The Lonely Work of a Free-Speech Defender

Over the past year, the federal government has taken a series of actions widely seen as attacks on the First Amendment.

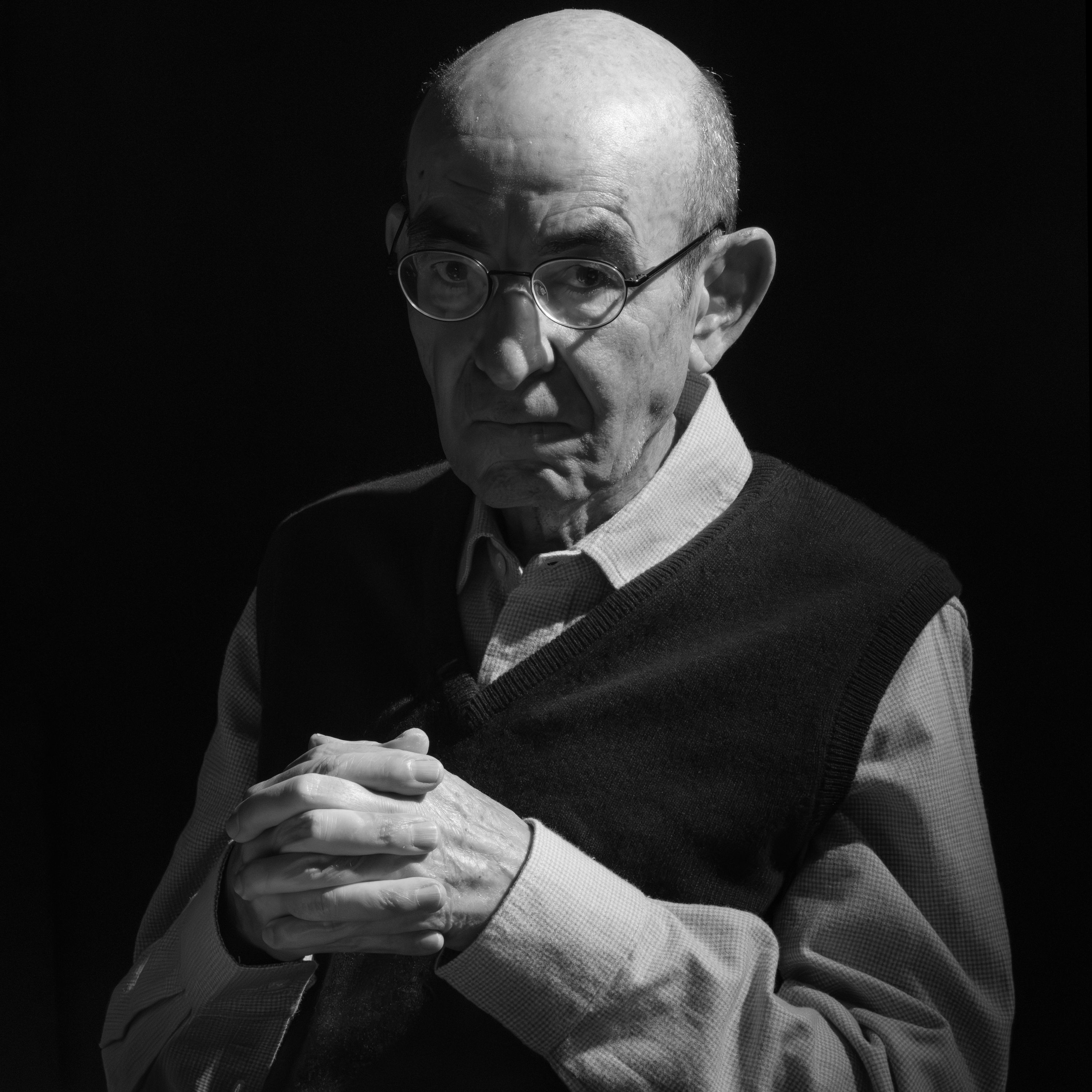

Greg Lukianoff, the head of a legal defense group called the Foundation for Individual Rights and Expression, speaks to Natalie Kitroeff about what free speech really means and why both the left and the right end up betraying it.

Press play and read along

Transcript

Speaker 1 Brought to you by the Capital One Saver Card. With Saver, you earn unlimited 3% cash back on dining, entertainment, and at grocery stores.

Speaker 1 That's unlimited cash back on ordering takeout from home or unlimited cash back on tickets to concerts and games. So grab a bite, grab a seat, and earn unlimited 3% cash back with the Saver card.

Speaker 1

Capital One. What's in your wallet? Terms apply.

See capitalone.com for details.

Speaker 2 From the New York Times, I'm Natalie Kitroff.

Speaker 3 This is the Daily.

Speaker 4 After years and years of illegal and unconstitutional federal efforts to restrict free expression, I will also sign an executive order to immediately stop all government censorship and bring back free speech to America.

Speaker 2 President Trump began his term with a promise. He would restore free speech in America after what he said were the left's attempts to limit it.

Speaker 4 Never again will the immense power of the state be weaponized to persecute political opponents.

Speaker 2 But over the past year, the federal government has taken a series of actions widely seen as direct attacks on the First Amendment.

Speaker 5 Trump threatened to deport non-citizen college students and other international visitors who take part in pro-Palestinian protests.

Speaker 3 Donald Trump declared on social media that comedian Seth Meyers' jokes about him were, quote, 100% anti-Trump, which is probably illegal.

Speaker 2 Moves that supercharged a furious debate over free speech in the United States. A staunch proponent of free speech, Charlie Kerr openly debated hot button issues.

Speaker 2 But in the wake of his death, that fundamental right is being challenged.

Speaker 2 If you're going to spread hateful shit and you're going to target marginalized groups of people, don't be all, oh my God, I've been shot.

Speaker 3 When you see see someone celebrating Charlie's murder, call them out. And hell, call their employer.

Speaker 2 You believe in canceling and deplatforming people who platform people that you do not like. And that goes against all of the principles of conservatism.

Speaker 2 So this fall, I spoke with Greg Lukianoff, the head of a legal defense group called the Foundation for Individual Rights and Expression, or FIRE.

Speaker 2 Greg has taken on high-profile cases that have pitted him and his organization against progressive campus culture and the Trump administration.

Speaker 2 And in the process, he's made a name for himself as a free speech true believer.

Speaker 2 We talked about what freedom of speech really means and why both the left and the right end up betraying it.

Speaker 2 It's Friday, December 5th.

Speaker 3

Greg. Hi.

Is it better if I have my headphones on or do you care?

Speaker 2 In many ways, Greg Lukianoff is not what you'd expect when you picture the kind of lawyer who's gone to battle with some of the most powerful politicians and institutions in the country.

Speaker 3 James always had this never look the part ethos, which was like, listen, if I'm going to a rave in Eastern Europe, I'm wearing like a lumberjack shirt.

Speaker 2 The child of a British mother and a Russian father, he comes from a working class background in Connecticut.

Speaker 3 And I had a train running through my backyard. So I grew up in like the poorer part of town in an immigrant neighborhood.

Speaker 2 And to him, the First Amendment isn't just a constitutional framework.

Speaker 3 Well, I've kind of built my life around this thing.

Speaker 2 But more of a philosophy on which he's based his life.

Speaker 2 When you see the issue of free speech the way Greg does, it's everywhere. And because of that, our conversation ended up surprisingly wide-ranging.

Speaker 2 It started with an email where we asked to pick his brain.

Speaker 3 Someone was trying to popularize the idea that it's rude to say that you want to pick someone's brain.

Speaker 2

Actually, yeah. See, that's a free speech issue I can get behind.

We should be able to say, I want to pick your brain, you know?

Speaker 3 I was just like, okay, guys, like my mother's British. So I got like these kind of like semi-Victorian norms kind of shoved down my throat.

Speaker 3 And it's kind of like, can't just try to figure out what people are trying to say.

Speaker 3 The polite censorship is often kind of like what I jokingly call like the

Speaker 3

British way of handling conflict, which is to say that we won't discuss it at the dinner table. And it's like, no, that actually doesn't solve anything, Mom.

Yeah, yeah.

Speaker 2 It is interesting, you know, to start off the conversation this way, because it does sound like you have in some way been thinking about this stuff for a very long time.

Speaker 2 It's been central to your life for a very long time.

Speaker 3 It's my, it's my second earliest memory, actually.

Speaker 2 Which is, what is the second earliest?

Speaker 3 It was Christmas when I was four.

Speaker 3

And my auntie Rona had got me a gift. And I opened it up and it's this absolutely terrible cheap plastic drum.

Uh-oh.

Speaker 3

And it's the kind of thing that when you hit it, it's like tonk, tonk. Like it didn't even make a drum sound.

Like,

Speaker 3 yeah, yeah. I later found out it was a joke gift because Rono was picking on my mom like a good friend should, but for the idea that like, ha ha, I got your son a drum, you know,

Speaker 3 to ruin your life.

Speaker 3

But I wasn't in on the joke. And you were just a kid getting a kind of terrible gift.

Lousy gift. Yeah.

Speaker 3 And it was the first time in my life, at least, that I could remember that I got a gift I didn't genuinely like and feel appreciative about.

Speaker 3 And I remember like looking at my mom and being like, I have to be polite. And like looking at my dad and being like, I have to be honest, because Russian is much more brutal honesty, you know, like

Speaker 3 to be like, I do not like it.

Speaker 2 Yeah, you have an angel and a devil on your shoulder when it comes to free speech. I see.

Speaker 3 But here's the thing, though, like, what's the, which is which sometimes? You know, like, it can be hard to to tell. So I look back and forth, back and forth, back and forth.

Speaker 3 And then I'm like, and I break into tears, you know, because I don't know what to do. So it took me a while.

Speaker 3 I always told the story of crying about that without realizing it had a free speech intersection as well. The idea that you can't be both polite and honest sometimes.

Speaker 3 And between the two, honesty is more important.

Speaker 2 Before we go any further, I want to just ask if you can give me your definition of what free speech is and what it isn't.

Speaker 3

Sure. So freedom of speech, you know, I have a pretty simple definition of it.

Freedom of speech is to be able to think what you will and say what you think.

Speaker 3 Like just that radical, you know, just that expansive.

Speaker 3 I sometimes say that the purest form of speech is expression of your opinion and the worst form of censorship is called viewpoint discrimination, saying that everyone else is allowed to make their arguments, but if you have this viewpoint, you are forbidden.

Speaker 3 That's the heart of darkness for freedom of speech.

Speaker 3 And actually, there is one thing worse, compelled speech, not telling people just what they can't say, but telling people what they must say, because that's totalitarian.

Speaker 2 I'm wondering if you can just take us through what you think, as you think about your own personal history, what led you to defending free speech?

Speaker 3 I would definitely say it's a combination of disposition and upbringing, you know, are probably the two most decisive factors there.

Speaker 3 And that I do think I have this very hardwired like discomfort with conformity and with authoritarianism. Now, am I like some kind of like radical non-conformist in a lot of ways?

Speaker 3

No, I just have to be very clear that I'm choosing this stuff myself. Right.

You know, like I actually am deeply uncomfortable in sports stadiums.

Speaker 2 Because of this?

Speaker 3 There's something about

Speaker 3

being in a crowd and cheering along with them that it makes me profoundly uncomfortable. Like I had to, I have to leave.

Like I tried to go to a baseball game with my son and I just couldn't do it.

Speaker 3 It's unnerving somehow. I think that's the, it might be some kind of genetic predisposition that

Speaker 3 led Lukyanovs to flee to Toltar.

Speaker 2 Well, that's what I was going to say. I was wondering if it had anything to do with this idea from the history you inherited.

Speaker 2 I mean, the kind of Soviet experience, the desire to not be in a place where everybody's chanting the same thing over and over again.

Speaker 3 I find it so uncomfortable. But I have noticed that the one thing that a lot of civil libertarians have in common is that we can be very nice people in some cases, sometimes, but not always.

Speaker 3 But we all have an issue with authority.

Speaker 2 After graduating from Stanford Law in 2001, Greg joined FHIR, which was then a small nonprofit based in Philadelphia. It had a staff of just six people.

Speaker 3

It was me, who was almost like a boringly stereotypical left-leaning atheist burning man attendee, you know, back when it was cool. Sure.

And

Speaker 3 we had a full-blown Marxist.

Speaker 3 We had a very middle-of-the-road

Speaker 3 Democrat dude.

Speaker 3 We had a

Speaker 3 conservative Catholic and an evangelical Christian.

Speaker 3 And

Speaker 3 it was funny because I had to face some of my own prejudices because I was surprised that the person who was the most interested in hearing us say what we thought and argue things was actually the evangelical Christian.

Speaker 3 She encouraged us to have debates about the existence of God.

Speaker 3 I was changed by your friendship, to be honest. Like it was something I realized that I had my own sort of simple-mindedness about this stuff.

Speaker 3 And what's funny is the Marxist has become since quite conservative. The Catholic has become quite liberal.

Speaker 2 The wonders of free speech or the wonders of working in a free speech organization office of six people, I guess.

Speaker 3 But because it was post-9-11, we had a lot of really unsympathetic cases coming through for my first cases. Like what?

Speaker 2 Give me an example.

Speaker 3 So there was this guy, Sami Al-Aryan at University of South Florida. And the rumors was that he had actual ties to, I believe, the Muslim Brotherhood.

Speaker 2 One of the first cases Greg took on at fire centered on a professor at the University of South Florida named Sammy Al-Aryan.

Speaker 2 The university had threatened to fire Al-Aryan after an old clip surfaced of him saying the phrase, death to Israel.

Speaker 3 So this is clear First Amendment case as far as I was concerned.

Speaker 2 Fire succeeded in helping prevent the university from firing al-Aryan for his comments. But the professor was later indicted for having links to Islamic terrorists.

Speaker 2 And so while the case represented a win for FIRE on free speech grounds, it came at a cost.

Speaker 3

And we lost donors during this thing. We got all sorts of hate mail.

I got all sorts of death threats. Wow.

Speaker 3 You know, which honestly is good training for an up and coming First Amendment lawyer, but it was unpleasant, shall we say?

Speaker 2 Yeah, trial by fire.

Speaker 3 Yeah, it was, ah, nice. It's hard when your name is fired, innit?

Speaker 2 Greg said this case taught him a basic truth about his new job.

Speaker 2 Defending the First Amendment would inevitably make him more enemies than friends. That were willing to drive this bus into a wall rather than that would eventually take a personal toll.

Speaker 2 So I want to talk about

Speaker 2

what happens after you become the president of the organization in 2006. This is about five years later.

Yeah.

Speaker 2 You've talked about how your own experience with depression and with therapy has kind of informed how you approach your work.

Speaker 2 Can you tell me about that? Because I think that is fascinating.

Speaker 3 Sure.

Speaker 3 In December of 2007, I had to check myself in as a danger to myself because I'd been, you know, I went to the hardware store to try to find stuff to kill myself.

Speaker 3 So you were in a, yeah, a really dark place. Really dark place.

Speaker 3 And a lot of this was culture war stuff, you know, like a lot of it was, you know, I was dating someone and she liked the fact that I defended people on the left.

Speaker 3 She didn't like the fact that I defended people on the right.

Speaker 3

And I remember actually saying to her, listen, I'm an old school ACLU guy. I'm willing to defend the rights of Nazis.

I'm certainly going to defend Republicans.

Speaker 3 And she said to me, Republicans might be worse. Wow.

Speaker 3 And then I also had two different scenarios where I got in arguments with conservatives at bars and, you know, very nearly came to blows because they were mad at me about my defending lefties.

Speaker 3 And that's kind of what my whole life felt like for years. And it's exhausting.

Speaker 2 yeah i mean the work and the way you approach it i mean it sounds like that's the only way you could have ever approached it but it also is a recipe for loneliness yeah it really was and so i start doing cognitive behavioral therapy

Speaker 3 and kind of the whole idea is that you can intervene

Speaker 3 in the space between

Speaker 3 thinking and feeling.

Speaker 3 And I was studying Buddhism at the time and very interested in ways to sort of like step outside and see your thoughts kind of happening sort of like in front of you.

Speaker 3 But really feeling the experience of talking back to the,

Speaker 3 I wouldn't put this for anyone else's brain, but the crazy voices in my head

Speaker 3

that were so incredibly self-critical. Like, for example, I tried to kill myself.

I'm that kind of person who gets clinically depressed. No one's ever going to love me.

Speaker 2 And the intervention is.

Speaker 3

The intervention is to look at it and be like, that's catastrophizing, you know, and then to rationally analyze it. I actually haven't done CBT on that particular thought.

So it's a little emotional

Speaker 3 to think that one through because I really, that one stuck with me, you know, like the idea that

Speaker 3 when people know you were broken, you know, can they ever invest in you again? You know,

Speaker 3 but you can, CBT helps you calm that thought down,

Speaker 3 not with the power of positive thinking, but with just rational analysis, you know? Yeah.

Speaker 3 And there was this moment in like September or October of 2008

Speaker 3 where

Speaker 3 I had all of these horrible, you know, thoughts popping up in my head.

Speaker 3 And they just didn't really sound particularly true anymore.

Speaker 3 And it was transformative. Like it was just like, oh my God, like they don't,

Speaker 3 that sounds like bullshit.

Speaker 2 Yeah. How freeing.

Speaker 3 And then it was a really long, kind of happy stage for me for a long time.

Speaker 2 I just am connecting this to the work.

Speaker 2 I mean, I wonder how you draw the connection, but it does sound like, and tell me if I'm getting this wrong, you are learning to confront these difficult and sometimes very painful ideas head on,

Speaker 2 not to cover them up or push them to the side, to contend with them with more speech, basically, even if it's in your own head.

Speaker 3

Oh, absolutely. Oh, absolutely.

And here's the thing that I just know from being someone who's had a lot of

Speaker 3 mental health struggles over my life too.

Speaker 3 is that the whole don't think about it approach or don't let anybody talk about it approach. It just gives the thing you're trying not to think about more power.

Speaker 3 It makes it bigger and scarier than ever.

Speaker 3 And it's so much better, even though it could be an incredibly painful process, to be clear, to face it. I talk about it from, again, a Buddhist perspective.

Speaker 3 Once you accept life as pain, life becomes less painful.

Speaker 2 The changes Greg was making in his personal life came at an important time for his work, just as he was noticing a profound shift on college campuses.

Speaker 2 This was the mid-2010s, the start of what would become a national reckoning over race in America.

Speaker 2 And during visits he made to college campuses as part of his work, Greg started to document a new culture emerging at universities across the country.

Speaker 2 The way he saw it, students were becoming deeply uncomfortable with the kind of discomfort he thought was so essential for personal growth.

Speaker 2 He wrote about those changes with social psychologist Jonathan Haidt,

Speaker 2 first in the Atlantic and then in a book called The Coddling of the American Mind.

Speaker 3 And I wrote about how

Speaker 3 on campuses, we seem to be trying to tell young people life, in fact, isn't pain.

Speaker 3 And if

Speaker 3 you experience pain, there might be something wrong with you. You might need to do something to intervene to prevent that pain from feeling that pain ever.

Speaker 3 And I was like, that is creating a situation in which you're going to have to dig deeper and deeper and deeper to hide from reality. And you're just going to get more and more scared.

Speaker 2 Right. It does

Speaker 2 bring up the onset of what I think a lot of people think about and call cancel culture.

Speaker 3 Yeah.

Speaker 2 I think a moment that marked for many the beginning of this is the video really that you took on Yale's campus. Can you talk to me about that video and about that moment?

Speaker 2 What led up to that confrontation and what was that confrontation?

Speaker 3 Sure.

Speaker 3 In the fall of 2015, all over the country, there was actually a website set up called The Demands that talked about maybe about 100 campuses where there had been what might be called sort of like social justice, Black Lives Matter style protests demanding the following things from universities.

Speaker 3 And these happened at University of Massachusetts, Amherst, there was a big one there.

Speaker 3 And at Yale, the sort of inciting incident was that a group with the backing of administrators had sent out something talking about, you know, be sensitive in your Halloween costume choices.

Speaker 3 Kind of like someone dressing up as like Pocahontas or something like that could be offensive, or someone dressing up like a Klansman would be like the total nightmare scenario.

Speaker 2 A Yale instructor named Erica Christakis decided to weigh in on this debate and wrote her own letter offering guidance to the students in Silliman House, a residential college she helped oversee.

Speaker 3 And she wrote something that, if you really read it, is a defense of the autonomy of students to navigate. situations like this on their own.

Speaker 3 And it shouldn't be up to the administration to be making these decisions for them.

Speaker 3 And that the right to be transgressive in some way, to sort of push some boundaries and maybe even offend a little bit is something that they should be allowed to do.

Speaker 3 And students will figure out if they're going going to register their offense or not with something that's ultimately up to them. It was an old-fashioned defense of student autonomy.

Speaker 3 And this was treated as if she was saying everybody should dress up like Klan people. So when I was there, this was all blowing up.

Speaker 3 And there had been a bunch of student activists really angrily marched to Silliman College, which is where Erica was one of the heads of the colleges, along with her husband, Nicholas.

Speaker 3 And I'd kind of made friends with the groundskeeper there.

Speaker 3 And he he came over to me and he was like have you seen nicholas i was like yeah i've seen nicholas like the you know like what what are you talking about he's like yeah he's in the courtyard i was like okay he's like yeah and he's surrounded and i was like wait what yeah

Speaker 3 so i i come out

Speaker 3 i'm doing my best everyone i'm doing my best and there's this crowd around

Speaker 3 nicholas i'm just saying are you gonna are you gonna can i let him finish are you going to address the heart of her comment that's and it kind of got this sort of like carnival almost feel to it

Speaker 3 you know like there's people snapping and like people kind of like cracking jokes like around the perimeter and all this kind of stuff this is a whole scene this is a whole scene are you gonna give an apology are you gonna say that you're hearing us

Speaker 3 and it's a really heated argument with student activists demanding that Nicholas apologize for his wife.

Speaker 2 Greg took out his phone and recorded the incident.

Speaker 2 He later published the footage online, something he decided to do because he wanted to protect the Christakises, who were afraid of losing their jobs.

Speaker 3 And what's funny is like the part that really went viral was the thing that got called Treaking Girl.

Speaker 3 It's about creating a home here.

Speaker 3 Which with the student saying he's disgusting, like, why do you even work here? You know, like...

Speaker 3 But sending out that email, that goes against your position as master. Do you understand that?

Speaker 3 No, I don't agree with that.

Speaker 3

Then why the fuck did you accept the position? Why the fuck hired you? I have a different feeling. You should step down.

If that is what you think about being a fan of you should step down.

Speaker 3 And Nicholas, in my opinion, handling this with supreme self-restraint and in a way that showed a lot of thoughtfulness.

Speaker 3 These Frenchmen tell me that they think this is why Gail is?

Speaker 3 Do you hear that? They're going to leave. They're going to transfer because you are a poor student.

Speaker 3

You did not sleep at night. We're out.

We're out. You are disgusting.

Speaker 3 And we were trying really hard to get the school to say we are not going to punish Nicholas and Erica. And it took the school,

Speaker 3 it felt like forever, might have been as little as a week or 10 days before they actually issued a statement, kind of almost under the radar, like sort of like publicly, but not within Yale, that Nicholas and Erica were not going to be punished.

Speaker 3 And we sort of counted that as a victory. But then, as time went on, you know, they got forced out of Sullivan College when I believe they did nothing wrong.

Speaker 3 A lot of people were annoyed that two of the people who were like really leading that effort, you know, got awards from Yale University.

Speaker 2 I mean, the video went viral, and the kind of what was termed shrieking girl, that part in particular, became well known because a lot of people saw what was happening as unfair to Nicholas, right?

Speaker 3 Yeah. Yep.

Speaker 2 Then there was this other reaction, right, from those who would defend the students who said, look, they're just exercising their free speech. Right.

Speaker 2

You know, they're allowed to go and say what they want to these professors. That's part of what the First Amendment protects.

What's your response to that? Or what was your response to that?

Speaker 3 So we generally at FIRE don't comment on the content of the speech that we defend, or at least we try to be very restrained in how much we do that. But we always say, but with one exception.

Speaker 3 If they're calling for people to get fired, if they're calling for people to get censored, we will argue back against that. And we will argue back strongly in many cases.

Speaker 3 So I think that students have been mad at professors all throughout history, but sometimes that might mean a sharp rebuttal in the student newspaper or, you know, even going so far as protesting that person.

Speaker 3 But it is not historically normal for that to be, I'm getting this guy or this woman fired.

Speaker 2

Right. I mean, and in this case, obviously, as you said, Professor Kostakis, he didn't get fired.

You said he got pushed out. He got, he resigned eventually, right? He and Erica.

Speaker 3 From Solomon Hole, yeah. Right.

Speaker 2 What you were doing was saying, look, this professor shouldn't get fired for this

Speaker 2

or punished for this. Yeah.

But there's something else that I think you're getting at and that I've heard you talk about,

Speaker 2 which is,

Speaker 2

sure, the students may have the right to do this. If you want a culture of free speech on campus, it's probably not the right path shouting people down.

Explain that.

Speaker 3 Yeah, I mean,

Speaker 3 I believe very passionately in sort of like the highest functions of higher education. And certainly, of course, you know, one of them is in the name is that they're supposed to educate.

Speaker 3 But really, I think the reason why we give such, you know, special place of honor in American society for higher education, it's the knowledge creation.

Speaker 3 aspect of it, that essentially, like, we are supposed to create this institution to help us see the world as it actually is, because seeing the world as it actually is is surprisingly an arduous, difficult, never-ending process that goes against our intuitions.

Speaker 3 That's not, you know, like always the way we understand it.

Speaker 3 And I think that when it comes to sort of like the attitude that's the best for truth seeking, it is that powerful curiosity to figure out where people are coming from and then the ability to

Speaker 3 sort through that.

Speaker 3 If you're shouting people down, you know, like that's mob censorship. That's basically saying, and because people, people miss this part of it.

Speaker 3 It's like, but the students wanted that person shouted down. And I'm like, okay,

Speaker 3

where to begin on this? One, freedom of speech is anti-democratic. And people are like, what the hell are you talking about? I'm like, no, no, no.

You need to understand this.

Speaker 2 Yeah, what do you mean by that?

Speaker 3 This is what I mean. The freedom of speech of the minority cannot be overruled by the majority.

Speaker 3 So in a pure democracy, it's one of the reasons why the founders were a little bit skeptical of the word democracy itself, because they thought of Athenian democracy, where basically if you had enough votes, you could do whatever you wanted.

Speaker 3 And the Bill of Rights is about saying, no, no, you can't. You are forbidden from letting the majority tell the minority what they cannot say.

Speaker 3 So like it is something where we're saying, listen, democracy goes so far, but you still have these protected individual rights, you know, that cannot be easily voted away.

Speaker 3 I listen to students say things like,

Speaker 3 well, how can I stop these points of view that I think are dangerous or harmful or like whatever?

Speaker 3 And part of the answer is, well,

Speaker 3 to a degree, you you can. And it's good that you can't.

Speaker 3 Because, for example, as I come back to a lot, if it's what someone really thinks, it's worth knowing always.

Speaker 3 But in many cases, the way it works on campus, it's a locally politically unpalatable argument that they're going after.

Speaker 3 That in some cases, they need to understand better or they need to actually hear.

Speaker 3 And watching that sort of like in action at Yale, what Erica was saying was being misconstrued as she's saying that people should be intentionally, racially pissing each other off, as opposed to the more, frankly, interesting argument, which is that, yeah, like allowing student autonomy, it's going to mean that there are going to be abrasions and offenses and transgressiveness and all this kind of stuff.

Speaker 3 But the healthy way to do it is as we're educating people is to learn how people can navigate this within their peers, which is a deeper, more interesting argument.

Speaker 2 After the Yale incident, Greg and his foundation took on a wave of new cases involving free speech issues on college campuses, work that only grew during the Biden administration.

Speaker 2 They also created a ranking of colleges based on the student experience of free speech.

Speaker 2 Some of the most well-known legacy institutions, like Harvard University, ranked lowest on the foundation's list.

Speaker 2 And this work made Gregg and Fire a reviled group among some on the left, who considered Gregg, in particular, a champion of right-wing causes.

Speaker 2 One of the arguments that I know you've heard in the course of your work that people make to defend the institutions that then followed up and did fire these professors during this time is, look, these are like private companies.

Speaker 2

They're allowed to associate with whatever speech they want. If they don't want to be associated with the speech of these professors, that's their right.

What do you make of that?

Speaker 3 Now, public colleges are actually bound by the First Amendment.

Speaker 3 They have to protect the free speech rights of professors and students. When When it comes to private schools, the law is essentially

Speaker 3 and Fire's argument since day one is that you have to live up to your contractual promises of free speech and academic freedom.

Speaker 3 And practically every private school in the country does promise academic freedom and free speech. But I go even further than Fire's position on this.

Speaker 3 I make the point that these institutions have a very hard time.

Speaker 3 functioning if they don't allow for dissent and candor, all of these things that actually make truth-seeking very difficult, you know, not to have.

Speaker 3

So you shouldn't think of this as just any private company, just saying it's like, listen, Jerry said something really dumb. He's a spokesperson.

Jerry's got to go.

Speaker 3 It's like, no, your entire function here is to be able to handle this kind of discussion, this kind of dissent, all this kind of stuff.

Speaker 3 So it's a very different phenomenon when universities are getting rid of professors or students because of things they said, even if they are private.

Speaker 2 Greg, I've heard you say in other contexts something that I really personally identify with as a journalist, which is it does seem as though your love for the First Amendment and for free speech, it comes from this idea that essentially as a human race, we really don't know what we don't know.

Speaker 2 And ensuring that people feel totally free to say whatever is on their mind is a way of ensuring that we are as aware as possible, to the extent possible of all the potential realities out there.

Speaker 2 And yes, sometimes that will be very disruptive. It could be painful personally, politically, whatever it is.

Speaker 2 But the approach it sounds like you advocate is just observing that, being aware of that, and maybe getting closer to truth in that way.

Speaker 3 And I do think of human variability on opinion as being a very important truth.

Speaker 3 And I think about, you know, like the revolution in gay rights in the 70s that Jonathan Rauch, you know, who's also a dear friend, but a big advocate for freedom of speech, would talk about.

Speaker 3 But what you had long before that was a lot of people observing the fact that, yes, prior to the 1970s, people believed that homosexuality was a mental illness.

Speaker 3 But this was conflicting with people's ordinary experience of knowing and loving people who were closeted gay people and being like, well, they're they're wonderful, brilliant, you know, all of these things.

Speaker 3 And it just seems to be like, this is the one thing that's different about them.

Speaker 3 But what if you're not allowed to say that, and even when there's just a high social premium against saying that, you don't actually have that aha experience that we suddenly had in the 1970s.

Speaker 3 First of all, when it was no longer considered to be a mental health issue, and when you actually had people like Frank Kameny using his freedom of speech to point out not just that there are way more gay people in your life than you actually knew, and that this this private knowledge becomes public, but also importantly, and this is only important for people who advocate for hate speech to understand, the fact that people could see how bigoted and pitiable some of the worst anti-gay rights activists were was important to win sympathy over for the cause.

Speaker 3 So I think about the problem of sort of...

Speaker 3 private knowledge that people don't share and how that can really be held back in a situation where candor is not a high value.

Speaker 2 I want to fast forward, you know, from this period to 2024, when you saw the Trump campaign really seize on a lot of the issues that fire was most concerned with and turn it into this campaign issue, the idea of cancel culture, kind of limiting speech.

Speaker 2 You know, what did you make of that when it becomes so central to the Trump campaign's appeal to voters?

Speaker 3 It wasn't a surprise, and we were fully expecting, you know, abuses from the Trump administration. But the scale is even worse than we were expecting.

Speaker 2 We'll be right back.

Speaker 6 This podcast is supported by NRDC, the Natural Resources Defense Council.

Speaker 6 NRDC combines the power of 3 million supporters with 700 staff scientists, lawyers, and advocates to take on the biggest threats facing our planet.

Speaker 6 They've protected endangered species, blocked harmful oil and gas pipelines, and won landmark cases that safeguard clean air and water. Be part of their next victory.

Speaker 6 For daily listeners, donate at nrdc.org/slash daily and your gift will be matched five times.

Speaker 1

We all have moments when we could have done better. Like cutting your own hair.

Yikes. Or forgetting sunscreen so now you look like a tomato.

Ouch. Could have done better.

Speaker 1

Same goes for where you invest. Level up and invest smarter with Schwab.

Get market insights, education, and human help when you need it. Learn more at schwab.com.

Speaker 1

A biotech firm scaled AI responsibly. A retailer reclaimed hours lost to manual work.

An automaker now spots safety issues faster.

Speaker 1 While these organizations are vastly different, what they have in common sets them apart. They all worked with Deloitte to help them integrate AI and drive impact for their businesses.

Speaker 1

Because Deloitte focuses on building what works, not just implementing what's new. The right teams, the right services and solutions.

That is how Deloitte's clients stand out.

Speaker 1 Deloitte together makes progress.

Speaker 2 Walk me through the abuses

Speaker 2 in your words that you have seen so far from the Trump administration. What has stuck out in your mind the most in terms of what Trump has done on free speech thus far?

Speaker 3 Honestly, like the most troubling one to me and the least appreciated are the attacks on the law firms that opposed him.

Speaker 3 They went after law firms that hired people who were involved in investigating the Russia claims, law firms that had lawyers who were involved in the January 6 hearings, like all things that

Speaker 3 these lawyers have every right. to engage in as part of their profession, as part of their societal role.

Speaker 3 And it was incredibly vindictive going after these law firms and saying two things that they couldn't do, they might lose all their security clearance, and two, that they couldn't go into federal buildings, which of course implies that they can't go to court.

Speaker 2 Is this a speech issue?

Speaker 3

Aaron Powell, I think it is, because I run a group that has a litigation arm. And if I can't oppose the government on things, I think it's very much a speech issue.

It's an advocacy issue for sure.

Speaker 3 It's the right to petition the government for address of grievances.

Speaker 3 It's a huge part of the First Amendment.

Speaker 3 We're in court with Trump himself right now.

Speaker 3 We're suing someone who has suggested that he can take away nonprofit status and has gone after every other opponent, as best I can tell, he's ever had in his life.

Speaker 3 So I'm a little bit waiting for, you know, when is it going to be our turn?

Speaker 2 Okay, talk to me about what you've seen and how you interpret Trump's actions with regard to universities.

Speaker 3 There is a lot

Speaker 2 there to unpack. What is kind of stuck in your mind as the most important?

Speaker 3 I would say that the behavior towards Harvard was a lot of the most galling stuff.

Speaker 2 Greg has a running list of the tactics the Trump administration has used to pressure universities.

Speaker 3 They're going to remove federal funding using the title state. You can no longer have foreign students there.

Speaker 3 Then you have the removal of NIH funding.

Speaker 2 And no university has drawn more of the government's attention than Harvard.

Speaker 3 They were utterly showing their cards that this was just another attempt to get Harvard to capitulate.

Speaker 2 And all this, Greg, has has put you at fire in this really unique position of now defending Harvard that you had spent years kind of criticizing and calling out.

Speaker 2 So were you surprised that you ended up in this position? Not really.

Speaker 3 I mean, like, I spend a lot of time defending people who hate my guts, and that's part of the gig. You know, I know that there are people within the institution that really want to reform it.

Speaker 3 They really want to improve it. But no way in hell are they going to capitulate to the government when it's demanding things that go well beyond its powers.

Speaker 2 Aaron Ross Powell,

Speaker 2 so I have a question that is about people on the right who look at what the Trump administration is doing in universities and they say, look, these academic institutions have amassed so much power.

Speaker 2 And, you know, to them,

Speaker 2 these institutions are imbued with left-wing ideology to the point where they are just incapable of change. I'm embodying this argument right now.

Speaker 2 And so if they're incapable of change and we think they should be changed, all we're doing is forcing the issue.

Speaker 3 Yeah.

Speaker 2 What do you say to that?

Speaker 3 I say I believe that there are lots of ways you could actually completely within the law improve and reform higher ed in ways that makes it more rigorous, less expensive, you know, increases competition, that actually allows lots of things that could even make it more egalitarian.

Speaker 3 But you can't just rule from on high and say that the federal government now demands that you have more conservative professors. Like that is not an option.

Speaker 2 The ends don't justify the means, is what you're saying.

Speaker 3

Exactly. There seems to be a core of an idea that you want to defund, to the extent possible, institutions where the left has a lot of power.

So media, so higher ed and big-name law firms.

Speaker 3 Let's take the Jimmy Kimmel case, which we were horrified about but not really surprised about. That was a case where

Speaker 3 if they wanted to get rid of Jimmy Kimmel and they decided to be more canny about it and exercise sort of like pressure behind the scenes, they probably could have pulled it off.

Speaker 3 But instead, you have Trump actually on record like the previous summer saying, Kimmel's next, you know, and then you have Brendan Carr going out there, who used to actually talk a good game on free speech.

Speaker 3 The chairman of the FCC. Of the chairman of the FCC, used to talk a good game on free speech as well, you know, saying we can do this the hard way or the easy way.

Speaker 3 It must be frustrating for some of the White House lawyers to have the people in charge basically say, you know, in the name of unconstitutional viewpoint discrimination, I'm now going to do the following, you know, 15 things.

Speaker 3 And it's like, oh, great. Now we're going to lose in court.

Speaker 2 So, okay, can I ask about that episode of those comments by the FCC chair and then ABC moving to temporarily suspend Kimmel? You've seen a lot over the course of your career. Where does this rank

Speaker 2 for you?

Speaker 3 The funny thing about Kimmel was a lot of people thought that this really seared in their brains, but it wasn't even the worst thing we'd seen from the Trump administration that week, because that was the week after Charlie Kirk was killed.

Speaker 3 The extent to which the Trump administration exploited that once again, just to go after their perceived enemies, was stunning.

Speaker 3 And, you know, suddenly Pam Bondi is arguing, if people say insensitive things about the death of Charlie Kirk, well, that's hate speech and we can go after you.

Speaker 2 Well, I mean, and the Times reported on all these people who lost their jobs for saying

Speaker 2 kind of negative things about Charlie Kirk.

Speaker 3 And we're actually working on a case right now where an ex-cop in Tennessee was put in jail for 37 days for a meme of Trump saying, get over it about one of the school shootings.

Speaker 3 And he was saying like, well, this seems relevant today now that everyone's talking about Charlie Kirk.

Speaker 3 And the claim was that because he sent that in response to Charlie Kirk, that was somehow like a threat, but that doesn't pass the laugh test.

Speaker 3

And I want to be really clear here, 37 days in jail for clearly protected speech. Wow.

I'm hard pressed to think of another example, at least since the 1920s, that's nearly that bad.

Speaker 2

So in the days after that, the assassination of Charlie Kirk, you wrote something in the free press that really stuck out to me. I have it here.

You suggest that

Speaker 2 equating speech with violence, as has happened on many college campuses, you say, you know, paves the way for attacks like this.

Speaker 2 You know, you said in doing that, you, quote, hand extremists a moral permission slip to answer speech with force. So my question is,

Speaker 2 are you suggesting there essentially that cancel culture created the conditions for a murderous attack like this?

Speaker 3 I would say that anytime you have people like literally equating words with violence, you're playing a very very dangerous game and you might not really fully understand how dangerous that is.

Speaker 3 And I'm speaking at Utah Valley University and I do think.

Speaker 3 And I'm scared, to be frank.

Speaker 2 Meaning you're scared of potentially being hurt

Speaker 3 in a way I've never been before in my career.

Speaker 3 You got to recognize that when you're actually using this convenient rhetorical argument that makes you feel very powerful in in certain environments of being like, your words are violence, that it's an insult to those of us who have actually experienced violence.

Speaker 3 And I think that words are tough.

Speaker 3 I mean, I don't love you anymore is the most devastating thing someone could actually say, and that could hurt a lot more than being punched, for example, like over time.

Speaker 3 Particularly when you're talking about this kind of violence, like the life or death stuff, it doesn't, we are so lucky to have freedom of speech as an alternative to resorting to violence.

Speaker 2 Okay, this is something I've been wanting to ask you this whole time.

Speaker 3 Oh, no.

Speaker 2 Given all the examples that you've been citing, given the climate that you've been describing, the genuine fear that you feel right now,

Speaker 3 I have to ask,

Speaker 2 do you think things are worse or better

Speaker 3 now?

Speaker 2 than they were during the Biden era.

Speaker 3

Definitely worse. And I think we are in the crisis.

And I don't think where this is going to be like a normal administration.

Speaker 3 Maybe I'm saying this just at the moment where some additional sanity will prevail, but I doubt it.

Speaker 2 Can you make the case for me that it's worse? I mean, if you're marking

Speaker 2 in time, what feels actually measurably worse right now than what you've seen before, than what we saw during the Biden administration, What is it?

Speaker 3 Aaron Powell, because it's federal power.

Speaker 2 Say more about that.

Speaker 3 I feel like what we saw in 2020 was primarily a cultural problem, but a deep cultural problem. But when you're actually going after law firms, when you're actually

Speaker 3 saying that you're going to dangle whether or not you're able to do a merger if you play ball with the government and give it better coverage, like I'm not familiar with anybody at least saying that in public before.

Speaker 3 And when it comes to higher ed, like even the suggestion that essentially that you would want great federal control over private institutions, that is worse than I saw.

Speaker 3 And again, I thought the cultural problems were serious, but I thought there were many sensible ways you could have helped address them. But yeah, I would say the last eight months have been worse.

Speaker 2 I'm wondering what you would make of the argument that Trump rode into office in no small part by leveraging the very things that you spent a lot of time bringing to the fore, the illiberalism on college campuses.

Speaker 2 And I want to read here from something that a professor who recently left Yale told my colleagues at the times. He said, quote, the moral panic about leftism on universities is largely their fault.

Speaker 3 Referring to fire here.

Speaker 2 What do you make of that accusation? And do you feel any responsibility for laying the groundwork for what we've seen now?

Speaker 3 If I believe that there wasn't a grave problem in higher ed that was very, very real, if I felt like, oh my God, I exaggerated it. I didn't exaggerate it.

Speaker 3 This was a very real thing that people were responding to. And my point has always been, I've been doing this for 25 years.

Speaker 3 If you'd listened to us 15 years ago, there wouldn't have been this kind of excuse just laying at your feet for the Trump administration to pull.

Speaker 3 So like the idea that the person who is warning you and even saying things like, this is going to create a right-wing backlash. And it's created a right-wing backlash.

Speaker 3 And I think people who would rather me not have said anything over the last 25 years are saying that I should apologize for what I said, but I'm not about to do that.

Speaker 3 Yeah.

Speaker 2 You're saying the calling out is a necessary thing for you and for the culture in general.

Speaker 3 Exactly.

Speaker 2 Okay, I want to return to this idea of creating a culture of free speech and to the benefits of creating that kind of culture.

Speaker 2 Because earlier in our conversation, you laid out this dynamic where if you air bad ideas, ideas that people find repugnant, they will get exposed in the public square and eventually many people will turn on them because of that exposure.

Speaker 2 I'm wondering though, if that is always

Speaker 2 true.

Speaker 2 Because what we're seeing right now is this debate that's happening about platforming people with hateful ideas.

Speaker 2 I'm thinking specifically of the conversation around avowed white nationalist Nick Fuentes being invited onto Tucker Carlson's podcast recently. And

Speaker 2 the question that's being asked is, does platforming someone like Fuentes just allow those ideas to reach a broader audience and gain purchase with more people?

Speaker 2 Does it just normalize those ideas rather than chasing them off the public square? Because as far as I can tell, the platforming of someone like Fuentes has only brought him more into the mainstream.

Speaker 2 It hasn't actually hurt his popularity.

Speaker 3 There's this kind of straw man version of the argument for free speech, which is that all you have to do is let speech be as free as possible and everything will work out great.

Speaker 3 We think freedom of speech is a necessary precondition to human rights and for that matter knowing the world as it is. It's necessary, but it's not sufficient to addressing the ills of the world.

Speaker 3 But it is a minimum condition. If we're going to be a democratic society, we can't hate the people so much that we can't trust them to hear things and come to conclusions.

Speaker 3

You know, like that's not a free society anymore. That's a paternalistic or maternalistic society.

Like the goal of the free speech defender is to get us off the seesaw of who gets to censor who.

Speaker 3 Now, what does that mean for platforming? I do actually think that

Speaker 3 hopefully we can have a society where someone can have someone odious on their show, you know, ask them questions, and we don't assume that that those ideas spread like viruses into other people's brains.

Speaker 3 And I think a lot of times we think that just by shutting this person up or by not actually anyone being allowed to hear from them, that's solving the problem.

Speaker 3 But there's group polarization research that essentially, if you just get people to talk to the people they already agree with, they tend to get more radicalized in the direction of the group.

Speaker 3 Whereas if you have people talk to people they disagree with, it works better.

Speaker 2 Even, Greg, in a world where people are really only listening to people they agree with, where these media environments are so siloed, you still think that's the case?

Speaker 3 I think that sometimes in the effort to sort of fix problems with humanity, we think if we can just shut the right people up, these problems are going to go away. And it never, ever works.

Speaker 2 Jr.: You know, after talking to you, it seems pretty clear that the value of free speech is something that both sides, the right and the left, claim.

Speaker 2 And then you have seen over the course of your career that they also don't always practice what they preach.

Speaker 2 And

Speaker 2 you've given us this defense of free speech that is actually, for me, it's been uniquely personal.

Speaker 2 You've couched it as something that is really important to one's personal mental health and also therefore important to a society's general health.

Speaker 2 And I wonder if that's part of the argument that you would make about why it's essential to democracy. Yeah.

Speaker 3 Or what

Speaker 2 you would say about why it is so worth preserving.

Speaker 3

Yeah, I mean, you're not a free people if you don't have free speech. Like, it's as simple as that.

And people who are in favor of censorship, they really are telling you, don't be yourself.

Speaker 3 They're really saying, don't be authentic, lie if you need to betray what you actually believe.

Speaker 3 And even if they think they're doing it for the absolute best reasons in the world, and usually they do, in most of human history, the censors, they think they're on the side of goodness and right.

Speaker 3 And sometimes I can understand why they would think that.

Speaker 3 But ultimately, so many times when you're looking at threats to freedom of speech, they are about be less of you, be less of who you are, be less authentic.

Speaker 3 And if there's weird things going on in your head, don't tell anyone for God's sakes.

Speaker 3 So I do think that there's that aspect of autonomy that's represented in free speech, I think, is deeply personal to all of us.

Speaker 3 But then there's the informational part of it, just the knowing the world actually as it is.

Speaker 3 Because you simply cannot know what your society looks like if everybody's afraid to say what they really think.

Speaker 2 Well, Greg, thank you so much for your time. It has truly been fascinating to talk to you.

Speaker 3 Thank you. I really enjoyed it, too.

Speaker 3 We'll be right back.

Speaker 1 This podcast is supported by the International Rescue Committee. Co-founded with help from Albert Einstein, the IRC has been providing humanitarian aid for more than 90 years.

Speaker 1 The IRC helps refugees whose lives are disrupted by conflict and disaster, supporting recovery efforts in places like Gaza and Ukraine, and responding within 72 hours of crisis.

Speaker 1

Donate today by visiting rescue.org/slash rebuild. We all have moments when we could have done better.

Like cutting your own hair. Yikes.

Or forgetting sunscreen so now you look like a tomato. Ouch.

Speaker 1

Could have done better. Same goes for where you invest.

Level up and invest smarter with Schwab. Get market insights, education, and human help when you need it.

Learn more at schwab.com.

Speaker 1

Support for this podcast comes from GoodRX. The holidays are here, but so is cold and flu season.

Find relief for less with GoodRX.

Speaker 1

You could save an average of $53 on flu treatments. Plus save on cold medications, decongestants, and more.

Easily compare prescription prices and find discounts up to 80%.

Speaker 1 GoodRX is not insurance, but works with or without it and could beat your copay price. Save on cold and flu prescriptions this holiday season at goodrx.com/slash the daily.

Speaker 2 Here's what else you need to know today.

Speaker 2 During a classified briefing on Thursday, members of Congress watched a video of the controversial airstrike that killed two alleged drug smugglers who clung to a boat in the Caribbean.

Speaker 2 That airstrike in September, a follow-up to an initial attack on the boat, is now the subject of an inquiry by the Senate and House Armed Services Committee.

Speaker 2 But after viewing the video, Democrats and Republicans had starkly different impressions of what had happened and whether it violated the rules of war.

Speaker 3 What I saw in that room was one of the most troubling things I've seen in my time in public service.

Speaker 3 You have two individuals in clear distress without any means of locomotion with a destroyed vessel who were killed by the United States.

Speaker 2 Democratic Representative Jim Himes of Connecticut suggested the video showed the military killing shipwrecked sailors who posed no threat.

Speaker 2 But after watching the same video, Republican Senator Tom Cotton of Arkansas said it appeared to be a lawful attack.

Speaker 3 I saw two survivors trying to flip a boat loaded with drugs down the United States back over so they could stay in the fight and potentially give them all the context we wanted.

Speaker 2 Meanwhile, the New York Times has sued the Pentagon for infringing on the First Amendment rights of journalists by imposing a new set of restrictions on reporting about the military.

Speaker 2 Those restrictions, which cover a wide range of journalistic activities, are contained in a 21-page form form that the Defense Department has required reporters to sign in order to keep their Pentagon press passes.

Speaker 2 Many news organizations, including the Times, have refused to sign the form.

Speaker 2 Today's episode was produced by Astha Chaturvedi. It was edited by Michael Benoit with research help by Susan Lee.

Speaker 2 contains music by Dan Powell, Pat McCusker, Alyssa Moxley, Marion Lozano, and Diane Wong, and was engineered by Alyssa Moxley.

Speaker 2

That's it for the daily. I'm Natalie Kitroev.

See you on Monday.

Speaker 1 This podcast is supported by the International Rescue Committee. Co-founded with help from Albert Einstein, the IRC has been providing humanitarian aid for more than 90 years.

Speaker 1 The IRC helps refugees whose lives are disrupted by conflict and disaster, supporting recovery efforts in places like Gaza and Ukraine, and responding within 72 hours of crisis.

Speaker 1 Donate today by visiting rescue.org/slash rebuild.