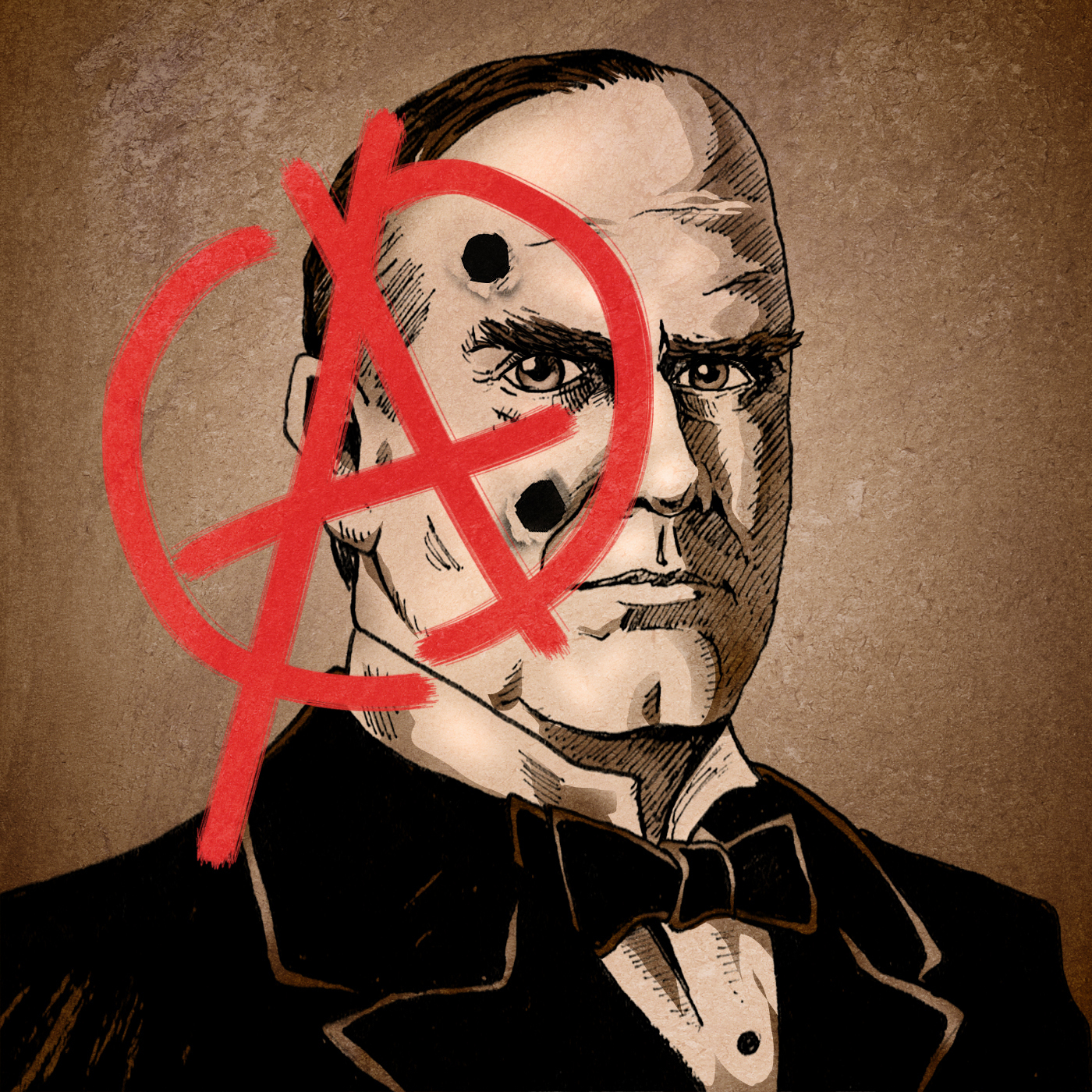

Episode #232 - Why President McKinley? (Part III)

It's impossible to assess the historical reputation of President William McKinley without tangling with the Spanish-American War. In this final part of the William McKinley trilogy Sebastian gets into the debate around what actually lead to the war. Could a war with Spain have been avoided? Was McKinley pushed into it by a manipulative American press? How did the outcome of the "splendid little war" change America, McKinley, and the world? Tune-in and find out how jingoes, yellow journalism, and the worst-timed naval accident in history all play a role in the story.

See Privacy Policy at https://art19.com/privacy and California Privacy Notice at https://art19.com/privacy#do-not-sell-my-info.

Press play and read along

Transcript

Transcript is processing—check back soon.

Our Fake History — Episode #232 - Why President McKinley? (Part III)