OFH Throwback- Episode #24- Did Ty Cobb Kill a Guy?

See Privacy Policy at https://art19.com/privacy and California Privacy Notice at https://art19.com/privacy#do-not-sell-my-info.

Press play and read along

Transcript

Speaker 1

You want your master's degree. You know you can earn it, but life gets busy.

The packed schedule, the late nights, and then there's the unexpected. American Public University was built for all of it.

Speaker 1 With monthly starts and no set login times, APU's 40-plus flexible online master's programs are designed to move at the speed of life. You bring the fire, we'll fuel the journey.

Speaker 1 Get started today at apu.apus.edu.

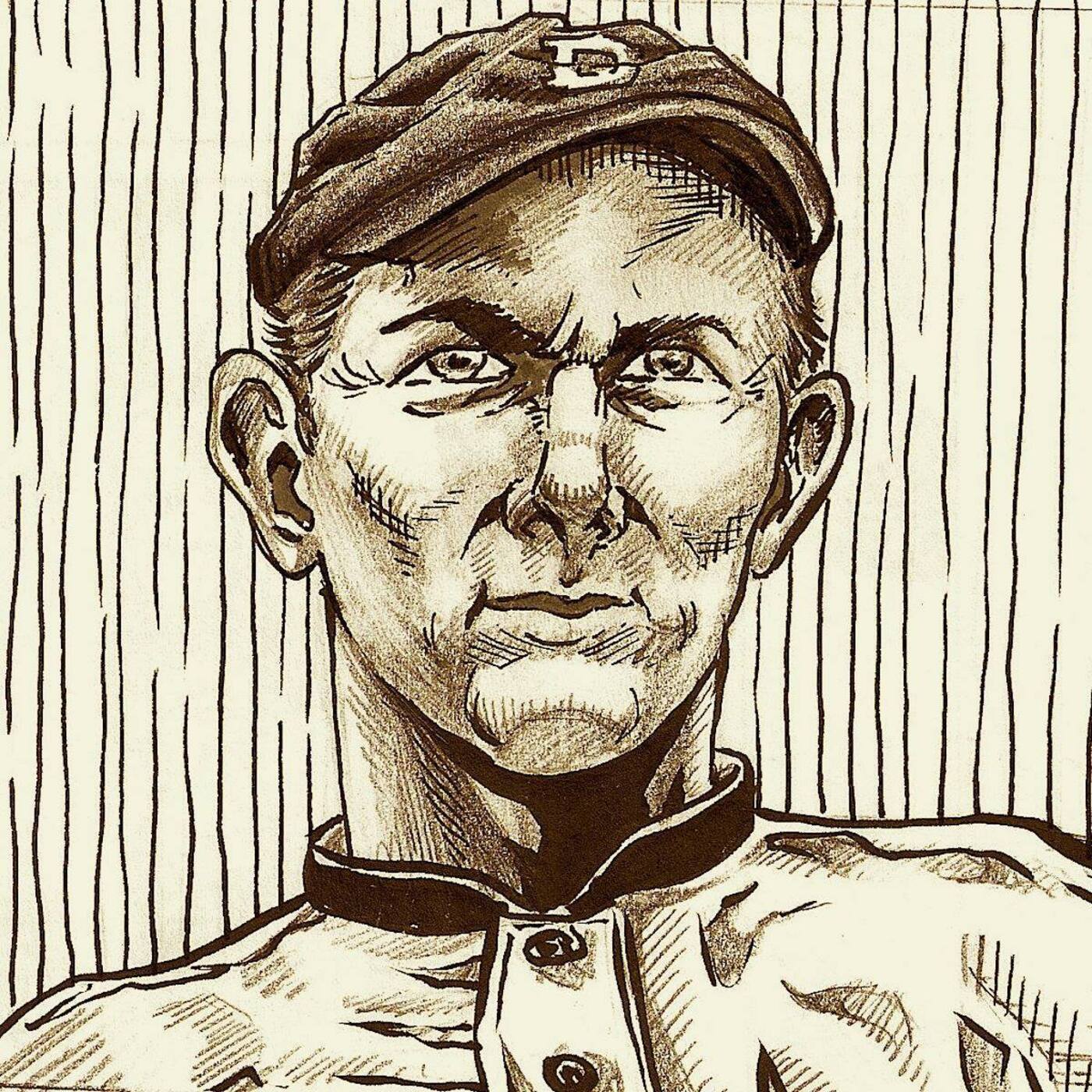

Speaker 1 Hello and welcome to this throwback episode of Our Fake History. This week I am throwing you back to season one and episode number 24, Did Ty Cobb Kill a Guy?

Speaker 1 In this episode, we explore the difficult, some might say monstrous legacy of the turn of the century baseball legend Ty Cobb.

Speaker 1 Now, this episode originally dropped on July 4th, 2016, and my, oh my, has the world changed since July 4th, 2016.

Speaker 1 I think this episode captures an interesting moment in the conversation that we were having about problematic historical figures. This episode came out before the Me Too movement.

Speaker 1 It came out before the Black Lives Matter protests of 2020.

Speaker 1 It came out before we were re-evaluating the legacies of many historical figures in the wake of all the revelations we had seen about high-profile people living in our society right now.

Speaker 1 It's been a wild nine years, I think we can all agree. With that in mind, this episode has a certain naivete about it.

Speaker 1 In this episode, you'll hear me talk about racism, hate crimes, and all sorts of violence with a certain lightness that I'm not sure I would bring to it today.

Speaker 1 In the end, though, I stand by my thesis at the heart of this episode, which is that difficult, even loathsome people need to be understood with a certain degree of nuance.

Speaker 1 I truly believe that no one is all good or all bad.

Speaker 1 Now, that doesn't mean we should let people off the hook or even forgive people for particularly nasty things that they have done over the course of their lives.

Speaker 1 But human lives are complicated and that should never be forgotten. Listening back, I found myself freshly annoyed by the sports writer Al Stump, who invented many of the worst slanders about Ty Cobb.

Speaker 1 Stump was a charlatan and an opportunist who profited off of the monstrous reputation he created for Ty Cobb.

Speaker 1 He has done a disservice to history because now it's harder than ever to get to the heart of who the real Ty Cobb was.

Speaker 1 If Ty Cobb ultimately deserves to be condemned by the opinion of history, it's harder to do that now because of all the superfluous fluff that was created by Al Stump.

Speaker 1 But perhaps my years making this podcast have made me especially sensitive to those who cloud the historical record. Finding truth is hard.

Speaker 1 When someone is out there actively messing with it, gah, makes it even harder.

Speaker 1 So, in the end, this episode is a scrappy document of the podcast in its first year and an interesting time capsule of a cultural conversation that has evolved quite a lot in the time since it was originally aired.

Speaker 1 My greatest hope is that this episode about one of baseball's greatest villains is interesting to people, even if they aren't all that in to baseball.

Speaker 1 I'm also hoping this throwback episode whets your appetite for our next series, which is also going to be about an American villain who might be a bit more complicated than you think.

Speaker 1 But that's all I'm going to tell you about that for now. In the meantime, please enjoy episode number 24.

Speaker 1 Did Ty Cobb Kill a Guy?

Speaker 1 in 1960. The sports writer Al Stump was commissioned by the ailing baseball great Ty Cobb to ghostwrite the player's autobiography.

Speaker 1 Cobb was battling terminal cancer and was hoping to have his book finished before the disease finally had its way.

Speaker 1 Now, Stump had initially been excited to meet the baseball legend and help him tell his life story, but according to Stump, this enthusiasm soon faded as he came to know the aging Cobb.

Speaker 1 According to Stump, the sickly Cob was an unpleasant and racist old man who was fond of menacing people with his favorite Belgian pistol.

Speaker 1 He was a Scrooge-like miser who, despite being enormously wealthy, refused to pay his electricity bill.

Speaker 1 He had alienated everyone around him and as a result, had to threaten Stump, sometimes at gunpoint, just to pal around with him.

Speaker 1 Stump told tales of being bullied by the great Ty Cobb into smuggling the old man out of hospitals so the two could carouse around taverns and casinos.

Speaker 1 Even worse, Stump claims that he was pressured to falsify things in Cobb's autobiography, whitewashing the man's somewhat nasty legacy. Stump later claimed that, quote, the first book was a cover-up.

Speaker 1

I felt very bad about it. I felt I wasn't being a good newspaper man.

End quote.

Speaker 1 After Cobb's death in 1961, Stump published an article in True magazine, supposedly to set the record straight about the, quote, real Ty Cobb.

Speaker 1 Titled, Ty Cobb's Wild 10-Month Fight to Live, the article read like a tell-all expose of the Baseball Hall of Famer.

Speaker 1 In it, Stump paints a picture of a bitter old psychopath brooding on slights both real and imagined.

Speaker 1 He also claimed that in their time together, Ty Cobb went so far as to confess to committing a murder.

Speaker 1 The story goes that in 1912, at the peak of his fame as a player for the Detroit Tigers, Cobb and his wife were accosted by three men attempting a carjacking.

Speaker 1 The men had persuaded the Cobbs to pull over to the side of the road by faking that they were having car troubles and needed assistance.

Speaker 1 When the Cobbs pulled over to investigate, they were immediately set on by the gang. Cobb, however, fought back with his usual ferocity.

Speaker 1 Before long, he had the men on the run, and now Cobb was out for vengeance.

Speaker 1 Stump wrote that Cobb chased one of his assailants into an alley, where he proceeded to go to work on him with his prized Belgian Luger.

Speaker 1 Stump quoted Cobb as saying that he used the gunsight to, quote, slash away until the man's face was faceless, end quote.

Speaker 1 And then finally, Cobb said that he, quote, left him there, not breathing, in his own rotten blood. End quote.

Speaker 1 In Stump's 1994 biography of Cobb, he would add the detail that a press report told of an unidentified body found off of Trumbull Avenue in an alley.

Speaker 1

This official document seemed to corroborate Cobb's wild story. You see, according to Stump, Ty Cobb wasn't just a hateful bigot and a cruel miser.

He was also a cold-blooded killer.

Speaker 1 And so grew the legend of Ty Cobb as a monster.

Speaker 1 From then on in, it was almost seen as irresponsible for an author to mention Ty Cobb without also mentioning that he was a truly despicable human being.

Speaker 1 But here's the thing: Al Stump was a liar.

Speaker 1 He has since been called up by other journalists, sports writers, and baseball historians who checked his work and found it to be more than a little suspicious.

Speaker 1 By all accounts, Stump exaggerated almost everything he wrote about Ty Cobb, and in some cases, he invented things out of whole cloth.

Speaker 1 Our whole image of baseball's most evil man was shaped by sports journalism's biggest fraud. So, what should we believe? Did Ty Cobb actually kill a guy? All that and more on today's Our Fake History.

Speaker 1 Episode 24. Did Ty Cobb kill a guy?

Speaker 1 Hello and welcome to Our Fake History.

Speaker 1 My name is Sebastian Major and this is the show where we look at historical myths and try and figure out what's fact, what's fiction, and what is such a good story that it simply must be told.

Speaker 1 This show is being released on July 4th, Independence Day, for all our friends down in the United States, so it seems appropriate that this week we are making our first foray into American history.

Speaker 1 And what's more American than the great game of baseball?

Speaker 1 It's been called the Great American Pastime, and there are few sports that have been as deeply tied to the American identity as the old ball game.

Speaker 1 As fans of the game can also tell you, baseball has inspired an entire industry of long-winded articles, and entire books, in fact, speculating about its unique cultural meaning.

Speaker 1 You see, baseball's a slow game that gives you lots to ponder, and as a result, baseball writers are notorious for waxing poetic about the significance of every series, every game, and every player to ever step on the field.

Speaker 1 In other words, it's a sport made for historians. But despite the fact that baseball has attracted a certain type of academic fascination, the history of baseball is rife with mythology.

Speaker 1 I honestly can't think of many other sports where mystical curses are such a part of the conversation.

Speaker 1 There's the famous Curse of the Bambino, a type of bad juju that was placed on the Boston Red Sox by Babe Ruth after he was sold to the New York Yankees in 1918.

Speaker 1 The curse was then credited for 86 years of missed World Series titles for the Boston team. Then there's also my personal favorite, The Curse of the Billy Goat.

Speaker 1 In that case, a disgruntled goat owner, upset that his pet goat Murphy had been ejected from Wrigley Field, laid a curse on the Chicago Cubs that some believe has kept them from winning the World Series right up until the recording of this podcast.

Speaker 1 So then it's only fitting that one of baseball's first bona fide superstars has become more of a myth than a man.

Speaker 1 However, in this case, baseball's first true great isn't remembered as a larger-than-life hero. Instead, he's gone down as one of the most despicable villains of turn-of-the-century America.

Speaker 1 I'm speaking, of course, about the first man ever admitted into the Baseball Hall of Fame in Cooperstown, the Georgia Peach, Ty Cobb.

Speaker 1 Born in Georgia, Tyrus Raymond Cobb played in the major leagues from 1905 to 1928, an impressive 23 years, most of which was for the Detroit Tigers.

Speaker 1 And as any student of the game can tell you, no discussion of the greatest players of all time is complete without a healthy consideration of Ty Cobb.

Speaker 1 One of his contemporaries, pitcher Smokey Joe Wood, had this to say about Cobb, quote, he was the best ball player I ever saw.

Speaker 1

I always said if there was a league higher than the majors, Ty Cobb would be the only fella in it. Just as you'd think about doing something, Ty would be doing it.

He was always one step ahead of you.

Speaker 1

End quote. That's just one of dozens of quotes I could have chosen praising Ty Cobb's ability as an all-around ball player.

Manager Casey Stengel called him, quote, superhuman amazing.

Speaker 1 And Hall of Famer George Sizler said, quote, to see him was to remember him forever, end quote.

Speaker 1 But despite the nearly universal praise for his prowess on the ball diamond, Ty Cobb has one of the most troubled legacies of any professional athlete. Let me put it this way.

Speaker 1 Ty Cobb's reputation is so bad that saying Ty Cobb is your favorite baseball player is kind of like saying Mussolini is your favorite Italian leader.

Speaker 1 He's been depicted as a heartlessly cruel man who sharpened his spike so he could impale basemen as he slid into the bag.

Speaker 1 He's been called out as an unrepentant racist who was known to respond violently if he felt a black person had paid him any disrespect.

Speaker 1 When he wasn't instigating hate crimes against African Americans, he was outwardly voicing his distaste for Jews and children of all ethnic backgrounds.

Speaker 1 On top of that, or so the lore goes, he was almost psychopathically violent. He was quick to anger and was known to trade blows with teammates, umpires, mouthy fans, and occasionally the disabled.

Speaker 1 And if you believe Al Stump, then Ty Cobb's diabolic temper may have actually driven him to murder.

Speaker 1 The conventional wisdom on Ty Cobb is that he was not only one of the nastiest men to play baseball, he may have been one of the worst Americans of his era.

Speaker 1 A 2004 collection of essays named Cobb as a, quote, American monster, alongside Charles Manson and John Wilkes Booth.

Speaker 1 In the comprehensive Ken Burns PBS documentary on baseball, he's cast as a reprehensible villain, and his legacy is neatly summed up as being an embarrassment to the game.

Speaker 1 But is any of this actually true?

Speaker 1 Is Ty Cobb's monstrous reputation deserved, or has this baseball great been unfairly demonized by a mythology that has little in common with the verifiable facts of Cobb's life?

Speaker 1 These are the questions that have been taken on by sports writer and baseball historian Charles Learson in his 2015 biography, Ty Cobb, a Terrible Beauty.

Speaker 1 In this impressively researched book, Learson very carefully analyzes analyzes Ty Cobb's life, with a special focus paid to the more infamous incidences that have fueled the myth that Ty Cobb was a monster.

Speaker 1 Learson's thesis is essentially that Ty Cobb is one of the most misunderstood figures in professional sports history.

Speaker 1 His horrific reputation is mostly the result of exaggerations, false assumptions, and all-out fabrications by both the excitable turn-of-the-century sports press and Cobb's famous biographer, Al Stump.

Speaker 1 Now, what Learson is undertaking in his biography is perhaps one of the trickiest maneuvers in history writing.

Speaker 1 Reviving the reputation of a historical figure who's become almost universally hated is a very delicate dance indeed.

Speaker 1 It's almost easier to tarnish someone's reputation than it is to bring someone's reputation back. Here's what I mean.

Speaker 1 When you call out a historical figure for being a racist or a drunk or participating in some terrible institution, you can then paint yourself as a crusader for truth and justice, and you can lend your voice to the denunciation of a particularly nasty practice.

Speaker 1 When you call out America's founding fathers as slave owners, you therefore identify yourself as someone who finds slavery disgusting.

Speaker 1 When you're taking someone down a notch, you always have righteousness on your side.

Speaker 1 But when you defend someone who's been accused of something particularly nasty, you risk being tarred with the same brush.

Speaker 1 If you defend someone who owns slaves, it can perhaps suggest that you don't think slavery was such a big deal. When you call someone out as a racist, it firmly puts you in the anti-racist camp.

Speaker 1 But when you defend someone who's been called a racist, if not handled carefully, it can seem as though you're defending racism itself.

Speaker 1 Now, for the record, and I think it's important that I make this clear, I am not someone who thinks that the nastier aspects of someone's life should be forgiven or brushed aside just because we find them admirable for one reason or another?

Speaker 1 We shouldn't glaze over or make apologies for things like racism or violence against women in history.

Speaker 1 We should understand the darker aspects of our historical heroes and factor them into our appraisal of them.

Speaker 1 Think about how many artists or musicians or filmmakers or sports stars that you also kind of know maybe did something pretty horrible in their past.

Speaker 1 It can be hard to swallow, but it's important that we know it.

Speaker 1 So, with that said, what should our appraisal of Ty Cobb be? Charles Learson isn't saying that Ty Cobb's villainy should be excused. He's making a much bolder claim.

Speaker 1 He's saying that many of the events that have been held up as examples of Ty Cobb's nastiness either didn't happen or have been unfairly distorted.

Speaker 1 Can we believe Al Stump when he tells us that Ty Cobb left a man dying in the alley? Well, let's take a closer look.

Speaker 1 Now before we can dissect Ty Cobb's legacy as a monster, we should first establish why Ty Cobb is worth talking about in the first place.

Speaker 1 I'm sure many of you who aren't baseball fans have been scratching your heads wondering what all the fuss has been about. I mean, was the guy really that great?

Speaker 1 Well, the answer is an unequivocal yes.

Speaker 1 There's a reason that when the Baseball Hall of Fame was opened in 1936, Ty Cobb received more votes than any other player, including the great Babe Ruth, to be the first man inducted.

Speaker 1 First, let's look at the numbers. Ty Cobb played baseball between the years 1905 and 1928, and in that time, he scored a lifetime batting average of 366.

Speaker 1 That's the best ever, even today.

Speaker 1 No other player in the history of the game has been more successful at bat than Ty Cobb.

Speaker 1 The only season in his career that he batted under 300 was his rookie year, which is incredible considering that he played for 23 years. He batted over 403 seasons in that long career.

Speaker 1 And for those in the crowd that don't understand these baseball stats, let's just say that's crazy good.

Speaker 1 He still holds the record for the most career batting titles at 12, nine of which he won consecutively. So it goes without saying that Ty Cobb was easily one of the greatest hitters in baseball.

Speaker 1 That's especially impressive considering the era in which he played.

Speaker 1 Baseball at the turn of the century is sometimes called the deadball era, named for the decided lack of spring and bounce in the balls used to play the game.

Speaker 1 In those days, the same ball would be used again and again as a type of cost-saving measure by Major League Baseball.

Speaker 1 If you were a fan who caught a foul ball, it was customary to throw it back to one of the fielders so it could continue to be used.

Speaker 1 This meant that the balls became soft and were often encrusted with dirt. Pitchers were also known to employ a little something they called the spit ball.

Speaker 1 This is where they would literally spit on the ball, usually with a mouthful of tobacco juice, in order to give the ball an irregular spin to fake out the batter.

Speaker 1 The tobacco spit also served to make the ball a bit darker, so by the end of the game it was usually an odd shade of brown, which made it trickier for the batter to see.

Speaker 1 All this meant that the ball was, well, kind of dead. Out-of-the-park home runs were rare, to say the least.

Speaker 1 To give you a sense of how much the game was stacked for the defense in this era, the 1906 World Series winners, the Chicago White Sox, were nicknamed the Hitless Wonders.

Speaker 1 The fact that this era also produced one of the game's most dominant offensive players is another credit to Ty Cobb's ability.

Speaker 1 But despite his accolades as a hitter, Ty Cobb is best remembered for his ferocity as a baserunner. He's still fourth in the standings for the most stolen bases in a career.

Speaker 1 And he still holds the record for the most times anyone has stolen home plate at an even 50.

Speaker 1 Stealing home is easily the ballsiest move in all of baseball. And the fact that Ty Cobb holds the record for this is a testament to his playing style, which was, to put it mildly, aggressive.

Speaker 1

And here we have the nugget of the Ty Cobb myth. Ty Cobb played the game with a ferocity that had rarely been seen.

He put his opponents on edge. He was known to play mind games with opposing teams.

Speaker 1 Before stealing a base, he was known to taunt the pitcher by yelling things like, I'm gonna go, I'm going here, I'm gonna go.

Speaker 1 In more than one famous quote, Ty Cobb described baseball as something akin to war.

Speaker 1 But my favorite Ty Cobb quote about baseball has to be the following: quote, Baseball is a red-blooded sport for red-blooded men. It's no pink tea, and mollycoddles had better stay out.

Speaker 1 It's a struggle for supremacy and a survival of the fittest. End quote.

Speaker 1 With sound bites like that, it's easy to see how a legend of a ferocious and hateful man could easily follow.

Speaker 1 Perhaps it should come as no surprise, then, that the most well-known and often repeated myth about Ty Cobb's conduct on the baseball diamond has to do with his ferocity.

Speaker 1 That's the story that he used to sharpen his spikes on his shoes so he could intentionally slash other players when he slid into the bag.

Speaker 1 Now, interestingly enough, spike sharpening was something that happened during this era of baseball. But usually it was used as a garish intimidation tactic.

Speaker 1 Apparently, the Baltimore Orioles of the era were known to make a show out of sharpening their spikes.

Speaker 1 And even Cobb's own Detroit Tigers pulled the stunt once, with a number of players sitting on top of the dugout and menacingly filing their spikes to the delight of the bloodthirsty Detroit fans.

Speaker 1 But notably, Cobb was not one of those players. Cobb never once filed his spikes.

Speaker 1 In fact, he was so upset that he had been associated with the practice that in 1910, he wrote a letter to the American League president asking that players be forced to dull their spikes.

Speaker 1 So how did Cobb get saddled with this myth? Well, as I said before, Cobb's aggressive style meant that there were times that Cobb collided feet first with defending players.

Speaker 1 And sure enough, there were instances where his spikes managed to pierce their skin.

Speaker 1 But this was a notably common occurrence, and many of Cobb's contemporaries defended him by pointing out that he never set out to intentionally wound his opponents.

Speaker 1 In other words, he played rough, but never dirty.

Speaker 1 Charles Learson points out that catcher Wally Shang once said, quote, it's no fun putting the ball on Cobb when he came slashing into the plate, but he never cut me up.

Speaker 1 He was too pretty a slider to hurt anyone who put a ball on him right, end quote.

Speaker 1 And infielder Jeremy Schaefer, a teammate of Cobb's, called him, quote, a game-square fellow who never cut a man with his spikes intentionally in his life, and anyone who gets by with his spikes knows it, end quote.

Speaker 1 But despite the testimonials of teammates and opponents alike, sports writers of the day were eager to cast the aggressive Cobb as a villain and a dirty player.

Speaker 1 His prowess made him a target, and his aggressive style made him dangerous.

Speaker 1 Now, at first, Cobb was happy to let the myth grow that he was a madman on the diamond, but eventually he would become dogged by the belief that he was a dirty player.

Speaker 1 As he neared the end of his life, he became more and more obsessed with the idea of setting the record straight. He wanted to write his own story.

Speaker 1

But despite being a very well-read man, Ty Cobb was no writer. He needed someone to help with the project.

Enter Al Stump.

Speaker 1 In Stump's 1961 article for True magazine, he recounts a conversation with Cobb while visiting a Georgia cemetery where his parents were buried.

Speaker 1 Cobb apparently turned to him and said, quote, my father had his head blown off with a shotgun when I was 18 years old by a member of my own family. I didn't get over that.

Speaker 1 I've never gotten over that, end quote.

Speaker 1 Whether or not Cobb ever said those words to Stump is certainly debatable given Stump's penchant for manufacturing quotes. But the basis of the story is true.

Speaker 1 In 1905, just as Cobb was starting his first year in the major leagues, his mother, Amanda Cobb, shot and killed his father, W.H. Cobb.

Speaker 1 The circumstances of this were very hazy, and even Charles Learson, for all his fact-finding zeal, had a hard time of sussing out the true story.

Speaker 1 The legend goes that Cobb's father suspected Amanda Cobb of cheating on him, so he told her he was leaving town for the weekend and then secretly crept back to their home in the night to see if he could catch her in the act.

Speaker 1 Amanda awoke startled by the sound of someone creeping around outside her house, and assuming that a prowler was skulking around, loaded her gun and proceeded to unload two rounds into her own husband.

Speaker 1 In many ways, the whole incident weirdly mirrors the case of Oscar Pistorius, in that it's still kind of unclear if the whole thing was a tragic accident or an act of malice perpetrated by an angry spouse.

Speaker 1 At trial, Cobb's mother would be found not guilty after the court accepted her defense that the whole incident had been an unfortunate accident.

Speaker 1 The whole crime is very odd, and as Charles Learson points out, the rumors about infidelity may have persisted just as a way to make sense of the strange event.

Speaker 1 Learson, for his part, is suspicious about the story that Cobb's father suspected his wife of cheating.

Speaker 1 He even goes so far as to propose that Cobb's father might have been creeping around that night in order to spy on some ne'er-do-well neighbors and not his wife.

Speaker 1 There isn't any hard proof that his wife was ever unfaithful or that he had any suspicions, but these types of things are often kept quiet. So, the jury's still out.

Speaker 1 The circumstances of Cobb's father's death remain a mystery, but one thing that is clear is that Cobb's mother did not use a shotgun in the attack.

Speaker 1 As I said earlier, Stump quoted Cobb as saying that his father had his head blown off by a shotgun. Now, this is something that is verifiably untrue.

Speaker 1 All contemporary records from the period, including numerous newspaper sources, note that Amanda Cobb shot W.H. with a pistol, not a shotgun.

Speaker 1

The shotgun seems to have been entirely an invention of Al Stump. Now, this might seem like a small point.

I mean, does it really matter if WH was killed by a shotgun or a pistol?

Speaker 1 But it becomes an an issue when in the 1990s, a certain shotgun engraved with Ty Cobb's name and rumored to have been the gun that was used to shoot W.H.

Speaker 1 Cobb starts making the rounds among baseball memorabilia collectors.

Speaker 1 Now, for a while, many of the collectors simply believed that this was the gun that had blown WH's brains out, and that gave it some cachet. But soon, other experts started to question its validity.

Speaker 1 I mean, had Amanda even used a shotgun? I'm pretty sure she used a pistol. Well, eventually some detective work was done and the origin of the shotgun was determined.

Speaker 1 The man who originally sold that shotgun was none other than Al Stump.

Speaker 1 Yes, in later years, Stump was actually using his fabricated biography of Ty Cobb to shill memorabilia, some real and some, like the shotgun, totally fake.

Speaker 1 Now, the gun may have actually belonged to Cobb, but the story that it was a murder weapon was a complete and utter fabrication. And honestly, this is just the beginning.

Speaker 1 Stump would later be called up by memorabilia experts for selling a number of forged letters accredited to Cobb, but written by Stump himself.

Speaker 1

Stump even sold a fake diary that he claimed to hold Cobb's personal thoughts and memories. Every one of those entries had been written by Al Stump.

So, this is the kind of person we're dealing with.

Speaker 1 A man with zero journalistic ethics who made his entire career milking the legacy of Ty Cobb.

Speaker 1 The more evil he made Cobb, the more people wanted to buy his books and eventually buy his phony memorabilia.

Speaker 1 So, if Ty Cobb's most trusted biographer was a liar and a counterfeiter, then we can safely assume that he wasn't the monster that many believe he was.

Speaker 1 If Al Stump is a purveyor of fake history, then does that mean that Ty Cobb was actually a great guy?

Speaker 1 Well, let's not be so hasty. Even if we cancel out all of Stump's fabrications, Ty Cobb still has a complicated legacy that needs to be carefully examined.

Speaker 1 After all, Stump isn't the only baseball historian who came to the conclusion that Cobb was a bad man.

Speaker 1 First of all, there's no denying that Cobb was a violent dude with a short fuse who got into no shortage of scraps in his time.

Speaker 1 He was known to fight with his teammates, people on the street, police officers, and in one storied incident, an umpire.

Speaker 1 Apparently, in 1909, Cobb and umpire Billy Evans decided to settle a disagreement about a call on the field with a scrap underneath the grandstands after the game.

Speaker 1 The fight was only broken up after Cobb started violently choking the umpire.

Speaker 1 Now, Charles Learson has tried to soften this reality by pointing out that the early 1900s were a scrappier time in general, and baseball was a notoriously scrappy sport. Fistfights were the norm.

Speaker 1 Managers were known to punch out players, players were known to punch out fans, and umpires commonly socked anyone who they thought was getting out of line.

Speaker 1 In the early 1900s, fisticuffs was a key part of any honorable man's life, and baseball was a sport full of men whose honor was easily insulted.

Speaker 1 Nevertheless, Cobb was known as a scrappy guy at a time when everyone was a scrappy guy. He was actually arrested more than once for assault and battery and paid a number of fines for his offenses.

Speaker 1 And you can imagine, it took a lot to get the cops involved in those days. In one of the most notorious incidences, Cobb actually beat up a fan who had a disability.

Speaker 1 In 1912, while playing in New York City against the Highlanders, Cobb was mercilessly heckled by a fan who had lost a hand and most of his fingers in a printing press accident.

Speaker 1 After enduring a nearly endless barrage of heckles, Cobb finally snapped. The story goes that the barb that finally put him over the edge had to do with Cobb's mother sleeping around with black men.

Speaker 1 At hearing this, Cobb stormed into the bleachers and proceeded to pummel the man.

Speaker 1 Apparently, members of the crowd begged him to stop, and some even shouted out, he has no hands, to which Ty Cobb replied, I don't care if he has no feet.

Speaker 1 Now, this incident definitely did take place as it was witnessed by hundreds of people. It's certainly evidence that Ty Cobb was not above beating up people who were disabled.

Speaker 1 So add that to your tally when you're making your final appraisal of Cobb.

Speaker 1 But what's interesting is that this incident is also commonly cited as proof of Ty Cobb's racism. Many writers, including Stump, recount this incident with an emphasis on the racially charged heckles.

Speaker 1 The assumption is that Ty Cobb was particularly vulnerable to insinuations that he might not be fully white or that his mother may have had affairs with black men.

Speaker 1 This in turn plays into a much wider narrative that the most despicable thing about Ty Cobb was his unabashed hatred of African Americans.

Speaker 1 But Charles Learson makes a very pointed argument in his biography of Cobb that the man was not the racist that many make him out to be.

Speaker 1 He argues that most incidences that are held up as evidence that Ty Cobb was a bigot were not necessarily motivated by racial hatred.

Speaker 1 Now, I'm not even sure if I'm completely convinced by Learson's argument, but the man's research appears to be impeccable, so we should at least hear him out.

Speaker 1 Learson points out that many authors have attributed Ty's actions to racism when there is, in fact, no proof of racism. Take, for example, the assault on the disabled fan.

Speaker 1 Learson points out that it isn't clear what comment prompted Cobb to rush the stance. It could have been any number of vile things.

Speaker 1 The assumption that the racial comments are the ones that got him the most angry are just that. Assumptions.

Speaker 1 None of the sources from the Times seem to report that the attack was motivated by insinuations about race.

Speaker 1 It was only in later retellings of this story that an explicit connection was made between this attack and Cobb's racism.

Speaker 1 Secondly, a number of violent incidences where Cobb was accused of attacking a black person never actually occurred. Or rather, the attacks occurred, but the victim was not an African American.

Speaker 1 In Charles Alexander's 1984 biography of Ty Cobb, he points to an assault of a butcher, a bellhop, and a night watchman, all of whom he claims were attacked by Cobb because of their race.

Speaker 1 But in his research for his book, Charles Learson discovered that none of these men were African American. In fact, two of these victims actually come from the same incident.

Speaker 1 While staying at a hotel in Cleveland, Cobb got angry with an elevator operator after he wouldn't take Cobb to a floor where a card game was being played.

Speaker 1 Cobb started getting rough with the young man when the night watchman stepped in and the real fight began.

Speaker 1 The two threw each other to the ground and Cobb claims that the watchman actually started jabbing his thumb into one of his eyes.

Speaker 1 Cobb then produced a penknife and raked the watchman across the back of the hand.

Speaker 1 Eventually, the watchman was able to make his way back to the desk where he grabbed a pistol and managed to beat Cobb with the butt of the gun until the baseball player finally passed out.

Speaker 1 Now, once again, this is proof that Ty Cobb was the kind of guy who would rough up a teenager for showing some disrespect and pull a knife in a fight.

Speaker 1 But it's notable that neither the elevator operator or the Night Watchman were black.

Speaker 1 Now, this is important because so many writers have used this incident to prove that Ty Cobb was a racist.

Speaker 1 In all of their retellings, the elevator operator and the Night watchman were African American. But no contemporary records show that these men were black.

Speaker 1 And as Learson points out, that's a detail that the salacious newspapers at the time weren't going to miss.

Speaker 1 The race of these two men has been mistakenly reported even by good biographers like Alexander for years.

Speaker 1 And as the grapevine goes, I've personally heard this story related as, one time Ty Cobb stabbed a black guy for being, quote, uppity,

Speaker 1 which is just completely untrue.

Speaker 1 But perhaps the most notorious incidents of Cobb's racism occurred in 1907 and involved a black groundskeeper named Bungie Cummings. The story's often reported like this.

Speaker 1 Cobb and Bungie had known each other for years, and while Cobb was making his way off the field after a practice, Bungie approached him and made what the Smithsonian magazine called a, quote, overly familiar gesture towards Cobb.

Speaker 1 Cobb, enraged that a black person should be so forward, started beating the man mercilessly. When Bungie's wife then rushed in to try and stop the assault, Cobb grabbed her and started choking her.

Speaker 1 The attack was finally ended when Tiger's catcher Charles Schmidt intervened.

Speaker 1 Now, when I first heard that story, I was pretty disgusted. I mean, to nearly kill a man and his wife for being friendly? I mean, that just seems like a sickening level of hatred.

Speaker 1 And that was proof for me that Cobb was, in fact, an American monster.

Speaker 1 But once again, Charles Learson points out that this incident may not be what it seemed.

Speaker 1 He points out that only three people witnessed the early stages of this encounter, and all of them agreed that Cummings was drunk.

Speaker 1 He then apparently opened his arms and went in for a hug and said, Hello, Carrie, to Cobb, a confusing little jab that Learson speculates may have been a reference to the temperance campaigner Carrie Nation.

Speaker 1 This may have been a light-hearted way to tease Cobb about not drinking alcohol. Apparently, at the time, the best way to tease a teetotaling friend was to say, Who are you, Carrie Nation?

Speaker 1 The witnesses then say that Cobb pushed the man away from him. Then the witnesses didn't report anything else until they saw Cobb and Charlie Schmidt locked in combat.

Speaker 1 So to make that clear, none of the witnesses ever saw Cobb assault Cummings other than a small push to deflect from a drunken hug. And no one ever saw Cummings' wife.

Speaker 1 No one, that is, except for Charlie Schmidt. It was Schmidt that reported that he and Cobb started fighting because he was defending a woman who who was being assaulted.

Speaker 1 Cobb would always maintain that he had never laid a hand on Cummings or his wife, and that Schmidt had invented the whole story specifically to tarnish his reputation.

Speaker 1 Learson adds credence to Cobb's side of things by pointing out that Schmidt had picked fights with Cobb on three occasions before that.

Speaker 1 He also points out that 14 years later, sports writer Hugh Fullerton would discover that Schmidt had indeed been part of a plot to get Cobb tossed from the Detroit Tigers.

Speaker 1 Fullerton discovered that the plan was for Schmidt to bait Cobb into as many fights as he possibly could, essentially making a guy with a quick temper look like a loose cannon.

Speaker 1 Now, unfortunately, no newspaper people at the time thought to ask the Cummings family what had gone on, so we'll never know their side of the story.

Speaker 1 So we're left with a situation where we can either take Cobb's word for it or Schmidt's, and we know that Schmidt was involved in a plot to disgrace Cobb.

Speaker 1 All of this is to say that the incident may not have been the hate crime that it's often painted as.

Speaker 1 Cobb may have been the victim of character assassination.

Speaker 1 In his quest to rehabilitate Cobb, Learson has gone out of his way to point out that Ty Cobb was actually more kind to African Americans than many of his white contemporaries.

Speaker 1 Cobb was often assumed to be a racist simply because he was a white man from Georgia in the early 1900s. But that ignores the fact that Cobb came from a long line of southern abolitionists.

Speaker 1 His great-grandfather actually refused to fight for the Confederacy because he didn't believe in slavery.

Speaker 1 Cobb's father had actually been a state senator who was known to defend the rights of black Georgians in the early days of Jim Crow, and he even once broke up a lynch mob.

Speaker 1 Cobb himself was known to be friendly with black people. We know that Cobb was especially kind to a young African-American bat boy who worked for the Tigers in his early seasons.

Speaker 1 Learson even goes so far as to describe Cobb as the young man's protector.

Speaker 1 Cobb also had an openly affectionate relationship with one of his household servants, a black man who held Cobb in such high esteem that he named his firstborn son, Ty.

Speaker 1 Now, I know that that can sound like the classic excuse for racist behavior. You know, the I can say racist things because I have black friends excuse.

Speaker 1 And the fact that Cobb's one notable black friend was also one of his household staff, maybe that should give you a moment of pause.

Speaker 1 But we should also note that Cobb was one of the few white baseball players from his era who did not oppose the integration of the game.

Speaker 1 He often spoke admiringly about players like Jackie Robinson and Willie Mays.

Speaker 1 When asked about the integration of baseball, Cobb said that black people should, quote, be accepted wholeheartedly and not grudgingly, end quote.

Speaker 1 All of this, paired with the fact that many of the incidences used to point out that Cobb was a racist were either made up or drastically exaggerated, are enough for Charles Learson to exonerate Cobb for the charge of bigotry.

Speaker 1 He makes a strong case,

Speaker 1 but there are still a couple of incidences that give me pause.

Speaker 1 For instance, in 1908, Cobb was arrested after assaulting a black laborer on the streets of Detroit who had told the ballplayer not to step on some freshly laid asphalt.

Speaker 1 Now, it's unclear if he assaulted the man because he was black, or if he assaulted him just because he hit anybody who told him what to do.

Speaker 1 Learson thinks we shouldn't ascribe racial motivations to that one, but I'm not so sure. The newspapers at the time certainly thought that the man's race was an important factor in the fracas.

Speaker 1 Now, those papers may have been exaggerating that aspect to make the whole incident more salacious, but it's still there, and perhaps it shouldn't be ignored.

Speaker 1 There was also a troubling incident in 1919 when it was reported that Cobb hurled racial slurs at a chambermaid named Ada Morris while staying at the Hotel Poncha Train in Chicago.

Speaker 1 When the woman spoke up in protest, Cobb then kicked her in the stomach and down a flight of stairs.

Speaker 1 Chicago's black newspaper, The Chicago Defender, reported that the woman planned to sue Cobb for $10,000 in damages.

Speaker 1 But after that one report, the story quickly disappears, with many speculating that Cobb paid off Morris and her family to keep quiet about the event. Now,

Speaker 1 Learson doesn't really have a good answer for that one. Reputable sources say that happened.

Speaker 1

And so the best he's got is that this one incident proves that Cobb has a dark side. But he doesn't think we should condemn him as a racist because of it.

But I don't know.

Speaker 1 I mean, kicking a lady down a flight of stairs because she took offense to you calling her the N-word?

Speaker 1 I mean, that seems like the most racist thing you could do.

Speaker 1 So was Ty Cobb a racist?

Speaker 1 Well, it seems like he didn't do some of the most notorious things he's accused of.

Speaker 1 It also seems like he believed in the integration of baseball, came from a long line of abolitionists, had some friendly relations with black people, and certainly didn't walk around the street pistol whipping every dark-skinned person he saw, which, believe it or not, was actually claimed by one writer.

Speaker 1 But Cobb is still on the hook for at least two very troubling instances, one of which very clearly had racial motivations.

Speaker 1 So with that in mind, I think it might be just a little hasty to say that Ty Cobb Cobb did not harbor any dark racial prejudices.

Speaker 1 He certainly was not the monster portrayed by Al Stump, but the guy was no angel.

Speaker 1 He may not have hated black people as a rule, but he may have still done a couple pretty terrible things to black people.

Speaker 1 So I'll let you be the judge if the term racist still applies.

Speaker 1 In 1994, Al Stump's largely fabricated biography of Ty Cobb was adapted into a major motion picture called Cobb, starring Tommy Lee Jones in the title role.

Speaker 1

The movie was a bit of a box office flop, but it garnered surprisingly favorable reviews. Even Gene Siskel of Siskel and Ebert seemed to like it.

For my part, I found the movie to be unwatchably bad.

Speaker 1 Not only is the script clunky and cliché, Ty Cobb is presented as the ultimate cartoon character version of himself. In every scene, Tommy Lee Jones fires off a gun and says something like...

Speaker 1 Come on in here and meet the great Ty Cobb!

Speaker 1 Ugh.

Speaker 1 But perhaps the most annoying thing is that Al Stump, played by Robert Wool, is presented as the hero of the story.

Speaker 1 He's the world-famous sports writer who has the unenviable task of writing Cobb's completely falsified autobiography?

Speaker 1 Stump is presented as a noble, if goofy, campaigner for the truth, while Cobb is presented as a psychopathic miscreant intent on distorting his own legacy.

Speaker 1 Knowing what I know now about Al Stump, that's not only darkly ironic, but frankly, kind of insulting.

Speaker 1 Stump, the greatest liar in sports journalism, somehow made himself the hero of the Ty Cobb story. I mean, that's pretty brutal.

Speaker 1 Perhaps even more egregiously, the film serves to perpetuate every dark myth about Cobb that was ever written down, and even invents a few new ones. But notably for us, it also accuses him of murder.

Speaker 1 And this brings us full circle. Apparently, when Charles Learson was researching his biography of Cobb, he got the director of the 1994 biopic on the phone.

Speaker 1 The director told him that it was common knowledge that Cobb had killed at least three people.

Speaker 1 Now, there are a lot of things you can say about Ty Cobb, but accusing him of murder just shows you how out of control the myth of Ty Cobb has become. Ty Cobb never killed anyone.

Speaker 1 He certainly dealt out some pretty heinous beatings in his time, but he never ended another human being's life. The carjacker Cobb left dying in the alley, that was yet another invention of Stumps.

Speaker 1 It appears to be true that Cobb got into a scuffle with some toughs in 1912, but no one wound up dead. The press reports cited by Stump as evidence of the crime doesn't actually exist.

Speaker 1 Researchers went looking for it and found nothing. Learn even went through reports from hospitals to see if someone roughly matching the description of the alleged victim was ever brought in.

Speaker 1 He found absolutely nothing. In other words, Ty Cobb didn't kill a guy.

Speaker 1 So,

Speaker 1 after all of this, what should we make of Ty Cobb?

Speaker 1 Learson's biography paints a picture of a fiercely competitive man who was quick to anger, but who also prided himself as being a gentleman and a scholar.

Speaker 1

He wasn't the psychopath that Al Stump would have us believe. But I think it would be wrong to say that Ty Cobb was a good guy.

He was a complicated guy at best.

Speaker 1 I'm not sure yet if he was a mostly bad person who did some good things in his life or a mostly good person who did some bad things.

Speaker 1 But perhaps all of those categories are arbitrary. Human beings are often a mess of contradictions, and Ty Cobb seems to be no exception.

Speaker 1 What's dangerous is when we take away the nuance from our historical figures and simply cast them as heroes or villains. Ty Cobb the Villain may be more compelling than Ty Cobb the mess.

Speaker 1 But reckoning with the mess?

Speaker 1 Well, that's what history is all about.

Speaker 1 Okay, that's all for this week. Thanks again for listening.

Speaker 1 Before we go this week, I just wanted to remind everyone that our fake history is going to be featured this week on CBC Radio 1's podcast playlist.

Speaker 1 So, for everyone listening in Canada or anyone listening in the United States on Sirius XM,

Speaker 1

you can tune in at 11 p.m. Eastern Time on Thursday, July the 7th, and hear what they have to say about the Our Fake History episode on Shakespeare.

So go check that out.

Speaker 1

And if you miss it on Thursday evening, it will be playing again at 2 p.m. That's Eastern Standard Time on Saturday, this coming Saturday.

That is Saturday, July the 9th.

Speaker 1 A big thank you to CBC for featuring the podcast again. It's very cool for anyone here in Canada.

Speaker 1 They know that the CBC is kind of a big deal, and it's very exciting that the podcast has been featured. Also, I should say happy Canada Day, everyone.

Speaker 1 I know that I was talking about American Independence Day, and I, you know, I wasn't giving props to the home country. So, happy Canada Day, everyone.

Speaker 1 Okay, I just have a couple other programming notes about the show. So, next time you hear my voice, it will be July 18th, and that's when we're having our questions spectacular.

Speaker 1 Yes, it is one year of our fake history, and we are celebrating with a show where I will be answering your questions. Now, I've already gotten a bunch of questions, but I could use more.

Speaker 1

So, again, I will talk to you about history. I will talk to you about my life.

I will talk to you about past episodes.

Speaker 1

I will talk to you about my favorite music, my favorite movies, my favorite stuff in general. I'll really talk to you about anything.

But obviously, I want this show to be interesting.

Speaker 1 So, if you want me to focus on anything in particular, please send me a question. The more I have, the better and the more interesting that show can be.

Speaker 1 Now, after the 18th, the show is going to be taking a little bit of a break.

Speaker 1 To ensure that our fake history keeps on coming into the future, I need to take some time, do some research, plan some episodes, put some stuff in the bank, and that way we can make sure that season two of our fake history is just as successful as season one.

Speaker 1

So, after the question show on July 18th, do not expect another show from me until September 5th. But I am coming back.

Don't unsubscribe. Don't run away.

Don't worry, guys. I'm not going anywhere.

Speaker 1

I'll be back on September 5th with more Our Fake History. But don't worry, we'll talk more about that on the 18th.

You'll still get another dose of me in two weeks' time.

Speaker 1 In the meantime, if you want to get in touch with me, please send me an email at rfakehistory at gmail.com.

Speaker 1

You can also also follow along on Twitter at rfakehistory or go to Facebook. It's Facebook slash R Fake History, like the Facebook page.

Follow along there. Send me messages there.

Speaker 1 Ask me questions there.

Speaker 1 You can also go to rfakehistory.com. You can check out all the cool art for the show.

Speaker 1

My man, Frank Fiorentino, has been creating more and more art for the back episodes. Go into the archives.

Check out all the cool art that he has there in the old episodes.

Speaker 1 He's got some cool new art for the Shakespeare show

Speaker 1

in honor of the CBC appearance. So check that out, please.

You can also donate to the podcast there.

Speaker 1 You can click on the donate to OFH button and you can toss some coins into the tip jar and help yours truly keep the lights on around here.

Speaker 1 The theme music for the show comes to us from Dirty Church.

Speaker 1 You can check out dirtychurch at dirtychurch.bandcamp.com and all the other music you heard on the show today was written and recorded by me.

Speaker 1 My name is Sebastian Major, and remember, just because it didn't happen doesn't mean it isn't real.

Speaker 3 Weight loss solutions are not one-size-fits-all. HERS makes it simpler to get started and stick with a weight loss plan backed by expert-guided online care that puts your weight loss goals first.

Speaker 3 These include oral medication kits or compounded GLP-1 injections. Through hers, pricing for oral medication kits start at just $69 a month for a 10-month plan when paid in full upfront.

Speaker 3 No hidden fees, no membership fees. You shouldn't have to go out of your way to feel like yourself.

Speaker 3 HERS brings expert care straight to you with 100% online access to personalized treatment plans that put your goals first. Reach your weight loss loss goals with help through HERS.

Speaker 3

Get started at forhears.com slash for you to access affordable doctor-trusted weight loss plans. That's forhears.com slash for you.

F-O-R-H-E-R-S.com/slash for you. Paid for by HIMS and HERS Health.

Speaker 3

Weight loss by HERS is not available everywhere. Compounded products are not FDA approved or verified for safety, effectiveness, or quality.

Prescription required. Restrictions at forhears.com.

Apply.