Episode #230 - Why President McKinley? (Part I)

The 25th President of the United States, William McKinley, has recently been in the news. In the 2025 inaugural address it was announced that Alaska's highest peak would once again be known as Mt. McKinley to honour the former President, who was apparently a "great businessman" who made America "very rich." Like many, Sebastian found this newfound interest in president McKinley rather curious. For most of the 20th century he was overshadowed by his successor Theodore Roosevelt, who once claimed that McKinley had the "backbone of a chocolate éclair." Why had this particular President been plucked from history and held up as worthy of emulation? It turns out a growing number of American conservatives, including Republican strategist Karl Rove, have been attempting to revive McKinley's reputation for years. What do they see in this turn-of-the-century politician? Tune-in and find out how threats to annex Canada, civil war stories, and boom-bust capitalism all play a role in the story.

Our Fake History listeners can grab Rosetta Stone’s LIFETIME Membership for 50% OFF! That’s unlimited access to 25 language courses, for life! Visit Rosettastone.com/HISTORY to get started and claim your 50% off TODAY!

New members can try Audible now free for 30 days and dive into a world of new thrills. Visit Audible.com/OFH or text OFH to 500-500 that’s Audible.com/OFH or text OFH to 500-500.

Check out progressive.com

See Privacy Policy at https://art19.com/privacy and California Privacy Notice at https://art19.com/privacy#do-not-sell-my-info.

Press play and read along

Transcript

Speaker 1 You're juggling a lot, full-time job, side hustle, maybe a family, and now you're thinking about grad school? That's not crazy. That's ambitious.

Speaker 1 At American Public University, we respect the hustle and we're built for it. Our flexible online master's programs are made for real life because big dreams deserve a real path.

Speaker 1 At APU, the bigger your ambition, the better we fit. Learn more about our 40-plus career-relevant master's degrees and certificates at apu.apus.edu.

Speaker 1 A happy place comes in many colors.

Speaker 2

Whatever your color, bring happiness home with Certipro Painters. Get started today at Certipro.com.

Each Certipro Painters business is independently owned and operated.

Speaker 2 Contractor license and registration information is available at certipro.com.

Speaker 3 Audival's romance collection has something to satisfy every side of you. When it comes to what kind of romance you're into, you don't have to choose just one.

Speaker 3 Fancy a dalliance with a duke or maybe a steamy billionaire. You could find a book boyfriend in the city and another one tearing tearing it up on the hockey field.

Speaker 3 And if nothing on this earth satisfies, you can always find love in another realm. Discover modern rom-coms from authors like Lily Chu and Allie Hazelwood, the latest romanticy series from Sarah J.

Speaker 3 Mas and Rebecca Yaros, plus regency favorites like Bridgerton and Outlander. And of course, all the really steamy stuff.

Speaker 3 Your first great love story is free when you sign up for a free 30-day trial at audible.com slash wondery. That's audible.com/slash wondery.

Speaker 4 Friends, if you've been listening to this show for any length of time, then you know that our fake history has never explicitly been about contemporary politics.

Speaker 4 Oh, sure, when I'm feeling a little puffed up, I like to think that one might be able to glean some insights from this show that might shed some light on our current moment.

Speaker 4 But this is not a current events show.

Speaker 4 In fact, I know many of you listening are immediately put off by anything that might resemble a political opinion.

Speaker 4 I'm deeply aware that mentioning anything about our current political moment is a minefield. So perhaps it's best to just avoid it.

Speaker 4 But

Speaker 4 sometimes things bubble up in the discourse that are hard for me to ignore.

Speaker 4 As fans of this podcast know, one of my enduring interests is how history is reframed, reimagined, and then redeployed to suit a particular occasion.

Speaker 4 Anytime a politician or public figure decides that they're going to draw parallels to a particular historical moment, or perhaps valorize or condemn a particular historical figure, my ears always perk up.

Speaker 4 A master's degree in public history and 10 years making this podcast has trained me to look carefully at how history is used and abused in the public discourse.

Speaker 4 I'm fascinated by why certain events or figures gain attention at specific moments. What rhetorical function are they serving?

Speaker 4 And most importantly, for me anyway, are these events or figures being presented in a reasonably honest and well-researched way?

Speaker 4 In other words, are the speakers referencing history or are they reinforcing historical myths?

Speaker 4 This is one of my great concerns.

Speaker 4 I get especially interested when a public figure decides that they are going to focus in on a lesser known piece of history or a more obscure figure from the past.

Speaker 4 So often speakers go to the same well for their historical references to the point where those references become hackneyed clichés.

Speaker 4 Take for example the American presidents.

Speaker 4

There are certain presidents who get a lot of focus in modern rhetoric. The founding fathers are cited ad nauseum.

George Washington and Thomas Jefferson are quoted as a matter of course.

Speaker 4 Abraham Lincoln is a perennial favorite, to the point where most people can reel off the first few lines of the Gettysburg Address.

Speaker 4 FDR and his New Deal are referenced constantly. The heady early days of the JFK administration also provide good fodder for contemporary speech writers.

Speaker 4 So,

Speaker 4

I'm always interested when a speaker changes things up. As a history nerd, I appreciate the the variety.

After all, the human experience is as broad as our history is deep.

Speaker 4 There is so much one could choose from. Why focus on the same handful of historical references?

Speaker 4 But then, sometimes a historical reference will surprise me. I found myself surprised recently by someone I didn't think could surprise me anymore, the current President of the United States.

Speaker 4 On the 2024 campaign trail, Donald Trump started peppering his stump speeches with references to a U.S. president that he described as, quote, great

Speaker 4 but highly underrated, end quote.

Speaker 4 That president was the 25th person to ever hold the office, the relatively obscure William McKinley.

Speaker 4 Now, I don't know about you folks, but I found Trump's newfound interest in this often overlooked turn-of-the-century commander-in-chief to be a little curious.

Speaker 4 What was it about that particular American president that had caught the attention of Donald Trump?

Speaker 4 It's especially surprising because during Trump's first term, he loudly proclaimed his admiration for a very different American president, Andrew Jackson.

Speaker 4 The Appalachian Democrat, had a reputation as a fiery populist who cast himself as a political outsider willing to break the rules to get results.

Speaker 4 That way, it didn't seem strange that Donald Trump pointed to Andrew Jackson as a president worthy of admiration.

Speaker 4 But McKinley, hmm, I mean, William McKinley was a very different beast.

Speaker 4 Biographer Robert Mary has described the Ohio-born 25th president as quote, affable, stolid, and seemingly plotting, possessing a self-effacing solicitude rare in most high-powered men, end quote.

Speaker 4 Further, the president was quote, cautious, methodical, and a master of incrementalism.

Speaker 4 Finally, this quote, kindly and sweet-tempered politician rarely twisted arms in efforts at political persuasion, never raised his voice in political cajolery, and didn't visibly seek revenge. ⁇

Speaker 4 In other words, William McKinley was no Andrew Jackson.

Speaker 4 So why McKinley?

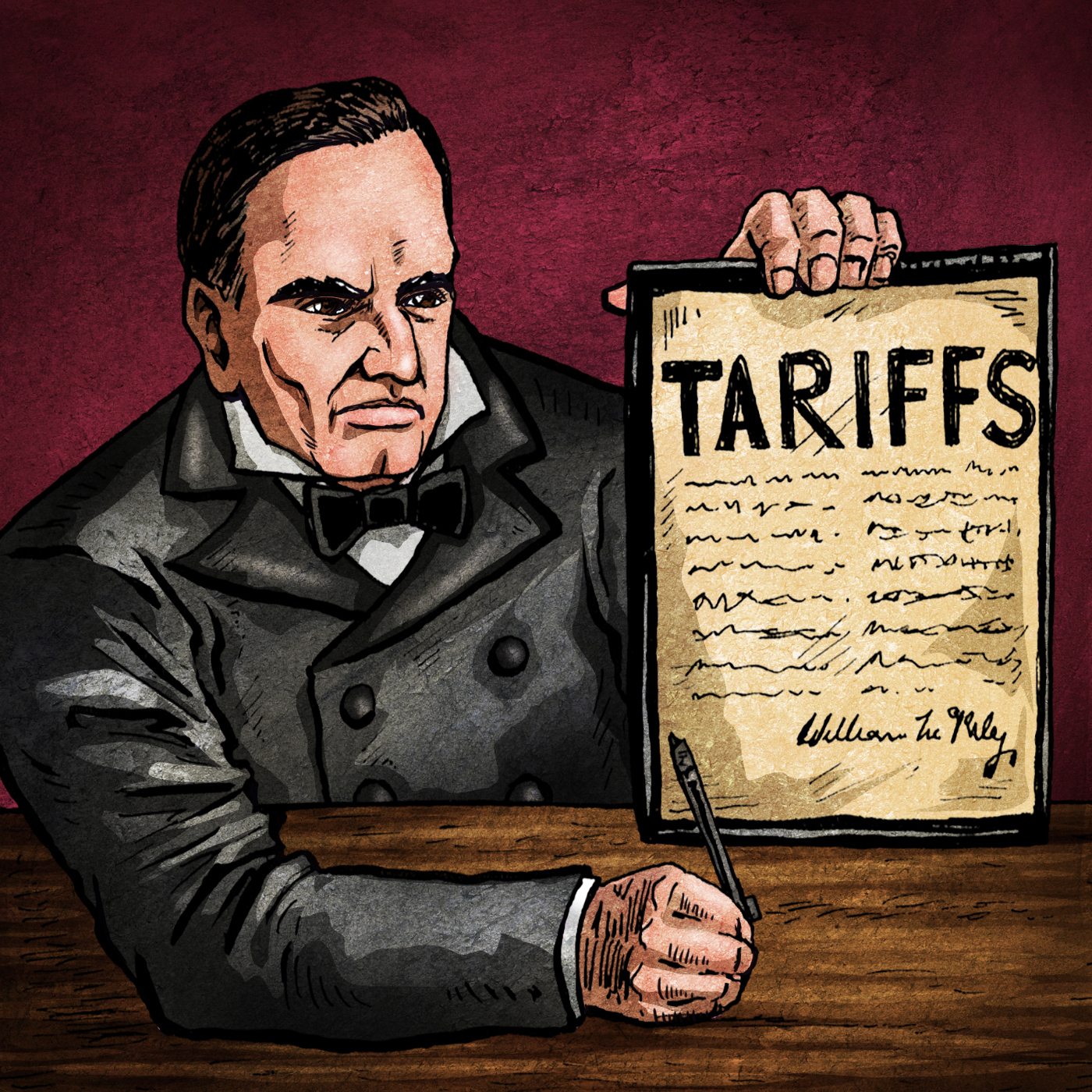

Speaker 4 Well, on the face of it, the answer is fairly simple. tariffs.

Speaker 4 In his time as a congressman before running for president, William McKinley had been one of America's most vocal advocates for protective tariffs.

Speaker 4 Given that the 47th president has made tariffs such an essential part of his agenda, it's perhaps not surprising that he has gravitated towards a 19th century politician who once proudly proclaimed, quote, I am a tariff man standing on a tariff platform, end quote.

Speaker 4 It seems to be this very specific aspect of McKinley's legacy that has piqued the attention of the current president.

Speaker 4 Very rarely does Trump mention McKinley without making note of his position on tariffs.

Speaker 4 Take, for example, the 2025 inaugural address, where the president proclaimed that, quote, we will restore the name of a great president, William McKinley, to Mount McKinley, where it should be and where it belongs.

Speaker 4

President McKinley made our country very rich through tariffs and through talent. He was a natural businessman.

End quote.

Speaker 4 Renaming Alaska's highest peak Mount McKinley is a remarkable choice in 2025.

Speaker 4 But I'm sure many of you who heard that inaugural address were left wondering, who was President McKinley? What did he achieve as President of the United States?

Speaker 4 And why was he being so enthusiastically embraced by the current president?

Speaker 4 Was it true that his tariff policy had made America very rich?

Speaker 4 Well, the truth, as always, is complicated.

Speaker 4 What fascinates me is how William McKinley's historical reputation has gone through a number of re-evaluations in the century plus since his assassination in 1901.

Speaker 4 His shocking murder at the outset of his second term meant that McKinley's time in office was cut short.

Speaker 4 From there, he was largely overshadowed by his showy and highly quotable successor, Theodore Roosevelt.

Speaker 4 The story of American politics at the turn of the century is often told through the lens of Roosevelt's career.

Speaker 4 Even McKinley's most significant foreign policy achievement, the victory in the Spanish-American War, is often presented as one of Theodore Roosevelt's adventures, thanks to his choice to serve in battle with his flamboyant volunteer cavalry division known as the Rough Riders.

Speaker 4 Roosevelt would quite literally have his position as a significant president engraved in stone when his bespectacled face face was blasted onto the side of Mount Rushmore.

Speaker 4 McKinley was simply not managing his legacy in the same ostentatious way.

Speaker 4 It didn't help that Roosevelt was not always kind to McKinley's presidential record. He once acidly remarked that his predecessor had, quote, all the backbone of a chocolate eclair, end quote.

Speaker 4 It seems that for many generations, Roosevelt's withering criticism of McKinley as an ineffectual, weak-willed president who, quote, lacked the cold instinct for audacious and functional leadership, end quote, held sway among historians.

Speaker 4 According to the historian John L. Offner, quote, for much of the 20th century, McKinley was portrayed as a man of limited ability.

Speaker 4 Historians, biographers, and political commentators cast doubt on his capacities, describing him as weak, indecisive, feckless, and so forth.

Speaker 4 Roosevelt's Eclair quotation would then cap the argument, providing a useful and colorful summary.

Speaker 4 So, given the many decades of fairly dismissive takes on McKinley's presidency by popular historians, his recent reclamation as a great and underrated president is all the more remarkable.

Speaker 4 But as I have learned, this resurrection of William McKinley's historical reputation is not something that happened overnight.

Speaker 4 Starting in the 1980s, historians started giving more nuanced takes on the strengths and weaknesses of McKinley's leadership style.

Speaker 4 But then, more recently, there have been a small run of considerably more celebratory biographies of William McKinley.

Speaker 4 Robert Mary's 2017 biography, President McKinley, used its subtitle to proclaim McKinley the, quote, architect of the American century, end quote.

Speaker 4 This far more laudatory tone was in keeping with the 2015 book on McKinley's 1896 presidential campaign titled, The Triumph of William McKinley.

Speaker 4 Clearly, McKinley's historical star has been on the rise. But what struck me was who was writing these books.

Speaker 4 Robert Mary served as the editor of the bi-monthly magazine, The American Conservative, from 2016 to 2018, and as such has a bit of a profile as well, a prominent American conservative.

Speaker 4 The author of The Triumph of William McKinley is none other than Carl Rove,

Speaker 4 the Republican political operative who served as senior advisor and deputy chief of staff during the George W. Bush administration.

Speaker 4 Bush himself called Carl Rove the, quote, architect of his two successful presidential campaigns.

Speaker 4 I think it's noteworthy that two well-known American conservatives, including one of the most controversial Republican strategists of the past 25 years,

Speaker 4 have not only taken an interest in William McKinley, but have written largely celebratory biographies of the 25th president.

Speaker 4 But still, I find this curious because once again, McKinley is not an obvious choice. The politics of the late 19th century do not easily map onto the politics of the 21st century.

Speaker 4 So, why the interest in McKinley?

Speaker 4 Clearly, there's a growing group of historians and politicians on the American political right who see something significant in the somewhat forgotten presidency of William McKinley.

Speaker 4 But what exactly is it?

Speaker 4 Surely, this goes beyond tariffs.

Speaker 4 Let's see if we can piece it together today on our fake history.

Speaker 4 One, two, three, five

Speaker 4 Episode number 230, Why President McKinley? Part 1.

Speaker 4 Hello, and welcome to Our Fake History.

Speaker 4 My name is Sebastian Major, and this is the podcast where we explore historical myths and try to determine what's fact, what's fiction, and what is such a good story, it simply must be told.

Speaker 4 Before we get going this week, I just want to remind everyone listening that an ad-free version of this podcast is available through Patreon.

Speaker 4 Just head over to patreon.com slash ourfakehistory and start supporting at $5 or more every month to get access to an ad-free feed and a long list of our fake history extra episodes, including our most recent epic two-hour patrons only extra episode on the Bronze Age Collapse.

Speaker 4 The patrons really seem to be enjoying that episode.

Speaker 4 So, if you want to hear that and also get access to our super fun Patreon community and the chat groups where people can ask me questions that get featured on our bonus episodes, then please go to patreon.com/slash our fake history, find the level of support that works for you, and get access to a long list of cool extras.

Speaker 4 This week, we are heading to the late 19th century to explore the presidency and historical legacy of America's 25th president, William McKinley.

Speaker 4 Now, I have been considering doing this topic for a few months now, but I've been hesitant.

Speaker 4 As I mentioned at the outset, I've generally tried to keep contemporary politics at an arm's length from this show.

Speaker 4 That's not to say that this show has not dabbled in the political or even that my own political perspectives have not seeped in from time time to time.

Speaker 4 But I know that many listeners get turned off if a history shows gets especially preachy or comes off as unreasonably partisan.

Speaker 4 It's something that I've tried to remain sensitive to over the past 10 years in an attempt to keep this show as big a tent as it can be, so to speak.

Speaker 4 I've always approached hosting this podcast the same way I approached teaching.

Speaker 4 As a high school history and social science teacher, my job was to expose my students to new ideas, challenge them to think critically, encourage empathy, and give them the tools to analyze texts, art, the media, and historical sources.

Speaker 4 My job was not to convince them that I was right about stuff. You know what I mean?

Speaker 4 I've tried to bring the same approach to this podcast, while also having fun with these amazing stories from our past.

Speaker 4 One of my favorite teachers used to start his class with a quote from the great philosopher Hannah Arendt, who once said that, quote, education is the point in which we decide if we love the world enough to assume responsibility for it, end quote.

Speaker 4 That always stuck with me. The point of any educational endeavor should be about trying

Speaker 4 show what there is to love about the world, while also being clear-eyed about the challenges that the world faces.

Speaker 4 Now, that mission can sometimes get derailed when one gets bogged down in the nitty-gritty of whatever our current political moment is.

Speaker 4 I'm quite aware that many of you listen to this podcast as a bit of an escape from the endless noise of political news. And I certainly do not want to contribute to that noise.

Speaker 4 So it was with great trepidation that I wrote an introduction where I quoted the inauguration speech of the current American president.

Speaker 4 But I did it because I really want to talk about William McKinley. And William McKinley has become weirdly relevant again thanks to Donald Trump.

Speaker 4 But despite the fact that McKinley's name has been in the news more in the last six months than it has in the last 80 years, his life and presidency remain poorly understood.

Speaker 4 The more I dug into the history of President McKinley, the more I came to realize that he was a perfect figure for the Our Fake History treatment.

Speaker 4 While there might not be any well-known McKinley myths, he is a president with a contested legacy and a deeply complicated historical reputation.

Speaker 4 He's been both written off as a cowardly jellyfish and condemned as a violent imperialist.

Speaker 4 He's been saluted as a forward-looking progressive with deep humanitarian convictions and scoffed at as the pleasant-faced puppet of exploitative American industrialists, warmongers, and greedy bankers.

Speaker 4 It's even been suggested that L. Frankbaum's Wizard of Oz may have been a veiled satire of President McKinley, a cowardly flim-flam artist being controlled by shadowy men behind the curtain.

Speaker 4 The fact that McKinley has such a messy, awkward, and complex historical reputation has made his recent re-emergence as a great businessman who made America very rich all the more interesting to me.

Speaker 4 I couldn't help but wonder: was this recent fascination with McKinley just about tariffs? Or was there something more to this?

Speaker 4 Then I learned that one of the most recent biographies of William McKinley was written by Carl Rove.

Speaker 4 And I was like,

Speaker 4 okay,

Speaker 4 something's going on here.

Speaker 4 If one of the best-known Republican political strategists of the last 25 years felt the need to write a 379-page book about McKinley, what does that tell us about McKinley's evolving historical reputation?

Speaker 4 To be honest, I wasn't quite sure at first.

Speaker 4 The thing that all McKinley biographers have to reckon with is what the American diplomat and historian Warren Zimmerman called the, quote, tantalizing enigma of William McKinley.

Speaker 4 McKinley was not an ideologue, nor do his politics neatly align with those of the modern Republican or Democratic parties.

Speaker 4 So what's the appeal here?

Speaker 4 Well, the more I've dug into McKinley's political career and time as president, the more I've come to understand what makes him a significant historical figure, and also what makes him attractive to these modern biographers.

Speaker 4 I think getting a deeper understanding of McKinley can hopefully give us a more nuanced understanding of our own strange moment in history. So

Speaker 4 let's get into it.

Speaker 4 Today's episode of Our Fake History is being brought to you by Rosetta Stone.

Speaker 4 Whether you're traveling abroad, planning a staycation, or just shaking up your routine, what better time to dive into a new language?

Speaker 4 With Rosetta Stone, you can turn downtime into meaningful progress.

Speaker 4 One feature of Rosetta Stone that I think is really cool is something called True Accent, which helps you learn a language in the accent that people who speak it actually use.

Speaker 4

You can learn anytime, anywhere. Rosetta Stone fits your lifestyle with flexible on-the-go learning.

You can access lessons from your desktop or mobile app, whether you have five minutes or an hour.

Speaker 4

It's an incredible value too. Learn for life.

A lifetime membership gives you access to all 25 languages, so you can learn as many as you want whenever you want. Don't wait.

Speaker 4

Unlock your language learning potential now. Our fake history listeners can grab Rosetta Stone's lifetime membership for 50% off.

That's unlimited access to 25 language courses for life.

Speaker 4

Visit RosettaStone.com slash history to get started and claim your 50% off today. Don't miss out.

Go to rosettastone.com slash history and start learning today.

Speaker 4

Today's episode of Our Fake History is being brought to you by Progressive Insurance. You chose to hit play on this podcast today.

Smart Choice. Progressive loves to help people make smart choices.

Speaker 4 That's why they offer a tool called Auto Quote Explorer that allows you to compare your progressive car insurance quote with rates from other companies.

Speaker 4 So you save time on the research and can enjoy savings when you choose the best rate for you. Give it a try after this episode at progressive.com.

Speaker 4

Progressive casualty insurance company and affiliates. Not available in all states or situations.

Prices vary based on how you buy.

Speaker 4 William McKinley was born in Niles, Ohio in 1843. His father, William McKinley Sr., was an ironmonger, as his father had been before him.

Speaker 4 In fact, the McKinleys were one of the first significant iron manufacturers in Ohio. They were among some of the first people to make the rust belt rusty.

Speaker 4 William Sr. would eventually operate four iron foundries around the state.

Speaker 4 The family were all pious Methodists. William Jr.'s mother, Allison, had vocally encouraged her academically successful son to seek a career in the ministry.

Speaker 4 Now, this was obviously not in the cards for William Jr.,

Speaker 4 but he would remain a committed Methodist his entire life.

Speaker 4 This religious conviction also affected the family's politics, which were staunchly abolitionist.

Speaker 4 The McKinleys were deeply opposed to the institution of slavery. The family subscribed to abolitionist publications and even left collections of abolition-minded poetry in the family parlor.

Speaker 4 The McKinleys were part of a growing group of Americans that were deeply committed to ending what they saw as an evil and inhuman institution.

Speaker 4 It probably comes as no surprise then that when the Civil War broke out in 1861, William McKinley, only 18 years old at the time, enlisted in the Union Army.

Speaker 4 To his credit, the young man distinguished himself during his service. He quickly shot through the ranks, and by the age of 22, he had made the rank of brevet major.

Speaker 4 In fact, for the rest of his life, he preferred the title major to any other that he would come to possess.

Speaker 4 He was known to modestly quip of that title, quote, I earned that one, I'm not so sure about the others, end quote.

Speaker 4 And by the way, no biographer misses that particular quote, as it seems very illustrative of McKinley's character. He was humble and had a very distinctive, self-effacing sense of humor.

Speaker 4 But I would also add that he was calculating and politically astute.

Speaker 4 Sure, he was joking that maybe he didn't really earn any of his political titles, but he was also reminding you that he was a serviceman who had proudly risked his life for the Union.

Speaker 4 This was part of McKinley's style as a politician. It's what we in the 21st century call a humble brag.

Speaker 4 Now, one of the most often told stories about McKinley during the war took place during the Battle of Antietam, the bloodiest single day in American combat history.

Speaker 4 The story goes that at the time, McKinley was a commissary sergeant, that is, a non-commissioned officer in charge of distributing food and other supplies.

Speaker 4 On the morning of the battle, a brigade, including a company of fellow Ohioans, managed to capture a strategic bridge across Antietam Creek, but almost immediately they were pinned down by Confederate gunfire and cut off from the larger body of the Union forces.

Speaker 4 What's worse, this early morning strike on the bridge had meant that the men had not eaten anything all day.

Speaker 4 They were now famished and very thirsty.

Speaker 4 Hearing about this, Commissary Sergeant McKinley loaded a horse-drawn carriage full of food and drink and set off to personally resupply the pinned-down brigade.

Speaker 4 Along the way, McKinley was ordered back by two separate Union commanders who told him that the path to the brigade's position was too well covered by enemy fire to be safely traversed.

Speaker 4 He talked his way past one of these commanders and flatly ignored the other.

Speaker 4 Then, urging his horses to a full gallop, McKinley made the run across the line of fire.

Speaker 4 Apparently, a cannonball even managed to connect with the back of his wagon, but a few minutes later, he arrived, quote, safe in the midst of the half-famished regiment, end quote.

Speaker 4 The supplies were largely intact despite the cannonball, and the relieved men toasted McKinley as the hero of the day.

Speaker 4 Now, it's a great little story, and all the biographers agree that it's true. But it's also the kind of story that served him well in his political career.

Speaker 4 This one was told and retold by McKinley and his supporters.

Speaker 4 It's nice when your war story is about an act of bravery that led to you feeding your imperiled comrades, as opposed to a story where the president killed Americans, even if they were Confederate soldiers.

Speaker 4 It's not that McKinley's favorite war story wasn't true. It's just notable that this particular tale was emphasized.

Speaker 4 Still, it's clear that McKinley's time as a soldier and particularly his experience at the Battle of Antietam stayed with him.

Speaker 4 The thousands of dead soldiers he witnessed pulled from the battlefield that day gave him a profound respect for the human cost of war.

Speaker 4 It would be wrong to call William McKinley a pacifist, but he had no great appetite for war. He understood its cost.

Speaker 4 This earned distaste for armed conflict would eventually become one of the great ironies of McKinley's presidency. But we'll get to that.

Speaker 4 While McKinley was in the Union Army, he developed a relationship with his commanding officer, one Rutherford B. Hayes, a man who would go on to be the 19th president of the United States.

Speaker 4 Hayes was an early mentor to McKinley, and his political ambitions no doubt influenced the young McKinley on his own path. If you personally know someone who becomes the president,

Speaker 4 you might feel like you could do it too.

Speaker 4 Everything about William McKinley's biography up to the end of the American Civil War pushed him towards the Republican Party.

Speaker 4 And this gives me an opportunity to speak about the ideological composition of the two major political parties of this period.

Speaker 4 First,

Speaker 4 we need to recognize that the Democratic and Republican parties of the late 19th century were both dramatically different institutions than what they have become in the 21st century.

Speaker 4 In fact, I would argue that both parties were so different from their current iterations that it can be a little disorienting that they're still called the Republican and the Democratic parties.

Speaker 4 One of my pet peeves in our current political climate is when someone tries to dunk on either the Democrats or the Republicans based on something those parties did in the 19th century.

Speaker 4 That is ridiculous because it ignores just how many times those parties have been transformed and realigned in the intervening 100 plus years.

Speaker 4 The other thing that can be a little disorienting is that the two major American political parties of this period do not easily map onto our contemporary understanding of the political spectrum.

Speaker 4 It's hard to characterize either 19th century party using the terms left-wing or right-wing.

Speaker 4 Allow me to explain.

Speaker 4 When William McKinley became a Republican, it was still very much the party of Abraham Lincoln.

Speaker 4 The Republicans were the party of abolitionism, the Emancipation Proclamation, the 13th Amendment, and then Reconstruction.

Speaker 4 The post-Civil War Republicans were considered progressives when it came to the question of race and enfranchisement in America.

Speaker 4 They believed in a strong federal government that would lead the charge on those fronts.

Speaker 4 Indeed, one of William McKinley's lifelong political priorities was the protection of voting rights for black Americans.

Speaker 4 McKinley even once gave a speech early in his political career, making the case for women's suffrage when that movement was still in its infancy.

Speaker 4 The rift of the American Civil War made the Republicans the party of the North, and more specifically, the Northeast.

Speaker 4 This meant that on top of their progressive racial policies, they also represented the priorities of America's industrial and financial hubs.

Speaker 4 As such, they had a lot of support from America's bankers, financiers, and industrialists in the country's Northeast.

Speaker 4 In many ways, they were the party of American capital and were quite friendly to American big business. Now, hopefully, you can see how McKinley slotted in perfectly to all of this.

Speaker 4 He was a lifelong abolitionist, a progressive Methodist, and the son of a man who owned iron foundries.

Speaker 4 In this way, he combined both 19th-century Republican humanitarian politics with a deep connection to America's industrial owner class.

Speaker 4 The 19th century Democrats, on the other hand, were the party of the South. A faction of the Democrats in the Union had advocated peace with the Confederacy and supported the continuation of slavery.

Speaker 4 Democrats largely stood in the way of Southern Reconstruction, and Southern Democrats led the charge in the creation of the so-called Jim Crow segregation laws.

Speaker 4 But nationally, they became the party opposed to the consolidation of political and economic power in the hands of the industrial elite.

Speaker 4 In the years after the Civil War, the Democrats became the party of the small farmer, the tradesperson, and the artisan.

Speaker 4 This focus on farms helped expand their base beyond the so-called solid South and into the largely agrarian American West.

Speaker 4 As such, the Democrats supported policies that were designed to help America's small farmers, even when they conflicted with the priorities of American big business or the banks.

Speaker 4 Generally, the Democrats were the party of small government and states' rights in this period, which went hand in hand with their support of segregation.

Speaker 4 As America started rapidly industrializing, the Democrats started courting labor movements and pushed against the consolidation of wealth into the hands of an increasingly small number of millionaires, lampooned as the robber barons.

Speaker 4 They also started supporting government intervention in the economy. so long as it benefited their rural constituency.

Speaker 4 But what's difficult for someone like me trying to create a thumbnail sketch of both of these parties is that by McKinley's era, both major political parties were in a state of flux.

Speaker 4 As much as the Democrats presented themselves as the party of the rural little guy, there are many examples of Democrats courting American big business.

Speaker 4 By the same token, there were Republican progressives who courted labor movements and pushed against capitalist excess.

Speaker 4 Many of the antitrust acts and anti-monopoly policies came from the Republicans.

Speaker 4 By the time we get to McKinley's successor, Theodore Roosevelt, you get a Republican president advocating for a strong interventionist federal government that would promote social justice.

Speaker 4 Or, as Roosevelt himself put it, he believed in, quote, executive power as the steward of the public welfare, end quote.

Speaker 4 So yeah, you know, the Democrats and the Republicans have changed a lot.

Speaker 4 But I'm jumping ahead because William McKinley was not Theodore Roosevelt.

Speaker 4 McKinley perfectly represents the sometimes awkward marriage between socially progressive beliefs and a certain acquiescence to America's moneyed owner class that defined 19th-century republicanism before Roosevelt totally broke the mold.

Speaker 4 Anyway, after returning from the war, William McKinley embarked on a legal career and very quickly got involved with the Ohio Republican Party.

Speaker 4 After studying in the office of a Poland, Ohio lawyer, McKinley attended Albany Law School in New York State, and by 1867, he had been called to the bar and started practicing law in Canton, Ohio, which would become his adopted hometown.

Speaker 4 Almost immediately, the young lawyer got into local politics and started giving speeches stumping for various Republicans.

Speaker 4 At the time, Ohio was considered the ultimate battleground state, which made sense given that it had a traditionally agrarian economy powered by homesteaders and family farms.

Speaker 4 But it was emerging as a new industrial center for the United States.

Speaker 4 Elections in Ohio were always incredibly close. It was the kind of place where Democrats needed to court industry and Republicans needed to ingratiate themselves to the rural working man.

Speaker 4 As such, political strategists of the era started to see Ohio as the key to winning presidential elections.

Speaker 4 If a politician was popular in Ohio, that meant that they could balance the tension between American industry and the small American farmer.

Speaker 4 Sure enough, between 1869 and 1913, Ohio would produce six U.S. presidents, among them William McKinley.

Speaker 4 In the decade between 1867 and 1877, McKinley earned a reputation for being a talented lawyer and an effective speaker.

Speaker 4 He won his first election in 1869 when, as a relatively unexperienced lawyer, he managed to unseat a local Democrat to become the prosecuting attorney of Stark County, Ohio.

Speaker 4 A few years later, he scored some points with the Ohio labor movement when he agreed to defend a group of coal miners who had gotten into a violent clash with strikebreakers.

Speaker 4 Not only did McKinley take the case, which had scared away many other lawyers worried about alienating the mine owners, McKinley got all but one of the miners acquitted, and then he refused to take any money for his legal services.

Speaker 4 Now, was this done out of sympathy for the cause of the miners, or was this a calculating bit of politics?

Speaker 4 Hmm, probably a bit of both, but it's hard to say.

Speaker 4 McKinley certainly used this case to his political advantage in the next year when he ran to represent Ohio's 17th congressional district in the House of Representatives.

Speaker 4

This business-minded son of Ohio ironmen could also claim to be a friend of the working man. Remember when he took that miner's case? He didn't even take a fee.

What a guy.

Speaker 4 It also didn't hurt that McKinley was a war hero with a likably humble demeanor.

Speaker 4 There were other elements of McKinley's personal life that humanized him and made him a genuinely sympathetic figure.

Speaker 4 In 1871, William married the beautiful and spirited Ida Saxton, the well-educated daughter from another well-to-do Canton family. The couple welcomed their first daughter, Katie, that Christmas.

Speaker 4 McKinley lovingly called their first child his favorite Christmas present.

Speaker 4 However, over the next four years, the family would experience a steady stream of tragedies.

Speaker 4 While Ida was pregnant with the couple's second child, her mother passed away suddenly after a short fight with an aggressive form of cancer.

Speaker 4 While she was grieving, Ida suffered a fall and seriously injured her head.

Speaker 4 Now, it's unclear if this fall triggered a form of epilepsy or if the fall was brought on by epilepsy, but Ida would suffer from epileptic seizures for the rest of her life.

Speaker 4 She also sustained a number of infections during that second pregnancy and likely became immunocompromised.

Speaker 4 When she gave birth to the couple's second child, also named Ida in 1873, the infant was sickly.

Speaker 4 The child would only live a few months before dying from cholera.

Speaker 4 Then, if that wasn't already tragic enough, two years later in 1875, the McKinleys lost their oldest daughter, Katie, who succumbed to a bout of scarlet fever.

Speaker 4 These traumatic losses, paired with some very intense physical issues, profoundly changed Ida McKinley.

Speaker 4 Both her mental and physical health remained fragile for the rest of her life, which often left her bedridden and under the close supervision of doctors for long periods.

Speaker 4 William was also crushed by the loss of his daughters, but he remained deeply devoted to Ida and highly protective of her well-being.

Speaker 4 Now, I don't mean to give the impression that William McKinley in any way publicized or exploited these family tragedies. He certainly did not.

Speaker 4 He would have found that kind of thing crass and undignified.

Speaker 4 But when these stories inevitably came out in the press, it only bolstered his reputation as a deeply empathetic and human candidate.

Speaker 4 So it was that William McKinley first went to Washington as a congressman in 1877.

Speaker 4 His old friend and mentor, Rutherford B. Hayes, had just been elected president.

Speaker 4 Hayes, also from Ohio, had just squeaked a victory in one of the closest, brutally contested, and profoundly corrupt elections of the era.

Speaker 4 But that's a story for another day.

Speaker 4 Actually, my friend Mark Chrysler over at the Constant podcast has a fantastic episode on the election of 1876. If you would like to go deeper on that particular story,

Speaker 4 just as both men were about to take office in 1877, Hayes offered the freshman congressman a bit of sage advice on how to be effective in the House of Representatives. Hayes told McKinley:

Speaker 4

To achieve success, you must not make a speech on every motion offered or every bill introduced. You must confine yourself to one thing in particular.

Become a specialist. Why not choose the tariff?

Speaker 4 End quote.

Speaker 4 William McKinley took that advice to heart.

Speaker 4 Specialization was key, and a focus on the sometimes arcane nuances of this particular economic issue was well suited to McKinley's lawyerly analytic approach to politics.

Speaker 4 Tariffs and monetary policy were also fast becoming an important election issue. This was the kind of thing, if handled deftly, that could make the name of an ambitious young politician.

Speaker 4 So, for better or worse, McKinley pursued a course whereby his entire congressional career would be defined by the tariff issue. He was going to be a self-described tariff man.

Speaker 4 So let's pause here. And when we come back, we'll explore McKinley's journey with tariff policy and see what it meant for his political fortunes, America, and the rest of the world.

Speaker 4

Today's episode of Our Fake History is being brought to you by Audible. Now, I love it when Audible supports the show because I actually use Audible.

No joke.

Speaker 4 I use the service all the time to research this podcast.

Speaker 4 Those of you that listen know that I plow through books to research this show, and it's really helpful to be able to listen to some of those books.

Speaker 4 Well, Audible is the service that lets you enjoy all of your audio entertainment in one app.

Speaker 4 They have the best selection of audiobooks without exception, along with popular podcasts and exclusive Audible originals.

Speaker 4 Over the past few months, I listened to The Bronze Lie by Mike Cole to get ready for this series on Sparta. I also listened to Deirdre Bear's Bear's Al Capone biography on Audible.

Speaker 4 I also love the great courses lecture series that are available through Audible. I often go to those lecture series to get an overview of a particular topic that I'll be covering on this show.

Speaker 4

For real, guys, I'm a fan. Start listening and discover what's beyond the edge of your seat.

New members can try Audible now for free for 30 days and dive into a world of new thrills.

Speaker 4 Visit audible.com/slash OFH or text OFH to 500-500. That's audible.com/slash OFH or text OFH to 500-500.

Speaker 4 Today's episode of Our Fake History is being brought to you by Homes.com. If you've ever been in the market for a new home, you know home shopping can be a lot.

Speaker 4 There's so much you don't know and so much you need to know. What are the neighborhoods like? What are the schools like? Who's the agent who knows the listing or neighborhood best?

Speaker 4 And why can't all this information just be in one place? Well, now it is on homes.com. They've got everything you need to know about the listing itself.

Speaker 4 But even better, they've got comprehensive neighborhood guides and detailed reports about local schools. And their agent directory helps you see the agent's current listings and sales history.

Speaker 4 Homes.com collaboration tools make it easier than ever to to share all this information with your family. It's a whole cul-de-sac of home shopping information all at your fingertips.

Speaker 4 Homes.com, we've done your homework.

Speaker 4 William McKinley's congressional career was a mixed bag of successes and setbacks.

Speaker 4 He distinguished distinguished himself early on as a canny political opponent, which put a bit of a target on his back.

Speaker 4 The Democrats and the Ohio legislature even redrew the lines of his congressional district to effectively gerrymander him out of power.

Speaker 4 But to McKinley's credit, he still managed to carry the district after the redistricting. President Hayes would enthusiastically write, quote, he was gerrymandered out and then beat the gerrymander.

Speaker 4 We enjoyed it as much as he did, end quote.

Speaker 4 But the new congressional boundaries would make this district a tight race every time he came up for re-election.

Speaker 4 In 1882, the boundary lines caught up with him, and though the initial vote count had him winning the district by just eight votes, he was eventually forced out of his seat when the result was contested in Congress.

Speaker 4 But this proved to be a short setback. He was back in Washington when the next congressional elections rolled around just two years later in 1884.

Speaker 4 By 1888, McKinley's stature had grown so much within the Republican Party that he was now in the running to become the Speaker of the House.

Speaker 4 While he ultimately did not get that post, As a consolation, he was appointed the chairman of the House Ways and Means Committee, the congressional body in charge of taxation, tariffs, and all other revenue-raising measures.

Speaker 4 Now, Kinley was genuinely excited about this appointment as it capped a more than decade-long congressional career that had been defined by his advocacy for protective tariffs.

Speaker 4 Being the chairman of the body that controlled tariffs, well, that was a dream job.

Speaker 4 Okay,

Speaker 4 so let's crack open the stinky egg of late 19th century economic policy, shall we?

Speaker 4 Now,

Speaker 4 if there's a historical myth floating around in the public discourse about the late 19th century right now, it's that it was a time of beautiful, uninterrupted prosperity for the United States.

Speaker 4 You may have heard that in the 1880s and 1890s, America was rich.

Speaker 4 Well,

Speaker 4 as you might have guessed, the truth is considerably more complicated.

Speaker 4 After the end of the American Civil War, the United States started industrializing at a rate that had never been experienced in that nation's history.

Speaker 4 This sometimes gets called the Second Industrial Revolution. America's manufacturing was exploding and railways were being built at a dizzying pace.

Speaker 4 This went hand in hand with greater demand for raw materials like coal and iron ore, which of course led to a huge expansion of American mining.

Speaker 4 All of this meant that by the 1880s, the United States was vying to replace Europe, and in particular Great Britain, as the so-called workshop of the world.

Speaker 4 There's no denying that in this period, American industry was on the grow.

Speaker 4 But that is only one part of the story. This was also an age of economic volatility.

Speaker 4 The American economy was growing, but it was happening in a series of convulsive booms and busts that were harrowing to live through, especially if you were an industrial worker or a small farmer.

Speaker 4 When William McKinley was first elected to Congress in 1877, the United States was just starting to recover from a severe economic depression set off by a stock market crash and a series of bank failures known as the Panic of 1873.

Speaker 4 Manufacturing had expanded so quickly that a crisis of overcapacity had been created.

Speaker 4 Railroads, which had been built using borrowed money, had now outpaced the demand of riders, especially as the economy retracted.

Speaker 4 The over-leveraged J.

Speaker 4 Cook and Company banking concern had bet big on railways and failed in 1873, which created a crisis in confidence in the entire banking system as panicked Americans tried to withdraw their savings all at once.

Speaker 4 Within a year of this crisis, 60 American railway companies had gone bankrupt and the country slipped into a deep depression.

Speaker 4 While the panic of 1873 was one of the most significant of the era, it was not the only financial panic.

Speaker 4 In 1882, America slipped again into a deep recession, which was capped by another panic in 1884.

Speaker 4 This was followed by panics in 1890, 1893, and 1896.

Speaker 4 Every few years, America's financial system was on the brink of collapse.

Speaker 4 So, all of this is to say that despite the fact that American industry was growing and the country was emerging as an economic powerhouse that could rival the great European empires, average Americans found themselves living through deep recessions and full-on economic depressions for good chunks of the 1870s, 80s, and 90s.

Speaker 4 The volatile economic reality of the late 19th century opened new fault lines in American politics.

Speaker 4 The United States was already divided between North and South, but economic tensions of this period drew an even sharper divide between urban and rural America, not to mention increasing tensions between America's laborers and the owners of American capital.

Speaker 4 In this period, America's millionaires became infamous for what the pioneering sociologist Thorstein Velbin would dub conspicuous consumption.

Speaker 4 Starting in the 1870s, New York's Fifth Avenue became Millionaire's Row, with American industrialists and financiers like the Carnegies and the Vanderbilts vying to build yet more opulent mansions on the thoroughfare.

Speaker 4 However, the wealth being generated by the growing American economy was not making its way to the people whose labor were powering the industrial transformation.

Speaker 4 While there were certainly rich Americans who lost it all during these various economic crashes, many of America's richest people seemed to be insulated from the volatility of the American economy.

Speaker 4 In the years of depression or economic contraction, it was the workers who bore the brunt of it. Wage cuts, layoffs, expanded work weeks, and inhumane working conditions were the norm.

Speaker 4 There was simply no such thing as job security in this period.

Speaker 4 As such, the late 19th century was characterized by labor action, strikes, and sometimes violent clashes between disgruntled workers and forces loyal to the owners.

Speaker 4 There was the Great Railroad Strike of 1877, the Camp Dump Strike of 1883, the Great Railroad Strike of 1886, the Coal Creek War, the Homestead Strike of 1892, just to name a few of the big labor actions.

Speaker 4 There were dozens more.

Speaker 4 These strikes could often turn violent when unionized workers were confronted by either the state militia or owner-hired mercenaries.

Speaker 4 Blood was spilled in these fights that often hinged on issues like living wages or an eight-hour workday.

Speaker 4 People died for this stuff.

Speaker 4 So it was in the context of boom-bust capitalism and bloody labor disputes that what might seem like arcane debates about monetary policy became some of the defining political issues of the day.

Speaker 4 One of the most heated debates was around the question of what metals, if any, should back American currency.

Speaker 4 Should America be on the gold standard or should the currency be backed by a combination of gold and silver?

Speaker 4 Now, if you'll allow it, I'm going to set that complicated but very important issue aside just for a moment so we can concentrate specifically on tariffs.

Speaker 4 Tariffs were the other key part of the economic debate, and they were the part of the equation that William McKinley staked his political career on.

Speaker 4 So, as many of you know, tariffs are taxes paid to the government by importers on items brought in from foreign markets.

Speaker 4 As a taxation tool, tariffs were used to achieve different goals in different periods. For a good part of the 19th century, tariffs were the primary way that the American government funded itself.

Speaker 4 Remember, this was a time before income tax, and as such, tariffs were often presented as a means to fund big government projects like infrastructure and what have you.

Speaker 4 However, tariffs could also be used to protect various domestic businesses.

Speaker 4 Tariffs can be used to make foreign goods more expensive for the consumer, as the cost of the tariff inevitably gets passed on from the importer on to the buyer.

Speaker 4 This allows domestic producers to sell their goods more cheaply and hopefully drives down demand for foreign goods.

Speaker 4 But here's the thing about tariffs that often gets left out of the conversation we're having today:

Speaker 4 you can't use tariffs for both protectionist purposes and for money raising purposes at the same time.

Speaker 4 If you want your tariffs to raise funds, then they can't be set so high as to drive down demand for foreign products.

Speaker 4 If demand gets too low, then you're not going to make much money off of those tariffs.

Speaker 4 But if the goal is to drive down demand for foreign products, great, just don't expect to make money at the same time. One or the other.

Speaker 4 Now, interestingly, tariffs have been a wedge issue in American politics since the time of George Washington. But after the Civil War, they became especially contentious.

Speaker 4 In the immediate aftermath of the war, tariffs were used as a means to fund the government steeped in war debt.

Speaker 4 They also helped finance one of the few government spending programs of the era, and that was paying the pensions of Union soldiers. This made tariffs deeply unpopular in the American South.

Speaker 4 Firstly, southern planters were among the biggest importers of foreign goods that were simply not being manufactured in the South.

Speaker 4 Secondly, American cotton, tobacco, and sugar farmers were some of America's biggest exporters.

Speaker 4 Tariffs on foreign goods made it harder to export, as potential trading partners usually responded with reciprocal tariffs.

Speaker 4 There was big demand for American cotton, sugar, and tobacco in Europe, and the tariffs got in the way of this trade.

Speaker 4 Finally, people who fought for the Confederacy were not entitled to the soldiers' pensions that the tariff revenues were funding.

Speaker 4 During William McKinley's time as a congressman, he advocated for tariffs as a means to protect domestic industry and decrease government revenues. Yes, you heard that right, decrease revenues.

Speaker 4 Now, this might be hard to believe in a 21st century context, but in the 1880s and early 1890s, the government was actually bringing in far more money than it was spending.

Speaker 4 Now, this might sound like a good problem to have, but these government surpluses were a problem because it meant that the money was getting stuck in the U.S.

Speaker 4 Treasury and was not recirculating in the American economy. Now, this was obviously in an age before there were expensive social programs to fund.

Speaker 4 But it was straight up bad for the American economy for the government to hold on to the surplus. The government either needed to spend more or take in less.

Speaker 4 So, how do you deal with this surplus? Well, the Democrats advocated for cutting the tariffs. The tariff was a tax, after all, and who doesn't like a tax cut?

Speaker 4 But the Republicans, led by William McKinley, argued just the opposite. If tariffs were set considerably higher, then revenue would come down as demand for foreign goods dropped.

Speaker 4 You would collect fewer tariffs as fewer things were being imported. The tariffs would also protect American industry from foreign competition.

Speaker 4 So, the folks who really supported tariffs in this period tended to be American industrial manufacturers who were still catching up to their international, mostly British, competitors.

Speaker 4 These were people like William McKinley's father, who, I'll remind you, owned Ohio iron foundries.

Speaker 4 These American industries were selling most of their products domestically anyway. High tariffs helped these very specific business people get an edge on their competition.

Speaker 4 So, Northeastern American industrialists liked high tariffs. Farmers from the American South and the largely agrarian American West did not.

Speaker 4 They felt like they were the ones paying these tariffs as a consumer tax and were receiving none of the benefits. For the small farmer, tariffs had made life more expensive.

Speaker 4 And for the big planter, they made exporting more difficult.

Speaker 4 But William McKinley wagered his political career on the idea that high tariffs were ultimately the best choice for American prosperity.

Speaker 4 And it's here that I actually started to notice some subtle differences in the various McKinley biographies I was reading.

Speaker 4 Scott Miller, author of The President and the Assassin, and Robert Mary, author of President McKinley, both acknowledged that McKinley's tariff policy was deeply beneficial to a very specific group of American business owners and industrialists.

Speaker 4 But in the triumph of William McKinley, Carl Rove goes out of his way to write, quote, the major, that is McKinley, supported protection because it meant decent wages for labor.

Speaker 4 not because it helped wealthy businessmen, end quote.

Speaker 4 Now to be clear, McKinley certainly pitched high tariffs as a means of guaranteeing high wages.

Speaker 4 I mean, the logic follows, if products made from cheap foreign labor are kept out of the American market, then American companies will not need to lower their wages to remain competitive.

Speaker 4 It's not naive to say that McKinley sincerely believed that his policy would ultimately benefit the American worker.

Speaker 4 But it is naive to suggest that he didn't also want to help wealthy businessmen because

Speaker 4 he absolutely wanted to help wealthy businessmen. And as we shall see as this series progresses, the American business community took note.

Speaker 4 But it's interesting to me that Karl Rove chose to softpedal that in his biography.

Speaker 4 Anyway, in 1888, after William McKinley secured the chairmanship of the Ways and Means Committee, he set about drafting the most ambitious set of tariff hikes and new tariffs in the nation's history, until

Speaker 4 recently.

Speaker 4 And here's the thing. As tariffs have recently roared back into relevancy, McKinley quotes have been resurfacing and have been used as evidence that tariffs are real boons for the economy.

Speaker 4 The context that often gets left out is that the quotes that are being used from McKinley were part of his sales pitch for a deeply controversial tariff bill.

Speaker 4 For instance, in his biography of McKinley, Robert Mary points to the congressman claiming in 1890 that, quote, we lead all nations in agriculture, We lead all nations in mining.

Speaker 4

We lead all nations in manufacturing. These are the trophies we bring after 29 years of the protective tariff.

Can any other system furnish such evidence of prosperity? End quote.

Speaker 4 Now, taken on its own, that quote seems like a ringing endorsement of tariffs.

Speaker 4 But Mary continues, quote, critics pointed out that there wasn't much of a cause and effect relationship between protectionism and American prosperity. Senator John B.

Speaker 4 Allen of Washington argued that many other factors contributed to America's expanding growth, end quote.

Speaker 4 That senator very correctly pointed out that the boom-bust cycles of the past 25 years had demonstrated that, quote, prosperity and adversity have come alternately under both high and low tariffs, end quote.

Speaker 4 So

Speaker 4 let's not mistake McKinley's political sales pitch for a historical reality.

Speaker 4 Nevertheless, the Republican majority in Congress meant that McKinley was able to create an incredibly ambitious tariff act.

Speaker 4 The bill raised tariffs on almost all foreign products, averaging out to a rate of about 50%.

Speaker 4 Now, there were certain provisions in this bill meant to win over American farmers, who, as I mentioned earlier, were among the biggest opponents of high tariffs.

Speaker 4 McKinley hoped that maybe a set of tariffs just for them would get them on board with this broader tariff program.

Speaker 4 As such, the bill slapped a big tariff on foreign agricultural products, particularly those being imported from Canada. More on that in a second.

Speaker 4 The bill also carved out a special place for sugar, keeping the tariffs low on that product to hopefully encourage its export to Europe. So, big tariffs on foreign foods and a carve-out for sugar.

Speaker 4 Now,

Speaker 4 a word on the Canada of it all, because as a Canadian, what I learned really blew my mind.

Speaker 4 There were some in the Republican administration in 1890 who hoped that McKinley's new protectionist tariff bill would ultimately result in Canada being annexed as an American state.

Speaker 4 I swear to God, I'm not making this up. Everything old is new again.

Speaker 4 Now, to be clear, the annexation of Canada does not seem to have been one of William McKinley's main priorities.

Speaker 4 The bill was not designed specifically to force Canada into the Union, but there were a handful of American leaders who hoped this might happen.

Speaker 4 Chief among them was the Secretary of State James Blaine, who eventually came on as one of the tariff bill's co-authors, that is, after decrying an early version as, quote, an infamy and an outrage, end quote.

Speaker 4 But he eventually came around to the bill when he saw its potential benefits. Now, as I mentioned, the tariff bill went hard against Canadian agricultural products, in particular, grain.

Speaker 4 James Blaine assumed that the loss of the American market would have Canadians clamoring to become American to get around the tariff wall.

Speaker 4 He said publicly that he believed that, quote, a grander and nobler brotherly love may unite in the end the United States and Canada in one perfect union, end quote.

Speaker 4 He also declared that he, quote, opposed to giving the Canadians the sentimental satisfaction of waving the British flag and enjoying the actual remuneration of American markets, end quote.

Speaker 4 Fascinating. How dare these Canadians trade with Americans while not actually being American?

Speaker 4 According to the historian Mark William Palin, Blaine also privately told then-President Benjamin Harrison that he believed the harsh tariff measures would force Canada to, quote, ultimately, I believe, seek admission to the Union, end quote.

Speaker 4 Yes, the Secretary of State thought that economic force would ultimately end Canadian sovereignty.

Speaker 4 You see,

Speaker 4 James Blaine made the same faulty assumption that so many American empire builders have made throughout history, and that is that Canadians have no real identity.

Speaker 4 We're just dying to become Americans so long as we're given enough of a nudge.

Speaker 4 Well, that was not true in 1776, or in 1812, or in 1890, or in 2025.

Speaker 4 Now, in the United States, James Blaine's hope that the tariff bill might lead to a Canadian state was only barely discussed in the news media.

Speaker 4 But in both Britain and Canada, these remarks were taken incredibly seriously.

Speaker 4 Canadian nationalists immediately responded, calling the bill a quote, heavy blow struck alike at our home industries and at the prosperity and independence of the Dominion of Canada, an unprovoked aggression, an attempt at conquest by fiscal war.

Speaker 4 End quote. Similarly, the British politician Lion Playfair called the law a, quote, covert attack on Canada, end quote.

Speaker 4 He further worried that if the McKinley bill was meant to, quote, force the United States lion and the Canadian lamb to lie down together, this can only be accomplished by the lamb being inside the lion, end quote.

Speaker 4 In 1891, this became a huge election issue in Canada. And I've always been skeptical about the idea that history repeats itself,

Speaker 4 but my God, in this case, history has really repeated itself.

Speaker 4 In 1891, then-Canadian Prime Minister Sir John A. MacDonald made the threat of American annexation a key part of his re-election pitch.

Speaker 4 Specifically, he charged the opposition party with being involved in, quote, a deliberate conspiracy by force, by fraud, or by both, to force Canada into the American Union. End quote.

Speaker 4 McDonald would end up winning re-election in what proved to be an incredibly tight race.

Speaker 4 If you are not Canadian, then you may not know that our recent 2025 federal election was deeply colored by American tariffs and threats of annexation.

Speaker 4 And much like in 1891, a surprising political comeback was fueled by worries that Canada's sovereignty was under threat.

Speaker 4 Now, ultimately, the 1890 McKinley tariffs did not cripple the Canadian economy, nor did they inspire a movement for American statehood.

Speaker 4 Instead, the bill inspired a new strain of anti-American sentiment in Canada and led to the country making closer economic bonds with Great Britain.

Speaker 4 With America retreating as an exporter of agricultural products, Canada stepped in to fill some of the void. In this way, the McKinley bill ironically helped Canadian exports.

Speaker 4 Canadian produce and animal exports grew from $16 million to $24 million a year in the years that followed the bill.

Speaker 4 Canadian agricultural exports to Britain specifically jumped from $3.5 million a year to $15 million a year.

Speaker 4

Now, as a Canadian, this fascinates me deeply. But I'm sure many of you are wondering what this massive tariff bill meant for the American economy.

Well,

Speaker 4 it seems to have been a bit of a mixed bag.

Speaker 4 It neither generated an economic boom, nor did it completely wreck the American economy, as detractors had warned. There were price rises associated with the bill, however.

Speaker 4 As historian Robert Mary points out, quote, opponents predicted big increases in prices, and clever tradesmen exploited the opportunity to raise prices even before the Tariff Act could have any real impact, end quote.

Speaker 4 So, according to Robert Mary, the assumption that tariffs were going to raise prices led to some unscrupulous business practices. But did the McKinley tariffs raise prices in the long run?

Speaker 4 Well, they did on some items, but according to a government study done in 1891, the McKinley tariffs did not meaningfully increase the cost of living in the United States.

Speaker 4 So, while the tariffs were not destructive to the American economy, they also did not yield many tangible benefits.

Speaker 4 Significantly, they did little to help the plight of American farmers, who had always been skeptical of the high tariff program.

Speaker 4 One of the big issues for American farmers was that the price of crops had been depressed for years.

Speaker 4 Despite the hopes of William McKinley, the tariffs on agricultural imports did very little to remedy this problem.

Speaker 4 But gauging the effectiveness of the McKinley tariffs is particularly difficult given the other economic factors of 1890.

Speaker 4 Before the bill could take effect, the American economy slumped into another recession following the so-called Panic of 1890. The panics just kept coming, people.

Speaker 4 Now, rightly or wrongly, McKinley's aggressive tariff package was blamed for this economic slowdown. And, unfortunately for McKinley, it was a congressional election year.

Speaker 4 Tariffs had always been controversial.

Speaker 4 And the fact that there was an economic downturn right at the moment that the tariff package was passed, well, this made Republicans vulnerable at the ballot box.

Speaker 4 Sure enough, McKinley's tariffs and many American congressmen were rejected by American voters during the 1890 midterm elections.

Speaker 4 The Democrats took a commanding majority in the House of Representatives with 283 seats. The Republicans took just 86, which constituted a loss of 93 congressional seats.

Speaker 4 McKinley was one of those representatives who was sent packing.

Speaker 4 Let it be known, tariffs nearly ended William McKinley's political career.

Speaker 4 In 1890, the major was down, but he was far from out.

Speaker 4 McKinley would orchestrate an impressive political comeback that would lead him all the way to the White House. All it took was the help of some very wealthy men.

Speaker 4 Okay,

Speaker 4 that's all for this week. Join us again in two weeks' time when we will continue our look at President William McKinley.

Speaker 4 Before we go this week, as always, I need to give some shout-outs: big ups to Layton Williams, to Ron Salazar,

Speaker 4 to Philip Haken,

Speaker 4 to Kenzie Gordon, to Jack Granado, to Chelsea Sweetman, to Bradley Hansen,

Speaker 4 to Ian Kohler,

Speaker 4 to Stephen Kilchren,

Speaker 4 to Filippo,

Speaker 4 to Christy Kurtzinger, to Justin Gazda, to Matt Mischler,

Speaker 4 to Ian Luna,

Speaker 4 to German Jobber,

Speaker 4 to Reed Putnell, to Ted Fisher, to Adam Welvang, to Messian Tilmatine, to Ram33,

Speaker 4 to Sequoia, to Ben Cohen, Cohen, to Rangasai Vararagavan, to Kyler Moltson, to Henry, to Orion Gilliam, to Jonathan McDowell, to Cecilia Tsang, and to Pete Spearin.

Speaker 4 All of these folks have decided to pledge at $5

Speaker 4

or more every month on Patreon. So you know what that means.

They are beautiful human beings.

Speaker 4 Thank you, thank you, thank thank you for your continued support of this show i absolutely could not do it without the support of the patrons i love you all when i wrap up this series on mckinley i will be doing another bonus show where i will be answering questions about this topic so if you have questions for me you can send me an email at our fake history at gmail.com or if you're a patron go to the patreon chat area and ask your question there.

Speaker 4

I can also be found on Facebook, facebook.com slash our fake history. I can be found on Instagram at our fake history.

I can be found on TikTok at OurFake History.

Speaker 4

I can be found on Blue Sky at Ourfake History. I can be found on YouTube.

I'm out there on the social media, baby. I love hearing from you folks, so please do not hesitate to reach out.

Speaker 4 Your messages make my day.

Speaker 4 As always, the theme music for the show comes to us from Dirty Church. Check out more from Dirty Church at dirtychurch.bandcamp.com.

Speaker 4

And all the other music you heard on the show today was written and recorded by me. My name is Sebastian Major.

And remember, just because it didn't happen doesn't mean it isn't real.

Speaker 4 This summer, Pluto TV is exploding with thousands of free movies. Summer of cinema is here.

Speaker 4 Feel the explosive action all summer long with movies like Gladiator, Mission Impossible, Beverly Hills Cop, Good Burger, and Transformers Dark of the Moon.

Speaker 4

Bring the action with you and stream for free from all your favorite devices. Pluto TV.

Stream now, pay never.

Speaker 5 Hey, it's James Albacher. I've been an entrepreneur, investor, best-selling writer, stand-up comic, and whatever it is I'm interested in, I get obsessed.

Speaker 5

Yes, it's led to success, but it's also led to such heartbreaking failure. I have failed more times than I can count.

I wish in my life I had had people to talk to.

Speaker 5 That's why I started the James Altiser show and bring on some of the most brilliant minds in every area of life. People like Richard Branson, Sarah Blakely, Mark Cuban, Danica Patrick, Gary Kasproth.

Speaker 5 And I wanted to find out exactly how they've navigated the highs, the lows, and everything in between. No fluff, just raw stories and real advice.

Speaker 5 I've talked to 1500 of the most amazing people on the planet.

Speaker 5 So if you want to learn from the best and skip the same old canned interviews, we're all about helping you find your next big idea, level up your thinking, and ultimately to choose yourself.

Speaker 5 So let's do this together. Subscribe now to the James Alpiter Show.

Speaker 6 The clock is ticking to get the most of your summer behind the wheel of the upscale all-electric Jeep Wagoneer S and innovative Chrysler Pacifica plug-in hybrid.

Speaker 6 And right now, get 0% financing for 72 months on the 2025 Chrysler Pacifica plug-in hybrid and the 2025 Jeep Wagoner S. Plus you may qualify for up to a 7,500 federal tax credit.

Speaker 6 See your California Jeep brand dealer and California Chrysler dealer today. Finance offer not compatible with any other offer.

Speaker 6 0% APR financing for 72 months equals $13.89 per month per 1,000 financed for well-qualified buyers through Stellantis Financial, regardless of down payment. Not all customers will qualify.

Speaker 6

Contact dealer for details. The federal tax credit is offered by a third party and is subject to change without notice.

Please confirm this information to ensure its accuracy and availability.

Speaker 6 Consult the tax professional for details and eligibility requirements. Income and other restrictions may apply.

Speaker 6 Purchases are not eligible if the customer exceeds adjusted gross income limitations: $300,000 for married filing jointly taxpayers, $225,000 for head of household filers, and $150,000 for single-filers.

Speaker 6 Offers end September 30th. Chrysler and Jeap are registered trademarks.