Episode #207- What Are the Olympic Myths? (Part I)

See Privacy Policy at https://art19.com/privacy and California Privacy Notice at https://art19.com/privacy#do-not-sell-my-info.

Press play and read along

Transcript

Speaker 1

You want your master's degree. You know you can earn it, but life gets busy.

The packed schedule, the late nights, and then there's the unexpected. American Public University was built for all of it.

Speaker 1 With monthly starts and no set login times, APU's 40-plus flexible online master's programs are designed to move at the speed of life. You bring the fire, we'll fuel the journey.

Speaker 1 Get started today at apu.apus.edu.

Speaker 2 Audival's romance collection has something to satisfy every side of you. When it comes to what kind of romance you're into, you don't have to choose just one.

Speaker 2 Fancy a dalliance with a duke or maybe a steamy billionaire. You could find a book boyfriend in the city and another one tearing it up on the hockey field.

Speaker 2 And if nothing on this earth satisfies, you can always find love in another realm. Discover modern rom-coms from authors like Lily Chu and Allie Hazelwood, the latest romanticy series from Sarah J.

Speaker 2 Maas and Rebecca Yaros, plus regency favorites like Bridgerton and Outlander. And of course, all the really steamy stuff.

Speaker 2 Your first great love story is free when you sign up for a free 30-day trial at audible.com slash wondery. That's audible.com/slash wondery.

Speaker 1 In April of 2024, there was a gathering in a lightly populated but historically significant corner of Greece.

Speaker 1 At the far western end of the Peloponnese you will find the Elis region and there you will find the archaeological remains of Olympia, the ritual complex that for nearly 1200 years hosted the most prestigious athletic competition in the Greek world.

Speaker 1 These days, Olympia is mainly the haunt of archaeologists and historically minded tourists, except for a brief moment a few months before the opening of a modern Olympic Games.

Speaker 1 Then Olympia becomes the site of a unique bit of pageantry meant to invoke the spirit of the ancient Games.

Speaker 1 If you were among the select group of observers invited to Olympia this past April, then you would have witnessed a group of statuesque Greek women dressed in flowing white gowns playing the role of ancient priestesses of the Temple of Hera.

Speaker 1 As part of their official duties, these priestesses performed an elaborate dance that Olympic organizers tell us was inspired by ancient Greek movement.

Speaker 1 In the course of this choreography, the priestesses gathered around a special concave mirror positioned perfectly to concentrate the rays of the sun and ignite the Olympic flame.

Speaker 1 The priestesses then called upon the god Apollo to give life to the flame, and once again, Apollo obliged.

Speaker 1 The flame was lit in a sacred urn, decorated with an ancient-looking image of a naked, bearded athlete running with an ignited torch.

Speaker 1 The urn was then solemnly brought forward by the high priestess, played this year by Greek actress Merimina.

Speaker 1 When the high priestess reached the platform, believed to be the remains of the vestibule of the ancient temple of Hera, she made a second invocation to the gods to protect the flame and the sacred truce meant to ensure peace during the Olympic season.

Speaker 1

After her invocation, the High Priestess was met by a runner. holding this year's official Olympic torch.

His torch was ignited by the flame in the sacred urn.

Speaker 1 The high priestess then passed the runner a ceremonial olive branch, the classic symbol of peace. A second priestess then reached into a cage beside the platform and released a single white dove.

Speaker 1 You know, the other classic symbol of peace.

Speaker 1 With that, the 2024 Olympic torch relay had officially begun.

Speaker 1 Over the next 11 days, the torch was passed from runner to runner on its trip to Athens, where it was turned over to the organizers of the Paris Games and yet another elaborate ceremony.

Speaker 1 From there, the torch was brought aboard the 19th century three-masted sailing ship, the Belléme, and sailed from Athens to the southern French port of Marseille.

Speaker 1 Appropriate given that tradition holds that Marseille was originally founded by Greek settlers sometime around 600 BC.

Speaker 1 At the time of this recording, the Olympic torch should be passing through France's Côte d'Or on its way to Paris to inaugurate the 2024 Olympic Games.

Speaker 1 The start of the Olympic torch relay with its pagan-inspired pageantry and antique-feeling symbolism is just one moment where the modern Olympic Games are presented as a revival and a continuation of a deeply ancient tradition.

Speaker 1 The costumes, the ancient-looking props, the Greek invocations of pagan deities all give the impression that this ceremony must have very deep roots, dating back to the origins of the games at Olympia.

Speaker 1

But this is an illusion. The lighting of the Olympic flame and the torch relay are not ancient traditions.

They are modern inventions meant to feel ancient.

Speaker 1 There was no torch relay that began the ancient games at Olympia.

Speaker 1 Now, if you seek out the article on the lighting ceremony posted at olympics.com, you will read, quote, During the Olympic Games, the Olympic flame was ignited by the sun's rays and remained lit throughout the games in a sanctuary in Olympia known as the Praitanium.

Speaker 1 For the ancient Greeks, fire was the creative element of the world and civilization. End quote.

Speaker 1 Now, this isn't exactly inaccurate. It's just missing some important context.

Speaker 1 It is true that, like all Greek and Roman religious sanctuaries, Olympia had an eternal flame kept in a building known as the Praitanium.

Speaker 1 But this flame was not ignited specifically for the Olympic Games. This was an eternal flame that was kept burning all year round in honor of Hestia, the goddess of the hearth.

Speaker 1 That flame was then used to ignite all the sacrificial fires in the sanctuary. So, yeah, Olympics.com is technically correct when they say that this fire was kept burning throughout the Olympic Games.

Speaker 1 But I think it's important to know that that fire had been burning consistently for the three years leading up to the games and it kept on burning after the games were done.

Speaker 1 The flame had nothing to do with the opening and the closing of the Olympics.

Speaker 1 Now there were some Greek city-states that staged torch relays in connection with various civic festivals.

Speaker 1 In ancient Athens, there was a particularly famous torch relay that culminated in the lighting of a flame atop the Acropolis near the altar of Prometheus.

Speaker 1 But this race had absolutely nothing to do with the Olympics. The sacred flames at Olympia were incidental to the athletic competitions staged there every four years.

Speaker 1 At the ancient games, there wasn't really an analog to the quote-unquote Olympic flame as we understand it today.

Speaker 1 Weirdly enough, the pseudo-pagan tradition of igniting the Olympic torch in Olympia and then running it to the host city is less than 100 years old.

Speaker 1 The first time the ceremony was staged was for the 1936 Olympics in Berlin, perhaps the most notorious of the modern Olympic summer games. The 1936 Games have been remembered as the Nazi Olympics.

Speaker 1 The event was used by Adolf Hitler and his propagandists to promote Nazi ideology while also softpeddling, or straight-up hiding, many aspects of the regime that the international community found worrisome.

Speaker 1 The image the Nazis wanted to project was that their Germany was the natural inheritor of the classical ideal.

Speaker 1 The Nazi fantasy of a racially pure Aryan athlete was linked to ancient Greek notions of male beauty and the perfect athletic form.

Speaker 1 As such, the Nazis really leaned into the faux paganism and veneration of an imagined antiquity that had always been part of the modern Olympic movement.

Speaker 1 The Olympic flame ceremony was initially concocted by the German Olympic organizer Carl Diem.

Speaker 1 He was the idea man behind the actresses dressed as priestesses, the lighting of the flame with a concave mirror, and then the cross-country relay to Berlin.

Speaker 1 The fake ancient ceremony caught the imagination of Nazi Minister of Propaganda Joseph Goebbels, who made sure that the ceremony was well publicized and that the progress of the Olympic torch from Olympia to Berlin was carefully reported on by regular radio broadcasts.

Speaker 1 Two years later, images of the lighting of the Olympic torch and the start of the relay became even more deeply entrenched in the public consciousness thanks to the film Olympia by the notorious propaganda filmmaker Lenny Riefenstahl.

Speaker 1 Riefenstahl had been at Olympia in 1936 with a camera crew filming the lighting ceremony. But she decided that that carefully staged-managed event still was not aesthetically pleasing enough.

Speaker 1 So So she staged another lighting ceremony for her film. She chose to film that ceremony at the ruins of Delphi, which she deemed to be more impressive-looking.

Speaker 1 Riefenstahl also decided that the real bearer of the first Olympic torch, a Greek runner known as Konstantinos Kondilis, didn't quite fit the Nazi ideal of the perfect athlete.

Speaker 1 He, too, needed to be replaced.

Speaker 1 She first substituted him with the blonde German Jürgen Ascherfeld, before pivoting to a muscular teenager she met on the side of the road in Greece named Anatole Dobriansky.

Speaker 1 Anatole combined what Riefenstahl believed was the desired Aryan physique with convincingly Greek-looking features.

Speaker 1 So, the first time most people experienced the Olympic flame ceremony through the film Olympia, they were watching something deeply manufactured.

Speaker 1 Not only was this ceremony a fake ancient rite conceived by Nazis, they weren't even watching the real fake ceremony. They were watching Riefenstahl's idealized recreation of a fake ceremony.

Speaker 1 But the weirdest part of all is that we decided to keep this ceremony.

Speaker 1 The 1936 Olympics would be the last Summer Games until the end of the Second World War. When the Olympics reconvened in London in 1948, many were keen to put the Nazi Olympics in the past.

Speaker 1 And yet this faux ancient ceremony remained alluring.

Speaker 1 The fact that it had been designed specifically for Hitler's games was ignored and eventually forgotten.

Speaker 1 The fake history that this was some ancient Greek rite was allowed to overshadow the real history that this was a ceremony popularized by Goebbels and Lenny Riefenstahl.

Speaker 1 But in a way, this is what the Olympic movement is all about. The modern Olympics have never really been about faithfully honoring history.

Speaker 1 The Olympics freely use history, myth, and pageantry to tell a story about sports and international community.

Speaker 1 Depending on which city is hosting the games, this narrative can be massaged and specially crafted to fit the needs of the local promoters.

Speaker 1 Sometimes a city defines the games, and sometimes the games define the city.

Speaker 1 Because of all this modern myth-making, most folks don't have a good understanding of the history of the ancient Olympics in Greece.

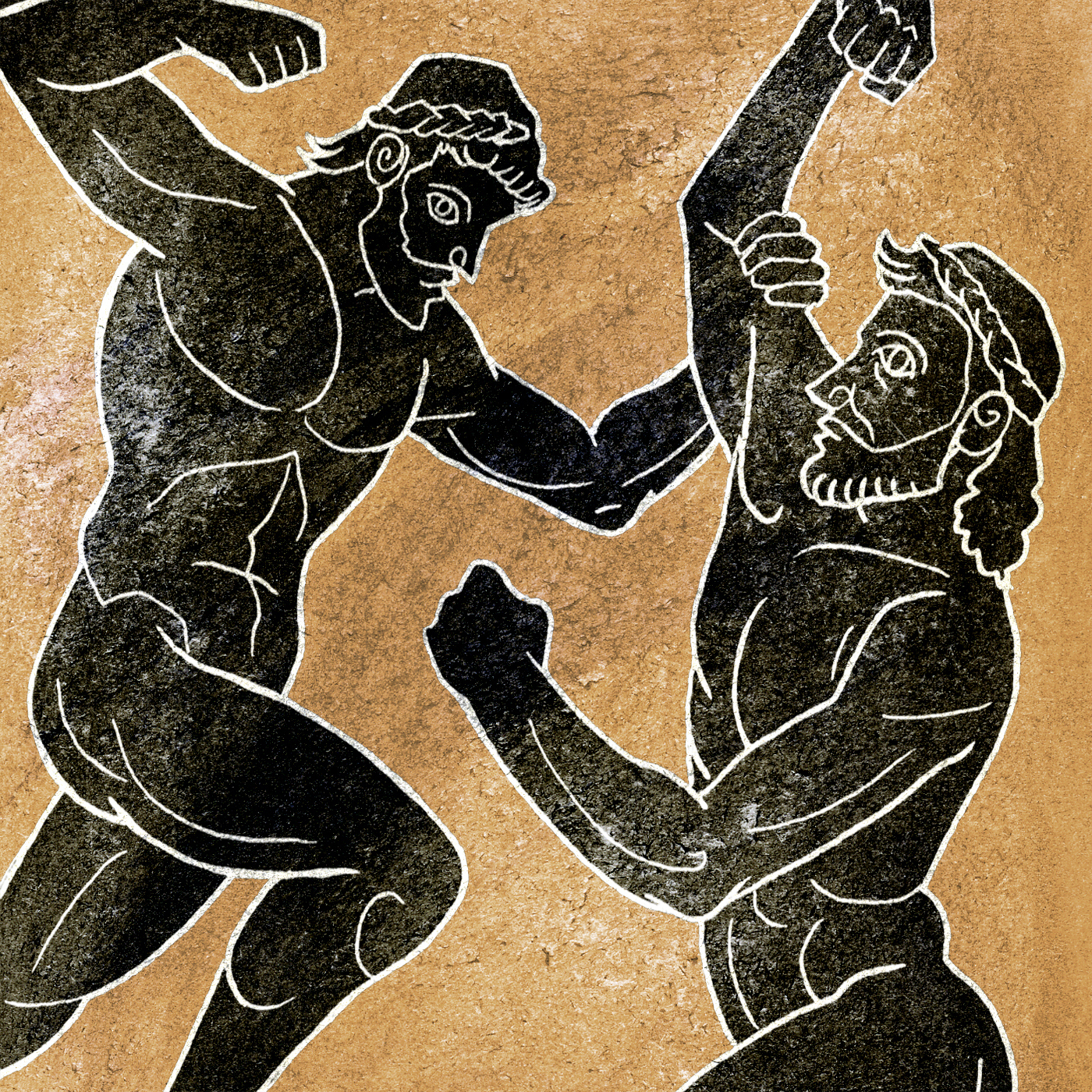

Speaker 1 The ancient games were a strange, dirty, often violent orgy of sweat and brawn.

Speaker 1 In some ways, the Greek games at Olympia, where athletes competed in the nude, competitors and spectators died on the regular, and only first place was in any way recognized, can seem quite foreign to the modern Olympic experience.

Speaker 1 But in other ways, the ancient games seem oddly familiar.

Speaker 1 So, what were the ancient Olympics actually like?

Speaker 1 Answering that question can be a little tricky given how much ancient mythology surrounds the competition at Olympia. But picking the facts out of ancient mythology is kind of what we do around here.

Speaker 1 Just how connected are our modern Olympics to Olympia's dirty games of centuries past? Let's see what we can find out today on our fake history.

Speaker 1 One, two, three, five.

Speaker 1 Episode number 207, What Are the Olympic Myths? Part 1.

Speaker 1 There's nothing better than a woman's life.

Speaker 1 Hello, and welcome to Our Fake History.

Speaker 1 My name is Sebastian Major, and this is the podcast where we explore historical myths and try to determine what's fact, what's fiction, and what is such a good story that it simply must be told.

Speaker 1 Before we get going this week, I would just like to remind everyone listening that an ad-free version of this podcast is available through Patreon.

Speaker 1 Just head to patreon.com slash ourfakehistory and start supporting at $5 or more every month to get access to an ad-free feed and a long list of extra episodes.

Speaker 1 We're talking hours and hours of exclusive Our Fake History goodness. You also get to be part of a lovely online community and vote on all the future extras that I will be creating for the patrons.

Speaker 1 So if you like this show and you want to keep it coming, then the best thing to do is go to patreon.com slash ourfake history and pick a level of support that works for you.

Speaker 1 This week, we are kicking off a trilogy of episodes on the history of the Olympic Games. Now, I'm recording this series in the run-up to the 2024 Summer Olympic Games in Paris, France.

Speaker 1 This will be the third time Paris has hosted the Olympics, making it only the second city ever after London to host the Games three times.

Speaker 1 This year's Games will also mark the 100th anniversary of Paris's last Olympics in 1924.

Speaker 1 The International Olympic Committee, or IOC, seems to have a soft spot for that kind of historical symmetry.

Speaker 1 The return to Paris also represents a return to the heart of the modern Olympic movement.

Speaker 1 The revival of the Olympic Games in the late 19th century is often credited to a French aristocrat, a man named Baron Pierre de Coubertain.

Speaker 1 In 1894, he famously hosted a meeting of international delegates at the Sorbonne in Paris, which became known as the Congress on the Revival of the Olympic Games.

Speaker 1 This gathering of officials from sporting organizations from nine different countries eventually came to the unanimous decision that an international festival of sporting competition modeled on the ancient Greek Games at Olympia should indeed be revived.

Speaker 1 This led directly to the founding of the IOC.

Speaker 1 Now, at Coubertin's meeting at the Sorbonne, Paris was put forward as the city best equipped to host the first revived Olympic Games.

Speaker 1 But eventually the Greek delegates were able to convince enough of the gathered sportsmen that Athens should host the very first modern Games. The argument was simple.

Speaker 1 Greece was the historical home of the Olympics. It was only natural that the first modern Olympics should take place in Greece.

Speaker 1 As it turned out, even in its earliest iteration, the IOC was a sucker for historical symmetry.

Speaker 1 So it was decided that Athens would host the first modern Summer Olympic Games in 1896. Eventually, Paris was confirmed as the site of the second Olympic Games in the year 1900.

Speaker 1 Now, the success of the Greek bid for the Games seems to have surprised even the Greek delegates themselves.

Speaker 1 They now found themselves in the delicate position of having to sell the idea of the Olympics to a skeptical Greek government deeply concerned about the cost of hosting such an elaborate event.

Speaker 1 But anyone who had been paying attention to the rhetoric powering the return of the Olympic Games knew that the movement was animated by a deep reverence for all things Greek.

Speaker 1 Now, obviously, the classical Greek world had loomed large in the European imagination for centuries, but the late 19th century saw a surge of renewed interest in ancient Greece.

Speaker 1 This was encouraged by the birth of modern archaeology, which in the late 19th century was providing the world with a deeper, more nuanced understanding of the ancient Greeks.

Speaker 1 Remarkable works of art and architecture that had long ago been considered lost were being rediscovered daily.

Speaker 1 Thanks to this podcast, favorite Scaliwag, father of archaeology Heinrich Schliemann, places like the ancient city of Troy that had long been assumed to be purely mythical, were shown to be at least kind of real.

Speaker 1 Schliemann.

Speaker 1 Anyway, all of this work fueled a renewed excitement about the history of ancient Greece. This came with a romantic valorization of that time and place.

Speaker 1 The Greeks of antiquity were held up as democratic idealists, artistic pioneers, philosophical geniuses, and paragons of civic virtue.

Speaker 1 The most enamored Greco-philes of the era aggressively credited the ancient Greeks with inventing, quote-unquote, Western civilization.

Speaker 1 Now, don't get me wrong, the Greek city-states of antiquity truly were fascinating. They were the birthplace of many innovations in art, philosophy, and government.

Speaker 1 However, the popular 19th-century view of Greece could often lack nuance. The ancient Greeks were often put on a pedestal and treated like one of their idealized sculptures of the human form.

Speaker 1 The Olympic revivalists most certainly saw the ancient Greeks through these rose-tinted glasses.

Speaker 1 As such, their understanding of the ancient games that they were reviving was influenced by a heavy dose of romanticism.

Speaker 1 This was best exemplified by the chief Olympic revivalist, Baron de Coubertain. He was known to write flowery odes to the perfection of ancient Greek athletics.

Speaker 1 In his mind, the ancient Olympics held in Olympia transcended the bounds of being a mere sporting competition. They represented the best of human striving.

Speaker 1 In an essay from 1908, explaining his quest to revive the ancient games, de Coubertin wrote, quote,

Speaker 1 For centuries, athleticism in its home in Olympia remained pure and magnificent.

Speaker 1 There, states and cities met in the person of their young men, who, imbued with a sense of the moral grandeur of the games, went to them in a spirit of almost religious reverence.

Speaker 1 Men of letters and of the arts, ready to celebrate the victories of their energy and muscle, assembled around them, and these incomparable spectacles were also the delight of the populace. End quote.

Speaker 1 Now, to be charitable to de Coubertain, his understanding of the ancient Olympics wasn't so much wrong as it was incomplete.

Speaker 1 It's very true that the ancient Olympics were remarkable spectacles, infused with religious significance.

Speaker 1 They certainly delighted the populace and attracted artists, writers, and intellectuals who documented and celebrated the feats they witnessed.

Speaker 1 But to suggest that these games were pure or morally unimpeachable is to ignore the facts.

Speaker 1 The ancient Olympics were a dirty, stinking mess.

Speaker 1 The humble religious sanctuary of Olympia could barely contain the roughly 40,000 ancient sports fans who descended on the site every four years.

Speaker 1 Camping conditions were famously dismal, water was scarce, and the nearly dry bed of the nearby river Elphios became a reeking outdoor latrine.

Speaker 1 Spectators were known to drop dead from heat stroke and dehydration.

Speaker 1 The fringe of the sanctuary that acted as the spectator's campground was a hive of hustlers, sex workers, gamblers, and drunks.

Speaker 1 The flies were so bad that at the start of every Olympic Games, a special sacrifice was made to the god Zeus, where he was called upon as, quote, Zeus, averter of flies, end quote.

Speaker 1 Although harshly punished if discovered, cheating and corruption were quite common at the ancient games.

Speaker 1 Given the violent nature of of some of the events and the general lack of safety for many of the others, it was extremely common for athletes to die while competing at the games.

Speaker 1 And yet, for the winners, there was glory.

Speaker 1 It was one of the only venues in the ancient Greek world where a poor fisherman could wrestle the son of a king, and potentially could triumph over him in front of an excited crowd.

Speaker 1 The ancient Olympics were far from being a pure expression of untainted athleticism, but I do think they were pretty badass.

Speaker 1 So allow me to take you on a little tour through the ancient Olympics.

Speaker 1 But I'll warn you, ancient Olympian tour guides were notorious for being liars and propagators of historical myths.

Speaker 1 The Roman-era sightseer Varro once exclaimed, quote, Zeus protect me from your guides at Olympia, end quote.

Speaker 1 Another visitor to Greece, writing a century later, named Lucian, observed the same issue and quipped, quote, abolish lies from Greece, and all the tour guides would die of starvation, since no visitor wants to hear the truth, even for free.

Speaker 1 End quote.

Speaker 1 If Lucian and Varro can be trusted, then even in ancient times, the history of the Olympics was riddled with mythology and fake history.

Speaker 1 So I think the only way to get a sense of the ancient Olympics is to dive right into that mythology.

Speaker 1 So what were the ancient Olympic Games? When did they come into being? Why were they held in an obscure corner of the Peloponnese? And what actually went down once the games had begun?

Speaker 1 Well,

Speaker 1 let's see what we can find out.

Speaker 1 For the ancient Greeks, the origin of the games at Olympia was shrouded in myth.

Speaker 1 We know from the work done by archaeologists that Olympia was being used as a ritual site as early as the 10th century BC.

Speaker 1 Some are even willing to push that date as far back as the 15th century, but that's a matter of debate among experts.

Speaker 1 There's some evidence that in the earliest times, the site was used for the worship of the earth goddess Gaia.

Speaker 1 But eventually, the site became firmly associated with Zeus, chief Olympian and king of the Greek gods.

Speaker 1 The cult of Zeus would eventually overshadow all the others at the site, but it's worth noting that the worship of female deities like Hera and Zeus' mother Rhea were also important to the religious life of Olympia.

Speaker 1 Now, before I get too far along, I should probably get out in front of a common misconception. Olympia is not in the same part of Greece as Mount Olympus, the mythical home of the gods.

Speaker 1 These two places often get confused. Mount Olympus is in the northeast of modern Greece, whereas Olympia is in the southwest, just 15 kilometers from the west coast of the Peloponnesian Peninsula.

Speaker 1 But despite the geographic distance between these two sites, the name Olympia probably came about as an intentional echo of Mount Olympus, as this too was considered one of the homes of Zeus.

Speaker 1 Accordingly, lots of Zeus-related mythology was associated with the site.

Speaker 1 Not far from the sanctuary of Olympia stands Mount Kronos, where it was said that Zeus wrestled and defeated his Titan father, winning control of the cosmos.

Speaker 1 Now, interestingly, the oldest known temple at Olympia, built around 600 BC, was traditionally associated with Zeus' wife, Hera.

Speaker 1 Some experts think that originally this temple may have been dedicated to both Zeus and Hera.

Speaker 1 Others think that Olympia may have been primarily devoted to the worship of female deities for quite some time before Zeus kind of took it over.

Speaker 1 What's clear is that in the 470s BC, a new grand temple to Zeus was built at Olympia.

Speaker 1 This temple would eventually become famous as the home of one of the most important statues in the ancient Mediterranean.

Speaker 1 Around 435 BC, the Greek sculptor Phidias completed his 40-foot statue of the king of gods.

Speaker 1 Ancient authors tell us that the throned image of Zeus was covered in a layer of ivory and was embellished with gold.

Speaker 1 In his left hand, he held a scepter topped with an eagle, and in his right he held a gold statue of the goddess of victory, Nike.

Speaker 1 That statue of Nike was said to be roughly the size of an average person.

Speaker 1 By all accounts, the statue impressed even the most cynical visitors to the temple at Olympia.

Speaker 1 Our old buddy Herodotus, father of history, father of lies, declared the statue to be one of the seven wonders of the ancient world.

Speaker 1 The Roman-era writer Pausanias, who's going to be one of our key sources in this episode, felt as though the statue felt bigger than a mere 40 feet.

Speaker 1 Even the battle-hardened Roman general Aemilius Paulus felt as though, quote, he had beheld Zeus in person, end quote, after seeing the famed sculpture.

Speaker 1 So this is where things get a little murky. Did Olympia become the site of athletic competitions because it was already deeply associated with Zeus?

Speaker 1 Or did the site become associated with Zeus because it was being used for athletic competitions? This is not exactly clear.

Speaker 1 There is a tradition that states that the first Olympic Games were staged at Olympia in 776 BC.

Speaker 1 But it may be that track events were taking place at the sanctuary well before that point.

Speaker 1 It doesn't help that the mythology concerning the origins of the games is deeply contradictory.

Speaker 1 One of the best-known stories about the foundation of the ancient Olympics is connected to the mythic cycle known as the Twelve Labors of Heracles.

Speaker 1 Now for those not familiar, Heracles, or as you might know him, Hercules, was the famous demigod son of Zeus.

Speaker 1 After a series of tragic events that involved the hulking half-god murdering his entire family, Heracles was told by the oracle at Delphi that the only way to cleanse himself of the guilt and achieve immortality was to serve his mortal cousin, King Eurystheus of Mycenae, for 12 years and undertake any tasks that the king commanded.

Speaker 1 While serving Eurystheus, Heracles was given his famous 12 labors. These included slaying the Nemean lion and killing the multi-headed hydra.

Speaker 1 But what concerns us is Heracles' fifth labor, which is honestly one of the weirder ones. Instead of fighting a monster, Heracles was tasked with cleaning out some stables.

Speaker 1 But of course, these weren't just any stables. These were the stables of King Aegeus of Elis.

Speaker 1 He happened to own over 3,000 head of oxen, blessed with health by the gods. This gave them a divinely long life.

Speaker 1 In the course of this long life, these oxen had produced a truly ungodly amount of dung that many believed would be impossible to clean up.

Speaker 1 When Heracles arrived at Elis, he promised the king that he would not only clean the stables, he would get the job done in just one day.

Speaker 1 Bemused, King Aegeus said if Heracles could clean the stables in just one day, then he would give the hero a tenth of the herd.

Speaker 1 So Heracles got to work. Using his superhuman strength, he dug into the earth and rerouted the nearby river Elphios.

Speaker 1 The river came rushing through the stables, and before long, a lifetime's worth of holy oxen dung was washed away.

Speaker 1 But King Aegeus was not impressed. Believing that he had been tricked by Heracles, the king refused to pay.

Speaker 1 So, Heracles reacted the way any ancient mythic hero would. He single-handedly instituted a regime change.

Speaker 1 He quickly raised an army, killed the king, pillaged the city of Elis, and installed a new king.

Speaker 1 Then, the ancient poet Pindar tells us that Heracles went to the plain adjacent to the river Alphaeos and there marked out a sacred precinct for his father Zeus, known as the Altis.

Speaker 1 Heracles then declared that every four years there would be a festival at that site, now dubbed Olympia, that would host athletic competitions.

Speaker 1 He then proposed that the first competitions start right away.

Speaker 1 So, just like that, the men of Heracles' hastily assembled army dropped everything and started organizing foot races and wrestling matches. So it was that the first ever Olympic Games were held.

Speaker 1 So, if if we accept this legend, then the Olympics predate what we think of as real Greek history and extend back into the so-called Age of Heroes.

Speaker 1 But even in the poet Pindar's account of Heracles' first Olympics, he suggests that the site was already significant as it was tied to the story of another Greek hero, Pelops.

Speaker 1 Pelops is the hero who gives his name to the Greek region known as the Peloponnese.

Speaker 1 The story goes that long before Heracles came to Olympia, the wandering hero Pelops became enamored with the daughter of the king of Pisa, King Oinemos.

Speaker 1

Now, obviously, this is the Pisa in Greece, not the Pisa of the Leaning Tower of Pisa in northern Italy. But of course you knew that.

You didn't need me to tell you that.

Speaker 1 But Pisa is important to the history of the ancient Olympics because we know that the city city vied with the city of Elis for control of the Olympic site. Anyway, back to the story.

Speaker 1 The king of Pisa had been told by an oracle that he would be killed by his son-in-law. So King Onamas became deeply paranoid about any suitors coming to court his daughter.

Speaker 1 In his paranoia, he instituted a test for any man who wished to marry his daughter. They would meet at Olympia, and the suitor would be given a chance to drive off with the princess in a chariot.

Speaker 1 The only catch was that the king would also be in a chariot, riding in hot pursuit. If the king caught the suitor, he would kill him, decapitate the young man, and post his head outside of the palace.

Speaker 1 When the wandering hero Pelops came along, there were already a dozen heads decorating the king of Pisa's palace walls.

Speaker 1 But after seeing the king's daughter, Pelops fell in love at first sight. So he agreed to a death race just for a chance to marry her.

Speaker 1 But Pelops knew that if he wanted to win, he needed an edge.

Speaker 1 The story goes that Pelops approached the king's royal charioteer Myrtilis, who, as it turned out, also harbored a secret crush on the king's daughter.

Speaker 1 It was agreed that if Myrtalus helped Pelops, Pelops would allow the charioteer to spend a night with the princess once he had secured her hand in marriage. Pretty skeevy, I know.

Speaker 1 So, Myrtalus secretly loosened all the pins holding the king's chariot wheels in place. The next day, the race was on.

Speaker 1 Pelops took off racing with the princess and the king followed close behind.

Speaker 1 The king had just managed to get himself up to full speed when the wheels flew off his chariot, sending King Oinemus flying to his death.

Speaker 1 The couple married, but when Myrtilus approached the queen for what he believed was his just reward, the duplicitous Pelops reneged on the agreement and threw Myrtilus off a cliff.

Speaker 1 In this story, everyone's a creep.

Speaker 1 The part of the Mediterranean where Myrtilus died was forever after known as the Myrtoan Sea.

Speaker 1 When Pelops eventually died, he was buried at Olympia in memory of his famous chariot race.

Speaker 1 The ancient Greeks believed that the Olympic chariot race was done in honor of Pelops.

Speaker 1 Now,

Speaker 1 These stories are not necessarily the most helpful when trying to piece together the real history of Olympia. But the disparate traditions do hint at a real conflict over the Olympic site.

Speaker 1 Before the building of the Temple of Zeus in the 470s, there seems to have been a violent contest between the cities of Elis and Pisa for control of Olympia.

Speaker 1 We know this because the Roman-era author Pausanias tells us that the Temple of Zeus was paid for using spoils plundered from the city of Pisa by the victorious city of Elis.

Speaker 1 Control over this important sanctuary not only had religious significance, but it also meant that your city controlled the Olympic Games, which came with enormous prestige and commercial possibilities.

Speaker 1 Now, all of this complicates our understanding of the most reasonable sounding origin story for the games. The date that is commonly given for the first historical Olympics is 776 BC.

Speaker 1 The story goes that leading up to that year, Greece was going through a period of strife.

Speaker 1 The Greek states, which were still recovering from a wave of foreign invasions, were now being rocked by pestilence and disease.

Speaker 1 This was to say nothing of the ongoing wars and disputes between the always testy city-states.

Speaker 1 In the midst of this turmoil, King Ephistos of the city of Elis visited the oracle at Delphi to get some guidance.

Speaker 1 The oracle told King Ephistos that he needed to revive the Olympic Games and, quote, declare a sacred truce for the duration of these games, end quote.

Speaker 1 The oracle insisted that this was the only way to end the plague that was afflicting Greece.

Speaker 1 So the king of Elis struck a deal with the great lawgiver of Sparta, Lycurgus, and the king of nearby Pisa Cleomenes.

Speaker 1 It was agreed that the games would be held under the auspices of the Elians at Olympia, and during the games a sacred truce would be honored.

Speaker 1 Now, on the face of it, this story seems like the most believable of the ones we've heard so far.

Speaker 1 But one of our key ancient sources, the Roman writer Pausanias, believed that this was actually a canny piece of fake history.

Speaker 1 When Pausanius visited Olympia in the second century AD, he had a chance to inspect an inscribed discus that was hung with pride in Olympia's temple of Hera.

Speaker 1 He was told that this discus was in fact the original sacred contract between the kings of Ellis, Pisa, and Sparta. But Pausanias sensed a fraud.

Speaker 1 The lettering on this discus was, to Pausanias's eyes, obviously not from 776 BC.

Speaker 1 This was clearly a much later forgery.

Speaker 1 He believed that the discus was being used as a prop to sell some historical propaganda that gave Ellis a more ancient claim to the site than their rivals Pisa.

Speaker 1 So when were the first first Olympic Games? The answer is: we really don't know.

Speaker 1 Likely, some sort of competition was being held at Olympia before 776.

Speaker 1 Even Ellis's propaganda story claims that King Ephistos was merely reviving the Olympics.

Speaker 1 But what is clear is that the ancient Olympics took a consistent shape around the 470s BC.

Speaker 1 That was when Ellis regained control of the Olympic site and built the famous Temple of Zeus.

Speaker 1 With the exception of a few notable years, the city of Ellis would control the judging and administration of the Olympic Games from that time until the games were formally banned by the Roman Emperor Theodosius in 393 AD.

Speaker 1 The fact that the otherwise obscure city of Ellis controlled the most important athletic festival in the Mediterranean is a fascinating little quirk of history.

Speaker 1 For the baseball fans in the crowd, it's kind of like how the Baseball Hall of Fame is in Cooperstown, New York.

Speaker 1 If you find yourself in Cooperstown, you're there because you live there or because you have sought out the Baseball Hall of Fame. The same thing seems to have been true of Ellis.

Speaker 1 You either lived there or you were in town for the Olympics.

Speaker 1 What's clear is that after the 470s, the Olympics were held every four years like clockwork.

Speaker 1 In the months leading up to the Games, heralds proclaiming the start of the Olympic season were sent out across Greece. They also spread word that the Echeria, or the Olympic truce, was now in effect.

Speaker 1 Now, the Olympic truce is one aspect of the ancient Olympics that has been latched onto by the modern Olympic movement.

Speaker 1 In fact, in 1992, ahead of the Barcelona Summer Games, the IOC formally revived the tradition and asked for nations around the world to cease all hostilities while the Games were on.

Speaker 1 Ahead of the next Winter Games, the 1994 Games in Lillehammer, Norway, the President of the UN General Assembly started a tradition tradition of issuing a solemn appeal to the nations of the world to honor the Olympic truce.

Speaker 1 In that solemn appeal, the President of the Assembly explained, quote, the Olympic truce, or Echakeria, is based on an ancient Greek tradition dating back to the 9th century BC.

Speaker 1 All conflicts ceased during the period of the truce, which began seven days prior to the opening of the Olympic Games and ended on the seventh day following the closing of the Games, so that athletes, artists, and their relatives and pilgrims could travel safely to the Olympic Games and afterwards return to their countries.

Speaker 1 End quote.

Speaker 1 As the President of the General Assembly expressed in that statement, it was believed that all conflict in Greece was put on hold during the Olympics.

Speaker 1 This is a beautiful idea, but most experts now believe that the ancient Olympic truce wasn't as all-encompassing as the President of the General Assembly would have us believe.

Speaker 1 Experts Christine Touy and A.J. Veal have pointed out that the truce only applied to, quote, those spectators and competitors who were traveling to and from the Games.

Speaker 1 This meant those travelers had free passage through warring city-states, end quote.

Speaker 1 So while while there was a taboo against hassling travelers on the way to the Olympics, wars did not stop during the games.

Speaker 1 In fact, there were a few notable instances in the history of the ancient Games when violent conflict disrupted the Olympics.

Speaker 1 During the Peloponnesian War, Ellis eventually allied itself with the city of Athens. This meant that in 424 BC, athletes from the enemy city of Sparta were banned from the games.

Speaker 1 An attack on the Olympics by the Spartans seemed so likely that year that armed troops were present throughout the Games.

Speaker 1 In 395 BC, the Arcadians went to war with the city of Ellis and managed to gain control of Olympia. That year, they invited Ellis' rival, Pisa, to help them administer the Olympic Games.

Speaker 1 This led to Ellis attacking Olympia during the games.

Speaker 1 The attack apparently took place during a wrestling match and resulted in the athletes running to defensive positions and fighting the invading army.

Speaker 1 By the time the next Olympics had rolled around, Ellis had once again gained control of Olympia and predictably declared that the previous Olympics were not valid and the results would not be recorded in the official records.

Speaker 1 Some things never change.

Speaker 1 All of this is to say that the Olympic truce was actually a fairly limited thing in ancient times.

Speaker 1 Wars kept raging during the Olympics, enemy groups were banned from the games, and on at least one notorious occasion, the Olympics were attacked by an invading army.

Speaker 1 There's also a romantic romantic idea that the ancient Olympics were somehow free from the geopolitical maneuvering that has often defined the modern games.

Speaker 1 As the French Baron de Coubertin said, the ancient games were quote-unquote pure.

Speaker 1

But this was obviously not the case. Greek politics often played out at the Olympics.

States were banned, games were boycotted or declared invalid.

Speaker 1 The Olympics always been a weird mix of high-minded ideals and real-world power.

Speaker 1 Okay, so once the games settled into a predictable four-year ritual administered by the city of Ellis, what were they like? Who exactly got to compete in these games?

Speaker 1 Well, let's take a quick break, and when we come back, we'll get into it.

Speaker 1 Myth tells us that all the events at the ancient Olympic Games were originally proposed by Heracles at the very first Olympics deep in the heroic past.

Speaker 1 However, our most thorough ancient source, Pausanias, tells us something different.

Speaker 1 He tells his readers that the competitions held at Olympia evolved over the centuries.

Speaker 1 Using that dubious 776 BC date as his starting point, Pausanias claims that at the very first Olympics, the only event was the stade, or a foot race of one length of the stadium, roughly 200 meters long.

Speaker 1 By the end of the first century of the games, a two-stade or 400-meter race, a long-distance race, wrestling, boxing, four-horse chariot racing, and the pentathlon were all added to the Olympic program.

Speaker 1 The ancient pentathlon was five events, as the name suggests, but the rules are fairly obscure.

Speaker 1 It seems like most of the focus was on the first three events, which were discus throwing, javelin throwing, and long jump.

Speaker 1 If a competitor could sweep those first three events, then he would be declared the winner of the pentathlon.

Speaker 1 However, if no one competitor was able to win all three events, then there would be a foot race. If it still wasn't clear who the winner was, there would be a final wrestling match.

Speaker 1 The only way you got to see all five events at the pentathlon is if the competition was close.

Speaker 1 Over the course of the next two centuries, the pancration, a type of no-holds-barred wrestling, and a foot race in full military armor were also introduced to the games.

Speaker 1 By around 145 BC, the Olympics had also introduced a handful of bareback horse racing events, two horse chariot racing, and a mule cart race.

Speaker 1 There was also a whole series of events for boys under the age of 18. This meant that starting around the mid-600s BC, there was a kind of kids' Olympics running alongside the adult events.

Speaker 1 If you were an athlete who wished to compete in the games, then you were required to report to the city of Ellis exactly one month before the start of the Olympics and register in person in front of the Olympic judges.

Speaker 1 The judges were a group of ten Ellian aristocrats, who in turn had been chosen by another twelve Elian aristocrats known as the Olympic Council.

Speaker 1 Not only did the judges ensure that the rules were followed in every event, they also oversaw the running of the entire festival.

Speaker 1 They carried with them distinctive forked staffs that they used to deal out canings to anyone thought to be breaking a rule.

Speaker 1 One ancient vase painting shows a judge standing over two pancration wrestlers, staff drawn, ready to strike an offending athlete for gouging the eyes of his opponent.

Speaker 1 When an athlete first arrived in the city, he was expected to head to the judge's office and declare himself.

Speaker 1 Before an athlete could register for any events, he had to prove a number of important things to the judges. First, he needed to demonstrate that he was the legitimate son of freeborn Greek parents.

Speaker 1 Next, he needed to swear a solemn oath that he had not committed murder or sacrilege. And finally, he needed to prove that he was registered on the citizens' roster of his native city.

Speaker 1 Now, one of the much-touted ideals of the modern games is a staunch commitment to internationalism.

Speaker 1 This is the idea that the games are a place where the nations of the world set aside their differences to compete peacefully and celebrate our shared humanity.

Speaker 1 The ancient Greeks really did not have this idea, or rather, they were only willing to extend this feeling of brotherhood to people considered fellow Greeks.

Speaker 1 Who was and was not Greek was fairly tightly policed.

Speaker 1 For instance, Greek-speaking people from parts of Asia or Egypt were often rejected from the games, especially in earlier periods.

Speaker 1 For a long time, Macedonians or Macedonians, depending on your thoughts on the pronunciation debate, were excluded from the games as they were considered barbarians by the Elian judges.

Speaker 1 Alexander the Great's father, Philip II of Macedon, who conquered Greece in the 330s BC, saw it as one of his greatest achievements that he was able to get the Macedonians recognized as Greeks at the Olympic Games.

Speaker 1 After the conquest of Greece by the Romans roughly 200 years later, the judges pragmatically decided to open the competition up to anyone in the Roman Empire, so long as they could speak Greek.

Speaker 1 If you were some random Gaul who wanted to compete in the Games, you had to do some some language study first.

Speaker 1 Now, you will sometimes hear that women were entirely forbidden from participating in the ancient Olympics.

Speaker 1 This is not exactly true.

Speaker 1 There was one way that a woman could win an Olympic event. That was if she entered a horse or a chariot in one of the races.

Speaker 1 At the ancient Olympics, the owner of the chariot or the horse, and not the driver or rider was considered the winner of the event.

Speaker 1 Now, women could not ride the horses, nor could they drive the chariots, but they could be the victorious horse owner.

Speaker 1 In 396 and 392 BC, a Spartan princess named Siniska entered a four-horse chariot that proved victorious at back-to-back Olympics.

Speaker 1 She apparently erected a lavish memorial thanking Zeus at Olympia, one of the only known monuments erected by a female champion in ancient Olympic history.

Speaker 1 The inscription on the statue apparently read,

Speaker 1 My ancestors and brothers were kings of Sparta. I, Siniska, victorious with a chariot of swift-footed horses, erected this statue.

Speaker 1 I declare that I am the only woman in all of Greece to have won this crown. End quote.

Speaker 1 I like that, Siniska. Pretty cool.

Speaker 1 Interestingly, she was not the last woman to compete in this way. Pausanias tells us that after Siniska, other noble women also started entering horses in the equestrian events.

Speaker 1 In 368 BC, another Spartan noblewoman, Eurylionis, had a chariot win the two-horse chariot event.

Speaker 1 But when it came to to female participation in the games, the equestrian events were a notable exception. In no other event were women allowed to participate.

Speaker 1 This was easy enough to police given that all the athletes at Olympia competed completely in the nude.

Speaker 1 Now, of course, there are a number of stories about how this began.

Speaker 1 One tradition has it that around the time of the first Olympics, an Athenian runner competing in the Stade tripped over his loincloth and severely injured himself.

Speaker 1 This prompted the Elian judges to declare that all future races would be conducted in the nude for safety's sake.

Speaker 1 However, another tradition claims that in 720 BC, the runner Orosippos of Megera concluded that he could run faster in the nude.

Speaker 1 Then he proved it by handily winning all of the foot races at that year's Olympics. After that, all the competitors followed the lead of Orosippos and competed in the nude.

Speaker 1 Now, it's worth noting that the famous Greek historian Thucydides was skeptical of both of these stories.

Speaker 1 He thought that all the best evidence suggested that naked athletics had become a convention much closer to his own time in the 5th century BC.

Speaker 1 What's clear is that by by Thucydides' lifetime, that is the mid-400s, it was the norm to compete in the nude all over the Greek world.

Speaker 1 Anyone training at the gymnasium was also going to be in the buff.

Speaker 1 Over time, the Greeks came to understand athletic nudity as a sign of refinement and Greek civilization. To be nude was to be a sportsman.

Speaker 1 The nudity also came to represent the democracy of the playing field. It was hard to know how rich, poor, or socially elite someone was when they were naked.

Speaker 1 While the ancient games had all sorts of restrictions about exactly who could participate, there were very few when it came to class.

Speaker 1 Slaves were excluded, but beyond that, any freeborn Greek man, however humbly born, could participate. This was sometimes uncomfortable for athletically minded kings and aristocrats.

Speaker 1 If you entered yourself in the Olympics, there was always a chance that some potter from Corinth might smack you around in a boxing match.

Speaker 1 For instance, Alexander the Great famously chose not to compete in the Olympics.

Speaker 1 One tradition, which may or may not be true, claimed that Alexander once quipped that competing in the Olympics was below him because he only competed against kings.

Speaker 1 But just because an athlete had arrived in Ellis before the cutoff date and had demonstrated that he was a freeborn Greek who had not committed a murder, that didn't necessarily mean that he was going to make it to the Olympics.

Speaker 1 For the next month, the athletes had to submit themselves to the Olympic training program prescribed by the judges of Ellis.

Speaker 1 This consisted of a series of trial matches for all of the events.

Speaker 1 Now, this was a very important process. This was the only chance that athletes had to get a sense of their competition and gauge whether or not they were in over their heads.

Speaker 1

The winner was crowned with a wreath woven from olive branches. They were also given the privilege of erecting a statue to their glory at Olympia.

But that was it.

Speaker 1 There was no consolation of a silver medal, and the shame of defeat was so intense that many unsuccessful athletes were driven to suicide.

Speaker 1 It was also illegal to drop out of an event once the games had begun.

Speaker 1 Losing was shameful to the Greeks, but dropping out was considered an act of cowardice so despicable that it would earn you a curse from the gods.

Speaker 1 In the entire history of the ancient Olympics, there's only one known instance of an athlete withdrawing, or rather running away, during the games.

Speaker 1 This was a Greek Egyptian scheduled to compete in the brutal Pancration.

Speaker 1 He apparently got so spooked the night before the event that he escaped through a window in his barracks.

Speaker 1 Not only did this earn him a lifetime ban from the Olympics, but the disgusted judges also levied a heavy fine on the athlete when they finally caught up with him.

Speaker 1 The only appropriate time to drop out was during the Ellian training camp. There was no shame with taking stock of the competition at the trial matches and bowing out before the start of the games.

Speaker 1 Sometimes a particularly strong athlete could scare away all their competition at the training camp.

Speaker 1 In his book, The Naked Olympics, author Tony Perottit explains, quote, the arrival of celebrity athletes could cause a mass desertion. Some even won wreaths unopposed.

Speaker 1 A Roman-era wrestler boasted on his memorial that all his opponents withdrew the moment they saw him undress. End quote.

Speaker 1 If that's true, then this dude must have been a serious specimen.

Speaker 1 After a month of rigorous training in Ellis, the athletes were winnowed down to only the most determined Greeks. Two days before the start of the Games, they were read one final warning.

Speaker 1 It went something like this, quote,

Speaker 1 If you have exercised yourself in a manner worthy of the games, If you have been guilty of no slothful or ignoble act, may you proceed to Olympia with courage.

Speaker 1 But those of you who have not so practiced, go wherever you please. End quote.

Speaker 1 I just love how blunt the Greeks can be sometimes. If you're not up for it, this is your last chance to piss off.

Speaker 1 Everyone else was invited to join the formal procession along the sacred road to Olympia. This was a 60-kilometer hike into the highlands that was spread over two two days.

Speaker 1 As the athletes approached the sacred altis at Olympia, the first thing they would have noticed was the massive crowd of 40,000 spectators who had already set up camp.

Speaker 1 Depending on which way the wind was blowing, before they saw them, they could probably smell them.

Speaker 1 That rich mix of sweat, urine, blood, sewage, cooking fires, and the pines of Olympia meant only one thing.

Speaker 1 The games were about to begin.

Speaker 1 Okay,

Speaker 1

that's all for this week. Join us again in two weeks' time when we will continue our look at the history of the Olympics.

I hope it gets you psyched for the 2024 Games.

Speaker 1

You know, I do love the Olympics. For all their craziness, I can't help but get wrapped up in it.

So, you know, go, Canada, go. I got to say it.

Speaker 1 But, you know, I hope everyone has fun cheering on the athletes that represent their countries. That's like the nice part of it, right? Right?

Speaker 1 Okay, before we go this week, as always, I need to give some shout-outs. Big ups to

Speaker 1 Dagwood Freitenstein McFadden, to TJP0123,

Speaker 1 to Derek Campbell, to Schliemann2, the Schliemanning.

Speaker 1 Oh, I like that. That's very good.

Speaker 1 Big ups to Hugh Rundle.

Speaker 1 To Dennis Cadera.

Speaker 1 To Spencer May,

Speaker 1 to Justin Volden.

Speaker 1 To Camille Delgrippo.

Speaker 1 To Connor Runyon.

Speaker 1 To Michael Hale

Speaker 1 to Jeremy Fishback and to Braden

Speaker 1 all of these people have decided to pledge $5

Speaker 1

or more on Patreon every month. So you know what that means.

They are beautiful human beings. Thank you, thank you, thank you for your support.

Speaker 1

Thank you to everyone who supports this show at all levels. Thank you for writing five-star reviews of the show.

Thank you for going to our TeePublic store and buying the merch.

Speaker 1 All of this stuff helps keep the lights on around here.

Speaker 1 If you would like to get in touch with me, you can always hit me up through email at ourfakehistory at gmail.com. Find me on Facebook, facebook.com/slash our fake history.

Speaker 1

Find me on Instagram at Ourfake History. Find me on Twitter at OurFakeHistory.

Find me on TikTok at OurFakeHistory. Go to the YouTube channel for OurFake History and watch the videos.

Speaker 1 Boy, oh boy, there's just so many ways to engage with Our Fake History.

Speaker 1 As always, the theme music for the show comes to us from Dirty Church. Check out more from Dirty Church at dirtychurch.bandcamp.com.

Speaker 1 All the other music you heard on the show today was written and recorded by me. My name is Sebastian Major, and remember, just because it didn't happen doesn't mean it isn't real.

Speaker 1 One, two, three, four.

Speaker 1 There's nothing better than a one-placed life.