Who is the modern American dad?

Young men are more interested in becoming parents than young women are, and there's a growing number of single dads by choice. A look at modern fatherhood.

This episode was produced by Devan Schwartz, edited by Megan Cunnane, fact-checked by Melissa Hirsch, engineered by Adriene Lilly and hosted by Jonquilyn Hill.

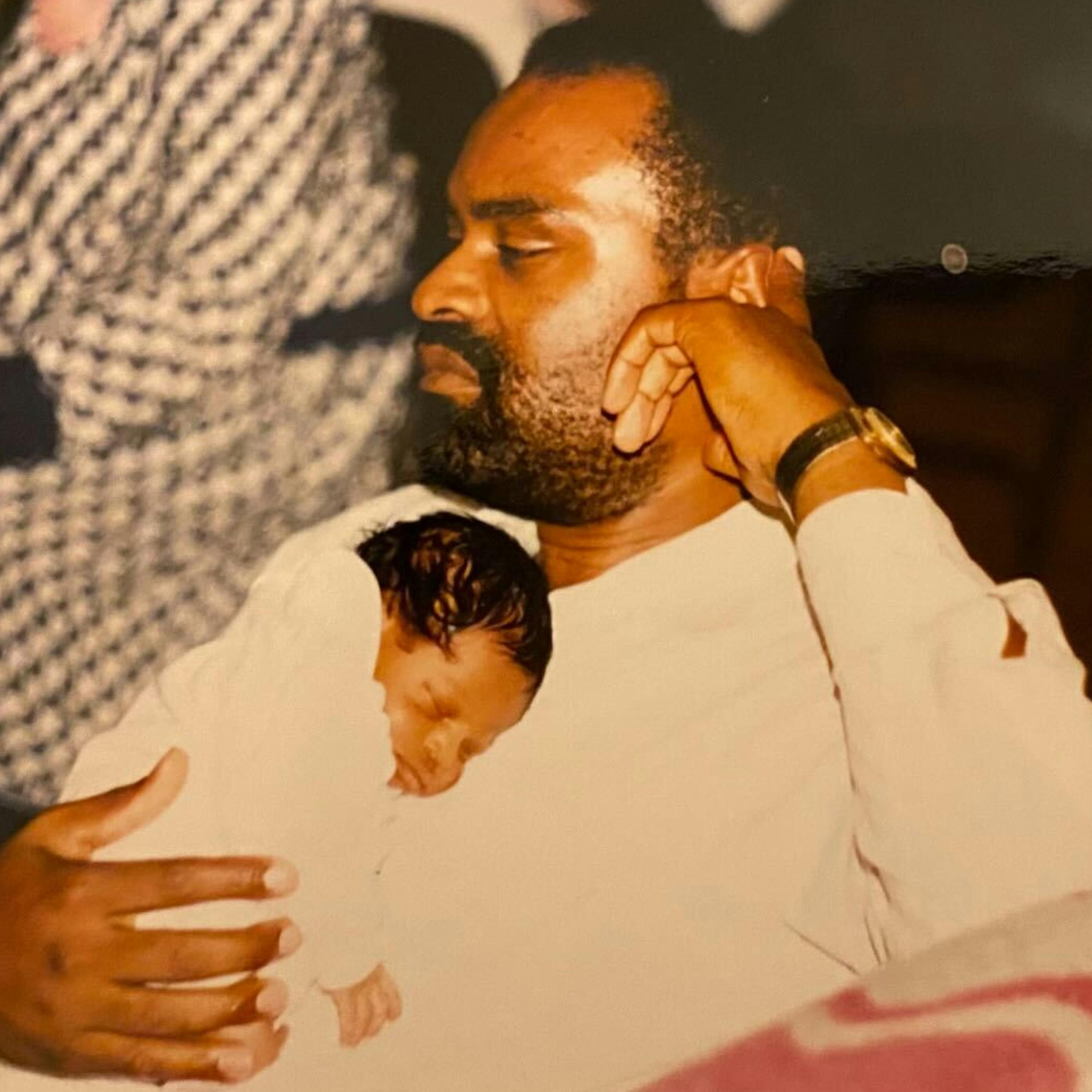

Thanks to Jonquilyn Hill for sharing a family photo for our episode image today. Image of dad John and baby Jonquilyn courtesy of the Hill family.

If you have a question, give us a call on 1-800-618-8545 or send us a note here. Listen to Explain It to Me ad-free by becoming a Vox Member: vox.com/members.

Learn more about your ad choices. Visit podcastchoices.com/adchoices

This episode was produced by Devan Schwartz, edited by Megan Cunnane, fact-checked by Melissa Hirsch, engineered by Adriene Lilly and hosted by Jonquilyn Hill.

Thanks to Jonquilyn Hill for sharing a family photo for our episode image today. Image of dad John and baby Jonquilyn courtesy of the Hill family.

If you have a question, give us a call on 1-800-618-8545 or send us a note here. Listen to Explain It to Me ad-free by becoming a Vox Member: vox.com/members.

Learn more about your ad choices. Visit podcastchoices.com/adchoices

Press play and read along

Transcript

Transcript is processing—check back soon.

Today, Explained — Who is the modern American dad?