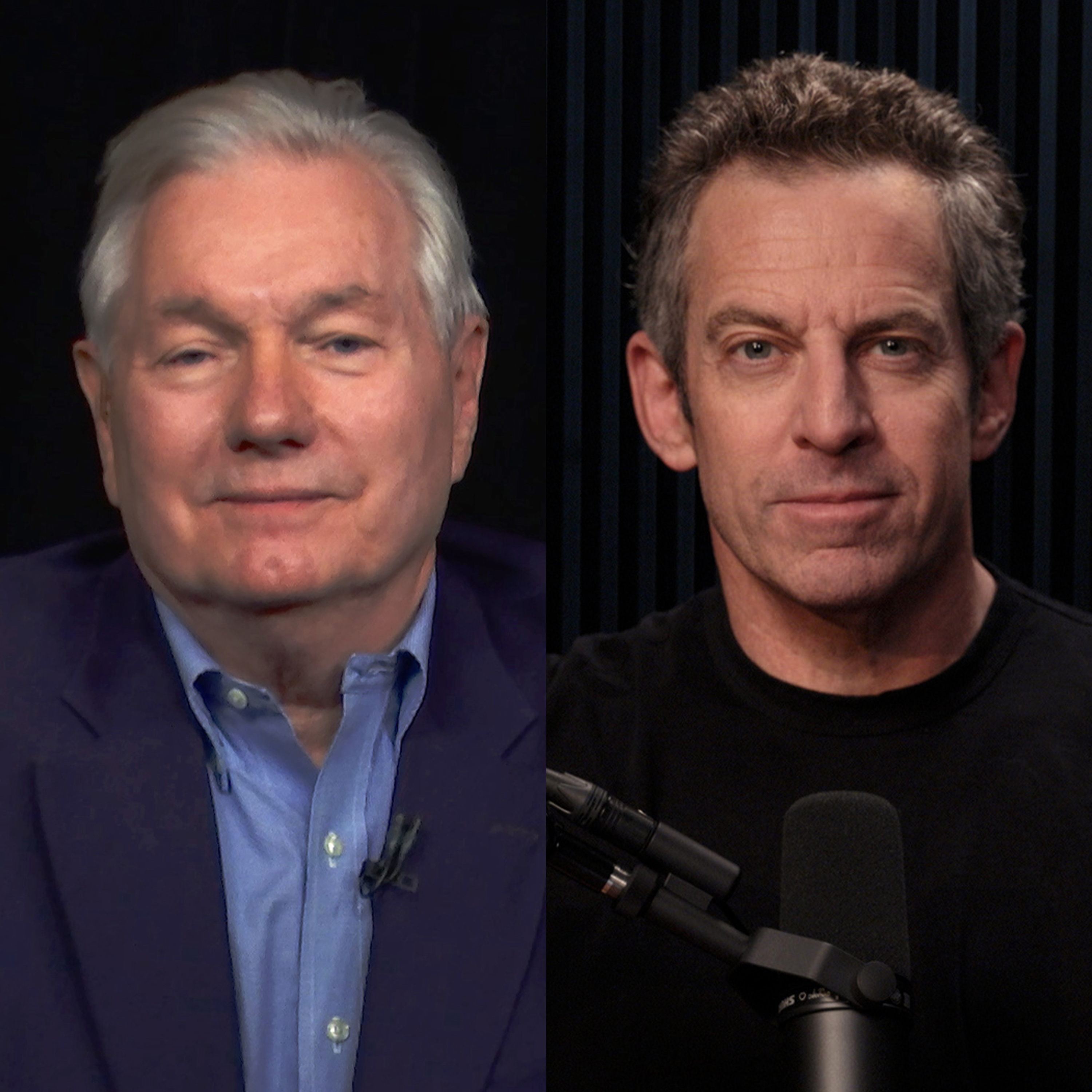

#436 — A Crisis of Trust

Sam Harris speaks with Michael Osterholm about his new book, The Big One: How We Must Prepare for Future Deadly Pandemics. They discuss the lessons learned from the COVID-19 pandemic, the major mistakes made in the public health response—including lockdowns, school closures, and border policies—the science of airborne versus droplet transmission, the promise and controversy of mRNA vaccines, the reality of vaccine adverse events, the politicization of vaccine hesitancy, and the erosion of scientific institutions like the CDC and HHS under the Trump administration. Looking forward, they explore the characteristics of a future, more deadly pandemic—what Osterholm calls “The Big One”—and what we should be doing to prepare for it.

If the Making Sense podcast logo in your player is BLACK, you can SUBSCRIBE to gain access to all full-length episodes at samharris.org/subscribe.

Press play and read along

Transcript

Speaker 1 Welcome to the Making Sense Podcast. This is Sam Harris.

Speaker 1 Just a note to say that if you're hearing this, you're not currently on our subscriber feed, and we'll only be hearing the first part of this conversation.

Speaker 1 In order to access full episodes of the Making Sense Podcast, you'll need to subscribe at samharris.org.

Speaker 1 We don't run ads on the podcast, and therefore it's made possible entirely through the support of our subscribers.

Speaker 2 So if you enjoy what we're doing here, please consider becoming one.

Speaker 1 I am here with Michael Osterholm. Michael, thanks for joining me.

Speaker 2 Thank you for having me.

Speaker 1 So you have written an alarming book titled The Big One, How We Must Prepare for Future Deadly Pandemics.

Speaker 1

You co-wrote that with Mark Olshaker. And we're going to get into that.

I mean, obviously,

Speaker 1 we're,

Speaker 1 I think, as a presage to your book. I mean, actually, actually, your book accomplishes much of this as well.

Speaker 1 I think we should do a bit of a post-mortem on the COVID pandemic and what we've learned or failed to learn from that experience.

Speaker 1 That was as bad as that was, that was a kind of dress rehearsal for the thing you're imagining, which would be quite a bit worse.

Speaker 1 Before we jump in, what is your scientific background and what are your responsibilities as an epidemiologist at this point?

Speaker 2 Well, I actually was fortunate enough to know when I was in seventh grade, I wanted to become a medical detective.

Speaker 2 It turned out that someone in my small Iowa farm town actually subscribed to The New Yorker.

Speaker 2 And at that time, there were a series of articles in there by Burton Roger, which were medical whodunits, basically kind of the CDC versions of these outbreaks.

Speaker 2 And when I read that, I said, this is what I want to do.

Speaker 2 So when I graduated from undergraduate, I immediately went to graduate school at the University of Minnesota in infectious disease epidemiology.

Speaker 2 And at the same time, I was employed by the Minnesota Department of Health.

Speaker 2 And so I've now been in the business 50 years, of which 25 of those years were split between the university and the State Health Department. And then 25, I've just been at the university.

Speaker 2 Throughout that time, I also have had a number of other appointments.

Speaker 2 And I think for the context of our comments today, I've had a role in every presidential administration since Ronald Reagan, having been involved with HIV AIDS back in the 1980s.

Speaker 2

And during Trump 1, I was a science envoy for the State Department, going around the world trying to help get us better prepared for a pandemic. That was in 2017, 18.

Not sure we did so well that way.

Speaker 2

And then, of course, I was on the Biden-Harris transition team. So I'm an epidemiologist by training.

Our group has been involved with many, many outbreaks of international importance.

Speaker 2 And then at the university, I started the Center for Infectious Research and Policy in 2001, the same week as 9-11.

Speaker 2 And we had already been very involved. in the area of bioterrorism.

Speaker 2 In fact, I wrote a book that was published on September 1st of 2000 that was called Living Terrors, What Our Country Needs Notice 5, the Coming Bioterrorist Catastrophe.

Speaker 2 And right after, of course, 9-11, my book, which I think I had bought 14 of the 18 copies that were sold in the year between its publication and 9-11, then became a New York Times bestseller.

Speaker 2 I ended up splitting my time between Minnesota and the Department of Health and Human Services in Washington as an advisor to then. Secretary Tommy Thompson.

Speaker 2 So I was very involved in those international activities and have really had a variety of experiences, but I've published a lot even early on on the issue of the potential for pandemics.

Speaker 2 In 2017, I published the book Deadliest Enemies, Our War Against Killer Germs, and I laid out in three chapters what a serious pandemic would look like,

Speaker 2 which I had suggested it was an influenza virus. It was obviously a coronavirus, but if you read the three chapters, you would think it was exactly what had happened throughout the course.

Speaker 2 So I continue to be obviously very engrossed in in the issue of pandemic preparedness, but it comes from a lifetime of experience with infectious diseases.

Speaker 1

Well, as you know, management has changed over at the HHS since you were there. I think we'll probably get a chance to comment on that.

But let's talk about your experience during COVID.

Speaker 1

Many of us, I think, first discovered you on Joe Rogan's podcast. You appeared fairly early in the pandemic.

And I must say,

Speaker 1 you found yourself talking to a very very different Joe Rogan than the Joe Rogan that we have with us now on these topics. What was your experience of trying to message into

Speaker 1 a very fragmented

Speaker 1 information landscape during the first months and maybe perhaps first year of COVID?

Speaker 2 Yeah.

Speaker 2 Well, first of all, we picked up on this situation in Wuhan actually on December 30th of 2019. So we were well aware of what was going on at that time.

Speaker 2 And of course, we didn't have an infectious agent at the point. But then soon

Speaker 2 after we realized it was an influenza virus, and I thought, well, this is great.

Speaker 2 We can probably control this because I'd been very involved with both SARS and MERS, two other coronavirus infections that occurred.

Speaker 2 In 2003, SARS, a severe acute respiratory syndrome disease that came out of China.

Speaker 2 was one that because I was still at the Department of Health and Human Services, I helped respond at a national level.

Speaker 2 And what we found was a virus that was not that infectious, except for a few super spreaders, but enough so that we could really control it. But it killed anywhere up to 15% of the people.

Speaker 2 And then in 2012, we had another coronavirus emerge on the Arabian Peninsula, MERS, Middle Eastern Respiratory Syndrome, a virus that originated from camels.

Speaker 2

And very much the same picture as we saw with SARS. in the sense that it wasn't that infectious, we could really control it.

But the difference was 35% of the people who developed MERS died from it.

Speaker 2 And so that was surely a warning.

Speaker 2 And in my book in 2017, when I laid out the three chapters that talked about pandemics, one of the chapters after that was on coronavirus as a harbinger of things to come.

Speaker 2

And so I kind of sensed that we could see a very different world. Well, along comes MERS and following SARS.

giving us a sense of what could be really bad.

Speaker 2 But then, of course, we saw COVID arrive and it was highly, highly infectious, unlike the other two, but it was not killing nearly as many, one and a half percent of the people, which still is a very real and large number.

Speaker 2 And so at that point, when early in the pandemic, I thought if this was a coronavirus, this is good news. We're going to be able to control it like we did SARS and MERS.

Speaker 2 Well, that went out the window quickly when we recognized that there was clearly a lot of airborne.

Speaker 2 aerosol-based transmission occurring, people not even knowing they were infectious, infecting people at long distances away from them.

Speaker 2

And on January 20th of 2020, I actually wrote a piece on our website and said, this is the next pandemic. Get on with it.

And that was not well received by many.

Speaker 2

They didn't want to believe that such a thing was going to happen. And you noted about the issue of Joe Rogan.

Actually, on March 10th of 2020, I was on Rogan.

Speaker 2 And at that time, I made a prediction that I thought we could easily see 800,000 deaths in the next 18 months in this country.

Speaker 2

And I might as well have said bad things about everybody's mother because that too was not well received. And of course, you know what happened.

In fact, 18 months later, we were at 790,000 deaths.

Speaker 2 And so I think that was the hard part was getting people early on to recognize we really were in the face of this. And it wasn't until middle March before the WHO actually declared it a pandemic.

Speaker 1 What was the resistance to acknowledging the airborne contagiousness of COVID? There's something you talk about in your book a bit. It seemed that we were very very slow to admit this.

Speaker 1 And even as we were starting to admit it, there was this emphasis on droplet spread as opposed to aerosol spread, which perhaps you can take a moment to describe the difference, but it's a very important difference from an epidemiological point of view.

Speaker 2 Well, you know, I hate to admit this, but we still have a challenge today. There's still a core group of people that don't believe that it's airborne.

Speaker 2 What we mean by airborne and droplet-related transmission is how does the virus leave your body such that it would expose others to the virus?

Speaker 2 And in the case of a respiratory infection in your lungs, in your nasal passages that then you breathe out, basically when I talk or you talk,

Speaker 2 and when we cough, we have these large droplets that actually come out of our mouth, our nose, that if you're in the front two rows of a concert or a play, you can see the actor or singer and you see these drops constantly coming out.

Speaker 2 Well, they fall to the ground, usually within six to eight feet. And so you could be in the same room with someone 20 feet away and never really be exposed if it's a droplet.

Speaker 2 And there are some diseases that are primarily droplet transmitted. However, an aerosol is that fine, fine material that's coming out of my mouth as I speak right now.

Speaker 2 And if you could test this room, you'd find my aerosol has actually infiltrated much of the room. And you'd have no idea that it's there.

Speaker 2

To give you an idea what an aerosol is like, think of walking outside and suddenly you smell cigarette smoke and 30 feet upwind from you is somebody smoking. That's an aerosol.

That's what floats.

Speaker 2 If you're in your house and a light, light comes shining through the window and you see all those particles floating in the air, that's an aerosol. They sit there.

Speaker 2 And that's what is so challenging because they can move great distances. And in fact, one of the classic outbreaks in an airborne-related mode

Speaker 2 happened right here in Minneapolis, not far from where I am right now. at the Hubert Humphrey Metrodome back when we had the Special Olympics here for the world.

Speaker 2 And on on the opening night ceremony, all of the participants, coaches, players, et cetera, marched in from the right field kind of garage or we call it, filled the infield and outfield.

Speaker 2 Well, meanwhile, there were 64,000 people in the stands. We had not had measles in this state for five, almost five years.

Speaker 2 Well, after that night, when a young boy from Argentina who stood almost on home plate, was breaking with measles, there was an outbreak that subsequently occurred over the next 10 weeks, 10 days to two weeks, with the players, coaches, etc.

Speaker 2 But in that opening night session, there was also an outbreak of people who had never had any other association with the Special Olympics except being at the opening night session.

Speaker 2 And we had not, as I said, had indigenous measles in the States. So we figured that this had to be involved.

Speaker 2 When we actually placed where these people sat that night, they all sat in the very small same section of the stadium at 400 and almost 90 feet away from the home plate and where they're near an outtake fan was located in the stadium.

Speaker 2 And it turned out that the air was coming out behind home plate, passing this young boy, and then literally traveled through the air to that outtake fan at the time where Mark Maguire on steroids couldn't hit a home run.

Speaker 2

And it basically infected everybody in that section who hadn't previously had measles or who had. not been vaccinated.

And so it just shows you how dynamic this virus can be in its movement.

Speaker 2 And that's measles, but measles and COVID viruses are very similar in how they're transmitted.

Speaker 1 So you make the point that if the barrier you have put up or the precautions you have made

Speaker 1 would not prevent you smelling someone smoking a cigarette on the other side of those barriers or precautions, it's not going to prevent the transmission of an aerosol-based respiratory virus.

Speaker 2 You know, we engage in so much hygiene theater where people wanted to feel safe. They wanted to say, if you stay six feet away from me, it'll be okay.

Speaker 2 We spent millions and millions of dollars on plexiglass shields that were supposed to protect people. They provided no protection whatsoever.

Speaker 2

And I think that's a lesson that really needs to be brought forward for future pandemics. We need much better respiratory protection.

We need better air quality.

Speaker 2 You know, when you and I drink water out of a tap, or eat in most cases our food, we assume it's pretty much safe, but we never think about the air.

Speaker 2 And in fact, that's one of the real challenges right now is for the future, how do we help protect people, trying to stay

Speaker 2 in line with their everyday life, but at the same time, keeping them from getting infected. And one way to do that would be have a much more effective type of respiratory protection mask.

Speaker 2 The one we have now is called an N95. Basically, it's one where If you think about where does a mask leak, it never leaks in the material as such, just like a swim goggles don't leak in the lens.

Speaker 2

They leak in the seal. N95s are meant to be really tight to the face.

The problem with that is if you have something that's too occlusive, meaning it's blocking air, you suffocate.

Speaker 2 So what is unique about these N95 respirators is it's a material that's made to have enough porous space for air to move readily through it, but they have an electrostatic charge built into it.

Speaker 2 So it traps all the virus if I'm breathing it out or if I'm inhaling it in.

Speaker 2 Unfortunately, those type of respirators, as we call them, are really somewhat uncomfortable to wear for long periods of time.

Speaker 2 We should have been investing during and after the pandemic and coming up with much better respiratory protection to deal with this airborne transmission issue.

Speaker 1 Yes, we're going to talk about what we would want to prepare ourselves for the next pandemic. Again, that could be quite a bit worse from COVID.

Speaker 1 I mean, one of the things we're dealing with here, I think, is a kind of a background of fundamental skepticism about this topic because it's been widely perceived that in some ways we overreacted to COVID.

Speaker 1 And we implemented things that were

Speaker 1 just dogmatically asserted to be true, which

Speaker 1 in retrospect warrants. There was a lot of confusion around what we knew and when we knew it.

Speaker 1 COVID was a moving target, and the scientific messaging around that movement was often inept.

Speaker 1 Half of our society seems to imagine that the COVID vaccines were more dangerous than COVID itself. I believe we have someone running the HHS, RFK Jr., who is

Speaker 1 a fabulist and confabulator and liar and loon to a degree that it's a little hard to exaggerate, who is one of these people.

Speaker 1 I think he seems to believe that the vaccines were, in fact, more dangerous than the illness. And we may talk about the implications of that.

Speaker 1

There's a lot of confusion here. So to be clear, I think we should say whatever we want to say about the lessons learned or not from COVID.

But in talking about what you call the big one,

Speaker 1 we are talking about something that is unambiguously awful, where the mortality rate is an order of magnitude or worse than the mortality rate of COVID.

Speaker 1 And this will be something where the bodies will, in fact, be stacking up in the streets. And it'll be completely unambiguous as to whether this is a lethal pathogen that we need to worry about.

Speaker 1 And so the first thing you have just put forward as something we really should have in hand and don't is a mask that is much easier to wear, much more comfortable to wear, perhaps one that's washable,

Speaker 1 one that people will not hesitate to wear if they needed it, and that it's at least as good as an N95 that we have today. And so who's building that?

Speaker 1 I don't know, but somebody should get to work on that given what we're about to say.

Speaker 2 You know, to add context to this, because I appreciate very much how you just laid it out. I think you were very accurate in what you had to say.

Speaker 2 But, you know, I have experienced throughout my entire career kind of bad news mic momentum. You know, when I wrote the book on bioterrorism and what anthrax could do, it ended up doing it.

Speaker 2 In 2017, when I wrote about what a pandemic could look like, that's what COVID actually became. In each of those instances, before the events happened, everybody just said, you're just a scary guy.

Speaker 2 Well, let me just be really clear about this idea of what could be the big one.

Speaker 2 And in fact, I mentioned earlier that the the coronaviruses that we have identified causing serious illness in humans, SARS, MERS, and COVID, basically what has fortunately kept those apart from their worst details are literally just something that's a temporary basis.

Speaker 2 What I mean by that is that COVID could very well have been much more seriously causing illness, but it didn't. It was 1.5% deaths.

Speaker 2 Well, it turns out that right now we've identified new coronaviruses in the wild, in animals, that have the infectiousness of what COVID was, but it has on board also the genetic packages that could kill like MERS and SARS.

Speaker 2 So, you know, I already said, you know, we've documented MERS killed 35% of the people it infected.

Speaker 2 You know, so the idea of what I'm putting forward is even if it's 7% or 10% case fatality rate, the percent of people who get sick and die is still a lot less than what MERS could present to us if it was highly infectious.

Speaker 2 So I think people cannot deny that this is in fact truly a possibility. And the fact that we've actually identified this virus in nature is really important.

Speaker 1 Remind me, is MERS more like 30% fatal?

Speaker 2 30, 35%.

Speaker 2

Yeah. Yeah.

Yeah.

Speaker 2 And again, I worked on that extensively. I was a noted

Speaker 2 an advisor of the Royal Family, the United Arab Emirates, and I was actually on the Arabian Peninsula working on that.

Speaker 2 And then when in 2015, when an individual who had been to the Middle East came back home to Seoul, Korea, they came home with MERS, not realizing that they were hospitalized in Seoul and created several hospital-based outbreaks where they had been seen and again had that very high case fatality rate.

Speaker 2 I was in Seoul helping with that outbreak investigation. So I've seen SARS and MERS up close.

Speaker 2 And I can tell you, under no conditions would I want to see either one of them develop the ability to be transmitted like COVID.

Speaker 1 So, well, perhaps we should linger on the controversy around the origins of COVID.

Speaker 1 As far as I know, the jury is still out, and it would be rational to consider a lab leak origin and a wet market origin as something on the order of a coin toss.

Speaker 1 I mean, I know people are biased in one direction or the other, but neither thesis is crazy. Is that still the state of our understanding?

Speaker 2 Yeah, and let me add context to that.

Speaker 2 You know, I was on the National Science Advisory Board for Biosecurity, the newly appointed committee in 2005 that was supposed to oversee national research at the federal government level and in other labs around the country for reasons of safety.

Speaker 2 And so, you know, I was very involved with that. In 2012, I actually was one of several people on the NSAB that raised real concerns about how some of the flu research was being conducted.

Speaker 2

So if anything, many people would call me a hawk on lab safety and the challenges about transmission. Having said that, I am completely on board with what you just said.

We're never going to know.

Speaker 2 It's a coin toss. Was it

Speaker 2 a lab leak? Was it a spillover from nature?

Speaker 2 And my whole point is get over it and move on, because what we're not doing is getting prepared for the future, which could again be either one, a lab leak or a potential spillover. And so I think

Speaker 2 as long as we keep fixated on that question, which will never provide, we'll never have an answer that will provide us any comfort as to knowing what happened, we need to prepare for the future.

Speaker 2 So

Speaker 1 in hindsight, what would you say we did wrong during COVID?

Speaker 1 And what were the most, if you could just take the top three mistakes and not make them, what would you change about our response to the pandemic?

Speaker 2 Well, all three of the examples I'm going to give you really come back to humility and communication, okay? Let me take the first one.

Speaker 2 I wrote a piece in the Washington Post in early March of 2020 saying don't do lockdowns. They'll never work.

Speaker 2 Because of the fact we were talking about something that was likely to last up two to three years. And could we really lock down for that long of a time period? And the answer was absolutely no.

Speaker 2 What about

Speaker 2 slow the curve?

Speaker 2

Well, that's where I'm going to come next. Okay.

And so what I'd proposed is we use a concept of snow days.

Speaker 2 And what that was all about was the idea that at that early part of the pandemic, we had no vaccines. We had limited drug availability.

Speaker 2 But what was the one thing we could do to keep keep people from dying is providing them good supportive medical care.

Speaker 2 And if your hospital is at 140% census where people are in the hallways and beds and parking garages, you're getting bad care and a lot of people are going to die.

Speaker 2 And so my whole purpose here was to say, you know, what method would help us here reduce that? Well, let people know what the hospital census is every day.

Speaker 2 You know, make it your hospital has a public number. You can go look it up.

Speaker 2 And if we got to 90, 95%, percent, we would ask people to voluntarily back off of public events, of maybe even schools, et cetera.

Speaker 2 And then when that number came back down, then you could begin to resume these activities. And again, we'd keep doing that day after day.

Speaker 2 That would have given us both a public awareness of what was happening and the fact that our really most important job was to keep the hospitals from being overrun.

Speaker 1 Michael, sorry to interrupt, but isn't this epiphany contingent upon understanding that it's an an airborne illness? And

Speaker 1 there was a moment there where we were wiping down our packages because we were worried about fomites.

Speaker 1 So at what point was it absolutely obvious that we were, at least to those who are willing to admit it, that this was the worst case scenario with respect to infectiousness, at what point was it obvious that this was airborne and aerosol?

Speaker 1 and that you were not going to, you were not going to lock down so successfully so as to prevent it spread?

Speaker 2 Yeah, there was a group of us early on that published information on this issue, clearly demonstrating this was airborne. So this was as early as February and March.

Speaker 2 And we were very critical at that time of the WHO and to some degree, parts of the CDC, because they were not on board with this, even though there was very significant data supporting it.

Speaker 2 So that did happen. But I think, again, coming back to why people stayed apart, whether it was airborne or whether it was droplet particles, they still did.

Speaker 2 And so one of the things I think there's a lot of

Speaker 2

revision of history going on right now with COVID. And one of those was lockdowns.

And it turns out that in March of 2020, 41 states initiated some kind of what they called lockdowns.

Speaker 2 Now, you have to understand, I don't know what a lockdown really is when you think about all the different things that were tried, but take the state of Minnesota.

Speaker 2 We technically went into a lockdown in March of 2020. Our governor issued a directive order basically telling all non-essential workers basically to stay home.

Speaker 2

The problem was 82% of our workforce was deemed as essential workers. Now, that wasn't a lockdown.

And even with that, by early June, all but one of the 41 states had eliminated those lockdowns.

Speaker 2 So people keep talking about lockdowns that lasted for months and months up to several years. That was not the case.

Speaker 2 There were surely localized activities where people people canceled events, schools were decided, but it wasn't based on a national, federal level.

Speaker 2 And I think the challenge we had was people just were fearful of being in public places, and particularly as some of these waves of the virus continued to greatly see increased cases.

Speaker 2 And so I think the challenge we have was with lockdowns was they were mischaracterized what happened. Imagine if we had done snow days over a course of six to 12 months before vaccines arrived.

Speaker 2 I think people would have been much more compliant than just feeling like I'm locked up, now I'm not.

Speaker 1 Yaka, so what other mistakes come to mind when you look at the vaccine?

Speaker 2 Number two, I think, was with the vaccine. And this is a remarkable effort, this vaccine.

Speaker 2 I know some will be critical of it, but mRNA technology was in the works for at least 15 years before the pandemic.

Speaker 1 If you'd like to continue listening to this conversation, you'll need to subscribe at samharris.org. Once you do, you'll get access to all full-length episodes of the Making Sense podcast.

Speaker 1 The Making Sense podcast is ad-free and relies entirely on listener support. And you can subscribe now at samharris.org.