947 - Laugh Now, Cry Later feat. Larry Charles (6/30/25)

Pick up Comedy Samurai here: https://www.hachettebookgroup.com/titles/larry-charles/comedy-samurai/9781538771549/?lens=grand-central-publishing

AND: get your pre-order in for YEAR ZERO: A CHAPO TRAP HOUSE COMICS ANTHOLOGY starting today at www.badegg.co

Press play and read along

Transcript

Speaker 1 I have to start the show with getting something off of my chest.

Speaker 1 I usually let these things slide, but this was pissing me off all last week, and we're often accused of using our platform to be petty little assholes, so I'm going to use this platform to be a petty little asshole.

Speaker 1 Last Monday, Derek Thompson of Abundance Fame called out Will for a very tepid joke and complained about our supposed unwillingness to engage in good faith with their whole project, saying, quote, they were pitched several times to our show.

Speaker 1 Now, I personally try to make it a point to read all good faith pitches we get and try to respond with an at least a let me check with the team.

Speaker 1 And I have gone through my own email and the Chapo email account and we received zero official solicitations from either Derek and Ezra themselves or any PR firm on their behalf.

Speaker 1 The only thing I got was in a DM from that Armand Domalewski guy saying, you should have them on. I could put you in touch, which I took as essentially a listener suggestion and politely declined.

Speaker 1 And even then, I provided him with some contact info for other left media that might be more amenable.

Speaker 1 But, like, Abundance guys, are you paying Armand or is he just freelancing Abundance PR for the love of the game?

Speaker 1

And either way, that's hardly a professional pitch, let alone we were pitched several times. And furthermore, Derek and I went to college together.

We've met several times.

Speaker 1

We have had more than one conversation over solo cups of old style. If he doesn't remember me, I remember him.

We have many mutuals.

Speaker 1

I have a hundred mutual friends with him on Facebook, just as an example of how in network we are. I am not hard to get in touch with.

I'm nice.

Speaker 1 If he really wanted to be on the show, a quick, hey man, it's been a minute.

Speaker 1 I've got this thing that might be interesting for the media property you produce would have been easy to get across my desk.

Speaker 1 And I would have left all of this alone, but for later last week, when everyone for fucking Jon Favreau to Adam Gentleson picked up Derek's pissy little crash out to bash our supposed obstinance.

Speaker 1 And to be clear, we would have said no to them, but to be much more clear, bitch, you did not even ask.

Speaker 4 So.

Speaker 1 I am tired of these dirtbag abundants just making up slander about the pragmatic left, especially at this time that they should be interested in building coalitions for their little program.

Speaker 1 And for all that, to bring back an old chap-o-bit, Derek, you are my plump, quacking duck of the week, and please fuck all the way off with this bullshit.

Speaker 3 One thing I'll give Derek credit for is that in no way will I ever engage in good faith with his ideological project.

Speaker 1 Well, you know what?

Speaker 3 That is your role on the show.

Speaker 1 My role on the show is to, in good faith, engage with pitches and bring them to you. And it is just galling to me to have that whiny, like, oh, they wouldn't have us when he, there was no reach out.

Speaker 1 Anyway, I had to get that off my chest.

Speaker 3 It's not that often that's something, you know, as Michael Jordan said, and I took that personally.

Speaker 3 And as Michael Jordan also said, fuck them kids.

Speaker 3 Hello, everybody. It's Monday, June 30th, and we've got some choppo for you.

Speaker 3 At the end of today's show, we'll be making a very exciting announcement that you'll be hearing about from us incessantly for the upcoming month.

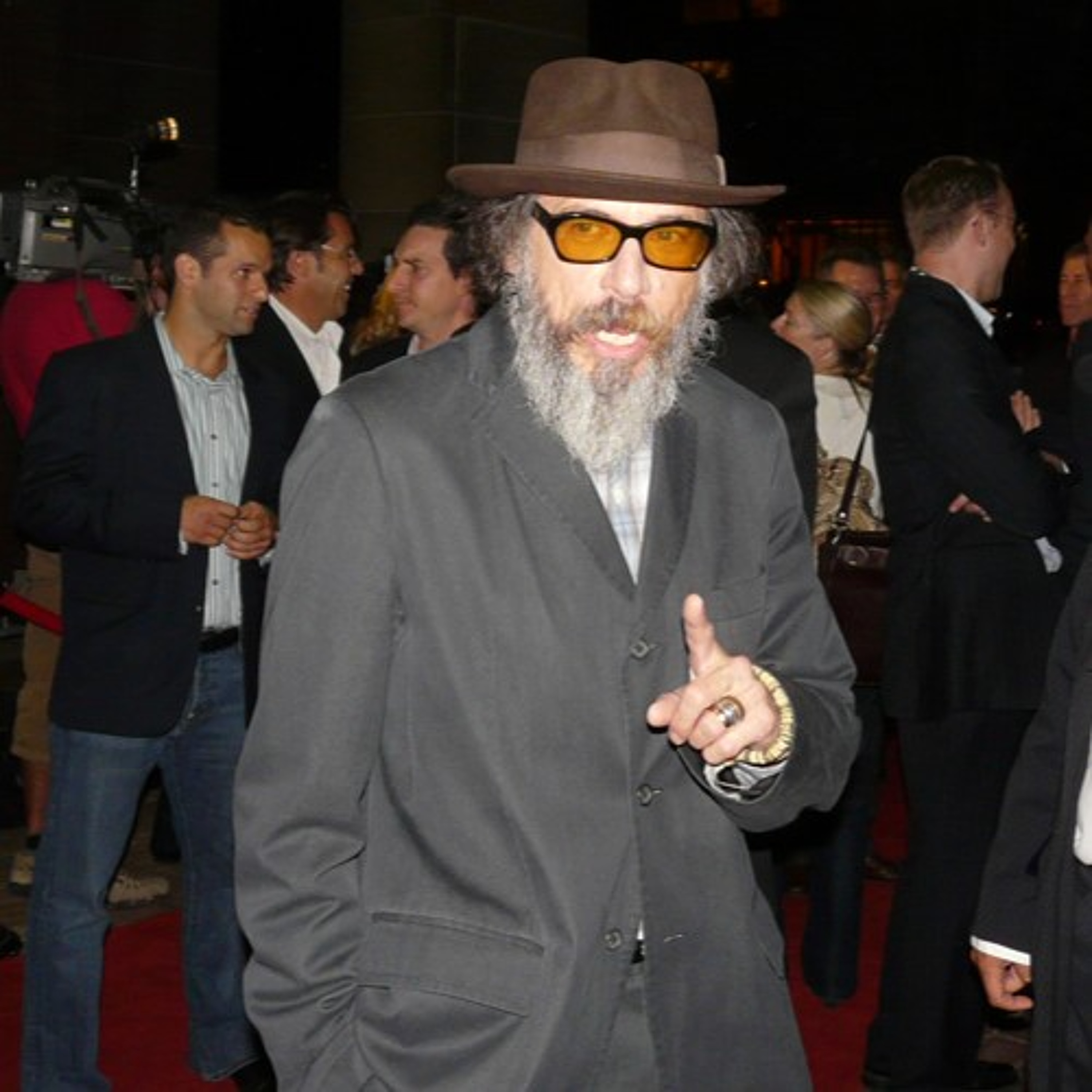

Speaker 3 But before we get to that, Felix and I are joined today once again by the great Larry Charles to talk about his new memoir, Comedy Samurai, 40 Years of Blood, Guts, and Laughter.

Speaker 3 Larry Charles, welcome back to the show.

Speaker 2 Thank you so much for having me. It's really exciting to be here.

Speaker 3 Larry, the title of the book is Comedy Samurai. And it's been said that a samurai must meditate every day on death and each day imagine oneself as dead.

Speaker 3 Does a comedy samurai also consider life and death in such terms?

Speaker 2 Death is probably my biggest theme, actually.

Speaker 2 I've always, all my comedy has been surrounded by death. I've always found death to be a perplexing subject worthy of comedy.

Speaker 2 And so death and comedy go together hand in hand as they walk off into hell.

Speaker 3 Well, I mean, yeah, when I read the book, I was really struck by this connection between comedy and death, which I think undergirds a lot of your story here.

Speaker 3 And if existence is a joke and the punchline is always the same.

Speaker 3 For you, like, what comes across is that comedy is a way that we discern meaning from it. And like,

Speaker 3 is that how you relate to it?

Speaker 2

Well, it's a way I think that fear is a big force that drives comedy. And I think death is something that we fear.

And so this is comedy becomes a way to process our greatest fears.

Speaker 2 And death, there's no greater fear than death, I suppose, at least for me. And for a lot of comedy people, I think.

Speaker 2 We have our egos. It's very hard to let go.

Speaker 2 It's very hard to shed that ego and get in touch with our nothingness and our essence and our place in the universe and um the fact that it ends makes no sense that's the one of the greatest absurdities that you go through all of this angst and these challenges and conflicts and then it ends what's the point

Speaker 2 so the the from beckett to mel brooks i think that question keeps coming up you know and it's a very absurd kind of uh equation that we all must uh deal with at some point.

Speaker 4 That part of the book, it reminded me of one of my favorite jokes that I've ever heard in my life. It was like, shit, like 14, 15 years ago at this point, but it was like a week or two after

Speaker 4 my dad died and my mom like got us all iPhones.

Speaker 4 And she like, I went to the Verizon store with her and like right when we got it, like right, right, right when we were leaving and I was like taking it out of the box, she said, don't you wish your dad died every day?

Speaker 2 And

Speaker 4

I have always thought about that joke. It's really funny.

Like my mom is an incredibly funny person, but I never really made the connection between the two concepts until this. And it is very true.

Speaker 4 I mean, not just for the

Speaker 4 joke maker himself, but

Speaker 4 I think for the audience.

Speaker 4 I mean, I think the most difficult thing with comedy, the thing that makes it ephemeral, is when you break it down in its most fundamental forms, the only way a joke can work is if for at least the duration of it, the audience can think in the same way that the person telling the joke does, that they can at least understand their interiority.

Speaker 4 That's the reason why it's so difficult and also why it's so fleeting that

Speaker 4 shared interiority doesn't, it isn't as

Speaker 4 lengthy or procedural as like a novel or something. But

Speaker 4 there's such a big connection with death because it is one of the only things where everyone generally feels the same thing.

Speaker 2 Well, kudos, first of all, to your mom, who does have a great sense of humor, because to be able to make that joke in that situation, instead of somebody else making it and her being horrified by it, that is a true comedian.

Speaker 2 She understands that the laugh, how important, how much of a healing tool in a way that laugh can be, you know, And it's true. It caught you guys by surprise.

Speaker 2 It might have even caught her by surprise when she said it. And that's another element of this comedy thing is saying something that no one was expecting.

Speaker 2

There are times when comedy needs to be predictable. You want to see the person trip over the thing and fall.

And there's a kind of an anticipation and then the delivery of that.

Speaker 2 But the surprise laugh, the thing you could not have possibly anticipated,

Speaker 3 that comes from a very deep place and that's a very powerful lap and usually has some kind of in my belief a chemical reaction that's positive inside your body yeah well it's this it's this sense that uh in the introduction you you write i took a violent approach to comedy laughter had to hurt laughter had to kill you said it was like a matter of honor shame and humiliation and it like like like a true samurai but like it's this connection between uh like for me like what is the our worst fear as you said like fear is an important part of comedy but it's also like what's most horrifying to us about life is what's the most funny and do you remember like like an ear like uh like the first time you sort of uh conceptualize that or that you like grasped for humor as your sort of sword and shield to sort of deal with the uh you know the uh

Speaker 2 the horrifying experience of being conscious in this universe well i think the first time or the or the first uh period when I became conscious of this was when I was a kid growing up in Trump Village in Brooklyn, which was a lower-income housing project built by Fred Trump.

Speaker 2 And Fred Trump and Donald would be wandering around and Fred Trump looked like Satan. And Donald,

Speaker 2 if you've ever seen a picture of him, I'm not even exaggerating.

Speaker 2 He's exactly what you imagine Satan to look like with the kind of mustache and the, you know, very fake looking hair yeah yeah yeah yeah yeah and a kind of a very you know evil eyebrows and an evil smile you know and donald was like donald today you know he was like uh this he was just a 14 or a 16 year old version of what he is today you know with the bad hair and the suit um but my neighborhood was kind of like uh it was built all the buildings the seven buildings were built at the same time and everybody moved in at the same time and that caused this demographic explosion So, all these boys moved into this neighborhood at the same time, and it became like the playground, the park was like a prison yard, and it was very much like Lord of the Flies, you know.

Speaker 2 And if you couldn't survive, you were going to go down, and every weakness would be used against you. And one of the only defenses that a person like me had,

Speaker 2 because violence was not really a solution for me, was humor. I was forced to kind of verbalize in some ways my fears and make people laugh and disarm them through that laughter.

Speaker 2

And a lot of kids use that. So that fear thing, that violence was met with humor.

And that was probably the first place that I became very conscious of it.

Speaker 2 And one of the first adult books I bought, which was in sixth grade, walking down Brighton Beach Avenue at a secondhand bookstore for a quarter was Catch 22.

Speaker 2 And And Catch 22 was a book that I didn't know anything about. It just looked interesting from the paperback, you know, on the back.

Speaker 2 And they used to give you a little synopsis on the back of the paperback. And that book also showed me, wow, you could actually be funny about war and death and maiming and dismemberment.

Speaker 2 and pain and suffering and all those things and make it like a legitimate thing, like in a book.

Speaker 2 So those factors, I think, were very key to developing my sensibility also my father was a failed comedian um and his uh his professional name was psycho the exotic neurotic and

Speaker 3 well i mean i as far as like like a literary influence couch 22 is is is you know been been huge for me too at like a similar age because it's not just that you can make something about war and death funny but in fact something about war and death can be funnier than anything else.

Speaker 2

Yes, yes. Well, it taps into, I mean, I would say that this is true of something like Borad also.

It taps into a forbidden place, like Felix's mom.

Speaker 2 It taps into a place where you should not be laughing. This is not funny, but yet

Speaker 2

that makes it funnier. That makes it more forbidden.

That is a there's a catharsis in that. And I've always been attracted to comedy that shouldn't be funny.

That's the greatest challenge to me.

Speaker 4 Catch 22, that part reminds me, I mean, I think a lot of people in this general line of work, that was a foundational book, or at least the concepts in that book, because it's also,

Speaker 4 that is around the age where you can actually start to understand literary irony, too.

Speaker 2 Like absolutely. Yeah.

Speaker 4 It informs like a sense of humor past just like the things that you know as like a 12 or 13 year old.

Speaker 2 Yeah, although as a 12 or 13 year old, you're also kind of trafficking in what we used to call sick jokes, you know,

Speaker 2 you know, mother jokes or kids without limbs jokes or, you know, dead.

Speaker 3 Dead baby jokes.

Speaker 2 Yeah, yeah.

Speaker 3 So you are you sort of collect them at that age.

Speaker 2 Yeah, exactly. And you are kind of already processing, you know, why is this funny? You know, and yet it is.

Speaker 3 Well, I mean, it's a way of sort of conceptualizing your own mortality.

Speaker 2 Exactly, exactly.

Speaker 2 So right from an early age, I think most kids are exposing themselves to it, and some walk away kind of developing a sense of humor based on that, and others walk away horrified and never wanting to deal with that kind of subject matter again.

Speaker 3 Well,

Speaker 3 you bring up where you grew up in Brooklyn. And like, I think in that story about, you know, seeing Fred Trump walking around looking like Lucifer and where you grew up in Brooklyn.

Speaker 3 I think there are like these two threads that unite there of like these currents of comedy in American life.

Speaker 3 One of them being like the comedy triangle of Brooklyn when you grew up that produced like you, Mel Brooks, Larry David, so much of American comedy and this kind of comedy of discomfort, this comedy of like a sort of a your armor and staff that you can like protect yourself from the world, but also kind of get revenge on it.

Speaker 3 But back to this idea that life is is an absurdity and that life is a joke. You also have Donald Trump himself speaking of things that shouldn't be funny, but are.

Speaker 3 At the end of the book, you write about like people, I suppose, perhaps best embodied in our current president, who do view life as a joke because ultimately there are no consequences for them.

Speaker 3 And it means that you can hurt anyone and do anything and it doesn't matter.

Speaker 3 And then the opposite of that is to like take the start from the same premise, but come to a completely different conclusion, which is that the meaningless, like you have to find meaning in life.

Speaker 3 And there has to be like

Speaker 3 life is the joke, but like comedy is the meaning. So, like, what do you see as a difference here between like those two sort of New York sensibilities as it relates to comedy?

Speaker 2 Well, I think in some ways, Trump, unlike me or most comedians, I think, or comedy writers, he has dismissed at least as much as he can the concept of death.

Speaker 2 You know, I think he is not that he's not afraid of it, but he is in denial.

Speaker 2 And I think think the denial has allowed him to sort of do these outrageous things and not really feel the consequences of it.

Speaker 2 Because he kind of has a sort of, and look, his family all live to be very old. You know, Fred Trump, Lucifer himself, might even still be alive for all I know.

Speaker 2 And so

Speaker 2 I think that denial in some way of his mortality has kind of fueled a lot of

Speaker 2 his sort of arrogance about it. And he has no humility whatsoever.

Speaker 2 And whereas the comedy writers who are very much in touch with that mortality, with that temporariness, that temporary quality of life have a certain humility about it as well.

Speaker 2 And that might be the distinction there, possibly.

Speaker 4 Yeah, I think that's a very good insight. I mean,

Speaker 4 everything that I've ever heard about like Trump's, whenever he talks about like, you know, personal health or just his general beliefs about like fitness or whatever, he's the closest thing we have to like one of those Chinese emperors that drink mercury because they thought it would make them immortal.

Speaker 4 And yeah, and it's like, it's obviously like it's ridiculous and hilarious, and it's sort of like

Speaker 4 him being a product of his time in a way,

Speaker 4 even though I don't think a ton of 80-year-olds think that like exercising depletes your body's finite amount of energy that you have for your entire life.

Speaker 4 But

Speaker 4 it does betray a

Speaker 4 fear of fragility.

Speaker 4 And

Speaker 4 kind of, I don't know, sometimes when you hear someone who has such ridiculous opinions about all of that, they love opining on it. It shows that they are avoiding looking at it at a deeper level.

Speaker 2 Yeah. Well, let me, let me, I agree with you, and I'll give you an illustration of this theory because there are comedians, like for instance, when I was younger,

Speaker 2 I used to write for a comedian named David Steinberg. And so I wind up like at the Tonight Show with him when I was a kid and meet Johnny Carson, or I would see George Burns or Jack Benny.

Speaker 2

or a lot of these guys and my theory and even like Billy Crystal, who I've worked with, I've seen the effect. And I think Trump also benefits from this.

And follow this for one second.

Speaker 2 The live performance, and you guys do live performances also. So you know, when you get that love from the audience, it's like a chemical reaction.

Speaker 2 You know, I think science hasn't studied this, but if you ever notice, comedians like Jack Benny or George Burns or Donald Trump live very, very long lives because they expose themselves to large doses of adulation.

Speaker 2 And something happens chemically inside of them. It like de-ages them or something.

Speaker 2

And I think that is part of the Donald Trump formula. It's very similar to the old comedians.

And there aren't that many around like that anymore. They don't.

Speaker 3 I mean, Mel Brooks did just turn 99, right? Right.

Speaker 2

There you go. Mel Brooks is 99, exactly.

And he allows himself to go and sit on a stage. and or stand on a stage and accept awards and get accolades and he gets this unadulterated, unabashed love.

Speaker 2 And somehow or another, that is a longevity tool for those guys. And I think Trump avails himself of the same thing.

Speaker 4 That specific feeling that

Speaker 4 you get from

Speaker 4 a completely enraptured audience, I think it's pretty similar to anabolic steroids in that, you know, for, you know, for most people, when you look at what anabolic steroids actually do,

Speaker 4 and in a lot of instances, why a lot of them were created, in some ways, it's like a miracle drug.

Speaker 4 The reason that most professional athletes take them is because you can recover from injuries at a superhuman clip. You can train, you know, four times a day and

Speaker 4 just

Speaker 4 be fresh enough to go again the next day. But for some people,

Speaker 4 it's incredibly dangerous. Steroids don't change your personality, but they just make you you, but more so.

Speaker 4 So if there's like a Latin resentment or aggression there, it's probably going to come out, especially if you're abusing them, especially if you don't have one of those great steroid doctors.

Speaker 2 Well, also, I was just going to say, if you stop using them, you also, there's that shrinkage that goes on, too.

Speaker 2 I mean, I've seen that when I used to go to the gym, I used to go to Gold's gym, and you would see guys

Speaker 2

pumping up for these contests. And then when the contest was over, they would shrink back.

It was almost like a Hulk kind of effect. Oh, yeah.

Speaker 2 Yeah. And I think the same thing is true with these.

Speaker 2 If Trump suddenly stopped going in front of audiences and stopped having rallies, I think he would shrink probably. And that would probably be the beginning of the end for him.

Speaker 4 Oh, yeah, I completely agree.

Speaker 4 But I also, the other thing I was going to say about it is that we've done this for like 10 years, and we've seen a lot of, you know, people in the general like internet, internet bullshit sphere, like come and go and, you know, change and, and, uh, you know, sometimes for the better, sometimes for the worse.

Speaker 4 And the worst thing for some people is

Speaker 4

validation. And that, you know, in an enraptured crowd is like, it is the highest form of validation.

And it's probably, in a lot of instances, made some of these people more insane.

Speaker 2 Yes. Well, I mean, using Trump as that example, I mean, you could really make that argument.

Speaker 2 He's gotten much worse as he's gotten more, because again, he has put the audience into some kind of trance, also, you know?

Speaker 2 And so there is this weird interaction, this chemical, you know, kind of reaction going on between him and the audience. The audience is getting something out of it too.

Speaker 2

They have a need to sort of adulate, if that's a word. And he has the need for the adulation.

And so it's a perfect symbiotic relationship, you know? Yeah.

Speaker 3 Larry, like you mentioned, like the memoir really is like a a tour through the the the history of American comedy.

Speaker 3 And I want to get back to this, like where you grew up and like the comedy triangle of Brooklyn.

Speaker 3 And like you and these guys who who went out to the West Coast to become comedy writers and really like defined like for what my lifetime is, like what American comedy was.

Speaker 3 Do you think there's anything quintessential about the Brooklyn you grew up in and like the Brooklyn Jewish community that you and like Larry David came out of? That like,

Speaker 2 what is it about that experience that lent itself to like creating the comedy of like the latter half of the american century well it was a like a kingston jamaica of comedy it really was i mean it's like why this little area produced so many comedy people because there's a lot of them uh beyond even um larry david and mill brooks and myself and woody allen is really from that area uh lenny bruce is really originally from that area So there's a lot of people that you could point to who are from,

Speaker 2

you know, even Andrew Dice Clay is from Sheepsaid Bay. They're It's all this little small little area of Brooklyn.

And why is it an interesting question? I've thought about it quite a bit recently.

Speaker 2 I mean, I think there's a couple of things going on. First of all, incredible density of population, all kind of up from the same place, from Russia, from Poland.

Speaker 2 The first generations of the people living in those neighborhoods were from Russia and Poland. They were escapees.

Speaker 2 from pogroms and you know the holocaust or whatever it was that was uh again, facing death. And so they were escaping death, really, is what they were doing.

Speaker 2 And they came to America, you know, and that sense of relief is kind of exhilarating in a way. Also, there's this Talmudic sort of tradition of

Speaker 2 Jews sitting around and arguing about ethics. Why is this right? Why is that right? What if we did this? What if we did that?

Speaker 2 And I think in that kind of, those kind of discussions, humor was really kind of being born in a way, at least amongst that group.

Speaker 2

I think the idea of arguing and being contrarian about kind of important life questions led to hubris responses at times. And I think that's part of it also.

So it's this combination of things.

Speaker 2 And also,

Speaker 2 we were forced. sometimes against our will, but often not, to read,

Speaker 2 whether it was reading the Torah or the Talmud or reading great Yiddish writers like Isaac Bashiva Singer, who used humor to tell his stories.

Speaker 2 They were bitter, they were ironic, they weren't necessarily laugh out loud, but they sort of prepared you for this absurdity that we're talking about.

Speaker 2 And I think for a lot of the people from that neighborhood, they were very conscious of the absurdity.

Speaker 2 even if they weren't professional comedy people, they were conscious of the absurdity of the life they had

Speaker 2 come from, the life they had come to, and then the rituals they were still kind of involved with, the seders and the going to the temple and all that stuff, and all those, you know, rapping to fill in.

Speaker 2 All these things are kind of silly. And yet, you know, they did them and they followed the rules, but they also recognized, at least some of them, the absurdity of it as well.

Speaker 3 Well, I mean, you're coming out of that.

Speaker 3

tradition. You're born out of that on the East Coast.

Then you go out to LA and you find a new set of absurdities and rituals and traditions.

Speaker 3 And in the book, you write that the very first joke you sold was to Jay Leno. And I'm wondering if you remember what the joke was.

Speaker 2 The joke was something like,

Speaker 2 at the time, there was a commercial on TV about Delta Airlines, Delta, the airline run by professionals. And my joke was, what do they have on the other airlines? Amateurs?

Speaker 2 You know, it was, it was something along those lines, maybe a little bit better than that one.

Speaker 2 And I got paid on consignment also. He didn't, you know, he said i'll try it out and if it gets a laugh on stage i'll give you 10 bucks and he got a laugh and so i got the 10 bucks

Speaker 2 you didn't get a ride in one of his like vintage automobiles well eventually he was he was very nice to me and very generous and again at that time at the comedy store that was another kind of coincidence a lucky break that the comedy store at that time was a kind of it was a golden era of the comedy store you had richard pryer there you had uh robin williams they were both trying trying out material constantly there.

Speaker 2 And the two big comedians, ironically, the two biggest comedians were David Letterman and Jay Leto. They were the twin gods of the comedy store.

Speaker 2 And David was very sort of, you know,

Speaker 2

he was more distant, hard to get close to. But Jay was very much, as you can imagine, he was like very people oriented, very much of a people pleaser.

And so he was very nice to me.

Speaker 2

And I actually went to his apartment a few times. And he had a garage even then and he has some classic motorcycles and cars shoved into that garage.

So I did see them.

Speaker 2 I did get a ride occasionally, but not for very long.

Speaker 3 Well, early in the book, like your, your first sort of your breakout like into comedy writing was on the TV series Fridays, which is sort of the like the off-forgotten

Speaker 3 like because you know Saturday Night Live is the institution, but Fridays was really like this legendary cachet of comedy talent and really like the beginnings of Seinfeld and Kerber Enthusiasm because it was you, Michael Richards, and Larry David.

Speaker 2 What was Friday's?

Speaker 3 Like what was that experience like for you?

Speaker 2

Well, it was interesting. I had been, you know, I had been a bellhop in a parking valet.

Literally, those were my two jobs before I got that job.

Speaker 2 And so when I got that job, even though I didn't, I was thrilled and excited and making 10 times more money than I ever made.

Speaker 2 Me and the other writers were all a fairly radical bunch, including Larry David and Michael. And we really wanted the show.

Speaker 2 We were like desperate to make sure the show was not perceived as a Saturday Night Live ripoff.

Speaker 2 And the first thing the producer said to us was, you know, why don't you go guys go sit down and come up with some titles for the show so it won't be mistaken for Saturday Night Live. And we went.

Speaker 2 And we all went off. You know, we were influenced by Monty Python and all these kind of very obscure esoteric things at the time.

Speaker 2 And we came up with all kinds of crazy names for the show, even like symbols like prints you know we had like just a show with just a symbol for the name you know and then we came back a couple of days later and we came into the writer's room the binders our jackets the stationery everything said fridays and so clearly they had made the decision and i think in some weird way that sort of uh motivated us to make sure that we did everything we could as writers at least.

Speaker 2 I don't think the actors were quite as radical as the writers, including Larry and Michael.

Speaker 2 The writers wanted to make sure that everything they did would be, would go as far and be as transgressive as possible to set it apart from Saturday Night Live.

Speaker 2 And again, we didn't fully succeed, but that was the goal, especially because we now were saddled with this title. that made it immediately a Saturday Night Live ripoff.

Speaker 3 What were some of the things you tried to come up with to be like to sort of break the form and differentiate Fridays from Saturday Night Live?

Speaker 2 Well, we did a lot of,

Speaker 2 you know, on Saturday Night Live, the most interesting sketches often were the ones that were on at the end of the night, you know, as it got close to one o'clock in the morning.

Speaker 2 And we wrote a lot more of those kind of absurdist sketches that were sort of more

Speaker 2 Ionesco, you might say,

Speaker 2 than they were like sort of a vaudeville, you know, and we were like trying things, we were experimenting a lot of synthesis of different forms together, cut-up technique almost, like William Burroughs.

Speaker 2 Burrows,

Speaker 2 yeah, trying to create a new form of sketch, you know.

Speaker 3 And that was. Probably the chief example of that is the famous Andy Kaufman incident on Fridays, where he came in and like, you know, and reading the book, I wasn't aware of this.

Speaker 3 Like, he made clear up front that I'm going to break one of these scenes.

Speaker 3 Like, that was his intention, was to just like and have the actors and like the audience not be aware of what's really going on here.

Speaker 2 That's right. That's right.

Speaker 2

He was really like a guru of comedy at that time. I mean, he was so avant-garde.

He was a performer. He was a performance artist, really,

Speaker 2 more than a comedian, but he did it. What made it so ballsy, so courageous, was that he...

Speaker 2 did performance art in front of nightclub audiences, in front of comedy club audiences who were drinking and expecting jokes.

Speaker 2 And he would upend every expectation you could possibly have about comedy to the point that people would be booing him. And that would be the response he really wanted to get.

Speaker 2 You know, he was not afraid of failure, which is such a key theme in comedy as well. And he came to the show and he asked, he said, this is what I would like to do.

Speaker 2 And we, being the transgressive group that we were, absolutely embraced it immediately and just tried to figure out the best way to do it. And that's how it turned out.

Speaker 3 Uh, you also describe how uh Andy Kaufman, uh, just as a bit, worked at a worked as a bus boy at a famous LA diner, and you would be getting lunch there with your manager, who was also Andy Kaufman's manager, and he would come and just like clear the water glasses off your table.

Speaker 2 It was amazing.

Speaker 2 I mean, we used to go actually, just to be perfectly accurate, we would, it would be after the Seinfeld episode that we taped, and Jerry and Larry and I, and maybe one or two people, and George Shapiro, who was andy's manager and jerry's manager we would go to this place jerry's deli in the valley just you know the same name as jerry but not no connection and we would have uh you know a late night bite there and andy would be doing a shift he would literally be doing a shift at jerry's deli as a bus boy no laughs no trickery

Speaker 2 i mean if if you needed the water to be filled he filled the water you needed coffee he would give you coffee. He would clear the table, but no laughs, no interaction whatsoever.

Speaker 2

And he did it for an eight-hour shift without breaking. It was pretty amazing.

And we would just be astonished that he was doing this.

Speaker 2 But again, that was part of what made him such a unique and original performer. Yeah.

Speaker 4 I think he used to be more heralded.

Speaker 4 I heard people talk about him a lot more like 10, 20 years ago. But I think especially today,

Speaker 4 he's sort of underheralded as someone who made

Speaker 4 a lot of contemporary, more like ironic,

Speaker 4 like Tim and Eric type stuff possible.

Speaker 4 And

Speaker 4 he's always talked about in these terms of like, you know, him being this definitive break from what was

Speaker 4 what was available at the time.

Speaker 4 But there's also, there is something very fundamentally pure about it, too, in that if you're doing that for eight hours and the people you know, like maybe aren't even going to come in that night, the only reason you're actually doing it is because it's funny to you.

Speaker 4 Yes. That seems that was like the, that seems to be like the fundamental thing with everything that just if it's funny to you, it's worth doing.

Speaker 4 And then maybe eventually it'll be funny to other people.

Speaker 2

That's really true. Yeah.

That's very true. I really, I I think that's a really good point.

I think that it was a, it was kind of

Speaker 2

an experiment. It was an art piece.

He wanted to see, he was interested in what would happen when people didn't laugh.

Speaker 2

Or, you know, he was interested in questions that normally weren't asked in comedy. And I thought those are very bold questions.

He was very...

Speaker 2

you know, for lack of a better term, anti-comedy. And he wanted to see what would happen.

And he was willing to deal with the consequences of what would happen.

Speaker 2 So it made him a very, very original and unsettling, and

Speaker 2 sometimes at the risk of being unentertaining, but he was not afraid of those consequences. In fact, that's exactly what he was trying to engender.

Speaker 5 I will not say it.

Speaker 2 This has been a

Speaker 5 very hard week for me.

Speaker 5 Why? I don't, you know, I'm not trying to be funny right now. This is true.

Speaker 5 Because of last week's show,

Speaker 5 my job

Speaker 5 at taxi is in jeopardy.

Speaker 5 My agent and myself are finding it very hard to convince other people in the show business community to hire me for other television shows.

Speaker 5 And you laughing at this.

Speaker 5 I think that your laughing at it is pretty tasteless.

Speaker 3 Another aspect of

Speaker 3 your chapter on working for Fridays and being in a comedy writer's room and having the sort of different personalities and also back to the sense of the transgressive, sort of subversive edge that you were going for on Fridays.

Speaker 3 I mean, you're quite frank that a lot of this was fueled by drugs, just like the work schedule itself and cocaine in particular.

Speaker 3 And I'm just wondering, like, what your thoughts are on the connection between drugs and American comedy, for better or worse.

Speaker 2 Well, I would go one step further and say the connection between drugs and American literature, you know, or literature in general.

Speaker 2 I think that, you know, when you look at the beat generation or you look at different, you know, the Hemingway generation, you know, there was always something, some substance

Speaker 2 fueling

Speaker 2

their sensibility and their muse. So I don't think it was that unusual.

That happened to be the drug of choice at that time.

Speaker 2 On both Saturday Night Live, and we know what happened to John Belushi, and on Fridays, the schedule that was worked out was so inhumane.

Speaker 2 We had to be writing all the time. And as soon as the show was over, we had to go back and come up with sketches for the next week.

Speaker 2

And if you couldn't produce, you would fall by the wayside and be fired. So there was pressure.

And to the point that we used to get the cocaine, grams of cocaine, delivered to our desks like pizza.

Speaker 2 And so that we were always fueled by it. And at first,

Speaker 2 it was an amazing thing, you know, and it really did fuel the confidence, fuel the

Speaker 2 bravery to try things and not be afraid of the consequences in that Andy Calpin type of way, who was, by the way, the most straight person you could ever imagine.

Speaker 2 But we used cocaine to reach that level of trying stuff that was experimental and to see what would happen and not be worried about failing.

Speaker 2 In fact, kind of almost looking forward to failing because that was sort of a cool thing to do.

Speaker 2 But what happened was eventually for a lot of people, and this didn't happen to me and I was lucky because I was certainly doing a lot of cocaine.

Speaker 2 But at some point, some people reached the point where they were becoming very addicted to it, where they moved on to even crack and basically ruin their lives and kind of ruin their careers.

Speaker 2

And that was the end for them. They kind of spun out.

of TV altogether and never really worked again. And other people sort of got their shit together and and were able to kind of stop like I did.

Speaker 2 I kind of just stopped cold turkey at a certain point and was able to do that because it went from being a confidence builder to destroying your personality.

Speaker 2 We went from before the show, we would spoon each other like the group of writers, like we had such camaraderie around it to us

Speaker 2 eventually just taking our Coke. going into our rooms, closing the door, and just doing lines by ourself and not wanting to share it with anybody, you know, because it was so precious.

Speaker 2 So the change of personality was also very distinctive on the show.

Speaker 3 And also sort of like the confidence boost, you feel like, God, you feel like everything you're saying is the smartest, funniest thing. But then like,

Speaker 3 but then like not being able to have that feeling without cocaine is like, that's a very dangerous thing.

Speaker 2 Right. But in some ways, I think,

Speaker 2 and this, I think, I would say this is true of acid also, by the way.

Speaker 2 In some ways, those things showed you what was possible you know uh with without those drugs and you know you needed to do those drugs to some degree in order to experience what that was like because maybe you would not have attained that level without them and then once you were able to let go of those drugs you still knew what it was like to attain that level and you could possibly try to attain it without the help of outside substances well uh one of the uh the best um uh stories you relate from your uh time working on Fridays was the incident where you were tackled by the Secret Service.

Speaker 3 Could you illustrate for our listeners here the sequence of events that led up to you being tackled by two Secret Service agents?

Speaker 2 Well, America was in a very weird place at that time. And

Speaker 2 Carter, I think Carter was in the process of about to lose the election, and Reagan was about to win. And

Speaker 2 Larry Flint had been, there had been an assassination attempt on his life, and

Speaker 2

it didn't kill him, but it handicapped him and he was relegated to a wheelchair. And we had weird celebrities come to the show to hang out.

And one night, Larry Flint and his wife, Althea,

Speaker 2 who were very drugged up on whatever, and their entourage, which included Ruth Carter Stapleton, Jimmy Carter's sister, who was an evangelist, they came together to the show and hung out in the green room.

Speaker 2 And Larry Flint at that time was, he had gone, he had been through a number, almost like Bob Dylan, he had decided to become born-again Christian. Now, was it real or not?

Speaker 2 I don't know, but Ruth Carter-Stapleton became his spiritual advisor. So they all kind of rolled into the green room together.

Speaker 2 They had Hell's Angels with them for security, Ruth Carter-Stapleton, who was like a little old lady from Georgia.

Speaker 2 You had Larry Flint and Althea, who seemed like they were really, you know, kind of stoned already. And they were hanging out there.

Speaker 2

And word came down to the sub-basement where the writers were that Larry Flint wanted a joint. And I immediately volunteered and I rolled up a joint.

And I wanted, the show was about to start.

Speaker 2

And I raced up the stairs and across to the stage and into the green room. And I'm racing towards the green room as fast as I can.

And suddenly I'm taken by two guys and I'm taken down on the ground.

Speaker 2

And they're on top of me. Like, what do you think you're doing? And these were Secret Service guys because of Ruth Carter Stapleton.

And

Speaker 2 I said, I have a joint for the president's sister.

Speaker 2

And they will, and that worked, you know. They were like, oh, okay.

Okay. And they helped me up and they let me in.

Speaker 2 And I walked into this really weird room filled with all these, you know, disparate people and gave the joint to Larry Flint. Well,

Speaker 3 your next sort of stop on your career, and I wasn't aware of this, is that you were a writer for the Arsinio Hall show.

Speaker 3 And Arsinio was like one of the like, was he like the first black late night host on American television?

Speaker 2 Most definitely. Yeah.

Speaker 2 He was a black star when there were no black stars really on TV, or very few.

Speaker 3 And I think the interesting part of that chapter is like you talk about

Speaker 3 just sort of the experience of being a minority in an organization, like

Speaker 3 in a mostly black writing staff and production team.

Speaker 3 What did that experience teach you?

Speaker 3 And also, did it give you any insight into like, do you think that there is like something markedly different in Black American humor and white American humor and like, and how black and white people relate to humor?

Speaker 3 Like, what did that experience mean to you?

Speaker 2 Well, I was struck by many different layers of the black experience working on Arsenio. I think that, you know,

Speaker 2

the background, the place that people, that black people came from was very very different than the place that Jewish people came from. But there was a lot of overlap.

You know, that was one thing.

Speaker 2 I mean, I think the idea of being the minority in a group, which Black people, of course, always experience in so many situations in the society.

Speaker 2 But as a white person in America, being a minority is rare.

Speaker 2 I also did this show, Larry Charles D'Anterest World of Comedy, where I went to a couple of African countries where I was basically me and my staff, my crew, my small crew, were the only white people that we saw the entire country.

Speaker 2 There is a kind of an educational, inadvertent educational experience to that that I would advise everyone to try to avail themselves of because it really gives you the perspective of what that's like.

Speaker 2 On Arsineo, you would see all the different stratas.

Speaker 2 of black society because you would see that regional differences, that shade, you know, skin shade differences, educational differences, all the different intricacies of any society were true in the black society.

Speaker 2

We tend to generalize about black society. Black people want this, black people want that, black people do this.

And that was simply not the case.

Speaker 2 Once you got deep inside the black community, you realized there was as much, you know, a diversity within the black community as any other community. And that was the main thing that I learned.

Speaker 2 and of course their humor was was based on the same sort of frustrations and angers and fears as as the white community and and i thought that also was very um enlightening uh to know that and this is something i tried to also bring out on dangerous comedy which was that we all are really laughing and experiencing the same things to a large degree And if we recognize that more, it might sort of chill out some of the tensions that exist in the in the country, in the world.

Speaker 4 Did you notice,

Speaker 4 this is something I've thought about a bit

Speaker 4 because like Chicago is, there isn't like total racial parity demographic-wise, but a lot of neighborhoods are there, there's an equal amount of white people and black people.

Speaker 4 My neighborhood was like kind of like that for weird reasons because the, you know, you Chicago is there. But I feel like there's an under discussed current of like irony in black comedy.

Speaker 4 Like not to generalize of there being like, you know, a monolithic type of black humor, but I think like black comedians shepherd the concept of irony, at least as far as like audiences could understand it.

Speaker 4 probably more than like anyone since like the 1970s or 80s.

Speaker 2 Well, I think you're talking, you know, again, again, if you go back to the origins of black comedy, you think about Red Fox, who most people know, maybe from San Francisco.

Speaker 2 But what he was really most known for before that were putting out these incredibly filthy, dirty party records. And there was a tradition.

Speaker 2 It was almost black comedy was like an underground tradition for a long time. And then Richard Pryor was very influenced by that.

Speaker 2 And he came along and he brought that very underground sensibility, that hardcore sensibility to the mainstream. And he really single-handedly changed comedy across the board.

Speaker 2 Racially, you know, it didn't matter. I mean, everyone was influenced by Richard Pryor.

Speaker 2 And still to this day, you can see the influence of Richard Pryor in the same way that you can see the influence of George Carlin.

Speaker 2 To me, they're the two people that basically affected comedy more than anybody.

Speaker 2 You know, you could talk about Lenny Bruce and you could talk about Steve Martin. There's a lot of of people, but those two guys really,

Speaker 2 because George Carlin was doing very kind of, it was very clever and funny, but it was very safe comedy at first, doing the hippy-dippy weatherman. And he made that turn.

Speaker 2 He discovered drugs, made that turn and started doing the seven words that you can't say on television. And Richard Pryor started bringing that underground sensibility where black humor had resided.

Speaker 2 and he brought it to the mainstream and found out that the audience, all audiences, really were craving that without even realizing they wanted it.

Speaker 2 And it was an explosion when he came out with his concert movie.

Speaker 4 We've talked about Red Fox before on this show.

Speaker 4 You know, you brought him up as someone who was enormously influential to, you know, Pryor, who's probably the single most influential comedian of like the last 60 or 70 years.

Speaker 4 Red Fox is, you know, the way that like

Speaker 4 Marlon Brando was the first like on-screen, on-screen actor, you know, to not elocute like this.

Speaker 4 He changed acting by speaking in a more natural way that conveyed emotions. That's sort of how I would equate Red Fox.

Speaker 2 I would agree with that.

Speaker 4 It's not that like comedy sucked until him, but there was no one,

Speaker 4 there was like a naturalistic way that he delivered jokes that like no one was really doing until him.

Speaker 3 There were jokes that were like gags, but like Red Fox was like, and like that, that sort of underground black comic tradition that you're talking about.

Speaker 3 They're the ones who like were able to to sort of like to render with language the kind of shared obscenity of being alive and the experience of the shared obscenity of life and like you know all its uh bodily functions and glory and sex and all that well that's where lenny bruce comes in also i think you know you talk i i agree with you a hundred percent i mean i think red fox was like having a conversation with the audience, you know, rather than like

Speaker 2 he was trying to tear down that wall between the performer and the audience and his performance style.

Speaker 2 And I think for most comedians, most white comedians, most conventional comedians, they wanted that wall to be up.

Speaker 2 They were doing the typical routines, whether they were, you know, set up a punchline or whether they were monologues. It was like

Speaker 2

they were not really interacting. except saying what they were going to say and getting a laugh.

It was a very sort of binary kind of relationship.

Speaker 2 And whereas Red Fox really tore down all those walls and Lenny Bruce did too, and just was like sort of interacting with the audience.

Speaker 2 I worked with Richard Belzer years later, obviously, and he had a similar kind of reaction with the interaction with the audience.

Speaker 2 He wasn't really so worried about having bits.

Speaker 2

He was more into like creating a moment. in every show that he did.

And Red Fox had that same quality also.

Speaker 2 And that's why his albums were all live albums because they were recorded at performances where it was only like, this is the only time you're going to get this performance for Red Fox, the next time it'll be different.

Speaker 2 And it's like, even like the Grateful Dead, you know, it's like you didn't know what they were going to do from show to show.

Speaker 2 And the great comedians, I think, also were trying to mix it up and keep it surprising. So you weren't just going to see them do their tried and true routines.

Speaker 3 Larry, like another big part of this memoir is, I think it's a fairly,

Speaker 3 it's a very honest look at what professional creative friendships and working relationships are like and the sort of the highs and lows of professional and creative collaborations, particularly in comedy.

Speaker 3 And just like, you know, you and Larry David, like he figures very largely in your life and this book through, you know, Seinfeld and then Curb Your Enthusiasm. What is it?

Speaker 3 What was it about Larry David and your sensibilities? Was it like,

Speaker 3 what were the shared sensibilities and what were the differences that like that made for your creative collaborations to be so fruitful?

Speaker 2

Well, I mean, meeting him when I did, you know, again, these were very sort of fortunate set of events. I was like 22, 23.

He was like nine, 10 years older than me.

Speaker 2 So he was already a man and I was still a kid. And really, I often say he was like the most influential person in my adult life.

Speaker 2 I mean, going back to Fridays, he really taught me how to be a man in a a lot of ways. I mean, he taught me about discipline, about craft, you know, about integrity.

Speaker 2 Those are three things that he really had already that I didn't even consider.

Speaker 2 They weren't on my agenda at all. And I realized how important they were and how important they were to what I was doing also as a writer.

Speaker 2

So that right off the bat became very important. Plus, he was from the same neighborhood as we talked about.

So I immediately knew the dynamic. You know, I understood the dynamic.

Speaker 2 So there was a lot there that we were in sync about right away. We were laughing at the same things and we understood the language.

Speaker 2

We had a kind of a Brooklyn, a South Brooklyn, Brighton Beach, Sheepshead Bay language that we shared. And that was very important also.

But in other distinctive ways, I mean,

Speaker 2 the books that influenced him were different than the books that influenced me. His big influence.

Speaker 3 Yeah, no, I was shocked by this, that one of Larry David's favorite books and one of his like sort of lifelong guiding stars and inspiration is Ayn Rand's The Fountainhead.

Speaker 3 And he sees in himself Howard Rourke as this uncompromising figure.

Speaker 2 And you can kind of, you know, as crazy, as crazy as that sounds, you can see it. You know, he is of, he is like a Jewish, Brooklyn Jewish Howard Rourke, you know?

Speaker 3 Well, I mean, you see that on Curb Your Enthusiasm is like so much of

Speaker 3 the episodes are like his refusal to back down from what he thinks is a point of ethical or moral pride. That's right.

Speaker 2 And even in this, when we did Seinfeld, he would fight, and I would back him up always.

Speaker 2 I was always behind him on these arguments, but he would fight with the network and with the production company every week on every read-through.

Speaker 2 He would not relent. His integrity was unassailable.

Speaker 2 He would not compromise as much as he was begged to compromise on certain things about the show, which would have ruined the show.

Speaker 2 You wouldn't be talking about Seinfeld today if he had done those things. He held firm and challenged them like Howard Rourke blows up the building.

Speaker 2 He challenged them to blow up the show.

Speaker 2

He didn't care. He said, go ahead, cancel us.

I would rather you cancel us than do that. And so he always had that sense of...

Speaker 2 just almost insane integrity that no one else really had and really is the secret to some degree to his success and something that I absolutely

Speaker 2 processed and absorbed very closely.

Speaker 3 My favorite part from the Curb Your Enthusiasm chapters that I'm hoping you could share with our listeners is the story about what happened between you and Mel Brooks's assistant.

Speaker 2 So weird. Very weird story, yeah.

Speaker 3 I mean, because this is an example of like life imitating art. I mean, this is sounds like, I mean, it began with an episode of Curb Your Enthusiasm about Mel Brooks' assistant.

Speaker 3 And then you had to live out a real life Curb Your Enthusiasm episode with Mel Brooks' assistant.

Speaker 2

First of all, I had the thrill. I mean, I was so thrilled of getting the chance to direct Mel Brooks, you know, and I directed him for an entire season.

And we got very, very close.

Speaker 2

And I felt great kinship. And he was also a very paternal influence on me.

He was such a sweet, loving, generous person, you know.

Speaker 2 And so we did an episode in which his assistant is gay and she has her gay lover. And Larry has this awkward encounter with her when he goes to see Mel and kind of insults her.

Speaker 2 And she tells her girlfriend who threatens Larry. And

Speaker 2

at the end of the season, the season was done. The shows were on.

It was a big success, actually.

Speaker 2 And I got a call from Mel saying, you have to call my assistant, my real assistant, and apologize to her. And I'm like, why? And he's like,

Speaker 2

well, she is a, she's Filipino. She's very Catholic.

And

Speaker 2 she was very offended by the way she was portrayed on the show.

Speaker 2

And I was like, well, you know, we didn't even know anything about your assistant. We made that character up and it had nothing to do with your assistant at all.

It just happened.

Speaker 2 to be the assistant on the show for a storyline.

Speaker 2 And he's like, please, I'm begging you, call my assistant i can't afford to lose this assistant she's the best assistant i ever had call the assistant and apologize and i love mel and i thought what the hell we're apologizing that's what curb is all about is apologizing so we i i called her and i said look i'm very sorry if you were offended there was nothing meant by it blah blah blah and she actually said to me I do not accept your apology.

Speaker 2 And

Speaker 2 which I don't know if that's ever happened to me. I know.

Speaker 3 I'm like, I mean, what do you even do in that situation?

Speaker 3 I've never had an apology not accepted.

Speaker 2 Yeah.

Speaker 2 I think you have to have a duel. Yeah.

Speaker 2

I was at my wit's end. It's like, now what do I do? I tried to kind of talk her off the ledge.

I couldn't do it. She said her entire family, she had

Speaker 2 the show had shamed her entire family. And I was like, I kept apologizing, but she literally would not accept the apology and kind of hung up abruptly,

Speaker 2

still in anger. And I thought I'd be able to kind of bypass Larry on this one and not have to go to him.

I thought I could take care of it myself and I couldn't.

Speaker 2

So I had to go to Larry and I said to Larry, look, this is what happened. The assistant is offended, Mel Brooks, blah, blah, blah.

And he said, oh, don't. He considered himself to be the

Speaker 2

prime apologizer. There was nobody better at apologizing than him.

So he said, I'll take care of it. And he called her and she wouldn't accept his apology.

And so she wound up being offended.

Speaker 2

I guess Mel was able to kind of keep her for a while. I don't know.

Maybe she's still his assistant for all I know. But

Speaker 2 we could not get her to accept the apology.

Speaker 3 Well, as I said, like,

Speaker 3 the book deals a lot with professional creative relationships. And what I liked about it is I think you showed that in each of these relationships, there is a credit and a debit.

Speaker 3 Like often the things that you that lead to great,

Speaker 3 you know, productive, great creative output in comedy can debit away from personal relationships. And there can be a cost that has to be paid here.

Speaker 3 And I'm thinking about this in light of the way your relationship with Sasha Baron Cohen comes off in this book, because like you collaborated with him on three films, like Borat probably being, you know, like one of the most successful, like one of the most memorable comedies.

Speaker 3 But you and Sasha Cohen, over the course of your working relationship, like that, the debit started to grow. And I'm just wondering, like,

Speaker 3 how you regard, because like, you know, you don't portray any of these people as villains, but I think you're very honest about like the difficulties, especially in comedic creative relationships.

Speaker 2 Well, also, my own failures as well. I mean, I tried, I felt that I could be honest about what I observed in them as long as I was honest about what was going on with me as well.

Speaker 2 And

Speaker 2 I take my responsibility in that as much as anything um but with sasha you know i i i loved sasha really and i felt as close to sasha as i felt to anybody creatively and in the situation that we were in on borat it really was kind of like you know again the samurai idea of life and death stakes to the comedy it really was and i was prepared to to die for sasha because we were in situations where violence and you know mayhem were really always a possibility and i was prepared mentally to just step in there and and save him and protect him at any cost even at even at the cost of my own safety so we couldn't have been any closer and that vibe really comes through the movie i mean the exhilaration of feeling those kind of feelings you feel that in the movie it breaks through the screen to a large degree and um and of course success breeds camaraderie as well you know by the time we got to bruno it the fact that it was a such a that it was a flamboyantly gay character changed every interaction we had with the world everybody felt instead of being patient with a kazakhstani which they knew nothing about even though he was a rapist and an anti-semi and incestuous and all these things

Speaker 2 people were still patient with him you know and that kind of allowed the scenes to unfurl the way they did in that funny way On Bruno, it was much more difficult because he was just a flamboyantly gay character.

Speaker 2 People felt immediately hostile to him, immediately felt okay getting violent with him and jostling him and slapping him and threatening him. And there were guns involved.

Speaker 2 And it got much more intense.

Speaker 2 And it led to more conflict with us as well.

Speaker 2 the direction of the story, how that story should be told.

Speaker 2 What was I thought was a a more radical movie in a very good way because it did show a dark, hateful version of America that I thought was really unique for a comedy.

Speaker 2 And it's also super funny, but it's amazing how almost everybody in the world has seen Borat. But when I go around the world, so many of those same people have never, ever seen Bruno.

Speaker 2

And I think the reason is because it was this gay character. By the time he got to the dictator, Sasha's whole world had changed, really.

He had become a gigantic star.

Speaker 2 He had been married and had a couple of kids by then. And he had started surrounding himself with much more of a

Speaker 2

show business entourage. And in doing so, I think, and in doing a scripted movie, I think he kind of lost the killer instinct that he had.

on Bruno and Borat. And now he's playing a role.

Speaker 2 And he had to learn his lines and he had to practice the accent.

Speaker 2 With Borat and Bruno, he really had just absorbed and incorporated those characters inside of him so that he knew what Borat, what Borat's underwear should be like and his socks and what he carried in his pocket.

Speaker 2 But with the dictator, Aladin, he never really

Speaker 2 had time,

Speaker 2 but also never really spent the time.

Speaker 2 to understand that character and instead was getting very distracted by all the miscellaneous things that that you have to take care of in a movie that weren't nearly as important as getting his character together, which was the key to the success of that movie.

Speaker 2 He'd be worried about the flag color or, you know, the uniform and things like that instead of working on the character. And it was very hard to bring him back to that place where to focus.

Speaker 2 And he also started to rely on a lot of

Speaker 2 outside influences who gave him very contradictory advice and not the kind of advice that he needed to make the movie as great as it could be, I felt.

Speaker 2 And he just threw a lot of people at every problem and often purposely created conflict in every situation. And all of this to me was distraction from making a great movie.

Speaker 2 And it was very disheartening to see that process take place.

Speaker 4 I know you're obviously like not dumping on the guy.

Speaker 4 And it's you can have like an incredibly complex relationship when you make a lot of things with somebody and they, you know, there's this, there's a schism, you know, either slowly or very rapidly.

Speaker 4 But what you describe, I mean, it sounds like it sounds like the worst whiplash someone like that could get. I was a huge fan of the LEG show, and I actually saw a boret with my mom.

Speaker 4 She's coming up a lot here.

Speaker 2 But

Speaker 4 it's one of the funniest movies I've ever seen.

Speaker 4 But the thing I always felt, especially

Speaker 4 with a lot of the board performances that were on the LEG show, but especially with the movie, was how difficult it must have been for him to sort of zero out everyone while also being able to

Speaker 4

evince some sort of usable material from their reactions. It must have required, you know, an enormous amount of focus.

and also a very weird type of solitary confidence.

Speaker 4 But then just becoming a normal celebrity, that's the, your brain is going in the complete opposite direction.

Speaker 2 Yeah, I, you know, you mentioned Marlon Brando before. And to me,

Speaker 2 since Marlon Brando,

Speaker 2 Sasha actually, in a way like Marlon Brando, introduced a new form of acting.

Speaker 2 To me, Sasha should have won an Oscar for Borat because Nobody has done a performance like Borat where he is Borat 16 hours a day, six days a week, without breaking in front of real people and creating an illusion that is so real that people didn't question who it was.

Speaker 2

That is the ultimate illusion of acting. And he didn't get credit for that really, I think.

I mean, people loved him and loved the movie, but as an acting exercise, that was unprecedented.

Speaker 2 And I think over a course of time, rather than, you know, kind of honing in on that the way Andy Kaufman, I think, would have if he had lived, I think that Sasha wanted, he didn't want the pressure anymore.

Speaker 2 He didn't want to be frightened every time he went into a scene that he was going to be hurt. I don't think he wanted to go through that again and refuse to do a Borat sequel at that time.

Speaker 2 You know, I think that he wanted a kind of an easier way to make a living, you know, and I think being a Hollywood star was a lot easier than being Sasha, the guy who did Borat.

Speaker 2 And I think he moved in that direction. And I think artistically,

Speaker 2 that hurt him and also compromised his muse, which had been very sharp and singular and then suddenly was not quite as special.

Speaker 2 He took the edge off his own. his own comedy sensibility.

Speaker 3 Well, we talked about sort of the ephemeral nature of comedy and like how sort of transitory it is, like what a low shelf life it has for even

Speaker 3 the best comedic material. And then also throughout your career,

Speaker 3 your willingness to push the boundaries and to be offensive, to be subversive,

Speaker 3 to portray things that shouldn't be funny, like to be willing to risk that. And I think part of that is the instability.

Speaker 3 I'm just speaking for myself here of having been a fan of a lot of your work and a lot of the collaborators that you've worked with.

Speaker 3 And in no way am I asking you to like condemn them or apologize for them, but it has been weird for me personally to

Speaker 3 see now like particularly someone like Bill Maher, who is someone I used to really love, but now who I think is using his comedy in a way that I do genuinely find offensive.

Speaker 3 And like not only not funny, but I'm sort of like, now I'm have to wear the shoes of being like, I'm actually offended by a comedian.

Speaker 3 And like, you know, in light of his, you know, like ongoing support for what Israel is doing to Palestine right now, Jerry Seinfeld, I could throw in there too.

Speaker 3 What do you make of that instability?

Speaker 2 Sasha, too, by the way. Yeah, yeah, yeah.

Speaker 3 So

Speaker 3 the issue of Zionism in comedy and that instability there where now I have to feel uncomfortable for liking a comedian.

Speaker 2 Well, I'm very disappointed.

Speaker 2 I really love all three of those guys in a very... profound way and I'm very grateful to all three of those guys.

Speaker 2 But I am also extremely, when you talk about Israel and Palestine, I am extremely disappointed that they have been so blind to the realities of that situation.

Speaker 2 I have been to Palestine three times, once with Sasha. And,

Speaker 2 you know,

Speaker 2 I'm surprised at how their

Speaker 2 the take that they have come up with on that situation. And

Speaker 2 going to Palestine and meeting the people in Palestine, as I did in Dangerous Comedy and meeting comedians from Palestine,

Speaker 2 it was clear that these people are victims, they're prisoners,

Speaker 2 they just want peace, they're not warlike people, they're destitute, they are the underdogs, and you would think comedians would relate to that, but instead, this kind of blind support for this Israeli genocide, I mean, it

Speaker 2 because I don't know what else to call it.

Speaker 2 People argue about that word, which seems absurd to me also. It's like, well, call it whatever you want.

Speaker 2 There's tens of thousands, if not hundreds of thousands of people being murdered needlessly, children starving, maimed, killed. You know, it's insane.

Speaker 2 I mean, how you could justify that and how the American media and the American system, based on the justice of the American government, justifies it.

Speaker 2

But when you see comedians supporting that, it's very disheartening. It's very perplexing and confusing and disappointing.

And it is a big area of separation between me and those three people is their

Speaker 2 casual support for a country like Israel in the midst of what's going on right now. So

Speaker 2 I don't know how to explain it.

Speaker 2

Bill has always been that way. Sasha has always been that way.

But even now, when things have kind of amped up so much in that part of the world, they have not really veered from that stance.

Speaker 2 And that surprises me.

Speaker 3 Well, I mean, like Bill Maher, especially, because like you guys did Religious, like a whole documentary that's sort of puncturing the absurdities of organized religious faith and religious belief and all the violence it causes.

Speaker 3

So like Bill Maher's thing is weird because he's like, I'm 100% an atheist. All religions are stupid.

I don't believe in God, but he did give Israel to the Jews. And that's 100% true.

Speaker 2 He's cited.

Speaker 4

I've seen him cite the Bible in those arguments. And it's like, okay, now it's, now it should dictate policy.

And I mean, Sasha too.

Speaker 4 Like, I before he became more outspoken with the Zionism stuff in the last few years, the thing that really surprised me was he was a big, you know, we have to stop anti-Semitism.

Speaker 4 You know, there are tropes everywhere. And I thought,

Speaker 4 would you apply any of that rubric to your own work?

Speaker 4 Would you apply this incredibly like hectoring, punitive language policing towards, you know, what your work might say about like Muslims or gay people for that matter. It just,

Speaker 4 in both cases, it,

Speaker 4 like, and I, I, I don't think that, like, Borat is like an invective against Muslims, but it's just in both cases, it's two people completely going against.

Speaker 4 what they've done their entire career in some sense.

Speaker 2

Yeah, I'm very, I'm very open. I don't believe that anything is off limits.

I believe that any subject can be a subject for comedy if you find the right angle.

Speaker 2 And I'm happy to make fun of everybody and everything

Speaker 2 if you can find the right angle for it.

Speaker 2 This kind of transcends that to some degree.

Speaker 2 You know, it almost

Speaker 2 defies logic. in my opinion, you know, to see the suffering that's going on and

Speaker 2 just ignore the causes of it and support the oppressors in that situation just perplexes me.

Speaker 2 I can't really explain it. And that's one of the reasons, by the way, that I did the Netflix show, the Larry Charles Deidris World of Comedy, was to show that these places where we are

Speaker 2 militarily destroying these countries and destroying lives permanently,

Speaker 2

you know, here are the people that we are doing this to. Look at these people.

They're just like you. What would you do in this situation?

Speaker 2 And I had hoped that it would cause more sort of dialogue about that stuff, but it really didn't.

Speaker 2 And instead, a lot of people just retreated to this pro-Israeli stance, this pro-Zionist stance, and allowed that to sort of

Speaker 2 be there. They just took a rigidity behind that and just have not wavered from the beginning of

Speaker 2 this particular period, which of course the the the period the historical period is goes back way before october 7th you know and um but but the propaganda has been so effective that you when you're a kid in brooklyn like i was going to hebrew school there was no doubt that israel was god's gift to the jews you know you believe that you know and it took It took a while, like around my time in my bar mitzvah, for me to start questioning all this supposed wisdom about it and realizing it was all kind of bullshit.

Speaker 2

And, but for a lot of people, they still buy into that. They buy into the propaganda.

But maybe we shouldn't be surprised because they buy into the propaganda about America too, you know? Yeah.

Speaker 3 I mean, I don't know, like, and going back to like comedy being like,

Speaker 3 how does one make sense of the most sickening and horrifying things that they're aware of in their own lives or in the world?

Speaker 3 And like for me, there is nothing more sickening or more horrifying than what's being done to Gaza right now.

Speaker 2 And I was trying to think about like, yes, I agree.

Speaker 3 But yet, still, still somehow, like, I still kind of have to relate to it in some sense, in a comedic sense, because, you know, comedy and tragedy are really just matters of perspective.

Speaker 3 It's like, what's comedy and what is tragedy? It's just like, well, give it a minute and I'll tell you, I don't know, depending on what happens. And I was thinking, like,

Speaker 3 I was struck by this, speaking of propaganda, this propaganda video that I saw, and this just struck me as like, you want to talk about like sick comedy or even like a Larry Charles style joke?

Speaker 3 This was a piece of propaganda produced by the Gaza Humanitarian Foundation, which is already a sick joke in and of itself because essentially it's just a firing squad.

Speaker 3 And it was this guy who was representing the Gaza Humanitarian Foundation. He's at one of these aid delivery checkpoints and he's giving his whole spiel about how everything you've heard isn't true.

Speaker 3

We've delivered millions of meals. We're helping people.

We're saving lives every day here. And at the very end of the video,

Speaker 3 you hear a machine gun fire go off.

Speaker 3 You just hear a brat of a gun being fired and i'm like how many takes of that did they do where like they still let how many how many gunshots are going off that that was the best take of that propaganda video where they're like we're definitely not killing people here and then as as the video ends you hear a machine gun go off yeah no i think that you're you're right i mean that there is an absurdist comedy to that uh and we can laugh at it you know i mean having visited iraq and having visited palestine

Speaker 2 even the people there have a sense of humor about it on some level, because again, that is one of the few survival techniques that they have available to them. Humor is one of the last bastions

Speaker 2

of defense for those people. That's the only way they get through the day is to sort of try to laugh.

But man, they are really, it is a lot of pressure. in that situation to try to laugh.

Speaker 2 You know, very hard to do. When you're seeing children, you know, being maimed, it's hard to laugh.

Speaker 2 You know, even we were talking about dead baby jokes before, you know, but it was very removed from reality when we were kids. Now it's real, you know, and it's very hard to separate it.

Speaker 4 You know, as we were talking about, like,

Speaker 4 how do you, what is the humor in this situation? And, you know, of course, it is, it's always like in the absurdities and the inherent contradictions. But it did make me think,

Speaker 4 I have, like, I've seen not only a lot of like really funny jokes and videos from people who live in Gaza, like there is, there is a guy who's like, he's like a

Speaker 4 fitness, not influencer, but he does fitness videos and he lives in Gaza. And they're like, they're like very dark

Speaker 4

a lot of the time for obvious reasons, but like... Really, he just has like an innate sense of like timing and absurdity.