Episode #215 - Edgar Allan Poe: Hoax Master?

See Privacy Policy at https://art19.com/privacy and California Privacy Notice at https://art19.com/privacy#do-not-sell-my-info.

Press play and read along

Transcript

Speaker 1 Hey everyone, Sebastian here. Just wanted to let you know that I will once again be participating in this year's Intelligent Speech Conference.

Speaker 1 Deception, lies, fakery, fraudulence, and forgery is what they have on the docket for Intelligent Speech 2025.

Speaker 1 So, obviously, I've got to be there. For those that don't know, Intelligent Speech is an online conference that highlights the best in history podcasting.

Speaker 1 Intelligent Speech 2025 deception will be taking place on the 8th of February 2025. So if you want tickets, go to intelligent speechonline.com right now and get yourself to the conference.

Speaker 1 Let's start today with a fun fun little trivia question.

Speaker 1 What do American founding father Benjamin Franklin, the godfather of the computer Charles Babbage, and Emperor of the French Napoleon Bonaparte all have in common?

Speaker 1 If you answered they were all humiliated by a robot, you would be correct.

Speaker 1 Well, humiliated might be too harsh a word, and even the word robot is a touch imprecise in this context. Let me rephrase.

Speaker 1 All three of these epoch-defining luminaries were defeated by the same chess-playing automaton.

Speaker 1 Honestly, humiliated by a robot still feels better, but hey, let's not get hung up on this.

Speaker 1 The point is that all three of these men, who have been variously praised as geniuses, lost a game of chess to what appeared to be a clockwork machine.

Speaker 1 Babbage technically lost two games to the contraption. And by the way, these fellows weren't slouches when it came to playing chess.

Speaker 1 In particular, Benjamin Franklin was a noted enthusiast of the game.

Speaker 1 In 1786, he even penned an essay titled The Morals of Chess, where he argued, quote, The game of chess is not merely an idle amusement.

Speaker 1 Several very valuable qualities of the mind, useful in the course of human life, are to be acquired or strengthened by it. ⁇ End quote.

Speaker 1 Franklin played chess almost daily and has even been inducted into the Chess Hall of Fame.

Speaker 1 So you can imagine his shock when he was bested by what he had been told was the world's first thinking machine.

Speaker 1 Now, I'm sure some of you are wondering, how was this possible?

Speaker 1 How was it that an artificial intelligence sophisticated enough to play chess and defeat capable human opponents existed at the turn of the 1800s?

Speaker 1 Well, perhaps we should start at the beginning.

Speaker 1 In 1769, at the court of Empress Maria Theresa in Vienna, a group of assembled dignitaries were treated to a demonstration by a French inventor named Pelletier.

Speaker 1 The showcase was pitched as an exhibition of, quote, certain experiments of magnetism, end quote. But the whole affair felt more like a magic show than a scientific lecture.

Speaker 1 Pelletier wowed the crowd by producing remarkable levitation effects that he explained were being produced using powerful magnets.

Speaker 1 The Empress and her entourage were all thoroughly impressed by this, except for one Hungarian aristocrat who found the whole thing a little pedestrian.

Speaker 1 This was Farkas de Kemplin, also known as Wolfgang Kemplin, an engineer and inventor connected to the Austrian court.

Speaker 1 After seeing Pelletier's magnet show, Kemplin declared to the Empress that he could invent, quote, a piece of mechanism which should produce effects far more surprising and unaccountable than those which she then witnessed, end quote.

Speaker 1 The Empress told him that she would very much like to see that.

Speaker 1 And with that, the gauntlet was thrown down. So Kemplin got to work.

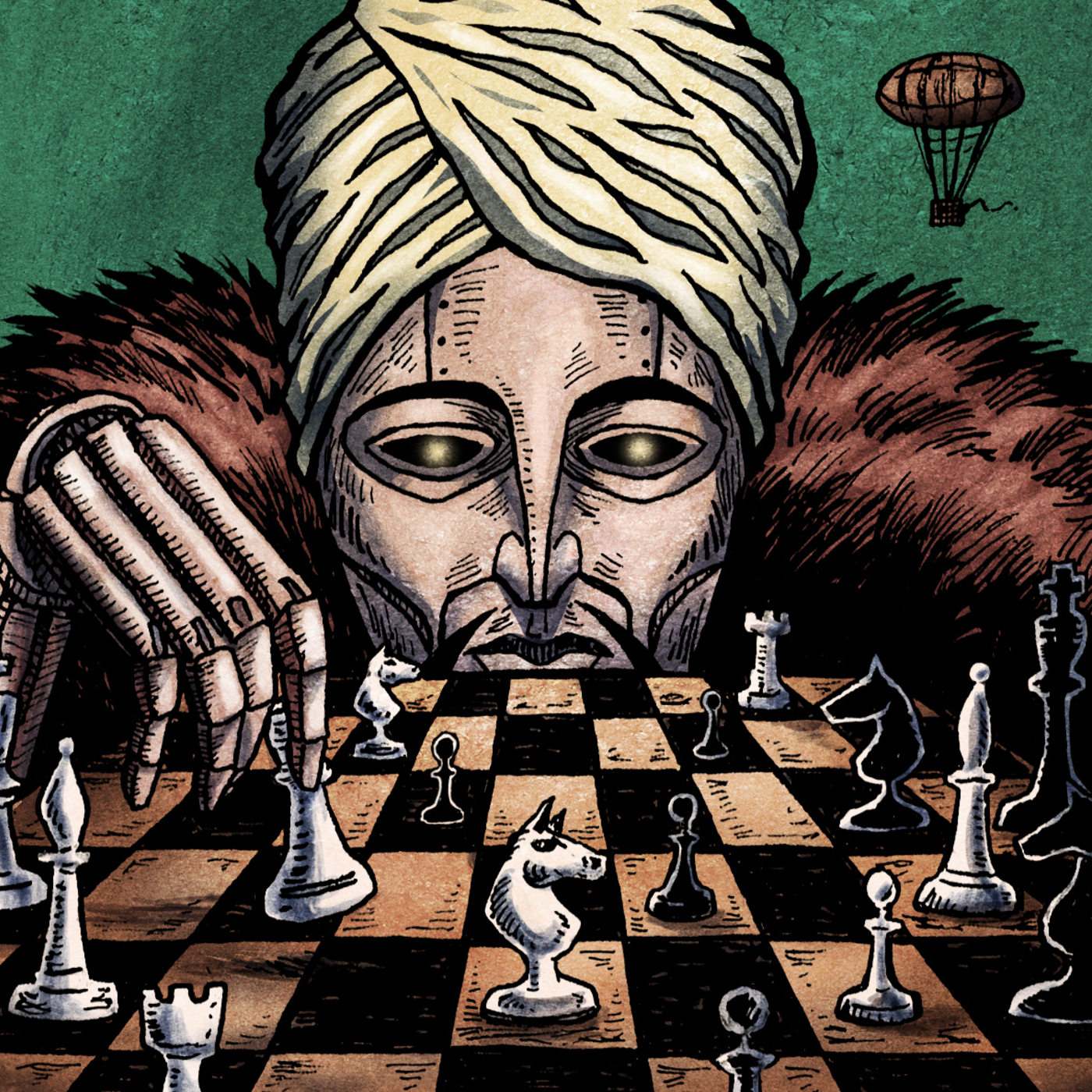

Speaker 1 A year later, the inventor was back at court with a remarkable new device, known simply as the Turk.

Speaker 1 The Turk was a human-sized automaton, that is, a clockwork machine, dressed up as though he was an Ottoman man of leisure.

Speaker 1 He wore a turban and a bespoke silk robe. He had a well-coifed mustache and even smoked a long pipe.

Speaker 1 He was connected to a large cabinet, the inside of which contained gears and machinery, but the top of which acted as a playing surface.

Speaker 1 On the surface was a chessboard and all the pieces needed for a game.

Speaker 1 When Kemplin presented this device, he began with a thorough examination of the cabinet to assure the crowd that no trickery was afoot.

Speaker 1 The cabinet had two compartments, each of which could be seen by opening a small door. When the door on stage right was opened, the audience could see the dizzying array of clockwork gears inside.

Speaker 1 A door on the reverse side of the cabinet was opened and a candle was shined through to show that nothing was hiding behind the gears.

Speaker 1 That door was then closed, and the door on stage left was then opened, which revealed that that part of the cabinet was largely empty save for a few metal rods running the Turk.

Speaker 1 The doors were then closed, the chess pieces were taken out from a drawer at the bottom of the cabinet, the game was set, and Kemplin issued his challenge.

Speaker 1 If there was anyone in the crowd who believed that they could beat the Turk in a game of chess, then they should come forward right away.

Speaker 1 Challengers would come up and sit across from their turbaned opponent and would make their best attempt to win.

Speaker 1 After being wound up with a large crank, the Turk could use a mechanical arm to move the pieces on the board much like a human player.

Speaker 1 Amazingly, he always reached for the right piece and moved it according to the rules. What's more, the Turk was good.

Speaker 1 Not only could this device perceive the board and move the pieces, it was clearly well-versed in chess strategy.

Speaker 1 It almost never lost.

Speaker 1 Kemplin would sometimes encourage his human players to attempt illegal moves to test the machine.

Speaker 1 If the Turk's opponent tried to move a knight like it was a bishop, the machine would comically shake his head, no, and wave his hand.

Speaker 1 Needless to say, the Turk was an immediate sensation. After making a rapturous debut at the Austrian court, Kemplin was soon compelled to take his show on the road.

Speaker 1 Over the course of the next few years, the Turk made its way around Europe, touring mostly in the German-speaking parts of the continent, but also making well-publicized stops in Amsterdam, London, Versailles, and Paris, where it played its fateful match with Benjamin Franklin.

Speaker 1 Then, in 1804, Kemplin passed away, and the Turk was purchased by a Bavarian musician and automaton enthusiast, Johann Maltzl.

Speaker 1 Maltzel was even more of a showman than Kemplin, so he made some improvements to the Turk to make it even more entertaining.

Speaker 1 The automaton was given moving eyes and the ability to do funny little celebration dances with its head when it won. And most impressively, the Turk was given the ability to speak.

Speaker 1 Now, when the machine checked its opponent, it could actually say the word eche in French using a mechanical voice box.

Speaker 1 With the new and improved Turk, Maltzel set out on a more ambitious tour to fully capitalize on the remarkable machine.

Speaker 1 It was now some thirty years after the Turk had been originally invented, and it was still widely considered the world's most sophisticated automaton.

Speaker 1 It was this version of the Turk that faced off against Napoleon in 1809.

Speaker 1 Then, in 1826, after extensive tours of Europe and the UK, Maltzel brought the Turk to America, where it enjoyed a solid decade of storied performances.

Speaker 1 But the longer the Turk performed, the more fierce the speculation became about how it worked.

Speaker 1 While some were convinced that the Turk was everything it purported to be, a sophisticated piece of machinery and the world's first artificial intelligence, others weren't so sure.

Speaker 1 Some believed that the device was so unnatural that it had to be demonic or animated by some black magic. After the Turk made its debut in Boston in 1826, the local poet Hannah F.

Speaker 1 Gould penned these lines, quote,

Speaker 1 When first I viewed thine awful face, rising above that ample case, which gives thy cloven foot a place, thy double shoe, I marveled whether I had seen old Nick himself or a machine or something fixed midway between.

Speaker 1 End quote.

Speaker 1 For those that don't know, old Nick was a nickname for Satan himself.

Speaker 1 Indeed, the machine seemed too good to be true. Many more scientific observers believed that the secret of the machine was not some dark sorcery, but a clever bit of stage magic.

Speaker 1 After all, the presentation of the Turk was very much like a magic show, complete with a mysterious cabinet, and a moment where the magician ostentatiously showed the crowd that he had nothing up his sleeves.

Speaker 1 The only problem was that for decades no one could figure out exactly how the trick was accomplished. Even the skeptical had to admit that even if it was an illusion, the illusion was revolutionary.

Speaker 1 An Austrian admirer of the Turk, Carl Gottlieb De Windich, summed it up by saying, quote, Tis a deception, granted, but such a one as does honor to human nature, a deception more beautiful, more surprising, more astonishing than any to be met with in the different accounts of mathematical recreations.

Speaker 1 End quote.

Speaker 1 The Turk enjoyed a remarkable 68-year run as a touring attraction before Maltzel tragically died at sea in 1838 during an Atlantic crossing.

Speaker 1 After that, the automaton fell into the totally unprepared hands of the ship's captain.

Speaker 1 And by the way, isn't it kind of a trip that there was a moment in history when robots were being transported across the ocean in sailboats? Man, that's why I love this stuff. Anyway,

Speaker 1 in that time, those 68 years of touring, no one correctly guessed the secret of the Turk.

Speaker 1 But a couple people got close.

Speaker 1 The person who often gets the most credit for publicly debunking the Turk is none other than Edgar Allan Poe.

Speaker 1 Yes, the celebrated American author, poet, and literary innovator, Edgar Allan Poe.

Speaker 1 He was relatively unknown in 1836 when he published an essay arguing that there was no possible way that the Turk was a, quote, pure machine.

Speaker 1 At the time, Poe was an editor and contributor to the literary magazine known as the Southern Literary Messenger.

Speaker 1 After attending a number of performances of the Turk, Poe reasoned that this automaton was not, in fact, a machine pretending to be a human. It was a human pretending to be a machine.

Speaker 1 In the essay, Poe laid out a number of arguments meant to demonstrate that the movements of the Turk were being directed by a human mind.

Speaker 1 Now, some of Poe's arguments have aged better than others, but perhaps his most trenchant insight was that the action of the Turk's robotic arm was more stilted, halting, and machine-like than most automatons.

Speaker 1 The opening act of Maltzel's show featured automatons that Poe described as able to, quote, copy the motions and peculiarities of life with the most wonderful exactitude, end quote.

Speaker 1 Malzel knew how to make wind-up clockwork devices that beautifully mimicked the movements of humans and animals. Why not make the Turk just as smooth?

Speaker 1 Poe argued that if the Turk was as smooth as Maltzel's other automatons, it would inadvertently give away the secret.

Speaker 1 If it moved like a human, everyone would guess that there was, in fact, a human inside the Turk, operating it like a puppet.

Speaker 1 Or, as Poe put it, quote, the awkward and rectangular maneuvers convey the idea of a pure and unaided mechanism, end quote. Being clunky was a misdirection, but for Poe, it was a tell.

Speaker 1 It seemed strange that an automaton sophisticated enough to play chess as well as the Turk would have such unsophisticated arm movements.

Speaker 1 Poe's conclusion was that there was a living, breathing person inside the Turk mannequin, playing chess normally, but acting like an automaton.

Speaker 1 Poe's essay turned out to be an early success for the author that inspired responses from other newspapers and literary magazines like the Norfolk Herald, the Baltimore Gazette, the Winchester Virginian, and the New Yorker.

Speaker 1 While Poe's essay certainly didn't end the career of the Turk, it coincided with a waning of American interest in the device.

Speaker 1 And sure enough, 21 years later, Poe's assessment of the machine would be proven mostly correct.

Speaker 1 In 1857, long after the Turk stopped touring, its owner decided that it was time to reveal the secret of the machine.

Speaker 1 Edgar Allan Poe had correctly guessed that a secret human operator had been puppeteering the Turk. It turned out that this puppeteer was usually a chess grandmaster.

Speaker 1 However, Poe had not guessed the ingenious way that the puppet operated.

Speaker 1 The chessmaster puppeteer was not hidden inside the Turk mannequin, but was instead hidden inside the large chest.

Speaker 1 The chest was designed like a magician's prop. The puppeteer could slide between the compartments to hide from the audience when the inner workings were being displayed.

Speaker 1 When the doors were closed, the chess master could sit comfortably with his legs stretched out in the chest.

Speaker 1 He was able to see which moves were being made because the chess pieces above him were secretly magnetized.

Speaker 1 When a piece was moved, small magnets on the underside of the chessboard would be attracted to it and would tell the puppeteer where his opponent had moved.

Speaker 1 The puppeteer then recreated the move on a small pegboard chessboard in front of him. Then, the truly brilliant part of it.

Speaker 1 The arm of the Turk, while not a clockwork machine, was a fairly sophisticated contraption.

Speaker 1 It was based on a device known as a pantagram, which was used by engineers and artists to create enlarged versions of drawings or blueprints.

Speaker 1 By moving the controlling end of the pantagram over the little pegboard inside the case, the arm of the mannequin would then move to the corresponding spot on the real chessboard.

Speaker 1 The operator could then turn a lever, which would allow the Turk to grasp a piece and then release it at the correct time.

Speaker 1 In the end, all of those people who were defeated by the Turk were, in actual fact, defeated by a chess master tutored in the arts of puppetry.

Speaker 1 Poe had been mostly right while being wrong about the specifics.

Speaker 1 Still, his debunking got him some much-needed attention.

Speaker 1 The powers of observation and deductive reasoning that Poe demonstrated in the article would eventually become defining features of his much-loved detective stories.

Speaker 1 But I think that there was a deeper reason that Edgar Allan Poe became so fixated on the chess-playing automaton.

Speaker 1 The performances of the Turk combined two of Poe's most enduring interests, the frontiers of science and elaborate hoaxes.

Speaker 1 You see, Poe was not just a debunker of flim flam, he was a noted flim flam artist in his own right.

Speaker 1 Over the course of his literary career, Edgar Allan Poe was behind at least six hoaxes, fake news stories passed off as strange but true occurrences.

Speaker 1 Interestingly, all of the authors' hoaxes dealt with new and amazing scientific achievements and used a style of deception similar to the chess-playing automaton.

Speaker 1 The Turk did not pretend to be magic, only an amazing application of the newest and best engineering.

Speaker 1 But in the 1800s, science could often appear magical and was often presented to the public using the beats of a magic show.

Speaker 1 Edgar Allan Poe chose to play in this blurry space when real discoveries seemed unbelievable and unbelievable claims could seem real.

Speaker 1 Was Edgar Allan Poe just another 19th century con man looking to make a dime off a sensational story?

Speaker 1 Or was he secretly trying to elevate the American reading public and engender a new type of critical thought.

Speaker 1 Let's get into it today on our fake history.

Speaker 1 One, two, three, five.

Speaker 1 Episode number 215, Edgar Allan Poe, Oaksmaster.

Speaker 1 Hello, and welcome to Our Fake History.

Speaker 1 My name is Sebastian Major, and this is the podcast where we explore historical myths and try to determine what's fact, what's fiction, and what is such a good story that it simply must be told.

Speaker 1 Before we get going this week, I just want to remind everyone that an ad-free version of this podcast is available through Patreon.

Speaker 1 Just go to patreon.com/slash our fake history to get access to an ad-free feed and a long list of other fun extras.

Speaker 1 Speaking of extras, this is the last call for patrons to vote on the topic for the next patrons-only extra episode.

Speaker 1 I'm going to be announcing the winner of that poll on episode 216, which will be dropping two weeks from this release. So, you will have from now until then to cast your vote.

Speaker 1 Patrons at all levels, that includes the $1 patrons, get to vote and will get to hear the completed episode. Our Fake History might be the last podcast on the planet with a $1 Patreon tier.

Speaker 1 So, come on, get in on the fun and help choose the topic for the next extra.

Speaker 1 This week, we are returning to one of this podcast's most fun subgenres.

Speaker 1 As you know, I usually explore fake history, that is, historical myths and misconceptions. But every now and then, I like to flip the script a little bit and examine one of history's greatest fakes.

Speaker 1 So you can imagine my delight when I learned that the famous American author Edgar Allan Poe had been behind a number of the 19th century's best-remembered newspaper hoaxes.

Speaker 1 As we have explored before on this podcast, the 19th century was a particularly fertile time for hoaxers, snake oil salesmen, and humbug artists, especially in the United States.

Speaker 1 Now, the question is why?

Speaker 1 Well, as any longtime fan of this podcast can tell you, deception, spin, and narrative building are as old as the human experience.

Speaker 1 The 1800s certainly do not have a monopoly on flim flam, but the 1800s saw a convergence of historical forces that made hoaxing easier and more profitable.

Speaker 1 One of these forces was the rapid growth of print media.

Speaker 1 Newspapers, magazines, and periodicals certainly predated the 19th century, century, but the mechanization of the printing process meant that in the 1800s there was an explosion of new media.

Speaker 1 Printed material was cheaper than ever, which meant that more could be printed. This gave newspapers, journals, and dime store novels a type of reach that they'd never seen before.

Speaker 1 A story, be it real or spurious, could spread in a way that it simply could not have done in earlier eras.

Speaker 1 Another important part of the puzzle had to do with the remarkable scientific breakthroughs and technological advances that defined the period.

Speaker 1 In the 1800s, science was actively challenging long-accepted truths about existence. Geologists were upending long-held dogmas about the age of the Earth.

Speaker 1 Astronomers were looking ever deeper into space, discovering new planets and calculating the distance of faraway stars.

Speaker 1 Even the revered place of humanity in creation was being challenged by the new theories of natural selection and evolution.

Speaker 1 It was not uncommon in the mid-1800s to read that something that had been believed to be true for centuries was now deeply uncertain.

Speaker 1 On top of that, new, previously unimaginable technologies were being introduced every year.

Speaker 1 Just imagine how magical electricity and electrical devices would have seemed to people who had not experienced them before.

Speaker 1 An invisible force in nature was literally being harnessed to light homes and run motors. That's bananas.

Speaker 1 Paleontologists were discovering extinct dinosaurs, and chemists were making medicines that could cure or prevent previously fatal diseases.

Speaker 1 Even surgery, which had previously been a nightmarish experience, could by the 1800s be performed nearly painlessly with the aid of helpful chemicals.

Speaker 1 The truth of science in the mid-19th century was, frankly, unbelievable.

Speaker 1 So, a lie about science or the frontiers of technology, even an extravagant lie, didn't seem beyond the pale. Put that lie in print, and before you know it, you have a full-on hoax on your hands.

Speaker 1 By the 1830s in America, hoaxing and scientific quackery were all over American newspapers. At the time, the famous American physicist Joseph Henry complained, quote,

Speaker 1

in this country, our newspapers are filled with puffs of quackery. Every man who can burn phosphorus and oxygen and exhibit a few experiments to a class of young ladies is called a man of science.

⁇

Speaker 1 In other words, real scientists were getting fed up with the fakes.

Speaker 1 Now, some of these hoaxes were frivolous, pranks meant to have a short shelf life aiming only for laughs, while others were exploitative.

Speaker 1 Con men could make a quick buck peddling bogus medicines or exhibiting wondrous but fake machines. The humbugs of the showman P.T.

Speaker 1 Barnum famously walked the line between these two types of hoaxes, being that they were usually harmless pranks that still managed to line the pockets of America's lovable liar.

Speaker 1 But there was also a third type of hoax, the satirical hoax, the hoax that was meant to deceive, but in the uncovering was ultimately meant to teach the public something about critical thinking.

Speaker 1 There at the intersection of American science, American literature, fiction, and non-fiction was Edgar Allan Poe.

Speaker 1 Now, if you've been educated in North America, there's almost no way that you haven't heard of Edgar Allan Poe.

Speaker 1

In my part of the world, it's very hard to make it out of high school without having read at least one Poe short story. He's widely recognized as one of the greatest American authors.

Period.

Speaker 1 He was a pioneer in the genres of detective fiction, horror, and sci-fi.

Speaker 1 And the author of a poem so enduring that the Simpsons used it more or less unchanged as part of one of their classic Treehouse of Horror Halloween episodes. Quoth the Raven.

Speaker 1

Beat my short spark, stop it. He says never more, and that's all he'll ever say.

Okay, okay.

Speaker 1 Well, I guess they changed it a little bit. The point is that Edgar Allan Poe is one of those literary figures who's had no shortage of accolades.

Speaker 1 But a less explored aspect of Poe's life is his hoaxing career. Between the years 1835 and 1849, he was behind six hoaxes, which appeared in various newspapers and American literary magazines.

Speaker 1 Some of these hoaxes were entertaining, but didn't manage to fool anyone, while others caused a legitimate stir.

Speaker 1 What I'm interested in is why some of these hoaxes worked and some did not.

Speaker 1 So today we're going to focus on two of Poe's hoax attempts, one that was an amusing flop and another that seriously hoodwinked some folks.

Speaker 1 By looking closely at these scientific hoaxes, I'm hoping we can find the secret sauce that makes a lie believable.

Speaker 1 Now this episode is not going to be a comprehensive biography of Edgar Allan Poe, even though he is a genuinely interesting dude with a notably mysterious death.

Speaker 1 But that story will have to wait for another day.

Speaker 1 Today, we're going to keep our focus trained on just two of Edgar Allan Poe's hoaxes to see what they can tell us about the slippery nature of truth, the mechanics of a successful lie, and the American public's relationship with the frontiers of science in the mid-1800s.

Speaker 1 Okay, let's get into it.

Speaker 2 Trying to lose weight? It's time to try HERS. At forhears.com/slash for you, you can access affordable doctor-trusted weight loss treatments tailored just for you.

Speaker 2 These include oral medication kits or compounded GLP-1 injections. Through HERS, pricing for oral medication kits start at just $69 a month for a 10-month plan when paid in full up front.

Speaker 2 No hidden fees, no membership fees. You shouldn't have to go out of your way to feel like yourself.

Speaker 2 HERS brings expert care straight to you with 100% online access to personalized treatment plans that put your goals first. Reach your weight loss goals with help through HERS.

Speaker 2

Get started at forhers.com slash for you to access affordable doctor-trusted weight loss plans. That's forhers.com slash for you.

F-O-R-H-E-R-S.com slash for you. Paid for by him and hers health.

Speaker 2

Weight loss by hers is not available everywhere. Compounded products are not FDA approved or verified for safety, effectiveness, or quality.

Prescription required. Restrictions at forhears.com.

Apply.

Speaker 1 The life of young Edgar Poe was nothing if not tumultuous. His biological father abandoned his mother around the time of his birth, and his mother tragically died a year later.

Speaker 1 Edgar was taken in by the Allen family. They changed his name to Edgar Allen Poe, but never formally adopted the boy.

Speaker 1 The Allens were a modestly wealthy family from Richmond, Virginia, although in Poe's youth they relocated to the UK, where young Edgar completed most of his education, first in Scotland and then in posh boarding schools in Chelsea.

Speaker 1 The young Poe showed promise as a student, but his attempts at post-secondary education were a bit of a disaster.

Speaker 1 After returning to the United States, he was admitted to Virginia University, but a combination of a tight budget imposed on him by his foster father and a bad gambling habit meant that Poe washed out after his first year.

Speaker 1 This eventually led to a brief stint as a cadet at West Point Military Academy. But Poe didn't fare much better there.

Speaker 1 After growing restless, Poe found the fastest way to be released from his military service. Purposefully neglect duty, get court-martialed, and then dishonorably discharged.

Speaker 1 But during all of this educational tumult, Poe started writing poetry and dreaming about publishing.

Speaker 1 His first collection of poetry was actually published with the help of donations from his West Point classmates, who enjoyed the biting poems he would sometimes write about their instructors.

Speaker 1 By the mid-1830s, Poe was published and was doing his utmost to make his life as a writer, bouncing between Baltimore and Richmond before settling in Philadelphia and then eventually New York City.

Speaker 1 Edgar Allan Poe is generally regarded as one of the first Americans to make his living purely as a writer. However, in the 1830s and the 1840s, this meant that he was just scraping by.

Speaker 1 As such, this meant engaging in all sorts of writing, from his more high-minded poetical pursuits to bits of frivolous fiction and pulpy stories for cheap penny papers.

Speaker 1 Poe's hoax stories came out of a growing demand for sensational tales that could move papers at an increasingly competitive newsstand.

Speaker 1 In the 1830s, papers would sometimes publish hoaxes, even obvious hoaxes, just to drum up some controversy and get eyes on their publication.

Speaker 1 The idea was that readers would be encouraged to judge for themselves if the story was fact or fiction. Then a few days later, the paper would usually come clean, but not always.

Speaker 1 Edgar Allan Poe's newspaper hoaxes fit right in with that emerging genre in the 1830s.

Speaker 1 But some Poe scholars like Linda Walsh and John Tresh have argued that the author was aspiring to something greater than many of his contemporaries.

Speaker 1 They believe that Poe was using these hoaxes to communicate a deeper scientific, spiritual, and aesthetic philosophy. The hope was that he might even win some people over to this new way of thinking.

Speaker 1 Now, despite the fact that Poe's secondary education had been patchy and filled with disruptions, he nevertheless discovered a deep interest in science and read voraciously on topics of of physics and astronomy.

Speaker 1 At the same time, he started developing a unique interpretation of the scientific discoveries that he was keeping up on, an interpretation informed by a belief in the supernatural and unorthodox religious inclinations.

Speaker 1 If we accept the analysis of thinkers like Walsh and Tresch, Poe's hoaxes weren't just frivolous stories meant to sell cheap papers.

Speaker 1 They were Trojan horses carrying an argument for something like a scientific spirituality, or perhaps a spiritually guided science.

Speaker 1 Linda Walsh explains that the true guiding arc of Poe's thinking and writing life was quote, the line at which the stress between art and science became too much.

Speaker 1

Where words failed to describe experience, experience failed to adhere to scientific principle. And words and science and experience all failed to reliably yield what was true.

⁇ End quote. Oh,

Speaker 1 that's heavy stuff.

Speaker 1 So Edgar Allan Poe was trying to both educate his readers about cutting-edge science while also critiquing a purely scientific conception of truth.

Speaker 1 Now that might seem contradictory or hard to wrap your head around. Honestly, I'm having a hard time wrapping my head around it.

Speaker 1 But hopefully, this will become a bit clearer as we make our way through some of the hoaxes.

Speaker 1 Edgar Allan Poe first dipped his toe into the world of hoaxing in 1835.

Speaker 1 At the time, he had recently been hired as a staff writer at the Richmond, Virginia-based periodical called The Southern Literary Messenger.

Speaker 1 In the June edition of the periodical, Poe had a piece published titled Hans Fall, a Tale, and later republished as The Unparalleled Adventures of One Hans Fall.

Speaker 1 The piece began sounding like a news article, claiming that the citizens of the city of Rotterdam in the Netherlands were in a state of, quote, philosophical excitement after the recent arrival of a manned balloon in the city.

Speaker 1 The balloon had originally been built by one Hans Fall, a local inventor. However, this day it was not being piloted by Fall, but by a strange-looking gnome.

Speaker 1

Poe describes the balloonist like this. He was, quote, a very droll little somebody.

He could not have been more than two feet in height.

Speaker 1 The body of the little man was more than proportionally broad, giving to his entire figure a rotundity highly grotesque. His hands were enormously large.

Speaker 1

His His hair was extremely grey and collected into a cue behind. His nose was prodigiously long, crooked, and inflammatory.

His eyes, full, brilliant, and acute.

Speaker 1 His chin and cheeks, although wrinkled with age, were broad, puffy, and double. But of ears of any kind or character, there was not a semblance to be discovered upon any portion of his head.

Speaker 1 This odd little gentleman was dressed in a loose sortie of sky-blue satin, with tight breeches breeches to match, fastened with silver buckles at the knees.

Speaker 1 His vest was of some bright yellow material. A white taffety cap was set jauntily on the side of his head.

Speaker 1 And to complete his equipment, a blood-red silk handkerchief enveloped his throat and fell down in a dainty manner upon his bosom in a fantastic bow knot of super-eminent dimensions. End quote.

Speaker 1

Man, they really knew how to do descriptions in the 1800s. I love a bow of super eminent dimensions.

Very nice.

Speaker 1 Anyway, we're told that the balloonist did not stay long in Rotterdam, but instead dropped off a letter penned by the inventor Hans Fall himself.

Speaker 1 After making his delivery, the strange balloonist then ascended until he was out of sight. The rest of Poe's article was then presented as a reprint of the Hans Fall letter.

Speaker 1 In the letter, Hans Fall explained that he had originally built his balloon to further the frontiers of science and exploration by flying to the moon.

Speaker 1 Also, he owed some money back in Rotterdam and was desperate to escape his creditors.

Speaker 1 The letter went on at great detail to describe the building of the balloon, its early tests, and the various mathematical and engineering feats involved in traveling from the Earth to the Moon.

Speaker 1 And this was really the crux of the hoax. Hans Fall's letter goes to great ends to prove that this kind of balloon journey is scientifically plausible.

Speaker 1 Or, as the letter explains, quote, lest I should be supposed more of a madman than I actually am, I will detail, as well as I am able, the considerations which led me to believe that an achievement of this nature, although without doubt difficult and incontestably full of danger, was not absolutely, to a bold spirit, beyond the confines of the possible.

Speaker 1 End quote.

Speaker 1 The idea was that by the end of the article, you would be convinced that a journey to the moon could happen, even if you weren't convinced that this particular journey had happened.

Speaker 1 To this end, the letter detailed the mathematical calculations necessary to predict the orbit of the moon and chart the shortest distance between it and the earth.

Speaker 1 Hans Fall also spent many paragraphs explaining the problems with breathing at high altitude and ultimately the vacuum of space.

Speaker 1 He gives a detailed and very technical description of a specially built air compressor that apparently allowed him to breathe comfortably at these dizzying heights.

Speaker 1 Hans Fall also claimed that he brought along a cat and described in detail how the animal reacted at various altitudes and positions between the Earth and the Moon.

Speaker 1 When Hans Fall finally reached the Moon, he described, quote, diminutive inhabitants, end quote, as far as the eye could see, and a, quote, fantastical city.

Speaker 1 Further, he explained that the gnomish messenger bearing the letter was in fact a moon man.

Speaker 1 Poe's article wraps up with the officials in Rotterdam speculating about whether or not this whole thing was a hoax.

Speaker 1 But the last word is given to an unnamed Dutch scientist who insists that anyone doubting the tale is, quote, ignorant of astronomy, and that, quote, the document is intrinsically, is astronomically true, and that it carries upon its very face the evidence of its own authenticity.

Speaker 1 End quote.

Speaker 1 Now that last line is very telling.

Speaker 1 Poe seems to be needling his audience here, suggesting that if a reader was skeptical of this tale, then that meant that he or she perhaps was too ignorant or dim-witted to understand the complex science at its heart.

Speaker 1 This is the Emperor's new clothes ploy.

Speaker 1 The scammer tells you that only an unsophisticated person would think that the emperor is naked. If you're intelligent and refined, then surely you would see the clothes.

Speaker 1 In the same way, only the smartest people believe the tale of Hans' fall.

Speaker 1 But in this case, Edgar Allan Poe's story was not a successful hoax. Some commentators wrote that they found it amusing.

Speaker 1 Another said that it will add to Poe's, quote, reputation as an imaginative writer, end quote. But no one seems to have been fooled.

Speaker 1

Now, you might be thinking, of course no one was fooled. The story is patently ridiculous.

How could anyone have fallen for something that prominently features gnomish moon men?

Speaker 1 Well,

Speaker 1 not so fast.

Speaker 1 Just two months after the Southern Literary Messenger ran Hans Fall a Tale, another moon hoax took America by storm.

Speaker 1 This hoax, authored by Richard Adams Locke, has actually come up before on this podcast. But for those that need a reminder, here's the recap.

Speaker 1 In August of 1835, the New York Sun ran a short article on page two, informing its readers that the well-known astronomer, Sir William Herschel, who was currently making observations in South Africa, had made some remarkable discoveries.

Speaker 1 Then, nothing else was reported for another four days. Then, on August 25th, the Sun ran a front-page story that they claimed was being reprinted from the Edinburgh Journal of Science.

Speaker 1 This article claimed that Herschel's new discoveries were so monumental that they would, quote, confer upon the present generation of the human race a proud distinction for all future time, end quote.

Speaker 1 But, coyly, the article did not reveal what those discoveries were. Not yet.

Speaker 1 Instead, what followed was a long reflection on the current state of astronomy, then minute details about how Herschel's telescope had been constructed and the technical specifications of his observatory in South Africa.

Speaker 1 A day later, the New York Sun finally dropped the bomb.

Speaker 1 The front page ran a huge headline heralding the amazing discoveries of Sir William Herschel.

Speaker 1 The astronomer had apparently looked through his telescope and had seen on the moon a lush, thriving ecosystem.

Speaker 1 Furthermore, he had glimpsed the most incredible creatures, moon bison, single-horned goats, mini zebras, unicorns, bipedal, tailless beavers, and most amazingly of all, humanoid creatures with giant, bat-like wings.

Speaker 1 These man-bats were also observed flying in and out of megalithic structures that Herschel guessed were their sacred temples.

Speaker 1 Now, where the tale of Hans' fall had been met with shrugs and bemused smiles, Locke's moon hoax was gobbled up by thousands of of readers.

Speaker 1 According to Linda Walsh, the blockbuster edition of the New York Sun sold 19,360 copies, making it the largest circulated newspaper ever to that point in American history.

Speaker 1 However, it should be noted that those numbers have been called into question by other historians. They may have been exaggerated by the Sun's ownership after the fact.

Speaker 1 But it is clear that the moon hoax set off a huge debate that played out over the next few weeks in the pages of many different American newspapers.

Speaker 1 While some were quick to call this out as a hoax, other commentators weren't so sure.

Speaker 1 There was clearly a solid chunk of the reading public who were fooled by the moon hoax.

Speaker 1 We know that the real astronomer, William Herschel, who legitimately was a real guy, was at first amused by the story, but later became annoyed by interviewers who seemed to think that the man-bats on the moon were real.

Speaker 1 Now, historians of this period have pointed out that it's hard to know just exactly how fooled the average reader of the sun truly was.

Speaker 1 But there's no doubt that as a hoax, it had been considerably more effective than Edgar Allan Poe's story in the Southern Literary Messenger.

Speaker 1 This apparently annoyed Edgar Allan Poe, who publicly griped that Richard Locke had ripped him off. Poe even wrote a letter to the editor of The Sun accusing Richard Locke of plagiarism.

Speaker 1 Nothing ever came of this accusation, and Edgar Allan Poe eventually had to admit that even though there may have been some similarities between his story and the hoax of Richard Locke, Locke had clearly performed the trick better than he had.

Speaker 1 So, why was it that Richard Locke's moon story worked as a hoax, while Edgar Allan Poe's story of a moon journey failed to fool anyone?

Speaker 1 Both articles attempted to convince people that fantastical moon creatures might truly exist, but one had considerably more success than the other.

Speaker 1 Now, obviously, the stumbling block wasn't the fantastical creatures themselves. In the case of the Locke hoax, some readers were willing to believe in moon beavers and man-bats.

Speaker 1 The difference seems to have been one of style. Edgar Allan Poe later reflected that Hans Fall failed as a hoax because it was written in, quote, a tone of mere banter, end quote.

Speaker 1

In other words, his hoax had been been filled with a few too many jokes and winks to the audience. He gave some of his characters silly names, like the Dutch Dr.

Rubbadub.

Speaker 1 Also, the introduction of his story read more like a work of narrative fiction than a pure science article.

Speaker 1 It's only once you get to the alleged letter of Hans Fall that the technical details that sell the reality of the story really come in.

Speaker 1 But by that point, most of the audience has already made up their minds that what they're reading is fictional.

Speaker 1 Before we even get to read about the operations of Hans Falls air compressor, he's already given us a colorful description of a ballooning moon gnome.

Speaker 1 Richard Locke's moon hoax baited the hook more effectively.

Speaker 1 The two preliminary articles were especially genius as they drummed up excitement for a big big announcement and established through long descriptions of the technical specifications of William Herschel's telescope that this was a serious piece of science news.

Speaker 1 By the time the readers of the Sun got to the descriptions of the moon bison, they were more likely to accept them.

Speaker 1 In her book, Sins Against Science, Linda Walsh outlines 11 criteria that she believes are essential in making a scientific hoax work.

Speaker 1 She argues that both attempted hoaxes satisfied most of her criteria, but Locke was more effective in using what she calls authority and versimilitude.

Speaker 1 Authority is the invoking of a known authority in the field. Where Poe attributed his discoveries to the fictional and often ridiculous Hans Fall,

Speaker 1 Locke's article claimed that that the very real, very respected astronomer William Herschel had glimpsed these wonders on the moon.

Speaker 1 For similitude is what we've already discussed. For a news hoax to work, it had to read like a real news story and follow the expected beats of a science article.

Speaker 1 It had to come across like a legitimate piece of reporting right up to the moment where the man-bat Temples are introduced. And by the way, your new heavy psych band must be called Man-Bat Temple.

Speaker 1 Now, interestingly, Edgar Allan Poe seems to have learned a number of things from his first hoaxing failure and the runaway success of Locke's moon hoax.

Speaker 1 In the future, Edgar Allan Poe was not going to make the same mistakes.

Speaker 1 So,

Speaker 1 let's take a quick break, and when we return, we'll explore exactly how Poe's hoaxing evolved after 1835.

Speaker 1 Today

Speaker 1 When experts are compiling all of Edgar Allan Poe's attempted hoaxes, there's some debate about which stories should and should not be included on the list.

Speaker 1 This is because while Poe authored at least three unambiguous attempts at news hoaxes, there are at least three other stories that play in a gray area between obvious fiction and something that might be mistaken for fact.

Speaker 1 Most of these ambiguous stories seem to have been taken as fiction by most of their readers. However, one of them, called The Journal of Julius Rodman, seemed to have fooled at least one U.S.

Speaker 1 State Department official.

Speaker 1 Published in 1840 in Burton's Gentleman's Magazine, this adventure story was presented like it was a series of excerpts from a recently rediscovered journal originally written in 1792 by an explorer named Julius Rodman.

Speaker 1 The story was essentially a fake history of American expansion that suggested that this Rodman had crossed the Rockies decades before any other European.

Speaker 1 Edgar Allan Poe had actually adapted elements from the accounts of Lewis and Clark to make this tale sound more accurate.

Speaker 1 In the 1840s, the American government was in the midst of some aggressive territorial expansion.

Speaker 1 In this environment, anything that the government could use to press a claim in contested territory became of interest,

Speaker 1 even if it was a work of fiction.

Speaker 1 Robert Greenhow, a historian in the employee of the State Department, read the story and got excited that it might help the claims of the American government in the West.

Speaker 1 He had written in a Senate document: quote: It is proper to notice here here an account of an expedition across the American continent made between 1791 and 1794 by a party of citizens of the United States under the direction of Julius Rodman, whose journal has been recently rediscovered in Virginia and is now in the course of publication in a periodical magazine in Philadelphia.

Speaker 1 End quote.

Speaker 1 Interestingly, many Poe experts do not count the journal of Julius Rodman as one of the author's hoaxes, as its presentation was so obviously fictional.

Speaker 1 Weirdly, it was transformed into a hoax by Greenhow, an official deeply invested in using whatever historical precedent he could find, however dubious, to justify American expansion.

Speaker 1 In that case, Poe created a successful hoax without even really trying.

Speaker 1 But in 1844, Poe pulled off what many experts consider to be his most carefully constructed and ultimately successful scientific hoax.

Speaker 1 This has been remembered as the Great Balloon hoax.

Speaker 1 On April 13th, 1844, a special extra was printed for the regular Saturday edition of the New York Sun. Yes, the same New York Sun that had pulled off Locke's moon hoax some nine years previously.

Speaker 1 The gloriously long 19th century headline read, quote, Astounding news by express via Norfolk, the Atlantic crossed in three days, a single triumph of mister Monk Mason's flying machine.

Speaker 1 Arrival at Sullivan's Island near Charlestown, South Carolina of mister Mason, mister Robert Holland, mister Henson, mister Harrison Ainsworth, and four others in the steering balloon, Victoria, after a passage of 75 hours from land to land.

Speaker 1 The article went on to relate exactly how this astounding feat of aeronautics had been achieved.

Speaker 1 It went into painstaking detail about the construction of Monk Mason's balloon, and in particular, the novel propeller that the inventor had built for this long-distance airship.

Speaker 1 I'll give you a little flavor of the article's technical language.

Speaker 1 It explains, quote, the screw consists of an axis of a hollow brass tube, 18 inches in length, through which, upon a semi-spiral inclined at 15 degrees, pass a series of steel wire radii, two feet long, and thus projecting a foot on either side.

Speaker 1 End quote.

Speaker 1 The article goes on like this.

Speaker 1 It also included a detailed woodcut of the airship Victoria to help readers visualize the complex machine.

Speaker 1 Now, this time Edgar Allan Poe had taken a page from his old rival Richard Locke's book and had attributed this great achievement to a real person,

Speaker 1 Thomas Monk Mason.

Speaker 1 Monk Mason was an Irish flute player, theologian, and balloonist.

Speaker 1 How's that for a resume?

Speaker 1 He had made a name for himself in the world of aeronautics back in 1837 after he had successfully flown a balloon from Dover, England across the channel all the way to Wahlberg, Germany.

Speaker 1 If Poe was going to convince readers that the Atlantic had been crossed in a balloon, then he needed to invoke the authority of Monk Mason.

Speaker 1 And because Monk Mason was a real person, Poe could draw on his real published journals to help flesh out his article with the balloonist's authentic voice.

Speaker 1 Now, I couldn't help but notice that one of the other occupants of the balloon imagined by Poe was the British author Harrison Ainsworth.

Speaker 1 Now, if you are a real our fake history head, then that name might ring a bell from our last series.

Speaker 1 Ainsworth was the historical fiction writer who was instrumental in reviving Guy Fawkes as a sympathetic figure in the 1800s.

Speaker 1

Honestly, I did not plan this. It's always weird when historical figures start haunting the podcast.

This year, it's Harrison Ainsworth.

Speaker 1 Anyway, it seems like Poe included him amongst the balloon writers as his famous name helped bolster the authority of the article.

Speaker 1 He includes a number of fake quotes from Ainsworth to help sell the veracity of the whole thing.

Speaker 1 But most significantly, this time out, Poe perfectly employed the journalistic style that would normally be used for a real scientific article. This was not written in the tone of mere banter.

Speaker 1 The article was certainly sensational, but it flowed like a news story and not like an adventure story.

Speaker 1 It also helped that the readers were being asked to accept the reality of an achievement that in 1844 seemed entirely plausible.

Speaker 1 Crossing the Atlantic in a balloon is a lot different than going to the moon in a balloon.

Speaker 1 As we've explored before on this podcast, the 19th century was marked by steady news of new ballooning achievements. As I'm always saying, you gotta open your heart to balloons.

Speaker 1 Now, interestingly enough, ballooning across the Atlantic Ocean would prove to be a uniquely challenging aeronautical feat.

Speaker 1 The first manned balloon to successfully make the journey did it in 1978, a fact that I was genuinely surprised by when I learned it.

Speaker 1 It seems like the kind of thing they would have done in the 1800s, but no, no, it took till 1978 before someone crossed the Atlantic in a balloon.

Speaker 1 And this is what made the balloon hoax so good.

Speaker 1 It was the kind of feat that seemed totally reasonable to a layperson and more incredible the more you knew about the topic.

Speaker 1 The more you knew, the more likely you were to dive into the details of Poe's article, where you would encounter some scientifically sound descriptions of balloon construction.

Speaker 1 This time, Poe didn't blow the illusion by putting a moon gnome right in your face before you were fully ready to accept a moon gnome.

Speaker 1 Linda Walsh also points out that Poe used the familiar problem solution paradigm that readers of popular science articles would have been familiar with.

Speaker 1 Right after the breathless headline, the article exclaims, The great problem is at length solved, end quote.

Speaker 1 This style remains consistent throughout the article. The whole thing concludes with a sign-off that was very typical of science reporting from the era.

Speaker 1 This is where the author marvels at what future breakthroughs could be right around the corner. Poe sums up by writing, quote, What magnificent events may ensue?

Speaker 1 It would be useless now to think of determining, end quote.

Speaker 1 And sure enough, the great balloon hoax seems to have caused a legitimate sensation.

Speaker 1 The New York Sun sold a record number of copies of the newspaper extra that day. The Philadelphia Saturday Courier estimated that the New York Sun may have moved as many as 50,000 copies.

Speaker 1 The most detailed description we have of the stir caused by the balloon hoax comes to us from Edgar Allan Poe himself.

Speaker 1 But this description needs to be handled with care because, as we've hopefully established, Poe is not always the most reliable narrator.

Speaker 1 But he would later remember this about the day that the Monk Mason balloon story hit the stands. Quote,

Speaker 1 On the Saturday morning of its announcement, the whole square surrounding the Sun building was literally besieged, blocked up.

Speaker 1 I've never witnessed more intense excitement to get possession of a newspaper.

Speaker 1 As soon as the first few copies made their way into the streets, they were bought up at almost any price from the newsboys, who made a profitable speculation beyond doubt.

Speaker 1

I saw a half dollar given in one instance for a single paper, and a shilling was a frequent price. I tried in vain during the whole day to get possession of a copy.

End quote.

Speaker 1 Yes, according to Poe, there was a full-on riot on the steps of the Sun's New York City office.

Speaker 1 Now, given that the typical price of a paper at the time was a penny, someone paying a half dollar for a paper was no small thing.

Speaker 1 Now, was Poe exaggerating?

Speaker 1 Maybe,

Speaker 1 but there is no doubt that the balloon hoax moved some newspapers.

Speaker 1 But how many people actually believed it?

Speaker 1 As always, this is a harder question to answer.

Speaker 1 Most experts agree that Poe certainly fooled more people, or perhaps made more people guess, with this particular hoax than he had with any of his other hoax attempts.

Speaker 1 Poe would remember that, quote, Of course, there was a great discrepancy of opinion as regards to the authenticity of the story, but I observed that the more intelligent believed, while the rabble, for the most part, rejected the whole with disdain.

Speaker 1 End quote.

Speaker 1 Now, this claim that the more educated people were more likely to be fooled is hard to verify.

Speaker 1 It's certainly what Poe hoped would happen.

Speaker 1 It echoes the sentiment in the Hans Fall story, where the Dutch official declares that only those ignorant of astronomy would question the truth of the story.

Speaker 1 Here, Poe insists to an interviewer that only those who didn't know much about science pish poshed the balloon hoax out of hand.

Speaker 1 Now, you could argue that if Poe made a mistake, it was that he revealed the hoax too soon.

Speaker 1 Part of the reason it's hard for historians to ascertain just how many people were fooled by the balloon hoax is that Poe almost immediately threw back the curtain on the whole thing.

Speaker 1 He came forward within a day and took credit for the whole scam.

Speaker 1 One of Poe's contemporaries, Thomas Lowe Nichols, even claimed that on the day of the extra's publication, Poe got drunk on wine and wandered down to the Sun offices where he drunkenly yelled that the story was a fake at anyone who tried to buy a paper.

Speaker 1 Now, if you know anything about the biography of Edgar Allan Poe, then this is not entirely out of character for the chaotic author. Drunkenly yelling at people was

Speaker 1 kinda Edgar Allan Poe's thing.

Speaker 1 Now, I like that detail because if it's true, then it means that the riotous scene in front of the Sun office that I quoted earlier was witnessed by Poe while he was buzzing on wine.

Speaker 1 So that's perhaps another reason to take it with a grain of salt.

Speaker 1 But beyond his drunken shenanigans in front of the Sun office, Poe did more soberly take credit for the hoax not long after.

Speaker 1 Now this might seem a little strange. You would think that part of the fun of a public deception would be seeing just how long you could keep it running.

Speaker 1 But as Linda Walsh explains, quote, scrupulously protecting his identity as a hoaxer was not for Poe.

Speaker 1 Poe wished to be publicly recognized as a writer whose scientific expertise enabled him to beat scientists at their own game and construct, quote, discoveries for the public that they could not tell from the real thing,

Speaker 1 end quote.

Speaker 1 You see, Poe's approach to hoaxing was more high-minded than many of his contemporaries. He wasn't out just to prank people.

Speaker 1 He was trying to make a sincere point about how the public engages with science. In fact, he was trying to persuade the reading public that science could only take human understanding so far.

Speaker 1 This brings us back to Poe's unique philosophy that sought to combine art, science, and spirituality.

Speaker 1 Again, I'll turn to Linda Walsh, who's obviously been a key resource for this episode, but she explains, quote, by publicly revealing his hoax, Poe demonstrated that the objective rules his readers had used to determine the truth of his science report for themselves had let them down.

Speaker 1 His public humiliation of them formed an implicit argument that they could not trust themselves to understand science, and they could not even trust scientists, since Poe had clearly bested them at their own game.

Speaker 1 Poe and his imaginative artistic colleagues alone were qualified as experts in social truth. If readers wanted truth, they would need to go through professional artists like him.

Speaker 1 By this chain of implications, Poe's hoax struck against Baconian empiricism and objectivity in favor of a culture of expertise with himself at the center of it. End quote.

Speaker 1 Whoa.

Speaker 1 So, Poe's big point was that science should not have a monopoly on truth. Art could be just as instructive as science, and science could be just as deceptive as art.

Speaker 1 So all these hoaxes, which were anchored by Poe's deep understanding of science and extensive reading of scientific texts, were actually meant as deep critiques of a purely scientific understanding of the universe.

Speaker 1 What a twist

Speaker 1 Poe thought he was lampooning science by demonstrating that its language could be co-opted to convince people of nonsense.

Speaker 1 He believed that this demonstrated that science, while helpful, was insufficient when it came to explaining deeper intuitive truths. These truths were better communicated by artists such as himself.

Speaker 1 Now, there's a lot that I love about this perspective, as I too believe that artists can communicate truths about nature and the human experience that transcend scientific data.

Speaker 1 But I also think that Poe went too far in his attempted critique of empirical science.

Speaker 1 I think his hoaxes stand as excellent satires not of science, but of pseudoscience.

Speaker 1 Poe's hoaxes all use technical scientific language to misdirect the reader.

Speaker 1 His long descriptions of the workings of an airship propeller or the elliptical orbit of the moon were scientifically sound, which distracted from the BS at the heart of his story.

Speaker 1 This is what pseudo-scientific writers do even today.

Speaker 1 They lead you down a garden path decorated with technical details and complex explanations of uncontested scientific facts, only to present something dubious, unconfirmed, or deeply ridiculous at the end of the journey.

Speaker 1 The contemporary author most guilty of this technique is one of my favorite recurring villains on this podcast, Graham Hancock.

Speaker 1 For those that are new to the podcast or otherwise don't know, Hancock is the author of Fingerprints of the Gods and other works of junk archaeology and sloppy comparative mythology.

Speaker 1 His book and now Netflix series Ancient Apocalypse are filled with long passages where he explains archaeological findings or geological theories that are generally accepted by the larger scholarly community.

Speaker 1 His books, like Edgar Allan Poe's hoax articles, are padded out with detailed summaries of scholarship that is generally uncontroversial.

Speaker 1 For instance, in his book Magicians of the Gods, there's a long-ass chapter detailing how the geological feature in Washington state known as the scablands were created at the end of the last ice age.

Speaker 1 He spends pages outlining some fairly dense geological research.

Speaker 1 Ultimately, this is all done so he can make the point that a once-fringe scientific theory concerning cataclysmic floods in the region was later proven to be correct and was accepted by the scientific mainstream.

Speaker 1 Now, everything in those pages is more or less scientifically accurate, but none of it supports his truly audacious claim that during the last ice age, there was was once a world-spanning super civilization inhabited by people with telekinetic spiritual powers.

Speaker 1 Why would Graham Hancock spend so much time telling the reader details about the hydrodynamic properties of Washington's glacial Lake Missoula in a book about ancient superarchitects?

Speaker 1 I contend that it's the equivalent of Poe describing how Hans Fall calculated the elliptical orbit of the moon, or going into detail about how his air compressor functions.

Speaker 1 It distracts from the fact that he just told you that a chubby gnome wearing a red scarf and a jaunty cap just delivered a letter in the Netherlands.

Speaker 1 If I tell you how my telescope is constructed in excruciating technical detail, maybe then you'll believe that I saw a Batman on the moon.

Speaker 1 The whole thing just seems more science-y that way.

Speaker 1 I don't think Poe and his ilk ultimately discredited science, but demonstrated how the language of science could be weaponized by conmen.

Speaker 1 One of the best ideas at the heart of the scientific method is that experiments should be be repeatable.

Speaker 1 Something can only be accepted as a fact if it can be demonstrated and other people can verify the results of your research. Similarly, good journalism is all about fact-checking.

Speaker 1 Edgar Allan Poe didn't beat the scientists at their own game,

Speaker 1 because if anyone seriously checked his claims, they would have quickly discovered that they were false.

Speaker 1 If Poe hadn't been so eager to reveal the balloon hoax himself, the whole scam would have fallen apart anyway once someone asked Monk Mason about it.

Speaker 1

In that sense, Poe was not engaged in science writing or even a parody of science writing. He was writing like a pseudo-scientist.

He beat the pseudoscientists at their game.

Speaker 1 In the end, Poe's hoax articles functioned in the same way as the chess-playing automaton. They were introduced as exciting exhibitions of cutting-edge science.

Speaker 1 They sold an illusion with an ostentatious demonstration of mechanical complexities.

Speaker 1 One was encouraged to inspect the mass of intricately arranged gears, knobs, and pistons.

Speaker 1 They clattered along loudly, convincing the audience that they were witnessing a previously unimaginable technological feat.

Speaker 1 When the deception worked, the audience was left believing that science had accomplished a miracle.

Speaker 1 But all the tech-flavored stage dressing was just a misdirection, meant to keep our eyes away from the little man working the big puppet.

Speaker 1 Okay,

Speaker 1 that's all for this week. Join us again in two weeks' time when we will explore an all-new historical myth.

Speaker 1 Before we go this week, as always, I need to give some very special shout-outs. Big ups to Derek Courtney, to Kurt Strzok, to haha, my guy Tyler Seed, to Ansel Santosa, to Megan,

Speaker 1 to

Speaker 1 Tactical Spork,

Speaker 1 to Sierra, to

Speaker 1 Bason,

Speaker 1 to Darcy Gerzanich,

Speaker 1 to Matthew Bauer, to Sebastian Armstrong, to Tanya Platero, to David Corteau,

Speaker 1 and to Razzie Briga.

Speaker 1 All of these people have decided to pledge $5

Speaker 1

or more every month on Patreon. So you know what that means.

They are beautiful human beings. Thank you, thank you, thank you for your support.

I can't say this enough.

Speaker 1 The Patreon support keeps this show going.

Speaker 1 I love

Speaker 1 you supporters.

Speaker 1 This is also your last call to go and vote on the patrons only extra episode. Go to patreon.com slash our fake history and vote in the poll that is pinned to the top of the page.

Speaker 1

If you want to get in touch with me, please send me an email at ourfakehistory at gmail.com. Find me on Facebook at facebook.com slash ourfake history.

Find me all over the web at our fake history.

Speaker 1 I'm thinking of opening up a blue sky. What do you think, folks? Should I do it? I think it's time.

Speaker 1 So I'll let you know once I'm on that particular service. Find me on TikTok at Our Fake History and please go to our YouTube channel on youtube.com slash our fake history.

Speaker 1 Subscribe and watch our videos there.

Speaker 1 As always, the theme music for our show comes to us from Dirty Church. Check out more from Dirty Church at dirtychurch.bandcamp dot com.

Speaker 1 And all the other music you heard on the show today was written and recorded by me.

Speaker 1 My name is Sebastian Major. And remember, just because it didn't happen doesn't mean it isn't real.

Speaker 1 One, two, three, four.

Speaker 1 There's nothing better than a one-play sign.