OFH Throwback- Episode #31- What Was the Charge of the Light Brigade?

See Privacy Policy at https://art19.com/privacy and California Privacy Notice at https://art19.com/privacy#do-not-sell-my-info.

Press play and read along

Transcript

Speaker 1 If you're shopping while working, eating, or even listening to this podcast, then you know and love the thrill of a deal. But are you getting the deal and cash back? Racketon shoppers do.

Speaker 1 They get the brands they love, savings, and cash back, and you can get it too. Start getting cash back at your favorite stores like Target, Sephora, and even Expedia.

Speaker 1

Stack sales on top of cash back and feel what it's like to know you're maximizing the savings. It's easy to use, and you get your cash back sent to you through PayPal or check.

The idea is simple.

Speaker 1 Stores pay Racketon for sending them shoppers, and Racketon shares the money with you as cash back. Download the free Racketon app or go to Racketon.com to start saving today.

Speaker 1 It's the most rewarding way to shop.

Speaker 2 That's R-A-K-U-T-E-N, Racketon.com.

Speaker 3 Audival's romance collection has something to satisfy every side of you. When it comes to what kind of romance you're into, you don't have to choose just one.

Speaker 3 Fancy a dallions with a duke, or maybe a steamy billionaire. You could find a book boyfriend in the city and another one tearing it up on the hockey field.

Speaker 3 And if nothing on this earth satisfies, you can always find love in another realm. Discover modern rom-coms from authors like Lily Chu and Allie Hazelwood, the latest romantic series from Sarah J.

Speaker 3 Maas and Rebecca Yaros, plus regency favorites like Bridgerton and Outlander. And of course, all the really steamy stuff.

Speaker 3 Your first great love story is free when you sign up for a free 30-day trial at audible.com/slash wondery. That's audible.com/slash wondery.

Speaker 5 Hello, and welcome to this throwback episode of Our Fake History. This week, I'm throwing you back to season two and episode number 31 of the podcast, What Was the Charge of the Light Brigade?

Speaker 5 Our last series on the Great East Asian War got me thinking about the history of human conflict in general.

Speaker 5 Now, if you listen to that series on the Great East Asian War, then you know that that conflict was filled with disastrous military blunders.

Speaker 5 Now, when you learn about a military blunder, it's very easy to look on from a distance and think, well, I could have done that better. I would not have made that disastrous decision.

Speaker 5 There's a little bit of Schadenfreude from the reader of history. You almost want to laugh at the terrible decisions made by these inept leaders.

Speaker 5 But it's important to remember that history isn't just a movie or a funny story that we're hearing. These terrible decisions actually led to real people dying.

Speaker 5 And as much as it might be fun to scoff at a bad leader, we need to remember that human lives were at stake.

Speaker 5 So, I thought I would take you back to one of the best-remembered military blunders in Western history, the infamous Charge of the Light Brigade.

Speaker 5 This was a disastrous British cavalry charge that took place at the Battle of Balaclava during the Crimean War of the 1850s.

Speaker 5 This embarrassing and tragic military blunder was then transformed into a story about the sacrifice of the common soldier by the British poet Alfred Lord Tennyson.

Speaker 5 Now, obviously, the Crimean War and the Great East Asian War of the late 16th century are incredibly different conflicts.

Speaker 5 However, both wars were punctuated by bumbling aristocrats throwing away lives and resources because of their own incompetence.

Speaker 5 In both cases, the stories would be funny if they weren't so tragic.

Speaker 5 I also wanted to take you back to the Crimean War and the 1850s because it segues nicely into our next episode.

Speaker 5 We are going to be returning to Victorian Britain to explore one of the weirder aspects of that time and place.

Speaker 5 So you can look forward to that.

Speaker 5 Alright, let's get into episode number 31.

Speaker 5 What was the charge of the light brigade? Enjoy.

Speaker 5 On December 2nd, 1854, Britain's poet laureate Alfred Lord Tennyson was flipping through his edition of The Times when he came across a brutal description of the Battle of Balaklava.

Speaker 5 The battle had been fought around a month and a half earlier on the strategic Crimean peninsula in the Black Sea.

Speaker 5 The British and their French and Turkish allies had fought their Russian adversaries to a bloody stalemate while trying to defend their landing site at Balaklava harbor.

Speaker 5 The article told the tale of a complicated and largely undecided battle, punctuated by a particularly dramatic moment.

Speaker 5 The Leip Brigade, a company of nearly 600 British cavalrymen, had been almost completely destroyed after they had engaged in what appeared to be a nearly suicidal charge directly into the mouths of Russian cannon.

Speaker 5 Tennyson was moved.

Speaker 5 In this one doomed cavalry charge, he saw everything that was to be admired in Victorian manhood, bravery in the face of impossible odds, sacrifice for the glory of empire, and unquestioning obedience to the superiors.

Speaker 5 Mere minutes after finishing the article, Tennyson would pen the following verses Quote Half a league, half a league, half a league onward, all in the valley of death, rode the six hundred.

Speaker 5

Forward the light brigade, charge for the guns, he said. Into the valley of death, rode the six hundred.

Forward the light brigade. Was there a man dismayed?

Speaker 5

Not though the soldier soldier knew someone had blundered. Theirs is not to make reply.

Theirs is not to reason why. Theirs is but to do and die.

Into the valley of death rode the six hundred.

Speaker 5 So read the first two stanzas of what would become The Charge of the Light Brigade, one of the most popular poems of the Victorian age.

Speaker 5 The completed poem was published in a pamphlet and almost immediately became a national hit.

Speaker 5 Copies of the Charge of the Light Brigade even made their way over to soldiers still fighting in the Crimea.

Speaker 5 By the end of the 19th century, it was generally expected that any good British school child should be able to recite the poem from memory.

Speaker 5 Tennyson's poem had taken this obscure cavalry charge and transformed it into a thoroughly mythological event.

Speaker 5 Tennyson's doomed six hundred of the Light Brigade seemed to echo the doomed 300 Spartans of Thermopylae. Doubling the number just seemed to double the bravery.

Speaker 5 It became a poetic shorthand for all heroic lost causes and the unquestioning sacrifice of the soldier. But how much did Tennyson's poem reflect the reality of the charge of the light brigade?

Speaker 5 Was this really a heroic display of discipline under fire? Or was this actually a sloppy and pointless military blunder that wasted the lives of hundreds of men.

Speaker 5 What really happened during the charge of the light brigade, and who should we blame for one of the 19th century's most famous military mistakes?

Speaker 5 This is our fake history.

Speaker 5 Episode number 31. What was the charge of the light brigade?

Speaker 5 Hello, and welcome to Our Fake History.

Speaker 5 My name is Sebastian Major, and this is the show where we look at historical myths and try and determine what's fact, what's fiction, and what is such a good story that it simply must be told.

Speaker 5 This week, we are exploring one of the most legendary military maneuvers of the 19th century, the doomed charge of the light brigade.

Speaker 5 Now, in the world of cavalry charges, there aren't too many others that have so firmly lodged themselves in the popular historical imagination. I mean, be honest with yourselves.

Speaker 5 How many other cavalry charges could you name?

Speaker 5 Okay, I know there's a few of you out there that follow this stuff real close, but for most of us, I think the charge of the Leip Brigade is about as far as it goes.

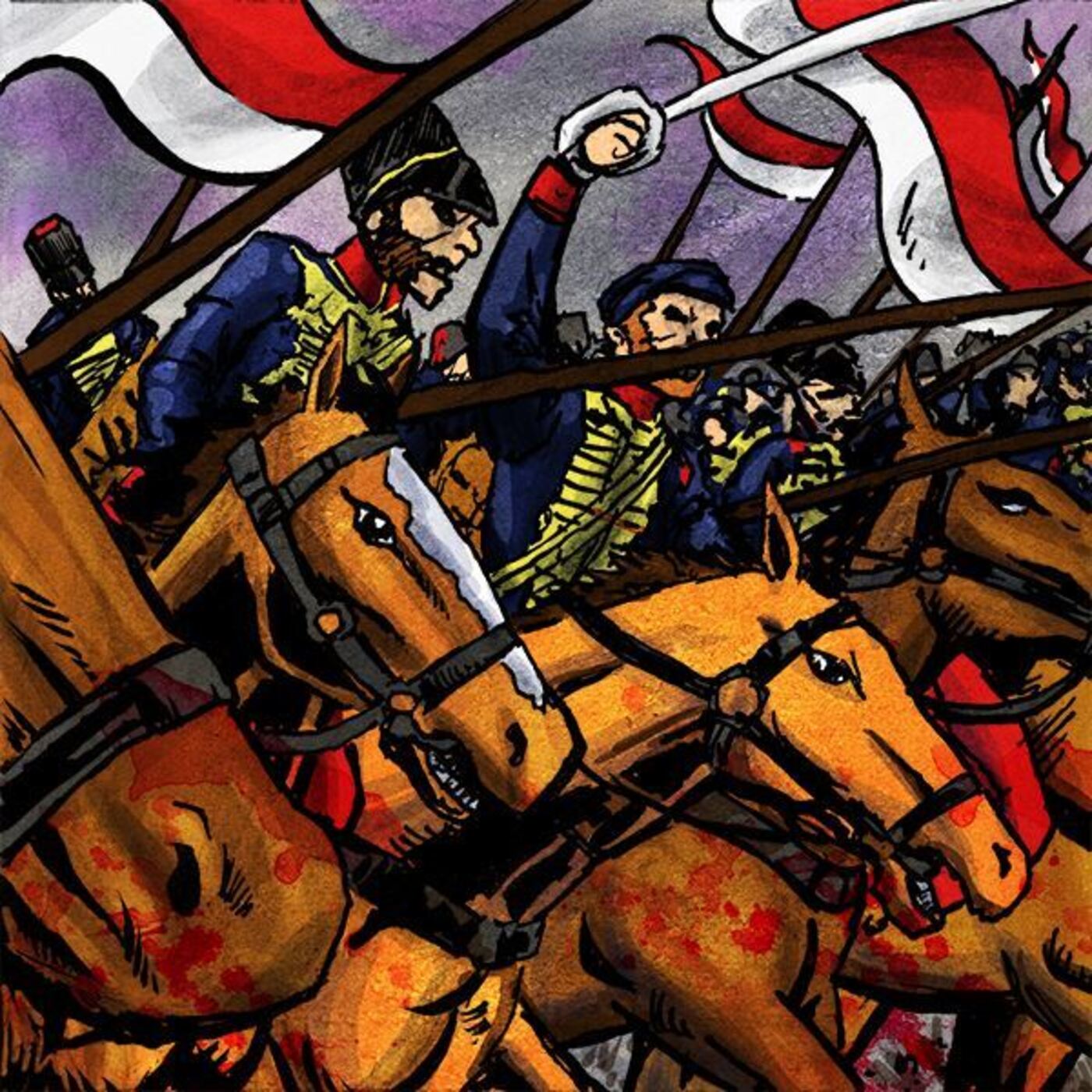

Speaker 5 I mean, for my money, the only other cavalry charge that comes close to the fame of the Leip Brigade would have to be the great charge of the Polish Hussars led by King Jan Sobieski in 1683.

Speaker 5 That was the charge that broke the Turkish siege of Vienna and basically saved that city from Turkish domination.

Speaker 5 It's often seen as the moment that turned back Ottoman expansion in Europe and changed the fate of Western history.

Speaker 5 But if Jan Sobieski's charge was the ultimate victorious cavalry action, I mean, some of his guys actually wore wings on their back. How cool is that?

Speaker 5 Then the charge of the light brigade has to be the ultimate military disaster.

Speaker 5 Now, the legend of this British charge against the Russians would have us believe that despite the fact that hundreds of men died and no strategic advantage was won, this was somehow a heroic moment.

Speaker 5 Tennyson's poem was in large part to thank for this perception. For Tennyson, the fact that the charge was costly and stupid wasn't the point.

Speaker 5 The point was that the British soldiers would do costly and stupid things if that's what the Empire required of them.

Speaker 5 After all, he wrote, quote, theirs was not to reason why, theirs was but to do and die, end quote.

Speaker 5 This cast the cavalrymen as heroic pawns who were not able to, quote, make reply to ridiculous orders.

Speaker 5 But recent examinations of primary sources, especially by historians Terry Brighton and Julian Spilsbury, have painted a very different picture of the men of the Light Brigade.

Speaker 5 Perhaps the men of the cavalry had a great deal more to do with this disastrous military maneuver than Alfred Lord Tennyson would have us believe.

Speaker 5 But before we can get into that, we first need to place this charge within the larger conflict of the Battle of Balaclava, in which it took place.

Speaker 5 And before we can understand the Battle of Balaclava, we need to get some context about the Crimean War, the 19th century clash of empires that set the stage for this legendary event.

Speaker 5 In many ways, the charge of the Light brigade is perfectly emblematic of the Crimean War in general. It was rash, bloody, largely pointless, and deeply infused with the 19th century ideals of empire.

Speaker 5 Let's check it out.

Speaker 5 So, what was the Crimean War? Well, like many wars, the causes were relatively simple, but the pretext was pretty complex.

Speaker 5 The conflict broke out in 1853, making it the largest European war to erupt since the defeat of Napoleon. It all centered around the declining empire of the Ottoman Turks.

Speaker 5 By the mid-19th century, the once mighty Ottoman Empire was not what it used to be.

Speaker 5 In the 1820s, many of the independence movements in Greece, Egypt, Syria, and many of the Balkan territories had considerably diminished Turkish territory and suggested to many that it would not be long before the entire Ottoman Empire completely disintegrated.

Speaker 5 This was certainly not lost on the Tsar of Russia, who saw this as a golden opportunity for his own imperial ambitions. The Tsar at the time was a man named Nicholas I,

Speaker 5 the great-grandfather of our podcast favorite, Nicholas II.

Speaker 5 In 1853, the Tsar would describe the Turkish Empire to a British ambassador in the following terms. Quote, We have on our hands a sick man, a very sick man.

Speaker 5 It would be a great misfortune if one of these days he should slip away from us, especially before the necessary arrangements have been made. End quote.

Speaker 5 This exchange would later be elaborated on in the British papers, and Turkey would be labeled the quote sick man of Europe.

Speaker 5 All of the major European powers were worried about their rivals potentially getting an edge on them by claiming Turkish territory for their own.

Speaker 5 Russia dreamed of having a Mediterranean port to gain better access to the markets there and exert their influence in a new geographic region.

Speaker 5 If the Russians could take Constantinople, today's Istanbul, they would have an amazing strategic base in the Mediterranean.

Speaker 5 This was completely unacceptable to the French, who were currently the dominant naval power in the Mediterranean region. A Russian presence could potentially disrupt their North African Empire.

Speaker 5 For the British, their main concern was, of course, India. Russian meddling near Egypt could potentially disrupt their incredibly lucrative trade routes with the subcontinent.

Speaker 5 Basically, none of the great powers could stomach one of their rivals gobbling up Turkey and getting an edge on them.

Speaker 5 So the cause of the war was good old-fashioned imperial ambition, or the need to check the ambitions of your imperial rivals. But the actual pretext for the war was far more convoluted.

Speaker 5 You see, the Tsar of Russia liked to promote himself as the protector of the world's Orthodox Christians.

Speaker 5 Meanwhile, the leader of France, a nephew of the late great Napoleon Bonaparte, who dubbed himself Napoleon III, had started promoting himself as the heir to the great crusader kings and the protector of all the Catholics in the Holy Land.

Speaker 5 In 1853, a riot broke out in Jerusalem between Catholic and Orthodox monks around access to the Church of the Holy Sepulchre.

Speaker 5 In the end, a number number of Orthodox Christians were left dead, and the Tsar was looking for answers. You see, this was exactly the pretext that Nicholas I needed.

Speaker 5 He claimed that the Turkish police had not done enough to protect the Orthodox pilgrims, and so now it was up to him and the Russian army to occupy Turkey and clean house.

Speaker 5 Turkey became very wary of this and went to Britain and France asking for protection should the Russians invade.

Speaker 5 In In October of 1853, the Russians massed forces along the Danube, threatening the Turkish border. The Turks responded by declaring war on Russia, and the conflict had officially begun.

Speaker 5 Now, the British and the French didn't jump in right away, as they were hoping that the Turks might be able to hold off the Tsar on their own.

Speaker 5 But after a catastrophic Turkish naval defeat on November 30th, that the British and French denounced as a massacre, their involvement involvement was all but guaranteed.

Speaker 5 By March, the press in Great Britain had become completely gripped by war fever.

Speaker 5 The Tsar was being depicted as a scheming warmonger in political cartoons, and British pride would have nothing less than a decisive victory against the Russians.

Speaker 5 The French would declare war on Russia on March 26th, 1854, and the British would follow suit a day later.

Speaker 5 So I suppose you're asking, why do we bother calling this conflict the Crimean War?

Speaker 5 Well, that's because most of the war's action was destined to take place on the Crimean Peninsula.

Speaker 5 This is the protrusion on the north coast of the Black Sea that contains the important port city of Sevastopol.

Speaker 5 Now, as many of you know, that little peninsula has been in the news again in recent years.

Speaker 5 It was, until quite recently, a part of the Ukraine until Russia was able to annex it in a move that is still highly contested by the international community.

Speaker 5 But back in 1854, the peninsula was still just the southernmost part of the Russian Empire and the key to their naval control of the Black Sea.

Speaker 5 The Allied plan was to land an invasion force on this peninsula, capture Sevastopol, and basically knock out all Russian naval capability in the region.

Speaker 5 If the Allies held that key port, then the Russians would never be able to get their boats anywhere near the Bosphorus Strait, the Sea of Marmora, and on into the Mediterranean.

Speaker 5 The strategy was logical enough, but the execution was nothing short of imbecilic. The Allied invasion was disorganized, poorly planned, and disastrously managed on the ground.

Speaker 5 You see, this had been the first major military engagement fought by the British since the death of the nearly mythical Duke of Wellington some two years previous.

Speaker 5 The Iron Duke, as he was known, had famously dealt Napoleon his final defeat at Waterloo.

Speaker 5 He had been the architect of the early Victorian army, but his death had left a gaping hole in the administration of the armed forces and created what Prince Albert had called, quote, a mere aggregate of regiments, end quote.

Speaker 5 Gone, too, was the Duke's always formidable supply chain and management skills.

Speaker 5 The result were boats turning up with dead horses, supplies being dropped at the wrong spots, hygiene deteriorating in the camps, and in some cases, British soldiers starving to death while huge supplies of food rotted on beaches mere miles away.

Speaker 5 The Crimean War was an ungodly mess of poor planning, squandered chances, and needless bloodshed.

Speaker 5 It was the prototypical stupid war, fought for obscure strategic regions and managed terribly on the ground. It reminds one of Vietnam, Iraq, the Falklands, and a million other misguided conflicts.

Speaker 5 So it's in this context that we get the doomed cavalry action that was the charge of the Light Brigade. So, what actually happened that fateful day in 1854?

Speaker 5 Well, before we can get to that, we first need to introduce our cast of characters. And believe me, these guys are colorful.

Speaker 5 Now, around the time of the Crimean War, an apocryphal story started making the rounds that a Russian soldier had commented that, quote, the British fight like lions.

Speaker 5 Luckily, Luckily, they're led by donkeys. Now, there's quite a bit of debate about whether or not that was actually said at the time.

Speaker 5 Many have pointed out that it echoes an old military saying that goes back to ancient times. Other people have pointed out that it's been attributed to a German general in World War I.

Speaker 5 But whether or not it was actually said, it's hard not to agree with the sentiment. The leadership of the British armed forces, specifically the cavalry in 1854, was best described as donkey-ish.

Speaker 5

At the Battle of Balaclava, there seemed to be a perfect storm of these donkeys all acting together. So let's introduce them.

Donkey number one, Lord Raglan.

Speaker 5 The commander-in-chief of the British forces in the Crimea was the first Baron of Raglan Fitzroy Somerset, but to us he'll just be Lord Raglan.

Speaker 5 By 1854, Raglan had a long and distinguished military career. He had served as the Duke of Wellington's military secretary throughout the Napoleonic Wars.

Speaker 5 During the battles with Napoleon, Raglan had distinguished himself for bravery and even lost his right arm to a French gun during the Battle of Waterloo.

Speaker 5 But despite this, he had always been the doting second banana to the visionary Lord Wellington.

Speaker 5 When the Duke passed away two years before the Crimean War, he left an awfully big big pair of wellies to fill.

Speaker 5 Raglan was the obvious choice as a successor, but he was not nearly the general that his mentor had been. He had a reputation for good-hearted honesty.

Speaker 5 The Duke of Wellington had even once commented that he, quote, wouldn't tell a lie to save his life, end quote.

Speaker 5 But by the time the Crimean War rolled around, whatever talents Raglan once had had completely faded. In fact, at the age of 65, he had never once led men in the field himself.

Speaker 5 Even worse, his eyesight was deteriorating, so it was often difficult for him to see what was going on on the battlefield.

Speaker 5 Raglan's incompetence would eventually become legendary, and he would be blamed for the mismanagement of the entire conflict.

Speaker 5 There's even a story that Raglan, being a veteran of the Napoleonic Wars, was constantly confusing his allies and enemies. For him, the French were the enemy.

Speaker 5 Let's sally forth and get the French, boys.

Speaker 5 But of course, in the Crimean War, the French and the British were allies, and the Russians were the enemy. Now, this story probably isn't true.

Speaker 5 It was originally told to me by a history professor of mine back in my second year of university. And since then, I have not been able to track down a reputable source that includes it.

Speaker 5 But whether or not that little detail is true, the one thing that all historians seem to agree on was that Raglan was a very poor general.

Speaker 5 He issued confusing, often vague orders and failed to capitalize on golden battlefield opportunities. Now let's move to donkey number two,

Speaker 5 Lord Lucan.

Speaker 5 George Bingham, the fifth Earl of Lucan, or just Lord Lucan to us, was fifty-four years old when he shipped out to the Crimea.

Speaker 5 He was the commander of the 17th Lancers, one of the most most distinguished cavalry regiments in the British Army until 1837, before being named the commander of the entire cavalry division at the start of the Crimean War.

Speaker 5 Now, this impressive rank might seem to suggest that he had had a long and illustrious military career, but that was completely not the case with Lord Lucan.

Speaker 5 You see, at the time, the British Army allowed landed aristocrats to purchase army commands. You would still have to rise through the ranks.

Speaker 5 You couldn't just jump directly to the rank of major or lieutenant colonel.

Speaker 5 However, particularly canny gentlemen knew exactly how to game the system, to get to the highest rank the quickest without ever having to engage in the nasty business of going to war.

Speaker 5 Lucan was not only very rich, but he was also a master of this game.

Speaker 5 Basically, you would buy a rank and then immediately go on half pay or part-time service, so you wouldn't be shipped out if your regiment, say, got shipped to India.

Speaker 5 As soon as a higher position in a better regiment opened up, you would simply buy that rank, go on half-pay, and repeat the process.

Speaker 5 By doing this, Lucan found himself in command of a very impressive regiment without having ever commanded men on the battlefield.

Speaker 5 The cavalry was particularly rife with this type of pay-to-play activity. The aristocrats seemed to be attracted to the prestige of the cavalry.

Speaker 5 They liked their role in the official parades, and let's not forget the fact that you get to ride a horsey.

Speaker 5 When he became the commander of the 17th Lancers, Lucan was able to pass over more qualified men, some of whom had actually fought against Napoleon, simply because he was the highest bidder.

Speaker 5 Now, this seems bananas, but historian Terry Brighton explains the logic of this system.

Speaker 5 He tells us, quote, if the upper class commanded the army, then the army could not become a threat to the upper class.

Speaker 5 The French Revolution had succeeded, at least partly, because it had gained the support of middle-class army officers, men who had risen to their positions on merit.

Speaker 5 English aristocrats were not about to let that situation develop in their own land. End quote.

Speaker 5 And herein lies the great Achilles' heel of the British in the Crimean War. Effectiveness was sacrificed to protect the status quo of the class system.

Speaker 5 But even amongst the many talentless rich who occupied the top spots of the cavalry, Lucan was particularly disliked.

Speaker 5 He spent a great deal of his own money bedecking his soldiers with lavish uniforms, earning his regiment the name of Bingham's Dandies.

Speaker 5 But if he ever caught one of his men with any piece of the uniform out of order, he had them publicly flogged.

Speaker 5 In fact, he quickly gained a reputation for leveling severe and violent punishments for the tiniest infractions.

Speaker 5 His cruel treatment of tenant farmers on his estates in Ireland during the potato famine quickly got him labeled the most hated man on the island.

Speaker 5 Even amongst other aristocrats who had no love for Irish peasants, he had a reputation for being especially brutal and heartless.

Speaker 5 He was also a mean and abusive husband, which helped him earn the loathing of his brother-in-law.

Speaker 5 Their ongoing feud was so nasty and disruptive that the Duke of Wellington himself had once tried to intervene to bring the two men together.

Speaker 5 After failing miserably at this task, the Duke apparently quipped that it was easier to win the Battle of Waterloo than to get these two to drop their feud.

Speaker 5 Interestingly enough, Lord Lucan's hated brother-in-law, Lord Cardigan, is the third donkey in our story. So let's take a look at him.

Speaker 5 Donkey number three is James Brundell, the 7th Earl of Cardigan, brother-in-law of Lord Lucan and commander of, you guessed it, the Light Brigade.

Speaker 5 Now before you ask, no, he did not invent the cardigan as is sometimes claimed. But yes, the cardigan sweater is named after him.

Speaker 5 Apparently, early cardigans looked like the sweaters worn by cavalry officers. Well, Lord Cardigan was the most famous or perhaps infamous cavalry commander of his day.

Speaker 5 So his name got associated with the sweater. Now, Lord Cardigan is such a larger-than-life character that it's hard to believe that he ever actually existed.

Speaker 5 He is like the cartoon version of the pompous 19th-century British aristocrat. He was vain, petty, arrogant, and seemed to take particular delight in humiliating his underlings.

Speaker 5 Much like his brother-in-law, he had risen to his position by using the same trick of purchases and half-pay until he found himself at the head of a company of Hussars.

Speaker 5

And also, Lord Cardigan had the ultimate 19th-century facial hair. Go to the Facebook page, go to the website, look at the picture I've got posted of this guy.

He is

Speaker 5

ridiculous. Now, Lord Cardigan had always had a reputation for being stupid and mean.

Apparently, as a child, he fell from his horse and sustained a nasty head injury.

Speaker 5 His family apparently thought that he was never fully right after that accident. Well, his career in the cavalry would seem to have proved them right.

Speaker 5 His reputation for pettiness was fully cemented after he dragged a subordinate officer into a court-martial for ordering stable jackets that he didn't like.

Speaker 5 And apparently, these stable jackets had been the ones that Cardigan himself had picked out.

Speaker 5 The court-martial determined that Cardigan was being ridiculous and actually ruled in favor of the less senior officer and relieved Cardigan of his command.

Speaker 5 But two years later, Cardigan was able to buy himself the command of another unit and so his reputation continued to grow.

Speaker 5 His hussars were nicknamed the cherry bums because of the particularly garish red pants that he had all of his riders wear.

Speaker 5 And of course, he continued to humiliate the more experienced officers that he had paid to outrank.

Speaker 5 Perhaps the most telling incident of Cardigan's pettiness and vanity was demonstrated by the so-called black bottle incident.

Speaker 5 On one particular night, the Inspector General of the Cavalry and his staff were dining with Cardigan and his officers.

Speaker 5 Cardigan had insisted that only champagne was to be served at his officers' table, But as the night progressed, one of the inspector's staff requested some red wine.

Speaker 5 Not wanting to be rude, one of Cardigan's officers, a certain Captain Reynolds, ordered that a bottle of red wine be brought to the table.

Speaker 5 When Cardigan saw the bottle, he apparently freaked out and started screaming, Black bottle, black bottle, who would dare bring a black bottle to my table?

Speaker 5 When Reynolds stepped up and tried to explain himself, Cardigan had him arrested.

Speaker 5 From that day onwards, Cardigan harassed Reynolds so unrelentlessly that eventually Reynolds had to resign from the cavalry.

Speaker 5 Lord Cardigan's continued abuse of his officers, including an incident where he nearly dueled with one of his disgruntled underlings, eventually earned him a vile reputation that spread well beyond the armed forces.

Speaker 5 In the years leading up to the Crimean War, there were demonstrations in the streets of London to try and get him removed from from his command.

Speaker 5 Once he was surrounded by an angry mob at a railway station who booed and heckled him.

Speaker 5 There were actually two instances when Cardigan tried to go to a theater, but he had to be asked to leave because the crowd became so agitated at the sight of him.

Speaker 5 Apparently the crowds booed, hissed, and chanted black bottle until Cardigan could be ushered to safety.

Speaker 5 All this is to say that there were few people more roundly despised in London society than Lord Cardigan and his brother-in-law, Lord Lucan.

Speaker 5 So you can imagine the shock and uproar when both men were appointed to such high-profile positions in the army at the outset of the Crimean War.

Speaker 5 Lucan as commander of the cavalry and Cardigan as commander of the light brigade.

Speaker 5 So on that fateful day in October, the day that Tennyson would immortalize in verse for generations, the men of the light brigade were commanded by the three donkeys.

Speaker 5 A half-blind general's assistant who couldn't tell his French from his Russians, the most hated man in Ireland whose favorite pastime was flogging his men, and a man so disliked in London that he couldn't even go to the theater.

Speaker 5 They all hated each other, and not a single one of them had ever commanded men in battle before.

Speaker 5 God,

Speaker 5 I wonder how this is going to turn out.

Speaker 5 The Battle of Balaklava was fought on October 25th, 1854, and was the second major battle fought in the Crimea during the conflict.

Speaker 5 The British had scored an early victory against the Russians at the Battle of Alma and had established a foothold on the Crimean Peninsula.

Speaker 5 The next step was to lay siege to the port city of Sevastopol, which had remained the main strategic objective of the Allied forces.

Speaker 5 The Battle of Balaklava was basically the Russian attempt to break the siege and relieve those weathering the storm in the city.

Speaker 5 Now, to get the full understanding of this event, I'm going to need to describe the geography of the battleground.

Speaker 5 If you're having a hard time visualizing what I'm saying, then head to the website or the Facebook page for this episode. I'll have a map posted there and hopefully that'll help.

Speaker 5 The battlefield was basically a series of hills and valleys, which makes it kind of complicated. So let's start by imagining a huge valley surrounded on all sides by hills.

Speaker 5 The hills on the southwest side of the valley were where the British set up. These were the so-called Sapune Heights.

Speaker 5

At the other end of the valley, the northeast side, there was another set of hills. These were called the Fedukian Heights, where the Russians set up.

Simple enough.

Speaker 5

Now imagine this. In the middle of the valley, there was another ridge of hills that ran between the British and the Russian positions.

These were called the Causeway Heights.

Speaker 5 At the beginning of the battle, the Turks had set themselves up in small makeshift forts in that position. So the result was a big valley divided into two smaller valleys by the Causeway Heights.

Speaker 5 Got it? If not, check the map. The Russians started the battle by having their Cossack cavalry charge the Turkish positions on the causeway heights.

Speaker 5 The Turks hadn't really prepared their forts very well, and they were very quickly overrun. As the Turks fled from the forts, the Cossacks mercilessly chased them down and sliced them to pieces.

Speaker 5 Watching all of this from their perch at the Sapune Heights was the light brigade, and apparently the men started getting antsy.

Speaker 5 They wanted to chase after the Cossacks, Cossacks, because their killing of fleeing men apparently offended British notions of fair play.

Speaker 5 I say, not very sporting to kill a man as he runs. But Lord Raglan issued no orders, and so all of the British forces simply looked on as this happened.

Speaker 5 So now the Russians controlled the Fadukian Heights, the Causeway Heights, and they had captured a bunch of British cannon that had been left behind by the fleeing Turkish soldiers.

Speaker 5 Not a very good start for the Brits. But then the Russians overplayed their hand a little bit.

Speaker 5 Their next move was to send the cavalry after one of the British encampments, a somewhat pointless goal, as there was no one in it at the time.

Speaker 5 However, while charging towards the camps, an entire company of southern Highlanders infantry popped out from behind a hill and lined up in a straight line.

Speaker 5 This little infantry action would become known as a thing of legend. It would forever be remembered as the thin red line.

Speaker 5 This would become a slang term used for the British Army in general for long after.

Speaker 5 Basically, horses love charging thin lines of men, but they don't like charging deep squares of men. So the thin red line looked pretty vulnerable to the Russians.

Speaker 5 But what the Russians didn't know was that the Brits had a secret weapon, the Enfield Rifled Musket, a gun that was considerably more powerful and more accurate than any other that had been on the battlefield to date.

Speaker 5 With one mighty volley, the thin red line was able to kill enough horsemen that the Russian commanders halted their charge and started to retreat.

Speaker 5 Now, this little moment may not seem like a big deal, but the thin red line kind of illustrates what was going on with the British Army at this time.

Speaker 5

You see, they had the most powerful army in the world. They were the best equipped.

They had the best weapons. And in many ways, they were the best trained.

They were just so poorly led.

Speaker 5

The leadership just didn't know the weapons they had in their hand. You know, the entire British force was kind of like an Enfield rifle.

Powerful, accurate.

Speaker 5 But it was in the hands of men who simply did not know how to use it.

Speaker 5 As the Russian cavalry retreated, Lord Raglan eventually got an order to the heavy brigade of the cavalry to charge these fleeing Cossacks.

Speaker 5 This first charge didn't actually achieve too much, but it did set the stage for what was about to occur.

Speaker 5 After the charge of the heavy brigade, the Russian cavalry retreated behind a battery of cannon on the far end of the valley between the Fedukian Heights and the Causeway Heights.

Speaker 5 Now this is where things get a bit dicey, and there's some disagreement between historians on these facts, so keep that in mind.

Speaker 5 It's the contention of some historians that the men of the Light Brigade were getting anxious, and many were eager to charge into battle.

Speaker 5 They had been kept out of the fight so far, and they had to watch the Cossacks cut down their Turkish allies and steal their cannon.

Speaker 5 They also had to sit immobile while the heavy brigade got to chase after them.

Speaker 5 Many of the accounts of the surviving members of the Light Brigade suggest that the writers were chomping at the bit to charge. They also had decided on a target, the Cossacks.

Speaker 5 Even though they were in the best defended position possible, the Light Brigade wanted revenge on those horsemen. All they needed was an excuse.

Speaker 5 This is when Lord Raglan issued his famously vague order.

Speaker 5 It read: Lord Raglan wishes the cavalry to advance rapidly to the front, follow the enemy, and try to prevent the enemy carrying away the guns. Troop, horse artillery may accompany.

Speaker 5

French cavalry is on your left. R.

Airy, immediate.

Speaker 5 Now, the problem with this order was that it was completely unclear which guns Raglan was referring to.

Speaker 5 Did he mean for the light brigade to head up to the causeway ridge and retake the guns that had been taken from them in the first place?

Speaker 5 Or was he referring to the well-defended battery of cannon where the Cossacks were hiding at the far end of the valley?

Speaker 5 Now, the common assumption about this event is that even though this order was completely unclear, the commanders on the ground were bound to it because questioning this order would be an act of insubordination.

Speaker 5 But that is just not true.

Speaker 5 It wasn't considered insubordination for a regiment commander to seek clarification or completely disregard an order if the realities on the ground had changed since that order was issued.

Speaker 5 Since all the orders had to be delivered by hand on slips of paper, a lot could change by the time an order was delivered.

Speaker 5 In fact, during the Battle of Belaclava, both Lord Lucan and Lord Cardigan had disregarded a number of orders that had come from Raglan, as they seemed out of touch with their present reality.

Speaker 5 They had every reason to seek clarification, but they didn't. Lord Lucan was first delivered the order, and then he carried it to his hated brother-in-law.

Speaker 5

Historian Terry Brighton tells us that their conversation went a little something like this. Lucan.

Lord Cardigan, you are to advance down the valley with the light brigade.

Speaker 5 I will follow in support with the heavy brigade. Cardigan.

Speaker 5

Certainly, sir, but allow me to point out to you that the Russians have a battery in the valley on our front and batteries of riflemen on both sides. Lucan.

I know it, but Lord Raglan will have it.

Speaker 5 We have no choice but to obey.

Speaker 5 End quote.

Speaker 5

But here's the thing. They did have a choice.

As Lord Cardigan pointed out in that quote, this charge was obviously suicidal.

Speaker 5 They would be charging through the valley between the Causeway Heights and the the Fidukian Heights, upon both of which were stationed Russian cannon, and they would be riding right into the mouths of yet more Russian guns.

Speaker 5 So basically, they would be shot at from every conceivable direction if they followed the order. So why did they do it?

Speaker 5 Well, there are three possible explanations.

Speaker 5 The first is the traditional explanation, and that's that Lucan and Cardigan were just so inexperienced and and so incompetent as commanders that they didn't realize exactly how bad the order was.

Speaker 5 They went for it out of a sense of chivalry and bravery and stupidity.

Speaker 5 Now, this interpretation has been challenged in recent years because, as our previous quote seemed to show, Lord Cardigan, for all his ridiculousness, did know that charging that position was a bad idea.

Speaker 5 So that brings us to our second explanation.

Speaker 5 This was that Lukan had misinterpreted the order, but the agitated light brigade were actively spoiling for a fight and were putting pressure on Cardigan and Lucan to go after the Cossacks.

Speaker 5 They had picked their target a long time before, and Raglan's order was all they needed to hear to set off on a death charge.

Speaker 5 In this reading, it was the rank and file of the light brigade themselves who pushed for the charge, and that couldn't be any more different than the Tennyson poem.

Speaker 5 The third explanation, and I kind of love this one, is that Lucan purposefully misread the order so he could send Cardigan to his death.

Speaker 5 The charge of the light brigade would just be an elaborate way to kill his hated brother-in-law. Now, that theory is pure speculation and it's not really backed up by any hard evidence.

Speaker 5 However, the feud between the two men makes it seem kind of possible. But in the end, whatever the reason was, the decision was made to charge.

Speaker 5 And Lord Cardigan, for all of his pettiness, actually mustered the courage to lead the charge himself. deep into the mouth of hell.

Speaker 5 But here's the craziest thing about the charge of the Light Brigade. It was actually kind of a success.

Speaker 5 Despite sustaining ridiculous losses while riding through an insane crossfire of cannonballs, the remains of the Light Brigade made it all the way across the valley and actually managed to catch the Cossacks flat-footed.

Speaker 5 They actually dealt out some serious punishment to the Russians. But here's the thing: the heavy brigade never arrived as promised.

Speaker 5 Lucan had pledged to Cardigan that he would follow behind with his forces, but instead he just sat safely on the other side of the valley.

Speaker 5 When the bulk of the Russian forces arrived to support the surprised Cossacks, the light brigade was forced to retreat.

Speaker 5 The retreat was yet another death ride back through the valley that was still being bombarded by Russian guns. So imagine this.

Speaker 5 The light brigade had to run the gauntlet all the way down, guns on three sides to get to the Cossacks.

Speaker 5 They get there, they deal out some death, they're not supported, they turn around only to run that gauntlet once again.

Speaker 5 By the end of the charge, 118 men were killed, 127 were wounded, and 60 were taken prisoner. And enough horses had died that the entire unit was basically lost.

Speaker 5 Still, Still, with 305 casualties, that means that well over half of the light brigade actually survived the attack, including our old buddy, Lord Cardigan, who somehow came out of it without a scratch.

Speaker 5 Apparently, after Cardigan reached the guns, he figured his duty was done and slowly started to creep back to the British lines, because apparently galloping would have seemed like he was a coward or something.

Speaker 5 So, how does the the myth line up with the facts? The myth tells us that the men were but noble pawns. The facts tell us that they were rowdy actors who may have influenced the decision to charge.

Speaker 5 The myth tells us that it happened because men followed orders without question.

Speaker 5 The facts tell us that orders were disregarded all the time, and this particular one really should have been.

Speaker 5 They only charged because either the men were restless, Lucan wanted Cardigan dead, or neither of the commanders wanted the trouble of clarifying an order.

Speaker 5 The myth would have us believe that every man in the light brigade died a glorious death, but in reality, the vast majority of the men survived the charge, and over half remained unwounded and still on their horses.

Speaker 5 The Battle of Belaclava would end as a bloody stalemate, and so too would the Crimean War. The British would eventually take Sevastopol, and the Russians did eventually sue for peace.

Speaker 5 But the cost of the war was so high that by the end, all of the countries involved had become thoroughly sick of the conflict.

Speaker 5 It had been a stupid war fought poorly by everyone involved, and its most memorable event is perhaps history's greatest military blunder.

Speaker 5 Tennyson's poem immortalized the men of the Light Brigade, but it also succeeded in teaching people the wrong lesson about the Crimean War. In Tennyson's poem, war is hell, but it's a glorious hell.

Speaker 5 It's a dark enterprise punctuated by the light of bravery.

Speaker 5 But the actual charge of the light brigade was just a mess of poor communication, rash decision-making, and potentially personal vengeance. It was war at its most senseless.

Speaker 5 In the end, the Crimean War would lead to reforms in the British military.

Speaker 5 The system of purchases would be changed, so the likes of Lucan and Cardigan would not be able to so easily rise through the ranks.

Speaker 5 However, aristocrats were able to flex their privilege in the military well into the First World War.

Speaker 5 Similarly, the cavalry would stick around into the Great War as well, until the realities of that horrific conflict swept it away.

Speaker 5 Interestingly enough, it would take the industrial carnage of World War I to finally take both the horses and the donkeys out of the British military forever.

Speaker 5 Okay,

Speaker 5

that's all for this week. Thanks again for listening.

First off, this week, before we go, I have to thank everyone who has been supporting the show on Patreon. I have been honored and humbled by this.

Speaker 5 And I'm going to give give my first shout outs to those of you who have supported at the $5

Speaker 5 or more level.

Speaker 5 So here's a shout out to Leo Sutton, to Digby, to Christina Honor, to Andrew Pearson, to Callum Montgomery, to Robert Morris, to Leah Metena, to Raz Howard, and to Samantha Marriage.

Speaker 5

You guys are the true heroes. Thank you so much.

And to everyone else that supported at the $3, $1 level or whatever support you've been giving, thank you so much.

Speaker 5 I also wanted to say that if anyone wants to support at the $5 or more level, but does not want their name read on the podcast, I totally get it. Just let me know.

Speaker 5 It's not like you're guaranteed to get your name read.

Speaker 5 So if you really do not want that option, just shoot me an email at ourfakehistory at gmail.com and I will not read your name if that is not not something that is enjoyable for you.

Speaker 5 Hopefully, everyone whose name I just read were totally into it.

Speaker 5 For everyone else out there, please consider supporting OurFake History on Patreon. Just go to patreon.com/slash our fake history,

Speaker 5 and you can support us on a monthly basis. The other best way to support the show is to buy our extra episodes.

Speaker 5 You can go to the website at ourfakehistory.com and click the link to buy the extra shows. Hopefully in the coming months, I'll have some time to create more extra content.

Speaker 5 And those of you supporting at $3 or more on Patreon, you are guaranteed to get any extra stuff that I make.

Speaker 5

This week, I also want to let everybody know that I have been moonlighting on you. I have appeared on another podcast.

I was just on a recent episode of This Is My Toronto.

Speaker 5 That's a new podcast coming out of my home city of Toronto, Ontario, Canada, hosted by Jeff McCartney. What Jeff is doing is he is interviewing musicians.

Speaker 5

entrepreneurs and historians from around the city of Toronto. So I sat down with him.

We had a great conversation.

Speaker 5 If you want to hear me ramble on about history, about my thoughts on Dan Carlin, about

Speaker 5 how I pick topics,

Speaker 5 if you just want to know more about me and about

Speaker 5 the show, go and check out This Is My Toronto. You can find it on iTunes, Stitcher, or any other podcast app.

Speaker 5 Jeff was a very gracious host and really made me feel welcome on his show. So I really encourage you to give it a shot.

Speaker 5 In the meantime, if you want to get in touch with me, you can shoot me an email at ourfakehistory at gmail.com. You can follow along on Twitter at Ourfake History.

Speaker 5

Or you can go to the Facebook page. Go to Facebook slash our fake history.

I'm going to have maps up. I'm going to have some pictures up of Lord Cardigan this week.

So check it out.

Speaker 5

It has been quite a week. I know that the podcast was a little late, and I apologize for that.

I don't like doing that. But, you know, world events have been bananas.

Speaker 5 And I guess all I have to say about that is that I love each and every one of you. And all I want to do is just put more love and good things out into the world.

Speaker 5 So, if this podcast is a good thing in your life,

Speaker 5

then that makes me greatly happy. And all I want is just for more positivity.

Okay, as always, the theme music comes to us from Dirty Church.

Speaker 5 You can check out dirty church at dirtychurch.bandcamp.com. And all the other music you heard on the show today was written and recorded by me.

Speaker 5 My name is Sebastian Major, and just remember, just because it didn't happen doesn't mean it isn't real.

Speaker 5 One, two, three, five.

Speaker 7 You're juggling a lot, full-time job, side hustle, maybe a family, and now you're thinking about grad school? That's not crazy. That's ambitious.

Speaker 7 At American Public University, we respect the hustle and we're built for it. Our flexible online master's programs are made for real life because big dreams deserve a real path.

Speaker 7 At APU, the bigger your ambition, the better we fit. Learn more about our 40-plus career relevant master's degrees and certificates at apu.apus.edu.

Speaker 1 Coach, the energy out there felt different.

Speaker 5

What changed for the team today? It was the new game day scratchers from the California Lottery. Play is everything.

Those games sent the team's energy through the roof.

Speaker 1 Are you saying it was the off-field play that made the difference on the field?

Speaker 5 Hey, little play makes your day, and today, it made the game. That's all for Coach, one more question.

Speaker 8 Play the new Los Angeles Chargers, San Francisco 49ers, and Los Angeles Rams Scratchers from the California Lottery. A little play can make your day.

Speaker 8 Please play responsibly, must be 18 years or older to purchase, play, or claim.