about how he should have stayed on the South Side, how he wasn't there mayor. Ten years is not a very long time.

Speaker 4 No, I didn't vote for Harold at all. Why not?

Speaker 23 Because he was black.

Speaker 38

Most people I spoke with felt this way. Some even said they were scared when Harold was elected.

And in another bar up the street, a guy explained what everyone had been afraid of.

Speaker 39 He thought, that's it, we're done.

Speaker 39

That was a big thing. I mean, North Side is going to be a South Side now.

He said North Side and South Side are very segregated. Put it this way.

Speaker 28 He thought that the black people are going to take over the city.

Speaker 39 No, no, not that.

Speaker 2 Those slums would be slums.

Speaker 39 You know, you worry about slums.

Speaker 2 Okay, so that was 1997.

Speaker 2

But then we went back 10 years after that. It doesn't matter.

2007.

Speaker 2 And I have to say it was interesting to change.

Speaker 2 Reporter Rob Wildboar went to a bunch of the wards where Harold Washington was not welcome back in the day, the 10th, the 11th, the 23rd wards, and he talked to 50 people.

Speaker 2 And all but three of them said they would be willing to vote for a black mayor.

Speaker 2 Now, to be clear, people were openly racist, okay? Unapologetic about it. Like this guy, Pete,

Speaker 17 bought a house here in Hegwish, and what happened?

Speaker 3 Blacks moved in.

Speaker 13 Taking over the parks, taking over schools, taking over everything.

Speaker 3 Go on a holiday to Wolf Lake. Well, who's over there?

Speaker 40

They're all barbecuing over there. We can't even go to our own parks.

We got nothing.

Speaker 2

But then, the same guy said that he wished that a black alderwoman, Toni Prequinkle, would run for mayor. He voted for her, he said.

She did a great job cleaning up Hyde Park.

Speaker 2 There was a woman named Mary Kay, who lived in the 23rd Ward by Midway Airport, the neighborhood where Washington got the lowest vote total in the city in 1983, less than 1%,

Speaker 2 just 199 votes. Mary Kay was not one of the 199.

Speaker 2 She told her reporter Rob, things are just different now.

Speaker 41 Back then, for me, it was white or black.

Speaker 9 You know?

Speaker 41 I was prejudiced back then, probably. More so than I am now.

Speaker 31 There's still some lingering around.

Speaker 3 Oh, yeah.

Speaker 41 A little bit, you know.

Speaker 41 Don't turn my back on them, but yeah.

Speaker 41 No, I mean,

Speaker 41 that was 20 years ago.

Speaker 41 I don't have that fear

Speaker 41 these days.

Speaker 41 You know, now I accept you're black or white, you know.

Speaker 41 And Washington didn't do bad. I mean, he was a decent mayor.

Speaker 41 So what's changed?

Speaker 41 Everything.

Speaker 41 I mean, I've changed. They've changed.

Speaker 41 The black people are more educated. They're, you know, just in on something these days.

Speaker 41

They've come a long way in this world. And they deserve, you know, they worked hard.

I mean, you see it in the stores. You know,

Speaker 41

they're doing just as good as that. They're well-dressed.

They're, you know, they're clean.

Speaker 3 They're not the ghetto.

Speaker 28 And they want what we got.

Speaker 41 What we've always had.

Speaker 12 Every

Speaker 12

and if the press is listening, I want them to hear this. They didn't hear it when I ran for office.

I'll say it again.

Speaker 12 Every group, when it gets population ascendancy,

Speaker 12 as night follows day, decide, without malice to anybody, not anger at anybody, that it is their turn.

Speaker 12 Period. That's all.

Speaker 12 Ain't nothing wrong with that.

Speaker 12 I made that statement two months ago and they said it was racist.

Speaker 12 But they left out most of the statement, which the Irish do it, the polish do it the jews do it and every intelligent group on earth because every group does it and we do it and we should do it and we do it in a positive sense not in a negative sense you're not anti-irish because you're pro-black

Speaker 12 you're not anti-black because you're pro-Jewish I mean that doesn't follow you just happen to be pro and as long as you are not As long as you are not anti, as long as you are not anti, your pro-ism is accepted.

Speaker 12 It's just that something. Now I hope the press gets it right this once.

Speaker 2 Okay, so obviously that's Harold. And then before that was taped from 2007, voters speaking 20 years after he died.

Speaker 2

2007, that same year, you may remember, there was another black Chicagoan in politics. capturing people's attention.

Barack Obama was running for president.

Speaker 27 Some of you may know that I originally moved to Chicago in part because of the inspiration of Mayor Washington's campaign.

Speaker 42 And for those of you who recall that era and recall Chicago at that time,

Speaker 42 it's hard to forget the sense of possibility that he sparked in people.

Speaker 2 When Barack Obama ran for Senate and later for president, one of his advisors was David Axelrod, a man who's uniquely positioned to comment on how racial politics have changed in Chicago since Harold's time.

Speaker 2 Because he was also a political advisor to Harold Washington back during Harold's second run for mayor.

Speaker 2

Back in 2007, I reached Daxerat on his cell phone to talk about that. It was during the Obama campaign.

He was on a campaign bus in Iowa.

Speaker 2 He told me back then that things had significantly changed in Chicago's white wards in the years since Harold's death. I remember that the night of the 2004 Democratic primary for the U.S.

Speaker 35 Senate when Barack Obama was nominated. And one of the things that I looked at that that night was how he did on the northwest side of Chicago.

Speaker 35 You know, when Harold ran, he got 8% of the white vote in his first primary. I think he got 20% in the reelection.

Speaker 35 And much of the determined resistance was on the northwest side of Chicago.

Speaker 35

And Obama carried all but one ward. on the northwest side of Chicago.

He even carried the precinct in which St. Pascal's Church sits.

Speaker 35 That was the church where Harold Washington and Walter Mondale campaigned in 1983 and met with really hostile resistance from the crowd. Obama carried that precinct.

Speaker 35 And I said to Barack that night, I think Harold's smiling down on us tonight.

Speaker 2 When Obama got to the general election for senator, he won 70% of the vote or more in every white ward in the city. His results weren't far from that when he ran for president.

Speaker 2 Years later, when Kamala Harris ran against Donald Trump in 2024, that mostly held. Most of those white wards went solidly for Harris, with 60 or 70 percent voting for her.

Speaker 2 Trump only won one Chicago ward out of 50.

Speaker 2 When I asked the people who urged Howard Washington to run in the first place, that's Lou Palmer and Tim Old Plack, what the lessons of the Washington years are. They both said the same thing.

Speaker 2 They talked about how it was a mistake to think you could make the world change if you pin your hopes on just one man. After Harold died, the movement died too.

Speaker 9 And I tell you, a lot of people don't like to criticize Harold Orson.

Speaker 9 I blame Harold for this.

Speaker 37 What should have been happening, we should have anticipated either his demise or removal from office and been organizing for that possibility.

Speaker 9 Harold was put on a pedestal,

Speaker 9 and I think that was a major mistake.

Speaker 9 We lifted him to almost God status.

Speaker 2 Barack Obama noticed the same problem. In fact, there's a passage in Dreams from My Father about this when he writes about what Chicago was like immediately after Harold's death.

Speaker 33 The day before Thanksgiving, Harold Washington died.

Speaker 2 This is Obama reading on the audiobook.

Speaker 33

It occurred without warning. Sudden, simple, final, almost ridiculous in its ordinariness.

The heart of an overweight man giving way.

Speaker 33

It rained that weekend, cold and steady. Indoors and outside, people cried.

By the time of the funeral, Washington loyalists had worked through the initial shock.

Speaker 33 They began to meet, regroup, trying to decide on a strategy for maintaining control, trying to select Harold's rightful heir. But it was too late for that.

Speaker 33 There was no political organization in place, no clearly defined principles to follow. The entire of black politics had centered on one man, who radiated like the sun.

Speaker 33 Now that he was gone, no one could agree on what that presence had meant.

Speaker 2 I guess it's worth pointing out that this is what so many Democrats said when Barack Obama left office and Donald Trump came to power, that Obama and his team didn't leave the Democratic Party in proper shape to face the battles ahead.

Speaker 2 In 2017, after Donald Trump was elected for the first time, I checked again with David Axelrod.

Speaker 2 He told me that Harold might have been surprised that a black man was elected president just two decades after Harold won his second term.

Speaker 2 But he said Harold would not have been surprised at the backlash once that black man got to the Oval Office.

Speaker 2 Well, Today's program was originally produced back in 1997 by Alex Bloomberg and myself with Nancy Updike, Elise Spiegel, and Julie Snyder. Senior editor for this show was Paul Tuff.

Speaker 2 Production help from Rachel Howard, Seth Lynn, Bruce Wallace, B.A. Parker, Matt Tierney, Suzanne Gabbard, Stone Nelson, and Michael Cometay.

Speaker 2 Since we first put the show in the air nearly 30 years ago, four of our interviewees, Lou Palmer, Vernon Jarrett, Eugene Sawyer, and Judge Eugene Pinchum, have died.

Speaker 2 None of them lived to see a black man win the Oval Office. Or of course, what's happened since.

Speaker 2 We used archival footage today from the following sources, from Brian Boyer's film Harold Washington and the Council Wars, from Bill Cameron's taped recordings of Harold Washington's speeches and press conferences.

Speaker 2 We got tape from Chicago's Museum of Broadcast Communications, thanks to Bruce Dumont and the staff there.

Speaker 2 Also from Harold Gladstone and Jim Wycellis' film The Race for Mayor, from Bill Stamitz's film Chicago Politics at Theater of Power, and from WBBM's archival news footage.

Speaker 2 WXRT Radio gave us archival tape of Aaron Friedman's Council Wars satire, and WTTW-TV gave us archival footage of the 83 debates.

Speaker 2 In addition to all that, we'd like to thank Eva Baeza, who at the time was director of the Chernin Center for the Arts at the Duncan YMCA, and thanks to Gary Rivlin, who gave us advice throughout this production.

Speaker 2

We recommend his book, Fire on the Prairie. It's a great history of the Washington years.

Thanks to Hugo Tyrell and Dolores Woods. Our website, thisamericanlife.org.

Speaker 2

This American Life is delivered to public radio stations by PRX, the Public Radio Exchange. Thanks as always to the co-founder of our program, Mr.

Tori Malatilla.

Speaker 4 I'm Harris Glass.

Speaker 2 Let us close out today with a recording from the night of Harold Washington's second annual victory.

Speaker 2 Next week on the podcast of This American Life, Evan creates an AI version of himself and sends it into the world to see what happens.

Speaker 35 Jesus, I'm talking to AI right now.

Speaker 2 What makes you think that?

Speaker 25 I don't know, just the way you're talking, it seems a little stilted.

Speaker 2

I get it. Sometimes we all wear different masks.

Can people tell the difference between you and AI?

Speaker 3 Not always.

Speaker 2 That's next week on the podcast on your local public radio station.

Speaker 5

This message comes from Schwab. Everyone has moments when they could have done better.

Same goes for where you invest. Level up and invest smarter with Schwab.

Speaker 5 Get market insights, education, and human help when you need it. This message comes from NPR sponsor OnePassword.

Speaker 2 Secure access to your online world from emails to banking so you can protect what matters most with OnePassword.

Speaker 5 For a free two-week trial, go to onepassword.com/slash npr.