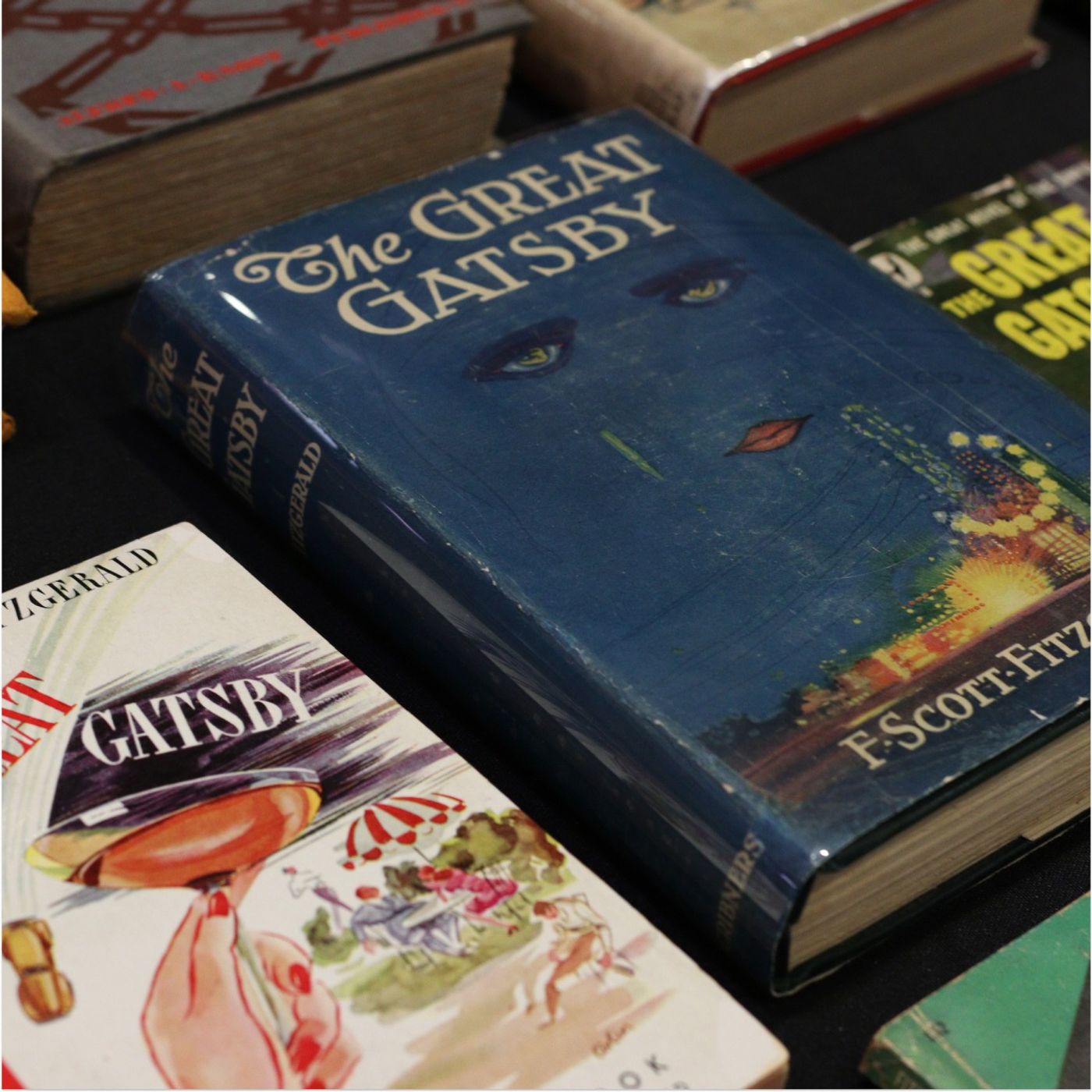

100 Years of ‘The Great Gatsby’

This year, “The Great Gatsby” turns 100.

A.O. Scott, a critic at large for The New York Times Book Review, tells the story of how an overlooked book by a 28-year-old author eventually became the great American novel, and explores why all of these decades later, we still see ourselves in its pages.

A.O. Scott, a critic at large for The New York Times Book Review, tells the story of how an overlooked book by a 28-year-old author eventually became the great American novel, and explores why all of these decades later, we still see ourselves in its pages.

Press play and read along

Transcript

Transcript is processing—check back soon.

The Daily — 100 Years of ‘The Great Gatsby’