Episode #218 - Did the Siege of Constantinople Even Happen? (Part III)

See Privacy Policy at https://art19.com/privacy and California Privacy Notice at https://art19.com/privacy#do-not-sell-my-info.

Press play and read along

Transcript

Speaker 1 Hey everyone, Sebastian here. Just wanted to let you know that I will once again be participating in this year's Intelligent Speech Conference.

Speaker 1 Deception, lies, fakery, fraudulence, and forgery is what they have on the docket for Intelligent Speech 2025.

Speaker 1 So, obviously, I've got to be there. For those that don't know, Intelligent Speech is an online conference that highlights the best in history podcasting.

Speaker 1 Intelligent Speech 2025 Deception will be taking place on the 8th of February 2025. So, if you want tickets, go to intelligent speechonline.com right now and get yourself to the conference.

Speaker 1 Okay,

Speaker 1 we need to talk about Greek fire.

Speaker 1 This is one of those ancient super weapons that sounds like it should be a historical myth. A chemical weapon capable of creating an unquenchable fire.

Speaker 1

A fire that could not be extinguished using water. A fire that burned on top of water.

A fire that somehow burned underwater.

Speaker 1 When employed at sea, it had the ability to consume wooden ships and all hands unlucky enough to be touched by the ferocious substance.

Speaker 1 Even if a burning sailor managed to plunge into the sea, there was no guarantee that the fire would go out. The burning man might suffocate before the fire did.

Speaker 1 It's the kind of nasty invention that feels very modern, the kind of thing that could only be produced in the antiseptic laboratories of modern arms manufacturers.

Speaker 1 And yet, we're told that this remarkable substance was deployed to devastating effect by the medieval Romans.

Speaker 1 Greek fire sounds like it had to have been made up by some imaginative chronicler, but believe it or not, the historical evidence attesting to its existence is very strong.

Speaker 1 Not only do late Roman sources written in Greek speak of this remarkable weapon, but so too do Arabic, Slavic, and Latin histories, not to mention the descriptions of many eyewitnesses that have managed to survive to this very day.

Speaker 1 This stuff was real, but its destructive power seems to have inspired a healthy amount of legend.

Speaker 1

Even modern historians have a habit of getting hyperbolic when they write about this substance. The mid century Byzantine expert E.

R. A.

Souter once wrote,

Speaker 1 The first appearance of Greek fire was comparable in its demoralizing influence to the advent of the atomic bomb, at least in the limited area of Byzantine action.

Speaker 1 Both Byzantines and Arabs agree that it surpassed all other incendiary weapons in destruction and terror. ⁇ End quote.

Speaker 1 That's quite a claim.

Speaker 1 This weapon wasn't just a nasty little addition to the Roman arsenal. It was a game changer with a psychological effect on par with the atomic bomb, at least according to ERA Souter.

Speaker 1 While it's certainly tempting to challenge that bold historical comparison, there's no denying that the recipe for Greek fire was guarded in a way that seems to presage how states attempted to keep a lock on their nuclear secrets after World War II.

Speaker 1 In the mid-900s, the Roman Emperor Constantine VII wrote a short administrative handbook for future emperors titled De Administrando Imperio.

Speaker 1 In it, he wrote at length about the importance of keeping the secret of the liquid fire weapon.

Speaker 1 Specifically, Specifically, he told his successors that this weapon was not simply developed by clever chemists.

Speaker 1 In fact, it was, quote, shown and revealed by an angel to the great and holy first Christian emperor Constantine, end quote.

Speaker 1 And that angel made the first Constantine swear, quote, not to prepare this fire, but for Christians and only in the imperial city, end quote.

Speaker 1 Not only did God intend this device just for the Romans, it was forbidden to be prepared anywhere other than Constantinople, at least according to that one handbook.

Speaker 1 However, Constantine VII admits that even by his time, the secret had leaked.

Speaker 1 According to the emperor, one traitorous official had accepted a bribe to pass on the recipe of the unquenchable flame to the empire's enemies.

Speaker 1 Thankfully, God intervened before too much damage was done.

Speaker 1 He apparently smote down this traitorous official with, quote, a flame from heaven, end quote, while he tried to enter a church after betraying the secret of the fire.

Speaker 1 Now, obviously, these tales are pure legend. We can say with certainty that Greek fire did not date to the time of Constantine the Great.

Speaker 1 But finding the exact date of its invention can be a tricky thing given our sources.

Speaker 1 The medieval Roman chronicler Theophanes the Confessor is one of the earliest writers who mentions this substance, but he gives us a very confused origin story for the weapon.

Speaker 1 In his chronicle, he mentions that the Roman navy was outfitting its ships with devices that could shoot the burning liquid as early as 668 AD in the lead-up to the alleged first Arab siege of Constantinople that we discussed at length in the last episode.

Speaker 1 But then, a few entries later in the chronicle, Theophanes tells us that actually the substance he calls naval fire was invented by a Roman refugee named Callinicus, who presumably arrived in Constantinople sometime after 668.

Speaker 1 According to Theophanes, Callinicus' naval fire ultimately broke the first Arab siege, but only after the Umayyads had besieged the capital for seven years.

Speaker 1 But as we heard last time, this version of events should not be trusted. The so-called First Arab Siege of Constantinople was likely a huge exaggeration.

Speaker 1 More recent research has suggested that an Arab fleet only threatened Constantinople for about one year around 670, and even that date is disputed.

Speaker 1 We also have good evidence that the fleet made it out of the Sea of Marmara intact and proceeded to raid the Anatolian coastline for another three years.

Speaker 1 You might remember that that fleet was dealt a serious blow by Roman fire ships far from the capital on the southern side of Anatolia.

Speaker 1 But the jury is still out if those fire ships were just run-of-the-mill flaming vessels or ships rigged with Callinicus's naval fire.

Speaker 1 This is all to say that the origins of this liquid fire remain hazy.

Speaker 1 But what's clear is that by the time we get to the year 717 and the second Arab siege of Constantinople, or maybe we should call it the real Arab siege of Constantinople, the Roman navy was now fully equipped with liquid fire.

Speaker 1 So, what exactly was this stuff?

Speaker 1

Well, that has been a source of debate for hundreds of years. The fact that the recipe for this chemical weapon has been lost to time has only added to its mystique.

But we have some clues.

Speaker 1 First, we should clear up some misconceptions. I've been calling this weapon Greek fire throughout this series, because that's the name that most people recognize.

Speaker 1 But it's worth noting that that name is anachronistic and kind of misleading. The name Greek Fire was coined by Western Europeans who encountered the weapon around the time of the First Crusade.

Speaker 1 The Crusaders called the medieval Romans Greeks, Greeks, because Greek had long since replaced Latin as the Eastern Empire's lingua franca.

Speaker 1 It was also the start of a long tradition of undercutting the medieval empire's Roman heritage.

Speaker 1 At the time of the First Crusade, the Eastern Romans still had that burning liquid, and as such, the Westerners dubbed it Greek fire.

Speaker 1 For their part, the Romans never actually called it that. In the sources, it's variously variously called sea fire, naval fire, liquid fire, and prepared fire.

Speaker 1 It's also important to understand that this weapon didn't spring out of nowhere. The comparison to the atomic bomb makes it seem like Greek fire was totally unprecedented in the 8th century.

Speaker 1 This was certainly not the case.

Speaker 1 One of our old friends on this podcast, Stanford University historian and folklorist Adrienne Mayer has explored this in depth in her book, Greek Fire, Poison Arrows, and Scorpion Bombs.

Speaker 1 She's pointed out that ancient people had been using incendiary weapons and enhanced accelerants since the most ancient of times.

Speaker 1 There's evidence that the early Assyrian Empire was using a liquid accelerant as a weapon as early as the 9th century BC.

Speaker 1 Podcast Hall of Famer Herodotus, father of history, father of lies, wrote in the 400s BC of a Persian incendiary weapon created from a quote, dark and evil smelling oil, end quote.

Speaker 1 Famously, this region that we now call the Middle East is filled with huge crude oil deposits.

Speaker 1 Even before the invention of modern drilling technology, there were places where this oil naturally bubbled to the surface. These deposits gave local people access to a substance known as naphtha.

Speaker 1 Adrian Mayer describes it as, quote, a highly flammable light fraction of petroleum, an extremely volatile, strong-smelling, gaseous liquid common in oil deposits of the Near East, end quote.

Speaker 1 In the Middle East, naphtha was a well-known and commonly used weapon of war.

Speaker 1 Mayer has even guessed that the Persian army may have used Naphtha during their burning of Athens and other Greek cities during the storied Greek and Persian wars.

Speaker 1 All the experts seem to agree that Naphtha had to have been part of the Greek fire recipe. Naphtha burnt like gasoline or like an early napalm, which clearly echoes the descriptions of Greek fire.

Speaker 1 Another clue about the recipe comes from a third century AD Roman military manual, usually attributed to one Julius Africanus.

Speaker 1 In it, the author describes the recipe for something he calls automatic fire. He recommends the use of this chemical weapon in the destruction of large wooden siege engines.

Speaker 1 He tells his reader that if this concoction can be surreptitiously painted on enemy siege engines by by night, the morning dew will react with it and will consume the wooden devices in flame.

Speaker 1 Even better, water will not be able to quench the fire and will even add to the flames.

Speaker 1 His automatic fire recipe involved, quote, equal amounts of sulfur, rock salt, ashes, thunderstone, pyrite, black mulberry resin, and zycanthian asphalt, and the tiniest amount of quick lime.

Speaker 1 The quick lime is the key ingredient there. When quicklime and water are mixed, a chemical reaction occurs that produces heat.

Speaker 1 So when the morning dew reacted with the quick lime, it ignited the other accelerants in the mixture.

Speaker 1 So even though we may not have the exact formula for Greek fire, it's likely that it combined elements of the traditional Roman automatic fire recipe with Middle Eastern naphtha weapons.

Speaker 1 This allowed the medieval Romans to create what historian Alex Crosby has called, quote, something new, dreadful, launchable, and flammable, end quote.

Speaker 1 But the formula for this liquid fire was just one piece of the puzzle.

Speaker 1 Historian Alex Rowland has pointed out that Greek fire wasn't just an especially flammable liquid, it was an entire naval weapons system.

Speaker 1 The method of delivery was just as important as the Greek fire juice.

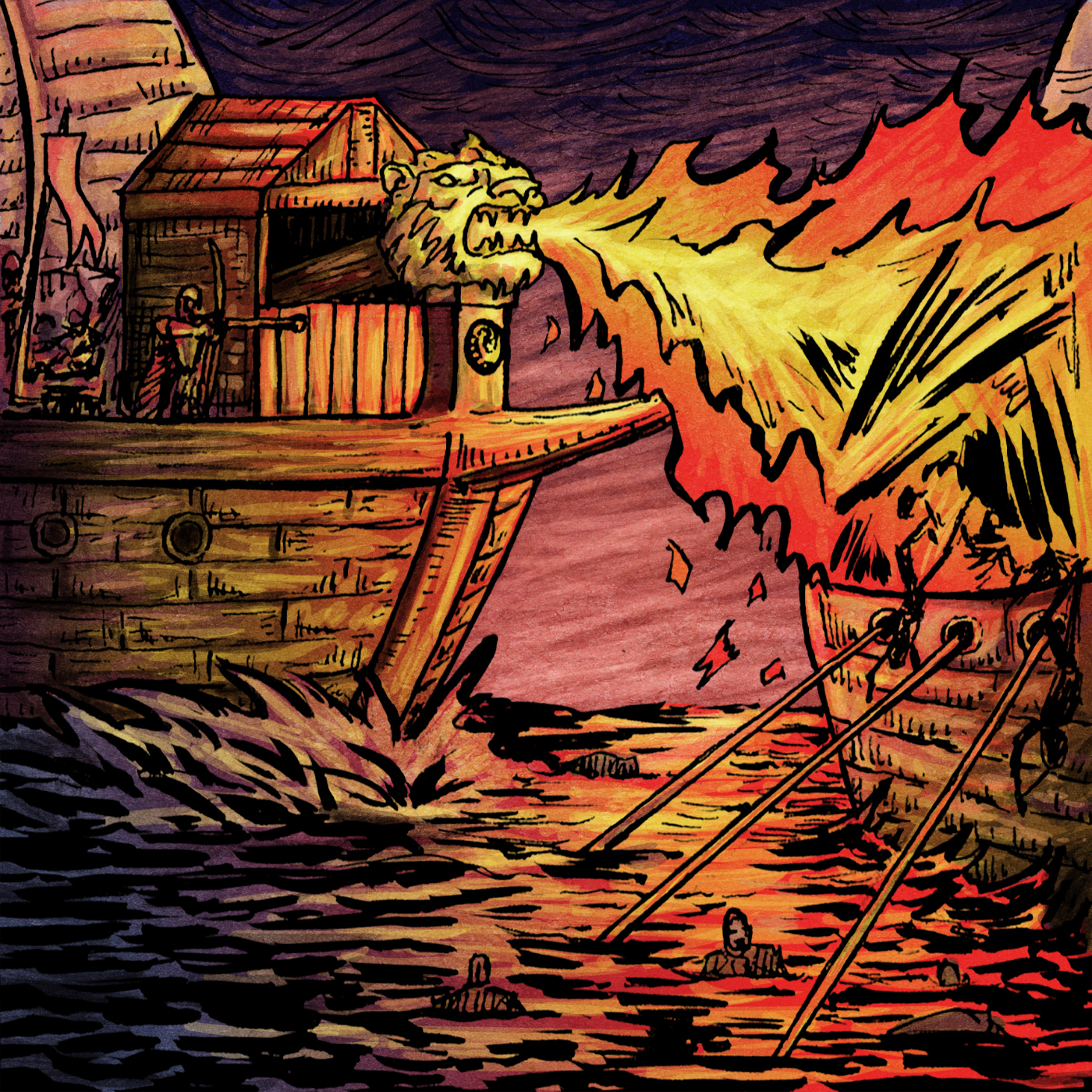

Speaker 1 In the 7th and 8th centuries, the signature warships of the Roman Navy were known as Dromans.

Speaker 1 These were essentially large war galleys powered by rowers that were also outfitted with sails.

Speaker 1 By 717, we know that many of these dromans were upgraded with a system of pumps and siphons that could shoot the flammable liquid.

Speaker 1 Research done by Byzantine expert John Halden has demonstrated that this system also used a large cauldron that was heated by a fire and stoked by large bellows.

Speaker 1 So your sticky, raw, Greek fire goo would be poured into a cauldron and then heated so so it was less viscous and flowed better.

Speaker 1 It would then be pumped through brass tubes towards a flame that would be lit near the muzzle.

Speaker 1 This could be pumped with enough force that a stream of fire that could be directed in different directions would come shooting out of the dromon.

Speaker 1 It's not clear what the range of this naval flamethrower was, but it's been guessed that it could have been around 10 to 15 meters, which, in medieval warfare, isn't too bad.

Speaker 1 The Crusades-era historians also described the fire shooting out of figureheads on the ship's bows that looked like lions and other beasts.

Speaker 1 Now, I'm not sure if that stylistic detail existed in the 8th century, but I like the idea of fire-breathing figureheads at the front of these ships. Ladies and gentlemen, that is badass.

Speaker 1

Once the ignited fluid hit its target, it was nearly impossible to put it out. Like 20th-century napalm, the substance was sticky.

Water had little effect on it. The flames could burn for hours.

Speaker 1 If you were touched with the stuff, it took an enormous effort to avoid being consumed completely.

Speaker 1 Now, over the centuries, other groups would eventually get their hands on Greek fire.

Speaker 1 The Arabs and the Bulgars both managed to either steal the recipe or make off with a quantity of the already manufactured substance.

Speaker 1 But no other culture managed to wield Greek fire as effectively as the Romans. Alex Rowland explains, quote, the key to understanding Greek fire comes in seeing it as a weapons system.

Speaker 1 In this case, the system consisted of a formula, cauldron, siphon, ship, and crew.

Speaker 1 None separately, not even the formula, was capable of achieving what Callinicus' fire achieved at the turn of the eighth century. End quote.

Speaker 1 So, what exactly did Callinicus' fire achieve at the end of the eighth century? To answer that question, we need to take a hard look at the year 717.

Speaker 1 The first Arab siege of Constantinople was likely a phantom created by confused historians, or at least a huge exaggeration of a year-long naval raid.

Speaker 1 But the Umayyad Caliphate did eventually besiege the city of Constantinople properly. It just happened a few decades later.

Speaker 1 But just because the siege of 717 really did occur, that doesn't mean we should trust absolutely everything our sources tell us about it.

Speaker 1 This siege was no phantom, but it was still an early medieval event, which means that legend and myth lurk around every corner.

Speaker 1 Let's pick it apart today on our fake history.

Speaker 1 One, two, three, five

Speaker 1 Episode number 218.

Speaker 1 Did the siege of Constantinople even happen?

Speaker 1 Part 3.

Speaker 1 Hello and welcome to Our Fake History.

Speaker 1 My name is Sebastian Major and this is the podcast where we explore historical myths and try to determine what's fact, what's fiction, and what is such a good story that it simply must be told.

Speaker 1 Before we get going this week, I just want to remind everyone listening that an ad-free version of this podcast is available through Patreon.

Speaker 1 Just head to patreon.com slash our fake history to get access to an ad-free feed and a buttload of exclusive patrons only extra episodes. We're talking hours and hours of our fake history goodness.

Speaker 1 That will include the new extra episode on the Bronze Age collapse requested and voted on by the patrons. That episode will be coming in 2025 once I have completed my research.

Speaker 1 So to get access to that and tons of other goodies, please head to patreon.com slash our fake history and find the level of support that works for you.

Speaker 1 This week, we are wrapping up our trilogy of episodes on the early Arab sieges of Constantinople.

Speaker 1 This is part three in a three-part series. so if you haven't heard the first two parts, I strongly suggest that you go back and give them a listen now.

Speaker 1 The first part of this series looked at some of the historical meta-narratives that are often brought to bear on the conflict between the Eastern Romans and the Islamic Umayyad Caliphate.

Speaker 1 As we saw, there's a long tradition of writing off both the medieval Romans and the early Muslim empires as backwards, superstitious, and decadent.

Speaker 1 However, this often sits awkwardly beside another metanarrative which casts the Eastern Romans as the saviors of Europe who kept the continent from becoming Muslim.

Speaker 1 I have been arguing throughout this series that this perspective is outdated, prejudiced, and deeply inaccurate.

Speaker 1 In part two of this series, we got into the nitty-gritty of the alleged first Arab siege of Constantinople. We explored the remarkable success of the Umayyad navy in the years leading up to 670 AD.

Speaker 1 The Caliphate's ability to challenge the Romans at sea coincided with a number of successful but short-lived land campaigns into Anatolia that brought the Arab armies within sight of Constantinople.

Speaker 1 This set the stage for an attack on the capital.

Speaker 1 But as we saw, the account of Theophanes the Confessor, which is the main source for this attack cited by Western historians, has proven to be deeply unreliable.

Speaker 1 Theophanes tells us of a seven-year siege and then gives us two different stories about the destruction of the Caliphate's fleet.

Speaker 1 First, he tells us that God and his mother destroyed the fleet with a brutal storm.

Speaker 1 And then, a few paragraphs paragraphs later, he tells us, oh, well, actually, the Romans had this cool super weapon called naval fire, and that is what really destroyed the fleet.

Speaker 1 Finally, I highlighted the work of the Oxford historian James Howard Johnston, who has demonstrated that another, largely overlooked historical source, the account of Theophilus of Edessa, gives a much clearer and far more likely version of events in the late 7th century.

Speaker 1 The attack on Constantinople in 670, or perhaps it was 668, if you go with one of the interpretations, was just a one-year affair that was more of a naval raid than a proper siege of the city.

Speaker 1 After threatening Constantinople, the Arab fleet continued raiding down the coast of Anatolia.

Speaker 1 The Umayyads even managed to occupy parts of southern Anatolia before before being defeated in the southern region of Lycia by a Roman army, likely in 674.

Speaker 1 Many experts now accept that the first siege of Constantinople, as described by Theophanes, was a huge exaggeration.

Speaker 1 Now, it's important to know that historians like Merrick Jakoviak have argued that some form of siege may have taken place, but that it likely happened earlier than the sources suggest in the late 660s.

Speaker 1 But even Jakoviak does not accept Theophanes' account.

Speaker 1 Poor Theophanes the Confessor was trying to reconcile a number of different historical sources that used different dating systems and told wildly different stories about the 670s.

Speaker 1 But another reason Theophanes' account of the Arab-Roman confrontation of the 670s was so skewed is that it was likely colored by later events.

Speaker 1 As I've been hinting at throughout this series, the Arab siege of 717 clearly left a big impression on Theophanes.

Speaker 1 When you read Theophanes' account of that later siege, one can't help but notice several elements that seem to echo his account of 670.

Speaker 1 It's possible that he used the siege of 717, a siege that was much better documented, as a template to help him make sense of the contradictory information he had about the 670s.

Speaker 1 So, before we lay this topic to rest, we should take a close look at the events of 717.

Speaker 1 Hopefully, this will help us understand where some of the mythical elements of the first siege came from.

Speaker 1 Now, before we entirely move on from the first siege, I think it's worth mentioning that the Caliphate's attack on Constantinople, whether it was in the late 660s or the early 670s, is attested to in Arabic sources.

Speaker 1 In fact, that first siege even became the setting of a beloved legend about an early Islamic luminary.

Speaker 1 The story goes that one of the last living companions of the prophet, Abu Ayyub, died of an illness during that first siege and had the caliphate's army bury him under the walls of Constantinople.

Speaker 1 From there, a legend grew that even the Christian Romans started venerating the grave site as it was associated with many miracles.

Speaker 1 Now, as far as historical legends go, this is not the most unrealistic tale I've ever encountered.

Speaker 1 The only problem is that the Arabic sources that contain this story were written centuries after the fact.

Speaker 1 As best we can tell, this story first appears in writing in the famous History of Prophets and Kings by the Arabic historian Al-Tabari.

Speaker 1 This work was completed around the year 915 AD, that's some two hundred and forty years after the fact.

Speaker 1 Still, by the time Al-Tabari was writing, it's clear that the reality of the first siege was widely accepted. Al-Tabari may have even been working from Theophanes' flawed account.

Speaker 1 But keep that name Al-Tabari in mind, as he will be one of our key Arabic sources for the siege of 717.

Speaker 1 Now, it seems unlikely that the story of Abu Ayyab is true, but the existence of this story has helped buttress the reality of an exaggerated 670 siege.

Speaker 1 Whether or not you accept the tale, the fact that it's set at the alleged first siege makes that event seem more real,

Speaker 1 or rather rather makes the likely naval attack seem as significant as Theophanes the Confessor has led us to believe.

Speaker 1 This little anecdote also demonstrates that finding out the truth of these events isn't always as simple as comparing the Greek language sources to the Arabic language sources.

Speaker 1 The Arabic sources are certainly quite valuable, but as we will see in the case of the siege of

Speaker 1 they can be just as unreliable and filled with legends as anything produced by the Romans.

Speaker 1 But to set the stage for 717, we need to move through a few decades of history and introduce a whole new set of characters.

Speaker 1 So, let's bring ourselves up to speed and see how the Caliphate found itself on the doorstep of the Roman capital yet again in the year 717. seventeen.

Speaker 2 Discover the power of coding with Codemonkey.com, the award-winning platform trusted by millions of parents and loved by millions of kids.

Speaker 2 As the school year begins, give your child a head start with game-based learning that feels like play. Kids love creating games while mastering real programming languages like CoffeeScript and Python.

Speaker 2 With resources for every grade, Codemonkey makes educational screen time fun and effective. Parents, sign your kids up today and watch them thrive in the digital world.

Speaker 2 Visit codemonkey.com to start with a free trial.

Speaker 1 Mark Twain once famously quipped that history does not repeat itself, but sometimes it rhymes. And my God, is that ever true about the first and second sieges of Constantinople?

Speaker 1 Now, of course, the geopolitical context of the 710s is naturally going to be quite different than the 670s.

Speaker 1 But when taken in from a distance, many elements seem quite similar.

Speaker 1 You might remember that that first push towards Constantinople in the late 660s, early 670s occurred after the Umayyad dynasty emerged victorious from the First Islamic Civil War.

Speaker 1 Well, at the end of the 7th century, the Islamic world was engulfed in yet another civil war.

Speaker 1 In the year 680, the founder of the Umayyad Caliphate and a key player in our last episode, Muawiyah, died in Damascus.

Speaker 1 Before he died, he made the unprecedented choice to name his son, the war leader Yazid, as the next caliph.

Speaker 1 Before that point, the position of caliph had not really been a hereditary office, and there were many in the Muslim world who believed that it should not be.

Speaker 1 So, the death of Muawiyah and the ascension of Yazid opened up many of the old wounds that had not fully healed since the last Islamic civil war.

Speaker 1 The result was yet another long struggle over the question of who should rule the caliphate. This was known as the Second Fitna, and it lasted 12 years.

Speaker 1 This discord in the caliphate meant for the first time in a long time, the Roman Empire was able to assert itself in the region.

Speaker 1 In 678, that is, in the aftermath of the events we detailed in the last episode, the Caliphate and the Romans signed a peace treaty that was supposed to last 30 years.

Speaker 1 Now, you might remember that the Romans won a victory over the Caliphate in southern Anatolia around that time.

Speaker 1 This, paired with a rebellion in Syria, meant that the Romans were able to get some excellent terms at the negotiation table. The Caliphate ended up agreeing to pay a yearly tribute to Constantinople.

Speaker 1 Now, our old buddy, the Emperor Constantine IV,

Speaker 1 used this peace to shore up the defense of the empire.

Speaker 1 He reasserted Roman control over many of the border areas and recaptured parts of the empire that had been taken by the Bulgar people in the northwest.

Speaker 1 This meant that when Constantine IV died in 685, he left the empire in better shape than he found it.

Speaker 1 The historian Edward Gibbon's withering assessment that Constantine IV was a disgrace to the name Constantine may have been a touch harsh.

Speaker 1 But Constantine's successor, his son Justinian II,

Speaker 1 is a different beast altogether.

Speaker 1 He's the type of figure that we often cover on this show.

Speaker 1 That is, someone whose historical reputation is so bad that many modern historians wonder how much of it is true and how much is slander cooked up by his many enemies.

Speaker 1 Now, we could easily get lost in a Justinian II rabbit hole here.

Speaker 1 So I'm going to make this as brief as possible, with the caveat that everything we know about Justinian II and his reign is hotly debated.

Speaker 1 Like Caligula and the other quote-unquote bad Roman emperors, he may have been the victim of a hostile historical tradition.

Speaker 1 To give you a feel for this, I'm once again going to turn to the venerable author of the decline and fall of the Roman Empire, Edward Gibbon. He described Justinian II like this.

Speaker 1 Quote, His passions were strong, his understanding was feeble.

Speaker 1 He was intoxicated with a foolish pride, that his birth gave him the command of millions, of whom the smallest community would not have chosen him for their local magistrate.

Speaker 1 Justinian, who possessed some vigor of character, enjoyed the sufferings and braved the revenge of his subjects about ten years, till the measure was full of his crimes and of their patience.

Speaker 1 End quote.

Speaker 1 So,

Speaker 1 how seriously should we take this assessment? Well, it's hard to say, but there is a long tradition that has judged Justinian II Second to be a monster.

Speaker 1 What's generally undisputed is that he was militarily quite aggressive. At first Justinian had some success expanding the borders of the empire to the northwest.

Speaker 1 But then, in 692, he made the fateful decision to poke the bear.

Speaker 1 He broke the peace with the caliphate and started attacking Umayyad positions.

Speaker 1 This was a disastrous choice because just as he chose to do this, the Umayyads were wrapping up their civil war.

Speaker 1 The Umayyad dynasty had survived 12 years of military challenges to their rule and now for the first time in over a decade they were in a position where they could properly counter the Romans.

Speaker 1 Justinian II's aggression opened up another 25 years of war between the Romans and the Caliphate that would ultimately culminate in the 717 siege of Constantinople.

Speaker 1 In 692, Justinian's forces were decisively beaten by the Caliphate at the Battle of Sebastopolis, which opened the door for the revived and newly focused Arab forces to peel off huge sections of Roman territory in Armenia and beyond.

Speaker 1 In that year, he was deposed in an uprising led by one of his military governors.

Speaker 1 Now,

Speaker 1

interestingly, Justinian II was not killed in this coup, as often happened. Instead, he was exiled.

But before he was, the new emperor had Justinian's nose cut off of his face.

Speaker 1 This is why you might see Justinian II referred to as Justinian the Slit-nosed.

Speaker 1 How's that for a title?

Speaker 1 Now, this kind of punishment was actually somewhat common in this era of Roman history.

Speaker 1 It was believed that someone disfigured in this way would not be accepted as the emperor, even if they tried to return.

Speaker 1 But Justinian the slit-nosed proved them all wrong.

Speaker 1 Now, perhaps we should take this with a grain of salt, but we're told that while in exile, the former emperor took to wearing a prosthetic nose made of gold.

Speaker 1 He also started making plans for how he could retake the throne.

Speaker 1 Now, this is super villain level stuff here. A disgraced former emperor wearing a gold nose out on the fringes of the empire plotting his revenge.

Speaker 1 If they have not used this for a Star Wars sequel, they probably should.

Speaker 1 And sure enough, in 705, Justinian II appeared before the gates of Constantinople at the head of an army 15,000 strong made up of Bulgar and Slav horsemen.

Speaker 1 The gates were opened, and Justinian II was reinstated as emperor. This broke the long Roman tradition of denying imperial power to a mutilated person.

Speaker 1 And perhaps there's a lesson here about power-hungry people being undeterred by humiliation, disgrace, and marks of shame. Even someone with no nose can mount an unlikely comeback.

Speaker 1 They'll just strap on a gold nose and promise the thrill of revenge and rewards for the loyal.

Speaker 1 Anyway, to make a long story short, Justinian's second reign lasted another six years before he was once again overthrown by a revolt in 711.

Speaker 1 This time, they didn't take any chances, and he was executed.

Speaker 1 This whole period from 695 to 715 has been dubbed by historians the 20 years anarchy.

Speaker 1 This is because in those periods when Justinian II was out of power, there was a parade of short-lived emperors and a never-ending series of political crises.

Speaker 1 After Justinian was deposed for the second time, there were three different emperors, each of whom ruled for around two years apiece before being deposed themselves.

Speaker 1 Now, all of this was great for the newly re-energized Umayyad Caliphate. While the Romans were in the throes of their 20 years anarchy, the Muslims were once again on the march in Roman territory.

Speaker 1 So, just like the run-up to the 670s and the alleged First Siege, we have a situation where the Romans are reeling from a political crisis and a series of deposed emperors, and the Caliphate has emerged from a civil war ready to focus their military energy on the Roman Empire.

Speaker 1 Sometimes history rhymes.

Speaker 1 Traditionally, historians credit one figure with finally ending the 20 years anarchy and bringing some political stability back to the Roman Empire.

Speaker 1 This was the man who ended up leading the Romans through the siege of 717.

Speaker 1 He was born with the name Conan, honestly, pretty cool, but would be known to history as Emperor Leo III.

Speaker 1 Leo is a very important player in this story, and unlike so many other people from this period, we get a real sense of his character from the sources.

Speaker 1 In fact, Leo's character is a key part of the story of the siege.

Speaker 1 Interestingly, all of our sources, be they Greek or Arabic, seem to agree that Leo was one slippery customer.

Speaker 1 He was intelligent, but also deceptive, tricky, and brilliantly manipulative. He could talk his way out of almost anything.

Speaker 1

Ladies and gentlemen, for the second time this season, we have a Riz King on our hands. Leo III had that Riz.

He could Riz him up. He was the Rizzler.

Speaker 1 Now, our source for most things Leo is once again the Chronicle of Theophanes the Confessor.

Speaker 1 But where Theophanes had eight sentences detailing an alleged seven-year siege starting in 670, he has many pages describing the life and career of Leo III, complete with direct quotes from Leo.

Speaker 1 As such, many experts believe that Theophanes must have been working from a detailed biography of Leo that was produced during the emperor's reign, but has since been lost.

Speaker 1 But as our friend Robin Pearson, host of the History of Byzantium podcast, has pointed out, all this extra detail in a chronicle that's otherwise pretty terse is a little suspicious.

Speaker 1 When Robin was looking at Leo III for his podcast, he made the point that Leo sometimes comes off a bit like the famous mythological hero Odysseus.

Speaker 1 As all my Greek mythology heads know, Odysseus was celebrated as the trickiest of the Greeks.

Speaker 1 He came up with the ruse of the Trojan horse, and over the course of the epic poem The Odyssey, he used his wits to get himself and his crew out of a number of sticky situations.

Speaker 1 Now, Robin made the point that the life of Leo III kind of flows like the Odyssey in reverse.

Speaker 1 Leo uses his intelligence to outwit a number of enemies so he can return to a great city and save it from a siege. Now, I really liked that insight.

Speaker 1 So shout out to Robin Pearson and all the good work he does over at the History of Byzantium podcast.

Speaker 1 So I think we should keep that all in mind while we're discussing Leo.

Speaker 1 This is far from proven, but I think it's worth considering the idea that his biography may have been shaped or influenced by a mythical template.

Speaker 1 So what do we know about this guy? Well, Leo was born in the borderlands region between southern Anatolia and Syria.

Speaker 1 This is a part of the map that at the time was known as Isauria, hence his nickname Leo the Isaurian.

Speaker 1 Theophanes tells us that during Justinian II's first reign, Leo's family ran afoul of the emperor.

Speaker 1 But during the second reign, Leo got into Justinian's good graces after gifting old gold nose 500 sheep.

Speaker 1 Happy with this gift and always pleased when former enemies kissed the ring, the fickle emperor honored Leo by making him a Spatharios.

Speaker 1 This was a title used for imperial bodyguards and imperial attendants.

Speaker 1 But Theophanes tells us that not long after Leo entered the emperor's service in Constantinople, unjustified rumors started spreading that Leo was secretly plotting against Justinian.

Speaker 1 So, if we trust our famously untrustworthy source, Justinian tried to get rid of Leo by sending him on an impossible errand.

Speaker 1 Leo was sent on a mission to the fringes of the empire in the Caucasus mountain region.

Speaker 1 There he was supposed to treat with a group known as the Alans, a nomadic horse archer culture who could potentially be helpful allies in the fight against the Caliphate.

Speaker 1 Leo was told that the emperor would be sending along some cash behind him to help him convince the Alans of allying themselves with the Romans.

Speaker 1 But after Leo arrived in the Caucasus, it became clear that the money was not coming.

Speaker 1 Now, Leo had to rely on his charm to get himself safely back home. And charm he did.

Speaker 1 First, he charmed the pants off the Alans, who promised to protect him even though it was clear that they were not going to get paid. Why would they do this? Well, they liked the guy.

Speaker 1 Eventually, the Alan leader agreed to provide Leo with some snowshoes and an escort of Alan riders to take him back across the Caucasus Mountains.

Speaker 1 While in the mountain passes, Leo met a group of 200 Roman soldiers who had turned to banditry after having fled from an Arab attack in the region.

Speaker 1 Once again, Leo turned on the charm, and boom, this group of soldiers agreed to follow the Spatharios back to Roman territory.

Speaker 1 Along the way, Leo managed to take a strategically situated fort using trickery, carefully arranging his ragtag group of Alan horsemen and runaway Romans to appear far more mighty than he actually was.

Speaker 1 Eventually, Leo and his crew made it back to Roman territory, only to learn that Justinian II had been overthrown once again.

Speaker 1 And this time, Goldnose was dead.

Speaker 1 Upon returning to the capital, Leo found himself welcomed by the new emperor, a certain Anastasius II, who promptly promoted the wily Leo to be the head of a military jurisdiction known as the Anatolicon Theme.

Speaker 1 This made Leo a powerful military governor in command of one of the empire's largest armies.

Speaker 1 Now, I'm sure you're thinking to yourself, wow, that happened quickly. And it is a little unclear exactly why Leo was so readily picked for this extremely important role.

Speaker 1 Most historians believe that it's likely that Anastasius and Leo had a previous relationship while serving in the court of Justinian. But that's just a guess.

Speaker 1 In this era, Roman politics turned on a dime. And sure enough, less than two years later, the Emperor Anastasius had had been overthrown in yet another coup.

Speaker 1 The rebellious soldiers behind the coup installed an ill-prepared former tax collector, rebranded as Theodosius III, to serve as their puppet king.

Speaker 1 Now, by this point, our guy Leo was one of the most powerful governors and generals in the Roman Empire. And he wasn't so sure he was going to support this new upjumped tax collector.

Speaker 1

So Leo started plotting with one of his fellow military governors to just keep the coups rolling. The new emperor shouldn't be some tax collector.

It should be Leo.

Speaker 1 Now through all of this, the Caliphate had been using the chaos in the Roman Empire to score victory after victory against the Romans.

Speaker 1 By the year 716, the Caliph in Damascus was a man named Suleiman, who had made aggression against the Romans one of the central features of his foreign policy.

Speaker 1 In the decades leading up to the siege of 717, the Caliphate had turned campaigning in Anatolia and the other Roman territories into a yearly event.

Speaker 1 This usually took the form of raiding and looting expeditions, but also included the occupation of many of the contested border territories like Armenia.

Speaker 1 The latest wave of Roman coups and counter-coups created an opportunity for Suleiman to do what even the great Muawiyah could not, capture Constantinople.

Speaker 1 How important was this to the Caliph Suleiman?

Speaker 1 Well, experts debate this point, but one source tells us that he vowed to, quote, not stop fighting against Constantinople before having exhausted the country of the Arabs or to have taken the city, end quote.

Speaker 1 What's clear is that by the year 716, the Caliph had built an army in Syria large enough to seriously threaten Constantinople's Theodosian walls.

Speaker 1 He also had a fleet capable of blockading Constantinople by sea.

Speaker 1 It had taken the Caliph years to build this force.

Speaker 1 So when news came through Damascus that Leo, a potentially rebellious Roman military governor, was considering launching another coup, the Caliph got some ideas.

Speaker 1 Perhaps the Caliph could take Constantinople without having to spend much blood or treasure at all.

Speaker 1 Perhaps this Leo could become a puppet of the Caliphate.

Speaker 1 So we're told that the caliph split his invasion force in two. The first, smaller force, was sent into Anatolia under the command of a general, also confusingly named Suleiman.

Speaker 1 But Suleiman was a subordinate to the real general who would be behind this siege, Maslama ibn Abdal-Malik, who we will just call Maslama.

Speaker 1 Anyway, we're told that the general Suleiman entered Anatolia first in 716.

Speaker 1 He and his army headed straight for the fortress city of Amorium, which was acting as Leo's headquarters.

Speaker 1 The Muslim army camped outside the walls of Amorium, and the general had them all chant, all hail Emperor Leo in Greek.

Speaker 1 Now, for Leo, this was a fascinating development.

Speaker 1 What was an army from Damascus doing hailing him as emperor? Hmm.

Speaker 1 So after a bit of back and forth, Leo agreed to meet with the General Suleiman.

Speaker 1 At the meeting, Leo was told that the Caliphate would support him in his quest to become the king of the Romans, so long as he opened the gates of Constantinople to the Caliph's generals.

Speaker 1 After that, he would be made a a client king who would be fairly independent so long as he paid his respects to the caliph in Damascus.

Speaker 1 Now,

Speaker 1 this is where Leo really gets his reputation for being tricky.

Speaker 1 We're told that Leo agreed to all of this and let the General Suleiman place him under a type of loose house arrest.

Speaker 1 According to Theophanes, in the negotiations, Leo also convinced the general Suleiman that he would eventually be opening the gates of the fortress city of Amorium to his troops as well.

Speaker 1 So there was no need to launch a costly attack.

Speaker 1 In the meantime, a message was sent to the head general Maslama, who had just started bringing his army into Anatolia.

Speaker 1 Maslama was told that the way to the capital had been cleared as Leo's Leo's troops had been told to stand down.

Speaker 1 But then Leo pulled a classic Leo move.

Speaker 1 Not long after making this deal, Leo asked his Arab guards if he and a small entourage could go hunting. They agreed, thinking that Leo was fully bought and paid for.

Speaker 1 When he was out on the hunt, Leo and his crew gave the Arabs the slip, rode off, and rendezvoused rendezvoused with his still loyal forces.

Speaker 1 He then sent a long series of letters to the Arab generals, assuring them that the deal was still totally on. It was just that they had seized him in a way that was unbecoming.

Speaker 1 For his safety, he needed to keep his forces on alert.

Speaker 1 Before the Arab generals could fully appreciate what had happened, Leo ordered 800 fresh troops sent to the fortress of Amorium.

Speaker 1 This meant that a city that the Muslims had thought was all but captured actually wasn't so captured after all.

Speaker 1 This meant that the path to the capital wasn't quite as clear as had originally been assumed.

Speaker 1 Now, this didn't really change the plan to take Constantinople, but it certainly slowed down the Muslim forces.

Speaker 1 Maslama had been planning to winter his army at Leo's fort at Amorium, a fort he thought he had just taken through a well-placed bribe.

Speaker 1 Leo's escape meant that Amorium would remain garrisoned with Roman troops, and Maslama was not about to waste his resources taking the fort by force.

Speaker 1 This meant that the army had to march further west than had been originally planned. With Maslama and Suleiman redirected, Leo made his move on Constantinople.

Speaker 1 He marched hard for the capital with his loyal army at his back.

Speaker 1 Along the way, he took the city of Nicomedia, where he had the good fortune of capturing the son of the sitting emperor, the overwhelmed tax collector Theodosius III.

Speaker 1 When Leo showed up at the gates of Constantinople with his army and the emperor's son, he had a very simple proposal. Open the gates, hand over power to me, and nobody gets hurt.

Speaker 1 Theodosius agreed to this almost immediately, and he and his son were allowed to retire peacefully in a monastery.

Speaker 1 Now, this has led many historians to conclude that Theodosius III never really wanted to be the emperor.

Speaker 1 The group of soldiers who had put Theodosius on the throne also did not put up much of a fight when Leo turned up at the gates.

Speaker 1 It was now common knowledge that the Caliphate had a massive army, some sources say 80,000 strong, and a fleet that may have numbered 1,800 ships. They were all being pointed at the capital.

Speaker 1 Theodosius, the tax collector, was not the man for the moment. A wily general like Leo, on the other hand, might just be what the doctor ordered.

Speaker 1 And just like that, the boy-born Conan became Emperor Leo III.

Speaker 1 He charmed, deceived, and maneuvered his way right to the top job.

Speaker 1 He was installed as emperor in March of 717.

Speaker 1 Maslama and his army would be at the gates by July.

Speaker 1 Now, there are all sorts of reasons to distrust the story I just told you. Remember, Theophanes was likely working from a biography that had been approved by Leo.

Speaker 1 And honestly, Leo III really comes across like the main character of this story.

Speaker 1 Also, you may have noticed that Theophanes' account has some weird plot holes. So, was all of that fake history?

Speaker 1 It's not out of the question.

Speaker 1 But it is clear that in 717, Leo pulled off an unlikely coup. He grabbed the reins of power in Constantinople and quickly put the whole city on a war footing.

Speaker 1 So, let's take a break here, and when we come back, we'll see how the second siege of Constantinople played out.

Speaker 1 In the year 717, the Emperor Leo III had just a few short months to prepare the city of Constantinople for war.

Speaker 1 Luckily, the Romans had been aware for years that a large attack was coming from Syria. The massive buildup of ships and troops had not been missed.

Speaker 1 Many assumed that an attack on Constantinople was only a matter of time.

Speaker 1 Still, supplies were hoarded, fortifications were repaired, and the navy, now outfitted with the liquid fire weapons system, was put on high alert.

Speaker 1 For the first time in history, a large chain was drawn up across the mouth of the Golden Horn.

Speaker 1 You might remember that the Golden Horn is the inlet that comes off of the Bosphorus Strait, which gives Constantinople one of its excellent protected harbors.

Speaker 1 The large chain, which stretched from one side of the inlet to the other, could be tightened or loosened to close the Golden Horn to unwanted ships.

Speaker 1 But most significantly, Leo made a deal with the Bulgars, the semi-nomadic horse warriors who dominated the former imperial territories of the Balkans.

Speaker 1 Now, trying to get a sense of the numbers involved in this siege is difficult. As I said earlier, Maslama was said to have 80,000 troops, but it's likely that that number is a bit inflated.

Speaker 1 But most experts agree that an army of between 30,000 to 50,000 soldiers was not out of the question.

Speaker 1 According to the author of The Byzantine Art of War, Michael Decker, the Romans could not have had more than 15,000 armed defenders in the city. Potentially, there were even less.

Speaker 1

So, any way you slice it, the Romans were enormously outnumbered. This meant that the Romans were in no position to sally forth from behind the Theodosian walls.

This is where the Bulgars came in.

Speaker 1 Now, the terms of the deal between Leo and the Bulgar leader are not recorded, but Leo was able to offer the Bulgars enough that they agreed to keep the army of the Caliphate off balance.

Speaker 1 If Maslama's army started venturing too far north of the city, they could expect to meet the Bulgars.

Speaker 1 In either mid-July or mid-August of 717, Maslama's land army appeared before the Theodosian walls.

Speaker 1 This army came for the long haul.

Speaker 1 The Arabic chronicle, the Kitab al-Uyan, claims that Maslama brought with him enormous stockpiles stockpiles of food.

Speaker 1 Apparently, the stacks of wheat brought by the army were so large that they formed huge towers that could be seen from the city walls.

Speaker 1 This massive land force was accompanied by a huge fleet that Theophanes tells us was 1800 ships strong. Once again, most experts think this number is inflated, but likely not by much.

Speaker 1 By midsummer of 717, the siege was officially on.

Speaker 1 One of the first key maneuvers attempted by the Umayyads was to try and impose a tight naval blockade on the city.

Speaker 1 The Arab fleet had entered the Sea of Marmora at its westernmost point and were sailing towards Constantinople, which was at the sea's easternmost point.

Speaker 1 This meant that blocking off the southwestern end of the Bosphorus Strait, near the Sea of Marmara, was easy enough.

Speaker 1 Trickier would be sailing up the Bosphorus past the city of Constantinople to block the northeastern end of the strait. That way, the city could not be resupplied from the Black Sea.

Speaker 1 The best case scenario for the Umayyads would be if they could also take control of the Golden Horn. If Maslama could take the Golden Horn, that would mean neutralizing the Roman navy.

Speaker 1 It would also make it harder for the Romans to feed themselves by fishing, as the fishing boats would be penned into harbor.

Speaker 1 So, a perfect blockade meant controlling both ends of the Bosphorus Strait and the Golden Horn.

Speaker 1 With that in mind, Maslama made his move.

Speaker 1 Not long after the arrival of the fleet, a squadron was tasked with sailing up the Bosphorus Strait and securing a port in the northeast to cut off access to the Black Sea.

Speaker 1 If they were successful, then from there they would make their move on the Golden Horn.

Speaker 1 They waited for a favorable wind from the south and then headed out.

Speaker 1 Now this squadron was headed by the much faster Arab warships, while large troop transports, each holding around 100 soldiers each, followed behind.

Speaker 1 But as I mentioned before, sailing the Bosphorus Strait is no easy thing. A strong current makes sailing north towards the Black Sea difficult if you aren't experienced with the waters.

Speaker 1 And so it was as the Arabs were sailing to the northeast, their helpful southerly wind died.

Speaker 1 This meant that a gap opened up in the line of ships as the faster warships pulled ahead and the sluggish troop transports started to be pushed back south by the current.

Speaker 1 Theophanes tells us that when the Emperor Leo saw this gap open up in the line of ships, he personally gave the order for his navy to attack.

Speaker 1 First, two flaming fire ships were sent towards the transports caught in the current. Then came the powerful Dromon warships, all fitted out with liquid fire.

Speaker 1 The Dromons bore down on the stranded transports and doused them with their unquenchable flames.

Speaker 1 The Arab warships at the front didn't even engage, as turning the large ships in the current would have left them vulnerable.

Speaker 1 The Romans burnt at their leisure, and the Arabs watched horrified as they saw their comrades unable to extinguish the flames, even when they jumped in the sea.

Speaker 1 In the end, the Romans were able to burn around 20 ships, which could have held as many as 2,000 soldiers and sailors.

Speaker 1 Now, when you're commanding a fleet of 1,800 ships, losing 20 isn't really a disaster. But Theophanes tells us that the liquid fire attack had a huge psychological effect on both sides of the siege.

Speaker 1 He writes, quote, the inhabitants of the city took courage, whereas the enemy cowered with fear after experiencing the efficacious effect of the liquid fire. End quote.

Speaker 1 Even though enough of the Umayyad fleet made it through the Bosphorus Strait and were able to block the Black Sea approach to the city, the Arabs became incredibly wary of approaching too close to the Golden Horn.

Speaker 1 After this first naval engagement, the chain was pulled tight across the mouth of the Horn, and the threat of Greek fire kept the Arabs from trying to break that chain.

Speaker 1

So this meant that the Golden Horn remained accessible to the the Romans. Maslama had a blockade of sorts, but it was kind of loose.

The Roman navy was still very much in the mix.

Speaker 1 After that first engagement, the two sides buckled down. Maslama started running a fairly classic siege.

Speaker 1 The main force of the army camped in front of the walls, while the fleet blockaded the waterways. From there, his forces freely raided the nearby suburbs and countryside.

Speaker 1 Summer gave way to fall and fall to winter, with neither side showing any signs that they were about to give up.

Speaker 1 Now, our Arabic sources tell us that as the first winter drew near, negotiations opened up between the two forces.

Speaker 1 This is interesting because the Roman sources say nothing about this.

Speaker 1 It's the Arabic historians that give us one of the greatest stories about both the siege and Emperor Leo that we have recorded anywhere. So, let's get into this.

Speaker 1 We're told that throughout the siege, Leo remained in communication with the general Maslama and kept up the ruse that he was their man on the inside.

Speaker 1 In his letters, he constantly told the Umayyad general that he would be opening the gates any day now.

Speaker 1

He just needed to be careful lest his fellow Romans get suspicious and depose him before the Muslims could enter victoriously. He had to do this just right.

I'm sure you understand.

Speaker 1 Eventually, Maslama lost his patience with this and told Leo that it was now or never.

Speaker 1 To this, the Roman emperor allegedly responded that the issue were the enormous piles of wheat that the Umayyads had at their camp.

Speaker 1 The fact that these piles were so huge that they could be seen from the city walls meant that the people of Constantinople knew that the Muslims wouldn't be attacking anytime soon.

Speaker 1 The Roman people were confident that their city of Constantinople would outlast the invaders if it was simply going to be a contest of who would run out of food first.

Speaker 1 After all, their city was well stocked, and the fact that the Golden Horn was still theirs meant that they could fish.

Speaker 1 But, Leo continued, the people of Constantinople might accept a quick surrender if they thought the giant Umayyad army was about to storm the walls.

Speaker 1 The threat of an attack might spook them into a surrender.

Speaker 1 So,

Speaker 1 Leo advised Maslama to put on a show like he was about to storm the walls.

Speaker 1 Step one, burn all your food.

Speaker 1 Yes, Leo encouraged Maslama to set his giant stacks of wheat on fire so the bonfires could be seen from the city walls. Now, why would the Muslims do this?

Speaker 1 Well, why else would you burn your food unless you are about to assault the walls?

Speaker 1 Leo assured Maslama that once word spread that the Muslims were burning their food, the people of the city would be so afraid that they would accept a surrender and would allow him to open the gates.

Speaker 1 But, Leo added, before food was burnt, Maslama should do one more thing that would really seal the deal.

Speaker 1 He should take one of his largest transport ships and load it full to the brim with wheat and other supplies.

Speaker 1 This food shipment should be sent peacefully to Constantinople's harbor as a sign of goodwill.

Speaker 1 The shipment of food would demonstrate to the Romans that the people of the city would be well taken care of once they surrendered to Maslama.

Speaker 1 It was a bold proposal. And amazingly, unbelievably, even, Maslama agreed to this outrageous plan.

Speaker 1 He loaded a boat full of food and other supplies, sent it to the Romans, and then ostentatiously burned his carefully stockpiled supplies in giant bonfires.

Speaker 1 And then

Speaker 1

nothing happened. The gates of Constantinople remained closed.

When Maslama sent a message to Leo asking when he was going to live up to his side of the bargain, Leo apparently said,

Speaker 1 I have no idea what you're talking about. Why would I open the gates? Why would I betray my religion and my people?

Speaker 1 So sorry, you just got Leo'd.

Speaker 1 Leo.

Speaker 1 Now, obviously this story is a lot of fun, but as many of you have probably guessed, it is almost certainly a historical myth.

Speaker 1 But what's fascinating is that it's a myth that comes from the Arabic sources.

Speaker 1 This tale can be found in the history of Al-Tabari that I mentioned earlier in the episode, but the most detailed version comes from the Arabic chronicle known as the Kitab al-Uyan, which was written in the late 11th century.

Speaker 1 That's a solid 350 years after the siege of 717.

Speaker 1 It does not appear in Theophanes' Chronicle or any other Roman source.

Speaker 1 So, you might be wondering, why would an Arabic historian include a story that is so unflattering to Maslama and the Muslims?

Speaker 1 Well, the best guess is that the Muslim chroniclers were trying to portray Maslama's inability to take Constantinople as being the result of pure trickery.

Speaker 1 The idea is that the Muslims didn't lose a fair fight. Leo III cheated them.

Speaker 1 In all of the Arabic sources, Maslama is presented as being chivalrous to a fault. He's so honest that he almost can't conceive of someone as tricky and duplicitous as Leo.

Speaker 1 Leo, by contrast, is presented as a devilish liar, the stereotype of the tricky Greek exaggerated to demonic proportions.

Speaker 1 In the Kitab al-Uyon, there's even a quote, allegedly from Leo, where he boasts that, quote, if Maslama had been a woman, I would have chosen to seduce her.

Speaker 1 I would have done it, and he would have never refused me anything that I desired of him, end quote. This is presented as supervillain talk.

Speaker 1 Remember, if you're rooting for Maslama, then Leo's deceptions seem very slimy.

Speaker 1 So if you follow the logic here, the Romans only won because they cheated, and Maslama's only failure was that he was too honest.

Speaker 1 By contrast, all Theophanes the Confessor tells us is that winter that year was very hard, and it took its toll on Maslama's army, which, quote, lost a multitude of horses, camels, and other animals, end quote.

Speaker 1 In that time, another key event took place that would ultimately have a huge effect on the future of the siege.

Speaker 1 In the fall, either in September or October of 717, the Umayyad Caliph Suleiman died in Damascus.

Speaker 1 Now, obviously, Suleiman was one of the driving forces behind this entire attack on Constantinople. He was the guy who pledged to exhaust his entire empire's resources to take the city.

Speaker 1

Now, it's sometimes incorrectly assumed that the death of Suleiman ended the siege. This is not true.

The siege continued for nearly a year after Suleiman's death.

Speaker 1 The new caliph in Damascus was a man named Umar, and he did not immediately call off the siege and recall Maslama. The Umayyads were hardly beaten as 717 became 718.

Speaker 1 It was still highly likely that Maslama would be victorious and the city would fall.

Speaker 1 But it is true that the Caliph Umar was less enthusiastic about this whole adventure and was certainly not going to bankrupt the empire to take the city.

Speaker 1 All this meant was that Maslama needed to show that in 718 he was making some progress.

Speaker 1 For his part, the new caliph Umar did his best to help his general in the field.

Speaker 1 He sent two fresh fleets to resupply the army and a fresh land force was sent through Anatolia, raiding and disrupting Roman life as they went.

Speaker 1 However, one of the Roman armies still operating in Anatolia was able to successfully ambush the new land force and, according to Theophanes, quote, broke it into pieces, end quote, and forced the Muslims to withdraw.

Speaker 1 The new fleet was another story altogether. We're told that most of this new fleet was from Egypt and was mostly manned by Egyptian Christians.

Speaker 1 Upon arriving in the Sea of Marmora, the relief fleet kept its distance from Constantinople and hid from the sight of the Romans in protected bays on the Asian coast where the Bosphorus meets the Sea of Marmora.

Speaker 1 But apparently, upon seeing Constantinople, many of the Egyptian sailors, feeling sympathy for their fellow Christians, decided to desert their ships en masse.

Speaker 1 The deserters made their way to Constantinople, where they revealed the locations of these anchored fleets to the Romans.

Speaker 1 Knowing that these relief fleets were now dangerously understaffed, the Romans moved quickly against them and once again unleashed liquid fire.

Speaker 1 Theophanes tells us that this time both of the relief fleets were, quote, sunk on the spot, end quote, which honestly seems unlikely.

Speaker 1 But the attack was clearly devastating enough that it loosened the blockade even further, giving Roman fishermen even more room to roam.

Speaker 1 More importantly, this successful Roman naval attack meant that much-needed supplies carried by the relief fleet never got to Maslama's main force who were besieging the Theodosian walls.

Speaker 1 As a result, Theophanes tells us, quote, The Arabs suffered from severe famine, so that they ate all their dead animals, namely horses, asses, and camels.

Speaker 1

It is said they even cooked in ovens and ate dead men and their own dung, which they leavened. End quote.

Oh, oh, you know, things are bad when you're eating poop bread.

Speaker 1 Now, of course, the words, it is said, are doing a lot of heavy lifting for Theophanes in that passage.

Speaker 1 When one of these early medieval sources hints that a story might just be a legend, it almost certainly is a legend.

Speaker 1 Still, it's probably safe to assume that Maslama's main force was running low on supplies and was weakened by poor nutrition.

Speaker 1 Then Theophanes tells us that at the Arab army's lowest moment, the Bulgars appeared. The horsemen swept down on the exhausted besieging army and allegedly killed 22,000 Arab soldiers.

Speaker 1 The deal that Leo had struck with his sometime Bulgar enemies had paid off. Now, to be clear, other sources tell a different tale about this Bulgar attack.

Speaker 1 A Syriac chronicle tells us that this was just another attack that happened when some Muslim raiders headed too far north looking for supplies.

Speaker 1 So, it's possible that this Bulgar attack was a devastating last straw, or it was just another in a series of raids that at this point the Arabs could ill afford.

Speaker 1 Either way, by August of 718, Maslama's force was cooked.

Speaker 1 Their supplies were all but exhausted, and the Romans had just expanded their fishing grounds.

Speaker 1 Maslama's army had been seriously diminished, and what remained of his fleet were so spooked by Greek fire that they all but refused to tighten their blockade.

Speaker 1 On top of all of that, the new caliph Umar had lost any enthusiasm he may have had for his predecessor's grand military adventure.

Speaker 1 So, the Arabs picked up stakes and left.

Speaker 1 But Theophanes being Theophanes tells us, of course, that God then decided to sink the rest of the fleet in a terrible storm.

Speaker 1 Because this is what always happens to invading Arab fleets, according to Theophanes.

Speaker 1 Except this time he adds the detail that a volcanic eruption caused, quote, a fiery hail to fall on them and brought the sea water to a boil. End quote.

Speaker 1 In the end, he tells us that only five ships of the original 1800 made it back to Syria.

Speaker 1 Now,

Speaker 1 this might have happened. The volcanic eruption seems specific enough that it could be true.

Speaker 1 But Theophanes always has God destroying fleets with a storm.

Speaker 1 This is also one of the details that makes experts think that the whole story of the first siege is just a truncated version version of the second siege, just set further back in time.

Speaker 1 The fact that the first siege is said to have ended after the Romans unleashed Greek fire and then God swooped in with a fleet-wrecking storm seems like a real coincidence.

Speaker 1 In the end, this defeat at Constantinople was a costly disappointment for the Caliphate.

Speaker 1 In later centuries, a face-saving legend would develop that before Maslama departed, Leo recognized his greatness.

Speaker 1 According to the Kitab al-Uyan, the siege finally ended when Leo let Maslama enter the city with 30 riders.

Speaker 1 They were allowed to stand in the Hagia Sophia, the great cathedral at the heart of the city, where Emperor Leo publicly venerated the great Muslim general.

Speaker 1 Satisfied, Maslama then mercifully called off the siege.

Speaker 1 Now, this one is an obvious myth that's only found in that one Arabic source. It isn't found in the history of al-Tabari, let alone any of the Roman sources.

Speaker 1 The evidence tells us that the 717 siege of Constantinople was an embarrassing debacle for the Caliphate and a triumph for Leo III and the Romans.

Speaker 1 The Roman Empire would live to fight another day because, my God, the Roman Empire just simply refused to die.

Speaker 1 Many historians also believe that this was a turning point for the Umayyad Caliphate.

Speaker 1 The Caliph Umar would be far less expansion-minded than his predecessor, and instead concentrated most of his time as caliph on trying to hold together a giant empire empire that was filled with internal divisions.

Speaker 1 Within a few decades, these divisions would tear the Umayyad Caliphate apart. The new Abbasid Caliphate would come to power and would move the capital away from Damascus and to Baghdad.

Speaker 1 This instigated what many historians have called Islam's cultural golden age, as Baghdad became a center of art and learning.

Speaker 1 This move of the capital to Baghdad reflected the new priorities of the Abbasid Caliphate.

Speaker 1 Capturing Constantinople was simply never as important for the Abbasid Caliphs as it had been for the Umayyads.

Speaker 1 From Baghdad, the Roman capital seemed far away, and frankly, more trouble than it was worth.

Speaker 1 And so it was that the fall of the city was pushed into a mythological future and became associated with the end of days.

Speaker 1 Muslims would not besiege Constantinople again until the rise of the Ottoman Turks some 600 years later.

Speaker 1 But that doesn't mean that Constantinople was just left alone for those centuries.

Speaker 1 You see, one of the reasons I've never liked the metanarrative that the Romans saved the West by resisting the Umayyad siege of Constantinople, is that up until the coming of the Ottoman Turks, it was people who we often perceive as Westerners who posed a greater threat to Constantinople than anyone else.

Speaker 1 In the centuries after 717, Constantinople was besieged by the Slavs, the Rus, and the Bulgars.

Speaker 1 The medieval Bulgarian Empire besieged the city three times between 913 and 923, and they were fellow Orthodox Christians by that time.

Speaker 1 But the most devastating siege came in 1204.

Speaker 1 In that year, for the first time in centuries, the Theodosian walls failed to protect the city. Constantinople was brutally sacked, and much of its material wealth was carried away.

Speaker 1 To this day, treasures looted from Constantinople in 1204 decorate the cities of those who led the siege. These attackers were not Muslims.

Speaker 1 They were crusaders taking part in the notorious Fourth Crusade.

Speaker 1 Christians from Italy, France, and the German-speaking parts of Europe. You know, the West.

Speaker 1 So if you're going to insist that the Byzantines saved the West in 717,

Speaker 1 you also have to admit that the West repaid them with death, destruction, and the looting of a millennia's worth of heritage just a few centuries later.

Speaker 1 Drawing a straight line from the Roman victory in 717 to the European Enlightenment some 1,000 years later is ridiculous and skips over some fairly important parts of the story, like that part when Western European Christians very nearly ended the Roman Empire in 1204.

Speaker 1 But the Roman Empire somehow recovered from that one as well.

Speaker 1 Even when being the emperor of the Romans meant reigning over the ruins of a once great empire, you could always find someone who would strap on a gold nose and call themselves Caesar.

Speaker 1 Okay,

Speaker 1

that's all for this week. Join us again in two weeks' time when we will explore an all-new historical myth.

I hope you enjoyed that trilogy.

Speaker 1 Man, I love going deep on stories like this, so I hope you dug it.

Speaker 1 Before we go this week, as always, I need to give some very special shout outs. Big ups to

Speaker 1 Depon Richter

Speaker 1 to Sokka

Speaker 1 to Steph the Chef

Speaker 1 to Rob Delio

Speaker 1 to Graham Gilbert to Sean Thornton to Brad Orego

Speaker 1 to

Speaker 1 Gian de Morial

Speaker 1 to

Speaker 1

Aloysius Vander Tvist. Oh, there's a name.

Thank you. Big ups to Philip Goudemi, to David Goth,

Speaker 1 to Adrian Flores,

Speaker 1 to Dan, and to Brian Court.

Speaker 1 All of these folks are now pledging $5

Speaker 1

or more on Patreon. So you know what that means.

They are beautiful human beings. Thank you, thank you, thank you to everyone who supports on Patreon at all levels.

Speaker 1 Thank you to everyone who writes nice reviews of the show, gives us five stars. And thank you to everyone who recommends this show to their friends.

Speaker 1

Word of mouth might be old-fashioned, but I honestly think it's the best way to spread the word. There's something about the in-person recommendation.

Know what I mean?

Speaker 1

If you ever want to get in touch with me, please send me an email. Email is probably the best way to get me, to be honest.

Find me at ourfakehistory at gmail.com.

Speaker 1

You can also hit me up on Facebook, facebook.com slash our fake history. You can find me on Blue Sky.

I'm actually really enjoying Blue Sky. I feel like our community is sort of crackling there.

Speaker 1

So look for Our Fake History on Blue Sky. I'm still on X at OurFake History.

I'm on Instagram at OurFake History. I'm on TikTok at OurFake History.

Speaker 1 And of course, I still have the Our Fake History YouTube channel. Go to YouTube and just search for Our Fake History.

Speaker 1 As always, the theme music for the show comes to us from Dirty Church. Check out more from Dirty Church at dirtychurch.bandcamp.com.

Speaker 1 All the other music you heard on the show today was written and recorded by me.

Speaker 1 My name is Sebastian Major, and remember, just because it didn't happen doesn't mean it isn't real.

Speaker 1 One, two, three, four,

Speaker 1 There's nothing better than a one-place life.