Episode #231 - Why President McKinley? (Part II)

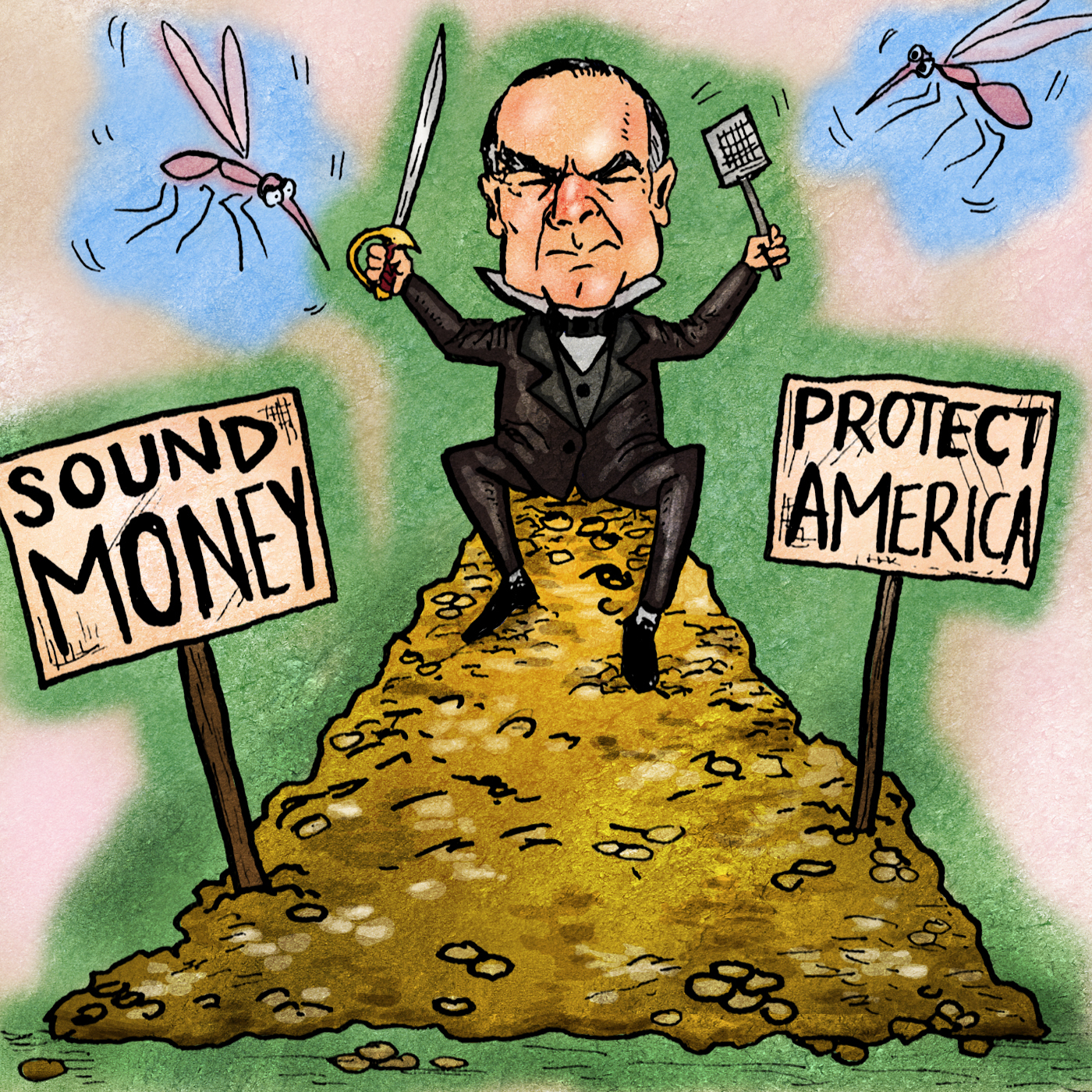

The 1896 election of William McKinley has been noted as an inflection point in American politics. But, historians are often conflicted about what story they want to tell. It could be seen as moment when Americans rejected a populist firebrand, critical of the wealthy and appealing to working class consciousness. It could also be seen as the moment when American industrialists, bankers, and other monied interests took an activist role in American politics. Was William McKinley simply a puppet of "big money" or is there more to this story? Tune-in and find out how king-makers, front porch campaigns, and crucifixion on a cross of gold all play a role in the story.

Visit Rosettastone.com/HISTORY to get started and claim your 50% off TODAY!

See Privacy Policy at https://art19.com/privacy and California Privacy Notice at https://art19.com/privacy#do-not-sell-my-info.

Press play and read along

Transcript

Speaker 1 Audival's romance collection has something to satisfy every side of you. When it comes to what kind of romance you're into, you don't have to choose just one.

Speaker 1 Fancy a dallions with a duke, or maybe a steamy billionaire. You could find a book boyfriend in the city and another one tearing it up on the hockey field.

Speaker 1 And if nothing on this earth satisfies, you can always find love in another realm. Discover modern rom-coms from authors like Lily Chu and Allie Hazelwood, the latest romanticy series from Sarah J.

Speaker 1 Maas and Rebecca Yaros, plus regency favorites like like Bridgerton and Outlander. And of course, all the really steamy stuff.

Speaker 1 Your first great love story is free when you sign up for a free 30-day trial at audible.com slash wondery. That's audible.com/slash wondery.

Speaker 2

You're juggling a lot. Full-time job, side hustle, maybe a family, and now you're thinking about grad school? That's not crazy.

That's ambitious.

Speaker 2 At American Public University, we respect the hustle and we're built for it. Our flexible online master's programs are made for real life because big dreams deserve a real path.

Speaker 2 At APU, the bigger your ambition, the better we fit. Learn more about our 40-plus career relevant master's degrees and certificates at apu.apus.edu.

Speaker 3 Here's a fun question for you.

Speaker 3 Would you rather be the king or the king maker?

Speaker 3 Are you the kind of person that likes sitting in the big seat, being the face of the operation, wearing the crown, and marching in the parade in a place of honor?

Speaker 3 Or would you rather stand to the side, wield power quietly, planting seeds and tending the ground so that your vision ultimately bears fruit?

Speaker 3 The Kingmaker role comes with less fame and accolades, perhaps, but there's a certain type of quiet authority that comes with knowing that you are the power behind the throne.

Speaker 3 Now, it's perfectly understandable if neither of these roles appeal to you. In fact, that might be very healthy.

Speaker 3 But this week, we are talking about politics, and in politics, ambition is just part of the water in which we swim.

Speaker 3 And politics is filled with people who either want to be the king or want to be the kingmaker.

Speaker 3

You see, one of the big debates around the legacy of U. S.

President William McKinley is how much he was influenced, beholden to, or even puppeted by the powerful men who supported him.

Speaker 3 You see, in the William McKinley story there is a kingmaker, or perhaps it's fairer to call him an alleged kingmaker. This was a man named Marcus Alonso Hanna.

Speaker 3 Hanna was an Ohio-born businessman who, after a number of fairly disastrous false starts, eventually built a small business empire in Cleveland that involved coal, iron, and shipping on the Great Lakes.

Speaker 3 He was a millionaire by the age of 40, and after that, he threw himself energetically into politics.

Speaker 3 He gravitated to the Republican Party, where he gained a reputation for being an effective behind-the-scenes operator.

Speaker 3 He was the kind of political organizer and strategist who was good at fundraising and knew how to whip up support for a particular candidate.

Speaker 3 He was a persuasive backroom negotiator, which, of course, gave rise to rumors that he wasn't above using his wealth or the wealth of his donors to grease palms in order to get things done.

Speaker 3 Now, most historians are careful to point out that there's little evidence that Hanna was involved in the blatant type of money for favors corruption that he was often accused of by his political opponents, but there's no doubt that he was effective at marshalling the wealth of others and putting it to work for political purposes.

Speaker 3 Neither Mark Hanna nor William McKinley could remember exactly when they met, but by 1888 the men were working together closely, with Hannah managing McKinley's ultimately unsuccessful campaign to become the Speaker of the House of Representatives.

Speaker 3 This may not have been an auspicious start, but it launched a sturdy political alliance between the two men that culminated in McKinley becoming President of the United States.

Speaker 3 In many ways, McKinley and Hannah were very different political animals. McKinley was principled, plain-spoken, and loyal to the point of being inflexible.

Speaker 3 Hannah was a much more slippery figure, who was pragmatic, critics would say, unscrupulous, when it came to achieving political goals.

Speaker 3 McKinley biographer Margaret Leach, writing in the late 1950s, believed that Hannah was actively drawn to McKinley because he brought with him an air of respectability that Hannah craved.

Speaker 3 She would write, quote, cynical in his acceptance of contemporary political practices, Hannah was drawn to McKinley's scruples and idealistic standards, like a hardened man of the world who becomes infatuated with virgin innocence, end quote.

Speaker 3 I kind of like that.

Speaker 3 Indeed, the differences between these two figures was not lost on many contemporary political observers.

Speaker 3 Critics sometimes cast Hannah as a devilish figure who had corrupted William McKinley with his access to big donor money.

Speaker 3 A political cartoon published in the New York Journal in 1896 summed up this perception neatly.

Speaker 3 The portly Mark Hanna was shown wearing a suit made from dollar bills and brandishing a whip while a skull labeled labor lay at his feet.

Speaker 3 Tucked into his belt was a tiny, helpless William McKinley, around his big toe a tag that labels the future president property of the syndicate.

Speaker 3 In the cartoonist's estimation, McKinley had been sold by Hannah to the moneyed men behind the Republican Party.

Speaker 3 The question is: how fair was that caricature?

Speaker 3 Was McKinley a puppet of Hannah and his well-heeled donors? Or was that little more than political slander meant to discredit an otherwise honest and forthright politician?

Speaker 3 After 1888, Hannah became one of McKinley's most essential political advisers and campaign strategists.

Speaker 3 He helped revive the congressman's political career after being ousted in the wake of his unpopular tariff bill.

Speaker 3 He helped the major, as McKinley liked to be called, receive the Ohio State Republican nomination for governor and then win the election for that office in 1891 and then re-election in 1893.

Speaker 3 Ohio governors only served two-year terms back then.

Speaker 3 When McKinley ran for president in 1896, Hannah was instrumental in that successful campaign.

Speaker 3 But the relationship between McKinley and Hannah, or to put an even finer point on it, McKinley and money, has divided his biographers and other historians of this period.

Speaker 3 Many biographers have pushed back on the idea that McKinley took any kind of direction from Hannah or anyone else. Defenders claim that he was not the kind of man who could be bought.

Speaker 3 He was simply too principled to become a corporate stooge.

Speaker 3 However, other historians aren't so sure.

Speaker 3 There were some key moments in McKinley's life when large influxes of money from wealthy Americans and in some cases, corporations drastically altered his political fortunes.

Speaker 3 McKinley's relationship with corporate America might be one of the keys to understanding his somewhat unexpected, recent resurgence as a president of note.

Speaker 3 For many decades, McKinley's fairly middling presidential reputation was bolstered by the idea that he was an ineffectual puppet.

Speaker 3 It seemed in keeping with what Teddy Roosevelt called his, quote, chocolate eclair backbone.

Speaker 3 Recent biographies have tried to push back against that image, but have they pushed too hard?

Speaker 3 In the attempt to reclaim McKinley, have some biographers been too quick to skate past difficult questions of how beholden McKinley was to his political donors?

Speaker 3 Let's see if we can pick it apart today on our fake history.

Speaker 3 Episode number 231, Why President McKinley, Part 2.

Speaker 3 Hello and welcome to Our Fake History.

Speaker 3 My name is Sebastian Major, and this is the podcast where we explore historical myths and try to determine what's fact, what's fiction, and what is such a good story. It simply must be told.

Speaker 3 Before we get going this week, I just want to remind everyone listening that an ad-free version of this podcast is available through Patreon.

Speaker 3 Just head to patreon.com slash our fake history and start supporting at $5 or more every month to get access to an ad-free feed and a huge list of extra episodes, including the new two-hour-long patron-requested exploration of the Bronze Age collapse.

Speaker 3 This podcast keeps on going thanks to the generous support of the patrons.

Speaker 3 So, if you want to support the show and get access to a ton of awesome extras, then please head to patreon.com/slash/ourfakehistory and see what level of support works for you.

Speaker 3

This week, we are returning to the late 19th century to explore the political career of U.S. President William McKinley.

This is part two of what is going to be a trilogy of episodes.

Speaker 3 So if you've not heard part one, then I strongly suggest you go back and give that a listen now.

Speaker 3 In the first part, I did my best to explain why the relatively obscure President McKinley deserves the Our Fake History treatment.

Speaker 3 Like many of you, I was more than a little surprised when McKinley started appearing favorably in speeches made by Donald Trump.

Speaker 3 When the 47th president declared that Alaska's highest peak was going to be renamed Mount McKinley in honor of the turn of the century commander-in-chief, it was clear to me that McKinley's historical reputation had recently gone through a remarkable transformation.

Speaker 3 The question was why?

Speaker 3 Then I learned that one of the most recent biographies of McKinley was written by the controversial Republican political strategist Carl Rove,

Speaker 3 and a larger pattern started to reveal itself.

Speaker 3 There seems to be a concerted effort by certain contemporary Republicans to revive McKinley's image.

Speaker 3 For decades, McKinley was largely written off by historians as a middling, weak-willed president overshadowed by his successor, Teddy Roosevelt.

Speaker 3 Roosevelt's scathing assessment that McKinley had the backbone of a chocolate eclair was often used as the final word on McKinley's character and his time as president.

Speaker 3 So, while there certainly was room to bring more nuance to the popular understanding of McKinley, it seems curious that modern Republicans like Karl Rove were so enthusiastic about a president who represented a very different version of the Republican Party than the one that exists today.

Speaker 3 It was only after spending quite a lot of time reading about McKinley that his appeal to recent biographers became clearer to me.

Speaker 3 In part one of this series, we looked at McKinley's early life in Ohio and explored his origins in a family composed of both wealthy industrialists and committed anti-slavery advocates.

Speaker 3 We saw how he made a name for himself as an officer in the Union Army during the Civil War and earned the rank of Brevet Major, which is why friends and admirers took to calling McKinley the Major.

Speaker 3 From there, we saw how McKinley parlayed a successful legal career in Canton, Ohio into a political career as a Republican Ohio congressman.

Speaker 3 As we explored in the last episode, part of the reason McKinley has been back in the news is that as a congressman, he was a loud proponent of protective tariffs.

Speaker 3 As it turns out, tariffs were just as controversial in the 1890s as they are now.

Speaker 3 At the peak of his congressional career, McKinley became the chairman of the House Ways and Means Committee.

Speaker 3 and in that role helped author one of the most expansive packages of tariffs in the nation's history.

Speaker 3 This gave me an opportunity to speak on who exactly supported and who rejected high tariffs in the late 19th century.

Speaker 3 Wealthy industrialists and manufacturers trying to get an edge on their European rivals generally liked protective tariffs, while small farmers, artisans, and people who exported agricultural products did not support the policy.

Speaker 3 I also tried to point out that McKinley's tariffs were specifically designed to reduce government income.

Speaker 3 As you might remember, the American government was running a surplus that was bad for the economy in the late 19th century. Go figure.

Speaker 3 High tariff rates actually brought down the amount of money that the American government was bringing in through this form of taxation.

Speaker 3 The lesson here is: if you want your tariffs to protect domestic businesses, then they cannot also be a money maker for the government.

Speaker 3 To protect the businesses, you have to set your tariff rate so high that imports decrease, and as such, the taxes collected from tariffs also decrease.

Speaker 3 When we left off, we saw that a fresh financial panic and an economic recession in 1890 cost the Republican Party in that year's midterm elections.

Speaker 3 The tariff bill was seen as contributing to the economic calamity, but the truth was that it had barely taken effect before the economic winds changed.

Speaker 3 The tariffs neither saved the American economy nor did they stem the coming depression. The tariffs were a mixed bag at best.

Speaker 3 Assessing just how successful William McKinley's tariff policy was is tricky because so much of his bill was later revised, Republicans would say, watered down, by the successive Democratic Congress.

Speaker 3 So, with that in mind, any grandiose claims that tariffs made America very rich in the 1890s should be taken with a healthy dose of salt.

Speaker 3 But while I wanted to use this series to better put the tariff issue into historical context, I don't think the recent fascination with William McKinley can entirely be be explained by the misunderstanding, or perhaps cynical oversimplification, of his tariff policies.

Speaker 3 I believe that part of that has to do with what Warren Zimmerman calls the

Speaker 3 tantalizing enigma of William McKinley.

Speaker 3 The word many biographers use to describe McKinley's personality is stolid.

Speaker 3 That's a slightly old-fashioned piece of vocabulary that means calm, dependable, and showing little emotion or animation.

Speaker 3 Someone less kind might even call McKinley boring.

Speaker 3 Interestingly, this became a key part of his political brand. He presented himself as a reasonable, thoughtful man who is principled without being overly ideological.

Speaker 3 In certain political cycles, being the boring, but presumably safe choice can can pay dividends.

Speaker 3 But this means that it's easy to project onto William McKinley whatever you want.

Speaker 3 His stolid personality and political style have left room for various generations of historians and biographers to fill in the blanks.

Speaker 3 Through McKinley, you can tell a story about America embracing its role as an economic powerhouse and an honest-to-goodness imperial world power.

Speaker 3 McKinley can be cast as the steady hand at the wheel who helped America through its growing pains to emerge as a superpower ready to challenge the European empires for world hegemony.

Speaker 3 Or, McKinley could be presented as a man out of his depth, swamped by the money of America's corporate oligarchs, and unable to resist the forces hungry for war and the fruits of empire.

Speaker 3 A given biographer's biographer's feelings about imperialism, American overseas acquisitions, and the role of money in politics will deeply affect how he or she presents William McKinley.

Speaker 3 When it comes to how McKinley first became President of the United States in 1896, you can really see the differences in the sources.

Speaker 3 So, as we go, I'm going to do my best to highlight those differences in the various histories that I have read.

Speaker 3 So, let's jump back into the William McKinley story and see what we can learn about his road to the White House.

Speaker 3 Today's episode of Hour Fake History is being brought to you by Progressive Insurance.

Speaker 3 Do you ever find yourself playing the budgeting game, shifting a little money here, a little there, and hoping it all works out?

Speaker 3 Well, with the Name Your Price tool from Progressive, you can be a better budgeter and potentially lower your insurance bill too.

Speaker 3 You tell Progressive what you want to pay for car insurance and they'll help you find options within your budget. Try it today at progressive.com.

Speaker 3

Progressive Casualty Insurance Company and Affiliates. Price and coverage match limited by state law.

Not available in all states.

Speaker 3

Today's episode of Our Fake History is being brought to you by Audible. Now, I love it when Audible supports the show because I actually use Audible.

No joke.

Speaker 3 I use the service all the time to research this podcast.

Speaker 3 Those of you that listen know that I plow through books to research this show, and it's really helpful to be able to listen to some of those books.

Speaker 3 Well, Audible is the service that lets you enjoy all of your audio entertainment in one app.

Speaker 3 They have the best selection of audiobooks without exception, along with popular podcasts and exclusive Audible originals.

Speaker 3 Over the past few months, I listened to The Bronze Lie by Mike Cole to get ready for this series on Sparta. I also listened to Deirdre Bear's Al Capone biography on Audible.

Speaker 3 I also love the great courses lecture series that are available through Audible. I often go to those lecture series to get an overview of a particular topic that I'll be covering on this show.

Speaker 3

For real, guys, I'm a fan. Start listening and discover what's beyond the edge of your seat.

New members can try Audible now for free for 30 days and dive into a world of new thrills.

Speaker 3 Visit audible.com/slash OFH or text OFH to 500-500. That's audible.com/slash OFH or text OFH to 500-500.

Speaker 3 William McKinley's loss in the 1890 congressional midterms turned out to be just a temporary setback for the major.

Speaker 3 Many Republicans had started to take notice of the Ohio politician as a rising star in the party, and many were eager to see him remain active in politics.

Speaker 3 So it was that just a year after being ousted from the House of Representatives, McKinley pulled off a successful campaign to become the governor of Ohio.

Speaker 3 Given that Ohio was such a strategically important swing state at the time, the governorship of the state had become an important springboard towards the presidency.

Speaker 3 McKinley proved to be a fairly popular governor of the state, which was especially significant given how evenly divided the population was between Republican and Democrat sympathies.

Speaker 3 Ohio elections were typically very tight, but McKinley handily won his first term as governor by a margin of around 20,000 votes, which in the 1890s was quite large.

Speaker 3 This popularity reflected McKinley's ability to speak to the needs of Ohio's agricultural and manufacturing sectors. He was an unabashedly pro-business politician, but he wasn't overtly anti-labor.

Speaker 3 He sought compromise with unions and other labor organizations whenever he could.

Speaker 3 However, just before seeking re-election in 1893, William McKinley found himself embroiled in an embarrassing financial debacle.

Speaker 3 In that year, one of McKinley's old friends, an industrialist named Robert L. Walker, got himself into a financial disaster which nearly swallowed McKinley.

Speaker 3 You see, Walker had been an early supporter of William McKinley's political career.

Speaker 3 He had helped pay for McKinley's studies at Albany Law School and had contributed a healthy $2,000 to each of McKinley's congressional campaigns.

Speaker 3 As such, the major felt obligated to help his friend out when he got into some financial trouble. This started with McKinley co-signing a number of loans for Walker.

Speaker 3 However, Walker got himself terribly overextended and started presenting McKinley with documents that he said were routine loan extensions that he needed McKinley to sign off on.

Speaker 3 But it turned out that this was a bit of a scam.

Speaker 3 The overly trusting McKinley didn't realize that he was actually signing what were known as notes in blank, which allowed Walker to borrow more money with McKinley signed on as the guarantor.

Speaker 3 In 1893, yet another financial panic swept through the United States, plunging the economy into an even deeper depression.

Speaker 3 This proved to be the financial deathblow for Walker, who declared bankruptcy, leaving McKinley holding the bag for all of his bad debts.

Speaker 3 When it was all tallied, it was determined that William McKinley was on the hook for over $130,000,

Speaker 3 which would be the equivalent of owing $3.5 million

Speaker 3 today.

Speaker 3 This was roughly three times more than McKinley's net worth and could have ruined him.

Speaker 3 But the major was saved, or rather, his political career was saved by a coterie of wealthy friends and a handful of American businesses.

Speaker 3 You see, McKinley could have resigned as governor and as biographer Robert Mary puts it, quote, addressed the financial crisis without much exertion by abandoning politics and becoming a railroad lawyer or joining a prestigious law firm in New York or Chicago, end quote.

Speaker 3 McKinley needed outside help only if he was going to remain a politician, and there were clearly many people who wanted him to stay in politics.

Speaker 3 Specifically, the Cleveland lawyer Myron Herrick, the Chicago businessman and newspaper publisher Herman Colesat, and McKinley's wealthy strategist Mark Hanna.

Speaker 3 These three men directed his rescue. They created a trust that bought up all of McKinley's bad debt to insulate the McKinleys and protect the family assets from being seized.

Speaker 3 Then they set out to collect money from anyone who felt obliged to help out one of the Republican Party's most popular governors.

Speaker 3 There were some average Americans who felt like kicking in, but as biographer Scott Miller puts it, quote, the power brokers ultimately saved him, end quote.

Speaker 3

For instance, the Illinois Steel Company contributed $10,000 to the trust. Charles Taft, owner of the Cincinnati Times, gave $1,000.

Steel magnate Henry Clay Frick contributed $2,000.

Speaker 3 Railway car manufacturer George Pullman contributed $5,000, as did Chicago meat packing king Philip Armour. Within a few months, the trust had settled the debt, leaving McKinley forever grateful.

Speaker 3 So, here's the question. How should we interpret this moment in McKinley's life?

Speaker 3 For many of his contemporary political opponents, this was the moment when McKinley was bought.

Speaker 3 This is when the caricatures of McKinley literally being in the pockets of American moneyed interests began to be circulated.

Speaker 3 Biographers like Scott Miller underscore this financial crisis as a moment when McKinley lost some of his credibility.

Speaker 3 Now, whether or not he took his marching orders from his wealthy donors, there's no denying that he was in their debt from that point on.

Speaker 3 And in Scott Miller's biography, he stresses just how much further McKinley would go down that road.

Speaker 3 Biographer Robert Mary is a bit more measured, pointing out that McKinley's, quote, need to avail himself to the comfort of rich friends with large financial stakes in government actions generated the view among some that he was a puppet of plutocrats.

Speaker 3 However, Mary ultimately points out that, quote, McKinley's image as a man of rectitude and quiet wisdom seemed to fortify him politically, end quote.

Speaker 3 Interestingly, Carl Rove presents this crisis as not in the least bit compromising for McKinley.

Speaker 3 In his book, Rove emphasizes that McKinley was helped by friends who McKinley praised for their quote noble generosity.

Speaker 3 Rove is vague about where McKinley's bailout money came from, choosing to omit the names of specific businesses and the well-known industrialists who contributed to the trust.

Speaker 3 Rove caps his summary of this episode by quoting friendly newspaper reports that declared McKinley to be a, quote, honest and honorable man who got in trouble through doing a kindness to a friend, end quote.

Speaker 3 Rove notably does not include any of the more critical assessments of McKinley's millionaire-backed bailout.

Speaker 3 Now,

Speaker 3 why do this, Carl Rove? Why not give us the full picture?

Speaker 3 Once again, a sticky McKinley moment is soft-pedaled in that particular biography.

Speaker 3 Now, to be fair, I am focusing on a very small matter of emphasis here, but it's clear that throughout Karl Rove's book, he makes choices that keep McKinley looking good, or at the very least, uncompromised.

Speaker 3 Still, while this millionaire bailout would remain an embarrassment exploited by political opponents, it clearly did not overly concern the American electorate.

Speaker 3 Later that year, McKinley cruised to an easy reelection as Ohio's governor, receiving the largest percentage of the vote of any Ohio governor since the Civil War.

Speaker 3 McKinley's reelection confirmed his status as one of the most important Republicans in the country and a likely contender to be the next Republican nominee for President of the United States.

Speaker 3 So it was that in 1895, McKinley started actively pursuing the Republican nomination for president. On the case was, of course, Marcus Hanna.

Speaker 3 Now, very early on, it became clear that William McKinley was broadly popular within the party and that there were few other viable challengers for the 1896 nomination.

Speaker 3 This meant that McKinley didn't have to play ball with the so-called Republican Party bosses.

Speaker 3 These were well-connected Northeastern politicians who who could reliably deliver large blocks of delegates at the party convention.

Speaker 3 Typically, if you wanted to win the nomination, you needed to make a deal with these bosses. If the bosses supported you, they would usually want a say in policy or some plum political appointments.

Speaker 3 But McKinley's popularity was such that he and Hannah realized that they could get the nomination even without the bosses' support.

Speaker 3 They also cleverly branded their campaign for the nomination as McKinley versus the bosses, or sometimes the people versus the bosses.

Speaker 3 Now, this little slogan sometimes gets misconstrued as McKinley dabbling with populism. The people versus the bosses can sound like a slogan that a union organizer might use.

Speaker 3 But make no mistake, McKinley was not talking about the bosses of industry. Still, this little slogan is worth noting because it points to McKinley's great talent as a politician.

Speaker 3 As historian Hal Williams points out, McKinley had a deep belief in, quote, industrialism, central authority, and expansive capitalism, end quote.

Speaker 3 But he also knew how to appeal to workers, small farmers, and those often exploited by said expansive capitalism.

Speaker 3 Employing the slogan, the people versus the bosses, in a context where no actual bosses might get the impression that McKinley was a real reformer, is an example of his political maneuvering.

Speaker 3

In the end, those Republican political bosses were unable to stop McKinley's nomination in 1896. At the Republican convention in St.

Louis that year, he decisively locked down the nomination.

Speaker 3 However, the general election was quickly shaping up to be an uphill battle for the Republicans. America was once again in the grips of an economic depression.

Speaker 3 This had only gotten worse under the presidency of the Democrat Grover Cleveland, which at first seemed to bode well for the Republicans.

Speaker 3 When things go bad under a Democrat, usually the Republicans reap the political benefits.

Speaker 3 But in the context of of these tough economic times, a long-simmering debate around monetary policy was about to become the defining election issue.

Speaker 3 It would remake America's political fault lines and would fracture party unity among both the Democrats and the Republicans.

Speaker 3 The debate was around American currency.

Speaker 3 Now, forgive me if 19th century monetary policy is very much your jam, because I'm going to try and keep this explanation of a very complicated issue as concise as I can.

Speaker 3 Ever since the Civil War, the United States had been tinkering with its money supply, sometimes favoring gold coins and bills that could be redeemed for gold, known as the gold standard, and sometimes issuing currency as silver coins and making bills redeemable in that metal.

Speaker 3 At other times, like during the Civil War, the Treasury just printed greenbacks that were not necessarily connected to either metal.

Speaker 3 The gold standard tended to be favored by bankers, industrialists, and people who held a lot of wealth.

Speaker 3 Keeping American dollars pegged to gold kept their value stable, and it also helped resist inflation.

Speaker 3 However, it also kept the money supply tight, as the amount of cash in circulation could not outpace the amount amount of gold needed to back it up.

Speaker 3 So when a depression hit, like in the mid-1890s, you could get a situation where deflation occurred. That meant that products were being sold for lower prices than they had been previously.

Speaker 3 In 1896, the people hardest hit by deflation were America's farmers. Sure, a dollar could buy more, but the crops were being sold for fewer dollars.

Speaker 3 This was especially worrying if you were someone with a mortgage or who was otherwise carrying debt. Many of America's small farmers had mortgages or were deeply in debt at this time.

Speaker 3 Deflation meant that it was harder for those farmers to bring in the money that they needed to pay their debts.

Speaker 3 At this point in history, central banks did not set interest rates for the entire country. So just because there was a financial downturn didn't mean that an interest rate change was coming.

Speaker 3 Every bank could set their own rate. Many farmers found themselves in a position where they were unable to sell enough food to bring in enough money to service their debts.

Speaker 3 Some saw silver as the remedy for this. By issuing silver coins and making paper money money redeemable in silver, that would put more money into circulation, which would create inflation.

Speaker 3 The idea was that this would be good for the indebted farmer, as the price of the goods he was selling would rise, and the value of his debts would shrink.

Speaker 3 It was also argued that the value of silver was directly linked to the price of wheat.

Speaker 3 If the American government started buying more silver to press more coins, that would send the value of silver up, which apparently would lead to the price of wheat going up.

Speaker 3 Now, as it turned out, the connection between wheat prices and silver prices was not as rock solid as the campaigners would have people believe.

Speaker 3 But that was the pitch, and it clearly resonated with many farmers across the United

Speaker 3 This created a new fault line in American politics between the so-called gold bugs and the silverites.

Speaker 3 The gold bugs were accused of greedily protecting the value of their hoarded wealth at the expense of the indebted American farmer.

Speaker 3 On the other side, silverites were accused of gambling with America's money supply by causing inflation that could get out of control.

Speaker 3 Now, this issue did not fall neatly along party lines. Republicans tended to favor the gold standard, but to varying degrees.

Speaker 3 There were some straight-up silver Republicans, especially in the American West, where there were both farms and silver mines.

Speaker 3 The Democrats generally favored silver in this period, but there were many gold Democrats, especially in the American Northeast and in the Midwestern manufacturing hubs.

Speaker 3 After a very contentious and fractious convention in 1896, the Democrats nominated the 36-year-old silverite firebrand William Jennings Bryan.

Speaker 3 Bryan was an unequivocal supporter of silver currency and framed the issue as a battle between the American masses and the moneyed elites. You know, you might even say the people versus the bosses.

Speaker 3 Brian was young as far as national politicians went, but he was an undeniably gifted speaker, giving him the nickname the boy orator.

Speaker 3 At the Democratic convention, he clinched the nomination after delivering his famous cross of gold speech.

Speaker 3 In that speech, he not only made the case for silver currency, but he also proposed a decidedly populist and economically progressive understanding of the American economy.

Speaker 3 He declared, quote, the man who is employed for wages is as much a businessman as his employer.

Speaker 3 The farmer who goes forth in the morning and toils all day, who begins in spring and toils all summer, and who by the application of brain and muscle to the natural resources of the country creates wealth, is as much a businessman as the man who goes upon the board of trade and bets upon the price of grain.

Speaker 3 The miners who go down thousands of feet into the earth or climb 2,000 feet upon the cliffs and bring forth from their hiding places the precious metals to be poured into the channels of trade are as much businessmen as the few financial magnates who, in the back room, corner the money of the world.

Speaker 3 End quote.

Speaker 3 Without quoting any socialist thinkers, Brian was making the case that wealth came from labor.

Speaker 3 He then brought the speech to a climax by saying, quote, you shall not press down on the brow of labor this crown of thorns. You shall not crucify mankind upon a cross of gold, end quote.

Speaker 3 The effect of the speech was apparently so overwhelming that he overcame the holdouts at the Democratic Convention and secured the nomination.

Speaker 3 The speech was widely considered one of the greatest pieces of oratory from the 1890s.

Speaker 3 It was reprinted and widely distributed throughout the United States, giving Bryan an early edge in the general election.

Speaker 3 Now,

Speaker 3 if I may editorialize, the William Jennings Bryan part part of this story, I think, helps us understand why some biographers see this moment and this election as so pivotal.

Speaker 3 As I mentioned in the last episode, the 19th century Republican and Democratic parties did not neatly map onto what we would consider the left and right of the modern political spectrum.

Speaker 3 But 1896 is a bit of an inflection point.

Speaker 3 The nomination of Bryan saw the Democratic Party embrace a decidedly bottom-up understanding of how wealth was generated.

Speaker 3 The Republicans, at least in 1896, firmly rejected this. In this way, both major American political parties started gravitating towards different ends of the political spectrum.

Speaker 3 You could argue that our modern dynamic starts here.

Speaker 3 When the early polls came back after the Republican and Democratic conventions, it seemed like Bryan had an early edge in the contest for president.

Speaker 3 He was a persuasive speaker with a dynamic presence.

Speaker 3 The silver issue was also clearly resonating with many Americans, especially in crucial swing states like McKinley's, Ohio, and other parts of the Midwest.

Speaker 3 McKinley was also slow out of the gate and was not particularly interested in talking about the currency issue.

Speaker 3 In truth, he found the currency debate divisive and seemed genuinely unsure if a pure gold standard or some kind of gold-silver compromise was the best way forward.

Speaker 3 One gold-supporting magazine openly lamented that, quote, McKinley's character is vague and so little forecast of what he is likely to do can be got from either his career or or language that a good deal of uncertainty must mark the first year or two of his administration.

Speaker 3 ⁇

Speaker 3 Despite the excitement in the electorate over the gold versus silver issue, McKinley really did not want to talk about it. Instead, he wanted to make the campaign about his favorite issue, tariffs.

Speaker 3 It was in this context of wanting to avoid the key campaign issue that he uttered his famous line, quote, I'm a tariff man standing on a tariff platform, end quote.

Speaker 3

He followed that by saying, quote, this money matter is unduly prominent. In 30 days, you won't hear anything about it, end quote.

He would be wrong about that.

Speaker 3 When the 1896 campaign started, McKinley was down in the polls.

Speaker 3 The Democratic candidate was a young, energetic campaigner for the little guy who was delivering speeches to massive crowds around the country.

Speaker 3 McKinley, on the other hand, didn't want to leave Canton, Ohio, and was stubbornly insisting that this election needed to be about tariffs.

Speaker 3 So, how the heck did this guy win?

Speaker 3 Well, let's take a quick break and then we'll find out.

Speaker 3 Today's episode of Our Fake History is being brought to you by Rosetta Stone.

Speaker 3 Whether you're traveling abroad, planning a staycation, or just shaking up your routine, what better time to dive into a new language?

Speaker 3 With Rosetta Stone, you can turn downtime into meaningful progress.

Speaker 3 One feature of Rosetta Stone that I think is really cool is something called true accent, which helps you learn a language in the accent that people who speak it actually use.

Speaker 3

You can learn anytime, anywhere. Rosetta Stone fits your lifestyle with flexible on-the-go learning.

You can access lessons from your desktop or mobile app, whether you have five minutes or an hour.

Speaker 3

It's an incredible value to learn for life. A lifetime membership gives you access to all 25 languages, so you can learn as many as you want whenever you want.

Don't wait.

Speaker 3

Unlock your language learning potential now. Our fake history listeners can grab Rosetta Stone's lifetime membership for 50% off.

That's unlimited access to 25 language courses for life.

Speaker 3

Visit rosettastone.com slash history to get started and claim your 50% off today. Don't miss out.

Go to rosettastone.com slash history and start learning today.

Speaker 3

You want your master's degree. You know you can earn it, but life gets busy.

The packed schedule, the late nights, and then there's the unexpected. American Public University was built for all of it.

Speaker 3 With monthly starts and no set login times, APU's 40-plus flexible online master's programs are designed to move at the speed of life. You bring the fire, we'll fuel the journey.

Speaker 3 Get started today at apu.apus.edu.

Speaker 3 Many of the more recent McKinley biographers begin their books with a stated intention to put McKinley back in the center of his story.

Speaker 3 The argument goes that McKinley has been caricatured as a well-meaning but ultimately ineffectual figurehead who was led by the nose by his advisors.

Speaker 3 I think most modern biographers have done a good job of demonstrating that William McKinley was not really bossed around by anyone, including the supposed kingmaker Mark Hanna.

Speaker 3 In fact, Scott Miller has pointed out that, quote, Hannah acted just a shade obsequious in McKinley's presence, end quote.

Speaker 3 Trusted McKinley backer Herman Colesat observed that Hannah's behavior around McKinley was, quote, always that of a big, bashful boy toward the girl he loved, end quote.

Speaker 3 McKinley was certainly not taking orders from Hannah or anyone else.

Speaker 3 However, the way that McKinley delegated certain aspects of his political life to Hannah and others meant that the major was often kept in the dark when it came to the less savory parts of 19th-century politics.

Speaker 3 During the McKinley debt crisis, Colesat made a comment that, quote, if McKinley is to stay in politics, he must show clean hands, end quote.

Speaker 3 This comment was allegedly made when McKinley was out of the room and was meant to underscore the point that the job of the men around him was to insulate their political star from any charges of wrongdoing.

Speaker 3 And truly, when you read a biography of William McKinley, you can't help but notice that while there are all sorts of dirty allegations swirling around his presidential campaign and later administration, the man himself always showed clean hands.

Speaker 3 See, if you were to focus exclusively on McKinley himself during the 1896 presidential campaign, his success would seem almost inexplicable.

Speaker 3 His opponent, William Jennings Bryan, went on a truly exhausting tour of the country.

Speaker 3 This barnstorming speaking tour saw the Nebraska-born Democrat deliver an astounding 570 speeches between August and November of 1896. He spoke an average 80,000 words a day.

Speaker 3 On his most ambitious day in Michigan, he delivered 23 speeches. The exertion nearly killed the man and seriously affected his health.

Speaker 3 But there was no denying that he was getting his message to the people and drawing huge crowds in the process.

Speaker 3 McKinley, on the other hand, refused to leave Canton, Ohio. At one point, a worried Mark Hanna urged McKinley that, quote, you've got to stomp or we'll be defeated, end quote.

Speaker 3 But McKinley flatly refused, citing both his wife's delicate health and the now old-fashioned tradition of presidential candidates staying above the fray during the campaigns, and instead letting surrogates go out and speak for them.

Speaker 3 McKinley also recognized that he simply was not the same caliber of speaker as Brian, and famously quipped, quote, I might as well put up a trapeze on my front lawn and compete with some professional athlete as to go out speaking against Brian, end quote.

Speaker 3 This comment would prove to be oddly prophetic, as McKinley would end up creating a kind of political carnival on his front lawn.

Speaker 3 Instead of going out on the stump, McKinley embraced a technique known as the front porch campaign.

Speaker 3 If people wanted to meet with the nominee, then they were invited to come visit him at his home in Canton, Ohio, where he would receive delegations from various civic organizations and make short speeches to the gathered crowd.

Speaker 3 Now, this was not the first of these so-called front porch campaigns in American political history. Presidents Benjamin Harrison and Grover Cleveland had also orchestrated similar things.

Speaker 3 But it would go down as one of the more memorable front porch campaigns.

Speaker 3 As the campaign gathered momentum, McKinley's front lawn became a veritable parade ground, as these carefully vetted delegations of visitors were often accompanied by brass bands, spinnerets, or acrobatic cycling demonstrations.

Speaker 3 The McKinley campaign also provided food and concessions, including free beer, for people who had traveled to Canton.

Speaker 3 It's been estimated that around 750,000 people made their way to Canton, Ohio during the 1896 campaign.

Speaker 3 But again, taken in a vacuum, the enthusiasm for the front porch campaign seems a little hard to understand.

Speaker 3 When compared to William Jennings Bryan, McKinley was barely speaking, and when he was making speeches, he wanted to focus on the somewhat stale issue of protective tariffs.

Speaker 3 The electorate was obviously fired up over the gold versus silver debate, and McKinley didn't really want to talk about it. So, what was going on here?

Speaker 3 Well, while McKinley stayed comfortably in Ohio, Mark Hanna was busy running two separate McKinley campaign headquarters in Chicago and New York City.

Speaker 3 You see, while William McKinley himself was slow to embrace the currency issue, his advisors had identified it as the key to winning the election.

Speaker 3 First, the gold issue was a huge motivator for wealthy industrialists who were legitimately spooked by Bryan's sudden rise in the Democratic Party and early lead in the national polls.

Speaker 3 However, at first, this fear did not necessarily translate into support for McKinley. In the early days of the campaign, contributions from these wealthy men were slow in coming.

Speaker 3 Longtime Republican John Hay commented that, quote, Brian has succeeded in scaring the gold bugs out of their five wits. If he had scared them a little, they would have come down handsomely to Hannah.

Speaker 3 But he has scared them so blue that they think they had better keep what they have got left in their pockets for the evil day. ⁇

Speaker 3 The other key thing was that McKinley had been cagey on where he stood on the question of gold or silver.

Speaker 3 The turning point came when James Hill, a Minnesota railroad tycoon, decided to get involved. Hill had been a lifelong Democrat, but he had been rattled by the rise of William Jennings Bryan.

Speaker 3 Not only was Hill, like most wealthy railroad men, a believer in the gold standard, he was more concerned by Bryan's appeals to a working class consciousness.

Speaker 3 Beyond his worries about the inflationary effects of silver, Hill did not appreciate his class, the owner class, being castigated as greedy exploiters, crucifying the common man on a cross of gold.

Speaker 3 It was Hill who reached out directly to Hanna and pledged his services to the McKinley campaign. What exactly would Hill be doing?

Speaker 3 Well, he would be getting the richest men in America and their corporations to make the biggest contributions to an American political campaign to that point in the nation's history.

Speaker 3 In August of 1896, Hill and Mark Hanna made a tour of Manhattan, stopping at the homes and business offices of many of America's most powerful businessmen and corporations.

Speaker 3 According to historian Scott Miller, their pitch to these titans of industry was less about McKinley and more about stopping the silver movement.

Speaker 3 William McKinley was clearly not enthusiastic about making his campaign all about the gold standard.

Speaker 3 But Hannah and Hill presented McKinley in the New York boardrooms as an unambiguous gold man who would protect the interests of America's corporations.

Speaker 3 Historian Scott Miller points out that, quote, even more pivotal was Hill's reputation as a devout Democrat.

Speaker 3

When he and Hannah appeared in corporate boardrooms, they represented more than the pleadings of the Republican Party. It was a bipartisan effort to fight the silver movement.

End quote.

Speaker 3 Once the big players like J.D. Rockefeller, J.P.

Speaker 3 Morgan, and Cornelius Bliss were on board, much of the rest of the American business community followed suit, often at the urging of these powerful men.

Speaker 3 It was reported that Cornelius Bliss went door to door in lower Manhattan calling on wealthy friends to support the Republican cause. cause.

Speaker 3

J.D. Rockefeller's Standard Oil contributed $250,000 to the campaign, with Rockefeller himself pitching in $2,500.

Banker J.P. Morgan contributed another $250,000.

Speaker 3 A group of railroads brought in $174,000.

Speaker 3 Once again, the Chicago meat packing interests showed up for McKinley, contributing $40,000.

Speaker 3 Many banks and trusts signed agreements with Mark Hanna, whereby they would contribute one quarter of 1% of their overall capital.

Speaker 3 Historian Scott Miller also points out that after the election, officials from the New York Life Insurance Company and the Equitable Company admitted that they, quote, pledged large portions of their clients' premiums to the Republican cause, end quote.

Speaker 3 In the end, the campaign was able to bring in enough money from the big donors to more than cover the over $3.5 million in campaign expenses, which is around $140 million in today's money.

Speaker 3 It was double the previous Republican campaign budget and around 10 times more than what was spent by the Democrats on the Bryan campaign.

Speaker 3 Now, what was Mark Hanna doing with all this money? Well, he was organizing the largest mass mailing of campaign materials to that point in American history.

Speaker 3 His Chicago office blanketed the United States in pamphlets, posters, and small mailers in support of McKinley.

Speaker 3 Lots of this material wasn't even specifically about William McKinley, so much as it was quote-unquote educational material on the gold standard.

Speaker 3 Now, one thing I find interesting about both the Karl Rove and Robert Mary biographies is that they are both comfortable using the term educational material for what Hannah sent in the mail.

Speaker 3

I would argue that that choice of words is a little too benign. These were campaign materials.

You might even call some of it propaganda.

Speaker 3 Interestingly, this material focused most heavily on the very issue McKinley himself was slow to embrace, the gold standard.

Speaker 3 There were point-by-point breakdowns of how silver coinage would hurt the wages of industrial workers.

Speaker 3 There was one particularly effective mailer that was sent to the more rural swing states that coached the reader on how to win an argument against a silver right.

Speaker 3 Hanna and his printers also made sure to print these materials in languages other than English, specifically to target recently arrived immigrant communities who worked as industrial laborers.

Speaker 3

Materials went out in Polish, Italian, German, Yiddish, Greek, and a handful of other languages. They all reiterated the same idea.

Silver currency will hurt your wages.

Speaker 3 The newspapers then joined in on this chorus. The papers were overwhelmingly owned by gold bug Republicans and gold Democrats, and as such, they broke for McKinley in a big way.

Speaker 3 William Jennings Bryan was cast as a radical inciting quote-unquote class hatred, whereas McKinley was presented as a responsible steward of American values and economic stability.

Speaker 3 In one memorable Harper's Weekly political cartoon, the two men were contrasted by showing what each candidate was doing in the 1860s.

Speaker 3 The major was shown heroically donning his Union Army uniform, whereas the much younger Brian was shown as a baby in a crib. The message was clear: Neither man has changed.

Speaker 3 McKinley still defends his country while Brian whines and cries like a baby.

Speaker 3 This media campaign was the key to William McKinley's success.

Speaker 3 The targeted deployment of campaign materials paired with flattering media coverage from gold standard supporting papers helped McKinley's popularity grow, while he himself stayed in Canton, Ohio, and gave short, carefully prepared speeches.

Speaker 3 It was only after the gold issue proved effective in the campaign materials that William McKinley started speaking about the issue more explicitly in his speeches.

Speaker 3 But even then, it was only done sparingly.

Speaker 3 Meanwhile, other Republican speakers like Theodore Roosevelt and John Hay used their well-publicized and reprinted speeches to caricature William Jennings Bryan as a dangerous left-wing revolutionary.

Speaker 3 They called him an anarchist and compared him to Robespierre and other Jacobins from the French Revolution. They also compared his campaign unflatteringly to the more contemporary Paris Commune.

Speaker 3 Roosevelt specifically claimed that Bryan would, quote, substitute the government of Washington and Lincoln with a red government of lawlessness and dishonesty, as fantastic and vicious as the Paris Commune, end quote.

Speaker 3 John Hayes' speech, A Platform of Anarchy, stoked fears that William Jennings Bryan was going to violently redistribute the wealth of the nation.

Speaker 3 Now, this was a totally unfair exaggeration of Bryan's actual policies.

Speaker 3 But it would not be the last time a reformer running a campaign critical of the wealthiest Americans would be cast as a dangerous extremist.

Speaker 3 As the campaign came into its final weeks, the Democrats Democrats started to complain that the Republicans, or perhaps Republican-friendly industries, were starting to use unscrupulous and downright coercive methods to push McKinley over the top.

Speaker 3 And this is where my sources really diverge.

Speaker 3 After the election, the chair of the Democratic National Committee, Senator James K. Jones, wrote that, quote,

Speaker 3 the result of the election was brought about by every kind of coercion and intimidation on the part of the money power, including threats of lockouts and dismissals and impending starvation, by the employment of by far the largest campaign fund ever used in this country, and by the subordination of a large portion of the American press.

Speaker 3 End quote.

Speaker 3 Now, was this true? Did this election hinge on threats of lockouts, dismissals, and starvation?

Speaker 3 Well, there were accusations from all around the country that businesses were actively cajoling their employees to vote for McKinley, in some cases suggesting that employees would lose their jobs if the Republican was not elected president.

Speaker 3 Now, The books I have read on this topic say wildly different things about this, so this is worth focusing on.

Speaker 3 First, the biographer Robert Mary says nothing about this at all,

Speaker 3 which I found strange, because his biography of McKinley seemed relatively balanced and comprehensive.

Speaker 3 To not even mention that there were accusations of coercion by Republican businesses seems like a huge oversight.

Speaker 3 You might say that the accusations accusations of coercion are conspicuous by their absence.

Speaker 3 Carl Rove, on the other hand, mentions that there were accusations, but pointedly says this: quote: The accusations were groundless until one St.

Speaker 3 Louis department store fired a dozen employees for campaigning on company time in mid-October.

Speaker 3 Democrats threatened a lawsuit, the merchant backed down, and the men were rehired, but the damage was done. End quote.

Speaker 3 So, according to Rove, there was no coercion other than one weird incident in St. Louis.

Speaker 3 He goes on to explain how Mark Hanna pushed back against the charges of coercion and even offered a $500 reward for evidence that anything untoward was going on.

Speaker 3 A reward, Rove points out, that was never claimed.

Speaker 3 In Carl Rove's estimation, quote, the Democrats felt like they were onto something with the coercion issue and believed it would help stoke anger towards big corporations and the wealthy, end quote.

Speaker 3 In Rove's estimation, the charges of coercion were little more than a Democratic tactic.

Speaker 3 But I think this is the moment in Karl Rove's book where he really shows his bias.

Speaker 3 Because there is ample evidence that coercion was indeed going on during the final months of the 1896 election campaign. Historians Scott Miller and Hal Williams both attest to this.

Speaker 3 Williams plainly states that there was, quote, ample evidence confirming the charge, end quote.

Speaker 3 Now, to really get to the bottom of this, I dug into both of those authors' footnotes, which led me to the 1938 history of the Gilded Age called The Politicos by historian Matthew Josephson.

Speaker 3 Now, normally I wouldn't cite a source that old, but Josephson really brings his receipts. He supports all of his descriptions of shifty election tactics with contemporary newspaper reports.

Speaker 3 So, what was actually going down here?

Speaker 3 Well, the earliest reports come from the more rural swing states. The St.

Speaker 3 James Gazette reported that in the months leading up to the 1896 election, agents from insurance companies based in New York and Connecticut went door to door in farming communities, quote, informing their debtors that if McKinley were elected, their mortgages would be extended for five years at a low rate of interest, end quote.

Speaker 3 Railroad companies started stuffing notices into pay envelopes, warning employees that their jobs would be in danger if the companies had to, quote, pay bond interests in gold while earning depreciated American money, end quote.

Speaker 3 Some companies were even less subtle. On September 5th, 1896, the McCormick Machine Company told its employees point blank that the factory would close if William Jennings Bryan won the election.

Speaker 3 The great meat packing houses of Chicago allegedly spread similar rumors. The factories would go down if McKinley did not win.

Speaker 3 In 1896, William Steinway, the head of the famous Steinway Piano Works, was particularly active in the cause to preserve the gold standard.

Speaker 3 He was widely quoted in the papers saying to his employees before the election, quote, men, vote as you please, but if Brian is elected tomorrow, the whistles will not blow Wednesday morning, end quote.

Speaker 3 All over the country, there were also reports of so-called contingent deals being made with manufacturers.

Speaker 3 Basically, large orders were placed and were only to be filled on the contingency that McKinley won the election.

Speaker 3 One of the more blatant examples of this was reported by the Wilmington, Delaware Morning News, who explained that a shipbuilding contract worth $300,000 had been placed with the Harlan and Hollingworths Company, contingent on Brian losing the election.

Speaker 3 If Brian won, the ships would not be built.

Speaker 3 There's no doubt that big business was doing everything they could to get William McKinley elected.

Speaker 3 Now, how much did William McKinley know about this personally?

Speaker 3 It's unclear, and certainly he publicly denied that any type of coercion was going on.

Speaker 3 And to be fair, these dirty tactics were likely not directed by McKinley, his campaign, or even the Republican Party.

Speaker 3 These were business owners taking taking matters into their own hands and trying to put their thumbs on the scales of American democracy. McKinley, as always, showed clean hands.

Speaker 3 Now, to be clear, I don't want it to sound like there were obvious heroes and villains in 1896.

Speaker 3 The Democratic Party had its own baggage.

Speaker 3 It would be irresponsible of me not to point out that the Democratic Party were actively suppressing the votes of thousands upon thousands of black Americans in the South during this election.

Speaker 3 Hypocrisy reigned in 1896.

Speaker 3 But I would argue that if you want to understand how William McKinley got elected, you need to understand the active role that American business took in that endeavor.

Speaker 3 The clincher came in October with a classic October surprise.

Speaker 3 In October of 1896, the wheat harvests failed in Russia, Australia, and India.

Speaker 3 This drove up the price for American wheat. Silver currency was no longer needed to rescue the American farmer.

Speaker 3 The fact that wheat prices had gone up without the introduction of silver currency undermined the silverite argument that only silver currency would bring up the price of wheat.

Speaker 3 A global wheat shortage had demonstrated that that wasn't true. American farmers started earning again, and Bryan's popularity slipped.

Speaker 3 In the end, the vote was still tight. William Jennings Bryan carried the South and most of the American West as predicted.

Speaker 3 But McKinley had the Northeast and, crucially, the Midwest locked up, giving him a majority in the Electoral College. He also won 51% of the popular vote.

Speaker 3 But here's the thing. As I've hopefully shown,

Speaker 3 There are very different ways that you can tell the story of McKinley's 1896 win.

Speaker 3 Carl Rove, and to a lesser extent, Robert Mary, present 1896 as the story of Americans choosing the moral, sensible Republican over a reckless Democrat stirring up class hatred.

Speaker 3 But to do this, they either ignore or explain away the more unsavory parts of McKinley's road to victory.

Speaker 3 In this way, Carl Rove's book is especially biased.

Speaker 3 He smooths out many of the rough edges to present William McKinley as a certain type of Republican ideal that perhaps modern politicians could aspire to be like.

Speaker 3 A good man who could make the case to workers that their interests were the same as the interests of their bosses.

Speaker 3 You see, there's no doubt that McKinley was a principled, empathetic, and decent man. But that does not explain his victory in 1896.

Speaker 3 In fact, it seems like he was insulated from many of the tactics and campaign strategies that made him president.

Speaker 3 To understand 1896, you need to understand how corporate money, printed campaign propaganda, and workplace coercion were used to influence the American electorate.

Speaker 3 In 1896, America's industrialists became political activists in a new and profound way.

Speaker 3 So

Speaker 3 that was how William McKinley became president. But how would he act once he had the job?

Speaker 3 Okay,

Speaker 3

that's all for this week. Join us again in two weeks' time when we will wrap up our look at William McKinley.

Before we go this week, as always, I need to give some shout-outs.

Speaker 3 Big ups to Ben Cohen, to Henry, to Sophia Perez, to Cecilia Sang, to Pete Spearin, to Shafitis, to Robert Hobbit 5, to Brian Vieira, to Danny Smith, to Dylan White, to Demon Fall Down,

Speaker 3 to Martin Robistow, to Kyler Moltzan, to Jonathan McDowell, to Orion Gilliam, to Hillix,

Speaker 3 to Ruby Coffiner, to Proofrock Spoons,

Speaker 3 to Autumn Rigby, to Dagum, to Craig Harris, to Michael Burt,

Speaker 3 to

Speaker 3 Ruru,

Speaker 3 to David Dibble,

Speaker 3 to Sidney Steiner and to P4ninu.

Speaker 3 I don't know what that is. I think you know who you are, P4niu.

Speaker 3 All of you folks have decided to pledge at $5

Speaker 3

or more every month. So you know what that means.

You are beautiful human beings. I cannot say this enough.

The support of the patrons means everything.

Speaker 3 Thank you, thank you, thank you for your continued support.

Speaker 3 I want to give one more reminder that we are going to be doing another QA show after this series has finished up.

Speaker 3 So if you have any questions about William McKinley or anything else, please email them to me at ourfakehistory at gmail.com.

Speaker 3 And patrons, please use the chat I have set up at the Patreon website specifically about the William McKinley series.

Speaker 3

Otherwise, you can reach out to me through Facebook, facebook.com slash our fake history. You can find me on all the socials at Ourfake History.

We're talking Blue Sky. We're talking TikTok.

Speaker 3 We're talking Instagram.

Speaker 3 Look for me at Ourfake History and you shall find me. You can also go to the website, ourfakehistory.com.

Speaker 3 Check out the bibliography and work cited I have there if you're curious about the sources I'm using for this show.

Speaker 3 As always, the theme music for this show comes to us from Dirty Church. Check out more from Dirty Church at dirtychurch.bandcamp.com.

Speaker 3 All the other music you heard on the show today was written and recorded by me. My name is Sebastian Major, and remember, just because it didn't happen doesn't mean it isn't real.

Speaker 3 One, two, three, five.

Speaker 3 This summer, Pluto TV is exploding with thousands of free movies. Summer of Cinema is here.

Speaker 3 Feel the explosive action all summer long with movies like Gladiator, Mission Impossible, Beverly Hills Cop, Good Burger, and Transformers Dark of the Moon.

Speaker 3

Bring the action with you and stream for free from all your favorite devices. Pluto TV.

Stream now, pay never.

Speaker 4 Hey, it's James Albicher. I've been an entrepreneur, investor, best-selling writer, stand-up comic, and whatever it is I'm interested in, I get obsessed.

Speaker 4

Yes, it's led to success, but it's also led to such heartbreaking failure. I have failed more times than I can count.

I wish in my life I had had people to talk to.

Speaker 4 That's why I started the James Altersher show and bring on some of the most brilliant minds in every area of life.

Speaker 4 People like Richard Branson, Sarah Blakely, Mark Cuban, Danica Patrick, Gary Kasproth. And I wanted to find out exactly how they've navigated the highs, the lows, and everything in between.

Speaker 4 No fluff, just raw stories and real advice. I've talked to 1,500 of the most amazing people on the planet.

Speaker 4 So if you want to learn from the best and skip the same old canned interviews, we're all about helping you find your next big idea, level up your thinking, and ultimately to choose yourself.

Speaker 4 So let's do this together. Subscribe now to the James Altiter Show.

Speaker 5 What if Juliet got a second chance at life after Romeo?

Speaker 5 And Juliet, the new hit Broadway musical and the most fun you'll have in a theater. I got the I Don't,

Speaker 5 created by the Emmy-winning writer from Schiff's Creek and pop music's number one hitmaker. And Juliet is exactly what we need right now.

Speaker 5 Playing October 7th through 12th at the San Jose Center for the Performing Arts. Tickets now on sale at BroadwaySanjose.com.